Abstract

Background

The viruses transmitted by Aedes aegypti, including dengue and Zika viruses, are rapidly expanding in geographic range and as a threat to public health. In response, control programs are increasingly turning to the use of sterile insect techniques resulting in a need to trap male Ae. aegypti to monitor the efficacy of the intervention. However, there is a lack of effective and cheap methods for trapping males. Thus, we attempted to exploit the physiological need to obtain energy from sugar feeding in order to passively capture male and female Ae. aegypti (nulliparous and gravid) in free-flight attraction assays. Candidate lures included previously identified floral-based (phenylacetaldehyde, linalool oxide, phenylethyl alcohol, and acetophenone) attractants and an attractive toxic sugar bait-based (ATSB) solution of guava and mango nectars. A free-flight attraction assay assessed the number of mosquitoes attracted to each candidate lure displayed individually. Then, a choice test was performed between the best-performing lure and a water control displayed in Gravid Aedes Traps (GAT).

Results

Results from the attraction assays indicated that the ATSB solution of guava and mango nectars was the most promising lure candidate for males; unlike the floral-based attractants tested, it performed significantly better than the water control. Nulliparous and gravid females demonstrated no preference among the lures and water controls indicating a lack of attraction to floral-based attractants and sugar baits in a larger setting. Although the guava-mango ATSB lure was moderately attractive to males when presented directly (i.e. no need to enter a trap or other confinement), it failed to attract significantly more male, nulliparous female, or gravid female Ae. aegypti than water controls when presented inside a Gravid Aedes Trap.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that the use of volatile floral-based attractants and sugar mixtures that have been identified in the literature is not an effective lure by which to kill Ae. aegypti at ATSB stations nor capture them in the GAT. Future trapping efforts would likely be more successful if focused on more promising methods for capturing male and female Ae. aegypti.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The resurgence of once geographically limited vector-borne diseases, particularly those viruses transmitted by mosquitoes such as dengue, Zika and chikungunya viruses, have become an increasingly serious threat to public health in recent years. The expansion of these diseases is largely spurred by anthropogenic activities including increased mobility of human populations, habitat modification, and climate change [1, 2]. In the wake of these changes, vector-borne diseases are moving from one place to another at unprecedented rates, causing progressively more people to be at risk of contracting these diseases [1, 2]. In particular, diseases transmitted by Aedes aegypti, the yellow fever mosquito, have experienced a notable resurgence and expansion in recent years, especially Zika and dengue viruses [3, 4]. In the past year, Zika virus has spread through much of the Western Hemisphere, resulting in a public health emergency due to its likely association with microcephaly, a serious congenital malformation [5–7]. Furthermore, the incidence of dengue has increased 30-fold in the past 50 years. As a result, 2.5 billion people currently live at risk of contracting this disease, and there are 50 million infections and 22,000 deaths per year [3]. The cost of dengue on public health is substantial, including direct costs to local and global health organizations and immense economic and social costs [8, 9].

In response to the threat of dengue in endemic countries (and impending threat in non-endemic countries), scientists have increasingly turned to population level manipulations that rely upon males for optimal efficiency and successful dissemination. For example, the Eliminate Dengue program releases both male and female Ae. aegypti infected with Wolbachia, which reduces the ability of the mosquito to transmit dengue virus [10]. Additionally, biotech companies, such as Oxitec, produce genetically engineered sterile male Ae. aegypti, which suppresses vector population levels [11]. Other male-based sterile insect techniques (SITs), including radiation and feeding with double stranded RNA, also rely upon the release of sterile males for control of Ae. aegypti [12–14]. With the advent of such technologies, it has become increasingly important to trap males, in addition to females (the traditional target of mosquito control programs) in order to monitor the efficacy of these technologies. However, the tools available to sample wild male Ae. aegypti are limited. Those that do exist, such as the Biogents Sentinel Trap (BGS), are prohibitively expensive for large, wide-ranging studies and rely upon energy from batteries or mains power to function [15]. The passive trap options available for the capture of female Ae. aegypti, such as the Gravid Aedes Trap (GAT) and autocidal gravid ovitrap, are more practical and affordable [16–18]. These traps mimic the ecological drivers of oviposition site selection, such as dark color and odor of fermented plant material, in order to lure gravid females into the trap to lay eggs. Naturally, this technique is not effective for male Ae. aegypti, so passive trap designs must rely upon other physiological needs pertinent to male survival, such as sugar-feeding. Both male and female Ae. aegypti acquire energy in the form of carbohydrates from plants. This is the only source of food for males, as opposed to females, which primarily derive energy from blood meals [19].

Anopheles control programs have already successfully implemented strategies that exploit the sugar-feeding behavior of mosquitoes in the form of attractive toxic sugar baits (ATSB) [20–22]. Attractive toxic sugar baits strategies use floral-based attractants from a flower or fruit to attract the mosquitoes, include sugar to induce feeding, and an oral toxin to kill the mosquitoes. The technique has resulted in substantial reductions in the mosquito populations at the sites where it has been tested [20–23]. Aedes albopictus control programs have also had similar success with ATSB [24–26].

This same physiological need could be harnessed in order to trap Ae. aegypti. Several floral-based attractants, including acetophenone and phenylacetaldehyde, have been shown to be attractive to Ae. aegypti in small scale experiments [27, 28]. In the discussion of each of these papers, the authors highlighted the potential to use the promising floral-based compounds identified as attractants in traps [27, 28]. Additionally, ATSB of guava-mango nectars has been successful in reducing Ae. albopictus populations [25], which is an attraction that may extend to Ae. aegypti due to the biological and ecological similarities between Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus [29]. Thus, the objective of this study was to assess the attraction and potential to capture male and female (nulliparious and gravid) Ae. aegypti using promising floral-based attractants, ATSB solutions, and combinations of both. Candidate lures were assessed in free-flight tent trials to determine if preliminary reports from previously published small-scale trials were indicative of success in larger settings. If successful, using ATSBs to passively capture male and female Ae. aegypti would enable the creation of a practical and economically viable trap to monitor and aid control programs, especially SIT programs.

Methods

Aedes aegypti colony

Mosquitoes used in the studies were from a colony established from eggs collected in ovitraps in Cairns (QLD, Australia) and were periodically supplemented with wild collections to maintain genetic vigor. Mosquito larvae were reared on fish food powder (TetraMin Rich Mix, Tetra Melle, Germany). Adults were fed on a 50% honey solution and were blood-fed 3 times per week using human volunteers (Human ethics approval from James Cook University H3555). Mosquitoes between one and two weeks old were starved overnight prior to use in trials (about 18 h).

Lure selection and presentation

General lure selection and presentation

Based on the literature and preliminary comparisons, five potential lures were chosen including three volatile floral-based attractants compound lures, one sugar lure and one combination combining floral attractants and sugar lure (Table 1). The three floral-based attractants were presented on a 3 × 3 cm sponge soaked in 12 ml of distilled water in volumes of 200 μl for phenylacetaldehyde, 200 μl for acetophenone, and a combination of 50 μl each of phenylacetaldehyde, linalool oxide, phenylethyl alcohol and acetophenone. An ATSB lure was created based on a recent recipe shown to be highly attractive to Ae. albopictus [25]. Initial sugar lure preparation involved the mixing of 0.2 l of guava nectar (Golden Circle), 0.2 l of mango nectar (Golden Circle), 0.2 l of distilled water and 200 g of brown sugar in an Erlenmeyer flask over heat using a heating pad and magnetic stirrer. When the sugar was fully suspended, the mixture was poured into a plastic container and allowed to cool and ferment for 24 h at room temperature. This mixture is referred to as guava-mango through the remainder of the paper. For each trial, 12 ml of guava-mango was pipetted onto a sponge for presentation. A combination lure of guava-mango and phenylacetaldehyde was also created by soaking the sponge with 12 ml of guava-mango and 200 μl of phenylacetaldehyde. All lures were displayed on a piece of sponge that was previously soaked in a 1% sodium hypochlorite (Chlorox®, Oakland, CA, USA) solution to dispel the chemicals used for packaging, after which the sponge was thoroughly rinsed and dried. The same procedure is used to sugar-feed the mosquitoes with 50% honey solution for lab-rearing.

Development and validation of blue dye and fipronil to assess sugar-feeding

To assess sugar-feeding we incorporated blue food dye and the insecticide fipronil (0.06% by volume, Termidor®, Victoria, Australia) [30–32] in our control (distilled water) and treatment solutions (floral-based attractants and sugar lures) to knock down mosquitoes that ingested the lure and provide a visible blue dye in the abdomen (Fig. 1) to indicate that death was caused by ingestion and not natural causes. The rationale was that a larger number of Ae. aegypti dead after 24 h would mean that a larger number of mosquitoes ingested the lure from the sponge, which would suggest that the mosquitoes were more attracted to that lure.

The time to death or incapacitation after ingesting fipronil was determined by aspirating 13 male Ae. aegypti into a rearing cage (Bioquip Bug Dorms; 30 × 30 × 30 cm) with 12 ml of guava-mango treated with blue dye and fipronil and observing the number of landings on the sponge and the number of knock-down mosquitoes over two hours. We tested if mosquitoes readily fed on fipronil-treated lures by aspirating 20 male Ae. aegypti into two buckets with mesh covering. The treatment bucket contained a sponge with 12 ml of guava-mango treated with blue dye and fipronil while the control bucket contained a sponge with 12 ml of guava-mango treated only with blue dye. The number of mosquitoes in the treatment bucket that were killed and had visible blue in their abdomen was counted. The number of live mosquitoes in the control bucket was counted and then frozen so that the number with visible blue in the abdomen could be counted. The number that ingested the guava-mango was compared between treatment and control to see if there was any aversion to the fipronil treatment. The same procedure was repeated with 13 females.

Are Ae. aegypti attracted to floral-based attractants and sugar lures?

For the attraction assay, we set up six tents (3.24 m3, Wild Country, Alfreton, United Kingdom) in a temperature and humidity controlled semi-field cage. The temperature and humidity in the semi-field cage track those of the outdoors, reflecting normal conditions in Cairns, Australia between June and August. The mean daily high temperature for June, July and August was 26.8 °C, 25.9 °C, and 27.1 °C, respectively, and the mean daily low temperature was 20.1 °C, 17.4 °C, and 16.6 °C, respectively [33]. The floors of the tents were covered with white tarp so that the dead mosquitoes would be easily spotted for counting. An overturned black plastic bucket from a Gravid Aedes Trap (GAT) [16] was placed at the middle of each tent to attract and induce swarming by male mosquitoes and provide a resting site for females. A small dish with the lure-treated sponges was placed on top of each GAT bottom. This feature was added after preliminary trials showed very little interaction with the sponge in the absence of a swarm marker or resting site.

We released 20 male Ae. aegypti into each tent after starving them overnight (about 18 h). They were left in the tent for 24 h, after which the dead mosquitoes on the ground of the tent were counted and inspected under a stereo microscope for blue dye in the abdomen or crop. The number with visible blue dye was noted, as this was considered the number definitively killed by the fipronil-treated attractant or control. The remaining live mosquitoes were cleaned from the tent using a Prokopak aspirator [34]. This procedure was repeated five times, for a total of five replications. The tent in which each of the five different treatments and the control were placed for each replication was randomized using the random number generator random.org. The same procedure was used with 20 nulliparous females as well as with 20 gravid female Ae. aegypti. The gravid females were blood fed six to seven days prior to use. Both the nulliparous and gravid females were starved overnight before use in the trials.

Can the guava-mango lure be used to trap Ae. aegypti in the GAT?

Choice test between guava-mango lure and water control

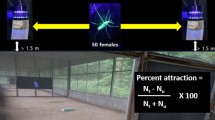

The attraction assays indicated that the ATSB guava-mango solution was the most attractive lure for male Ae. aegypti, so a secondary experiment was conducted to assess the potential to use this attraction to capture mosquitoes in the GAT. The guava-mango lure was prepared in the same way as in the attraction assay preparation, however the blue dye and fipronil were not added. The same six tents described for the attraction assay were used for the choice test. Each tent had two GATs set up at opposite corners across a diagonal (Fig. 2). The GATs were ~ 1/5 filled with tap water and five alfalfa pellets. Insecticide-treated bed net (5% alphacypermethrin) was placed over the screens of the GAT heads in order to knock down any mosquitoes that entered the traps. Each GAT was placed on a circular tray covered with talcum powder to prevent ants from entering the trap. In each tent, one GAT was the control, with a sponge soaked in 12 ml of distilled water in a plastic dish. The other GAT was the treatment, with a sponge soaked in 12 ml of the guava-mango lure in a plastic dish. In order to control for placement bias, the placement of the control and treatment GATs was switched in every other tent. Therefore, three of the tents had the guava-mango GAT in the far left corner and three had the guava-mango GAT in the near right corner, while the control GAT was at the other side of the diagonal in each tent. Twenty male Ae. aegypti were released into each tent and left for three nights (about 72 h). Thereafter, we removed the GATs from the tents and counted the number of mosquitoes in each. The same procedure was repeated with four tents over a separate 72 h for a total of 10 replicates. The procedure was also repeated with 20 nulliparous females and with 20 gravid female Ae. aegypti. Six replicates were conducted for each of these experiments using the six tents over one 72 h period in both cases.

Image of tent and diagram of experimental setup. a Picture of tent with treatment and control GAT. b Diagram of experimental setup in the semi field cage. The grey squares represent the floor of the tents, the black circles represent the GATs treated with guava-mango and the white circles represent the control GATs

Larger scale choice test

In a separate experiment, we increased the amount of liquid presented in each GAT. We scaled it up ten-fold from 12 ml to 120 ml to see if larger quantities would improve results. A full sponge was placed in a larger dish in the treatment and control GATs in order to absorb the increased quantity of guava-mango and water respectively. This was conducted in the six tents over a 72 h period for a total of six replicates. The same procedure was followed as described for the 12 ml paired test. However, this larger scale version was only conducted with male mosquitoes (20 male Ae. aegypti per tent).

Statistical analysis

Analysis was conducted using SAS Studio 3.5. All data sets were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk, test. Due to non-normality in all of the datasets, Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare the number of mosquitoes killed among the treatments and controls in the attraction assays. Due to non-normality in the male dataset, non-parametric Wilcoxon signed rank tests for paired samples were used to compare the number of mosquitoes captured by the sugar lure (guava-mango) and control GATs in the choice test.

Results

Validation of blue dye and fipronil to assess sugar-feeding

The observation of 13 male Ae. aegypti in a rearing cage with fipronil-treated guava-mango lure showed that those males that ingested the lure were knocked down within two hours of exposure. This shows the quick lethal action of the insecticide in Ae. aegypti. The comparison of 18 males fed with fipronil-treated guava-mango juice versus 19 males fed with insecticide-free guava-mango juice demonstrated that there is no aversion to fipronil. All 18 of the mosquitoes in the fipronil-treated bucket died, whereas none of the 17 mosquitoes in the untreated control died. Additionally, 15 of the 18 males in the fipronil-treated bucket had a visibly blue abdomen, which indicated substantial consumption of the guava-mango juice due to the blue food dye. In the untreated bucket, all 19 males had a visibly blue abdomen. The same comparison was repeated with 13 females in the bucket with fipronil-treated guava-mango juice and 13 females in the bucket with untreated guava-mango juice. The fipronil-treated bucket resulted in 13 dead mosquitoes, all with a blue abdomen. The untreated bucket resulted in 13 live mosquitoes, all with blue abdomen.

Attraction assays

Male response to attraction assay

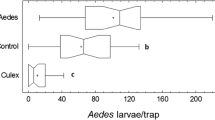

To measure the efficacy of each lure, we measured the number of mosquitoes dead and the number of mosquitoes with blue coloration in the abdomen after 18 h (Fig. 3a, Table 2). The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was significant (χ 2 (5,5) = 14.73, P = 0.01), indicating that one of the lures performed significantly differently from the other lures and the control. The guava-mango lure attracted and killed the highest mean number of male Ae. aegypti and performed particularly well in a couple of replicates (Additional file 1: Table S1), with 13.0 ± 8.2% of released males observed dead with indication of ingestion of the lure (Table 2, Fig. 3a).

Percent of Ae. aegypti killed and captured in the attraction assay and choice test. a The percent of total number of mosquitoes released found dead with blue abdomens for each treatment in the attraction assays (n = 5). b The percent of total number of mosquitoes released caught in GATs baited with the guava-mango lure or water controls over a 72 h period. All experiments used 12 ml of guava-mango and control solution except one in which 120 ml of solution was used to assess the effect of dosage. For both experiments 20 mosquitoes were released during each replicate with a minimum of five replicates being completed for each of the lures and control. Different letters indicate significant differences among the treatments (P < 0.05)

Female response to attraction assay

No significant difference in attractiveness was observed among the treatments and controls as indicated by the number of nulliparous (χ 2 (5,5) = 4.14, P = 0.53) and gravid (χ 2 (5,5) = 8.92, P = 0.11) females with blue-colored abdomens (Table 2, Fig. 3a).

Choice test between guava-mango lure and water control

Male response

When compared directly to a water control, the guava-mango lure was not successful in attracting male Ae. aegypti into the GAT (Table 3, Fig. 3b). Overall, a mean (± SE) percentage of released male Ae. aegypti that entered and died in the GAT baited with guava-mango lure was 19.5 ± 4.5% after 10 replicates, whereas a mean of 32.0 ± 5.2% of released males entered and died in the GAT baited with water control (Fig. 3b). Analysis showed that the preference for the control over the guava-mango lure was significant (Z = 2.22, P = 0.03).

Nulliparous females

The guava-mango lure was not successful in attracting nulliparous female Ae. aegypti into the GAT (Table 3, Fig. 3b). The mean (± SE) percentage of female Ae. aegypti that entered and died in the GAT baited with guava-mango or the control lure was 26.7 ± 8.8% and 32.5 ± 9.9%, respectively. There was no significant difference between the guava-mango and the control (Z = 0.16, P = 0.87).

Gravid females

The guava-mango lure was not successful in attracting gravid female Ae. aegypti into the GAT (Table 3, Fig. 3b). The mean percentage of gravid female Ae. aegypti that entered and died was 38.3 ± 7.5% in the GAT treated with guava-mango lure and 45.8 ± 6.5% in the control GAT. There was no significant difference between guava-mango and control (Z = 0.73, P = 0.47).

Larger scale lure

When the amount of guava-mango lure was increased by ten times the volume, it was still not successful in attracting male Ae. aegypti into the GAT (Table 3, Fig. 3b). The mean percentage of released male Ae. aegypti that entered and died was 35.8 ± 9.1% in the GAT treated with guava-mango lure and 27.5 ± 5.6% in the control GAT. Analysis showed that there was no significant difference between the capture of the guava-mango and control GATs (Z = -0.40, P = 0.69).

Discussion

The floral-based attractants and ATSB lures reported as attractive to Aedes mosquitoes did not attract male Ae. aegypti, nor females regardless of physiological status (i.e. gravid or nulliparous) when presented in larger enclosures (tents) more reflective of field conditions. In the attraction assay, the guava-mango ATSB attracted significantly more males than the other four lures and the control, however the average percentage of mosquitoes killed was low (13 ± 8.2%), indicating that it would be an inefficient attractant. Nonetheless, the guava-mango lure performed particularly well in a couple of replicates, killing more mosquitoes than observed in any of the replicates of the other lures and control (Additional file 1: Tables S1, S2, S3). Since the main interest of the study was to find a lure that could successfully trap males for control and monitoring purposes, we proceeded with the most promising lure among the male trials. The next step was to bait a GAT with the guava-mango lure and pair it with a water control to compare the number of Ae. aegypti captured in each. The guava-mango GAT did not capture significantly more male, nulliparous or gravid female Ae. aegypti than the control GAT.

These results were unexpected because the bulk of the pre-existing literature suggested that male Ae. aegypti rely upon plant sugars to satisfy their energetic requirements [19]. Additionally, previous studies identified specific floral-based attractants that are particularly attractive to Ae. aegypti in small-scale enclosures and olfactometer studies under laboratory conditions. Furthermore, a sugar lure was identified as a successful attractant for Ae. albopictus in ATSB field studies [25]. The existing evidence therefore suggested that these floral-based attractants and sugar lures would be attractive to Ae. aegypti on a larger spatial scale and may facilitate passive trapping of males and females. However, once tested, this was not the case.

Despite the widespread acceptance that Ae. aegypti, especially males, derive energy from flower nectar [19], there is a growing body of evidence that the extent of this behavior is limited, especially among females [35, 36]. A mark-release-recapture study in Thailand showed that females in the field did not consume sugar over a two to three day period. In the same study, only one third of male Ae. aegypti consumed sugar [36]. Furthermore, there is evidence that suggests that in females, sugar feeding may be detrimental to survival when compared to blood feeding alone [37]. The conclusions reached in the aforementioned papers support the conclusion of our study, that the impetus to sugar feed is not strong enough to merit the basis of a lure for passive trapping. One of the reasons why Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti may differ in their readiness to sugar feed is how Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus interact with and rely upon vegetation. For example, Ae. albopictus tends to thrive in more highly vegetated habitats with a presumably high density of natural sugar sources, whereas Ae. aegypti prefers urbanized landscapes, often harboring inside houses and buildings, with presumably lower densities of natural sugar sources [38, 39]. These differences in habitat preference may have selected for a greater attraction to natural floral sugar sources in Ae. albopictus than Ae. aegypti and may account for the inconsistent attraction to the ATSB lure among Ae. aegypti.

Our findings suggest that it is inefficient to use these floral-based attractants and sugar lures in ATSB stations for the control of Ae. aegypti populations. The results also indicate that it is ineffective to use these lures to target sugar-feeding behavior in order to trap male and female Ae. aegypti passively. In contrast, recent research has shown that sound lures mimicking the tone of the female wing beat frequency provide a highly effective mechanism to trap male Ae. aegypti passively [40]. This may be a promising alternative to the lures investigated in this study for the capture of male Ae. aegypti. As for females, the use of simple gravid traps, such as the CDC Autocidal Gravid Trap and GAT [41, 42], and the use of BG-Sentinel traps (with and without CO2) are effective means of sampling gravid and nulliparious female Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus [43, 44].

Conclusions

The attraction assay demonstrated that the floral-based attractants and sugar mixtures previously identified in the literature as potential trap lures were not more attractive than water to female (nulliparous and gravid) Ae. aegypti. The most promising of these lures for males, a combination of guava and mango nectars, did not facilitate passive trapping of the mosquitoes. These data suggest that the use of the volatile floral-based attractants and sugar mixtures that have been identified in the literature is not an effective lure to passively capture male or female Ae. aegypti in the GAT or at ATSB stations. Although our results do not support the use of the floral-based attractants and ATSB baits tested as trap lures, further work is needed that includes other characteristics of natural sugar sources (e.g. structural and color components of natural floral sugar sources) before their utility as attractants can be fully assessed. However, as it stands now, current efforts to trap male Ae. aegypti would likely have improved success if focused on more promising methods.

Abbreviations

- ATSB:

-

Attractive toxic sugar bait

- BGS:

-

Biogent sentinel trap

- GAT:

-

Gravid Aedes trap

- GM:

-

Guava-mango

- Phenyl:

-

Phenylacetaldehyde

- PLPA:

-

Phenylacetaldehyde + linalool oxide + phenylethyl alcohol + acetophenone

- SIT:

-

Sterile insect technique

References

Adams B, Kapan DD. Man bites mosquito: understanding the contribution of human movement to vector-borne disease dynamics. PLoS One. 2009;4(8), e6763.

Patz JA, Reisen WK. Immunology, climate change and vector-borne diseases. Trends Immunol. 2001;22(4):171–2.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Dengue. 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/epidemiology/. Accessed 12 Dec 2016.

Kindhauser MK, Allen T, Frank V, Santhana RS, Dye C. Zika: the origin and spread of a mosquito-borne virus. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;171082.

World Health Organization. WHO Director-General summarizes the outcome of the Emergency Committee regarding clusters of microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome. Saudi Med J. 2016;37(3):334.

Messina JP, Kraemer MU, Brady OJ, Pigott DM, Shearer FM, Weiss DJ, et al. Mapping global environmental suitability for Zika virus. eLife. 2016;5, e15272.

Teixeira MG, da Conceição N, Costa M, de Oliveira WK, Nunes ML, Rodrigues LC. The epidemic of Zika virus-related microcephaly in Brazil: Detection, control, etiology, and future scenarios. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):601–5.

Shepard DS, Coudeville L, Halasa YA, Zambrano B, Dayan GH. Economic impact of dengue illness in the Americas. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;84(2):200–7.

Gubler DJ. The economic burden of dengue. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86(5):743–4.

Hoffmann A, Montgomery B, Popovici J, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Johnson P, Muzzi F, et al. Successful establishment of Wolbachia in Aedes populations to suppress dengue transmission. Nature. 2011;476(7361):454–7.

Lacroix R, McKemey AR, Raduan N, Wee LK, Ming WH, Ney TG, et al. Open field release of genetically engineered sterile male Aedes aegypti in Malaysia. PLoS One. 2012;7(8), e42771.

Lees RS, Gilles JR, Hendrichs J, Vreysen MJ, Bourtzis K. Back to the future: the sterile insect technique against mosquito disease vectors. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2015;10:156–62.

Rodriguez SD, Brar RK, Drake LL, Drumm HE, Price DP, Hammond JI, et al. The effect of the radio-protective agents ethanol, trimethylglycine, and beer on survival of X-ray-sterilized male Aedes aegypti. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6(1):1–8.

Whyard S, Erdelyan C, Partridge AL, Singh AD, Beebe NW, Capina R. Silencing the buzz: a new approach to population suppression of mosquitoes by feeding larvae double-stranded RNAs. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:96.

Kroeckel U, Rose A, Eiras ÁE, Geier M. New tools for surveillance of adult yellow fever mosquitoes: comparison of trap catches with human landing rates in an urban environment. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2006;22(2):229–38.

Ritchie SA, Buhagiar TS, Townsend M, Hoffmann A, Van Den Hurk AF, McMahon JL, Eiras AE. Field validation of the gravid Aedes trap (GAT) for collection of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 2014;51(1):210–9.

Mackay AJ, Amador M, Barrera R. An improved autocidal gravid ovitrap for the control and surveillance of Aedes aegypti. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6(1):225.

Eiras AE, Buhagiar TS, Ritchie SA. Development of the gravid Aedes trap for the capture of adult female container-exploiting mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 2014;51(1):200–9.

Foster WA. Mosquito sugar feeding and reproductive energetics. Annu Rev Entomol. 1995;40(1):443–74.

Müller GC, Beier JC, Traore SF, Toure MB, Traore MM, Bah S, et al. Successful field trial of attractive toxic sugar bait (ATSB) plant-spraying methods against malaria vectors in the Anopheles gambiae complex in Mali. West Africa Malar J. 2010;9(1):210.

Müller GC, Schlein Y. Efficacy of toxic sugar baits against adult cistern-dwelling Anopheles claviger. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102(5):480–4.

Müller GC, Kravchenko VD, Schlein Y. Decline of Anopheles sergentii and Aedes caspius populations following presentation of attractive toxic (spinosad) sugar bait stations in an oasis. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2008;24(1):147–9.

Revay EE, Schlein Y, Tsabari O, Kravchenko V, Qualls W, Xue RD, et al. Formulation of attractive toxic sugar bait (ATSB) with safe EPA-exempt substance significantly diminishes the Anopheles sergentii population in a desert oasis. Acta Trop. 2015;150:29–34.

Revay EE, Müller GC, Qualls WA, Kline DL, Naranjo DP, Arheart KL, et al. Control of Aedes albopictus with attractive toxic sugar baits (ATSB) and potential impact on non-target organisms in St. Augustine, Florida. Parasitol Res. 2014;113(1):73–9.

Naranjo DP, Qualls WA, Müller GC, Samson DM, Roque D, Alimi T, et al. Evaluation of boric acid sugar baits against Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in tropical environments. Parasitol Res. 2013;112(4):1583–7.

Xue RD, Kline DL, Ali A, Barnard DR. Application of boric acid baits to plant foliage for adult mosquito control. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2006;22(3):497–500.

Oppen S, Masuh H, Licastro S, Zerba E, Gonzalez-Audino P. A floral‐derived attractant for Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Entomol Exp Appl. 2015;155(3):184–92.

Jhumur US, Dötterl S, Jürgens A. Electrophysiological and behavioural responses of mosquitoes to volatiles of Silene otites (Caryophyllaceae). Arthropod Plant Interact. 2007;1(4):245–54.

Kaplan L, Kendell D, Robertson D, Livdahl T, Khatchikian C. Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in Bermuda: extinction, invasion, invasion and extinction. Biol Invasions. 2010;12(9):3277–88.

Xue RD, Ali A, Kline DL, Barnard DR. Field evaluation of boric acid-and fipronil-based bait stations against adult mosquitoes. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2008;24(3):415–8.

Pridgeon JW, Pereira RM, Becnel JJ, Allan SA, Clark GG, Linthicum KJ. Susceptibility of Aedes aegypti, Culex quinquefasciatus Say, and Anopheles quadrimaculatus Say to 19 pesticides with different modes of action. J Med Entomol. 2008;45(1):82–7.

Ritchie SA, Cortis G, Paton C, Townsend M, Shroyer D, Zborowski P, et al. A simple non-powered passive trap for the collection of mosquitoes for arbovirus surveillance. J Med Entomol. 2013;50(1):185–94.

Cairns Queensland Daily Weather Observations. Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology. http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/dwo/IDCJDW4024.latest.shtml. Accessed 5 May 2016.

Vazquez-Prokopec GM, Galvin WA, Kelly R, Kitron U. A new, cost-effective, battery-powered aspirator for adult mosquito collections. J Med Entomol. 2009;46(6):1256–9.

Spencer CY, Pendergast IV TH, Harrington LC. Fructose variation in the dengue vector, Aedes aegypti, during high and low transmission seasons in the Mae Sot region of Thailand. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2005;21(2):177–81.

Edman JD, Strickman D, Kittayapong P, Scott TW. Female Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) in Thailand rarely feed on sugar. J Med Entomol. 1992;29(6):1035–8.

Harrington LC, Edman JD, Scott TW. Why do female Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) feed preferentially and frequently on human blood? J Med Entomol. 2001;38(3):411–22.

Braks MA, Honório NA, Lourenço-De-Oliveira R, Juliano SA, Lounibos LP. Convergent habitat segregation of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in southeastern Brazil and Florida. J Med Entomol. 2003;40(6):785–94.

Tsuda Y, Suwonkerd W, Chawprom S, Prajakwong S, Takagi M. Different spatial distribution of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus along an urban-rural gradient and the relating environmental factors examined in three villages in northern Thailand. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2006;22(2):222–8.

Johnson BJ, Ritchie SA. The Siren’s song: Exploitation of female flight tones to passively capture male Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 2015;53(1):245–8.

Barrera R, Amador M, Acevedo V, Caban B, Felix G, Mackay AJ. Use of the CDC Autocidal Gravid Ovitrap to control and prevent outbreaks of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 2014;51:145–54.

Johnson BJ, Hurst T, Hung Luu Q, Unlu I, Freebairn C, Faraji A, Ritchie SA. Field comparisons of the Gravid Aedes Trap (GAT) and BG-Sentinel trap for monitoring Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) populations and notes on indoor GAT collections in Vietnam. J Med Entomol. 2016. doi:10.1093/tjw166

Farajollahi A, Kesavaraju B, Price DC, Williams GM, Healy SP, Gaugler R, Nelder MP. Field efficacy of BG-Sentinel and industry-standard traps for Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) and West Nile virus surveillance. J Med Entomol. 2009;46:919–25.

Maciel-de-Freitas R, Eiras AE, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R. Field evaluation of effectiveness of the BG-Sentinel, a new trap for capturing adult Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2006;101:321–5.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jane Lloyd, Chris Paton, Michael Townsend, and Gavin Omodei for their assistance with mosquito rearing.

Funding

This research was funded by the Downs Fellowship of the Yale School of Public Health and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Senior Research Fellowship 1044698.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed during this study are included in the article and its additional file.

Authors’ contributions

KF conducted experiments and drafted the manuscript. BJ and SR provided guidance on experimental design. BJ provided a number of figures for the manuscript. BJ, SR and DF provided key edits and structural reformatting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Summary of data collected in the male attraction assay. The information provided includes treatment type, replicate number, tent site (position in the flight cage), number of dead mosquitoes, number of dead mosquitoes with blue abdomens, and the date of data collection. Table S2. The same information was provided as in Additional file 1: Table S1 for the data collected in the nulliparous female attraction assay. Table S3. The same information was provided as in Additional file 1: Table S1 for the data collected in the gravid female attraction assay. Table S4. Summary of data collected in the male (12 ml) choice test, including the number of males collected in the guava-mango and control GATs. Table S5. Summary of data collected in the nulliparous female choice test, including the number of nulliparous females collected in the guava-mango and control GATs. Table S6. Summary of data collected in the gravid female choice test, including the number of gravid females collected in the guava-mango and control GATs. Table S7. Summary of data collected in the male (120 ml) choice test, including the number of males collected in the guava-mango and control GATs. (XLSX 46 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Fikrig, K., Johnson, B.J., Fish, D. et al. Assessment of synthetic floral-based attractants and sugar baits to capture male and female Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasites Vectors 10, 32 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1946-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1946-y