Abstract

Background

Malaria is one of the most lethal infectious diseases in tropical and subtropical areas of the world. Paratransgenesis using symbiotic bacteria offers a sustainable and environmentally friendly strategy to combat this disease. In the study reported here, we evaluated the disruption of malaria transmission in the Anopheles stephensi-Plasmodium berghei assemblage using the wild-type (WT) and three modified strains of the insect gut bacterium, Enterobacter cloacae.

Methods

The assay was carried out using the E. cloacae dissolvens WT and three engineered strains (expressing green fluorescent protein-defensin (GFP-D), scorpine-HasA (S-HasA) and HasA only, respectively). Cotton wool soaked in a solution of 5% (wt/vol) fructose + red dye (1/50 ml) laced with one of the bacterial strains (1 × 109cells/ml) was placed overnight in cages containing female An. stephensi mosquitoes (age: 3–5 days). Each group of sugar-fed mosquitoes was then starved for 4–6 h, following which time they were allowed to blood-feed on P. berghei–infected mice for 20 min in the dark at 17–20 °C. The blood-fed mosquitoes were kept at 19 ± 1 °C and 80 ± 5% relative humidity, and parasite infection was measured by midgut dissection and oocyst counting 10 days post-infection (dpi).

Results

Exposure to both WT and genetically modified E. cloacae dissolvens strains significantly (P < 0.0001) disrupted P. berghei development in the midgut of An. stephensi, in comparison with the control group. The mean parasite inhibition of E. cloacaeWT, E. cloacaeHasA, E. cloacaeS−HasA and E. cloacaeGFP−D was measured as 72, 86, 92.5 and 92.8 respectively.

Conclusions

The WT and modified strains of E. cloacae have the potential to abolish oocyst development by providing a physical barrier or through the excretion of intrinsic effector molecules. These findings reinforce the case for the use of either WT or genetically modified strains of E. cloacae bacteria as a powerful tool to combat malaria.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Of the world's vector-borne diseases, malaria causes the greatest health concern, with a reported 229 million cases and 409,000 deaths globally in 2019 [1]. The Plasmodium parasite is the causative agent of malaria, and the female Anopheles mosquito is the vector of the disease. Anopheles stephensi is the main malaria vector throughout its range from Asia to the Horn of Africa [2,3,4,5]. Therefore, programs aimed at controlling A. stephensi populations and limiting the ability of these mosquitoes to transmit Plasmodium (refractory mosquitoes) have the potential to reduce the burden of malaria disease [6].

Currently, the most common methods of mosquito control are indoor residual spraying (IRS) and insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) [1, 7]. However, novel and innovative control measures are urgently needed due to emerging insecticide resistance in malaria vectors, particularly in A. stephensi [8,9,10], and increasing eco-environmental concerns about the off-target effects of insecticide use [11,12,13,14,15]. Transmission-blocking strategies (TBS) have recently been proposed as a potential means of malaria control, with an increased emphasis on inhibiting the development of the Plasmodium parasite in the vector mosquito [16,17,18,19]. Gametocytocidal drugs, transmission-blocking vaccines and the replacement of wild mosquitoes with refractory mosquitoes are currently the most important methods used in TBS. The last method consists of genetically manipulating Anopheles mosquitoes to render them refractory to Plasmodium parasite development. This is accomplished using anti-plasmodium molecules (transgenesis) [20], naturally refractory mosquitoes [21], artificial gene-drive mechanisms [22, 23] and/or micro-symbionts genetically modified by effector molecules that are reintroduced into the wild mosquito population (paratransgenesis) [6, 12, 24, 25].

During its development in its invertebrate hosts (vectors), the Plasmodium parasite undergoes a decreasing population trend, from 103–104 gametocytes to 102–103 motile ookinetes and, finally, to ≤ 5 oocysts [26, 27]. This bottleneck could be considered a prime target for intervention and the blocking of parasite transmission [28, 29]. The main factors creating the bottleneck include gut digestive enzymes, the mosquito's immune responses and intestinal microbial flora. The intestinal microbial flora plays a vital role in blocking parasite development in the Anopheles midgut. This effect is exerted directly by the proliferation of bacteria after a blood meal, simultaneously with the development of the ookinete stage, and indirectly via the expression of antimicrobial genes [30,31,32,33,34,35,36].

To date, a number of different symbiotic bacteria have been suggested for use in a paratransgenesis strategy for combating malaria. Serratia AS1 (isolated from Anopheles spp.), Asaia sp. (isolated from Anopheles gambiae, An. stephensi, Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti) and Pantoea agglomerans (isolated from An. stephensi, An. gambiae and Anopheles funestus) are the bacterial species most commonly used for the paratransgenic control of malaria [11, 25, 27, 31, 37,38,39,40,41]. These genetically modified bacteria could potentially eliminate the development of the Plasmodium parasite in the Anopheles midgut by expressing anti-Plasmodium molecules. However, due to convergent evolution, the wild-type (WT) bacteria have shown limited intrinsic antiparasitic activities in the mosquito midgut [27, 42].

Enterobacter cloacae, a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped bacterium, has been found to be a component of the microflora of An. stephensi [43, 44], Anopheles albimanus [45], Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti [46], as well as of other medically important insects [47, 48]. This bacterium has been shown to have an innate blocking effect on Plasmodium development and could potentially limit P. berghei and P. falciparum development in An. stephensi by markedly increasing the population, thereby leading to stimulation of the mosquito immune system and expression of immune response compounds, such as serine protease inhibitors (SRPN6) [49]. These innate features suggest that E. cloacae is a suitable candidate for paratransgenesis studies against the malaria parasite.

Scorpine is a small cationic antimicrobial peptide (AMP) found in the venom of the scorpion Pandinus imperator with anti-plasmodial and anti-bacterial activity, and also a strong inhibition of dengue 2 virus (DENV-2) infection [50,51,52]. Defensins are small cysteine-rich cationic proteins that are found in plants, vertebrates and invertebrates [53,54,55]. Scorpine has been used as effector molecule against malaria parasites in paratransgenic mosquitoes carrying scorpine-secreting bacteria or fungi [11, 27, 56]. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the transmission-blocking potential of WT and engineered strains of E. cloacae expressing defensin and scorpine effector molecules to block P. berghei development in An. stephensi.

Methods

Mosquito rearing

Anopheles stephensi, Beech strain, was used in this study. The strain was originally collected in Pakistan as an additional type of the SDA500 strain and was kindly provided in 2005 by Professor P.F. Billingsley, Sanaria, Inc. [57]. Mosquitoes were maintained on a 5% (wt/vol) fructose solution at 27 ± 1 °C and 65 ± 5% relative humidity (RH) under a 12:12 dark:light (D:L) photoperiod. All mosquito-rearing facilities were provided by Tehran University of Medical Sciences, School of Public Health.

Maintenance of parasite life-cycle

BALB/c mice aged 6 weeks (weight 8–20 g) were used in this study. The mouse colonies were maintained in an animal house at 40–50% RH and 24 ± 1 °C. The P. berghei ANKA strain was used, specifically clone 2.34 (a gift from Prof. Marcelo Jacob-Lorena, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA). Parasites were maintained using previously described protocols [58, 59]. Briefly, the parasites were maintained in female BALB/c mice by serial mechanical passages (3 or 4 passages). To maintain gametocyte infectivity to mosquitoes, in direct passages, hyper-reticulocytosis was induced 3 days before infection by treating each mouse with 100 μl 1% phenylhydrazinium chloride (PH) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) administered intraperitoneally (ip; 10 mg/ml in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) per 10 g mouse body weight. Parasitemia was monitored in Giemsa-stained tail-blood smears. Exflagellation was examined at 5–6 days post-infection (dpi) (dose of injected parasite: approx. 104) by mixing a drop of infected blood (4-5 µl) with 20–25 μl ookinete culture medium (RPMI 1640 medium containing L-glutamine and 25 mM HEPES, 2 g/l NaHCO, 50 mg/l hypoxanthine, 50,000 U/l penicillin and 50 mg/l streptomycin; pH 8.3, filter sterilized). Mice with approximately three exflagellation centers in each field of 40× microscopic magnification were used in the transmission blocking assay (Fig. 1).

Schematic illustration of the transmission blocking assay. Steps 1–3: Infection of mouse with Plasmodium berghei ANKA strain clone 2.34 (a shows the introduction of bacteria into the mosquito midgut via sugar bait feeding). Steps 4, 5 Sugar-fed mosquitoes are fasted for 4–6 h (4), following which they blood-feed on a P. berghei-infected mouse (5). Step 6 Dissection of the mosquito midgut, staining with 0.5% mercurochrome and counting of the infective oocysts under the light microscope

Transformation of bacteria

The E. cloacae dissolvens subspecies used in this study was originally isolated by sampling the midgut microflora of the sand fly Phlebotomus papatasi, found in the main zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis foci in central Iran. The procedures used for isolating, characterizing and identifying this bacterium have been outlined previously [47]. We genetically engineered two different E. cloacae strains to produce: (1) a strain containing defensin (a peptide isolated from radish seeds, Rs-AFP [60]) plus green fluorescent protein (GFP), referred to here as E. cloacaeGFP−D), and (2) a strain containing Scorpine-HasA (scorpion Pandinus imperator venom) plus HasA, a heme-binding protein as an exporting system [61], referred to here as E. cloacaeS−HasA. Defensin and scorpine proteins are anti-malarial effector molecules with different killing mechanisms. As a control, we also genetically engineered a strain of E. cloacae to produce only HasA, referred to here as E. cloacaeHasA. The transgenic E. cloacaeGFP−D strain with the originally manipulated pBR322 plasmid was used in this study. The engineered pBR322 plasmid containing the defensin gene as effector molecule plus a GFP marker and tetracycline resistance genes, called the pBR/DG plasmid, is maintained in Tehran University of Medical Sciences (Fig. 2). The β-lactamase gene of the plasmid was replaced with the DG construct. A detailed description of the construct is provided in Additional file 1: Dataset S1. The recombinant plasmid was electro-transformed first to the recipient strain of Escherichia coli-DH5α and then to E. cloacae dissolvens cells. This strain is distinguishable from other similar bacteria colonies its green fluorescence under microscopy (Fig. 3). For construct verification, it was amplified from the pBR/DG plasmid using the forward primer DGFP1 (5′-GGA ATT CAA ATA CAT TCA AAT ATG TAT CCG-3′) and the reverse primer DGFP7 (5′-TTC TGC AGT TAT TAT TTG TAT AGT TCA TCC ATG-3′). The pBR/DG and pBR322 plasmids also were digested at the EcoRI and Pst1 restriction sites which were incorporated at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the construct, respectively. The digested plasmids were electrophoresed in 1% agarose gel (Additional file 2: Fig. S1).

Schematic illustration of the defensin-GFP (DG) construct and its position in the pBR322 plasmid. Abbreviations: Pro, promotor; RBS1 and RBS2, ribosomal binding site numbers 1 and 2, respectively; Sig Pep, signal peptide; Rs-AP1, defensin; GFP, green fluorescent protein. The EcoRI and Pst1 restriction sites are at the 5′ and 3′ end of the construct

The proteins were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) to detect the secreted defensin molecules from the E. cloacae dissolvens strain carrying the pBR/DG plasmid [62]. For this purpose, the recombinant strain was grown overnight at 37 °C in LB liquid medium containing the tetracycline (12.5 µg/ml) antibiotics. Bacterial cultures were centrifuged at 4000 g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected and separated by 13% gradient SDS-PAGE. The supernatant from WT E. cloacae dissolvens was used as a control.

We used two plasmids, including PDB47-Scorpine-HasA and PDB47-HasA hosted in Serratia AS1 (a gift from Prof. Marcelo Jacob-Lorena, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA) [11]. The plasmids were extracted and transferred into the WT E. cloacae dissolvens.

Transmission-blocking assay

The transmission-blocking assay was carried out using WT/engineered bacteria, including the ampicillin-resistant E. cloacae WT, the ampicillin- and tetracycline-resistant E. cloacaeGFP−D strain and the ampicillin- and apramycin-resistant E. cloacaeHasA and E. cloacaeS−HasA strains. The bacterial strains were cultured in BHI broth at 37 °C, and antibiotics, including ampicillin (100 μg/ml), tetracycline (12.5 μg/ml) and apramycin (80 μg/mL) were added to the media based on their antibiotic resistance patterns. After overnight growth, the bacteria were harvested by centrifugation (3000 g, 10 min), washed twice in sterile PBS and resuspended (5% wt/vol)in a sterile fructose and red dye (1/50 ml) solution (Nilgoon®, Tehran, Iran) to obtain a concentration of 109 cells/ml.

Female mosquitoes aged 3–5 days were placed in five groups, each containing 25 females, and fed on sterile cotton wool soaked in the fructose + dye solution, with or without bacterial cells, for 24 h. As each mosquito became satiated with the sugar solution, as identified by the red dye, they were separated via a sucking tube and transferred into another cage where they were starved for 4–6 h prior to being allowed to feed on infected blood. Each of the five groups of mosquitoes (each comprising 15–20 females) were fed on the same P. berghei-infected mouse. The infected blood-feeding process was carried out at 17–20 °C for 20 min, and the infected blood-fed mosquitoes were maintained on 5% fructose/0.05% para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) at 19 ± 1 °C and 75 ± 5% RH under a 12:12 D:L photoperiod. Data were pooled from four biological replicates.

In total, we dissected midguts from 248 mosquitoes (45–51 females in each group) at 10 days post-infected blood-feed (dpi); these midguts were stained with 0.5% (wt/vol) mercurochrome (Aldrich–Sigma). Plasmodium oocyst development was examined by light microscopy and the oocysts were counted (Fig. 1).

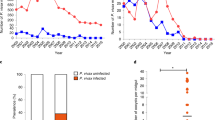

A subset of the sugar-fed females infected with bacteria, as well as the blood-fed specimens, were tested for the presence and proliferation of the bacteria by midgut dissection at 0, 12, 18, 24, and 36 h post-blood meal (Fig. 4). The population dynamics of the engineered bacteria colony-forming units (CFUs) were defined by plating serially diluted homogenates of midguts on LB agar plates containing 100 μg/ml of the appropriate antibiotics.

Trends of E. cloacae proliferation in the mosquito midgut. a Digestion of blood meal in paratransgenic Anopheles stephensi over time. b The frequency of E. cloacaeGFP-D in the An. stephensi midgut at different times (T) after ingestion of a blood meal. c Schematic development of the Plasmodium parasite in Anopheles midgut shows simultaneous bacterial proliferation and ookinete formation at 18–24 h after a blood meal

All experiments on the rodents were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Ethical Board of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS), Iran.

Statistical analyses

The normality of data was checked using the Shapiro-Wilks test. Significant differences in oocyst intensities between two samples were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney test. Multiple-sample comparisons were analyzed using the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test, and means and medians were compared using Dunn’s test. All statistics were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). A P-value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Proliferation of bacteria in mosquito midgut

The dynamics of the engineered bacteria showed that, in general, the bacteria were easily established in the mosquito midgut through feeding the mosquitoes on sugar meals laced with bacteria. The bacteria proliferated strongly in the mosquito midgut after ingestion of a blood meal and became the dominant microflora of the midgut, based on the number of CFUs in the plates. Enterobacter cloacae dynamics were monitored at different times post-blood meal by dissection of the midgut and plating of the midgut homogenates on selective antibiotic-containing plates. The number of engineered bacteria increased dramatically, by more than approximately 10,000-fold at 24 h after ingestion of a blood meal (Fig. 4a, b), and the rapid propagation of transgenic E. cloacae occurred simultaneously with the development of the ookinete stage of the Plasmodium parasite in the mosquito gut (Fig. 4c, 5).

The presence or absence of motile ookinetes (barrel-shaped, shown by arrows) of P. berghei in the midgut of An. stephensi mosquitoes in the control and E. cloacaeGFP-D (Test) group at 20–24 h after ingestion of an infected blood meal. Upper panels: Presence of P. berghei ookinetes are seen in the remains of digested red blood cells in the mosquito midgut in the absence of E. cloacae bacteria. Lower panels: Strong proliferation of E. cloacaeGFP-D bacteria correlates with a lack of ookinetes 20 h after ingestion of an infected blood meal with 104–105 parasites/µl in the midgut. The thick smear was stained by Giemsa. The bacteria in the dissected An. stephensi midgut (squares) were transferred to BHI agar plates and found to express GFP under the fluorescent (Fig. 3b) microscope

Transmission blocking assay

The oocyst numbers in the mosquito midguts were counted on 10 dpi. The median values of all strains of WT or transgenic bacteria significantly (P < 0.0001) impaired the development of P. berghei in the An. stephensi midgut, in comparison with the control group (Table 1).

The WT strain of E. cloacae was found to inhibit oocyst formation by approximately 72%, in comparison with the control group (without bacteria). The transgenic E. cloacae strain expressing the HasA protein alone inhibited oocyst formation by 86%, while the transgenic E. cloacae strain expressing both the HasA and scorpine proteins inhibited oocyst formation by 92.5%. The transgenic E. cloacae strain expressing the defensin protein had the greatest inhibitory effect (92.8%) on oocyst formation. Importantly, the infection prevalence (the percentage of mosquitoes that had ≥ 1 oocysts) was 86.3% in the control group, which was reduced to 47.1, 25 and 20% in paratransgenic mosquitoes with the WT type, GFP-D and S-HasA strains, respectively. The transmission-blocking potential (TBP) index was determined in paratransgenic mosquitoes with the WT, GFP-D and S-HasA strains was determined to be 45.4, 71 and 76.8, respectively (Fig. 6).

Inhibition of P. berghei development in An. stephensi by WT and transgenic E. cloacae strains. Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes were fed on 5% (wt/vol) fructose solution + red food dye supplemented with either phosphate-buffered saline (control) or with WT or transgenic E. cloacae strains in five groups. After 8 h, the five groups of mosquitoes were fed on the same P. berghei-infected mice. Oocyst numbers were determined 10 days after the infected blood meal. Data were pooled from four biological replicates. Each dot denotes the oocyst number of an individual midgut, and horizontal lines show mean values. %inhibition refers to the inhibition of oocyst formation relative to the control. Mean refers to the mean oocyst number per midgut. Median refers to the median oocyst number per midgut. N is the number of mosquitoes analyzed. Prevalence refers to the percentage of mosquitoes carrying at least one oocyst. Range refers to the range of oocyst numbers per midgut. TBP: 100 − {(prevalence of mosquitoes fed with transgenic E. cloacae)/[prevalence of control (− Bacteria) mosquitoes] × 100}. Inhibition refers to the inhibition of oocyst formation relative to the control. Abbreviations: Cont, control group without bacteria; Wild, E. cloacae WT; HasA, E. cloacaeHasA; Scor., E. cloacaeS−HasA; Def., E. cloacaeGFP−D; TBP, transmission blocking potential

Discussion

The Plasmodium parasite is very vulnerable in the mosquito midgut and, consequently, components of the midgut microbiome could negatively affect parasite development in several ways, such as by impairing its development through secreting anti-parasitic compounds, by activating the host immune system and/or by competing with the parasite for available space in the midgut [6, 27]. Enterbacter cloacae is a known symbiont of the gut microflora of most Anopheles species; as such, it has been suggested as a good candidate for the paratransgenic control of malaria [63]. In our study, transgenic E. cloacae showed rapid propagation by 18–24 h after the mosquito consumed the blood meal, suggesting it can block parasite development by competing for the same space as the parasite (Figs. 4c, 5), by a greatly increased expression of anti-plasmodium molecules that lyse the Plasmodium parasite in the Anopheles midgut (Fig. 6) and by activating the mosquito immune system against the bacteria, which also leads to parasite control [49].

The present study was designed to investigate the efficacy of different strains of E. cloacae in disrupting P. berghei development, while previous studies have investigated different aspects of E. cloacae [45, 49, 63, 64]. In our study, we showed that E. cloacae multiplied rapidly in the mosquito midgut, and that by 18–24 h after ingestion of a blood meal it was the dominant species in the midgut microflora. This was shown by the GFP marker and by culturing the mosquito's midgut contents at different times after the blood meal. Similarly, Pumpuni et al. [31] showed that the midgut bacterial load of An. gambiae and An. stephensi increased by 11–40 fold by 24 h after blood-feeding. Demaio et al. [65] also obtained similar results in Aedes triseriatus, Culex pipiens and Psorophora columbiae, and Wang et al. [27] reported that the bacterial load of Plasmodium agglomerans increased by 200-fold in the An. stephensi midgut by 24–48 h after ingestion of a blood meal. The finding of Dehghan et al. [63], that E. cloacae was highly stable in a sugar solution, suggested that using sugar bait stations to introduce the transgenic bacteria in the field could be a feasible paratransgenic approach.

It is known that the development of the Plasmodium parasite could be affected by the presence of certain bacteria in the microflora of the mosquito midgut. In this study, the interaction of E. cloacae and P. berghei in vivo led to a significant inhibition of oocyst formation, relative to the control group (P-value < 0.0001). This correlates well with the findings of Pumpuni et al. [30] who reported that the presence of 100,000 Ewingella americana cells in the mosquito midgut reduced the P. falciparum infection rate to zero and those of Gonzalez-Ceron et al. [45] who reported a reduction in the P. vivax infection rate in An. albimanus in the presence Serratia marcescens, E. cloacae and Enterobacter amnigenus. In this regard, the coincidence of bacterial multiplication with the ookinete stage in the Anopheles gut will affect the bacteria–parasite interaction both directly and indirectly. We showed that transgenic bacteria could overcome the harsh environment and barriers in the Anopheles midgut, such as digestive enzymes, to become the dominant component of the gut microflora, leading to an increase in the expression of antiparasitic molecules. This correlates well with the findings of Dong et al. [32], who showed that when the Chryseobacterium meningosepticum bacterium entered the An. gambiae midgut, it rapidly became a dominant species, indicating the competitive nature of this bacterium in the midgut environment.

The results of this study showed that all of the bacterial strains tested disrupted the development of P. berghei to a significant degree, compared with the control group (P < 0.0001). Even the E. cloacae WT led to significantly impaired parasite development (P < 0.0001), indicating the inherent effect of these bacteria in parasite control. The transgenic E. cloacae GFP−D strain, expressing defensin, inhibited parasite development still further compared with the WT (P = 0.003), indicating the suppressive effect of defensin, which lyses the parasite inside the mosquito gut [66,67,68]. The inhibitory effect of scorpine was very similar to that of defensin, and we saw no significant differences in inhibition of oocyst formation between E. cloacaeS−HasA and E. cloacaeGFP−D (P = 0.051). Similarly, Kokoza et al. [66] expressed cecropin A and defensin A in Ae. aegypti mosquitoes to control P. gallinaceum, and reported that Plasmodium transmission was completely blocked.

Scorpine is an anti-malarial peptide from the venom of the Pandinus imperator scorpion and its amino acid sequence is very similar to those of cecropin and defensin, which has led to the suggestion that scorpine might have a similarly inhibitory effect on the P. berghei [50]. Indeed, Conde et al. [50] found that it completely inhibited P. berghei fertilization and oocyst formation. Wang et al. [11, 27] reported that the symbiotic bacteria, P. agglomerans and Serratia AS1, transgenically expressing scorpine, could inhibit P. falciparum development in An. gambiae by 98% and 93%, respectively. The additional expression of HasA protein in the E. cloacaeS−HasA strain was found to enhance the anti-Plasmodiun effectiveness of scorpine. It is possible that HasA could create a membrane pore in the E. cloacae wall to allow the direct export of scorpine protein from the bacterial cytoplasm into the mosquito midgut.

Three bacterial species have previously been proposed as candidates for paratransgenetic malaria control: Serratia AS1, Asaia sp. and P. agglomerans; these species transgenically express anti-Plasmodium proteins and have been demonstrated to be suitable micro-symbionts in the mosquito midgut [27, 42]. Here, we evaluated a new candidate bacterium, E. cloacae, and showed that it has a strong innate control effect on the Plasmodium parasite in the mosquito midgut, and that this effect could be enhanced by the transgenic expression of anti-Plasmodium proteins.

The symbiotic bacterium Asaia, transgenically expressing scorpine, has previously been shown to inhibit P. berghei development by 63% in the An. stephensi midgut [42]; in comparison, we found that, when expressed in E. cloacae, scorpine caused a 92.5% inhibition of oocyst formation. This remarkable difference is most likely due to the inherent antiparasitic activity of the E. cloacae bacterium. In addition, Wang et al. [27] reported that the expression in P. agglomerans of HlyA protein (which, like HasA, causes pore formation in the bacterial wall) had a negligible effect (21.2%) on parasite development. Therefore, E. cloacae, owing to its intrinsic antiparasitic properties could be preferred to other paratransgenesis candidates such as Asaia sp. and P. agglomerans. This advantage can be attributed to the stimulation of the mosquito's immune system and the secretion of serine protease inhibitors, which are produced by mosquitoes to control bacteria, but which are not specific to the target organism and are suppressed if the Plasmodium parasite is present in the midgut [49]. The E. cloacae bacterium is found in the normal gastrointestinal micro-flora of humans and many other animals and is generally reported to be widespread in insect midguts [43, 45, 64, 69, 70], thus alleviating any potential safety concerns concerning its release in the field.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we consider an alternative strategy for control of the Plasmodium parasite that involves the use of bacterial symbionts of the mosquito, genetically engineered to express anti-Plasmodium effector molecules. The paratransgenesis strategy converts the proven mosquito vector into an ineffective disease vector. This approach could be effective for multiple mosquito and parasite species concomitantly. The findings of the present study provide the foundation for the use of either WT or genetically modified E. cloacae bacteria as a powerful tool to combat malaria. However, further studies are needed to determine how effectively these bacterial strains can be established in the field and the conditions required to do this.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the findings of this article are included within the article and its additional files.

Abbreviations

- CFUs:

-

Colony-forming units

- dpi:

-

Days post-infection

- GFP-D:

-

GFP-defensin

- ip:

-

Intra-peritoneal

- IRS:

-

Indoor residual spraying

- ITNs:

-

Insecticide-treated nets

- PABA:

-

Para-aminobenzoic acid

- S-HasA:

-

Scorpine-HasA

- SRPN6:

-

Serine protease inhibitors

- TBS:

-

Transmission-blocking strategy

- WT:

-

Wild type

References

World Health Organization. World malaria report 2020: 20 years of global progress and challenges. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240015791.

Ashine T, Teka H, Esayas E, Messenger LA, Chali W, Meerstein-Kessel L, et al. Anopheles stephensi as an emerging malaria vector in the Horn of Africa with high susceptibility to Ethiopian Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum isolates. bioRxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.22.961284.

Sinka M, Pironon S, Massey N, Longbottom J, Hemingway J, Moyes C, et al. A new malaria vector in Africa: predicting the expansion range of Anopheles stephensi and identifying the urban populations at risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(40):24900–8. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2003976117.

Vatandoost H, Oshaghi MA, Abaie MR, Shahi M, Yaaghoobi F, Baghaii M, et al. Bionomics of Anopheles stephensi Liston in the malarious area of Hormozgan province, southern Iran, 2002. Acta Trop. 2006;97(2):196–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.11.002.

Chavshin AR, Oshaghi MA, Vatandoost H, Hanafi-Bojd AA, Raeisi A, Nikpoor F. Molecular characterization, biological forms and sporozoite rate of Anopheles stephensi in southern Iran. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2014;4(1):47–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2221-1691(14)60207-0.

Kotnis B, Kuri J. Evaluating the usefulness of paratransgenesis for malaria control. Math Biosci. 2016;277:117–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mbs.2016.04.005.

Raghavendra K, Barik TK, Reddy BPN, Sharma P, Dash AP. Malaria vector control: from past to future. Parasitol Res. 2011;108(4):757–79.

Enayati A, Hanafi-Bojd AA, Sedaghat MM, Zaim M, Hemingway J. Evolution of insecticide resistance and its mechanisms in Anopheles stephensi in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region. Malar J. 2020;19(1):258. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-020-03335-0.

Gorouhi MA, Oshaghi MA, Vatandoost H, Enayati AA, Raeisi A, Abai MR, et al. Biochemical basis of cyfluthrin and DDT resistance in Anopheles stephensi (Diptera: Culicidae) in malarious area of Iran. J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2018;12(3):310–20.

Soltani A, Vatandoost H, Oshaghi MA, Ravasan NM, Enayati AA, Asgarian F. Resistance mechanisms of Anopheles stephensi (Diptera: Culicidae) to temephos. J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2014;9(1):71–83.

Wang S, Dos-Santos ALA, Huang W, Liu KC, Oshaghi MA, Wei G, et al. Driving mosquito refractoriness to Plasmodium falciparum with engineered symbiotic bacteria. Science. 2017;357(6358):1399–402. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan5478.

Koosha M, Vatandoost H, Karimian F, Choubdar N, Oshaghi MA. Delivery of a genetically marked Serratia AS1 to medically important arthropods for use in RNAi and paratransgenic control strategies. Microb Ecol. 2019;78(1):185–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-018-1289-7.

Shaw WR, Catteruccia F. Vector biology meets disease control: using basic research to fight vector-borne diseases. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4(1):20–34. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-018-0214-7.

Chavshin AR, Oshaghi MA, Vatandoost H, Yakhchali B, Zarenejad F, Terenius O. Malpighian tubules are important determinants of Pseudomonas transstadial transmission and longtime persistence in Anopheles stephensi. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-0635-6.

Chavshin AR, Oshaghi MA, Vatandoost H, Pourmand MR, Raeisi A, Terenius O. Isolation and identification of culturable bacteria from wild Anopheles culicifacies, a first step in a paratransgenesis approach. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:419. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-419.

Pradel G. Proteins of the malaria parasite sexual stages: expression, function and potential for transmission blocking strategies. Parasitology. 2007;134:1911–29.

Gonçalves D, Hunziker P. Transmission-blocking strategies: the roadmap from laboratory bench to the community. Malar J. 2016;15:95. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-016-1163-3.

Sinden RE. Developing transmission-blocking strategies for malaria control. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(7):e1006336. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1006336.

Bompard A, Da DF, Yerbanga RS, Biswas S, Kapulu M, Bousema T, et al. Evaluation of two lead malaria transmission blocking vaccine candidate antibodies in natural parasite-vector combinations. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):6766. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-06130-1.

Knols BG, Bossin HC, Mukabana WR, Robinson AS. Transgenic mosquitoes and the fight against malaria: managing technology push in a turbulent GMO world. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:232–42.

Zieler H, Keister DB, Dvorak JA, Ribeiro JM. A snake venom phospholipase A(2) blocks malaria parasite development in the mosquito midgut by inhibiting ookinete association with the midgut surface. J Exp Biol. 2001;204:4157–67.

Windbichler N, Menichelli M, Papathanos PA, Thyme SB, Li H, Ulge UY, et al. A synthetic homing endonuclease-based gene drive system in the human malaria mosquito. Nature. 2011;473:212–5.

Gantza VM, Jasinskiene N, Tatarenkova O, Fazekas A, Macias VM, Bier E, et al. Highly efficient Cas9-mediated gene drive for population modification of the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles stephensi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:6736–43.

Durvasula RV, Gumbs A, Panackal A, Kruglov O, Aksoy S, Merrifield RB, et al. Prevention of insect-borne disease: an approach using transgenic symbiotic bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3274–8.

Riehle MA, Moreira CK, Lampe D, Lauzon C, Jacobs-Lorena M. Using bacteria to express and display anti-Plasmodium molecules in the mosquito midgut. Int J Parasitol. 2007;37:595–603.

Whitten MMA, Shiao SH. Levashina EA Mosquito midguts and malaria: cell biology, compartmentalization and immunology. Parasite Immunol. 2006;28:121–30.

Wang S, Ghosh AK, Bongio N, Stebbings KA, Lampe DJ, Jacobs-Lorena M. Fighting malaria with engineered symbiotic bacteria from vector mosquitoes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:12734–9.

Abraham EG, Jacobs-Lorena M. Mosquito midgut barriers to malaria parasite development. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34:667–71.

Drexler AL, Vodovotz Y, Luckhart S. Plasmodium development in the mosquito: biology bottlenecks and opportunities for mathematical modeling. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24:333–6.

Pumpuni CB, Beier MS, Nataro JP, Guers LD, Davis JR. Plasmodium falciparum: inhibition of sporogonic development in Anopheles stephensi by gram-negative bacteria. Exp Parasitol. 1993;77:195–9.

Pumpuni CB, Demaio J, Kent M, Davis JR, Beier JC. Bacterial population dynamics in three Anopheline species: the impact on Plasmodium sporogonic development. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:214–8.

Dong Y, Manfredini F, Dimopoulos G. Implication of the mosquito midgut microbiota in the defense against malaria parasites. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000423.

Meister S, Agianian B, Turlure F, Relógio A, Morlais I, Kafatos FC, et al. Anopheles gambiae PGRPLC-mediated defense against bacteria modulates infections with malaria parasites. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000542.

Rodrigues J, Brayner FA, Alves LC, Dixit R, Barillas-Mury C. Hemocyte differentiation mediates innate immune memory in Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. Science. 2010;329:1353–5.

Kumar S, Molina-Cruz A, Gupta L, Rodrigues J, Barillas-Mury C. A peroxidase/dual oxidase system modulates midgut epithelial immunity in Anopheles gambiae. Science. 2010;327:1644–8.

Cirimotich CM, Dong Y, Garver LS, Sim S, Dimopoulos G. Mosquito immune defenses against Plasmodium infection. Dev Comp Immunol. 2010;34:387–95.

Straif SC, Mbogo CN, Toure AM, Walker ED, Kaufman M, Toure YT, et al. Midgut bacteria in Anopheles gambiae and An. funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) from Kenya and Mali. J Med Entomol. 1998;35(3):222–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/35.3.222.

Damiani C, Ricci I, Crotti E, Rossi P, Rizzi A, Scuppa P, et al. Paternal transmission of symbiotic bacteria in malaria vectors. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1087–8.

Damiani C, Ricci I, Crotti E, Rossi P, Rizzi A, Scuppa P, et al. Mosquito-bacteria symbiosis: the case of Anopheles gambiae and Asaia. Microb Ecol. 2010;60:644–54.

De Freece C, Damiani C, Valzano M, D’Amelio S, Cappelli A, Ricci I, et al. Detection and isolation of the α-proteobacterium Asaia in Culex mosquitoes. Med Vet Entomol. 2014;28:438–42.

Favia G, Ricci I, Damiani C, Raddadi N, Crotti E, Marzorati M, et al. Bacteria of the genus Asaia stably associates with Anopheles stephensi, an Asian malarial mosquito vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:9047–51.

Bongio NJ, Lampe DJ. Inhibition of Plasmodium berghei development in mosquitoes by effector proteins secreted from Asaia sp. bacteria using a novel native secretion signal. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0143541.

Rani A, Sharma A, Rajagopal R, Adak T, Bhatnagar R. Bacterial diversity analysis of larvae and adult midgut microflora using culture-dependent and culture-independent methods in lab-reared and field-collected Anopheles stephensi an Asian malarial vector. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:96.

Chavshin AR, Oshaghi MA, Vatandoost H, Pourmand MR, Raeisi A, Enayati AA, et al. Identification of bacterial microflora in the midgut of the larvae and adult of wild caught Anopheles stephensi: a step toward finding suitable paratransgenesis candidates. Acta Trop. 2012;121(2):129–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.10.015.

Gonzalez-Ceron L, Santillan F, Rodriguez MH, Mendez D, Hernandez-Avila JE. Bacteria in midguts of field-collected Anopheles albimanus block Plasmodium vivax sporogonic development. J Med Entomol. 2003;40:371–4.

Yadav KK, Bora A, Datta S, Chandel K, Gogoi HK, Prasad GB, et al. Molecular characterization of midgut microbiota of Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti from Arunachal Pradesh, India. Parasit Vectors. 2015;18(8):641.

Maleki-Ravasan N, Oshaghi MA, Afshar D, Arandian MH, Hajikhani S, Akhavan AH, et al. Aerobic bacterial flora of biotic and abiotic compartments of a hyperendemic Zoonotic Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (ZCL) focus. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-014-0517-3.

Akbari S, Oshaghi MA, Hashemi-Aghdam SS, Hajikhani S, Oshaghi G, Shirazi MH. Aerobic bacterial community of American Cockroach Periplaneta americana, a step toward finding suitable paratransgenesis candidates. J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2014;9(1):35–48.

Eappen AG, Smith RC, Jacobs-Lorena M. Enterobacter-activated mosquito immune responses to plasmodium involve activation of SRPN6 in Anopheles stephensi. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e62937.

Conde R, Zamudio FZ, Rodríguez MH, Possani LD. Scorpine, an anti-malaria and anti-bacterial agent purified from scorpion venom. FEBS Lett. 2000;471:165–8.

Carballar-Lejarazú R, Rodríguez MH, de la Cruz H-H, Ramos-Castañeda J, Possani LD, Zurita-Ortega M, Reynaud-Garza E, Hernández-Rivas R, Loukeris T, Lycett G, Lanz-Mendoza H. Recombinant scorpine: a multifunctional antimicrobial peptide with activity against different pathogens. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65(19):3081–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-008-8250-8.

Zhang C, He X, Gu Y, Zhou H, Cao J, Gao Q. Recombinant scorpine produced using SUMO fusion partner in Escherichia coli has the activities against clinically isolated bacteria and inhibits the Plasmodium falciparum parasitemia in vitro. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):e103456. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0103456.

François IE, De Bolle MF, Dwyer G, Goderis IJ, Woutors PF, Verhaert PD, et al. Transgenic expression in Arabidopsis of a polyprotein construct leading to production of two different antimicrobial proteins. Plant Physiol. 2002;128(4):1346–58. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.010794.

Cabezas-Cruz A, Tonk M, Bouchut A, Pierrot C, Pierce RJ, Kotsyfakis M, et al. Antiplasmodial activity is an ancient and conserved feature of tick defensins. Front Microbiol. 2016;24(7):1682. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01682.

El-Dirany R, Shahrour H, Dirany Z, Abdel-Sater F, Gonzalez-Gaitano G, Brandenburg K, et al. Activity of anti-microbial peptides (AMPs) against Leishmania and other parasites: an overview. Biomolecules. 2021;11(7):984. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11070984.

Fang W, Vega-Rodríguez J, Ghosh AK, Jacobs-Lorena M, Kang A, St Leger RJ. Development of transgenic fungi that kill human malaria parasites in mosquitoes. Science. 2011;331(6020):1074–7. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1199115.

Basseri HR, Mohamadzadeh Hajipirloo H, Mohammadi Bavani M, Whitten MM. Comparative susceptibility of different biological forms of Anopheles stephensi to Plasmodium berghei ANKA strain. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(9):1–8.

Sinden RE, Butcher GA, Beetsma AL. Maintenance of the Plasmodium berghei life cycle, In: Doolan DL (ed). Malaria methods and protocols. Totowa: Humana Press;, 2002. p. 25–40.

Dehghan H, Oshaghi MA, Mosa-Kazemi SH, Abai MR, Rafie F, Nateghpour M, et al. Experimental study on Plasmodium berghei, Anopheles Stephensi, and BALB/c mouse system: implications for malaria transmission blocking assays. Iran J Parasitol. 2018;13(4):549–59.

Lacerda AF, Vasconcelos EA, Pelegrini PB, Grossi de Sa MF. Antifungal defensins and their role in plant defense. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:116. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00116.

Létoffé S, Ghigo JM, Wandersman C. Secretion of the Serratia marcescens HasA protein by an ABC transporter. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5372–7. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.176.17.5372-5377.

Sambrook JF, Russell DW. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 3rd ed. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001.

Dehghan H, Oshaghi MA, Moosa-Kazemi SH, Yakhchali B, Vatandoost H, Maleki-Ravasan N, et al. Dynamics of transgenic Enterobacter cloacae expressing green fluorescent protein defensin (GFP-D) in Anopheles stephensi under laboratory condition. J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2017;11(4):515–32.

Gouveia C, Asensi MD, Zahner V, Rangel EF, Oliveira SM. Study on the bacterial midgut microbiota associated to different Brazilian populations of Lutzomyia longipalpis (Lutz & Neiva) (Diptera: Psychodidae). Neotrop Entomol. 2008;37:597–601.

Demaio J, Pumpuni CB, Kent M, Beier JC. The midgut bacterial flora of wild Äedes triseriatus, Culex pipiens and Psorophora columbiae mosquitoes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:219–23.

Kokoza V, Ahmed A, Shin SW, Okafor N, Zou Z, Raikhel AS. Blocking of Plasmodium transmission by cooperative action of cecropin a and defensin a in transgenic Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:8111–6. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1003056107.

Wang S, Jacobs-Lorena M. Genetic approaches to interfere with malaria transmission by vector mosquitoes. Trends Biotechnol. 2013;31(3):185–93.

Vega-Rodríguez J, Ghosh AK, Kanzok SM, Dinglasan RR, Wang S, Bongio NJ, et al. Multiple pathways for Plasmodium ookinete invasion of the mosquito midgut. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;111(4):E492-500.

Dillon RJ, El Kordy E, Lanee RP. The prevalence of a microbiota in the digestive tract of Phlebotomus papatasi. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1996;90:669–73.

Azambuja P, Feder D, Garcia ES. Isolation of Serratia marcescens in the midgut of Rhodnius prolixus: impact on the establishment of the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi in the vector. Exp Parasitol. 2004;107:89–96.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Prof. Marcelo Jacob-Lorena of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology, Malaria Research Institute, Baltimore, MD, USA for the gift of the PDB47-Scorpine-HasA and PDB47-HasA plasmids and P. berghei ANKA strain clone 2.34. We thank Mohammad Reza Abai (manager of Culicidae insectarium) and Fatemeh Mohtarami (manager of Molecular Biotechnology Laboratory) in the Department of Medical Entomology and Vector Control, School of Public Health (SPH), Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS). Also, we thank Ms. Talaei (Central Laboratory of SPH, TUMS) and Ms. Salimi (Department of Medical Parasitology, SPH, TUMS) for helping us with the fluorescent microscopy, and Fatimah Rafie (Department of Medical Entomology and Vector Control, SPH, TUMS) for mosquito rearing. We also thanks Mrs Elahe Asiaee from National Institute of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology, Tehran, Iran for helping us with the laboratory work. We are grateful to Miranda Thomas from ICGEB for her insightful suggestions and careful editing of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Elite Researcher Grant Committee under grant number 943677 from the National Institutes for Medical Research Development (NIMAD), Tehran, Iran. This study was also supported by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran (Grant number: 26231).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HD: design, conceptualization, methodology, carrying out of project and writing original draft. MAO: supervision, design of the study, writing, review and editing, interpretation of data, revising the final manuscript, funding acquisition and resources. SHMK: formal analysis and supervisor of project. BY: genetic manipulation of bacteria and formal analysis. NM: methodology and revision of the manuscript. HV: formal analysis and data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All protocols were reviewed and approved by the Ethical Board of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Dataset S1.

Sequences of bicistronic defensin plus green fluorescent protein (DG) construct, including the EcoRI restriction site: GATTC,—35: TTCAA (red and italic),—10: GAGACA (red and italic), ribosomal binding site number 1 (RBS1): AAAAG, signal peptide (sequences 85–135), defensin (sequences 154–309), RBS2: GAAGGAG, GFP: 305–1069, Pst1 restriction site: CTGCAG. Restriction sites at the beginning and end of sequences are capitalized and RBSs are underlined. Defensin and GFP are shown by cyan and green color respectively. The construct verification was performed using the following primers: forward primer DGFP1 (5’-GGA ATT CAA ATA CAT TCA AAT ATG TAT CCG-3’) and reverse primer DGFP7 (5’-TTC TGC AGT TAT TAT TTG TAT AGT TCA TCC ATG-3’).

Additional file 2: Fig. S1.

Digestion of recombinant pBR322 containing Defensin-GFP construct (pBR/DG) and intact pBR322 plasmids with EcoRI and Pst1 restriction enzymes. M: molecular weight marker, 1: pBR/DG, 2: intact type.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Dehghan, H., Mosa-Kazemi, S.H., Yakhchali, B. et al. Evaluation of anti-malaria potency of wild and genetically modified Enterobacter cloacae expressing effector proteins in Anopheles stephensi. Parasites Vectors 15, 63 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-022-05183-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-022-05183-0