Abstract

Background

An increase in lifespan in our society is a double-edged sword that entails a growing number of patients with neurocognitive disorders, Alzheimer’s disease being the most prevalent. Advances in medical imaging and computational power enable new methods for the early detection of neurocognitive disorders with the goal of preventing or reducing cognitive decline. Computer-aided image analysis and early detection of changes in cognition is a promising approach for patients with mild cognitive impairment, sometimes a prodromal stage of Alzheimer’s disease dementia.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review following PRISMA guidelines of studies where machine learning was applied to neuroimaging data in order to predict whether patients with mild cognitive impairment might develop Alzheimer’s disease dementia or remain stable. After removing duplicates, we screened 452 studies and selected 116 for qualitative analysis.

Results

Most studies used magnetic resonance image (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) data but also magnetoencephalography. The datasets were mainly extracted from the Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative (ADNI) database with some exceptions. Regarding the algorithms used, the most common was support vector machine with a mean accuracy of 75.4%, but convolutional neural networks achieved a higher mean accuracy of 78.5%. Studies combining MRI and PET achieved overall better classification accuracy than studies that only used one neuroimaging technique. In general, the more complex models such as those based on deep learning, combined with multimodal and multidimensional data (neuroimaging, clinical, cognitive, genetic, and behavioral) achieved the best performance.

Conclusions

Although the performance of the different methods still has room for improvement, the results are promising and this methodology has a great potential as a support tool for clinicians and healthcare professionals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The increase in lifespan experienced in Western societies has largely been driven by medical and technological advances [1]; however, this improvement has resulted in an increasing number of people diagnosed with neurocognitive disorders. In 2010, dementia was associated with $604 billion of healthcare expenses in the USA [2]. Every year, ten million new cases of dementia are registered, and by 2050, it is estimated that 135 million people will have some degree of dementia [3]. Age is the main risk factor for dementia; the prevalence is 1–2% at the age of 65 but reaches 30% at the age of 85. From all neurodegenerative disorders, about 60–90% are characterized as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia subtype (depending on the diagnostic criteria used) [4], for which there is yet no cure.

Patients are typically diagnosed with AD when the symptoms of a cognitive decline have already manifested, i.e., when dementia has appeared. In such cases, the diagnosis is determined too late, failing to implement preventive protocols to reduce cognitive decline. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments have proven to be effective in reducing cognitive and behavioral symptoms in the early stages of the disease [5]. In light of these treatments, recent studies have focused on detecting patients with cognitive impairment that have not reached dementia in order to delay or prevent its development. The last edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) includes a specific category for this type of patients called a mild neurocognitive disorder, analogous to the mild cognitive impairment (MCI) whose main characteristic is having minor memory impairment [4] (throughout this review, MCI will be used instead of mild neurocognitive disorder as it is more frequent in the scientific literature). MCI can, in some cases, be a prodromal stage of dementia, especially for AD [6]. It is worth mentioning at this point that AD should be considered as a continuum, where patients with MCI that will eventually progress to AD dementia already have AD, but the cognitive symptoms have not yet fully manifested. For this reason, it is important to differentiate between those MCI patients that will progress to AD dementia and those who will remain stable.

In late stages, when dementia symptoms have already appeared, AD is easier to confirm with neuroimaging techniques and cerebrospinal fluid evaluations for the presence of neurofibrillary clews, beta-amyloid and tau proteins [7], and temporal cortex atrophy [4]. Nevertheless, in the early stages, although biomarkers may be present in magnetic resonance image (MRI) and/or positron emission tomography (PET) results, the detection of MCI to AD dementia progression remains challenging in the clinical practice [8, 9]. To overcome this challenge, the scientific community now has access to thousands of neuroimaging longitudinal datasets from healthy, MCI, and AD subjects along with other variables (i.e., demographic, genetic, and cognitive measurements, etc.) stored in public databases such as the Alzheimer disease neuroimaging initiative (ADNI) (http://adni.loni.usc.edu). These datasets can be compared and analyzed to perform classification and automatic detection of AD and MCI progression [10, 11] using newly developed computer-aided techniques like machine learning (ML) algorithms. Then, these new tools could be transferred to the clinic to assist in the early diagnosis and prognosis.

The ML paradigm consists of training an algorithm with a dataset; in this case, neuroimaging results together with other clinical variables, to extract common factors that help classify subjects according to a variable of interest. In the case of an early diagnosis of AD and distinction from a stable MCI condition, for example, the algorithm learns to classify the data according to the specific diagnosis and extracts which factors have been the most relevant for the differentiation between the groups. Subsequently, the trained algorithm can be used to classify a specific individual for which we do not know the diagnosis and thus manage to assist in the therapeutic approach [12,13,14]. This technique can be applied to any disease that occurs with morphological changes or with characteristic neural patterns. See Arbabshirani, Plis, Sui, & Calhoun [15] for a review of the same objective and methodology but applied to autism, attention deficit disorder, and schizophrenia.

Recent work has demonstrated that ML algorithms are able to classify images from AD, MCI, and healthy participants with very high accuracy levels [16, 17]. Although such classification has provided valuable information about AD biomarkers, for this technology to have a more substantial clinical impact by empowering a clinician to administer a customized treatment protocol, it is necessary to determine and predict whether a MCI patient will progress to AD dementia or remain stable. The goal of this systematic review is to analyze the existing classification methods based in ML algorithms applied to neuroimaging data in combination with other variables for predicting MCI to AD dementia progression.

Methods

To perform this systematic review, we followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [18, 19]. A systematic search was done to find studies that included ML methods to predict MCI to AD dementia progression using neuroimaging techniques. Progression to AD dementia from MCI is established when, during a follow-up period (3 years for ADNI and 1 year for AddNeuroMed databases), a patient that was initially classified as MCI, is diagnosed with Alzheimer (that is a “progressive MCI” or pMCI) based on clinical criteria (MMSE and CDR scales, and NINCDS/ADRDA criteria for probable AD dementia [20, 21]). Patients are considered “stable MCI” (sMCI), when they were diagnosed as MCI at baseline and the diagnosis remained as MCI during the follow-up.

Only articles written in English and published between January 2010 and May 2021 (included) were selected. Articles published before 2010 were not included because the technological (e.g., computational power, graphical processing units) and methodological (e.g., ML and deep learning algorithm development) gap between those studies and the current standards make them hardly comparable. In fact, even the comparison between articles published in the early vs. the late 2010s presents methodological gaps. These differences are not only due to better methods but mainly to technological advances that were not possible before and early 2010s, and the growth of the ADNI database.

We performed an advanced search concatenating terms with Boolean operators in PubMed, PsycINFO, and Web of Science databases as follows: (“computational neuroscience” OR “artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “neural network*”) AND (“neuroimag*”) AND (“Alzheimer*” OR “AD dementia”) AND (“mild cognitive impairment” OR “MCI”) AND (“conversion” OR “predict*” OR “follow-up”).

After removing duplicates, the eligibility criteria were applied by two independent reviewers (SG and RVS) to select only the articles that included (1) prediction of MCI to AD dementia conversion, (2) use of neuroimaging data, (3) classification methods based on ML algorithms, and (4) accuracy results.

Once the selection of studies was concluded, the following data was extracted for each study: (1) first author and year of publication, (2) groups, (3) sample size and mean age, (4) database, (5) neuroimaging technique used and variables selected, (6) classification method, (7) validation method, (8) accuracy achieved, and (9) area under the ROC curve.

We also analyzed the risk of bias of the selected studies. The aspects considered in the analysis of bias were based on the Cochrane guidelines for systematic reviews [22], but the exact criteria were adapted by taking into account the particular methodology and goals of the studies, focused on creating and validating a classification model in large datasets. The criteria used are detailed in Table 1.

We also performed an interpretability analysis based on the framework proposed by Kohoutová et al. [23]. These authors have developed three levels of assessment for the interpretability of ML models in neuroimaging based on the model itself, the feature selection and characteristics, and biological factors; also, each level has several sublevels. Model-level assessment consists of evaluating the model as a whole and testing it in different contexts and conditions. The sublevels include sensitivity and specificity, generalizability, behavioral analysis, representational analysis, and analysis of confounds. Feature-level assessment consists of evaluating the significance of individual features used in prediction, including stability, feature importance, and visualization. Finally, the biology-level assessment is a validation of the model based on its neurobiological plausibility and it has two sublevels: literature (relationship of the model with previous literature) and invasive studies (the possibility of using more invasive methods).

We assessed whether the studies included in the review complied with each of the sublevels, but we did not include behavioral analysis, representational analysis, and invasive studies sub-levels. Behavior analysis sub-level was not considered because the only “behavior” of the model is to classify subjects, and the behavior is measured as accuracy, which is included in the sensitivity and specificity sublevels. Representational analysis compares the model with other models, other brain regions, or other experimental settings; in our review, the main goal of almost all studies was to find neural patterns that predict AD dementia, and therefore, it is common to use the whole brain as a feature. Also, there is only one experimental setting aimed to find maximum classification accuracy so it cannot be compared to similar experiments in the same study, only with similar literature (which represents another sub-level). Finally, the invasive studies sub-level is not applicable because the long-term objective of these investigations is to find a non-invasive method of predicting AD dementia as soon as possible.

Results

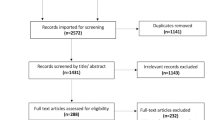

As shown in Fig. 1, the workflow followed for the article selection included the four phases (identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion) proposed by the PRISMA guidelines [18, 19]. The 452 articles remaining after eliminating duplicates were screened, and after applying the exclusion criteria, 117 articles were selected for the review.

PRISMA workflow for study selection adapted from Moher et al. [18]. WOS Web Of Science, AD Alzheimer’s disease, MCI mild cognitive impairment

The risk of bias analysis is shown in Fig. 2 and Table 2. The overall risk of bias of all the studies was considered low. From the 117 articles selected at the eligibility stage, only one study [65] was not included in the qualitative analysis because of the high risk of bias. The sample size in this study was seven subjects, and it did not include any validation method. Therefore, the final number of studies included in the qualitative analysis was 116.

The studies selected for the qualitative analysis are presented in Table 3 following the structure explained in the data extraction section (study, cohort, sample [mean age], database, features and neuroimaging technique, classification method, validation method, results [% accuracy], and AUC ROC).

MRI was the most common kind of neuroimaging used (in 76 out of 116 studies), followed by PET (11 studies), 26 studies included data from both techniques (MRI and PET), two studies used magnetoencephalography (MEG) data, and one study used MRI and MEG data.

Regarding the source of the datasets, 107 out of 116 studies used the ADNI database in any of its versions (ADNI-1, 2, 3, or GO) to obtain samples of healthy, MCI, and AD subjects. Of the remaining eight studies, three used data from AddNeuroMed (https://consortiapedia.fastercures.org/consortia/anm/) database, one used the Australian Imaging, Biomarker & Lifestyle Flagship Study of Ageing (AIBL) database, and four collected their own data. Li et al. [108] used both ADNI and AIBL.

Although almost all studies used the same database, the cohorts selected varied across them. Most articles (66 out of 116 studies) divided their participants into four groups: healthy controls, stable MCI patients (sMCI), progressive MCI patients (pMCI), and AD patients. 21 articles selected three cohorts of MCI, AD, and healthy subjects, although in order to predict the progression to AD dementia, they had to distinguish between pMCI and sMCI patients. The remaining 29 studies used different groups of participants: 21 only sMCI and pMCI, six had healthy controls, and MCI with two of them separating sMCI and pMCI. Wee et al. [113] differentiated between early and late MCI, and Li et al. [106] did not specify the cohorts selected.

The sample size also varied across studies. Wee et al. [37] has the smallest sample with 27 subjects, and Bae et al. [130] has the largest sample with 3940 subjects; the mean sample size was 546 participants. The sample size follows an ascendant trend across years, which may be attributed to the increased data availability in the ADNI database. The mean age ranged from 56 to 79 years old. Although 30 studies did not include the mean age of the sample, they used an ADNI database, and therefore, the age range might be similar to the rest of the studies. The variations in age between studies may be due to differences in participant selection and the moment when the study was conducted (since the ADNI database has been incorporating more data over the years).

As for feature selection, the most common were whole-brain volumes, selected in 70 articles, and intensity measurements of glucose metabolism, selected in 31 PET studies, also 16 studies included genetic features (APOE4 genotype). Other selected features were neuropsychological test results (18 out of 116 studies) and demographic variables such as age (15 out of 116 studies). 42 studies only used one type of features such as 3D MRI data or whole-brain gray matter volumes, and 74 studies selected two or more different types of features. As for the algorithm results, the most useful areas to discriminate between AD patients and healthy subjects or sMCI, were mainly located in the temporal, parietal, and frontal lobes. In particular, the most relevant regions were the hippocampus, amygdala, entorhinal cortex, precuneus, cingulate gyrus, and rostral and caudal areas of the medial frontal lobe.

Regarding the ML methods used to classify the patients and detect probable MCI to AD dementia progression, the most popular were those based on support vector machine (SVM). SVM was used in 60 out of the 116 studies; this method is a supervised ML algorithm that has demonstrated its utility in neuroimaging-based applications, especially in the classification of future clinical outcomes [139]. SVM takes every measurement from every subject as a single point in a multidimensional space, with the number of dimensions being the total number of features of that particular dataset (for example, 93 gray matter volumes from regions of interest). The algorithm then finds the maximal margin separating hyperplane that optimally differentiates groups of data points representing different classes (e.g., pMCI vs. sMCI, or AD vs. HC). The data instances closest to the group boundaries are the support vectors and are, by definition, the ones that determine the position of the hyperplane. The mapping into a higher dimensional space is done by a kernel function, usually polynomial or Gaussian [26]. The SVM algorithm is trained with labeled data (indicating whether the data belongs to a healthy person, sMCI, pMCI, or AD dementia patient, for example) to generate this multidimensional space. Once the model has been trained, we can introduce a new subject with MCI and it will be classified in the multidimensional space into the boundaries of one of the previously defined groups (i.e., sMCI, AD dementia). For example, if the new MCI patient is classified as belonging to the AD or pMCI group, we can infer that this subject is more likely to develop a future AD dementia due to being more similar to subjects in that group. The different groups for classification will depend on the specific methodology of each study.

The combination of SVM with other methods allows to improve feature selection and to avoid overfitting of data, and this will facilitate the generalization of the model (i.e., achieving high accuracy when applied to different datasets). For example, Thung et al. [71] used SVM with multiple kernels (linear, Gaussian, and polynomial) after feature selection with least squares and logistic elastic net regressions and also matrix completion with label-guided low-rank matrix completion method. On the other hand, Toussaint et al. [36] used non-linear SVM with Gaussian Radial Basis Function kernel but only after a two-sample t test and a spatial independent component analysis, performed for the detection of glucose metabolism and characteristic region patterns of AD patients. Other classification methods used were random forest or neural networks that can have different architectures, but the most commonly used for image classification tasks where convolutional neural networks, applied in 16 studies.

As for validation methods, cross-validation was selected in 72 studies, with different numbers of folds and/or iterations. Cross-validation consists in dividing the sample into two sets, one to train the algorithm (training set) and another one for validation (testing set). This partition can be done several times by changing the train/test split of the data, and the accuracy of each iteration can be averaged to obtain a more robust quantification of the model performance instead of just validating the model on one test sample. Another validation method is the leave-one-out cross-validation, selected in 13 studies. In this case, the model is trained with all the data except for one data point, then it tries to classify the data point left out and does the same with the rest of the sample in subsequent iterations. The train/test method was selected in 27 studies with different percentages of data partitions. Finally, three studies validated the model on an independent test set and Ardekani et al. [64] used “out of bag” as a validation method.

The results of ML classification algorithms can be assessed based on their sensitivity (percentage of correctly detected pMCI patients or true positive ratio) and specificity (percentage of healthy or sMCI subjects correctly identified or true negative ratio), or accuracy (percentage of correctly classified subjects). By changing the decision threshold of the classifier, we can compensate the ratio between true positive/true negative and generate a graphic representation of that ratio, or what is known as the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve [140]. The calculation of the area under the ROC curve (AUC ROC) represents a good quantitative index to compare the classification models, since it indicates the ability of the model to predict both the presence and non-presence of disease, or in this case, the progression or lack of progression from MCI to AD dementia [141]. An AUC ROC of one implies a perfect classification of every subject in the sample. The maximum accuracies achieved by every study in the prediction of AD dementia progression from MCI patients or the accuracy of the method in discriminating between a progressive/stable MCI are shown in the “Results” column of Table 3; the AUC coefficient is presented when available.

The mean accuracy of studies that used MRI as neuroimaging technique was 74.5% and 76.9% for studies that selected PET scans. The combination of both techniques achieved even better results with a mean accuracy of 77.5%. AUC ROC results follow a similar pattern with a mean AUC of 0.79, 0.80, and 0.80 for MRI, PET, and MRI+PET, respectively. López et al. [69] used MRI and MEG and achieved an accuracy of 100 and an AUC of 0.97 but with a sample of 33 subjects and finally Pusil et al. [110] (with 54 subjects) and Xu et al. [126] (with 129 subjects) used MEG with accuracies of 100% and 87%, respectively.

Considering the two most popular classification methods (SVM and CNN), the mean accuracies were 75.4% for SVM and 78.5% for CNN. The best results with the SVM algorithm were obtained again by Pusil et al. [110] with 100% accuracy, but using a small sample of 54 that makes the model hardly generalizable. In studies with bigger samples, Guerrero et al. [49] had the highest accuracy results (97.2% with 511 subjects) followed by Lin et al. [122] (97.3% with 164 subjects). Finally, although 43 studies did not report AUC ROC values, the highest reported was 0.98 in Lin et al. [122] followed by 0.98 in Hojjati et al. [85] with 80 subjects. The lowest accuracy reported was found in the study by Plant et al. [24] (50%), who included a small sample size [63] and is the oldest study of all the analyzed, making the comparison between studies difficult. The second-lowest accuracy was achieved by Sorensen et al. [93] (55% with 400 subjects); in this case, the study was part of a data science competition (Kaggle) where data was already preprocessed for all participants and could not be manipulated by the authors. The lowest AUC ROC reported was found in Liu et al. [45] (0.53 and 414 subjects) using SVM and in Pan et al. [123] (0.59 with 787 subjects) with CNN.

Finally, the interpretability analysis is shown in Table 4. Most of the studies presented results of specificity and sensitivity (113 out of 116), about half of them (60 out of 116) made an analysis of confounds, but only Lebedev et al. [50], Li et al. [106], and Syaifullah et al. [135] complied with the generalizability sublevel, testing their model in different datasets. All of the studies performed a stability measurement of their model, and only 25 did not specify which features were the most important for the classification task. On the other hand, less than half of the studies (51 out of 116) presented their results along with some kind of visualization of the most relevant brain areas for the prediction of MCI conversion. Finally, the comparison of the results with the existing literature was done in all of the studies except for four of them.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we analyzed 116 studies, conducted over the last 10 years, which used neuroimaging data to predict conversion to AD dementia from MCI using ML algorithms. The complexity of neuroimaging results and the amplitude of the deterioration and symptoms present in multiple areas and functions in AD, make its detection very complex in patients with MCI by simply visualizing a single patient neuroimaging data. Nevertheless, using the publicly available data collected over the last decades, together with the newly developed ML algorithms, researchers can not only distinguish the brains of AD patients and healthy people with high accuracy, but also predict MCI patient’s disease progression (i.e., whether a MCI patient will progress to AD dementia or remain stable in the future). This information is highly valuable for clinicians in order to achieve a more accurate prognosis and therefore set treatment plans that can slow down the development of the disease and prevent higher degrees of cognitive impairment.

The 116 studies analyzed reached different levels of accuracy using classification methods based on ML algorithms. Only 24 studies focused exclusively on predicting MCI progression, most studies also tried to find the main differences between healthy controls and AD patients. The specific search for AD biomarkers is much more abundant in the literature than predicting progression from a MCI or even from healthy subjects [142]. In any case, in the studies that carried out both tasks and in studies that focused on the prediction of AD progression, the distinction between controls and AD was always more accurate than the distinction between pMCI vs. sMCI, showing the difficulty of finding biomarkers before functional impairment/dementia appear.

One of the main challenges of this review was to compare studies with highly variable methodologies including different samples, preprocessing techniques, types of neuroimaging data, and also different classification and validation methods. Still, studies that achieved higher levels of accuracy have in common the use of multimodal and multidimensional data combined with increasingly complex classification methods. Easy-to-implement algorithms, such as those based on SVM, are leaving room for more complex algorithms based on deep learning paradigms such as neural networks, capable of identifying dementia-associated subtle changes of brain morphology in a way able to increase the number of correctly classified subjects. All methods seemed to benefit from the inclusion of demographic variables and cognitive measurements, and even genetic variables if these were available. Nevertheless, in order for these techniques to be able to help clinicians in their everyday practice, a balance is needed between the most advanced data and algorithms that achieve the higher performance, and the data and methods that might be available in the clinical practice. In this sense, future studies might need to focus more on achieving high performance using large datasets with more essential (and easily obtainable) data such as structural MRI, demographic, and cognitive results.

Regarding the sample, most studies use the publicly available data from the ADNI database. This database is still incorporating new data and the most recent studies even use ADNI-2 and ADNI-3 [113, 117]. The main problem of the studies performed 10 years ago is their smaller sample size. Furthermore, even if two studies report similar accuracies, a study with a bigger sample size will have results that are more generalizable. For example, Plant et al. [24] and Popuri et al. [92] obtained similar accuracies of 75% and 79% of correct classifications, respectively, but Popuri et al. [92] used a sample of about 30 times larger. Upon review of the recent developments in the field, it is apparent that as these patient populations continue to age and their disease progression matures and is clinically diagnosed, the inclusion of their ongoing neuroimaging data will enrich these public databases, thereby enabling improved validation of classification methods. Nevertheless, it should be noted that a follow-up of 2 or 3 years might not be long enough to detect progression to AD dementia. Therefore, subjects considered as stable MCI or even as healthy subjects might, in fact, progress to AD dementia in the long term. This problem will always be present with the inclusion of new cases in the ADNI database, but the follow-ups recorded will be increasingly long-lasting, thus being more useful. On the other hand, in order for these methods to be clinically useful, the models have to be tested, not only in big samples, but also in more variable and diverse groups of people, other than the ADNI sample. This approach is highlighted by Lebedev et al. [50], for example, who applied the model to the ADNI and then to the AddNeuroMed cohort, achieving similar performance and accuracy results in both, making it more robust for future clinical implementation.

Another interesting result from the inclusion of neuroimaging data in ML algorithms is the possibility of finding out which brain regions are more relevant to predict the conversion from MCI to AD dementia. In this case, the highlighted regions as informed by the algorithms (hippocampus, amygdala, entorhinal cortex, precuneus, cingulate gyrus, and medial frontal lobe) have been widely validated by the scientific literature as relevant in the progression to AD [8, 33, 34, 143,144,145,146,147]. This coincidence between the literature and the algorithm results supports the notion that the classification methods can detect differences between groups based on relevant neuroimaging features.

In terms of accuracy, although the algorithms are useful and able to discriminate the brain characteristics of AD, the performance of the algorithms are far from being specific enough to leave complete diagnosis in the hands of automated methods, so the judgment of a clinical professional will remain crucial in the near future. Also, clinical criteria can achieve sometimes similar results in terms of predicting the conversion from MCI to AD dementia 1 year before its onset [148]. Nevertheless, computer-aided diagnosis, when implemented in the clinical practice, will offer a faster, easier to perform, and earlier detection way of predicting the potential progression to AD dementia in MCI patients. Therefore, the automated methods discussed above present a low-cost approach that can be useful as a first approximation, a method to discriminate ambiguous cases, and a support tool for large datasets.

Clinical research is moving towards a broader and more open context where professionals from very different disciplines might be interested in these types of studies. As such, it is important to present the results from complex neuroimaging classification studies as clearly as possible. The framework to interpret ML models provided by Kohoutová et al. [23] is a helpful starting point for this purpose. Most or all of the studies reviewed here included information about the specificity and sensitivity (model level), the stability of the models, and the most important features selected (feature level), along with a comparison with the previous literature (biology level). However, there are some important issues that should be addressed in future studies such as the inclusion of visualizations of the most relevant brain areas to predict MCI conversion, an adequate analysis of confounds, and generalization methods. These specific improvements would provide more comprehensive and comparable studies.

Limitations

Regarding the limitations of the review, it is worth mentioning that we did not include methodological details such as the preprocessing methods to obtain the neuroimaging results or the mathematical development of the algorithms. This information could have provided a better understanding of each model's performance and how the data is classified to differentiate between groups, but these deep methodological analyses were out of the scope of this review given its more clinically oriented focus.

Conclusions

The recent trend in research to find diagnostic automation methods presents great potential in the early detection of neurodegenerative diseases. Since structural changes appear before the clinical symptoms manifest, there is a valuable period of time in which the morphological and functional changes in the brain can be detected and, therefore, used to predict and provide clinical treatment to slow down the future development of a neurological disease.

Research in this field is still rapidly advancing, new increasingly complex algorithms continue to be developed, and access to higher levels of computational capacity is also increasing, as well as the precision and resolution of neuroimaging techniques. In the future, we can expect faster, more precise, and more efficient classification methods that may be directly incorporated into the neuroimaging techniques themselves that enable the generation of a diagnostic hypothesis with a simple scan of a patient’s brain. However, the challenge to translate this knowledge into daily practice remains. This challenge will be overcome on the one hand by increasing the generalizability of the classification methods as they are applied to more diverse samples and, on the other hand, by finding the trade-off between the higher precision achieved when including complex information and a sufficient performance using only the clinical data commonly available for the clinicians. Thus, future studies should focus on obtaining good results using data easily available in the clinical practice (structural MRI, demographic data, and cognitive results, for example) and making their models as much generalizable as possible using more diverse and inclusive samples.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADNI:

-

Alzheimer’s disease neuroimage initiative

- HC:

-

Healthy controls

- MCI:

-

Mild cognitive impairment

- ML:

-

Machine learning

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance image

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- pMCI:

-

Progressive mild cognitive impairment

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- sMCI:

-

Stable mild cognitive impairment

- SVM:

-

Support vector machine

References

Menéndez G. La revolución de la longevidad:cambio tecnológico, envejecimiento poblacional y transformación cultural. Rev Ciencias Soc [Internet]. 2017;30(41):159–78. [cited 2021 Feb 9]. Available from: http://www.scielo.edu.uy/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0797-55382017000200159&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es.

Prince MJ, Wimo A, Guerchet MM, Ali GC, Wu Y-T, Prina M. World Alzheimer Report 2015 - The Global Impact of Dementia: An analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. London: Alzheimer's Disease International; 2015. p. 84.

Dementia [Internet]. [cited 2021 Feb 9]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/dementia#tab=tab_1. Accessed 9 Feb 2021.

APA. American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, American Journal of Psychiatry. 5th ed; 2013.

Robinson L, Tang E, Taylor J-P. Dementia: timely diagnosis and early intervention. BMJ. 2015;350(jun15 14):h3029 [cited 2019 Dec 21] Available from: http://www.bmj.com/cgi/doi/10.1136/bmj.h3029.

Gauthier S, Reisberg B, Zaudig M, Petersen RC, Ritchie K, Broich K, et al. Mild cognitive impairment. Lancet. 2006;367(9518):1262–70.

Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82(4):239–59.

Hinrichs C, Singh V, Xu G, Johnson SC. Predictive markers for AD in a multi-modality framework: an analysis of MCI progression in the ADNI population. Neuroimage. 2011;55(2):574–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.081.

Zhang D, Shen D. Multi-modal multi-task learning for joint prediction of multiple regression and classification variables in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2012;59(2):895–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.069.

Pellegrini E, Ballerini L, del C Valdes Hernandez M, Chappell FM, González-Castro V, Anblagan D, et al. Machine learning of neuroimaging for assisted diagnosis of cognitive impairment and dementia: a systematic review. Alzheimers Dement Diagnosis, Assess Dis Monit. 2018;10:519–35.

Samper-González J, Burgos N, Fontanella S, Bertin H, Habert MO, Durrleman S, et al. Yet another ADNI machine learning paper? Paving the way towards fully-reproducible research on classification of Alzheimer’s disease. In: Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); 2017.

Davatzikos C, Fan Y, Wu X, Shen D, Resnick SM. Detection of prodromal Alzheimer’s disease via pattern classification of magnetic resonance imaging. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29(4):514–23.

Klöppel S, Chu C, Tan GC, Draganski B, Johnson H, Paulsen JS, et al. Automatic detection of preclinical neurodegeneration: Presymptomatic Huntington disease. Neurology. 2009;72(5):426–31. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000341768.28646.b6.

Lao Z, Shen D, Xue Z, Karacali B, Resnick SM, Davatzikos C. Morphological classification of brains via high-dimensional shape transformations and machine learning methods. Neuroimage. 2004;21(1):46–57.

Arbabshirani MR, Plis S, Sui J, Calhoun VD. Single subject prediction of brain disorders in neuroimaging: promises and pitfalls. Neuroimage. 2017;145(Pt B):137–65 [cited 2021 Feb 9] Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC5031516/.

Jo T, Nho K, Saykin AJ. Deep learning in Alzheimer’s disease: diagnostic classification and prognostic prediction using neuroimaging data. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11 [cited 2021 Jan 25] Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31481890/.

Sarica A, Cerasa A, Quattrone A. Random forest algorithm for the classification of neuroimaging data in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:1–12.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–12.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, John PA. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration; 2009.

McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011;7(3):263–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005.

Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, DeKosky ST, Barberger-Gateau P, Cummings J, et al. Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(8):734–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70178-3.

Higgins JPTGS. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 . The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011.

Kohoutová L, Heo J, Cha S, Lee S, Moon T, Wager TD, et al. Toward a unified framework for interpreting machine-learning models in neuroimaging. Nat Protoc. 2020;15(4):1399–435.

Plant C, Teipel SJ, Oswald A, Böhm C, Meindl T, Mourao-Miranda J, et al. Automated detection of brain atrophy patterns based on MRI for the prediction of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2010;50(1):162–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.11.046.

Chincarini A, Bosco P, Calvini P, Gemme G, Esposito M, Olivieri C, et al. Local MRI analysis approach in the diagnosis of early and prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2011;58(2):469–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.083.

Costafreda SG, Dinov ID, Tu Z, Shi Y, Liu CY, Kloszewska I, et al. Automated hippocampal shape analysis predicts the onset of dementia in mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage. 2011;56(1):212–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.01.050.

Filipovych R, Davatzikos C. Semi-supervised pattern classification of medical images: application to mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Neuroimage. 2011;55(3):1109–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.12.066.

Westman E, Simmons A, Zhang Y, Muehlboeck JS, Tunnard C, Liu Y, et al. Multivariate analysis of MRI data for Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment and healthy controls. Neuroimage. 2011;54(2):1178–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.08.044.

Wolz R, Julkunen V, Koikkalainen J, Niskanen E, Zhang DP, Rueckert D, et al. Multi-method analysis of MRI images in early diagnostics of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e25446.

Zhang D, Wang Y, Zhou L, Yuan H, Shen D. Multimodal classification of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage. 2011;55(3):856–67.

Batmanghelich NK, Taskar B, Davatzikos C. Generative-discriminative basis learning for medical imaging. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2012;31(1):51–69.

Cheng B, Zhang D, Shen D. Domain transfer learning for MCI conversion prediction. In: Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics). Berlin: Springer Verlag; 2012. p. 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-33415-3_11.

Cho Y, Seong JK, Jeong Y, Shin SY. Individual subject classification for Alzheimer’s disease based on incremental learning using a spatial frequency representation of cortical thickness data. Neuroimage. 2012;59(3):2217–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.085.

Gray KR, Wolz R, Heckemann RA, Aljabar P, Hammers A, Rueckert D. Multi-region analysis of longitudinal FDG-PET for the classification of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2012;60(1):221–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.12.071.

Li Y, Wang Y, Wu G, Shi F, Zhou L, Lin W, et al. Discriminant analysis of longitudinal cortical thickness changes in Alzheimer’s disease using dynamic and network features. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(2):427.e15–30.

Toussaint PJ, Perlbarg V, Bellec P, Desarnaud S, Lacomblez L, Doyon J, et al. Resting state FDG-PET functional connectivity as an early biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease using conjoint univariate and independent component analyses. Neuroimage. 2012;63(2):936–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.091.

Wee CY, Yap PT, Zhang D, Denny K, Browndyke JN, Potter GG, et al. Identification of MCI individuals using structural and functional connectivity networks. Neuroimage. 2012;59(3):2045–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.015.

Ye J, Farnum M, Yang E, Verbeeck R, Lobanov V, Raghavan N, et al. Sparse learning and stability selection for predicting MCI to AD conversion using baseline ADNI data. BMC Neurol. 2012;25(1):12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-12-46.

Adaszewski S, Dukart J, Kherif F, Frackowiak R, Draganski B. How early can we predict Alzheimer’s disease using computational anatomy? Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34(12):2815–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.06.015.

Aguilar C, Westman E, Muehlboeck JS, Mecocci P, Vellas B, Tsolaki M, et al. Different multivariate techniques for automated classification of MRI data in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Psychiatry Res - Neuroimaging. 2013;212(2):89–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2012.11.005.

Babu GS, Suresh S, Mahanand BS. Meta-cognitive q-Gaussian RBF network for binary classification: application to mild cognitive impairment (MCI). In: Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks; 2013.

Casanova R, Hsu FC, Sink KM, Rapp SR, Williamson JD, Resnick SM, et al. Alzheimer’s disease risk assessment using large-scale machine learning methods. PLoS One. 2013;8(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0077949.

Cheng B, Zhang D, Jie B, Shen D. Sparse multimodal manifold-regularized transfer learning for MCI conversion prediction. In: Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics). Switzerland: Springer Verlag; 2013. p. 251–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02267-3_32.

Liu M, Il SH, Shen D. Multi-task sparse classifier for diagnosis of MCI conversion to AD with longitudinal MR images. In: Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics). Switzerland: Springer Verlag; 2013. p. 243–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02267-3_31.

Liu X, Tosun D, Weiner MW, Schuff N. Locally linear embedding (LLE) for MRI based Alzheimer’s disease classification. Neuroimage. 2013;83:148–57 [cited 2019 Nov 14] Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1053811913006708.

Wee CY, Yap PT, Shen D. Prediction of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment using cortical morphological patterns. Hum Brain Mapp. 2013;34(12):3411–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.22156.

Young J, Modat M, Cardoso MJ, Mendelson A, Cash D, Ourselin S. Accurate multimodal probabilistic prediction of conversion to Alzheimer’s disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment. NeuroImage Clin. 2013;2:735–45.

Apostolova LG, Hwang KS, Kohannim O, Avila D, Elashoff D, Jack CR, et al. ApoE4 effects on automated diagnostic classifiers for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroImage Clin. 2014;4:461–72.

Guerrero R, Wolz R, Rao AW, Rueckert D. Manifold population modeling as a neuro-imaging biomarker: application to ADNI and ADNI-GO. Neuroimage. 2014;94:275–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.03.036.

Lebedev AV, Westman E, Van Westen GJP, Kramberger MG, Lundervold A, Aarsland D, et al. Random forest ensembles for detection and prediction of Alzheimer’s disease with a good between-cohort robustness. NeuroImage Clin. 2014;6:115–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2014.08.023.

Liu M, Zhang D, Shen D. Identifying informative imaging biomarkers via tree structured sparse learning for AD diagnosis. Neuroinformatics. 2014;12(3):381–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12021-013-9218-x.

Liu F, Wee CY, Chen H, Shen D. Inter-modality relationship constrained multi-modality multi-task feature selection for Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment identification. Neuroimage. 2014;84:466–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.09.015.

Min R, Wu G, Cheng J, Wang Q, Shen D. Multi-atlas based representations for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35(10):5052–70 [cited 2019 Nov 11] Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/hbm.22531.

Suk HI, Lee SW, Shen D. Hierarchical feature representation and multimodal fusion with deep learning for AD/MCI diagnosis. Neuroimage. 2014;101:569–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.06.077.

Tong T, Wolz R, Gao Q, Guerrero R, Hajnal JV, Rueckert D. Multiple instance learning for classification of dementia in brain MRI. Med Image Anal. 2014;18(5):808–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2014.04.006.

Cabral C, Morgado PM, Campos Costa D, Silveira M. Predicting conversion from MCI to AD with FDG-PET brain images at different prodromal stages. Comput Biol Med. 2015;58:101–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2015.01.003.

Cheng B, Liu M, Suk HI, Shen D, Zhang D. Multimodal manifold-regularized transfer learning for MCI conversion prediction. Brain Imaging Behav. 2015;9(4):913–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-015-9356-x.

Cheng B, Liu M, Zhang D, Munsell BC, Shen D. Domain transfer learning for MCI conversion prediction. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2015;62(7):1805–17. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2015.2404809.

Moradi E, Pepe A, Gaser C, Huttunen H, Tohka J. Machine learning framework for early MRI-based Alzheimer’s conversion prediction in MCI subjects. Neuroimage. 2015;104:398–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.10.002.

Raamana PR, Weiner MW, Wang L, Beg MF. Thickness network features for prognostic applications in dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36(S1):S91–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.05.040.

Ritter K, Schumacher J, Weygandt M, Buchert R, Allefeld C, Haynes JD. Multimodal prediction of conversion to Alzheimer’s disease based onincomplete biomarkers. Alzheimer’s Dement Diagnosis, Assess Dis Monit. 2015;1(2):206–15.

Salvatore C, Cerasa A, Battista P, Gilardi MC, Quattrone A, Castiglioni I. Magnetic resonance imaging biomarkers for the early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a machine learning approach. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:307.

Xu L, Wu X, Chen K, Yao L. Multi-modality sparse representation-based classification for Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2015;122(2):182–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2015.08.004.

Ardekani BA, Bermudez E, Mubeen AM, Bachman AH. Prediction of incipient Alzheimer’s disease dementia in patients with mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016;55(1):269–81. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-160594.

Capecci E, Doborjeh ZG, Mammone N, La Foresta F, Morabito FC, Kasabov N. Longitudinal study of Alzheimer’s disease degeneration through EEG data analysis with a NeuCube spiking neural network model. In: Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks; 2016.

Collij LE, Heeman F, Kuijer JPA, Ossenkoppele R, Benedictus MR, Möller C, et al. Application of machine learning to arterial spin labeling in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Radiology. 2016;281(3):865–75. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2016152703.

Li Y, Wang X, Li Y, Sun Y, Sheng C, Li H, et al. Abnormal resting-state functional connectivity strength in mild cognitive impairment and its conversion to Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Plast. 2016 [cited 2019 Nov 11]; Available from:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/4680972.

Liu M, Zhang D, Shen D. Relationship induced multi-template learning for diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2016;35(6):1463–74. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2016.2515021.

López ME, Turrero A, Cuesta P, López-Sanz D, Bruña R, Marcos A, et al. Searching for primary predictors of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease: a multivariate follow-up study. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016;52(1):133–43. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-151034.

Suk HI, Lee SW, Shen D. Deep sparse multi-task learning for feature selection in Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. Brain Struct Funct. 2016;221(5):2569–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-015-1059-y.

Thung KH, Wee CY, Yap PT, Shen D. Identification of progressive mild cognitive impairment patients using incomplete longitudinal MRI scans. Brain Struct Funct. 2016;221(8):3979–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-015-1140-6.

Vasta R, Augimeri A, Cerasa A, Nigro S, Gramigna V, Nonnis M, et al. Hippocampal subfield atrophies in converted and not-converted mild cognitive impairments patients by a Markov random fields algorithm. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2016;13(5):566–74 [cited 2021 Jun 3] Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26787291/.

Zhang J, Shi J, Stonnington C, Li Q, Gutman BA, Chen K, et al. Hyperbolic space sparse coding with its application on prediction of Alzheimer’s disease in mild cognitive impairment. In: Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics): Springer Verlag; 2016. p. 326–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02267-3_31.

Zhang J, Stonnington C, Li Q, Shi J, Bauer RJ, Gutman BA, et al. Applying sparse coding to surface multivariate tensor-based morphometry to predict future cognitive decline. In: Proceedings - International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging. Prague: IEEE Computer Society; 2016. p. 646–50. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISBI.2016.7493350.

Çitak-Er F, Goularas D, Ormeci B. A novel convolutional neural network model based on voxel-based morphometry of imaging data in predicting the prognosis of patients with mild cognitive impairment. J Neurol Sci. 2017;34(1):52–69.

Hojjati SH, Ebrahimzadeh A, Khazaee A, Babajani-Feremi A. Predicting conversion from MCI to AD using resting-state fMRI, graph theoretical approach and SVM. J Neurosci Methods. 2017;282:69–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2017.03.006.

Long X, Chen L, Jiang C, Zhang L. Prediction and classification of Alzheimer disease based on quantification of MRI deformation. PLoS One. 2017;12(3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173372.

Mathotaarachchi S, Pascoal TA, Shin M, Benedet AL, Kang MS, Beaudry T, et al. Identifying incipient dementia individuals using machine learning and amyloid imaging. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;59:80–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.06.027.

Suk HI, Lee SW, Shen D. Deep ensemble learning of sparse regression models for brain disease diagnosis. Med Image Anal. 2017;37:101–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2017.01.008.

Tong T, Gao Q, Guerrero R, Ledig C, Chen L, Rueckert D. A novel grading biomarker for the prediction of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2017;64(1):155–65. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2016.2549363.

Choi H, Jin KH. Predicting cognitive decline with deep learning of brain metabolism and amyloid imaging. Behav Brain Res. 2018;344:103–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2018.02.017.

Donnelly-Kehoe PA, Pascariello GO, Gómez JC. Looking for Alzheimer’s disease morphometric signatures using machine learning techniques. J Neurosci Methods. 2018;302:24–34.

Gao N, Tao LX, Huang J, Zhang F, Li X, O’Sullivan F, et al. Contourlet-based hippocampal magnetic resonance imaging texture features for multivariant classification and prediction of Alzheimer’s disease. Metab Brain Dis. 2018;33(6):1899–909. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11011-018-0296-1.

Gómez-Sancho M, Tohka J, Gómez-Verdejo V. Comparison of feature representations in MRI-based MCI-to-AD conversion prediction. Magn Reson Imaging. 2018;50:84–95 [cited 2021 Jun 7] Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29530541/.

Hojjati SH, Ebrahimzadeh A, Khazaee A, Babajani-Feremi A. Predicting conversion from MCI to AD by integrating rs-fMRI and structural MRI. Comput Biol Med. 2018;102:30–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2018.09.004.

Khanna S, Domingo-Fernández D, Iyappan A, Emon MA, Hofmann-Apitius M, Fröhlich H. Using multi-scale genetic, neuroimaging and clinical data for predicting Alzheimer’s disease and reconstruction of relevant biological mechanisms. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29433-3.

Lin W, Tong T, Gao Q, Guo D, Du X, Yang Y, et al. Convolutional neural networks-based MRI image analysis for the Alzheimer’s disease prediction from mild cognitive impairment. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:777.

Liu J, Li M, Lan W, Wu FX, Pan Y, Wang J. Classification of Alzheimer’s disease using whole brain hierarchical network. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinforma. 2018;15(2):624–32.

Liu M, Gao Y, Yap PT, Shen D. Multi-hypergraph learning for incomplete multimodality data. IEEE J Biomed Heal Informatics. 2018;22(4):1197–208. https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2017.2732287.

Lu D, Popuri K, Ding GW, Balachandar R, Beg MF, Weiner M, et al. Multimodal and multiscale deep neural networks for the early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease using structural MR and FDG-PET images. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1, 1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-22871-z.

Minhas S, Khanum A, Riaz F, Khan SA, Alvi A. Predicting progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease using autoregressive modelling of longitudinal and multimodal biomarkers. IEEE J Biomed Heal Informatics. 2018;22(3):818–25. https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2017.2703918.

Popuri K, Balachandar R, Alpert K, Lu D, Bhalla M, Mackenzie IR, et al. Development and validation of a novel dementia of Alzheimer’s type (DAT) score based on metabolism FDG-PET imaging. NeuroImage Clin. 2018;18:802–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2018.03.007.

Sørensen L, Nielsen M. Ensemble support vector machine classification of dementia using structural MRI and mini-mental state examination. J Neurosci Methods. 2018;302:66–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2018.01.003.

Sun Z, Qiao Y, Lelieveldt BPF, Staring M. Integrating spatial-anatomical regularization and structure sparsity into SVM: improving interpretation of Alzheimer’s disease classification. Neuroimage. 2018;178:445–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.05.051.

Wu C, Guo S, Hong Y, Xiao B, Wu Y, Zhang Q. Discrimination and conversion prediction of mild cognitive impairment using convolutional neural networks. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2018;8(10):992–1003. https://doi.org/10.21037/qims.2018.10.17.

Yan Y, Lee H, Somer E, Grau V. Generation of amyloid PET images via conditional adversarial training for predicting progression to Alzheimer’s disease; 2018. p. 26–33.

Basaia S, Agosta F, Wagner L, Canu E, Magnani G, Santangelo R, et al. Automated classification of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment using a single MRI and deep neural networks. NeuroImage Clin. 2019;21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2018.101645.

Cheng B, Liu M, Zhang D, Shen D. Robust multi-label transfer feature learning for early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Imaging Behav. 2019;13(1):138–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-018-9846-8.

Collazos-Huertas D, Cárdenas-Peña D, Castellanos-Dominguez G. Instance-based representation using multiple kernel learning for predicting conversion to Alzheimer disease. In: International Journal of Neural Systems: World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte Ltd; 2019. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0129065718500429.

Elahifasaee F, Li F, Yang M. A Classification algorithm by combination of feature decomposition and kernel discriminant analysis (KDA) for automatic MR brain image classification and AD diagnosis. Comput Math Methods Med. 2019;2019:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/1437123.

Ezzati A, Zammit AR, Harvey DJ, Habeck C, Hall CB, Lipton RB. Optimizing machine learning methods to improve predictive models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019;71(3):1027–36. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-190262.

Gupta Y, Lama RK, Kwon G-R. Prediction and classification of Alzheimer’s disease based on combined features from apolipoprotein-E genotype, cerebrospinal fluid, MR, and FDG-PET imaging biomarkers. Front Comput Neurosci. 2019;13 [cited 2019 Nov 11] Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fncom.2019.00072/full.

Lee G, Nho K, Kang B, Sohn KA, Kim D, Weiner MW, et al. Predicting Alzheimer’s disease progression using multi-modal deep learning approach. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-37769-z.

Lee E, Choi J-S, Kim M, Suk H-I. Toward an interpretable Alzheimer’s disease diagnostic model with regional abnormality representation via deep learning. Neuroimage. 2019;202:116113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116113.

Lei B, Hou W, Zou W, Li X, Zhang C, Wang T. Longitudinal score prediction for Alzheimer’s disease based on ensemble correntropy and spatial–temporal constraint. Brain Imaging Behav. 2019;13(1):126–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-018-9834-z.

Li H, Habes M, Wolk DA, Fan Y. A deep learning model for early prediction of Alzheimer’s disease dementia based on hippocampal magnetic resonance imaging data. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2019;15(8):1059–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2019.02.007.

Li Y, Fang Y, Zhang H, Hu B. Self-weighting grading biomarker based on graph-guided information propagation for the prediction of mild cognitive impairment conversion. IEEE Access. 2019;7:116632–42. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2936415.

Oh K, Chung YC, Kim KW, Kim WS, Oh IS. Classification and visualization of Alzheimer’s disease using volumetric convolutional neural network and transfer learning. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54548-6.

Pan X, Adel M, Fossati C, Gaidon T, Guedj E. Multilevel feature representation of FDG-PET brain images for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease. IEEE J Biomed Heal Informatics. 2019;23(4):1499–506. https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2018.2857217.

Pusil S, Dimitriadis SI, López ME, Pereda E, Maestú F. Aberrant MEG multi-frequency phase temporal synchronization predicts conversion from mild cognitive impairment-to-Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroImage Clin. 2019;24:101972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101972.

Spasov S, Passamonti L, Duggento A, Liò P, Toschi N. A parameter-efficient deep learning approach to predict conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2019;189:276–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.01.031.

Wang Y, Xu C, Park JH, Lee S, Stern Y, Yoo S, et al. Diagnosis and prognosis of Alzheimer’s disease using brain morphometry and white matter connectomes. NeuroImage Clin. 2019;23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101859.

Wee CY, Liu C, Lee A, Poh JS, Ji H, Qiu A. Cortical graph neural network for AD and MCI diagnosis and transfer learning across populations. NeuroImage Clin. 2019;23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101929.

Xu L, Yao Z, Li J, Lv C, Zhang H, Hu B. Sparse feature learning with label information for Alzheimer’s disease classification based on magnetic resonance imaging. IEEE Access. 2019;7:26157–67. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2894530.

Zhou T, Liu M, Thung KH, Shen D. Latent representation learning for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis with incomplete multi-modality neuroimaging and genetic data. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2019;38(10):2411–22. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2019.2913158.

Zhu X, Suk H. Il, Shen D. Low-rank dimensionality reduction for multi-modality neurodegenerative disease identification. World Wide Web. 2019;22(2):907–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11280-018-0645-3.

Abrol A, Bhattarai M, Fedorov A, Du Y, Plis S, Calhoun V. Deep residual learning for neuroimaging: an application to predict progression to Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci Methods. 2020;339:108701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2020.108701.

Gao F, Yoon H, Xu Y, Goradia D, Luo J, Wu T, et al. AD-NET: Age-adjust neural network for improved MCI to AD conversion prediction. NeuroImage Clin. 2020;27:102290.

Giorgio J, Landau SM, Jagust WJ, Tino P, Kourtzi Z. Modelling prognostic trajectories of cognitive decline due to Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroImage Clin. 2020;26:102199.

Khatri U, Kwon GR, Rostro-Gonzalez H. An efficient combination among sMRI, CSF, cognitive score, and APOE ϵ 4 biomarkers for classification of AD and MCI using extreme learning machine. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2020;2020:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8015156.

Lin W, Gao Q, Yuan J, Chen Z, Feng C, Chen W, et al. Predicting Alzheimer’s disease conversion from mild cognitive impairment using an extreme learning machine-based grading method with multimodal data. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:77.

Lin Y, Huang K, Xu H, Qiao Z, Cai S, Wang Y, et al. Predicting the progression of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease by longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging-based dictionary learning. Clin Neurophysiol. 2020;131(10):2429–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2020.07.016.

Pan D, Zeng A, Jia L, Huang Y, Frizzell T, Song X. Early detection of Alzheimer’s disease using magnetic resonance imaging: a novel approach combining convolutional neural networks and ensemble learning. Front Neurosci. 2020;14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.00259.

Ramon-Julvez U, Hernandez M, Mayordomo E. Analysis of the influence of diffeomorphic normalization in the prediction of stable vs progressive MCI conversion with convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings - International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging; 2020.

Xiao R, Cui X, Qiao H, Zheng X, Zhang Y. Early diagnosis model of Alzheimer’s disease based on sparse logistic regression. Multimed Tools Appl. 2020:1–12. Available from. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-020-09738-0.

Xu M, Sanz DL, Garces P, Maestu F, Li Q, Pantazis D. A graph Gaussian embedding method for predicting Alzheimer’s disease progression with MEG brain networks. arXiv; 2020.

Yang Z, Liu Z. The risk prediction of Alzheimer’s disease based on the deep learning model of brain 18F-FDG positron emission tomography. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2020;27(2):659–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2019.12.004.

Yee E, Popuri K, Beg MF. Quantifying brain metabolism from FDG-PET images into a probability of Alzheimer’s dementia score. Hum Brain Mapp. 2020;41(1):5–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.24783.

Zhou T, Thung KH, Liu M, Shi F, Zhang C, Shen D. Multi-modal latent space inducing ensemble SVM classifier for early dementia diagnosis with neuroimaging data. Med Image Anal. 2020:60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2019.101630.

Bae J, Stocks J, Heywood A, Jung Y, Jenkins L, Hill V, et al. Transfer learning for predicting conversion from mild cognitive impairment to dementia of Alzheimer’s type based on a three-dimensional convolutional neural network. Neurobiol Aging. 2021;99:53–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2020.12.005.

Mofrad SA, Lundervold AJ, Vik A, Lundervold AS. Cognitive and MRI trajectories for prediction of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Reports. 11:2122. 123AD [cited 2021 Jun 11] Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-78095-7

Mofrad SA, Lundervold A, Lundervold AS. A predictive framework based on brain volume trajectories enabling early detection of Alzheimer’s disease. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2021:90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compmedimag.2021.101910.

Pan X, Le Phan T, Adel M, Fossati C, Gaidon T, Wojak J, et al. Multi-view separable pyramid network for AD prediction at MCI stage by 18F-FDG brain PET imaging. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2021;40(1):81–92. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2020.3022591.

Shen HT, Zhu X, Zhang Z, Wang SH, Chen Y, Xu X, et al. Heterogeneous data fusion for predicting mild cognitive impairment conversion. Inf Fusion. 2021;66:54–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2020.08.023.

Syaifullah AH, Shiino A, Kitahara H, Ito R, Ishida M, Tanigaki K. Machine learning for diagnosis of AD and prediction of MCI progression from brain MRI using brain anatomical analysis using diffeomorphic deformation. Front Neurol. 2021;11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.576029.

Wen J, Samper-González J, Bottani S, Routier A, Burgos N, Jacquemont T, et al. Reproducible evaluation of diffusion MRI features for automatic classification of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroinformatics. 2021;19(1):57–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12021-020-09469-5.

Zhang J, Zheng B, Gao A, Feng X, Liang D, Long X. A 3D densely connected convolution neural network with connection-wise attention mechanism for Alzheimer’s disease classification. Magn Reson Imaging. 2021;78:119–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2021.02.001.

Zhu Y, Kim M, Zhu X, Kaufer D, Wu G. Long range early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease using longitudinal MR imaging data. Med Image Anal. 2021:67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2020.101825.

Steardo L, Carbone EA, de Filippis R, Pisanu C, Segura-Garcia C, Squassina A, et al. Application of support vector machine on fmri data as biomarkers in schizophrenia diagnosis: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00588.

Metz CE. Receiver operating characteristic analysis: a tool for the quantitative evaluation of observer performance and imaging systems. J Am Coll Radiol. 2006;3(6):413–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2006.02.021.

Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143(1):29–36. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747.

Ebrahimighahnavieh MA, Luo S, Chiong R. Deep learning to detect Alzheimer’s disease from neuroimaging: a systematic literature review. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2020;187:105242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2019.105242.

Chan D, Fox NC, Scahill RI, Crum WR, Whitwell JL, Leschziner G, et al. Patterns of temporal lobe atrophy in semantic dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2001;49(4):433–42.

Fan Y, Batmanghelich N, Clark CM, Davatzikos C. Spatial patterns of brain atrophy in MCI patients, identified via high-dimensional pattern classification, predict subsequent cognitive decline. Neuroimage. 2008;39(4):1731–43.

Jack CR, Petersen RC, Xu Y, O’Brien PC, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, et al. Rate of medial temporal lobe atrophy in typical aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1998;51(4):993–9.

Lerch JP, Pruessner J, Zijdenbos AP, Collins DL, Teipel SJ, Hampel H, et al. Automated cortical thickness measurements from MRI can accurately separate Alzheimer’s patients from normal elderly controls. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29(1):23–30.

Singh V, Chertkow H, Lerch JP, Evans AC, Dorr AE, Kabani NJ. Spatial patterns of cortical thinning in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 11):2885–93.

Mattila J, Soininen H, Koikkalainen J, Rueckert D, Wolz R, Waldemar G, et al. Optimizing the diagnosis of early Alzheimer’s disease in mild cognitive impairment subjects. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2012;32(4):969–79. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-2012-120934.

Acknowledgements

We want to acknowledge the eHealth Center of the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC) for funding the publication of this article.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SG conceived the original idea for the review, designed the search strategy, performed the search, article selection, and data extraction, also wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and contributed to the subsequent reviews and final version. RVS supervised the review process, made an independent article screening, revised the manuscript, and contributed to writing of the final version. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Grueso, S., Viejo-Sobera, R. Machine learning methods for predicting progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease dementia: a systematic review. Alz Res Therapy 13, 162 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-021-00900-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-021-00900-w