Abstract

Background

Both high hyperdiploidy (HeH) and the translocation t(9;22)(q34;q11) are recurrent abnormalities in childhood B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and both are used in current classification to define different genetic and prognostic subtypes of the disease. The coexistence of these two primary genetic aberrations within the same clone is very rare in children with ALL. Here we report a new case of a 17-year-old girl with newly diagnosed ALL and uncommon cytogenetic and clinical finding combining high hyperdiploidy and a cryptic BCR/ABL1 fusion and an inherited Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy detected during the induction treatment.

Results

High hyperdiploid karyotype 51,XX,+X,+4,+14,+17,+21 without apparent structural aberrations was detected by conventional cytogenetic analysis and multicolor FISH. A cryptic BCR/ABL1 fusion, which was caused by the insertion of part of the ABL1 gene into the 22q11 region, was proved in HeH clone by FISH, RT-PCR and CGH-SNP array. In addition, an abnormal FISH pattern previously described as the deletion of the 3′BCR region in some BCR/ABL1 positive cases was not proved in our patient.

Conclusion

A novel case of extremely rare childhood ALL, characterized by HeH and a cryptic BCR/ABL1 fusion, is presented and to the best of our knowledge described for the first time. The insertion of ABL1 into the BCR region in malignant cells is supposed. Clearly, further studies are needed to determine the genetic consequences and prognostic implications of these unusual cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pediatric B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BCP-ALL) is a heterogeneous disease on both the cytogenetic and genetic levels [1]. A number of acquired chromosomal aberrations have been identified in the bone marrow cells of children with ALL, which provide diagnostic and prognostic information that directly affects patient management [2].

The Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome, i.e., translocation t(9;22)(q34;q11), giving rise to the BCR/ABL1 fusion gene, is a rare finding in children with ALL, accounting for ~3% of cases, and is traditionally associated with a poor outcome [3]. However, implementation of tyrosine kinase inhibitors to standard therapy greatly improved the survival of children with Ph + ALL [4]. In a small number of ALL patients, the Ph chromosome is not detected by conventional cytogenetics, but the BCR/ABL1 fusion is present [5]. In these cases, the fusion either arises as a cryptic rearrangement or is masked within a complex karyotype and can only be detected by molecular cytogenetic and/or molecular genetic methods. On the contrary, high hyperdiploidy (HeH), defined as the presence of 51–67 chromosomes in the karyotype, is the most frequent cytogenetic finding in childhood ALL, occurring in 25%–30% of cases. It is characterized by a nonrandom gain of specific chromosomes and a clinically favorable prognosis [6],[7].

Although HeH is a common finding in childhood ALL, there are rare instances of high-hyperdiploid patients carrying other ALL-specific translocations, i.e., t(9;22)(q34;q11), t(12;21)(p13;q22), t(1;19)(q23;p13), and MLL rearrangements. These cases comprise 1%–4% of the patients with high-hyperdiploid ALL [8]. We present a patient with newly diagnosed ALL and a rare cytogenetic finding, combining HeH and an unusual BCR/ABL1 fusion caused by the insertion of part of the ABL1 gene into the 22q11 region. Moreover, the patient was diagnosed with an inherited neuropathy Charcot-Marie-Tooth syndrome during the antileukemic treatment.

Case presentation

A 17-year-old girl was diagnosed with common ALL (cALL) in January 2013 after experiencing one month of fatigue, bone pain at rest, and lymphocytosis in the peripheral blood (lymphocytes 86%). A complete blood count showed 11.3 × 109/L WBC, 86 g/L hemoglobin, and a platelet count of 42 × 109/L. Her bone marrow was infiltrated by lymphoblasts (96.8%) with an L1 morphology. Blasts had hyperdiploid DNA content (DNA index 1.089). Immunophenotypically blasts corresponded to cALL with aberrant expression of CD66c, high CD34 positivity and low expression of CD38 antigen. Immunophenotype was typical for BCR/ABL1 positivity [9]. BCR/ABL fusion gene was confirmed with multiplex RT-PCR.

The patient has been treated according to the EsPhALL 2010 protocol for BCR/ABL-positive ALL with a combination of chemotherapy and imatinib (Glivec). During induction, the patient developed very severe peripheral neurotoxicity with quadriparesis and paralytic ileus, which required major surgery with stoma. This critical clinical condition resulted in interruption of the chemotherapy treatment for two weeks. Surprisingly, the cause of this unexpected complication was inherited neuropathy Charcot-Marie-Tooth syndrome (CMT1A subtype), with a proven PMP22 mutation. Subsequently it was clear that the neurotoxicity was an abnormal reaction to Vincristine therapy and therefore further vinca alkaloid medication was contraindicated. At present, the patient is in continuous complete remission (18 months from the diagnosis) on maintenance chemotherapy with imatinib, she is after submerging of her stoma and her neurological status is improving.

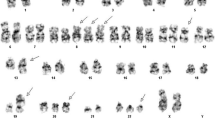

For the cytogenetic analyses, bone marrow cells were cultured for 24 hours without stimulation, and chromosomal preparations were made using standard techniques. In total, 25 metaphases were analyzed and the karyotypes were described according to An International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (ISCN 2013) [10].

To detect the BCR/ABL1 fusion gene, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed with commercially available locus-specific probes (Vysis LSI BCR/ABL Dual Color Dual Fusion Translocation Probe and Vysis LSI BCR/ABL ES Dual Color Translocation Probe; Abbott Molecular, Des Plaines, IL, USA). All available metaphases and 200 interphase nuclei were analyzed.

Other chromosomal aberrations were analyzed with multicolor FISH (mFISH) and comparative genomic hybridization based array (aCGH) using the 24X Cyte color kit (MetaSystems, Altlussheim, Germany) and an oligonucleotide CGH–single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array (BlueGnome, Cambridge, UK) respectively. Array results were confirmed by FISH with the appropriate bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) probes (BlueGnome). All techniques were done according to manufacturer’s recommendations.

The fusion transcript BCR/ABL1 was detected with reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR), which was performed according to Europe Against Cancer program protocol [11]. The amount of cDNA was normalized to the expression of housekeeping gene GUS as described previously [12].

An m-BCR/ABL1 fusion gene was detected with multiplex RT–PCR. Moreover, we found also the genomic breakpoint between the BCR and ABL1 genes (BCR intron 1/ABL1 intron 1). The karyotype was described as follows: 51,XX,+X,+4,+14,+17,+21[22]/46,XX[3]. However, FISH with the BCR/ABL Extra Signal and BCR/ABL Dual Fusion Probes detected the BCR/ABL1 fusion with an abnormal FISH signal pattern (1F2O1G), consistent with a breakpoint within m-BCR and the loss of the 3′BCR signal from der(9) in ten out of eleven metaphases and ~70% of the interphase nuclei (Figure 1). A detailed FISH signal analysis of the abnormal metaphases revealed the fusion signal to be located on apparently normal chromosome 22 and the ABL1 signal in the 9q34 region of two copies of chromosome 9. The expected deletion of the 3′BCR region (from the FISH results) was not detected by array CGH and BAC probes and only other chromosomal abnormalities were found, including trisomies of chromosomes X, 4, 14, 17, and 21, cryptic deletion of the short arm of chromosome 20 [del (20) (p12.1p12.1)] and submicroscopic amplification of the 22q11.22 region (Figure 1).

Results of molecular cytogenetic analysis. Multicolor FISH (A) and array CGH (B) showing trisomies of chromosomes X, 4, 14, 17 and 21 (A, B) and submicroscopic aberrations: deletion of chromosome 20 and amplification of chromosome 22 (B). BCR/ABL1 positive metaphase hybridized with BCR/ABL dual fusion (DF) probe demonstrating apparent loss of green 3′BCR signal, i.e. 1F2O1G FISH pattern (caused by the insertion of the ABL1 gene into the BCR region, thus entire BCR signal remained on chromosome 22) (C). FISH with BAC probes RP11-80O7 (orange) and RP11-400P21 (green) with evidence of normal finding of 22q11.23 region matching to 3′BCR locus (two orange signals) and deletion of 20p12.1 (one green signal) (D). Detailed view of array CGH result of chromosome 22 showing amplification of the 22q11.22 region and normal 22q11.23 region pattern (E).

Based on the cytogenetic and genetic results, it is clear that the BCR/ABL1 fusion in our patient arose from the submicroscopic insertion of part of the ABL1 gene into chromosome 22. It is based on the facts that: (1) no classical or variant Ph translocation was detected by conventional cytogenetic/mFISH; (2) loss of the 3′BCR region, although expected from interphase FISH signal pattern, was not confirmed by array CGH or by FISH with BAC probes for this region, i.e. entire BCR signal remained on chromosome 22 and was not translocated on chromosome 9; and (3) only the BCR/ABL1 fusion was proved at the RNA as well as DNA level, while the reciprocal ABL1/BCR fusion was not found by any of these approaches.

Our results show that only parallel cytogenetic, molecular cytogenetic, and molecular genetic analyses can provide detailed information about cryptic and prognostically significant aberrations that could not have been achieved with any of these techniques used independently. The metaphase FISH results were important for the correct interpretation of the interphase FISH findings, because only this analysis could identify the location of the BCR/ABL1 fusion on der(22). The current inclusion of array techniques into routine practice could lead us to reevaluate the real occurrence of deletions of either the 3′BCR or 5′ABL1 region in BCR/ABL1-positive cases (especially with cryptic insertions) previously described by FISH analyses.

Several patients with CML, or less frequently with ALL, have been reported with cryptic insertions of part of the BCR region into ABL1 at 9q34 or rarely of ABL1 into BCR at 22q11 [13],[14]. However, to our knowledge, this is the first published case of such an aberration in childhood high-hyperdiploid ALL with inherited Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy. In general, ALL-specific rearrangements are extremely rare in patients with HeH and it is difficult to identify the primary abnormality. In most cases (as in our patient), both aberrations were presented simultaneously in abnormal cells. However, few cases of HeH Ph-positive ALL have been published in the literature [15],[16], and these patients displayed not only a Ph-positive HeH clone, but also cells with 46 chromosomes and t(9;22)(q34;q11) as the sole abnormality, suggesting that the Ph chromosome was the primary aberration.

There is no difference in the gain of specific chromosomes (namely X, 4, 6, 8, 10, 14, 17, 18 a 21) between patients with high-hyperdiploid ALL and commonly encountered ALL aberrations, and those with high-hyperdiploid ALL. The only exception is the trisomy of chromosome 2, which was previously described as a quite frequent chromosome gain in patients with translocation t(9;22)(q34;q11) [6],[16]. However, trisomy of chromosome 2 was not found in our patient, nor was revealed as a frequent trisomy in six other currently described cases with Ph positive HeH ALL [8].

From a clinical perspective, patients with HeH and well-known translocations are considered to represent a biologically distinct subgroup, which may have independent prognostic implications [17]. From previously reported cases, it seems that the prognostic impact of the translocation could override the beneficial effect of HeH [17],[18]. However, brief follow-up period does not allow to assess any conclusion about the impact of this finding on prognosis in our patient nor to predict the effect of the inherited neuropathy.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a novel case of extremely rare childhood ALL, characterized by HeH and a cryptic BCR/ABL1 fusion, is presented and described for the first time and the insertion of ABL1 into the BCR region in malignant cells is supposed. Although several cases of childhood ALL with HeH and general ALL-specific aberrations have been published, the exact pathogenetic mechanisms of the disease in these patients have not been clarified. Clearly, further studies of these uncommon cases are necessary to determine the genetic consequences and real prognostic implications of these phenomena.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parents for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Authors’ contributions

LL performed FISH experiments, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. ZZ carried out mFISH/mBAND analysis and participated in interpretation of the data. HL performed and analyzed array CGH experiments. JZ and LH were responsible for molecular analysis. EM done the immunophenotypic analyses. EM carried out FISH analyses. JR performed conventional cytogenetic analysis. IR participated in interpretation of the data and supervision of the manuscript. LS and JS treated the patient, collected samples and provided patient’s data. KM supervised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Abbreviations

- BCP-ALL:

-

B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- CML:

-

Chronic myeloid leukemia

- HeH:

-

High hyperdiploidy

- FISH:

-

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- mFISH:

-

Multicolor FISH

- RT-PCR:

-

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- CGH-SNP array:

-

Comparative genomic hybridization-single nucleotide polymorphism array

- BAC probes:

-

Bacterial artificial chromosome probes

References

Moorman AV, Ensor HM, Richards SM, Chilton L, Schwab C, Kinsey SE, Vora A, Mitchell CD, Harrison CJ: Prognostic effect of chromosomal abnormalities in childhood B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: results from the UK Medical Research Council ALL97/99 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2010, 11: 429–438. 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70066-8

Harrison CJ: The genetics of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2000, 13: 427–439. 10.1053/beha.2000.0086

Carroll WL, Raetz EA: Clinical and laboratory biology of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr 2012, 160: 10–18. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.08.006

Schultz KR, Carroll A, Heerema NA, Bowman WP, Aledo A, Slayton WB, Sather H, Devidas M, Zheng HW, Davies SM, Gaynon PS, Trigg M, Rutledge R, Jorstad D, Winick N, Borowitz MJ, Hunger SP, Carroll WL, Camitta B: Long-term follow-up of imatinib in pediatric Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Children’s Oncology Group Study AALL0031. Leukemia 2014, 28: 1467–1471. 10.1038/leu.2014.30

van Rhee F, Kasprzyk A, Jamil A, Dickinson H, Lin F, Cross NC, Galvin MC, Goldman JM, Secker-Walker LM: Detection of the BCR-ABL gene by reverse transcription/polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization in a patient with Philadelphia chromosome negative acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol 1995, 90: 225–228. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1995.tb03408.x

Paulsson K, Johansson B: High hyperdiploid childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2009, 48: 637–660. 10.1002/gcc.20671

Zemanova Z, Michalova K, Sindelarova L, Smosek P, Brezinova J, Ransdorfova S, Vavra V, Dohnalova A, Stary J: Prognostic value of structural chromosomal rearrangements and small cell clones with high hyperdiploidy in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Res 2005, 29: 273–281. 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.07.004

Paulsson K, Forestier E, Andersen MK, Autio K, Barbany G, Borgström G, Cavelier L, Golovleva I, Heim S, Heinonen K, Hovland R, Johannsson JH, Kjeldsen E, Nordgren A, Palmqvist L, Johansson B: High modal number and triple trisomies are highly correlated favorable factors in childhood B-cell precursor high hyperdiploid acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated according to the NOPHO ALL 1992/2000 protocols. Haematologica 2013, 98: 1424–1432. 10.3324/haematol.2013.085852

Hrusak O, Porwit-MacDonald A: Antigen expression patterns reflecting genotype of acute leukemias. Leukemia 2002, 16: 1233–1258. 10.1038/sj.leu.2402504

Shaffer LG, McGowan-Jordan J, Schmidt M: ISCN 2013: An International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature. S. Karger, Basel; 2013.

Gabert J, Beillard E, van der Velden VH, Bi W, Grimwade D, Pallisgaard N, Barbany G, Cazzaniga G, Cayuela JM, Cavé H, Pane F, Aerts JL, De Micheli D, Thirion X, Pradel V, González M, Viehmann S, Malec M, Saglio G, van Dongen JJ: Standardization and quality control studies of ‘real time’ quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of fusion gene transcripts for residual disease detection in leukemia a Europe Against Cancer program. Leukemia 2003, 17: 2318–2357. 10.1038/sj.leu.2403135

Beillard E, Pallisgaard N, van der Velden VH, Bi W, Dee R, van der Schoot E, Delabesse E, Macintyre E, Gottardi E, Saglio G, Watzinger F, Lion T, van Dongen JJ, Hokland P, Gabert J: Evaluation of candidate control genes for diagnosis and residual disease detection in leukemic patients using ‘real time’ quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RQ PCR) a Europe against cancer program. Leukemia 2003, 17: 2474–2486. 10.1038/sj.leu.2403136

Primo D, Tabernero MD, Rasillo A, Sayagués JM, Espinosa AB, Chillón MC, Garcia-Sanz R, Gutierrez N, Giralt M, Hagemeijer A, San Miguel JF, Orfao A: Patterns of BCR/ABL gene rearrangements by interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in BCR/ABL + leukemias: incidence and underlying genetic abnormalities. Leukemia 2003, 17: 1124–1129. 10.1038/sj.leu.2402963

Robinson HM, Martineau M, Harris RL, Barber KE, Jalali GR, Moorman AV, Strefford JC, Broadfield ZJ, Cheung KL, Harrison CJ: Derivative chromosome 9 deletions are a significant feature of childhood Philadelphia chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Leukemia 2005, 19: 564–571.

Heerema NA, Harbott J, Galimberti S, Camitta BM, Gaynon PS, Janka-Schaub G, Kamps W, Basso G, Pui CH, Schrappe M, Auclerc MF, Carroll AJ, Conter V, Harrison CJ, Pullen J, Raimondi SC, Richards S, Riehm H, Sather HN, Shuster JJ, Silverman LB, Valsecchi MG, Aricò M: Secondary cytogenetic aberrations in childhood Philadelphia chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia are nonrandom and may be associated with outcome. Leukemia 2004, 18: 693–702. 10.1038/sj.leu.2403324

Chilton L, Buck G, Harrison CJ, Ketterling RP, Rowe JM, Tallman MS, Goldstone AH, Fielding AK, Moorman AV: High hyperdiploidy among adolescents and adults with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL): cytogenetic features, clinical characteristics and outcome. Leukemia 2014, 28: 1511–1518. 10.1038/leu.2013.379

Moorman AV, Richards SM, Martineau M, Cheung KL, Robinson HM, Jalali GR, Broadfield ZJ, Harris RL, Taylor KE, Gibson BE, Hann IM, Hill FG, Kinsey SE, Eden TO, Mitchell CD, Harrison CJ: Outcome heterogeneity in childhood high-hyperdiploid acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2003, 102: 2756–2762. 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1128

Forestier E, Johansson B, Gustafsson G, Borgström G, Kerndrup G, Johannsson J, Heim S: Prognostic impact of karyotypic findings in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a Nordic series comparing two treatment periods. For the Nordic Society of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology (NOPHO) Leukaemia Cytogenetic Study Group. Br J Haematol 2000, 110: 147–153. 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02153.x

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Czech Ministry of Health RVO-VFN64165, and IGA NT14350-3 and the Czech Science Foundation GACR-P302/12/G157.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Lizcova, L., Zemanova, Z., Lhotska, H. et al. An unusual case of high hyperdiploid childhood ALL with cryptic BCR/ABL1 rearrangement. Mol Cytogenet 7, 72 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13039-014-0072-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13039-014-0072-9