Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this review was to investigate whether there is a faster cognitive decline in dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) than in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) over time.

Methods

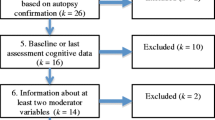

PsycINFO and Medline were searched from 1946 to February 2013. A quality rating from 1 to 15 (best) was applied to the included studies. A quantitative meta-analysis was done on studies with mini mental state examination (MMSE) as the outcome measure.

Results

A total of 18 studies were included. Of these, six (36%) reported significant differences in the rate of cognitive decline. Three studies reported a faster cognitive decline on MMSE in patients with mixed DLB and AD compared to pure forms, whereas two studies reported a faster decline on delayed recall and recognition in AD and one in DLB on verbal fluency. Mean quality scores for studies that did or did not differ were not significantly different. Six studies reported MMSE scores and were included in the meta-analysis, which showed no significant difference in annual decline on MMSE between DLB (mean 3.4) and AD (mean 3.3).

Conclusions

Our findings do not support the hypothesis of a faster rate of cognitive decline in DLB compared to AD. Future studies should apply recent diagnostic criteria, as well as extensive diagnostic evaluation and ideally autopsy diagnosis. Studies with large enough samples, detailed cognitive tests, at least two years follow up and multivariate statistical analysis are also needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are the two most common subtypes of neurodegenerative dementia, representing 15 to 20% and 65% of all dementia cases, respectively [1]. DLB is characterized clinically by symptoms such as visual hallucinations, Parkinsonism and fluctuating cognition in addition to cognitive impairment with typically more visuospatial and executive impairment relative to memory impairment [2]. There is some evidence that DLB patients have more rapidly progressing dementia compared to AD [3], and more recent studies also reported a more severe course with shorter survival [4], higher rate of nursing home admissions [5] and higher costs in DLB as compared to AD [6].

An overlap in neuropathology between AD and DLB has been noted [7]. Parkinson’s disease (PD) and DLB also share some clinical and pathological features [8]. Subgroups with different cognitive profiles have been described in patients with PD [9], and there is evidence that this differentiation is related to the rate of cognitive decline [10]. Similar neuropsychologically defined subgroups may exist also in DLB [8], which could also predict differences in the rate of progression to end-stage dementia. Data supports accelerated disease progression when AD and DLB pathologies are present together [11].

To our knowledge, no systematic review has compared rate of cognitive decline in DLB versus AD. We therefore systematically reviewed the literature to find studies assessing overall cognitive decline in DLB and AD. We specifically noted studies that had investigated the potential differences in cognitive decline in subgroups with DLB and the effect of employing different diagnostic criteria.

Methods

PsycINFO and Medline were searched in February 2013, using key words listed in Table 11. References from reviewed articles were also searched for relevant studies. The following inclusion criteria were used: a) paper published in a peer-reviewed journal; b) written in English; c) DLB or mixed AD/DLB compared with AD; d) application of at least one neuropsychological test, and e) at least 6 months follow up. The following exclusion criteria were used: a) drug trials, and b) survival studies with death as the only outcome.

Quality assessment

Two independent raters rated all studies with a self-designed quality scale and arrived at the same result. The domains, a) number of patients included; b) follow-up time; c) clinical criteria; d) autopsy, and e) neuropsychological tests) were rated on a four-point scale adapted from Aarsland et al. (2005) [12]: 0 (none), 1 (poor), 2 (fair) and 3 (good). See Table 22. Studies could be assigned 1 to 15 points.

Statistical analysis

For studies reporting mini mental state examination (MMSE) results, standardized mean difference in annual progression between DLB and AD was calculated as the difference between annual progression between the DLB and AD groups divided by the pooled standard deviation across groups in each included study. The standardized mean differences were combined in a random-effects model to obtain summary estimates of the effect in each study. The overall results from each trial were then combined using a random-effects model to obtain a pooled summary estimate of effect across all trials [13]. To assess heterogeneity, the I 2 as proposed by Higgins and colleagues [14] was chosen, indicating the percentage of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity.

Results

Of the 18 studies included in this review (see Table 33), six (36%) reported a statistically significant difference in cognitive decline over time between AD and DLB (see Table 14). Three studies reported a faster cognitive decline on cognitive screening tests in the neuropathologically mixed AD/DLB group [3],[15],[16] compared to those with pure AD or DLB. One study reported a faster decline in DLB than in AD on verbal fluency [17], and two in AD compared to DLB on memory [18],[19]. For a full description of neuropsychological tests used in included studies, see Table 33.

Six studies either reported annual decline in MMSE scores, or included data enabling calculation of annual decline based on reported scores. In AD, mean annual decline was 3.3 (SD 1.7, range 1.8 to 4.9), and in DLB 3.4 (SD 1.4, range 1.8 to 5.8). One study also reported annual decline of 5.0 in AD/DLB (see Figure 11). The random-effects meta-analysis revealed an overall effect-size of −0.035 (negative sign indicates faster progression in DLB) (P = 0.764; 95% CI = 0.261, 0.192). I 2 was 50.3, which is considered to represent moderate heterogeneity [14].

Cognitive domains

Six studies measured memory, and two reported differences in memory over time, both a faster decline in AD. Delayed recall was found to have a faster decline in AD compared to AD/DLB when measured with the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) evaluation, with 15% of patients with AD versus 32% of patients with AD/DLB remembering any item at the last evaluation [17]. Recognition was found to have a faster decline in AD compared to DLB as measured with Hopkins verbal learning test- revised (HVLT-R) (scores not available) [19]. Eight studies measuring language and ten studies measuring visuospatial ability reported no differences in rate of decline. Seven studies measured explicit executive functions, and one reported differences over time. In that study, verbal fluency was found to have a more rapid decline in DLB compared to AD, measured with the Cambride cognitive examination (CAMCOG) (subscores not available) [17].

Subgroups

Two studies [28],[30] divided patients into two groups according to high or low visuospatial functioning. In the first study, DLB patients with a low baseline score (<20) on the Wechsler intelligence scale for children-revised, block design (WISC-R) and impaired clock drawing test (CDT) had a faster decline on the dementia rating scale (DRS), compared to DLB patients with a high baseline score. In the latter study, DLB patients with a low baseline score on the Newcastle visual perception battery (NEVIP) had a faster decline in activities of daily living (ADL) than those with higher score, but no difference on any of the cognitive tests. There were no differences in the AD groups.

Quality assessment

The mean quality score for all the included studies was 9.4 points (SD 2.5, range 5 to 14) (see Table 55). Only two studies were rated fair or good on all quality measures [26],[27]. Three studies were rated poor on one variable, but fair and good on the others [15],[16],[22]. Mean quality scores for studies that found any differences in cognitive decline was 9.8 points (SD 2.4, range 5 to 11) compared to 9.3 points (SD 2.6, range 5 to 14) in the group with no differences (P = 0.335).

Clinical and neuropathological diagnostic criteria

There were no systematical differences in clinical or neuropathological criteria between studies that found differences in cognitive decline and those who did not (see Table 66). Of 18 included studies, 16 (89%) used National Institute of Neurological and Communication Disorders and Stroke/Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS/ADRDA) or CERAD clinical criteria for AD and 12 (67%) used DLB consensus criteria, only one of them used the revised criteria from 2005. To diagnose AD neuropathologically, mainly CERAD neuropathological criteria for the diagnosis of AD and neuropathological DLB consensus criteria from 1996 were used. A diagnosis of mixed AD/DLB was made, if in addition to the Alzheimer’s pathology the characteristic Lewy bodies were found in subcortical and cortical areas. Eleven studies (61%) used autopsy-confirmed diagnosis on all patients. In three studies (17%), some of the diagnoses were autopsy-confirmed. In four studies (22%) autopsy was not performed. One of the studies used 123I-FP-CIT-SPECT only as a method of verifying of clinical diagnosis [31].

Discussion

In the 18 studies included in this review, no consistent faster rate of decline in DLB as compared to AD on cognitive screening tests was found. When combining studies that used MMSE, the most frequently used scale, a meta-analysis revealed no difference in the annual rate of cognitive decline. There were mixed findings on decline in specific cognitive domains. Two of six studies of memory found a more rapid decline in AD. Only one of seven studies of executive function found a more rapid decline in DLB, and differences in visuospatial or language tests were not found. The hypothesis of a more rapid cognitive decline in autopsied patients with both AD and DLB pathology was supported in three studies. However, findings were inconsistent and other studies did not find differences.

Differences in methods such as selection criteria, design, neuropsychological tests, dementia severity, diagnostic procedures and criteria can explain the diverse findings and lack of firm conclusions. However, quality assessment did not reveal any systematic differences between studies with high or low quality scores. There were large differences in sample sizes (n = 28 to 315), and the studies that could not be included in the meta-analysis or used other tests than MMSE, thus, may have had varying statistical power to detect significant differences between groups. To be able to compare the overall results and draw some general conclusions it would have been ideal that uniform diagnostic criteria had been used in all the studies. Some of the studies initially included patients with a clinical diagnosis of AD only, where analyses were based on autopsy diagnosis which included both AD and DLB.

A common weakness in the included studies was the choice of neuropsychological measures. When studying cognitive decline over time, cognitive tests that are designed for a specific cognitive domain are required. Screening tests or batteries that use a total score only, often designed for purposes other than research are less suitable. In this review, the MMSE was the most used test, either alone, or in combination with others. The MMSE may not be an optimal measure, especially when using only the total score and not separate subscores for different cognitive domains, as AD and DLB have different cognitive profiles at onset [32]. This difference in cognitive profile leads to difficulties in choosing an optimal cognitive screening instrument to compare AD and DLB. The MMSE is heavily based on memory and language and is thus more sensitive to changes in AD than in DLB [33]. DLB is associated with a more severe visuospatial deficit than AD [32],[34], but only 1 of 30 points on the MMSE comes from a measure of visuospatial functioning. MMSE may also be less than optimal because of the ceiling and floor effect [35], which refers to a test being too easy or too difficult to discriminate below or above a certain point, which is a common problem when testing people with dementia. In one of the reviewed studies the children’s version of the Wechsler intelligence scale was used to avoid this. The test then lacks age adjusted norms, but it gains a wider range in scores, and therefore can monitor the cognitive decline over a longer period of time. Studies differed also with regard to the time period of observation, from 1 to 20 years. In studies with short follow-up periods, the MMSE may not be a reliable measure, as Clark, Sheppard, Fillenbaum et al. (1999) [36] have argued that MMSE registrations need to be separated by at least three years in order to be a reliable measure of cognitive decline in AD.

Only few studies investigated, or reported, subgroups with different cognitive profiles in DLB. It could be due to a low number of cases in several studies, and subsequent low statistical power. People die from dementia or reach an endpoint where they are not capable of performing cognitive tests, and therefore in several studies there was a lower number of patients towards the end of the study. This is challenging when performing statistical analysis. Our search did not cover the issue of subgroups with different cognitive profiles thoroughly, as we only included studies comparing DLB with AD, and not studies describing cognitive decline in DLB and potential subgroups alone. However, there are some data that support the hypothesis that there are subgroups in DLB with different cognitive profiles, and subgroups with poor initial visuospatial function may have a more rapid decline than DLB with good visuospatial function [28].

Due to overlapping symptoms, it can be difficult to determine the correct diagnosis ante mortem between the pure form of AD, mixed AD/DLB and the pure form of DLB. Because clinical criteria cannot distinguish with certainty the individual pathology, the gold standard for validating the clinical assessment is neuropathological diagnosis. Clinical criteria may have a low sensitivity in particular for DLB, which could have been a source of bias in studies that did not include a neuropathological validation of the diagnosis. However, dementia is a clinical diagnosis and both AD and DLB pathology can be found also in cognitively normal elderly subjects. In one study with autopsy, 50% of cases with widespread α-synucleinopathy did not show any clinical signs of dementia [37].

In most studies with autopsy, consensus neuropathological criteria were used. Even though not all included studies used consistent and the same neuropathological methods and criteria, and many also used varying combinations, use of post-mortem verification at least increases the validity of the clinical diagnosis.

It is also important to mention that the sensitivity for detecting Lewy bodies has increased with anti-ubiquitin immunostaining, where tau-positive samples indicate Alzheimer’s pathology. Anti-α-synuclein immunostaining has been incorporated in the assessment, which is most sensitive for Lewy body pathology [2]. Thus, the neuropathological identification of cases may have been less accurate before the new methods were established, and more reliable staging strategies have been developed [38].

A complicating issue is the frequent occurrence of mixed pathology [39], and to underline the complexity of dementia and its pathology, at least four distinct pathological phenotypes have been identified between AD and DLB [40]. According to Schneider et al. (2012) [7], the locus of neuropathology is associated with a faster decline in cognition. A neocortical type of Lewy body pathology is associated with increased odds of dementia and a faster decline in episodic, semantic and working memory. The limbic-type is more associated with more rapid decline in visuospatial function. Olichney et al. (1998) [3], concluded that patients with Lewy body variant decline faster than patients with Alzheimer’s disease. This statement has often been used with reference to rapid progression in DLB, but it actually refers to an AD variant with Lewy body pathology, not to pure DLB. It should be emphasized that it is still uncertain whether AD and DLB are two independent pathologies that may coexist, or the pathologies are related, or one of them is a consequence of the other.

Conclusion

Only 6 of the 18 included studies in this review found some differences in cognitive decline between DLB and AD over time, and only one of them found a faster decline in DLB. It is difficult to draw firm conclusions based on available studies, since the results are contradictory. Future studies will need to apply recent diagnostic criteria, as well as extensive diagnostic evaluation and autopsy to confirm the diagnosis. Studies with large enough samples, adapted cognitive tests, more than one year of follow up and multivariate statistical analysis are also needed. Inclusion of mild cognitive impairment patients, with subclinical manifestations and an increased risk of developing DLB (for example, who present rapid eye-movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder) could also strengthen the studies. Our final conclusion is that the studies in this review support neither the hypothesis of a faster cognitive decline in DLB, nor in AD.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADL:

-

activities of daily living

- CAMCOG:

-

Cambride cognitive examination

- CDT:

-

clock drawing test

- CERAD:

-

Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease evaluation

- DLB:

-

dementia with Lewy bodies

- DRS:

-

dementia rating scale

- HVLT-R:

-

Hopkins verbal learning test-revised

- MMSE:

-

mini mental state examination

- NEVIP:

-

Newcastle visual perception battery

- NINCDS/ADRDA:

-

National Institute of Neurological and Communication Disorders and Stroke/Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association

- SPECT:

-

ioflupane single-photon emission computed tomotgraphy

- WISC-R:

-

Wechsler intelligence scale for children-revised

References

Aarsland D, Rongve A, Piepenstock Nore S, Skogseth R, Skulstad S, Ehrt U, Hoprekstad D, Ballard C: Frequency and Case Identification of Dementia with Lewy Bodies Using the Revised Consensus Criteria. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008, 26: 445-452. 10.1159/000165917.

McKeith IGI, Dickson DWD, Lowe JJ, Emre MM, O. apos Brien JTJ, Feldman HH, Cummings JJ, Duda JEJ, Lippa CC, Perry EKE, Aarsland DD, Arai HH, Ballard CGC, Boeve BB, Burn DJD, Costa DD, Del Ser T, Dubois BB, Galasko DD, Gauthier SS, Goetz CGC, Gomez-Tortosa EE, Halliday GG, Hansen LAL, Hardy JJ, Iwatsubo TT, Kalaria RNR, Kaufer DD, Kenny RAR, Korczyn AA, et al: Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005, 65: 1863-1872. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1.

Olichney JM, Galasko D, Salmon DP, Hofstetter CR, Hansen LA, Katzman R, Thal LJ: Cognitive decline is faster in Lewy body variant than in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1998, 51: 351-357. 10.1212/WNL.51.2.351.

Oesterhus R, Soennesyn H, Rongve A, Ballard C, Aarsland D, Vossius C: Long-term mortality in a cohort of home-dwelling elderly with mild Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2014, 8: 161-169. 10.1159/000358051.

Rongve A, Vossius C, Nore S, Testad I, Aarsland D: Time until nursing home admission in people with mild dementia: comparison of dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s dementia. Int J Geriat Psychiatry. 2014, 29: 392-398. 10.1002/gps.4015.

Vossius C, Rongve A, Testad I, Wimo A, Aarsland D: The use and costs of formal care in newly diagnosed dementia: a three-year prospective follow-up study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014, 22: 381-388. 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.08.014.

Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Yu L, Boyle PA, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA: Cognitive impairment, decline and fluctuations in older community-dwelling subjects with Lewy bodies. Brain. 2012, 135: 3005-3014. 10.1093/brain/aws234.

Lippa CF, Duda JE, Grossman M, Hurtig HI, Aarsland D, Boeve BF, Brooks DJ, Dickson DW, Dubois B, Emre M, Fahn S, Farmer JM, Galasko D, Galvin JE, Goetz CG, Growdon JH, Gwinn-Hardy KA, Hardy J, Heutink P, Iwatsubo T, Kosaka K, Lee VM-Y, Leverenz JB, Masliah E, McKeith IG, Nussbaum RL, Olanow CW, Ravina BM, Singleton AB, Tanner CM, et al: DLB and PDD boundary issues: diagnosis, treatment, molecular pathology, and biomarkers. Neurology. 2007, 68: 812-819. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000256715.13907.d3.

Janvin CC, Larsen JP, Aarsland D, Hugdahl K: Subtypes of mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: progression to dementia. Mov Disord. 2006, 21: 1343-1349. 10.1002/mds.20974.

Williams-Gray CH, Foltynie T, Brayne CEG, Robbins TW, Barker RA: Evolution of cognitive dysfunction in an incident Parkinson’s disease cohort. Brain. 2007, 130: 1787-1798. 10.1093/brain/awm111.

Clinton LK, Blurton-Jones M, Myczek K, Trojanowski JQ, LaFerla FM: Synergistic Interactions between Abeta, tau, and α-synuclein: acceleration of neuropathology and cognitive decline. J Neurosci. 2010, 30: 7281-7289. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0490-10.2010.

Aarsland D, Zaccai J, Brayne C: A systematic review of prevalence studies of dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2005, 20: 1255-1263. 10.1002/mds.20527.

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR: Introduction to Meta-Analysis. 2011, Wiley, New Jersey

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG: Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003, 327: 557-560. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557.

Kraybill ML, Larson EB, Tsuang DW, Teri L, McCormick WC, Bowen JD, Kukull WA, Leverenz JB, Cherrier MM: Cognitive differences in dementia patients with autopsy-verified AD, Lewy body pathology, or both. Neurology. 2005, 64: 2069-2073. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000165987.89198.65.

Nelson PT, Kryscio RJ, Jicha GA, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, Xu LO, Cooper G, Smith CD, Markesbery WR: Relative preservation of MMSE scores in autopsy-proven dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2009, 73: 1127-1133. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bacf9e.

Ballard C, Patel A, Oyebode F, Wilcock G: Cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia and senile dementia of Lewy body type. Age Ageing. 1996, 25: 209-213. 10.1093/ageing/25.3.209.

Heyman A, Fillenbaum GG, Gearing M, Mirra SS, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Peterson B, Pieper C: Comparison of Lewy body variant of Alzheimer’s disease with pure Alzheimer’s disease: Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease, Part XIX. Neurology. 1999, 52: 1839-1844. 10.1212/WNL.52.9.1839.

Stavitsky K, Brickman AM, Scarmeas N, Torgan RL, Tang M-X, Albert M, Brandt J, Blacker D, Stern Y: The progression of cognition, psychiatric symptoms, and functional abilities in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2006, 63: 1450-1456. 10.1001/archneur.63.10.1450.

McKeith IG, Perry RH, Fairbarin AF, Jabeen S, Perry EK: Operational criteria for senile dementia for Lewy body type (SDLT). Psychol Med. 1992, 22: 911-922. 10.1017/S0033291700038484.

Ballard CG, O’Brien J, Lowery K, Ayre GA, Harrison R, Perry R, Ince P, Neill D, McKeith IG: A prospective study of dementia with Lewy Bodies. Age Ageing. 1998, 27: 631-636. 10.1093/ageing/27.5.631.

Lopez OL, Wisniewski S, Hamilton RL, Becker JT, Kaufer DI, DeKosky ST: Predictors of progression in patients with AD and Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2000, 54: 1774-1779. 10.1212/WNL.54.9.1774.

Stern Y, Jacobs D, Goldman J, Gomez-Tortosa E, Hyman BT, Liu Y, Troncoso J, Marder K, Tang MX, Brandt J, Albert M: An investigation of clinical correlates of Lewy bodies in autopsy-proven Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2001, 58: 460-465.

Ballard C, O’Brien J, Morris CM, Barber R, Swann A, Neill D, McKeith I: The progression of cognitive impairment in dementia with Lewy bodies, vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatri Psychiatry. 2001, 16: 499-503. 10.1002/gps.381.

Helmes E, Bowler J, Merskey H, Munoz DG, Hachinski VC: Rates of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2003, 15: 67-71. 10.1159/000067969.

Johnson DK, Morris JC, Galvin JE: Verbal and visuospatial deficits in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2005, 65: 1232-1238. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000180964.60708.c2.

Williams MM, Xiong C, Morris JC, Galvin JE: Survival and mortality differences between dementia with Lewy bodies vs Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006, 67: 1935-1941. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000247041.63081.98.

Hamilton JM, Salmon DP, Galasko D, Raman R, Emond J, Hansen LA, Masliah E, Thal LJ: Visuospatial deficits predict rate of cognitive decline in autopsy-verified dementia with Lewy bodies. Neuropsychology. 2008, 22: 729-737. 10.1037/a0012949.

Hanyu H, Sato T, Hiraro K, Kanetaka H, Sakurai H, Iwamoto T: Differences in clinical course between dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2009, 16: 212-217. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02388.x.

Wood JS, Watson R, Firbank MJ, Mosimann UP, Barber R, Blamire AM, O’Brien JT: Longitudinal testing of visual perception in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriat Psychiatry. 2013, 28: 567-572. 10.1002/gps.3860.

Walker Z, McKeith I, Rodda J, Qassem T, Tatsch K, Booij J, Darcourt J, O’Brien J: Comparison of cognitive decline between dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2012, 2: e000380-10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000380.

Metzler-Baddeley C: A review of cognitive impairments in dementia with Lewy bodies relative to Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease with dementia. Cortex. 2007, 43: 583-600. 10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70489-1.

Brown J, Pengas G, Dawson K, Brown LA, Clatworthy P: Self administered cognitive screening test (TYM) for detection of Alzheimer’s disease: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2009, 338: b2030-10.1136/bmj.b2030.

Yoshizawa H, Vonsattel JPG, Honig LS: Early neuropsychological discriminants for Lewy body disease: an autopsy series. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2013, 84: 1326-1330. 10.1136/jnnp-2012-304381.

Galasko DR, Gould RL, Abramson IS, Salmon DP: Measuring cognitive change in a cohort of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Stat Med. 2000, 19: 1421-1432. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(20000615/30)19:11/12<1421::AID-SIM434>3.0.CO;2-P.

Clark CM, Sheppard L, Fillenbaum GG, Galasko D, Morris JC, Koss E, Mohs R, Heyman A: Variability in annual Mini-Mental State Examination score in patients with probable Alzheimer disease: a clinical perspective of data from the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease. Arch Neurol. 1999, 56: 857-862. 10.1001/archneur.56.7.857.

Parkkinen L, Pirttilä T, Alafuzoff I: Applicability of current staging/categorization of α-synuclein pathology and their clinical relevance. Acta Neuropathol. 2008, 115: 399-407. 10.1007/s00401-008-0346-6.

Alafuzoff I, Ince PG, Arzberger T, Al-Sarraj S, Bell J, Bodi I, Bogdanovic N, Bugiani O, Ferrer I, Gelpi E, Gentleman S, Giaccone G, Ironside JW, Kavantzas N, King A, Korkolopoulou P, Kovács GG, Meyronet D, Monoranu C, Parchi P, Parkkinen L, Patsouris E, Roggendorf W, Rozemuller A, Stadelmann-Nessler C, Streichenberger N, Thal DR, Kretzschmar H: Staging/typing of Lewy body related α-synuclein pathology: a study of the BrainNet Europe Consortium. Acta Neuropathol. 2009, 117: 635-652. 10.1007/s00401-009-0523-2.

Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA: Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007, 69: 2197-2204. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271090.28148.24.

McCann H, Stevens CH, Cartwright H, Halliday GM: α-Synucleinopathy phenotypes. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014, 20: 62-67. 10.1016/S1353-8020(13)70017-8.

Acknowledgement

We want to thank the librarian in Helse Fonna, Tonje Velde, for helping us with the systematic literature search.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Dag Aarsland has received research support and honoraria from H Lundbeck, Novartis Pharmaceuticals and GE Health. None of the other authors have competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MHB and LJC have made the conception and design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafted the manuscript. AR, MJH, CJ, KB and DA have contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. KB also performed the meta-analysis. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Breitve, M.H., Chwiszczuk, L.J., Hynninen, M.J. et al. A systematic review of cognitive decline in dementia with Lewy bodies versus Alzheimer’s disease. Alz Res Therapy 6, 53 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-014-0053-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-014-0053-6