Abstract

Background

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is increasingly recognized as a significant health issue. Emerging research has focused on the role of the gut microbiota in NAFLD, emphasizing the gut-liver axis. This study aimed to identify key research trends and guide future investigations in this evolving area.

Methods

This bibliometric study utilized Scopus to analyze global research on the link between the gut microbiota and NAFLD. The method involved a search strategy focusing on relevant keywords in article titles, refined by including only peer-reviewed journal articles. The data analysis included bibliometric indicators such as publication counts and trends, which were visualized using VOSviewer software version 1.6.20 for network and co-occurrence analysis, highlighting key research clusters and emerging topics.

Results

Among the 479 publications on the gut microbiota and NAFLD, the majority were original articles (n = 338; 70.56%), followed by reviews (n = 119; 24.84%). The annual publication count increased from 1 in 2010 to 118 in 2022, with a significant growth phase starting in 2017 (R2 = 0.9025, p < 0.001). The research was globally distributed and dominated by China (n = 231; 48.23%) and the United States (n = 90; 18.79%). The University of California, San Diego, led institutional contributions (n = 18; 3.76%). Funding was prominent, with 62.8% of the articles supported, especially by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (n = 118; 24.63%). The average citation count was 43.23, with an h-index of 70 and a citation range of 0 to 1058 per article. Research hotspots shifted their focus post-2020 toward the impact of high-fat diets on NAFLD incidence.

Conclusions

This study has effectively mapped the growing body of research on the gut microbiota-NAFLD relationship, revealing a significant increase in publications since 2017. There is significant interest in gut microbiota and NAFLD research, mainly led by China and the United States, with diverse areas of focus. Recently, the field has moved toward exploring the interconnections among diet, lifestyle, and the gut-liver axis. We hypothesize that with advanced technologies, new opportunities for personalized medicine and a holistic understanding of NAFLD will emerge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In recent decades, a significant number of health complications, including cardiovascular disorders, diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome, have emerged as threats to public health [1,2,3]. Among these threats, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has also been recognized as a public health problem [4, 5]. The term NAFLD incorporates a range of liver disorders that collectively share the common feature of excess fat in the absence of significant alcohol consumption (from simple steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis) [4, 6]. NAFLD affects approximately 47 individuals out of every 1,000 individuals or more than 38% of the population and is associated with significantly increased all-cause mortality [7, 8].

Different risk factors are hypothesized to influence the development and progression of NAFLD. An accepted hypothesis is that insulin resistance, obesity, the production of reactive oxygen species, and genetics play a role in the pathogenesis of NAFLD. Specifically, insulin resistance contributes to fat accumulation in liver cells through increased triglycerides and fatty acids, along with reduced excretion and carbohydrate-induced fatty acid synthesis, leading to steatosis. Obesity is believed to aggravate liver damage by releasing inflammatory substances such as leptin from fat tissue, leading to liver cell destruction [6, 9, 10].

Moreover, evidence suggests that irregularities in the composition of intestinal microorganisms are additional risk factors for specific diseases [11,12,13,14,15,16]. The gut microbiota is known for its substantial impact on various bodily functions, including host metabolism, immune function, and even neurobehavioral traits [17,18,19,20]. The connection between the gut and the liver is commonly referred to as the “gut-liver axis” [12]. An alternative proposed mechanism involves dysfunction of the intestinal barrier, permitting gut bacterial metabolites to enter the liver, thereby increasing inflammation, oxidative stress, and lipid accumulation. This cascade expedites liver injury and fibrosis and influences the progression of NAFLD [20,21,22].

The discovery of this relationship and the subsequent growing interest in this relationship have led to a recognizable increase in the number of relevant scientific publications [23]. However, the sheer number, complexity of contexts, and diversity of publications make it challenging to synthesize and understand overarching trends and contributions in this field. This is where bibliometric analysis comes in [24, 25]. By assessing publication output, identifying research themes, and mapping collaborative networks, bibliometric analyses can help in identifying patterns and trends of publications in addition to quantifying contributions to the field and identifying future research directions.

Generally, systematic reviews, scoping reviews, and bibliometric analyses might appear similar due to their overlapping elements; however, they differ significantly. Bibliometric analyses are designed to perform a survey of literature on a specific subject. Unlike systematic reviews, which provide a targeted and specific assessment, bibliometric analyses offer a more holistic view [26]. While systematic reviews typically use a limited set of publications to address a precise research question, bibliometric analyses include a broader range of literature [26, 27]. Scoping reviews, on the other hand, focus on charting the scope and nature of the existing evidence to assist further in-depth studies [28]. In contrast, bibliometric analyses expand beyond this by providing publication frequency, authorship patterns, and citation analysis. These data enable an understanding of trends and patterns within a research area, making bibliometric analyses invaluable for identifying research gaps [29, 30].

Numerous studies have examined research trends within the realms of microbiota and the liver, encompassing a broad range of diseases [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Additionally, bibliometric analyses have investigated the gut microbiota independently [25, 40,41,42,43], as well as the incidence of NAFLD [44,45,46,47], with a notable absence of integration between these subjects. Therefore, this study intends to fill this gap by conducting a bibliometric analysis that combines both. The objective is to uncover trends and patterns in the research field, examine global and institutional collaborations, and determine key funding agencies. This study will also highlight noteworthy journals and articles in this area, in addition to providing future directions.

Methods

Study design

A descriptive, retrospective, cross-sectional, and bibliometric study design was used in this study.

Database

Due to its comprehensive coverage and advanced search capabilities, the Scopus database was selected as the sole source for the evaluation of the global scientific output of the gut microbiota and its connection to NAFLD. In bibliometric research, utilizing a single database is customary because combining data from multiple sources can complicate bibliometric analyses and literature mapping. Additionally, gray literature, which encompasses non-peer-reviewed materials, cannot be effectively integrated into data retrieved from multiple databases [48,49,50].

The decision to use the SciVerse Scopus database for this study stemmed from several factors. First, Scopus boasts a far greater volume and diversity of indexed publications than its counterparts, PubMed and Web of Science. In fact, Scopus’s journal index nearly surpasses the combined index of PubMed and Web of Science [51,52,53,54,55]. Second, Scopus encompasses all the articles listed in PubMed, ensuring complete coverage of the PubMed literature within Scopus. As a result, Scopus is considered a comprehensive database that includes both PubMed and Web of Science publications [51,52,53,54,55]. Furthermore, Scopus’s interdisciplinary nature, spanning science, technology, medicine, social science, and the arts and humanities, aligns with the diverse range of research on the gut microbiota and NAFLD. Additionally, the advanced search functionality of Scopus, which employs various Boolean operators, facilitates the creation of sophisticated and comprehensive search queries. Finally, Scopus empowers researchers to seamlessly export and analyze retrieved data, enabling mapping and statistical analyses. Considering the rapid update cycle of the database, literature retrieval was conducted on a single day, November 22, 2023. Consequently, the study’s publication period encompassed the entire preceding year, up to December 31, 2022.

Search strategies

Utilizing the “Advanced search” functionality of the Scopus online database, we used relevant keywords to identify literature pertaining to the gut microbiota and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The search strategy involved utilizing synonyms for both the gut microbiota and NAFLD as follows:

Step 1

First, we gathered terms related to the gut microbiota from prior research on the topic [24, 25, 41, 56,57,58,59,60] and medical subject headings (MeSH) from PubMed. These selected terms were subsequently included in the “Article Title” field of the Scopus search engine to accomplish the goals of our study: “Colonic flora” OR “Colonic microflora” OR “Colonic microbiome” OR “Colonic microbiota” OR “Digestive flora” OR “Digestive microflora” OR “Digestive microbiome” OR “Digestive microbiota” OR “Enteric bacteria” OR “Enteric flora” OR “Enteric microflora” OR “Enteric microbiome” OR “Enteric microbiota” OR “Fecal flora” OR “Fecal microflora” OR “Fecal microbiome” OR “Fecal microbiota” OR “Gastric flora” OR “Gastric microflora” OR “Gastric microbiome” OR “Gastric microbiota” OR “Gastrointestinal flora” OR “Gastrointestinal microflora” OR “Gastrointestinal microbiome” OR “Gastrointestinal microbiota” OR “Gastrointestinal microbial community” OR “Gastrointestinal microflora” OR “Gut flora” OR “Gut microflora” OR “Gut microbiome” OR “Gut microbiota” OR “Intestinal flora” OR “Intestinal microflora” OR “Intestinal microbiome” OR “Intestinal microbiota”.

Step 2

Following the initial step, we further refined our search by limiting the identified publications to those that included the terms “nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and associated terms” in their titles. The terms associated with NAFLD were sourced from the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) in PubMed and subsequently entered into the Scopus database for this purpose. The following ‘terms’ were entered as ‘Article Title’: “NAFLD” OR “Non alcoholic Fatty Liver” OR “Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver” OR “Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver” OR “Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis” OR “Non alcoholic Steatohepatitis” OR “Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis”. In 2020, a new term was introduced for fatty liver disease: metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD). This name change reflects the understanding that this condition is linked to broader problems with metabolism throughout the body [61]. Our research focused on the well-defined term “NAFLD”, which was the established standard at the time of data collection. While we acknowledge the existence of the related term “MAFLD”, we opted to focus on NAFLD due to its wider recognition and established trends in research. Our decision reflects our specific interest in NAFLD itself rather than encompassing broader related terminology.

Step 3

The research limits its scope to peer-reviewed scientific journal articles, excluding books, book chapters, retracted articles, and errata.

Validation of the search strategy

Two biomedical science colleagues, well versed in bibliometrics, were enlisted to validate the search strategy. This validation involved two distinct methods. Initially, the colleagues were tasked with ensuring the absence of false-positive articles by scrutinizing 47 randomly selected articles from the retrieved document (articles ranked 10, 20, 30, etc., based on citations). Valuable feedback from volunteers contributed to refining the research strategy. Subsequently, the experts were directed to compare the publication counts of the top 20 active authors with the actual number of articles for each scholar, examining their respective Scopus profiles. To ascertain the significance and correlation coefficient, the results from both methods were subjected to correlation testing. The results of the correlation test revealed a strong correlation coefficient (r = 0.987), and the statistical significance (p < 0.001) underscored the accuracy of the search query. This dual-method approach aimed to verify the absence of false-negative outcomes, drawing inspiration from previously published bibliometric studies [49, 62]. Notably, keywords were employed in the title search rather than in the title/abstract search, enhancing the reliability of the approach. Consequently, the title search emerged as a dependable method with minimal false-positive documents, unlike the title/abstract search [29, 48, 50], which yielded numerous false positives with a focus not specifically on NAFLD and the gut microbiota.

Bibliometric analysis

Bibliometric indicators, including the total number of publications, publication years, types of publications, top ten funding agencies, top ten countries, top ten institutions, top ten journals, and the top ten most cited articles, were gathered using an Excel spreadsheet.

Visualization analysis

The intricate connections between terms and collaborating countries were visualized using VOSviewer software version 1.6.20 (Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands). Network maps were constructed to depict the interplay of terms extracted from article titles or abstracts and the collaborative ties between countries [63,64,65]. A co-occurrence analysis was simultaneously performed to segregate terms into distinct clusters, which were further enhanced by color coding based on their temporal distribution. To assess the emergence of new topics and identify evolving trends, the average publication year was calculated.

Results

General description of the retrieved publications

This study included a total of 479 publications. Among them, articles constituted the majority, with 338 publications, composing 70.56% of the overall records and establishing them as the most prevalent literary form. A total of 119 publications were identified, accounting for 24.84% of the total. The remaining five types of publications, namely, documents such as letters, notes, editorials, minutes of meetings, and short surveys, totalled 22, representing 4.59% of the overall corpus.

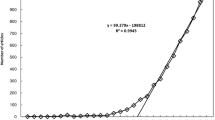

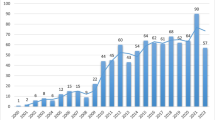

Growth and productivity trends

The number of publications on the gut microbiota and NAFLD increased each year during the study period. The number of publications ranged from 1 in 2010 to 118 in 2022, as shown in Fig. 1. Two distinct stages of growth were observed: the first stage, from 2010 to 2016, had a slow rate of publication production, while the second stage, from 2017 to 2022, had a much faster rate of publication progress. Statistical analysis using linear regression confirmed this observation and indicated a strong positive correlation (R2 = 0.9025, p < 0.001) between the annual publication count and the corresponding publication year.

Top active countries

Between 2010 and 2022, researchers conducted studies on the gut microbiota and NAFLD in a diverse array of 47 countries. In particular, the top ten countries represented a substantial 82.67% of all relevant research, as outlined in Table 1. China was the primary contributor, with 231 articles (48.23%), followed by the United States (90 articles; 18.79%), France and Italy, each contributing 22 articles (4.59%). Furthermore, the U.S. and China displayed significant involvement in international collaboration, leading to publications featuring scholars from various nations. To visually represent these global research networks, Fig. 2 illustrates a network mapping chart depicting international collaborations in studies on the gut microbiota and NAFLD among the prominent participating countries from 2010 to 2022.

Visualization of international research collaboration networks related to the gut microbiota and NAFLD: 2010–2022. This collaborative network map showcases the interactions among leading countries engaged in research on the gut microbiota and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease from 2010 to 2022. The map is based on a threshold of at least 5 publications per country, with 21 out of the 47 active countries meeting this criterion. The size of each node on the map corresponds to the number of publications from that respective country. The map was generated using VOSviewer software version 1.6.20

Top active institutions

Table 2 provides a comprehensive list of the ten most productive institutes in the field of NAFLD and its correlation with the gut microbiota covering the period from 2010 to 2022. Together, these leading institutions contributed to 20.25% (n = 97) of the total articles published on the subject. The University of California, San Diego, emerged as the leading contributor globally, producing 18 publications and generating 3.76% of the overall publications. Similarly, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine in China secured the second position with 17 publications (3.55%), followed by the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China with 15 publications (3.13%) and the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine with 10 publications (2.09%) (Table 2).

Top ten funding agencies

A significant portion of the articles recovered, 62.8% of which had 301 publications and received financial support. Table 3 provides information on the top 10 funding agencies associated with NAFLD and its correlation with the gut microbiota from 2010 to 2022. These leading 10 agencies collectively contributed to 39.45% (n = 189) of the total published articles. In particular, the National Natural Science Foundation of China in China emerged as the most active funding agency in the field, supporting 24.63% (n = 118) of the articles. The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases in the USA (n = 23; 4.80%), the National Institutes of Health in the USA (n = 16; 3.34%) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (n = 16; 3.34%) were followed closely.

Top ten most active journals

According to the data presented in Table 4, the collective contribution of the top 10 journals/source titles constitutes approximately 24.21% of the general publications pertaining to research on NAFLD and its association with the gut microbiota. The International Journal of Molecular Sciences, which boasted an impact factor of 5.6 in 2023, exhibited the highest publication count, totaling 16 publications. Subsequently, Nutrients, with an impact factor of 5.9 in 2023, closely followed 14 publications, while Frontiers in Microbiology, featuring an impact factor of 5.2 in 2023, recorded 13 publications.

Analysis of citations

By conducting a citation analysis, it was determined that the articles garnered an average of 43.23 citations, resulting in an h-index of 70 and a cumulative total of 20,705 citations. Among these articles, 122 did not receive any citations, while 124 obtained more than 100 citations. The citation count for these articles ranged from 0 to 1058. Table 5 shows the top ten publications on NAFLD and its correlation with diet, for a total of 5,637 citations. The citation range for these publications ranges from 387 to 882 [12, 14, 15, 66,67,68,69,70,71,72].

Hot spots related to NAFLD and gut microbiota research

Figure 3 illustrates the main focal points concerning NAFLD and its connection to the gut microbiota from 2010 to 2022. Using VOSviewer analysis of the 479 retrieved documents, the titles and abstracts were searched for terms, resulting in the creation of a map featuring 142 terms. These terms were drawn from a total of 9,440 terms in the field and organized into three groups, each with a minimum of 20 appearances per term. The noteworthy terms on the map encompass (a) the impact of high-fat diets on the gut microbiome and its association with the development of NAFLD (red cluster); (b) the role of the gut microbiota in obesity and the development of NAFLD (blue cluster); and (c) the involvement of the gut–liver axis in the dysbiosis of the gut microbiome linked to NAFLD (green cluster).

Network visualization map of terms in the title/abstract of publications related to the gut microbiota and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease from 2010 to 2022. The map was created using VOSviewer software version 1.6.20, with a minimum-term occurrence threshold of 20. Of the total 9,440 terms in this field, 142 terms reached this threshold and were divided into three clusters, each represented by a different color. The size of each node in the map indicates the frequency of a term’s usage across publications. The map was generated using VOSviewer software version 1.6.20

Future research direction analysis

In Fig. 4, VOSviewer assigned distinct colors to each term based on its average frequency in all retrieved publications. The color scheme signifies the chronological distribution of term appearances, with blue indicating earlier occurrences and yellow representing more recent occurrences. Prior to 2020, the primary focus in this field revolved around ‘investigating the role of the gut microbiota in obesity and the development of NAFLD’ and ‘investigating the involvement of the gut–liver axis in the dysbiosis of the gut microbiota linked to NAFLD’. However, the term “impact of high-fat diets on the gut microbiome and its association with NAFLD development” emerged more recently after 2020, indicating the current trajectory of research interest.

Visualization of Term Analysis of the Gut Microbiota and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Publications (2010–2022). This network visualization map illustrates the analysis of terms found in the titles and abstracts of publications related to the gut microbiota and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. The map shows the frequency of term appearances, with earlier occurrences represented in blue and later occurrences in yellow. The map was generated using VOSviewer software version 1.6.20

Discussion

This study represents the first in-depth bibliometric analysis focusing on global research trends in the association between the gut microbiota and NAFLD. It encompasses a variety of dimensions, such as types of documents, annual publication trends, contributions from top countries and institutions, leading journals with their impact factors, most cited articles, and a co-occurrence analysis of frequently used terms to pinpoint the most researched topics within this field.

The study’s results reveal a significant increase in research output, especially in the past decade. This escalation is evident in the exponential rise in publications, particularly from 2017 onward, indicating heightened interest and focus in the field. This pattern of intensification is likely a product of the expanding interest in the relationship between the gut microbiota and NAFLD, a relationship that is now acknowledged as essential in the holistic understanding of this condition [11,12,13,14, 66, 70].

The number of publications initially experienced a modest yet steady rise in output. Although the volume was limited, these publications played a significant role in garnering interest in the topic. For instance, an article by Jiang, W. et al. described the relationship between the gut microbiota composition and the development of NAFLD. Dysbiosis contributes to inflammation and impaired mucosal immune function [12, 15, 73]. Another study by Leung, C. et al. explored the link between dietary fats and the gut microbiota, illustrating the link between poor diet and consequent obesity, hepatic steatosis and NAFLD. Moreover, further studies have explored various aspects of NAFLD and the gut microbiota, including Abu-Shanab, A. et al.‘s research on identifying microbial metabolites as potential early indicators of NAFLD pathogenesis and Alkhouri N. and team’s work on pediatric NAFLD, which led to the development of novel histological scores to enhance the understanding and treatment of NAFLD in children [12, 15, 73].

In the second phase, from 2017 onward, there was more significant growth in research output. driven by enhanced microbiological techniques and a deeper understanding of the gut–liver axis. Studies have demonstrated that gut microbiota dysbiosis is closely linked to NAFLD in individuals with metabolic diseases such as obesity and type 2 diabetes. This period saw significant advances in identifying specific microbiome signatures that distinguish healthy individuals from those with NAFLD, despite challenges in differentiating these signatures from underlying metabolic disorders [14, 16]. Notably, pediatric NAFLD has also garnered attention, as metagenomics and metabolomics have revealed distinct microbial and compound alterations [67]. A major achievement was the development of a gut microbiota-derived metagenomic signature for predicting advanced fibrosis in NAFLD patients, revealing a noninvasive method for detecting advanced stages of the disease with high accuracy [70].

The geographical distribution of publications reveals a significant concentration of research activity in specific countries. China leads, followed by the United States, France, and Italy. This distribution highlights not only the global nature of NAFLD research but also the varying levels of interest and investment in different regions. China’s lead in publication output could be linked to its ongoing efforts to bolster scientific research, in addition to its widely known focus on traditional and integrative medicine approaches for metabolic diseases [74,75,76,77]. One such effort is China’s substantial investment in establishing state-of-the-art laboratories and research institutes to attract scientists and increase its research output [78, 79]. Another way that China is driving the observed increase in research output is establishing funding agencies.

Funding agencies have been demonstrated to play a pivotal role in shaping the focus and scope of scientific research [80]. An illustrative case of this influence, potentially contributing to China’s excellence in researching the gut microbiota and NAFLD, is the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC). By serving as a major sponsor for both fundamental and applied scientific research, the NSFC has significantly improved China’s research outcomes. This is particularly evident in the substantial surge in publications following the establishment of a specialized NSFC dedicated to investigating the gut-liver axis [81, 82]. Nevertheless, the United States is not far behind; its substantial contributions are likely a consequence of its prominence in biomedical research and the availability of funding for such studies [83, 84]. The role of funding agencies is also noteworthy in the United States. Entities such as the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have been instrumental in advancing overall research in the United States, specifically concerning the gut microbiota [85]. This is exemplified in the NIH’s Human Microbiome Project [86] and various other projects [85].

Research on the gut microbiota and NAFLD has historically made meaningful contributions to our understanding of this relationship. In addition to receiving a high number of citations and demonstrating high h-index values, this research has been concentrated in high-impact journals such as the International Journal of Molecular Sciences, Nutrients, and Frontiers in Microbiology. These metrics, along with acceptance in high-impact journals and subsequent publications, underscore the significance of these works and their recognition in the field [87].

The term co-occurrence analysis revealed the varied nature of research in this area over the past decades. Initially, interest focused on understanding the relationship between the gut microbiome and liver health, as highlighted in topics such as “investigation into the role of gut microbiota in obesity and the development of NAFLD” and “the involvement of the gut-liver axis in gut microbiome dysbiosis linked to NAFLD” [88]. More recently, in parallel with the global rise in dietary-related health issues and the need to understand how lifestyle influences disease etiology, research has shifted its focus to understanding the impact of high-fat diets on the gut microbiota and their link to NAFLD development [89,90,91,92,93].

Future directions

In the future, research on the gut microbiota and NAFLD may focus more on a deeper understanding of how diet, gut bacteria, and liver health are connected. This could involve studying how specific foods affect the microbiota and, in turn, NAFLD. Researchers should also focus on how lifestyle factors such as exercise and daily routines influence the gut-liver axis. Advanced genetic and metabolic technology should open up new avenues to diagnose or treat NAFLD by studying how gut microbes interact with human cells.

Another promising direction for managing NAFLD is personalized medicine. Given the variability in gut microbiota composition among individuals, personalized dietary or probiotic interventions based on one’s specific microbiome profile could be explored. This approach would require a concerted effort in large-scale data collection and analysis, integrating microbiome data with genetic, metabolic, and clinical information. Furthermore, the interaction between the gut microbiota and other organ systems beyond the liver is likely to become a significant area of study, offering an understanding of the systemic nature of NAFLD and its links with other diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes.

Limitations

Several limitations of our study should be acknowledged. First, our reliance on Scopus as the sole data source, while advantageous due to its extensive database of peer-reviewed literature, may have led to the exclusion of relevant studies not indexed in this platform. While Scopus’s comprehensive coverage mitigates this limitation to some extent, there is still a possibility of missing pertinent literature from other databases. Second, the methodology focused on identifying relevant terms in the titles and abstracts of publications and missing studies that discussed the gut microbiota-NAFLD relationship in different parts of the literature. Third, determining the geographic origin of research based on affiliation information may not always be accurate. Fourth, the analysis focused specifically on the connection between the gut microbiota and NAFLD incidence, excluding other potential factors, such as genetics, lifestyle, or the environment, that could also be important in NAFLD development. Fifth, we considered only English-language publications. Sixth, we prioritized established terms such as NAFLD in our literature search to capture the research trends reflecting our specific interest in NAFLD itself rather than encompassing broader related terminology. Although this approach yielded a robust collection of existing studies, some of the latest publications that encompass both NAFLD and the newer term MAFLD might have been missed. Finally, our study was primarily descriptive, aiming to identify trends and patterns in the literature rather than evaluating the quality, impact, or relevance of individual studies in the broader context of NAFLD research.

Conclusions

This study mapped the publication output of gut microbiota and NAFLD research. There has been significant growth in publications since 2017. Key findings include the importance of gut microbiota imbalances in NAFLD and the impact of diet. The research is global, with China and the U.S. making major contributions. In the future, research should explore diet, lifestyle, and the gut-liver connection. Advanced technology should lead to breakthroughs in personalized medicine and a deeper understanding of the wider effects of NAFLD.

Data availability

All the information produced or examined in this research is contained within this published article. Additional datasets utilized in the course of this study can be obtained from the corresponding authors.

Abbreviations

- IF:

-

Impact factor

- MeSH:

-

Medical Subject Headings

- NAFLD:

-

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NIH:

-

National Institutes of Health

- NSFC:

-

National Natural Science Foundation of China

- p:

-

Statistically significant

- R2 :

-

Coefficient of determination in linear regression

- r:

-

Correlation coefficient

- Scopus:

-

SciVerse Scopus database

- USA:

-

United States of America

References

Saklayen MG. The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20.

Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015., et al. Lancet. 2016;388:1659–724.

World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. Accessed 13 Dec 2023.

Pouwels S, Sakran N, Graham Y, Leal A, Pintar T, Yang W, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a review of pathophysiology, clinical management and effects of weight loss. BMC Endocr Disord. 2022;22:63.

Le MH, Yeo YH, Zou B, Barnet S, Henry L, Cheung R, et al. Forecasted 2040 global prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease using hierarchical bayesian approach. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2022;28:841–50.

Basaranoglu M, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: clinical features and Pathogenesis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2006;2:282–91.

Teng ML, Ng CH, Huang DQ, Chan KE, Tan DJ, Lim WH, et al. Global incidence and prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2023;29 Suppl:S32–42.

Konyn P, Ahmed A, Kim D. Causes and risk profiles of mortality among individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2022;29 Suppl:S43–57.

Brunt EM, Tiniakos DG. Histopathology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5286–96.

Del Campo JA, Gallego-Durán R, Gallego P, Grande L. Genetic and epigenetic regulation in nonalcoholic fatty liver Disease (NAFLD). Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:911.

JASIRWAN COM, LESMANA CRA, HASAN I, SULAIMAN AS, GANI RA. The role of gut microbiota in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: pathways of mechanisms. Biosci Microbiota Food Health. 2019;38:81–8.

Leung C, Rivera L, Furness JB, Angus PW. The role of the gut microbiota in NAFLD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:412–25.

Hrncir T, Hrncirova L, Kverka M, Hromadka R, Machova V, Trckova E, et al. Gut microbiota and NAFLD: pathogenetic mechanisms, Microbiota signatures, and therapeutic interventions. Microorganisms. 2021;9:957.

Aron-Wisnewsky J, Vigliotti C, Witjes J, Le P, Holleboom AG, Verheij J, et al. Gut microbiota and human NAFLD: disentangling microbial signatures from metabolic disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:279–97.

Abu-Shanab A, Quigley EMM. The role of the gut microbiota in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:691–701.

Shen F, Zheng R-D, Sun X-Q, Ding W-J, Wang X-Y, Fan J-G. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2017;16:375–81.

Verdú EF, Bercik P, Verma-Gandhu M, Huang X-X, Blennerhassett P, Jackson W, et al. Specific probiotic therapy attenuates antibiotic induced visceral hypersensitivity in mice. Gut. 2006;55:182–90.

Lach G, Fülling C, Bastiaanssen TFS, Fouhy F, Donovan ANO, Ventura-Silva AP, et al. Enduring neurobehavioral effects induced by microbiota depletion during the adolescent period. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:1–16.

Lambring CB, Siraj S, Patel K, Sankpal UT, Mathew S, Basha R. Impact of the Microbiome on the Immune System. Crit Rev Immunol. 2019;39:313–28.

Martin AM, Sun EW, Rogers GB, Keating DJ. The influence of the gut microbiome on host metabolism through the regulation of gut hormone release. Front Physiol. 2019;10.

Debnath N, Kumar R, Kumar A, Mehta PK, Yadav AK. Gut-microbiota derived bioactive metabolites and their functions in host physiology. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev. 2021;37:105–53.

Carding S, Verbeke K, Vipond DT, Corfe BM, Owen LJ. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in disease. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2015;26. https://doi.org/10.3402/mehd.v26.26191.

Su X, Chen S, Liu J, Feng Y, Han E, Hao X et al. Composition of gut microbiota and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2023;:e13646.

Zyoud SH, Shakhshir M, Abushanab AS, Koni A, Shahwan M, Jairoun AA, et al. Gut microbiota and autism spectrum disorders: where do we stand? Gut Pathogens. 2023;15:50.

Zyoud SH, Smale S, Waring WS, Sweileh WM, Al-Jabi SW. Global research trends in microbiome-gut-brain axis during 2009–2018: a bibliometric and visualized study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:158.

Møller AM, Myles PS. What makes a good systematic review and meta-analysis? Br J Anaesth. 2016;117:428–30.

Donthu N, Kumar S, Mukherjee D, Pandey N, Lim WM. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: an overview and guidelines. J Bus Res. 2021;133:285–96.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69.

Zyoud SH, Shakhshir M, Abushanab AS, Koni A, Shahwan M, Jairoun AA, et al. Bibliometric mapping of the landscape and structure of nutrition and depression research: visualization analysis. J Health Popul Nutr. 2023;42:33.

Ellegaard O, Wallin JA. The bibliometric analysis of scholarly production: how great is the impact? Scientometrics. 2015;105:1809–31.

Chen Z, Ding C, Gu Y, He Y, Chen B, Zheng S, et al. Association between gut microbiota and hepatocellular carcinoma from 2011 to 2022: bibliometric analysis and global trends. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1120515.

Liao Y, Wang L, Liu F, Zhou Y, Lin X, Zhao Z, et al. Emerging trends and hotspots in metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) research from 2012 to 2021: a bibliometric analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1078149.

Shibo C, Sili W, Yanfang Q, Shuxiao G, Susu L, Xinlou C et al. Emerging trends and hotspots in the links between the bile acids and NAFLD from 2002 to 2022: a bibliometric analysis. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2023;:e460.

Li Y, Zhou Y, Wang L, Lin X, Mao M, Yin S, et al. Emerging trends and hotspots in the links between the gut microbiota and MAFLD from 2002 to 2021: a bibliometric analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:990953.

Yang S, Yu D, Liu J, Qiao Y, Gu S, Yang R, et al. Global publication trends and research hotspots of the gut-liver axis in NAFLD: a bibliometric analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1121540.

Wang Q, Chen C-X, Zuo S, Cao K, Li H-Y. Global research trends on the links between intestinal microbiota and liver diseases: a bibliometric analysis. Am J Transl Res. 2023;15:5364–72.

Dai J-J, Zhang Y-F, Zhang Z-H. Global trends and hotspots of treatment for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a bibliometric and visualization analysis (2010–2023). World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:5339–60.

Pezzino S, Sofia M, Mazzone C, Castorina S, Puleo S, Barchitta M et al. Gut microbiome in the progression of NAFLD, NASH and Cirrhosis, and its connection with Biotics: a bibliometric study using dimensions Scientific Research Database. Biology (Basel). 2023;12.

Zhang D, Liu B-W, Liang X-Q, Liu F-Q. Immunological factors in cirrhosis diseases from a bibliometric point of view. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:3899–921.

Ejtahed H-S, Tabatabaei-Malazy O, Soroush A-R, Hasani-Ranjbar S, Siadat S-D, Raes J, et al. Worldwide trends in scientific publications on association of gut microbiota with obesity. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2019;22:65–71.

Zhu X, Hu J, Deng S, Tan Y, Qiu C, Zhang M et al. Bibliometric and Visual Analysis of Research on the Links between the Gut Microbiota and Depression from 1999 to 2019. Front Psychiatry. 2021;11.

Yuan X, Chang C, Chen X, Li K. Emerging trends and focus of human gastrointestinal microbiome research from 2010–2021: a visualized study. J Transl Med. 2021;19:327.

Colombino E, Prieto-Botella D, Capucchio MT. Gut Health in Veterinary Medicine: a bibliometric analysis of the literature. Anim (Basel). 2021;11:1997.

Vaishya R, Gupta BM, Kappi MM, Misra A, Kuchay MS, Vaish A. Research on non-alcoholic fatty liver Disease from Indian Subcontinent: a bibliometric analysis of publications during 2001–2022. J Clin Experimental Hepatol. 2024;14:101271.

Li Z, Cao S, Zhao S, Kang N. A bibliometric analysis and visualization of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease from 2012 to 2021. Clin Exp Med. 2023;23:1961–71.

Zhang T-S, Qin H-L, Wang T, Li H-T, Li H, Xia S-H, et al. Bibliometric analysis of top 100 cited articles in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease research. World J Hepatol. 2016;8:1478–88.

Zhang T, Qin H, Wang T, Li H, Li H, Xia S, et al. Global publication trends and research hotspots of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a bibliometric analysis and systematic review. SpringerPlus. 2015;4:776.

Sweileh WM. Substandard and falsified medical products: bibliometric analysis and mapping of scientific research. Globalization Health. 2021;17:114.

Sweileh WM. Analysis and mapping of global research publications on shift work (2012–2021). J Occup Med Toxicol. 2022;17:22.

Sweileh WM. Global research activity on mathematical modeling of transmission and control of 23 selected infectious disease outbreak. Globalization Health. 2022;18:4.

AlRyalat SAS, Malkawi LW, Momani SM. Comparing Bibliometric Analysis using PubMed, Scopus, and web of Science Databases. J Vis Exp. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3791/58494.

Bakkalbasi N, Bauer K, Glover J, Wang L. Three options for citation tracking: Google Scholar, Scopus and web of Science. Biomedical Digit Libr. 2006;3:7.

Falagas ME, Pitsouni EI, Malietzis GA, Pappas G. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, web of Science, and Google Scholar: strengths and weaknesses. FASEB J. 2008;22:338–42.

Kulkarni AV, Aziz B, Shams I, Busse JW. Comparisons of citations in web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar for articles published in general medical journals. JAMA. 2009;302:1092–6.

Sember M, Utrobicić A, Petrak J. Croatian Medical Journal citation score in web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar. Croat Med J. 2010;51:99–103.

Yue Y-Y, Fan X-Y, Zhang Q, Lu Y-P, Wu S, Wang S, et al. Bibliometric analysis of subject trends and knowledge structures of gut microbiota. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:2817–32.

Yao H, Wan J-Y, Wang C-Z, Li L, Wang J, Li Y, et al. Bibliometric analysis of research on the role of intestinal microbiota in obesity. PeerJ. 2018;6:e5091.

Tian J, Li M, Lian F, Tong X. The hundred most-cited publications in microbiota of diabetes research. Med (Baltim). 2017;96:e7338.

Li Y, Zou Z, Bian X, Huang Y, Wang Y, Yang C, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation research output from 2004 to 2017: a bibliometric analysis. PeerJ. 2019;7:e6411.

Zhang T, Yin X, Yang X, Man J, He Q, Wu Q, et al. Research trends on the relationship between Microbiota and gastric Cancer: a bibliometric analysis from 2000 to 2019. J Cancer. 2020;11:4823–31.

Gofton C, Upendran Y, Zheng M-H, George J, Suppl. S17–31.

Sweileh WM. Analysis and mapping of Scientific Literature on Detention and Deportation of International migrants (1990–2022). J Immigr Minor Health. 2023;25:1065–76.

van Eck NJ, Waltman L. Text mining and visualization using VOSviewer. 2011.

van Eck NJ, Waltman L. VOSviewer Manual. 2023.

van Eck NJ, Waltman L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics. 2010;84:523–38.

Boursier J, Mueller O, Barret M, Machado M, Fizanne L, Araujo-Perez F, et al. The severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with gut dysbiosis and shift in the metabolic function of the gut microbiota. Hepatology. 2016;63:764–75.

Del Chierico F, Nobili V, Vernocchi P, Russo A, De Stefanis C, Gnani D, et al. Gut microbiota profiling of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and obese patients unveiled by an integrated meta-omics-based approach. Hepatology. 2017;65:451–64.

Jiang W, Wu N, Wang X, Chi Y, Zhang Y, Qiu X, et al. Dysbiosis gut microbiota associated with inflammation and impaired mucosal immune function in intestine of humans with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8096.

Le Roy T, Llopis M, Lepage P, Bruneau A, Rabot S, Bevilacqua C, et al. Intestinal microbiota determines development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Gut. 2013;62:1787–94.

Loomba R, Seguritan V, Li W, Long T, Klitgord N, Bhatt A, et al. Gut microbiome-based metagenomic signature for non-invasive detection of Advanced Fibrosis in Human nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell Metab. 2017;25:1054–e10625.

Mouzaki M, Comelli EM, Arendt BM, Bonengel J, Fung SK, Fischer SE, et al. Intestinal microbiota in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2013;58:120–7.

Raman M, Ahmed I, Gillevet PM, Probert CS, Ratcliffe NM, Smith S et al. Fecal microbiome and volatile organic compound metabolome in obese humans with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:868–875.e1-3.

Alkhouri N, De Vito R, Alisi A, Yerian L, Lopez R, Feldstein AE, et al. Development and validation of a new histological score for pediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2012;57:1312–8.

Bai A, Wu C, Yang K. Evolution and features of China’s Central Government Funding System for Basic Research. Front Res Metr Anal. 2021;6:751497.

Zhou Y. The rapid rise of a research nation. Nature. 2015;528:S170–3.

Wang X, Zhang A, Sun H. Future perspectives of Chinese Medical Formulae: Chinmedomics as an Effector. OMICS. 2012;16:414–21.

Yin J, Zhang H, Ye J. Traditional Chinese medicine in treatment of metabolic syndrome. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2008;8:99–111.

Zyoud SH, Shakhshir M, Abushanab AS, Al-Jabi SW, Koni A, Shahwan M, et al. Mapping the global research landscape on nutrition and the gut microbiota: visualization and bibliometric analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:2981–93.

Conroy G, Plackett B. Nature Index Annual table 2022: China’s research spending pays off. Nature. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-01669-0.

Braun D. The role of funding agencies in the cognitive development of science. Res Policy. 1998;27:807–21.

National Natural Science. Fund Guide to Programs 2020.pdf.

2022 National Natural Science Foundation of China. Wenzhou-Kean University. 2022. https://www.wku.edu.cn/en/2022/01/07/63749/. Accessed 13 Dec 2023.

Dzau VJ, Fineberg HV. Restore the US Lead in Biomedical Research. JAMA. 2015;313:143–4.

Wilson SH, Merkle S, Brown D, Moskowitz J, Hurley D, Brown D, et al. Biomedical research leaders: report on needs, opportunities, difficulties, education and training, and evaluation. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(Suppl 6):979–95.

NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH. RePORT. https://report.nih.gov/. Accessed 17 Dec 2023.

Proctor LM. The National Institutes of Health Human Microbiome Project. Seminars Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;21:368–72.

Shah FA, Jawaid SA. The h-Index: an Indicator of Research and Publication output. Pak J Med Sci. 2023;39:315–6.

Saltzman ET, Palacios T, Thomsen M, Vitetta L. Intestinal microbiome shifts, dysbiosis, inflammation, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Front Microbiol. 2018;9.

Jennison E, Byrne CD. The role of the gut microbiome and diet in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2021;27:22–43.

Quesada-Vázquez S, Aragonès G, Del Bas JM, Escoté X, Diet. Gut microbiota and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: three parts of the same Axis. Cells. 2020;9:176.

Steyn K, Damasceno A et al. Lifestyle and Related Risk Factors for Chronic Diseases. In: Jamison DT, Feachem RG, Makgoba MW, Bos ER, Baingana FK, Hofman KJ, editors. Disease and Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa. 2nd edition. Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank; 2006.

Żarnowski A, Jankowski M, Gujski M. Public awareness of Diet-Related diseases and Dietary Risk factors: a 2022 nationwide cross-sectional survey among adults in Poland. Nutrients. 2022;14:3285.

Willett WC, Koplan JP, Nugent R, Dusenbury C, Puska P, Gaziano TA et al. Prevention of Chronic Disease by Means of Diet and Lifestyle Changes. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, editors. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd edition. Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank; 2006.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks An-Najah National University for all the administrative assistance during the implementation of the project.

Funding

No support was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zyoud SH played a pivotal role in the conceptualization and design of the research project, overseeing the data management and analysis, generating figures, and making significant contributions to the literature search and interpretation. Additionally, Zyoud SH drafted the manuscript. Al-Jabi SW made substantial contributions to the study design, data screening and extraction, data interpretation, and preparation of the manuscript. Alalalmeh SO, Hegazi OE, Shakhshir MH, and Abushamma F were actively involved in the data interpretation, contributed to the writing of the manuscript, and participated in the initial draft revision. All the authors contributed to the writing and approved the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Because the current study did not include any human interactions, the approval of the Ethics Committee was not needed.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zyoud, S.H., Alalalmeh, S.O., Hegazi, O.E. et al. An examination of global research trends for exploring the associations between the gut microbiota and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease through bibliometric and visualization analysis. Gut Pathog 16, 31 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13099-024-00624-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13099-024-00624-w