Abstract

Background

Lake Tanganyika is the world’s second deepest lake. Its diverse cichlid assemblage offers a unique opportunity for studying a deep-water host-parasite model in freshwater. Low host specificity and a broad host range including representatives of the Bathybatini tribe in the only monogenean parasite described from this habitat, Cichlidogyrus casuarinus Pariselle, Muterezi Bukinga & Vanhove, 2015 suggest a link between lower specificity and lower host density. Conversely, high host specificity and species richness are reported for monogeneans of the lake’s littoral cichlids. We further investigated whether the deep-water environment in Lake Tanganyika is really monogenean species-depauperate by investigating the monogenean fauna of Trematocara unimaculatum (a representative of the tribe Trematocarini, the sister lineage of the Bathybatini) and Benthochromis horii, a member of the tribe Benthochromini, found in the same deep-water habitat as the already known hosts of C. casuarinus.

Methods

Sclerotised structures of the collected monogenean individuals were characterised morphologically using light microscopy and morphometrics.

Results

Both examined cichlid species are infected by a single monogenean species each, which are new to science. They are described as Cichlidogyrus brunnensis n. sp., infecting T. unimaculatum, and Cichlidogyrus attenboroughi n. sp., parasitising on B. horii. Diagnostic characteristics include the distal bifurcation of the accessory piece in C. brunnensis n. sp. and the combination of long auricles and no heel in C. attenboroughi n. sp. In addition C. brunnensis n. sp. does not resemble C. casuarinus, the only species of Cichlidogyrus thus far reported from the Bathybatini. Also Cichlidogyrus attenboroughi n. sp. does not resemble any of the monogenean species documented from the pelagic zone of the lake and is among the few described species of Cichlidogyrus without heel.

Conclusions

As two new and non-resembling Cichlidogyrus species are described from T. unimaculatum and B. horii, colonisation of the deep-water habitat by more than one morphotype of Cichlidogyrus is evident. Based on morphological comparisons with previously described monogenean species, parasite transfers with the littoral zone are possible. Therefore, parasites of pelagic cichlids in the lake do not seem to only mirror host phylogeny and the evolutionary history of this host-parasite system merits further attention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Considering the high number of vertebrate [1–4] and invertebrate [5–11] radiations described from Lake Tanganyika, it is surprising that its parasite fauna has been mostly overlooked for many years. Parasitological research in Lake Tanganyika has increased since about five years, improving our understanding of mainly its monogenean fauna [12–17]. The Monogenea van Beneden, 1858 is a group of mostly ectoparasitic flatworms described mainly from freshwater fishes and phylogenetically closely related to Cestoda van Beneden, 1849 [18, 19]. Due to their direct life-cycles and high degree of structural adaptations influenced by host preferences, they are considered as useful targets for investigations focusing on evolutionary processes in parasites [20–23] as well as for research on the taxonomy [16], biogeography [24–26] or phylogeny of their host species [27]. This is nicely exemplified when focusing on the cichlid fishes (family Cichlidae), one of the most diverse host fish families with a remarkable evolutionary history featuring rapid radiation processes [1, 28, 29]. Cichlids display huge species richness and are usually classified into tribes [30].

Lake Tanganyika in the African Rift Valley is the second deepest lake in the world and figures as a natural experiment displaying the greatest diversity of speciation mechanisms in cichlids compared to the other major African lakes [28, 31]. Lake Tanganyika is inhabited by more than 200 cichlid species [31], classified into 15 different tribes [32–34]. Six monogenean genera have been reported to infect African cichlid fishes. Cichlidogyrus Paperna, 1960 is the most species-rich one [15, 24, 35]. To date, 22 species of Cichlidogyrus have been described in Lake Tanganyika from 18 cichlid hosts representing seven different tribes [12–17]. Most records originated from the littoral zone where these parasites were shown to display quite strong host specificity [27]. Cichlid species richness in Lake Tanganyika decreases with water depth [31], with most of the diversity found in shallow littoral habitats. This situation is caused by three main factors: reduction of niche diversity in the deep-water habitat, the fact that the short-wave length blue light spectrum in the depths does not promote diversification mechanisms, and the absence of strong geographic barriers [36–39]. The same pattern of lower species richness, along with lower host specificity, was documented in monogeneans and suggested to be a consequence of lower host availability. For example, the generalist C. casuarinus Pariselle, Muterezi Bukinga & Vanhove, 2015 has been reported from six bathybatine cichlid species belonging to the genera Bathybates and Hemibates [13, Kmentová et al., unpublished observation]. To further our knowledge of the monogenean diversity in deep-water Tanganyika cichlids, we examined Trematocara unimaculatum Boulenger, 1901, a representative of the tribe Trematocarini, the sister group of the Bathybatini [34, 40], and Benthochromis horii Takahashi, 2008, a cichlid species belonging to another deep-water tribe, Benthochromini, which is only distantly related to the Bathybatini [31, 34], but found in the same habitat as the previously reported hosts of C. casuarinus.

Methods

Fishes were bought on fish markets in the capital city of Burundi, Bujumbura (3°23'S, 29°22'E) in September 2013 and identified in situ. Eight specimens of Trematocara unimaculatum and ten of Benthochromis horii were dissected according to the standard protocol of Ergens & Lom [41]. Gills were preserved in ethanol until subsequent inspection for monogeneans under an Olympus SYX7 stereomicroscope. Parasites were mounted on slides under coverslips using Hoyer’s medium, enabling visualisation of sclerotised structures [42]. Measurements of sclerotised structures were taken at a magnification of 1000× (objective × 100 immersion, ocular × 10) using an Olympus BX51 microscope with incorporated phase contrast and the software MicroImage version 4.0. In total, 26 different metrical features were measured and are presented in micrometres. The terminology follows [17, 43] while “straight length” and “straight width” mean the linear length of the measured structure. Drawings were made using an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with a drawing tube and OLYMPUS KL 1500 LED illumination and edited with a graphics tablet compatible with Adobe Illustrator 16.0.0 and Adobe Photoshop 13.0. The type-material was deposited in the invertebrate collection of the Royal Museum for Central Africa (RMCA), Tervuren, Belgium; the Iziko South African Museum (SAMC), Cape Town, Republic of South Africa; the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle (MNHN), Paris, France; and the Natural History Museum (NHMUK), London, United Kingdom. Tissue samples of the hosts are available in the ichthyology collection of the RMCA.

Results

Trematocara unimaculatum and B. horii were each infected by a single different monogenean species belonging to Cichlidogyrus. Following Paperna [44] and Pariselle et al. [45], the genus is characterised by a haptor consisting of two pairs of medium-sized anchors, seven pairs of marginal hooks, two transversal bars (the dorsal one with two auricles; the ventral one curved and articulated), a male copulatory organ (MCO) with copulatory tube and most often a heel and (see [15]) an accessory piece; and a vagina which is not always sclerotised. Both collected Cichlidogyrus spp. are new to science and their descriptions are presented below. Since the species description in dactylogyrid monogenean taxonomy is more than anything else based on the morphology of their sclerotised structures [19, 46], the depiction of soft parts and internal organs is omitted and a differential diagnosis focused on details of the parasites’ hard parts is provided.

Family Dactylogyridae Yamaguti, 1963

Genus Cichlidogyrus Paperna, 1960

Cichlidogyrus brunnensis n. sp.

Type-host: Trematocara unimaculatum Boulenger, 1901 (Cichlidae).

Type-locality : Bujumbura, Lake Tanganyika, Burundi (3°23'S, 29°22'E), coll. 4.ix.2013.

Type-material: Holotype: MRAC MT.37812. Paratypes: MRAC MT.37812-4 (16 specimens); MNHN HEL549-550 (4 specimens); NHMUK 2015.12.10.1-2 (3 specimens); SAMC-A082649-50 (3 specimens).

Site in host: Gills.

Infection parameters: Five of eight fish infected with 2–23 specimens.

ZooBank registration: To comply with the regulations set out in article 8.5 of the amended 2012 version of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) [47], details of the new species have been submitted to ZooBank. The Life Science Identifier (LSID) of the article is urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:F7E8CC4E-8B91-48A9-9131-3BBBC80F798F. The LSID for the new name Cichlidogyrus brunnensis is urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:270003FD-6002-404B-BD38-37F5ED161EEA.

Etymology: The species epithet was chosen after the biggest Moravian city, Brno, Czech Republic, where Masaryk University was founded, in gratitude for the education and support provided.

Description

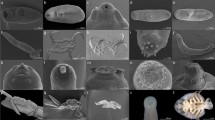

[Based on 30 specimens; Figs. 1, 3a, c; see measurements in Table 1.] Dorsal anchor with poorly incised roots and well-developed, regularly curved short point. Ventral anchors larger than dorsal anchors, with longer distance between base and point of hook, poorly incised roots, short point. Dorsal bar large, wide, straight, with relatively short, wide auricles. Ventral bar thick, short, branches straight with constant width. Hooks 7 pairs, pairs 1–4, 6 and 7 relatively short (sensu [35]) compared to pair 5, considering ontogenetic development as pair 5 retains its larval size); pair 7 largest. MCO small, with narrow, thin-walled tubular copulatory tube; accessory piece of same length as copulatory tube with distal bifurcation starting in distal quarter, and short heel. Sclerotised vagina not observed.

Differential diagnosis

The anchors of this species resemble those of its non-Tanganyika congeners Cichlidogyrus sclerosus Paperna & Thurston, 1969 [48], C. amphoratus Pariselle & Euzet, 1996 [49] and C. giostrai Pariselle, Bilong Bilong & Euzet, 2003 [45] described from Oreochromis mossambicus (Peters, 1852), Tilapia louka Thys van den Audenaerde, 1969 and Sarotherodon caudomarginatus (Boulenger, 1916), respectively, in their broad base and almost non-incised roots of the anchors. However, the exceptional shape of its accessory piece, with a forked ending, as well as the large ventral anchor in comparison to the dorsal one, make C. brunnensis n. sp. clearly distinguishable among all species of Cichlidogyrus described so far. Moreover, the shape of the anchors, specifically their poorly incised roots and the proportionally large hook, is unique among all other known congeners in Lake Tanganyika: Cichlidogyrus vandekerkhovei Vanhove, Volckaert & Pariselle, 2011; C. makasai Vanhove, Volckaert & Pariselle, 2011; C. sturmbaueri Vanhove, Volckaert & Pariselle, 2011; C. centesimus Vanhove, Volckaert & Pariselle, 2011; C. gillardinae Muterezi Bukinga, Vanhove, Van Steenberge & Pariselle, 2012; C. mbirizei Muterezi Bukinga, Vanhove, Van Steenberge & Pariselle, 2012; C. nshomboi Muterezi Bukinga, Vanhove, Van Steenberge & Pariselle, 2012; C. mulimbwai Muterezi Bukinga, Vanhove, Van Steenberge & Pariselle, 2012; C. muzumanii Muterezi Bukinga, Vanhove, Van Steenberge & Pariselle, 2012; C. steenbergei Gillardin, Vanhove, Pariselle, Huyse & Volckaert, 2012; C. gistelincki Gillardin, Vanhove, Pariselle, Huyse & Volckaert, 2012; C. irenae Gillardin, Vanhove, Pariselle, Huyse & Volckaert, 2012; C. buescheri Pariselle & Vanhove, 2015; C. schreyenbrichardorum Pariselle & Vanhove, 2015; C. vealli Pariselle & Vanhove, 2015; C. banyankimbonai Pariselle & Vanhove, 2015; C. muterezii Pariselle & Vanhove, 2015; C. raeymaekersi Pariselle & Vanhove, 2015; C. georgesmertensi Pariselle & Vanhove, 2015; C. franswittei Pariselle & Vanhove, 2015; C. frankwillemsi Pariselle & Vanhove, 2015 and C. casuarinus. The latter species infects bathybatine cichlids, the sister group of the Trematocarini, which among others also comprises T. unimaculatum, the type-host of C. brunnensis n. sp., but C. casuarinus is morphologically very different; it is easily distinguished by the spirally-coiled thickening in the wall of the copulatory tube. Although the forked shape of the accessory piece of C. brunnensis n. sp. is similar to an undescribed species collected from Limnochromis auritus [50], a member of Lake Tanganyika’s benthic deep water cichlid tribe Limnochomini, differences in haptoral sclerotised structures, namely the length of the dorsal bar auricles (on average 11.1 μm in C. brunnensis vs c.45 μm in the undescribed species) and the shape of the anchors allows clear distinction between them.

Cichlidogyrus attenboroughi n. sp.

Type-host: Benthochromis horii Takahashi, 2008 (Cichlidae).

Type-locality: Bujumbura, Lake Tanganyika, Burundi (3°23'S, 29°22'E).

Type-material: Holotype: MRAC MT.37815. Paratypes: MRAC: MT.37815-7 (10 specimens); MNHN HEL551-552 (5 specimens); NHMUK 2015.12.10. 3–4 (5 specimens); SAMC-A082651-2 (4 specimens).

Site in host: Gills.

Infection parameters: Three of ten fish infected with 4–27 specimens.

ZooBank registration: To comply with the regulations set out in article 8.5 of the amended 2012 version of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) [47], details of the new species have been submitted to ZooBank. The Life Science Identifier (LSID) of the article is urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:F7E8CC4E-8B91-48A9-9131-3BBBC80F798F. The LSID for the new name Cichlidogyrus attenboroughi is urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:AC051EA5-FCAC-49A8-9048-02E44E80654D.

Etymology: The species epithet honours the English scientist and broadcaster Sir David Frederick Attenborough, in gratitude for the insights and inspiration he gave to so many people to study and protect nature and biodiversity.

Description

[Based on 30 specimens; Figs. 2, 3b, d; see measurements in Table 1.] Dorsal anchors with different root size and regularly curved points. Ventral anchors larger in total size and more similar root size than dorsal anchors. Dorsal bar thin, with relatively long narrow auricles. Ventral bar thin, long, with constant width. Hooks 7 pairs, pair 4 relatively long; pairs 1 and 5 of equal length. MCO with slender copulatory tube with relatively thick wall; accessory piece broader than copulatory tube. No heel or sclerotised vagina observed.

Haptoral and male genital sclerotised structures of Cichlidogyrus species described in this study (Hoyer’s medium, phase-contrast photomicrographs). a Opisthaptor of C. brunnensis n. sp. b Opisthaptor of C. attenboroughi n. sp. c Male copulatory organ of C. brunnensis n. sp. d Male copulatory organ of C. attenboroughi n. sp

Differential diagnosis

There are congeners in Lake Tanganyika that share with C. attenboroughi n. sp. the small size of the first pair of hooks and the presence of long dorsal bar auricles, namely C. makasai and C. vandekerkhovei recorded from Ophthalmotilapia ventralis (Boulenger, 1898),O. nasuta (Poll & Matthes, 1962) and O. boops (Boulenger, 1901). Cichlidogyrus attenboroughi n. sp. differs from these species by the shorter length of the auricles (18.4 μm in C. attenboroughi vs 20 μm in C. makasai and 30 μm in C. vandekerkhovei) and in possessing a MCO with a simple accessory piece and without a heel. Because of the shape of the ventral anchor and the equal size among the first and the second pairs of hooks this species could be mistaken with C. gistelincki infecting Ctenochromis horei (Günther, 1894), C. irenae described from Gnathochromis pfefferi (Boulenger, 1898) and C. steenbergei parasitising Limnotilapia dardennii (Boulenger, 1899) all of which are also present in Lake Tanganyika. However, in contrast to these species, there is no developed heel in the MCO of C. attenboroughi n. sp. Three other species have been described lacking a heel: C. haplochromii Paperna & Thurston, [48] described from Pharyngochromis darlingi (Boulenger, 1911); C. tilapiae Paperna, 1960 recorded from, among others, Oreochromis leucostictus (Trewavas, 1933) and Sarotherodon galilaeus (Linnaeus, 1758) and C. arfii Pariselle & Euzet, 1995 described from Pelmatochromis buettikoferi (Steindachner, 1894). However, the haptoral region of the latter species cannot be confused with C. attenboroughi n. sp. because of the different edge of the dorsal anchor roots, the relative length of the first pairs of hooks (the smallest pair in C. attenboroughi n. sp. and the biggest pair in C. arfii) or the length of the auricles (18.4 μm in C. attenboroughi n. sp. vs 9 μm in C. arfii) [51]. The most evident difference between C. attenboroughi n. sp. and C. tilapiae is the size of the dorsal anchor as well as the maximal straight width of the dorsal bar and the length of its auricles [45]. Differences with C. haplochromii are visible in the dorsal bar, which has shorter and less slender auricles in comparison to C. attenboroughi n. sp. [48].

Discussion

The presence of a single monogenean species, phenotypically substantially different from C. casuarinus, on T. unimaculatum, indicates that closely related deep-water cichlid lineages have been colonised by several Cichlidogyrus lineages. Moreover, comparison with other species reported from Lake Tanganyika so far points to multiple origins of the deep-water representatives of Cichlidogyrus. Indeed, this is suggested by the phenotypic similarity of C. brunnensis n. sp. to an undescribed species collected from the benthic cichlid Limnochromis auritus (Boulenger, 1901) [50] and its quite different morphology of sclerotised structures as compared to C. attenboroughi n. sp., which infects another deep-water cichlid species, Benthochromis horii. Furthermore, C. attenboroughi n. sp. shares morphological characteristics of its haptoral region with two species of Cichlidogyrus (C. vandekerkhovei and C. makasai) recorded from three species of Ophthalmotilapia as well as with species described from tropheine cichlids [14, 15]. Interestingly, C. casuarinus infecting Bathybatini and C. nshomboi infecting Boulengerochromis microlepis (Boulenger, 1899), a cichlid species phylogenetically closely related to the Trematocarini and Bathybatini [52–54], are similar to C. centesimus. The latter infects three species of the genus Ophthalmotilapia, which belongs to the tribe Ectodini. Cichlidogyrus casuarinus, C. nshomboi and C. centesimus share the unique spirally coiled thickening of the wall of the copulatory tube [12, 13, 15]. Both ectodine and tropheine cichlids occur in shallow water and are only distantly related to Bathybatini, Trematocarini, Benthochromini and Boulengerochromis. Therefore, other scenarios such as host habitat preferences influencing the chance of transmission [55] or shared morphological characters of the host affecting monogenean phenotypes might have played a role in the evolutionary history of this monogenean assemblage [56, 57].

Conclusions

The inventory of monogeneans from Lake Tanganyika has been supplemented by the description of C. brunnensis n. sp. and C. attenboroughi n. sp. collected from T. unimaculatum and B. horii, respectively. These are the first monogeneans reported from the respective cichlid species and tribes. The known host range of C. casuarinus still remains limited to the genera Bathybates and Hemibates, although further investigations are needed to confirm this observation. Our result is consistent with taxonomic hypotheses that include the Trematocarini as a separate tribe [34, 58], which, together with the Bathybatini, constitute the sister group of the Boulengerochromini [53]. Cichlidogyrus casuarinus, parasitising bathybatine cichlids, morphologically resembles C. nshomboi (collected from B. microlepis, see [12, 13]) more than C. brunnensis n. sp. which infects T. unimaculatum, a representative of the Bathybatini’s sister group Trematocarini. Hence, probably other speciation mechanisms rather than co-speciation have occurred in the evolutionary history of this deep-water parasite-host system. An exhaustive list of Cichlidogyrus species occurring on deep-water cichlid species in Lake Tanganyika, together with genetic analyses and a co-phylogenetic approach, are needed to verify these alternative scenarios. The reported lower monogenean host specificity is probably correlated with small diversity and population densities of hosts [58–60] influenced by lower temperature and reduction of light as communication of cichlids is mainly based on visual signals [61]. Decline of parasite diversity is probably also related to the distance from the shore as well as to specific host behavioural characteristics [60]. Although the deep-water monogenean fauna in Lake Tanganyika seems to be less species-rich than the littoral one [27] it is premature to exactly quantify differences in monogenean species richness per host, or to conclude whether the deep-water monogenean fauna is indeed depauperate.

Abbreviations

MCO, male copulatory organ

References

Sturmbauer C. Explosive speciation in cichlid of the African Great Lakes: a dynamic model of adaptive radiation. J Fish Biol. 1998;53:18–36.

Day JJ, Peart CR, Brown KJ, Friel JP, Bills R, Moritz T. Continental diversification of an African catfish radiation (Mochokidae: Synodontis). Syst Biol. 2013;62:351–65.

Brown KJ, Rüber L, Bills R, Day JJ. Mastacembelid eels support Lake Tanganyika as an evolutionary hotspot of diversification. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10:188.

Peart CR, Bills R, Wilkinson M, Day JJ. Nocturnal claroteine catfishes reveal dual colonisation but a single radiation in Lake Tanganyika. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2014;73:119–28.

Michel E. Evolutionary diversification of rift lake gastropods: Morphology, anatomy, genetics and biogeography of Lavigeria (Mollusca: Thiaridae) in Lake Tanganyika. Tucson: The University of Arizona; 1995.

Glaubrecht M. Adaptive radiation of thalassoid gastropods in Lake Tanganyika, East Africa: morphology and systematization of a paludomid species flock in an ancient lake. Zoosystematics Evol. 2008;84:71–122.

Fryer G. Comparative aspects of adaptive radiation and speciation in Lake Baikal and the great rift lakes of Africa. Hydrobiologia. 1991;211:137–46.

Schön I, Martens K. Molecular analyses of ostracod flocks from Lake Baikal and Lake Tanganyika. Hydrobiologia. 2011;682:91–110.

Marijnissen SAE, Michel E, Daniels SR, Erpenbeck D, Menken SBJ, Schram FR. Molecular evidence for recent divergence of Lake Tanganyika endemic crabs (Decapoda: Platythelphusidae). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006;40:628–34.

Erpenbeck D, Weier T, de Voogd NJ, Wörheide G, Sutcliffe P, Todd JA, Michel E. Insights into the evolution of freshwater sponges (Porifera: Demospongiae: Spongillina): Barcoding and phylogenetic data from Lake Tanganyika endemics indicate multiple invasions and unsettle existing taxonomy. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2011;61:231–6.

Meixner MJ, Lüter C, Eckert C, Itskovich V, Janussen D, von Rintelen T, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of freshwater sponges provide evidence for endemism and radiation in ancient lakes. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2007;45:875–86.

Muterezi Bukinga F, Vanhove MPM, Van Steenberge M, Pariselle A. Ancyrocephalidae (Monogenea) of Lake Tanganyika: III: Cichlidogyrus infecting the world’s biggest cichlid and the non-endemic tribes Haplochromini, Oreochromini and Tylochromini (Teleostei, Cichlidae). Parasitol Res. 2012;111:2049–61.

Pariselle A, Muterezi Bukinga F, Van Steenberge M, Vanhove MPM. Ancyrocephalidae (Monogenea) of Lake Tanganyika: IV: Cichlidogyrus parasitizing species of Bathybatini (Teleostei, Cichlidae): reduced host-specificity in the deepwater realm? Hydrobiologia. 2015;748:99–119.

Gillardin C, Vanhove MPM, Pariselle A, Huyse T, Volckaert FAM. Ancyrocephalidae (Monogenea) of Lake Tanganyika: II: description of the first Cichlidogyrus spp. parasites from Tropheini fish hosts (Teleostei, Cichlidae). Parasitol Res. 2012;110:305–13.

Vanhove MPM, Volckaert FAM, Pariselle A. Ancyrocephalidae (Monogenea) of Lake Tanganyika: I: Four new species of Cichlidogyrus from Ophthalmotilapia ventralis (Teleostei: Cichlidae), the first record of this parasite family in the basin. Zoologia. 2011;28:253–63.

Van Steenberge M, Pariselle A, Huyse T, Volckaert FAM, Snoeks J, Vanhove MPM. Morphology, molecules, and monogenean parasites: an example of an integrative approach to cichlid biodiversity. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124474.

Pariselle A, Van Steenberge M, Snoeks J, Volckaert FAM, Huyse T, Vanhove MPM. Ancyrocephalidae (Monogenea) of Lake Tanganyika: Does the Cichlidogyrus parasite fauna of Interochromis loocki (Teleostei, Cichlidae) reflect its host’s phylogenetic affinities? Contrib Zool. 2015;84:25–38.

Boeger WA, Kritsky DC. Coevolution of the Monogenoidea (Platyhelminthes) based on a revised hypothesis of parasite phylogeny. Int J Parasitol. 1997;27:1495–511.

Pugachev ON, Gerasev PI, Gussev AV, Ergens R, Khotenowsky I. Guide to Monogenoidea of freshwater fish of Palaeartic and Amur Regions. Milan: Ledizione-LediPublishing; 2009.

Šimková A, Ondráčková M, Gelnar M, Morand S. Morphology and coexistence of congeneric ectoparasite species: reinforcement of reproductive isolation? Biol J Linn Soc. 2002;76:125–35.

Šimková A, Morand S, Jobet E, Gelnar M, Verneau O. Molecular phylogeny of congeneric monogenean parasites (Dactylogyrus): a case of intrahost speciation. Evolution. 2004;58:1001–18.

Mendlová M, Desdevises Y, Civáňová K, Pariselle A, Šimková A. Monogeneans of west African cichlid fish: Evolution and cophylogenetic interactions. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37268.

Vanhove MPM, Huyse T. Host-specificity and species-jumps in fish-parasite systems. In: Morand S, Krasnov B, Littlewood DTJ, editors. Parasite diversity and diversification: evolutionary ecology meets phylogenetics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2015. p. 401–19.

Pariselle A, Boeger WA, Snoeks J, Bilong Bilong CF, Morand S, Vanhove MPM. The monogenean parasite fauna of cichlids: a potential tool for host biogeography. Int J Evol Biol. 2011;2011:ID 471480.

Vanhove MPM, Van Steenberge M, Dessein S, Volckaert FAM, Snoeks J, Huyse T, Pariselle A. Biogeographical implications of Zambezian Cichlidogyrus species (Platyhelminthes: Monogenea: Ancyrocephalidae) parasitizing Congolian cichlids. Zootaxa. 2013;3608:398–400.

Barson M, Přikrylová I, Vanhove MPM, Huyse T. Parasite hybridization in African Macrogyrodactylus spp. (Monogenea, Platyhelminthes) signals historical host distribution. Parasitology. 2010;137:1585–95.

Vanhove MPM, Pariselle A, Van Steenberge M, Raeymaekers JAM, Hablützel PI, Gillardin C, et al. Hidden biodiversity in an ancient lake: phylogenetic congruence between Lake Tanganyika tropheine cichlids and their monogenean flatworm parasites. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13669.

Sturmbauer C, Husemann M, Danley P. Explosive speciation and adaptive radiation of East African cichlid fishes. In: Frank EH, Habel JC, editors. Biodiversity hotspots. Distribution and protection of conservation priority areas. London: Springer; 2011. p. 333–62.

Santos ME, Salzburger W. Evolution. How cichlids diversify. Science. 2012;338:619–21.

Poll M. Classification des cichlidae du lac Tanganika. Académie R Belgique Membres la Cl des Sci. 1986;45:1–163.

Koblmüller S, Sefc KM, Sturmbauer C. The Lake Tanganyika cichlid species assemblage: Recent advances in molecular phylogenetics. Hydrobiologia. 2008;615:5–20.

Takahashi T. Greenwoodochromini Takahashi from Lake Tanganyika is a junior synonym of Limnochromini Poll (Perciformes: Cichlidae). J Fish Biol. 2014;84:929–36.

Takahashi T. Systematics of Tanganyikan cichlid fishes (Teleostei: Perciformes). Ichthyol Res. 2003;50:367–82.

Takahashi T, Sota T. A robust phylogeny among major lineages of the East African cichlids. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2016;100:234–42.

Pariselle A, Euzet L. Systematic revision of dactylogyridean parasites (Monogenea) from cichlid fishes in Africa, the Levant and Madagascar. Zoosystema. 2009;31:849–98.

Seehausen O. Cichlid fish diversity threatened by eutrophication that curbs sexual selection. Science. 1997;277:1808–11.

Seehausen O, Van Alphen JJM, Lande R. Color polymorphism and sex ratio distortion in a cichlid fish as an incipient stage in sympatric speciation by sexual selection. Ecol Lett. 1999;2:367–78.

Knight ME, Turner GF. Laboratory mating trials indicate incipient speciation by sexual selection among populations of the cichlid fish Pseudotropheus zebra from Lake Malawi. Proc R Soc B. 2004;271:675–80.

Maan ME, Seehausen O, Söderberg L, Johnson L, Ripmeester EAP, Mrosso HDJ, et al. Intraspecific sexual selection on a speciation trait, male coloration, in the Lake Victoria cichlid Pundamilia nyererei. Proc R Soc B. 2004;271:2445–52.

Kirchberger PC, Sefc KM, Sturmbauer C, Koblmüller S. Evolutionary history of Lake Tanganyika's predatory deepwater cichlids. Int J Evol Biol. 2012;2012:716209.

Ergens R, Lom J. Causative Agents of Fish Diseases. Prague: Academia; 1970.

Humason GL. Animal tissue techniques. 4th ed. San Francisco: Freeman and Company; 1979.

Řehulková E, Mendlová M, Šimková A. Two new species of Cichlidogyrus (Monogenea: Dactylogyridae) parasitizing the gills of African cichlid fishes (Perciformes) from Senegal: Morphometric and molecular characterization. Parasitol Res. 2013;112:1399–410.

Paperna I. Studies on monogenetic trematodes in Israel, 2: Monogenetic trematodes of cichlids. Bamidgeh. 1960;12:20–33.

Pariselle A, Bilong Bilong CF, Euzet L. Four new species of Cichlidogyrus Paperna, 1960 (Monogenea, Ancyrocephalidae), all gill parasites from African mouthbreeder tilapias of the genera Sarotherodon and Oreochromis (Pisces, Cichlidae), with a redescription of C. thurstonae Ergens, 1981. Syst Parasitol. 2003;56:201–10.

Vignon M, Pariselle A, Vanhove MPM. Modularity in attachment organs of African Cichlidogyrus (Platyhelminthes: Monogenea: Ancyrocephalidae) reflects phylogeny rather than host specificity or geographic distribution. Biol J Linn Soc. 2011;102:694–706.

International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. Amendment of articles 8, 9, 10, 21 and 78 of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature to expand and refine methods of publication. Zootaxa. 2012;3450:1–7.

Paperna I, Thurston JP. Monogenetic trematodes collected from cichlid fish in Uganda;including the description of five new species of Cichlidogyrus. Rev Zool Bot Afr. 1969;79:15–33.

Pariselle A, Euzet L. Cichlidogyrus Paperna, 1960 (Monogenea, Ancyrocephalidae): gill parasites from West African Cichlidae of the subgenus Coptodon Regan, 1920 (Pisces), with descriptions of six new species. Syst Parasitol. 1996;34:109–24.

Kmentová N, Gelnar M, Koblmüller S, Vanhove MPM. First insights into the diversity of gill monogeneans of’Gnathochromis' and Limnochromis (Teleostei, Cichlidae) in Burundi: do the parasites mirror host ecology and phylogenetic history? PeerJ. 2016;4:e1629.

Pariselle A, Euzet L. Trois Monogènes nouveaux parasites branchiaux de Pelmatochromis buettikoferi (Steindachner, 1895)(Cichlidae) en Guinée. Parasite. 1995;2:203–9.

Meyer BS, Matschiner M, Salzburger W. A tribal level phylogeny of Lake Tanganyika cichlid fishes based on a genomic multi-marker approach. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2015;83:56–71.

Muschick M, Indermaur A, Salzburger W. Convergent evolution within an adaptive radiation of cichlid fishes. Curr Biol. 2012;22:2362–8.

Weiss JD, Cotterill FPD, Schliewen UK. Lake Tanganyika - A “melting pot” of ancient and young cichlid lineages (Teleostei: Cichlidae)? PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125043.

Desdevises Y, Morand S, Legendre P. Evolution and determinants of host specificity in the genus Lamellodiscus (Monogenea). Biol J Linn Soc. 2002;77:431–43.

Vignon M, Sasal P. The use of geometric morphometrics in understanding shape variability of sclerotized haptoral structures of monogeneans (Platyhelminthes) with insights into biogeographic variability. Parasitol Int. 2010;59:183–91.

Morand S, Šimková A, Matějusová I, Plaisance L, Verneau O, Desdevises Y. Investigating patterns may reveal processes: evolutionary ecology of ectoparasitic monogeneans. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:111–9.

Schoelinck C, Cruaud C, Justine JL. Are all species of Pseudorhabdosynochus strictly host specific? - A molecular study. Parasitol Int. 2012;61:356–9.

Justine J-L, Beveridge I, Boxshall G, Bray RA, Miller TL, Moravec F, et al. An annotated list of fish parasites (Isopoda, Copepoda, Monogenea, Digenea, Cestoda, Nematoda) collected from Snappers and Bream (Lutjanidae, Nemipteridae, Caesionidae) in New Caledonia confirms high parasite biodiversity on coral reef fish. Aquat Biosyst. 2012;8:22.

Campbell RA, Headrich RL, Munroe TA. Parasitism and ecological relationships among deep-see benthic fishes. Mar Biol. 1980;57:301–13.

Barlow G. The Cichlid Fishes. Nature’s Grand Experiment In Evolution. Cambridge: Perseus Publishing; 2000.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the help of the people involved in the field work and sampling procedure (Andrea Šimková, Eva Řehulková, Šárka Mašová, Iva Přikrylová, Radim Blažek, Veronika Nezhybová, Gaspard Banyankimbona and the Schreyen-Brichard family and the technical staff of Fishes of Burundi). Tine Huyse and Maarten Van Steenberge are thanked for their valuable comments, Tetsumi Takahashi for confirming our Benthochromis species identification and the parasitological lab of Masaryk University in Brno for its hospitality.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Czech Science Foundation (GBP505/12/G112-ECIP).

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article. The type-material of the new species described in this study is deposited in the invertebrate collection of the Royal Museum for Central Africa (RMCA), Tervuren, Belgium; the Iziko South African Museum (SAMC), Cape Town, Republic of South Africa; the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle (MNHN), Paris, France; and the Natural History Museum (NHMUK), London, United Kingdom (see "Type-material" for accession numbers). Tissue samples of the hosts are available in the ichthyology collection of the RMCA.

Authors’ contributions

MPMV designed and supervised this study. MG provided scientific background in the field of monogenean research. SK identified fish species, contributed to sampling and provided scientific background on Lake Tanganyika and its ichthyofauna. NK performed the morphological characterisation and described the species. MPMV and NK analysed the data and wrote the paper. SK revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Masaryk University. The approval number which allows us to work with vertebrate animals is CZ01308.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kmentová, N., Gelnar, M., Koblmüller, S. et al. Deep-water parasite diversity in Lake Tanganyika: description of two new monogenean species from benthopelagic cichlid fishes. Parasites Vectors 9, 426 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1696-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1696-x