Abstract

Introduction

Metformin use has recently been observed to decrease both the rate and mortality of breast cancer. Our study was aim to determine whether metformin use is associated with survival in diabetic breast cancer patients by breast cancer subtype and systemic treatment.

Methods

Data from the Asan Medical Center Breast Cancer Database from 1997 to 2007 were analyzed. The study cohort comprised 6,967 nondiabetic patients, 202 diabetic patients treated with metformin, and 184 diabetic patients that did not receive metformin. Patients who were divided into three groups by diabetes status and metformin use were also divided into four subgroups by hormone receptor and HER2-neu status.

Results

In Kaplan-Meier analysis, the metformin group had a significantly better overall and cancer specific survival outcome compared with non metformin diabetic group (P <0.005 for both). There was no difference in survival between the nondiabetic and metformin groups. In multivariate analysis, Compared with metformin group, patients who did not receive metformin tended to have a higher risk of metastasis with HR 5.37 (95 % CI, 1.88 to 15.28) and breast cancer death with HR 6.51 (95 % CI, 1.88 to 15.28) on the hormone receptor-positive and HER2-negative breast cancer. The significant survival benefit of metformin observed in diabetic patients who received chemotherapy and endocrine therapy (HR for disease free survival 2.14; 95 % CI 1.14 to 4.04) was not seen in diabetic patients who did not receive these treatments.

Conclusion

Patients receiving metformin treatment when breast cancer diagnosis show a better prognosis only if they have hormone receptor-positive, HER2-positive tumors. Metformin treatment might provide a survival benefit when added to systemic therapy in diabetic patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes has been found to be a risk factor for breast cancer in some studies, and patients with diabetes may have poorer outcomes than nondiabetic patients [1– 3]. A recent British cohort study found that women with breast cancer and pre-existing diabetes had a 49 % (95 % CI, 1.17 to 1.88) increased all-cause mortality risk compared with women with breast cancer but without diabetes [4]. Obesity is associated with type 2 diabetes and is itself a risk factor for breast cancer and possibly for a poorer outcome from this cancer [5]. The common factor linking diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome to cancer may be insulin resistance and the consequent hyperinsulinemia associated with these conditions [6].

Metformin is widely used in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus to increase insulin sensitivity and improve glycemic control [7, 8]. In addition, numerous experimental, epidemiologic, observational, and clinical studies have shown that metformin has antitumor effects [9, 10]. In particular, metformin treatment has been associated with lower breast cancer incidence among patients with diabetes and higher pathologic complete response in patients with early-stage breast cancer who were receiving neoadjuvant therapy [11]. Metformin could decrease breast cancer cell growth either indirectly by reducing circulating insulin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF) or directly via activation of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) [12]. Initiation of an AMPK-dependent energy stress response, resulting in inhibition of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway, leads to reduced protein synthesis and proliferation of cancer cells [13]. Thus, the anticancer effects of metformin are mediated through a systemic improvement in the metabolic profile and by directly targeting tumor cells [10]. However, results from observation studies on survival benefit in breast cancer patients with diabetes are conflicting. A recent study failed to show a significant reduction in breast cancer mortality in patients treated with metformin [14] but some fairly small studies have reported a beneficial effect of metformin use on survival in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2)-positive tumors [15].

Based on the evidence reviewed above, a growing number of clinical intervention studies of metformin have been initiated [16]. A phase III trial of adjuvant metformin has been initiated in women with breast cancer (NCIC CTC MA.32) [9] and a phase II trial of a neoadjuvant setting for postmenopausal breast cancer patients (METEOR study) has also started patient enrolment [10]. However, the accrual and treatment process is still ongoing, and several years of follow up are needed to determine if there is any survival benefit. In addition, little is known about the effects of metformin on different subtypes of breast cancer. In our current study, we explored the association between metformin use and survival outcomes in diabetic and nondiabetic breast cancer patients and analyzed benefit according to breast cancer subtype using immunohistochemical staining.

Methods

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Asan medical center and conducted in accordance with the Helsinki declaration. No consent was needed for this retrospective analysis using a web-based database without personal information.

Patients

Data from the Asan Medical Center Breast Cancer Database (AMCBCD) from 1997 to 2007 were analyzed. A total of 6,967 patients who were diagnosed with breast cancer and underwent surgery were included in this study. Patients were categorized by diabetes status and metformin use. They are not preselected on these exposures. Patients with a database diagnostic code (ICD-9, 250) during their outpatient clinic visits or a hospital admission were assigned to the diabetic group. For the diabetic patients, whether or not they received metformin as an antidiabetic drug on diagnosis of breast cancer was the criterion for dividing the groups into metformin or non-metformin users.

AMCBCD provides detailed clinicopathologic information on breast cancer. Eight surgical oncologists who specialized in breast cancer reviewed all available survival data for this study. Patient age (<50 years versus ≥50 years), body mass index (BMI), tumor size, lymph node involvement, hormone receptor and HER2-neu status, and adjuvant treatment status were recorded. Survival data, which included disease-free survival (DFS), cancer-specific survival (CSS) and overall survival (OS) were included in this cohort, and for the survival data, eight breast cancer specialists checked the survival data using patients’ records. Positive staining for estrogen receptor (ER) or progesterone receptor (PR) was defined as a score of more than 3+ and HER2 positivity was defined as a score of 3+ by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining or HER2 gene amplification by fluorescence in situ hybridization. The hormone receptor-positive group comprised ER-positive and/or PR-positive patients. Hormone therapy included adjuvant tamoxifen, ovarian suppression or ablation with endocrine therapy, and aromatase inhibitors. Until 2007, the anti-HER2 therapy (Trastuzumab) was not covered by Korean government health insurance. Few people had received anti-HER2 treatment among the patients who had HER2/neu-overexpressing breast cancer. The patients who had received anti-HER2 treatment were excluded from this study. Patients were divided into three groups by diabetes status and metformin use: a nondiabetic group, a metformin group (diabetic patients who received metformin), and a non-metformin group (diabetic patients who did not receive metformin after diagnosis of breast cancer). Moreover, patients were also divided into four subgroups by hormone receptor and HER2-neu status: hormone receptor-positive and HER2-negative, hormone receptor-positive and HER2-positive, hormone receptor-negative and HER2-positive, and hormone receptor-negative and HER2-negative.

Statistical analysis

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the three study groups were analyzed with the chi-square test and the differences among groups were compared with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc Scheffé test. The primary endpoint was DFS. Events used for the analysis of the end point of disease-free survival included local, regional, and contralateral breast cancer or distant breast cancer recurrence. Curves for DFS (until date of recurrence or death), CSS (until date of death from breast cancer), OS (until date of death) were calculated with the Kaplan-Meier product-limit method. Differences between groups were analyzed with the log-rank test. The relationships of risk factors (age, BMI, tumor size, lymph node metastasis, ER status, PR status, HER2-neu status, chemotherapy and hormone therapy) to disease-free survival, cancer-specific survival and OS were analyzed with multivariate Cox regression analysis. For subgroup analysis using IHC (Fig. 1, Table 1) and systemic treatment (Fig. 2), chemotherapy and hormonal therapy treatment were not considered for multivariate analysis. On multivariate analysis, the metformin group was regarded as a reference for calculating the hazard ratio (HR). To exclude a biased result, sensitivity analysis was conducted to check the consistency of the HR according to each clinically important prognostic factor for breast cancer recurrence (Fig. 3). All other statistical analyses were carried out with SPSS software (version 18.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA), with a P-value ≤0.05 considered statistically significant.

Disease-free survival according to diabetes mellitus and metformin treatment among different intrinsic subtypes using immunohistochemical staining of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2). (a) Hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative. (b) Hormone receptor-positive, HER2-positive. (c) Hormone receptor-negative, HER2- positive. (d) Hormone receptor-negative, HER2-negative Adjusted for tumor size (≤2 versus > 2 cm), lymph node status (positive versus negative), ER status, PR status, and HER2-neu status (non-amplification versus amplification). HR, hazard ratio; MET, metformin; DM, diabetes mellitus

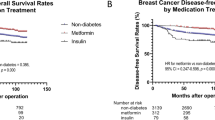

Disease-free survival according to systemic treatment of breast cancer among nondiabetic patients, diabetic patients receiving metformin, and diabetic patients not receiving metformin. (a) Patients who received chemotherapy. (b). Patients who did not receive chemotherapy. (c) Patients who received endocrine therapy. (d) Patients who did not received endocrine therapy. (e) Patients who did not receive any treatment. (f) Patients who received only chemotherapy. (g) Patients who received endocrine therapy only. (h) Patients who received chemotherapy and endocrine therapy. Adjusted for tumor size (≤2 versus > 2 cm), lymph node status (positive versus negative), estrogen receptor status, progesterone receptor status, and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2)-neu. status (non-amplification versus amplification). HR, hazard ratio; MET, metformin; DM, diabetes mellitus

Results

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics

This study cohort comprised 6,581 nondiabetic patients, 202 diabetic patients receiving metformin, and 184 diabetic patients not receiving metformin. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study patients are summarized in Table 1. Patients in the diabetic groups were older than those in the nondiabetic group (P <0.001), and the mean BMI levels were higher in the diabetic patient group (P <0.001). Patients with diabetes mellitus were also less likely to have received adjuvant chemotherapy than nondiabetic patients (P <0.001); however, there were no differences between the metformin and non-metformin groups (P = 0.155, by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Scheffé test). Tumor size, lymph node metastasis, ER and PR status, HER2-neu status, the percentages of patients receiving adjuvant hormone therapy, and the ratio of the four subgroups with ER, PR, and HER2-neu status analyzed by IHC were not significantly different among the three groups.

Breast cancer survival according to diabetes mellitus and metformin treatment

The median follow-up period was 100.3 months. In Kaplan-Meier analysis, the metformin group had significantly increased OS and cancer-specific survival compared with diabetic patients who did not receive metformin therapy (log-rank test, both P <0.005) (Fig. 4a, b). There were 1,262 recurrences (18.1 %): 42 (20.8 %) in the metformin group, 52 (28.3 %) in the non-metformin group and 1,168 (17.7 %) in the nondiabetic group. Patients in the metformin group experienced better DFS than diabetic patients in the non-metformin group, which was borderline statistically significant (log-rank test, P = 0.058; Fig. 4c) and there was no difference from the nondiabetic group. On univariate analysis, the HR for DFS in the non-metformin group compared with the metformin group was 1.50 (95 % CI 1.0 to 2.25), 1.69 (95 % CI, 1.07 to 2.68) for CSS (Table 2). After adjusting for age, BMI, tumor size, lymph node metastasis, ER, PR, and HER2-neu status, and systemic treatment, patients who did not receive treatment with metformin tended to have shorter OS (HR 1.87; 95 % CI 1.25 to 2.81), CSS (HR 1.85; 95 % CI 1.17 to 2.92) and DFS (HR 1.59; 95 % CI 1.06 to 2.39) than those of the metformin group (Fig. 4, Table 3).

Breast cancer survival according to diabetes mellitus (DM) and metformin treatment (MET). (a) Overall survival. (b) Cancer-specific survival. (c) Disease-free survival. Adjusted for tumor size (≤2 versus > 2 cm), lymph node status (positive versus negative), estrogen receptor status, progesterone receptor status, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2)-neu status (non-amplification versus amplification), chemotherapy and endocrine therapy

Subgroup analyses according to intrinsic subtype using immunohistochemical staining of ER, PR, and HER2

The Kaplan-Meier estimates of DFS stratified by the four subgroups are shown in Fig. 1. Hormone receptor-positive and HER2-positive patients showed a DFS benefit (log-rank test, P = 0.001; Fig. 1b) in those patients who received metformin compared with the diabetic non-metformin group, but the other subgroups showed no significant differences (Fig. 1a, c, d). Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis of the DFS of diabetic patients with hormone receptor-positive and HER2-positive breast cancer was carried out with a model consisting of the categorical covariates, age (<50 years versus ≥50 years), BMI (<25 kg/m2 versus ≥25 kg/m2), tumor size (T1 versus T2, 3, or 4), and node metastasis, using the metformin group as the reference. There were significant differences with regard to the risk of disease recurrence (HR 5.37; 95 % CI 1.88 to 15.28) and CSS (HR 6.51; 95 % CI 2.06 to 20.55) between the non-metformin and metformin groups, but there were no differences between the nondiabetic and metformin groups (Fig. 1b, Table 4).

Subgroup analyses according to systemic treatment of breast cancer among nondiabetic patients, diabetic patients receiving metformin, and diabetic patients not receiving metformin

For patients who did not receive chemotherapy and/or endocrine therapy, there were no statistically significant differences in DFS among the nondiabetic, non-metformin, and metformin groups. (Fig. 2a, c, e). Among the patients who had received endocrine therapy only or chemotherapy only, the metformin treatment group did not differ in DFS compared with the non-metformin treatment group (Fig. 2f, g). Among the patients who received chemotherapy and endocrine therapy, the non-metformin diabetic group had decreased DFS (HR 2.14; 95 % CI 1.14 to 4.04) compared with the metformin group, after adjusting for age, BMI, tumor size, lymph node metastasis, ER, PR and HER2.

Discussion

The results of this study confirmed that treatment with metformin after breast cancer diagnosis in diabetic patients improves DFS and reduces mortality. The most important finding was that the survival difference according to metformin treatment and diabetes was only observed on IHC staining in patients with hormone receptor-positive and HER2-positive tumors. The survival benefit was clear for patients who received chemotherapy or endocrine therapy compared with those who did not receive either of those treatments. These findings are consistent with several other recent analyses involving large numbers of subjects. To our knowledge, our present study is the first to include breast cancer clinicopathologic information and recurrence for the analysis of the relationship between metformin and breast cancer recurrence and mortality. The most common weaknesses of previous studies are a lack of information on the breast cancer characteristics, such as tumor size, lymph node metastasis, hormone receptor status, HER2 status, and treatment methods. These factors are the most important determinants of survival outcome. Hence, without considering the prognostic and predictive factors of breast cancer, any evaluation of the prognostic relationship between breast cancer and metformin is uncertain. Moreover, most previous studies have compared OS, and some have compared CSS, but few reports have explored the DFS in breast cancer and metformin treatment (Table 5) [12, 14, 15, 17–19].

Metformin is considered a hybrid anticancer compound that combines both long-lasting effects that involve the persistent lowering of blood insulin and glucose levels and the immediate potency of a cancer cell-targeting molecular agent that concurrently suppresses the pivotal AMPK/mTOR axis and several protein kinases, including crucial cancer-related tyrosine kinase receptors [20]. Metformin reduces circulating insulin levels in nondiabetic patients, which is relevant because higher insulin and C-peptide levels have been associated with poor outcomes in breast cancer patients. A window-o-opportunity study of metformin showed that it reduces Ki67 expression in breast cancer and increases apoptosis [13].

In our current study cohort, a beneficial effect of metformin was only evident in hormone receptor-positive and HER2-positive diabetic patients. Few studies have reported an effect of metformin in a specific subtype of breast cancer. Bayraktar et al. [17] reported that metformin use during adjuvant chemotherapy does not significantly impact survival outcomes in diabetic patients with triple-negative breast cancer. He et al. [15] demonstrated that metformin use was associated with significantly decreased HRs for breast cancer-specific mortality in diabetic women with HER2-positive breast cancer (HR 0.47; 95 % CI 0.24 to 0.90; P = 0.023).

The survival benefit of metformin for hormone-responsive and HER2-positive cancer can be explained via two mechanisms. First, metformin can decelerate the growth of hormone receptor-positive, HER2-positive breast cancer by suppressing the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. HER2, insulin receptor, and IGF-I receptor all act through the same downstream signaling pathway via PI3K, AKT, and mTOR. Hence, type 2 diabetes mellitus can further accelerate the growth of HER2-positive breast cancer given that AKT/mTOR signaling is already active [15]. Zhu et al. [21] have revealed the development of metformin-related implications for breast cancer prevention by showing that its systemic administration selectively targets tumor-initiating cells in a clinically relevant prevention model. Interactions between PI3K/AKT/mTOR and the estrogen and growth factor signaling and receptor tyrosine kinase cascade occur at multiple levels to promote cell proliferation and survival [22, 23]. Therefore, metformin can show an anticancer effect through suppression of one or more of these signaling pathways, which is more significant for hormone receptor-positive and HER2-positive breast cancer.

As a second mechanistic explanation for the survival benefit of metformin in patients with hormone-responsive and HER2-positive breast cancer, metformin may increase the efficacy of systemic treatments for this subtype of tumors by overcoming resistance to these therapies. ER-positive and HER2-positive tumors are considered to be an endocrine-resistant subtype of breast cancer. The resistance to antihormonal treatment is due to activation of the mTOR pathway [24, 25] and hyperactivation of IGF-I receptor [26]. Crosstalk between ER and growth factor receptor pathways has been considered to be a cause for endocrine therapy resistance in breast cancer [27]. This resistance mechanism is important in diabetic patients because the activation of the insulin receptor and IGF-I receptor signaling pathway is the main mechanism of promoting cancer cell proliferation in patients with diabetes [28, 29]. The results of the BOLEROII study, which showed mTOR inhibitor efficacy for hormone-resistant metastatic breast cancer, have indicated that hyperactivation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR is the main mechanism of secondary antihormonal treatment resistance and that the combined inhibition of ER, HER2, and mTOR is an effective treatment [30, 31]. Metformin inhibits the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway through IGF receptor inhibition.

Questions remain, however, about the clinical benefits of metformin as an anticancer agent in patients with breast cancer. We have shown from our current analyses that survival differences according to diabetes and metformin administration were significant in patients who received chemotherapy or hormone therapy. This suggests that metformin may have therapeutic efficacy by cooperatively enhancing the potency of chemotherapy or hormonal therapy. Our current results are consistent with findings of previous studies that showed that diabetic patients receiving metformin and neoadjuvant chemotherapy have a higher pathologic complete response rate than diabetic patients not receiving this drug (odds ratio 2.95; 95 % CI 1.07 to 8.17; P = 0.04) [11]. Recently, a phase III trial of adjuvant metformin has been initiated in women with breast cancer (MCIC CTG MA32) [9]. However, several years of follow-up are needed to determine the survival benefits of metformin. Moreover, a phase II clinical trial evaluating the antitumor effect of neoadjuvant metformin in postmenopausal women with ER-positive breast cancer with letrozole plus metformin or placebo is ongoing [10]. This trial will likely indicate the antitumor effects of metformin in breast cancer.

The present study had several limitations. First, the small sample size limits our ability to make firm conclusions. Second, a limitation of the present study is the lack of information on the metformin dose. Patients often receive more than one antidiabetic medication or insulin and undergo changes in their pharmacotherapy regimen over time. A recent population-based study showed no significant association between cumulative duration of past metformin use and improved survival [14]. Moreover, because the present study focuses on metformin as an antitumor drug that can reduce tumor recurrence, the past history of metformin treatment before breast cancer diagnosis was not considered. Finally, this study did not consider the severity or duration of diabetes. The use of metformin in the diabetic cohort could result in better glucose control and help maintain adequate BMI. Diabetic patients who do not take metformin have increased comorbidity compared with patients who take metformin, indicating a possible selection bias. Serial reduction of BMI could not be evaluated in the present study. But this study compared serum glucose on breast cancer surgery and the hbA1C level, which stands for the severity of diabetes for diabetic patients, but there were no significant difference between the groups.

Both the tumor-suppressing activities of metformin and the tumor-promoting effects of other diabetic conditions may also contribute to the relative survival benefit of metformin observed in our current study. Our present findings support the hypothesis that metformin improves the survival of breast cancer patients with concurrent diabetes, particularly in cases with hormone-responsive and HER2-positive tumors, receiving adjuvant systemic therapy.

Conclusion

This study is the first report to show an association between metformin and long-term breast cancer survival according to cancer subtype through the evaluation of breast cancer characteristics and metformin treatment. Moreover, our present findings can provide a background for future translational research and clinical work. We await the results of ongoing randomized trials of metformin as a treatment option for breast cancer patients.

Abbreviations

- AMCBCD:

-

Asan Medical Center Breast Cancer Database

- AMPK:

-

adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

- ANOVA:

-

analysis of variance

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CSS:

-

cancer-specific survival

- DFS:

-

disease-free survival

- ER:

-

estrogen receptor

- HER2:

-

human epidermal growth factor receptor-2

- HR:

-

hazard ratio

- IGF:

-

insulin-like growth factor

- IHC:

-

immunohistochemical

- mTOR:

-

mammalian target of rapamycin

- OS:

-

overall survival

- PR:

-

progesterone receptor

References

Chen WW, Shao YY, Shau WY, Lin ZZ, Lu YS, Chen HM, et al. The impact of diabetes mellitus on prognosis of early breast cancer in Asia. Oncologist. 2012;17:485–91.

Bowker SL, Richardson K, Marra CA, Johnson JA. Risk of breast cancer after onset of type 2 diabetes: evidence of detection bias in postmenopausal women. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2542–4.

Kaplan MA, Pekkolay Z, Kucukoner M, Inal A, Urakci Z, Ertugrul H, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and prognosis in early stage breast cancer women. Med Oncol. 2012;29:1576–80.

Redaniel MT, Jeffreys M, May MT, Ben-Shlomo Y, Martin RM. Associations of type 2 diabetes and diabetes treatment with breast cancer risk and mortality: a population-based cohort study among British women. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:1785–95.

Carmichael AR. Obesity and prognosis of breast cancer. Obes Rev. 2006;7:333–40.

Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625–38.

Goodwin PJ, Pritchard KI, Ennis M, Clemons M, Graham M, Fantus IG. Insulin-lowering effects of metformin in women with early breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2008;8:501–5.

Nathan DM, Buse JB, Davidson MB, Ferrannini E, Holman RR, Sherwin R, et al. Medical management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a consensus algorithm for the initiation and adjustment of therapy: a consensus statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:193–203.

Goodwin PJ, Stambolic V, Lemieux J, Chen BE, Parulekar WR, Gelmon KA, et al. Evaluation of metformin in early breast cancer: a modification of the traditional paradigm for clinical testing of anti-cancer agents. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126:215–20.

Kim J, Lim W, Kim EK, Kim MK, Paik NS, Jeong SS, et al. Phase II randomized trial of neoadjuvant metformin plus letrozole versus placebo plus letrozole for estrogen receptor positive postmenopausal breast cancer (METEOR). BMC Cancer. 2014;14:170.

Jiralerspong S, Palla SL, Giordano SH, Meric-Bernstam F, Liedtke C, Barnett CM, et al. Metformin and pathologic complete responses to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in diabetic patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3297–302.

Peeters PJ, Bazelier MT, Vestergaard P, Leufkens HG, Schmidt MK, de Vries F, et al. Use of metformin and survival of diabetic women with breast cancer. Curr Drug Saf. 2013;8:357–63.

Niraula S, Dowling RJ, Ennis M, Chang MC, Done SJ, Hood N, et al. Metformin in early breast cancer: a prospective window of opportunity neoadjuvant study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;135:821–30.

Lega IC, Austin PC, Gruneir A, Goodwin PJ, Rochon PA, Lipscombe LL. Association between metformin therapy and mortality after breast cancer: a population-based study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3018–26.

He X, Esteva FJ, Ensor J, Hortobagyi GN, Lee MH, Yeung SC. Metformin and thiazolidinediones are associated with improved breast cancer-specific survival of diabetic women with HER2+ breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1771–80.

Goodwin PJ, Stambolic V. Obesity and insulin resistance in breast cancer–chemoprevention strategies with a focus on metformin. Breast. 2011;20:S31–5.

Bayraktar S, Hernadez-Aya LF, Lei X, Meric-Bernstam F, Litton JK, Hsu L, et al. Effect of metformin on survival outcomes in diabetic patients with triple receptor-negative breast cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:1202–11.

Hou G, Zhang S, Zhang X, Wang P, Hao X, Zhang J. Clinical pathological characteristics and prognostic analysis of 1,013 breast cancer patients with diabetes. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137:807–16.

Xiao Y, Zhang S, Hou G, Zhang X, Hao X, Zhang J. Clinical pathological characteristics and prognostic analysis of diabetic women with luminal subtype breast cancer. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:2035–45.

Martin-Castillo B, Vazquez-Martin A, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Menendez JA. Metformin and cancer: doses, mechanisms and the dandelion and hormetic phenomena. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1057–64.

Zhu P, Davis M, Blackwelder AJ, Bachman N, Liu B, Edgerton S, et al. Metformin selectively targets tumor-initiating cells in erbb2-overexpressing breast cancer models. Cancer Prevention Res. 2014;7:199–210.

Martin LA, Andre F, Campone M, Bachelot T, Jerusalem G. mTOR inhibitors in advanced breast cancer: Ready for prime time? Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39:742–52.

Shaw RJ, Cantley LC. Ras, PI(3)K and mTOR signalling controls tumour cell growth. Nature. 2006;441:424–30.

Steelman LS, Navolanic P, Chappell WH, Abrams SL, Wong EW, Martelli AM, et al. Involvement of Akt and mTOR in chemotherapeutic- and hormonal-based drug resistance and response to radiation in breast cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:3003–15.

Goodson 3rd WH, Luciani MG, Sayeed SA, Jaffee IM, Moore 2nd DH, Dairkee SH. Activation of the mTOR pathway by low levels of xenoestrogens in breast epithelial cells from high-risk women. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1724–33.

Santen RJ, Song RX, Masamura S, Yue W, Fan P, Sogon T, et al. Adaptation to estradiol deprivation causes up-regulation of growth factor pathways and hypersensitivity to estradiol in breast cancer cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;630:19–34.

Arpino G, Wiechmann L, Osborne CK, Schiff R. Crosstalk between the estrogen receptor and the HER tyrosine kinase receptor family: molecular mechanism and clinical implications for endocrine therapy resistance. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:217–33.

Ahmadieh H, Azar ST. Type 2 diabetes mellitus, oral diabetic medications, insulin therapy, and overall breast cancer risk. ISRN Endocrinol. 2013;2013:181240.

Arcidiacono B, Iiritano S, Nocera A, Possidente K, Nevolo MT, Ventura V, et al. Insulin resistance and cancer risk: an overview of the pathogenetic mechanisms. Exp Diabetes Res. 2012;2012:789174.

Arteaga CL, Sliwkowski MX, Osborne CK, Perez EA, Puglisi F, Gianni L. Treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer: current status and future perspectives. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:16–32.

Baselga J, Semiglazov V, van Dam P, Manikhas A, Bellet M, Mayordomo J, et al. Phase II randomized study of neoadjuvant everolimus plus letrozole compared with placebo plus letrozole in patients with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2630–7.

Acknowledgements

We all thank all the participants in the study, study personnel for their devoted work during data collection. We also would like to acknowledge Dr Choi for general support. The present research has been supported by Korean Breast Cancer Foundation. The funding resources had no role in the study design, data collection, analyses, data interpretation, writing the manuscript or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors have declared that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

HeeJK, SHA, JWL, and HwaJK conceived and designed the study. HK, SBL, HSP, GS, YL, BSK, JHY, BHS, and HeeJK acquired the data. HeeJK, HwaJK, and SBL performed analysis and interpretation. HeeJK and HK wrote the paper. HeeJK, HwaJK, SHA, HK, JWL, SBL, HSP, GS,YL, BSK, JHY, and BHS reviewed and corrected the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, H.J., Kwon, H., Lee, J.W. et al. Metformin increases survival in hormone receptor-positive, HER2-positive breast cancer patients with diabetes. Breast Cancer Res 17, 64 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-015-0574-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-015-0574-3