Abstract

Background

Chloroquine (CQ) was the cornerstone of anti-malarial treatment in Africa for almost 50 years, but has been widely withdrawn due to the emergence and spread of resistance. Recent reports have suggested that CQ-susceptibility may return following the cessation of CQ usage. Here, we monitor CQ sensitivity and determine the prevalence of genetic polymorphisms in the CQ resistance transporter gene (pfcrt) of Plasmodium falciparum isolates recently imported from Africa to China.

Methods

Blood samples were collected from falciparum malaria patients returning to China from various countries in Africa. Isolates were tested for their sensitivity to CQ using the SYBR Green I test ex vivo, and for a subset of samples, in vitro following culture adaptation. Mutations at positions 72–76 and codon 220 of the pfcrt gene were analyzed by sequencing and confirmed by PCR-RFLP. Correlations between drug sensitivity and pfcrt polymorphisms were investigated.

Results

Of 32 culture adapted isolates assayed, 17 (53.1%), 6 (18.8%) and 9 (28.1%) were classified as sensitive, moderately resistant, and highly resistant, respectively. In vitro CQ susceptibility was related to point mutations in the pfcrt gene, the results indicating a strong association between pfcrt genotype and drug sensitivity. A total of 292 isolates were typed at the pfcrt locus, and the prevalence of the wild type (CQ sensitive) haplotype CVMNK in isolates from East, South, North, West and Central Africa were 91.4%, 80.0%, 73.3%, 53.3% and 51.7%, respectively. The only mutant haplotype observed was CVIET, and this was almost always linked to an additional mutation at A220S.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that a reduction in drug pressure following withdrawal of CQ as a first-line drug may lead to a resurgence in CQ sensitive parasites. The prevalence of wild-type pfcrt CQ sensitive parasites from East, South and North Africa was higher than from the West and Central areas, but this varied greatly between countries. Further surveillance is required to assess whether the prevalence of CQ resistant parasites will continue to decrease in the absence of widespread CQ usage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Among the five species of Plasmodium that cause malaria in humans, Plasmodium falciparum is the most prevalent and virulent, causing high levels of mortality and morbidity worldwide, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. At present, malaria control relies on antiparasitic drugs and anti-mosquito measures. However, the emergence, selection and spread of drug-resistant P. falciparum threatens malaria control and elimination efforts, and there is a growing concern that resistance against the most effective drug currently available, artemisinin and its derivatives, is emerging [1]. In order to control malaria, it is important to prolong the life span of the drugs currently used against the disease.

Chloroquine (CQ), was the most frequently used first-line therapy for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria from the 1940s through to the 2000s due to its high efficacy, safety and low cost [2]. Resistance to CQ was first identified on the Thai-Cambodian border in the late 1950s, concomitantly in South America, and in Africa in the 1970s [3,4,5]. The spread of chloroquine resistance has led to the promotion of sulfadoxine-pyrimethmine (SP) and artemisinin-based combination therapies as first-line treatments for uncomplicated malaria [6, 7]. The associated reduction in CQ use has been linked to the return of CQ susceptibility in several malaria-endemic countries [8]. It has been argued that the cessation of the use of CQ until sensitive parasites reemerge may allow the drug to be reintroduced in these areas [9]. In order to determine whether resistant parasites are disappearing from areas in the absence of CQ use, molecular markers of resistance must be assayed from these populations.

Although the emergence of spread of CQ resistance has multi-factorial causes, it is known that mutations in the P. falciparum CQ resistance transporter gene (pfcrt), are important for the parasite’s acquisition of resistance. A single nucleotide mutation which results in change from lysine to threonine at position 76 of the PfCRT protein is known to confer CQ resistance (CQR), and is the most reliable molecular marker for its presence [10,11,12]. The K76T mutation acts in conjunction with other mutations [13, 14]; codons 74, 75, 220, 271, 326 and 371 have also been shown to play a role in in vitro CQ-resistance [11, 15, 16].

In China, while the number of autochthonous cases has recently declined, there has been a steady increase in the numbers of cases of imported malaria, the majority of which occur in returning laborers. This has become a major challenge for malaria elimination in China [17]. These cases are mainly acquired from African countries, and P. falciparum is the most common species. To inform current and future guidelines on antimalarial use in China, and also African countries, we conducted a CQ sensitivity study and a survey of pfcrt haplotypes in imported P. falciparum isolates from African countries.

Methods

Parasite samples and DNA extraction

This study was carried out in Jiangsu Province, China, where only imported malaria cases have been reported in recent years. Blood samples were collected from 2012 to 2014 from malaria patients with uncomplicated P. falciparum infections at local hospitals or centers for disease control and prevention in Jiangsu Province. Malaria infection was initially diagnosed by microscopy of Giemsa’s solution-stained thick and thin blood smears. Upon confirmation of P. falciparum, 2 ml of venous blood was obtained from each patient by venipuncture into a heparinized tube, blood was stored at 37 °C and transported to the laboratory for in vitro adaptation within 24 h of collection. Blood filter papers from each patient were also prepared, and stored individually after being air dried for later analyses. Genomic DNA was extracted from venous blood samples and filter papers using QIAamp DNA blood kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Malaria parasite species identification was carried out by nested PCR as previously described [18]. Only samples confirmed as mono-infections of P. falciparum were included in this study.

In vitro adaptation of parasites and chloroquine susceptibility assay

Parasites were adapted to continuous culture immediately upon receipt of blood from patients. Blood samples were treated as described previously [19], except that a non-woven fabric (NWF) filter was used to remove leukocytes [20]. Samples were suspended at a 2% hematocrit in complete medium with HEPES (5.94 g/l), hypoxanthine (50 mg/l), Albumax I (5 g/l), RPMI 1640 (10.4 g/l), gentamicin (5 mg/l), and NaHCO3 (2.1 g/l). The mixture was incubated in a tri-gas incubator (containing 5% CO2, 5% O2, and 90% N2) at 37 °C. Routine culture of the parasites was maintained with type O+ RBCs.

Only samples from patients with parasitaemias ≥ 1%, who had not received antimalarial treatment in the preceding three weeks, and when blood samples were transported to the lab within four hours were chosen for ex vivo drug assays. All samples were selected for drug assay after in vitro adaptation, which involved four to five weeks of continuous culture, on average.

The CQ susceptibility of P. falciparum isolates was measured using the World Health Organization protocol [21], with some minor modifications. Chloroquine diphosphate (molecular weight [MW], 515.9; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was prepared by dilution with distilled water, and further diluted with 70% ethanol to achieve a concentration series of 12.5–800 nM in a 96-well culture plate as described previously [22]. This pre-dosed plate was dried, sealed, and stored at 4 °C for up to three months. One hundred microliters of synchronized ring-stage parasite suspension were dispensed into triplicate wells of a pre-dosed CQ plate to obtain a 2% hematocrit and 0.5–1.0% parasitemia. The plates were shaken for 5 min and incubated in a candle jar at 37 °C for 72 h. Chloroquine effectiveness was measured by the SYBR green I-based fluorescence assay [23]. The laboratory clone 3D7 and K1 were included throughout the study as controls.

Analysis of genetic polymorphisms in the pfcrt gene

Polymorphisms in codons 72 to 76 and codon 220 of the pfcrt gene were determined using PCR and sequencing as described previously with minor adjustment [24]. The two fragments, which span codons 44–177 and 181–222 of pfcrt, were amplified by nested PCR assays. Amplified DNA was purified using NucleoSpin® Extract II Kits (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) according to the manual, and sequenced using an ABI PRISM®310 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Sequences were aligned and analyzed using Lasergene software (DNASTAR, Madison, WI, USA). Prior to sequencing, PCR products were cloned into the pGEM-T easy vector (Promega, Madison, USA), and plasmids prepared using the Wizard Plus SV Minipreps DNA purification system (Promega). In addition, genotyping of pfcrt K76T by PCR-RFLP was performed for a subset of samples as described by Schneider et al. [25].

Data analysis

Sequences of pfcrt were aligned and analyzed using Lasergene software. A geographical map of pfcrt haplotypes was produced using SmartDraw software. The geometric mean of the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50), and the 95% confidence interval (CI) were determined using GraphPad Prism 5.0 for Windows. All other statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 for Windows. Differences in IC50 between K76 and 76T were tested using Wilcoxon rank sum test for two independent samples. Differences in IC50 between in vitro testing and the ex vivo test were tested using Wilcoxon signed rank test for paired samples. Mutation rates in different years were compared by Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. All tests were two-sided, P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Parasite samples collection

From 2011 to 2014, more than 1000 imported malaria cases were reported in Jiangsu Province, with Plasmodium species identification by nested PCR based on the 18S rRNA gene revealing that 80% were single species P. falciparum infections. Two hundred and ninety-two P. falciparum isolates, of which 29, 87, 113 and 63 were collected in 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014, respectively, were selected for analysis of pfcrt polymorphism, based on the geographical area in which they were contracted. Blood samples were collected from migrant workers returning from 23 African countries (Table 1, Fig. 1). Among them were 35 isolates from six East African countries, 92 isolates from seven West African countries, five isolates from one country in South Africa, 15 isolates from two North African countries and 145 isolates from eight countries in central Africa. In addition, ten isolates were tested for ex vivo CQ sensitivity, 22 parasite isolates, including the latter ten, were culture-adapted and assayed for in vitro susceptibility to CQ using the SYBR green I method. The culture-adapted isolates were from Equatorial Guinea (n = 13 samples), Angola (n = 15), Nigeria (n = 1), Cameroon (n = 1), Sierra Leone (n = 1), and Gabon (n = 1).

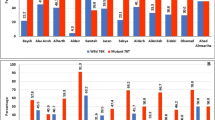

Geographical distribution of pfcrt haplotypes in imported P. falciparum isolates based on amino acid site 76. Circle sizes represent the number of samples from each site. Pie charts presenting the frequencies of the pfcrt haplotypes found in the imported P. falciparum isolates. Wild type = K76; mutant type = 76T; mixed type = K76 + T76

Isolate sensitivity to CQ

Thirty-two culture-adapted isolates with single species P. falciparum infection were collected in 2012 (n = 5), 2013 (n = 21) and 2014 (n = 6). In vitro susceptibilities to CQ were assayed using the SYBR green I method. Based on the criteria described earlier, CQ susceptibility was categorized into three levels: sensitive (S: IC50 < 25 nM); moderately resistant (MR: 25 nM ≥ IC50 < 100 nM); and highly resistant (HR: IC50 ≥ 100 nM) [26, 27]. The median IC50 for CQ was 23.6 nM, ranging from 1.0 to 210.5 nM. Despite this wide variation in sensitivity, of the 32 isolates assayed, 17 (53.1%), six (18.8%) and nine (28.1%) isolates were classified as S, MR, and HR, respectively. Of the nine isolates with HR, four were from Angola, three from Equatorial Guinea, one from Gabon and one from Cameroon. In addition, ten samples were selected for ex vivo testing. Compared to the in vitro test, there was no significant differences in mean IC50s between them (Z = -0.357, P = 0.720); nine of these were consistent with the in vitro testing, however, the IC50 of one isolate was 20.4 nM by the ex vivo test, and 133.0 nM by the in vitro test (Table 2). Compared to the values of the laboratory clone 3D7 and Dd2, the IC50 of six isolates were lower than 3D7, and two isolates were higher than Dd2.

Polymorphisms in the pfcrt gene

Polymorphisms in the pfcrt gene of parasites collected from all enrolled patients were analyzed successfully, with our assay covering codons 72–76 and 220 (Table 1). When mixed infections were excluded, mutations at codons 72–76 were found to be consistent with that at codon 220. The wild type haplotype C72V73M74N75K76 (58.6%) and A220 (57.9%) was the most common, followed by the mutant type C72V73I74E75T76 (34.2%) and S220 (31.8%), and others were mixed haplotypes, such as C72V73M74N75K76+ C72V73I74E75T76 (7.2%) and/or A220 + S220 (10.3%). The CVMNK haplotype was predominant in isolates from East, South and North Africa (91.4, 80.0 and 73.3%, respectively); however, its prevalence was markedly lower in West and Central Africa (53.3 and 51.7%, respectively). A higher number of mixed genotypes were found in isolates from West and Central Africa compared to elsewhere on the continent. In addition, culture-adapted parasite isolates were subject to additional sequencing of the pfcrt locus, the results being consistent with the original, except in the case of one isolate initially typed as a “mixed genotype”, which was found to be a pure mutant type following continuous culture adaptation. The results of the PCR-RFLP assay were entirely consistent with DNA sequencing.

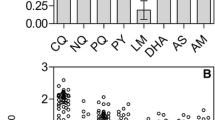

Correlation between polymorphisms in the pfcrt gene and in vitro sensitivity of parasite isolates to CQ

As the pfcrt K76T and A220S mutations were highly prevalent, with only a single mutant haplotype present at codons 72–76, isolates were separated into two groups, wild type (wt) and mutant type (mut) prior to in vitro drug testing (Fig. 2). There were significant differences in mean IC50s between the two groups (Z = -4.27, P < 0.001), the value of mut group being significantly higher than the wt group. In the single isolate which displayed reduced sensitivity to CQ after culture adaptation, there appeared to be a change from a mixed WT/mutant haplotype at pfcrt to a pure mutant haplotype following culture adaptation. Of the ten isolates with drug resistance associated mutations in pfcrt, two were classified as MR and eight as HR. However, the IC50s of isolates with wild type pfcrt, 17 were classified as S, four as MR and one as HR.

Comparison of current pfcrt K76T prevalence with previously published data

Due to its rapid decline in efficiency, CQ was withdrawn as the first-line treatment for P. falciparum malaria from the majority of Africa between 1998 and 2008. The prevalence of the pfcrt K76T mutation in isolates typed in this study was compared with previously reported prevalence recorded after the official withdrawal of CQ from most of Africa. On the whole, the frequency of the CQ-resistant pfcrt 76T has decreased through time, although CQ sensitivity recovery trends show regional variability. Table 3 summarizes the changes in the prevalence of pfcrt 76T–carrying isolates after cessation of CQ use in five African countries, including Angola [28, 29], Congo [29,30,31], Equatorial Guinea [29, 32,33,34], Ghana [29, 35,36,37] and Nigeria [29, 38, 39] (countries contributing ≥20 isolates in the present study). The prevalence of pfcrt 76T–carrying isolates generally reduces through time, except in Equatorial Guinea, which shows large variation within a similar period [29, 32].

Discussion

In the present study, ex vivo and in vitro CQ sensitivity assays were performed with fresh and culture-adapted isolates of P. falciparum. Although continuous in vitro culture can result in the selection of a subpopulation of parasites, nine of the ten samples assayed by both ex vivo and in vitro tests showed consistent results between them. Therefore, using culture-adapted isolates in in vitro assays, although occasionally misleading in some cases, may be an effective way of monitoring CQ susceptibility, especially in areas with low prevalence of CQ resistance. Chloroquine susceptibility of the 32 isolates assayed could be categorized into three levels, including S (17 isolates), MR (6) and HR (9), but could also be separated into sensitive and resistant categories with the cut-off value being an IC50 of 100 nM. Using this latter criterion, eight of ten isolates carrying the pfcrt K76T mutation was defined as resistant, along with one isolate that was wild type at pfcrt but which displayed a CQ IC50 of 124.8 nM. Additionally, IC50 values did not vary significantly between years of isolation.

To date, mutations in the pfcrt gene are the most reliable molecular markers for CQR. We compared the in vitro CQ susceptibility of 32 isolates with point mutations in the pfcrt gene. Two main haplotypes were found at pfcrt codons 72–76; CVMNK (wt) and CVIET (mut), with the latter haplotype strongly associated with the A220S pfcrt mutation, consistent with previous reports [40, 41]. The IC50s of the majority of isolates carrying the wt haplotype were lower than 50 nM. In contrast, the isolates carrying mutations were higher than 50 nM, and 80% (8/10) were above 100 nM. Interestingly, one fresh clinical isolate was typed as a mixed genotype and was deemed sensitive by ex vivo testing, but switched to a pure mut haplotype and was shown to be CQ resistant following culture adaptation. In addition, one isolate that was wild type at the pfcrt locus had a CQ IC50 of 124.8 nM, which may indicate the influence of factors other than pfcrt haplotype in CQ resistance, and so warrants further study. In summary, our results indicate a strong association between pfcrt genotype and drug sensitivity, and are consistent with previous studies [42].

Due to the widespread occurrence of drug resistance, most African countries withdrew CQ as a first line drug for the treatment of P. falciparum malaria between 1998 and 2008 [2]. Following the withdrawal of CQ, complete or partial reversion to CQS alleles have been reported in some countries, such as Malawi [9, 43] and Tanzania [44]. Consistent with this, all of the isolates from these two countries considered in this work were found to be wild-type at the pfcrt locus. However, in contrast to a recent report from Zambia that found no chloroquine-resistant genotypes in 302 isolates [45], we found one resistant mutant in a total of eight isolates from this country. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo, two neighboring countries in Central Africa, CQ was withdrawn in 2001 and 2006, respectively. We found that the prevalence of the pfcrt mut haplotype was 18.2 and 60% in these two countries, respectively, showing a good correlation between length of time since cessation of CQ use, and the prevalence of pfcrt wt strains.

In the present study, analysis of the pfcrt gene indicated that CQ sensitive parasites were more common in the East, South and North Africa than in the West and Central Africa. Chloroquine resistance was first identified in East Africa in the late 1970s [3, 46], and countries in this region were the first to change their first line treatments from CQ to other antimalarial drugs. South Africa was the first country to recommend artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs). Our results confirm previous observations that a reduction in drug pressure is linked to the return of CQ sensitivity [8]. The prevalence of resistant parasites can vary greatly between closely situated countries, such as Ghana and Liberia in West Africa. Even though CQ was withdrawn from these two countries in 2006, the prevalence of pfcrt mut haplotypes were quite different (10.0 and 92.9%, respectively). Although ACTs were introduced at the same time in these two countries, the partner drug of artemisinin in combination therapies plays an important role in pfcrt mutant selection. In addition, the prevalence of pfcrt 76T isolates showed large variation within Equatorial Guinea between three studies carried out at similar times, of which ours is the latest. This suggests that while CQ resistance may be expected to drop following the removal of selective pressure, other factors can affect parasite population dynamics, and the prevalence of drug resistance parasites can vary greatly between locations [47].

Conclusions

This study confirms that there is strong association between pfcrt haplotype and drug sensitivity, and that reduction in drug pressure may lead to an increase in CQ susceptibility. The prevalence of the pfcrt wild-type haplotype in the East, South and North Africa were higher than in the West and Central areas, but varied greatly between countries. While CQ resistance may be expected to drop after the removal of selective pressure, others factors probably affect this process, casting doubt on whether resistant parasites would ever disappear altogether in the absence of drug pressure.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CQ:

-

Chloroquine

- CQR:

-

Chloroquine resistance

- HR:

-

High resistance

- IC50 :

-

50% inhibitory concentration

- MR:

-

Medium resistance

- mut:

-

Mutant type

- pfcrt :

-

Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter gene

- S:

-

Sensitive

- SP:

-

Sulfadoxine-pyrimethmine

- wt:

-

Wild type

References

Ashley EA, Dhorda M, Fairhurst RM, Amaratunga C, Lim P, Suon S, et al. Spread of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:411–23.

Flegg JA, Metcalf CJ, Gharbi M, Venkatesan M, Shewchuk T, Hopkins Sibley C, Guerin PJ. Trends in antimalarial drug use in Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89:857–65.

Fogh S, Jepsen S, Effersoe P. Chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Kenya. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1979;73:228–9.

Harinasuta T, Suntharasamai P, Viravan C. Chloroquine-resistant falciparum malaria in Thailand. Lancet. 1965;2(7414):657–60.

Young MD, Moore DV. Chloroquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1961;10:317–20.

Lebeaux D, Chauhan A, Rendueles O, Beloin C. From in vitro to in vivo models of bacterial biofilm-related infections. Pathogens. 2013;2(2):288–356.

White NJ. Malaria - time to act. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(19):1956–7.

Frosch AE, Venkatesan M, Laufer MK. Patterns of chloroquine use and resistance in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of household survey and molecular data. Malar J. 2011;10:116.

Frosch AE, Laufer MK, Mathanga DP, Takala-Harrison S, Skarbinski J, Claassen CW, et al. Return of widespread chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium falciparum to Malawi. J Infect Dis. 2014;210(7):1110–4.

Djimde A, Doumbo OK, Cortese JF, Kayentao K, Doumbo S, Diourte Y, et al. A molecular marker for chloroquine-resistant falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(4):257–63.

Fidock DA, Nomura T, Talley AK, Cooper RA, Dzekunov SM, Ferdig MT, et al. Mutations in the P. falciparum digestive vacuole transmembrane protein PfCRT and evidence for their role in chloroquine resistance. Mol Cell. 2000;6(4):861–71.

Valderramos SG, Fidock DA. Transporters involved in resistance to antimalarial drugs. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27(11):594–601.

Mehlotra RK, Fujioka H, Roepe PD, Janneh O, Ursos LM, Jacobs-Lorena V, et al. Evolution of a unique Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine-resistance phenotype in association with pfcrt polymorphism in Papua New Guinea and South America. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(22):12689–94.

Summers RL, Dave A, Dolstra TJ, Bellanca S, Marchetti RV, Nash MN, et al. Diverse mutational pathways converge on saturable chloroquine transport via the malaria parasite's chloroquine resistance transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(17):E1759–67.

Sidhu AB, Verdier-Pinard D, Fidock DA. Chloroquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites conferred by pfcrt mutations. Science. 2002;298(5591):210–3.

Vathsala PG, Pramanik A, Dhanasekaran S, Devi CU, Pillai CR, Subbarao SK, et al. Widespread occurrence of the Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter (Pfcrt) gene haplotype SVMNT in P. falciparum malaria in India. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;70(3):256–9.

Liu Y, Hsiang MS, Zhou H, Wang W, Cao Y, Gosling RD, et al. Malaria in overseas labourers returning to China: an analysis of imported malaria in Jiangsu Province, 2001–2011. Malar J. 2014;13:29.

Snounou G, Singh B. Nested PCR analysis of Plasmodium parasites. Methods Mol Med. 2002;72:189–203.

Lu F, Gao Q, Chotivanich K, Xia H, Cao J, Udomsangpetch R, Cui L, Sattabongkot J. In vitro anti-malarial drug susceptibility of temperate Plasmodium vivax from central China. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85(2):197–201.

Tao ZY, Xia H, Cao J, Gao Q. Development and evaluation of a prototype non-woven fabric filter for purification of malaria-infected blood. Malar J. 2011;10:251.

Kuehn MJ, Kesty NC. Bacterial outer membrane vesicles and the host-pathogen interaction. Genes Dev. 2005;19(22):2645–55.

Lu F, Lim CS, Nam DH, Kim K, Lin K, Kim TS, et al. Genetic polymorphism in pvmdr1 and pvcrt-o genes in relation to in vitro drug susceptibility of Plasmodium vivax isolates from malaria-endemic countries. Acta Trop.2011;117(2):69–75.

Smilkstein M, Sriwilaijaroen N, Kelly JX, Wilairat P, Riscoe M. Simple and inexpensive fluorescence-based technique for high-throughput antimalarial drug screening. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(5):1803–6.

Mittra P, Vinayak S, Chandawat H, Das MK, Singh N, Biswas S, et al. Progressive increase in point mutations associated with chloroquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from India. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(9):1304–12.

Schneider AG, Premji Z, Felger I, Smith T, Abdulla S, Beck HP, Mshinda H. A point mutation in codon 76 of pfcrt of P. falciparum is positively selected for by chloroquine treatment in Tanzania. Infect Genet Evol. 2002;1(3):183–9.

Chaijaroenkul W, Wisedpanichkij R, Na-Bangchang K. Monitoring of in vitro susceptibilities and molecular markers of resistance of Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Thai-Myanmar border to chloroquine, quinine, mefloquine and artesunate. Acta Trop. 2010;113(2):190–4.

Hao M, Jia D, Li Q, He Y, Yuan L, Xu S, et al. In vitro sensitivities of Plasmodium falciparum isolates from the China-Myanmar border to piperaquine and association with polymorphisms in candidate genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(4):1723–9.

Fancony C, Brito M, Gil JP. Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance in Angola. Malar J. 2016;15(1):74.

Zhou RM, Zhang HW, Yang CY, Liu Y, Zhao YL, Li SH, et al. Molecular mutation profile of pfcrt in Plasmodium falciparum isolates imported from Africa in Henan province. Malar J. 2016;15(1):265.

Koukouikila-Koussounda F, Malonga V, Mayengue PI, Ndounga M, Vouvoungui CJ, Ntoumi F. Genetic polymorphism of merozoite surface protein 2 and prevalence of K76T pfcrt mutation in Plasmodium falciparum field isolates from Congolese children with asymptomatic infections. Malar J. 2012;11:105.

Tsumori Y, Ndounga M, Sunahara T, Hayashida N, Inoue M, Nakazawa S, et al. Plasmodium falciparum: differential selection of drug resistance alleles in contiguous urban and peri-urban areas of Brazzaville, Republic of Congo. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e23430.

Li J, Chen J, Xie D, Eyi UM, Matesa RA, Obono MM, et al. Molecular mutation profile of Pfcrt and Pfmdr1 in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;36:552–6.

Mendes C, Salgueiro P, Gonzalez V, Berzosa P, Benito A, do Rosario VE, et al. Genetic diversity and signatures of selection of drug resistance in Plasmodium populations from both human and mosquito hosts in continental Equatorial Guinea. Malar J. 2013;12:114.

Berzosa P, Esteban-Cantos A, Garcia L, Gonzalez V, Navarro M, Fernandez T, et al. Profile of molecular mutations in pfdhfr, pfdhps, pfmdr1, and pfcrt genes of Plasmodium falciparum related to resistance to different anti-malarial drugs in the Bata District (Equatorial Guinea). Malar J. 2017;16(1):28.

Alam MT, de Souza DK, Vinayak S, Griffing SM, Poe AC, Duah NO, et al. Selective sweeps and genetic lineages of Plasmodium falciparum drug-resistant alleles in Ghana. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(2):220–7.

Kwansa-Bentum B, Ayi I, Suzuki T, Otchere J, Kumagai T, Anyan WK, et al. Plasmodium falciparum isolates from southern Ghana exhibit polymorphisms in the SERCA-type PfATPase6 though sensitive to artesunate in vitro. Malar J. 2011;10:187.

Sagara I, Oduro AR, Mulenga M, Dieng Y, Ogutu B, Tiono AB, et al. Efficacy and safety of a combination of azithromycin and chloroquine for the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in two multi-country randomised clinical trials in African adults. Malar J. 2014;13:458.

Ojurongbe O, Ogungbamigbe TO, Fagbenro-Beyioku AF, Fendel R, Kremsner PG, Kun JF. Rapid detection of Pfcrt and Pfmdr1 mutations in Plasmodium falciparum isolates by FRET and in vivo response to chloroquine among children from Osogbo, Nigeria. Malar J. 2007;6:41.

Oladipo OO, Wellington OA, Sutherland CJ. Persistence of chloroquine-resistant haplotypes of Plasmodium falciparum in children with uncomplicated malaria in Lagos, Nigeria, four years after change of chloroquine as first-line antimalarial medicine. Diagn Pathol. 2015;10:41.

Van Tyne D, Dieye B, Valim C, Daniels RF, Sene PD, Lukens AK, et al. Changes in drug sensitivity and anti-malarial drug resistance mutations over time among Plasmodium falciparum parasites in Senegal. Malar J. 2013;12:441.

Wootton JC, Feng X, Ferdig MT, Cooper RA, Mu J, Baruch DI, et al. Genetic diversity and chloroquine selective sweeps in Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2002;418(6895):320–3.

Goswami D, Dhiman S, Rabha B, Kumar D, Baruah I, Sharma DK, Veer V. Pfcrt mutant haplotypes may not correspond with chloroquine resistance. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2014;8(6):768–73.

Laufer MK, Thesing PC, Eddington ND, Masonga R, Dzinjalamala FK, Takala SL, et al. Return of chloroquine antimalarial efficacy in Malawi. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(19):1959–66.

Temu EA, Kimani I, Tuno N, Kawada H, Minjas JN, Takagi M. Monitoring chloroquine resistance using Plasmodium falciparum parasites isolated from wild mosquitoes in Tanzania. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75(6):1182–7.

Mwanza S, Joshi S, Nambozi M, Chileshe J, Malunga P, Kabuya JB, et al. The return of chloroquine-susceptible Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Zambia. Malar J. 2016;15(1):584.

Kihamia CM, Gill HS. Chloroquine-resistant falciparum malaria in semi-immune African Tanzaniana. Lancet. 1982;2(8288):43.

Yang Z, Zhang Z, Sun X, Wan W, Cui L, Zhang X, et al. Molecular analysis of chloroquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum in Yunnan Province, China. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12(9):1051–60.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all patients and their relatives for their participation. We are grateful to the staff of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Jiangsu province for assistance with the isolates collection.

Funding

This study was supported by National Research and Development Plan of China (2016YFC1200500), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81271870, 81601790), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20150001, BK20130114, BK20141101), Science and Technology Plan Projects of The General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China (2016IK146), Jiangsu Provincial Key Research and Development Program (BE2016631), Jiangsu Provincial Department of Science and Technology (BM2015024–1), and Jiangsu Provincial Department of Health (Q201203).

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FL, JC and QG conceived and designed the study; MHZ and FL performed experiments and data analysis; SX, JXT, HYZ, GDZ, YPG, CZ, YBL, WMW, YYC and JLL contributed to sample collection and species identification; FL and MHZ wrote the manuscript. JC, RLC and XLH assisted with the interpretation of the results and manuscript drafting. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all patients. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jiangsu Institute of Parasitic Diseases (IRB00004221), Wuxi, China.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, F., Zhang, M., Culleton, R.L. et al. Return of chloroquine sensitivity to Africa? Surveillance of African Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance through malaria imported to China. Parasites Vectors 10, 355 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-017-2298-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-017-2298-y