Abstract

Background

The promotion of mental health among children and adolescents is a public health imperative worldwide, and schools have been proposed as the primary and targeted settings for mental health promotion for students in grades K-12. This review sought to provide a comprehensive understanding of key factors involved in models of school education contributing to student mental health development, interrelationships among these factors and the cross-cultural differences across nations and societies.

Methods

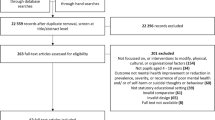

This scoping review followed the framework of Arksey and O’Malley and holistically reviewed the current evidence on the potential impacts of school-related factors or school-based interventions on student mental health in recent 5 years based on the PubMed, Web of Science, Embase and PsycExtra databases.

Results/findings

After screening 558 full-texts, this review contained a total of 197 original articles on school education and student mental health. Based on the five key factors (including curriculum, homework and tests, physical activities, interpersonal relationships and after-school activities) identified in student mental development according to thematic analyses, a multi-component school educational model integrating academic, social and physical factors was proposed so as to conceptualize the five school-based dimensions for K-12 students to promote student mental health development.

Conclusions

The lessons learned from previous studies indicate that developing multi-component school strategies to promote student mental health remains a major challenge. This review may help establish appropriate school educational models and call for a greater emphasis on advancement of student mental health in the K-12 school context among different nations or societies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, mental health conditions among children and adolescents have received considerable attention as a public health concern. Globally about 10–20% of children and adolescents experience mental health problems [1, 2], and mental health problems in early life may have the potential for long-term adverse consequences [3, 4]. In 2019, the World Health Organization has pointed out that childhood and adolescence are critical periods for the acquisition of socio-emotional capabilities and for prevention of mental health problems [5]. A comprehensive multi-level solution to child mental health problems needs to be put forward for the sake of a healthier lifestyle and environment for future generations.

The school is a unique resource to help children improve their mental health. A few generations ago, schools’ priority was to teach the traditional subjects, such as reading, writing, and arithmetic. However, children are now spending a large amount of time at school where they learn, play and socialize. For some students, schools have a positive influence on their mental health. While for others, schools can present as a considerable source of stress, worry, and unhappiness, and hinder academic achievement [2]. According to Greenberg et al., today’s schools need to teach beyond basic skills (such as reading, writing, and counting skills) and enhance students’ social-emotional competence, characters, health, and civic engagement [6]. Therefore, universal mental health promotion in school settings is recognized to be particularly effective in improving students’ emotional well-being [2, 7].

Research evidence over the last two decades has shown that schools can make a difference to students’ mental health [8]. Previous related systematic reviews or meta-analyses focused on the effects of a particular school-based intervention on child mental health [9, 10] and answered a specific question with available research, however, reviews covering different school-related factors or school-based interventions are still lacking. An appropriate model of school education requires the combination of different school-related factors (such as curriculum, homework, and physical activities) and therefore needs to focus on multiple primary outcomes. Thus, we consider that a scoping review may be more appropriate to help us synthesize the recent evidence than a systematic review or meta-analysis, as the wide coverage and the heterogeneous nature of related literature focusing on multiple primary outcomes are not amenable to a more precise systematic review or meta-analysis [11]. To the best of our knowledge, this review is among the first to provide a comprehensive overview of available evidence on the potential impacts of multiple school-related factors or school-based interventions on student mental health, and identify school-related risk/protective factors involved in the development of mental health problems among K-12 students, and therefore, to help develop a holistic model of K-12 education.

Methods

Design

A scoping review was systematically conducted following the methodological framework of Arksey and O'Malley [12]: defining the research question; identifying relevant studies; study selection; data extraction; and summarizing and reporting results. The protocol for this review was specified in advance and submitted for registration in the PROSPERO database (Reference number, CRD42019123126).

Defining the research question (stage 1)

For this review, we sought to answer the following questions:

-

1.

What is known from the existing literature on the potential impacts of school-related factors or school-based interventions on student mental health?

-

2.

What are the interrelationships among these factors involved in the school educational process?

-

3.

What are the cross-cultural differences in K-12 education process across nations and societies?

Identifying relevant studies (stage 2)

The search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science and Embase electronic databases, and the dates of the published articles included in the search were limited to the last 5 years until 23 March 2021. The PsycExtra database was also searched to identify relevant evidence in the grey literature [13]. In recent 5 years, mental disorders among children and adolescents have increased at an alarming rate [14, 15] and relevant policies calling for a greater role of schools in promoting student mental health have been issued in different countries [16,17,18], making educational settings at the forefront of the prevention initiative globally. Therefore, limiting research source published in the past 5 years was pre-defined since these publications reflected the newest discoveries, theories, processes, or practices. Search terms were selected based on the eligibility criteria and outcomes of interest were described as follows (Additional file 1: Table S1). The search strategy was peer-reviewed by the librarian of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine.

Study selection (stage 3)

T.Y. and Y.J. independently identified relevant articles by screening the titles, reviewing the abstracts and full-text articles. If any disagreement arises, the disagreement shall be resolved by discussion between the two reviewers and a third reviewer (J. X.).

Inclusion criteria were (1) according to the study designs: only randomized controlled trials (RCT)/quasi-RCT, longitudinal and cross-sectional studies; (2) according to the languages: articles only published in English or Chinese; (3) according to the ages of the subjects: preschoolers (3.5–5 years of age), children (6–11 years of age) and adolescents (12–18 years of age); and (4) according to the study topics: only articles examining the associations between factors involved in the school education and student mental health outcomes (psychological distress, such as depression, anxiety, stress, self-injury, suicide; and/or psychological well-being, such as self-esteem, self-concept, self-efficacy, optimism and happiness) in educational settings. Exclusion criteria: (1) Conference abstracts, case report/series, and descriptive articles were excluded due to overall quality and reliability. (2) Studies investigating problems potentially on a causal pathway to mental health disorders but without close associations with school education models (such as problems probably caused by family backgrounds) were excluded. (3) Studies using schools as the recruitment places but without school-related topics were also excluded.

Data extraction (stage 4)

T.Y. and Y.J., and X.G., Y. Z., H.H. extracted data from the included studies using a pre-defined extraction sheet. Researchers extracted the following information from each eligible study: study background (name of the first author, publication year, and study location), sample characteristics (number of participants, ages of participants, and sex proportion), design [intervention (RCT or quasi-RCT), or observational (cross-sectional or longitudinal) study], and instruments used to assess exposures in school settings and mental health outcomes. For intervention studies (RCTs and quasi-RCTs), we also extracted weeks of intervention, descriptions of the program, duration and frequency. T.Y. reviewed all the data extraction sheets under the supervision of J. X.

Summarizing and reporting the results (stage 5)

Results were summarized and reported using a narrative synthesis approach. Studies were sorted according to (a) factors/exposures associated with child and adolescent mental health in educational settings, and (b) components of school-based interventions to facilitate student mental health development. Key findings from the studies were then compared, contrasted and synthesized to illuminate themes which appeared across multiple investigations.

Results

Search results and characteristics of the included articles

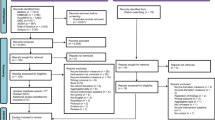

The search yielded 25,338 citations, from which 558 were screened in full-text. Finally, a total of 197 original articles were included in this scoping review: 72 RCTs (including individually randomized and cluster-randomized trials), 27 quasi-RCTs, 29 longitudinal studies and 69 cross-sectional studies (Fig. 1 for details). Based on thematic analyses, the included studies were analyzed and thematically grouped into five overarching categories based on the common themes in the types of intervention programs or exposures in the school context: curriculum, homework and tests, interpersonal relationships, physical activity and after-school activities. Table 1 provided a numerical summary of the characteristics of the included articles. The 197 articles included data from 46 countries in total, covering 24 European countries, 13 Asian countries, 4 American countries, 3 African countries, and 2 Oceanian countries. Most intervention studies were conducted in the United States of America (n = 16), followed by Australia (n = 11) and the United Kingdom (n = 11). Most observational studies were conducted in the United States of America (n = 19), followed by China (n = 15) and Canada (n = 8). Figure 2 illustrated the geographical distribution of the included studies. Further detailed descriptions of the intervention studies or observational studies were provided in Additional file 1: Tables S2 and S3, respectively.

Curriculum

The association between school curriculum and student mental health was investigated in four cross-sectional studies. Mathematics performance was found to be adversely associated with levels of anxiety or negative emotional responses among primary school students [19]. However, in middle schools, difficulties and stressors students may encounter in learning academic lessons (such as difficulties/stressors in taking notes and understanding teachers’ instructions) could contribute to lowered self-esteem [20] and increased suicidal ideation or attempts [21]. Innovative integration of different courses instead of the traditional approach of teaching biology, chemistry, and physics separately, could improve students’ self-concept [22].

To promote student mental health, 64 intervention studies were involved in innovative curricula integrating different types of competencies, including social emotional learning (SEL), mindfulness-intervention, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)-based curriculum, life skills training, stress management curriculum, and so on (Fig. 3). Curricula focusing on SEL put an emphasis on the development of child social-emotional skills such as managing emotions, coping skills and empathy [23], and showed positive effects on depression, anxiety, stress, negative affect and emotional problems [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37], especially in children with psychological symptoms [24] and girls [23, 27], as well as increased prosocial behaviors [38], self-esteem [39,40,41,42] and positive affect [43]. However, four programs reported non-significant effects of SEL on student mental health outcomes [44,45,46,47], while two programs demonstrated increased levels of anxiety [48] and a reduction of subjective well-being [49] at post-intervention. Mindfulness-based curriculum showed its potential to endorse positive outcomes for youth including reduced emotional problems and negative affect [50,51,52,53,54,55,56] as well as increased well-being and positive emotions [51, 52, 57,58,59,60], especially among high-risk children with emotional problems or perceived stress before interventions [50, 53]. However, non-significant effects were also reported in an Australian study in secondary schools [61]. Curricula based on CBT targeted children at risk or with early symptoms of mental illness [62,63,64,65,66,67], or all students regardless of symptom levels as a universal program [68,69,70], and could impose a positive effect on self-esteem, well-being, distress, stress and suicidality. However, a universal CBT trial in Swedish primary schools found no evidence of long-term effects of such program on anxiety prevention [71]. Five intervention studies based on life-skill-training were found to be effective in promoting self-efficacy [72, 73], self-esteem [73, 74], and reducing depression/anxiety-like symptoms [72, 75, 76]. Courses covering stress management skills have also been reported to improve life satisfaction, increase happiness and decrease anxiety levels among students in developing countries [77,78,79]. In practice, innovative teaching forms such as the game play [67, 80, 81] and outdoor learning [82, 83] embedded in the traditional classes could help address the mental health and social participation concerns for children and youth. Limited evidence supported the mental health benefits of resilience-based curricula [84,85,86], which deserve further studies.

Harvest plots for overview of curriculum-based intervention studies, grouped by different types of curriculum-based interventions. The height of the bars corresponded to the sample sizes on a logarithmic scale of each study. Red bars represented positive effects of interventions on student mental health outcomes, grey bars represented non-significant effects on student mental health outcomes, and black bars represented negative effects on student mental health outcomes

Large cluster-randomized trials utilizing multi-component whole-school interventions which involves various aspects of school life (curriculum, interpersonal relationships, activities), such as the Strengthening Evidence base on scHool-based intErventions for pRomoting adolescent health (SEHER) program in India and the Together at School program in Finland, have been proved to be beneficial for prevention from depression [87,88,89] and psychological problems [90].

Homework and tests

Homework

The association between homework and psychological ill-being outcomes was investigated in four cross-sectional studies and one longitudinal study. Incomplete homework and longer homework durations were associated with a higher risk of anxiety symptoms [91, 92], negative emotions [93,94,95] and even psychological distress in adulthood [96].

Tests

Innumerable exams during the educational process starting from primary schools may lead to increased anxiety and depression levels [97, 98], particularly among senior students preparing for college entrance examinations [99]. Students with higher test scores had a lower probability to have emotional and behavioral problems [100], in comparison with students who failed examinations [93, 101]. Depression and test anxiety were found to be highly correlated [102]. In terms of psychological well-being outcomes, findings were consistent in the negative associations between student test anxiety and self-esteem/life-satisfaction levels [103, 104]. Regarding intervention studies, adolescent students at a high risk of test anxiety benefited from CBT or attention training by strengthening sense of control and meta-cognitive beliefs [105, 106]. However, more knowledge about the criteria for an upcoming test was not related to anxiety levels during lessons [107].

Interpersonal relationships

School-based interpersonal (student–student or student–teacher) relationships are also important to student mental health. Low support from schoolmates/teachers and negative interpersonal events were reported to be associated with psychosomatic health complaints [108,109,110,111,112,113]. In contrast, positive interpersonal relationships in schools could promote emotional well-being [114,115,116,117] and reduce depressive symptoms in students [118,119,120].

Student–teacher relationships

Negative teaching behaviors were associated with negative affect [121, 122] and low self-efficacy [123] among primary and high school students. Student–teacher conflicts at the beginning of the school year were associated with higher anxiety levels in students at the end of the year, and high-achieving girls were most susceptible to such negative associations [124]. Higher levels of perceived teachers’ support were correlated with decreased risks of depression [125], mental health problems [126] as well as increased positive affect [127, 128] and improved mental well-being [129, 130]. Better student–teacher relationships were positively associated with self-esteem/efficacy [131], while negatively associated with the risks of adolescents’ externalizing behaviors [132] among secondary school students. Longitudinal studies demonstrated that high intimacy levels between students and teachers were correlated with reduced emotional symptoms [133] and increased life-satisfaction among students [134]. In addition, more respect to teachers in 10th grade students was associated with higher self-efficacy and lower stress levels 1 year later [135].

A growing body of research focused on the issue of how to increase positive interactions between teachers and students in teaching practices. Actually, interventions on improving teaching skills to promote a positive classroom atmosphere could potentially benefit children, especially those experiencing a moderate to high level of risks of mental health problems [136, 137].

Student–student relationships

Findings were consistent in considering the positive peer relationship as a protective factor against internalizing and externalizing behaviors [138,139,140,141,142], depression [143,144,145], anxiety [146], self-harm [147] and suicide [148], and as a favorable factor for positive affect [149, 150], increased happiness [151], self-efficacy [152], optimism [153, 154] and mental well-being [155]. In contrast, peer-hassles, friendlessness, negative peer-beliefs, peer-conflicts/isolation and peer-rejection, have been identified in the development of psychological distress among students [141, 143, 149, 156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165].

As schools and classrooms are common settings to build peer relationships, student social skills to enhance the student–student relationship can be incorporated into school education. Training of interpersonal skills among secondary school students with depressive symptoms appeared to be effective in decreasing adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms [166]. In addition, recent studies also identified the effectiveness of small-group learning activities in the cognitive development and mental health promotion among students [87,88,89,90, 167].

Physical activity in school

Moderate-to-high-intensity physical activity during school days has been confirmed to benefit children and adolescents in relation to various psychosocial outcomes, such as reduced symptoms of depression [168], emotional problems [169] and mental distress [170] as well as improved self-efficacy [171] and mental well-being [172, 173]. In addition, participation in physical education (PE) at least twice a week was significantly associated with a lower likelihood of suicidal ideation and stress [174].

A variety of school‐based physical activity interventions or lessons have been proposed in previous studies to promote physical activity levels and psychosocial fitness in students, including integrating physical activities into classroom settings [175,176,177,178], assigning physical activity homework [178], physically-active academic lessons [179, 180] as well as an obligation of ensuring the participation of various kinds of sports (such as aerobic exercises, resistance exercises, yoga) in PE lessons [181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192]. Although the effectiveness of these proposed physical activity interventions was not consistent, physical education is suggested to implement sustainably as other academic courses with special attention.

After-school activities

Several cross-sectional studies have synthesized evidence on the positive effects of leisure-time physical activity against student depression, anxiety, stress, and psychological distress [193,194,195,196,197,198,199]. Extracurricular sport participation (such as sports, dance, and martial arts) could foster perceived self-efficacy, self-esteem, improve mental health status [200,201,202,203], and reduce emotional problems [204] and depressive symptoms [205]. Participation in team sports was more strongly related to beneficial mental health outcomes than individual sports, especially in high school girls [199]. Other forms of organized activities, such as youth organizations and arts, have also been demonstrated to benefit self-esteem [201], self-worth [206], satisfaction with life and optimism [207, 208].

However, different types of after-school activities may result in different impacts on student mental health. Previous studies demonstrated that students participating in after-school programs of yoga or sports had better well-being and self-efficacy [209], and decreased levels of anxiety [210] and negative mood [211], while another study showed that the after-school yoga program induced no significant changes in levels of depression, anxiety and stress among students [212]. Inconsistent findings on the effects of participation in art activities on student mental health were also reported [213, 214]. Another study also highlighted the benefits of after-school clubs, demonstrating an improvement in socio-emotional competencies and emotional status, and sustained effects at 12-month follow-up [215].

Discussion

Based on the potential importance of the five school-based factors identified in student mental development, a multi-component school educational model is therefore proposed to conceptualize the five school-based dimensions (including curriculum, homework and tests, interpersonal relationships, physical activity, and after-school activities) for K-12 students to promote their mental health (Fig. 4). The interrelationships among the five dimensions and cross-cultural comparisons are further discussed as follows in a holistic way.

Comprehensive understanding of K-12 school educational models: the reciprocal relationships among factors

Students’ experiences in the school educational context are dynamic processes which englobe a variety of educational elements (such as curriculum, homework, tests) and social elements (such as interpersonal relationships and social activities in schools). Based on the educational model proposed in this review, these educational/social elements are closely related and interact with each other, which play an important role in students’ psychosocial development.

Being aware of this, initiatives aimed to improve student social and emotional competencies may certainly impact student psychological well-being, at least in part, in a way of developing supportive relationships between teachers-students or between peers [35, 89]. On the other hand, the enhancement of interpersonal relationships at school could serve as a potent source of motivation for student academic progress so as to further promote psychological well-being [131, 132]. In addition, school education reforms intended to provide pupils with more varied teaching and learning practices to promote supportive interpersonal relationships between students and teachers or between peers, such as education programs outside the classroom [82], cooperative learning [167] and adaptive classroom management [136, 137], have also been advocated among nations recently.

Our findings also suggested that participation in non-academic activities was an important component of positive youth development. Actually, these school-based activities in different contexts also require teacher–student interactions or peer interactions. Social aspects of physical activities have been proposed to strengthen relationship-building and other interpersonal skills that may additionally protect students against the development of mental health problems [130, 203]. Among various types of sports, team sports seemed to be associated with more beneficial outcomes compared with individual sports due to the social aspect of being part of a team [194, 199]. Participation in music, student council, and other clubs/organizations may also provide students with frequent connections with peers, and opportunities to build relationships with others that share similar interests [201]. Further, frequent and supportive interactions with teachers and peers in sports and clubs may promote student positive views of the self and encourage their health-promoting behaviors (such as physical activities).

However, due to increasing academic pressure, children have to spend a large amount of time on academic studies, and inevitably displace time on sleep, leisure, exercises/sports, and extracurricular activities [92]. Although the right amount of homework may improve school achievements [216] and higher test scores may help prevent students from mental distress [100,101,102], over-emphasis on academic achivements may lead to elevated stress levels and poor health outcomes ultimately. The anxiety specifically related to academic achievement and test-taking at school was frequently reported among students who felt pressured and overwhelmed by the continuous evaluation of their academic performance [98, 103, 104]. In such high-pressure academic environments, strategies to alleviate the levels of stress among students should be incorporated into intervention efforts, such as stress management skill training [77,78,79], CBT-based curriculum [62, 64, 66, 105], and attention training [106]. Therefore, school supportive policies that allow students continued access to various non-academic activities as well as improve their social aspect of participation may be one fruitful avenue to promote student well-being.

Cross-cultural differences in K-12 educational models among different nations and societies

As we reviewed above, heavy academic burden exists as an important school-related stressor for students [91, 92, 94,95,96], probably due to excessive examinations [97,98,99] and unsatisfactory academic performance [100,101,102]. Actually, extrinsic cultural factors significantly impact upon student academic burden. In most countries, college admission policies affect the entire ecological system of K-12 education, because success in life or careers is determined by examination performance to a large extent [217]. The impacts of heavy academic burden may be greatest in Asian cultures where more after-school time of students is spent on homework, exam preparations, and extracurricular classes for academic improvement (such as in Korea, Japan, China and Singapore) [92, 95, 218]. As a consequence, the high proportion of adolescents fall in the “academic burnout group” in Asian countries [219], which highlights the need to take further measures to combat the issue. As an issue of concern, the “double reduction” policy has been implemented nationwide in China since 2021, being aimed to relieve students of excessive study burden, and the effects of the policy are anticipated but remain unknown up to now.

Other factors such as school curriculum and extra-curricular commitments, vary among societies and nations and may explain the cross-cultural differences in educational models [220]. For example, in Finland, the primary science subject is as important as mathematics or reading, while Chinese schools often lack time to arrange a sufficient number of science courses [221], which could be explained by different educational traditions of the two countries. In addition, approximately 75% of high schools in Korea failed to implement national curriculum guidelines for physical education (150 min/week), instead replacing that time with self-guided study to prepare for university admission exams [174]. In terms of the arrangement of the after-school time, Asian students spend most of their after-school time on private tutoring or doing homework [222], 2–3 times longer than the time spent by adolescents in most western countries/cities [92]. However, according to our analyses and summaries, most intervention studies targeting the improvement of mental health of students by school education were conducted in western countries (Fig. 2), suggesting that special attention needs to be paid to the students’ mental health issue on campus, especially in countries where students have heavy study-loads. Merits of the different educational traditions also need to be considered in the designs of educational models among different countries.

Strengths and limitations

This study focuses on an interdisciplinary topic covering the fields of developmental behavioral pediatrics and education, and the establishment of appropriate school educational models is teamwork involving multiple disciplines including pediatrics, prevention, education, services and policy. Although there are lots of studies focusing on a particular factor in school educational processes to promote student mental health, comprehensive analysis/understanding on multi-component educational model is lacking, which is important and urgently needed for the development of multi-dimensional educational models/strategies. Therefore, we included a wide range of related studies, summarized a comprehensive understanding of the evidence base, and discussed the interrelationships among the components/factors of school educational models and the cross-cultural gaps in K-12 education across different societies, which may have significant implications for future policy-making.

Some limitations also exist and are worth noting. First, this review used the method of the scoping review which adopted a descriptive approach, rather than the meta-analysis or systematic review which provided a rigorous method of synthesizing the literature. Under the subject (appropriate school education model among K-12 students) of this scoping review, multiple related topics (including curriculum, homework and tests, physical activities, interpersonal relationships and after-school activities) were included rather than one specific topic. Therefore, we consider that the method of the scoping-review is appropriate, given that the aim of this review is to chart or map the available literature on a given subject rather than answering a specific question by providing effect sizes across multiple studies. Second, we limited the study search within recent 5 years. Although we consider that the fields involved in this scoping review change quickly with the acquisition of new knowledge/information in recent 5 years, limiting the literature search within recent 5 years may make us miss some related but relatively old literature. Third, we only included studies disseminated in English or Chinese, which may limit the generalizability of our results to other non-English/Chinese speaking countries.

Conclusion

This scoping review has revealed that the K-12 schools are unique settings where almost all the children and adolescents can be reached, and through which existing educational components (such as curriculum, homework and tests, physical activities, interpersonal relationships and after-school activities) can be leveraged and integrated to form a holistic model of school education, and therefore to promote student mental health. In future, the school may be considered as an ideal setting to implement school-based mental health interventions. Our review suggests the need of comprehensive multi-component educational model, which involves academic, social and physical factors, to be established to improve student academic achievement and simultaneously maintain their mental health.

However, questions still remain as to what is optimal integration of various educational components to form the best model of school education, and how to promote the wide application of the appropriate school educational model. Individual differences among students/schools and cross-cultural differences may need to be considered in the model design process.

Availability of data and materials

The data analysed in this review are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- CBT:

-

Cognitive behavioral therapy

- PE:

-

Physical education

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- SEL:

-

Social emotional learning

References

Kieling C, Baker-Henningham H, Belfer M, Conti G, Ertem I, Omigbodun O, et al. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet. 2011;378(9801):1515–25.

O’Reilly M, Svirydzenka N, Adams S, Dogra N. Review of mental health promotion interventions in schools. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(7):647–62.

Garner AS, Shonkoff JP. Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: translating developmental science into lifelong health. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e224–31.

Gleason MM, Goldson E, Yogman MW, Council On Early C, Committee On Psychosocial Aspects Of C, Family H, et al. Addressing early childhood emotional and behavioral problems. Pediatrics. 2016;138(6):e20163025.

World Health Organization. Adolescent mental health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

Cristovao AM, Candeias AA, Verdasca J. Social and emotional learning and academic achievement in portuguese schools: a bibliometric study. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1913.

O’Mara L, Lind C. What do we know about school mental health promotion programmes for children and youth? Adv Sch Ment Health Promot. 2013;6:203–24.

Langford R, Bonell CP, Jones HE, Pouliou T, Murphy SM, Waters E, et al. The WHO Health Promoting School framework for improving the health and well-being of students and their academic achievement. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014(4):Cd008958.

Franklin C, Kim JS, Beretvas TS, Zhang A, Guz S, Park S, et al. The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions delivered by teachers in schools: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2017;20(3):333–50.

Werner-Seidler A, Perry Y, Calear AL, Newby JM, Christensen H. School-based depression and anxiety prevention programs for young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;51:30–47.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Adesanya EI, Schonmann Y, Hayes JF, Mathur R, Mulick AR, Rayner L, et al. Risk factors for mental illness in adults with atopic eczema or psoriasis: protocol for a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e038324-e.

Perou R, Bitsko RH, Blumberg SJ, Pastor P, Ghandour RM, Gfroerer JC, et al. Mental health surveillance among children—United States, 2005–2011. MMWR. 2013;62(Suppl; May 16, 2013):1–35.

Bitsko RH, Claussen AH, Lichtstein J, Black LJ, Everett Jones S, Danielson MD, et al. Mental health surveillance among children—United States, 2013–2019. MMWR. 2022;71(Suppl-2):1–42.

Department of Health and Social Care. Department for Education Transforming children and young people's mental health provision: a Green Paper 2017. https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/transformingchildren-and-young-peoples-mental-health-provision-a-green-paper. Accessed 04 Dec 2017.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adolescent health: what works in schools 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/whatworks/what-works-safe-and-supportive-environments.htm. Accessed 03 Feb 2020.

National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Healthy China initiative—action plan for mental health of children and adolescents (2019–2022). 2019. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/dongt/201912/0f680d618ccc45e586e7ae9cf1875891.shtml. Accessed 26 Dec 2019.

Rodriguez S, Regueiro B, Pineiro I, Valle A, Sanchez B, Vieites T, et al. Success in mathematics and academic wellbeing in primary-school students. Sustainability. 2020;12(9):3796.

Holopainen L, Waltzer K, Hoang N, Lappalainen K. The relationship between students’ self-esteem, schoolwork difficulties and subjective school well-being in finnish upper-secondary education. Int J Educ Res. 2020;104:101688.

Nagamitsu S, Mimaki M, Koyanagi K, Tokita N, Kobayashi Y, Hattori R, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of suicidality in Japanese adolescents: results from a population-based questionnaire survey. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20(1):467.

Jansen M, Schroeders U, Luedtke O, Marsh HW. The dimensional structure of students’ self-concept and interest in science depends on course composition. Learn Instr. 2019;60:20–8.

Dowling K, Simpkin AJ, Barry MM. A cluster randomized-controlled trial of the mindout social and emotional learning program for disadvantaged post-primary school students. J Youth Adolesc. 2019;48(7):1245–63.

Burckhardt R, Manicavasagar V, Batterham PJ, Hadzi-Pavlovic D. A randomized controlled trial of strong minds: a school-based mental health program combining acceptance and commitment therapy and positive psychology. J Sch Psychol. 2016;57:41–52.

Johnstone KM, Middleton T, Kemps E, Chen J. A pilot investigation of universal school-based prevention programs for anxiety and depression symptomology in children: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychol. 2020;76(7):1193–216.

Bono G, Mangan S, Fauteux M, Sender J. A new approach to gratitude interventions in high schools that supports student wellbeing. J Posit Psychol. 2020;15(5):657–65.

Maalouf FT, Alrojolah L, Ghandour L, Afifi R, Dirani LA, Barrett P, et al. Building emotional resilience in youth in Lebanon: a school-based randomized controlled trial of the FRIENDS intervention. Prev Sci. 2020;21(5):650–60.

Humphrey N, Panayiotou M. Bounce Back: randomised trial of a brief, school-based group intervention for children with emergent mental health difficulties. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;31:205–10.

Ab Ghaffar SF, Mohd Sidik S, Ibrahim N, Awang H, Gyanchand Rampal LR. Effect of a school-based anxiety prevention program among primary school children. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(24):4913.

Garaigordobil M, Jaureguizar J, Bernarás E. Evaluation of the effects of a childhood depression prevention program. J Psychol. 2019;153(2):127–40.

Zhu X, Shek DTL. Impact of a positive youth development program on junior high school students in mainland China: a pioneer study. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;114:105022.

Flynn D, Joyce M, Weihrauch M, Corcoran P. Innovations in practice: dialectical behaviour therapy—skills training for emotional problem solving for adolescents (DBT STEPS-A): evaluation of a pilot implementation in Irish post-primary schools. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2018;23(4):376–80.

Young JF, Jones JD, Sbrilli MD, Benas JS, Spiro CN, Haimm CA, et al. Long-term effects from a school-based trial comparing interpersonal psychotherapy-adolescent skills training to group counseling. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2019;48:S362–70.

Zhao Y, Yu F, Wu Y, Zeng G, Peng K. Positive education interventions prevent depression in Chinese adolescents. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1344.

Taghvaienia A, Zonobitabar A. Positive intervention for depression and teacher-student relationship in Iranian high school girl students with moderate/mild depression: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2020;14(1):25.

Iyer RB, Iyer BN. The impact of heartfulness-based elective on middle school students. Am J Health Behav. 2019;43(4):812–23.

Hoang-Minh D, Weiss B, Cao Minh N, Nam T, Pollack A. Vietnam as a case example of school-based mental health services in low and middle income countries: efficacy and effects of risk status. Sch Psychol Int. 2017;38(1):22–41.

Roberts CM, Kane RT, Rooney RM, Pintabona Y, Baughman N, Hassan S, et al. Efficacy of the aussie optimism program: promoting pro-social behavior and preventing suicidality in primary school students a randomised-controlled trial. Front Psychol. 2018;8:1392.

Coelho VA, Sousa V. Differential effectiveness of a middle school social and emotional learning program: does setting matter? J Youth Adolesc. 2018;47(9):1978–91.

Coelho VA, Sousa V. Comparing two low middle school social and emotional learning program formats: a multilevel effectiveness study. J Youth Adolesc. 2017;46(3):656–67.

Coelho VA, Sousa V, Figueira AP. The effectiveness of a Portuguese Elementary School social and emotional learning program. J Prim Prev. 2016;37(5):433–47.

Sánchez-Sansegundo M, Ferrer-Cascales R, Albaladejo-Blazquez N, Alarcó-Rosales R, Bowes N, Ruiz-Robledillo N. Effectiveness of the reasoning and rehabilitation v2 programme for improving personal and social skills in Spanish adolescent students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(9):3040.

Shoshani A, Slone M. Positive education for young children: effects of a positive psychology intervention for preschool children on subjective well being and learning behaviors. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1866.

Tomyn JD, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Richardson B, Colla L. A comprehensive evaluation of a universal school-based depression prevention program for adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2016;44(8):1621–33.

Schanen JG, Skenandore A, Scow B, Hagen J. Assessing the impact of a healthy relationships curriculum on native American adolescents. Soc Work. 2017;62(3):251–8.

Ohira I, Urao Y, Sato Y, Ohtani T, Shimizu E. A pilot and feasibility study of a cognitive behavioural therapy-based anxiety prevention programme for junior high school students in Japan: a quasi-experimental study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2019;13(1):40.

Schwager S, Berger U, Glaeser A, Strauss B, Wick AK. Evaluation of “Healthy Learning Together”, an easily applicable mental health promotion tool for students aged 9 to 18 years. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(3):487.

Filella G, Ros-Morente A, Oriol X, March-Llanes J. The assertive resolution of conflicts in school with a gamified emotion education program. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2353.

Allara E, Beccaria F, Molinar R, Marinaro L, Ermacora A, Coppo A, et al. A school-based program to promote well-being in preadolescents: results from a cluster quasi-experimental controlled study. J Prim Prev. 2019;40(2):151–70.

Fung J, Kim JJ, Jin J, Chen G, Bear L, Lau AS. A randomized trial evaluating school-based mindfulness intervention for ethnic minority youth: exploring mediators and moderators of intervention effects. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2019;47(1):1–19.

de Carvalho JS, Pinto AM, Maroco J. Results of a mindfulness-based social-emotional learning program on portuguese elementary students and teachers: a quasi-experimental study. Mindfulness. 2017;8(2):337–50.

Kang Y, Rahrig H, Eichel K, Niles HF, Rocha T, Lepp NE, et al. Gender differences in response to a school-based mindfulness training intervention for early adolescents. J Sch Psychol. 2018;68:163–76.

Wright KM, Roberts R, Proeve MJ. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for children (MBCT-C) for prevention of internalizing difficulties: a small randomized controlled trial with Australian Primary School Children. Mindfulness. 2019;10(11):2277–93.

Ghiroldi S, Scafuto F, Montecucco NF, Presaghi F, Iani L. Effectiveness of a school-based mindfulness intervention on children’s internalizing and externalizing problems: the Gaia Project. Mindfulness. 2020;11(11):2589–603.

Lam K, Seiden D. Effects of a brief mindfulness curriculum on self-reported executive functioning and emotion regulation in Hong Kong adolescents. Mindfulness. 2020;11(3):627–42.

Volanen SM, Lassander M, Hankonen N, Santalahti P, Hintsanen M, Simonsen N, et al. Healthy learning mind—effectiveness of a mindfulness program on mental health compared to a relaxation program and teaching as usual in schools: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2020;260:660–9.

Devcich DA, Rix G, Bernay R, Graham E. Effectiveness of a mindfulness-based program on school children’s self-reported well-being: a pilot study comparing effects with an emotional literacy program. J Appl Sch Psychol. 2017;33(4):309–30.

Sanger KL, Thierry G, Dorjee D. Effects of school-based mindfulness training on emotion processing and well-being in adolescents: evidence from event-related potentials. Dev Sci. 2018;21(5):e12646.

Lee RLT, Lane SJ, Tang ACY, Leung C, Louie LHT, Browne G, et al. Effects of an unstructured free play and mindfulness intervention on wellbeing in kindergarten students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(15):5382.

Amundsen R, Riby LM, Hamilton C, Hope M, McGann D. Mindfulness in primary school children as a route to enhanced life satisfaction, positive outlook and effective emotion regulation. BMC Psychol. 2020;8(1):71.

Johnson C, Burke C, Brinkman S, Wade T. A randomized controlled evaluation of a secondary school mindfulness program for early adolescents: Do we have the recipe right yet? Behav Res Ther. 2017;99:37–46.

Martinsen KD, Rasmussen LP, Wentzel-Larsen T, Holen S, Sund AM, Pedersen ML, et al. Change in quality of life and self-esteem in a randomized controlled CBT study for anxious and sad children: can targeting anxious and depressive symptoms improve functional domains in schoolchildren? BMC Psychol. 2021;9(1):8.

Redfern A, Jolley S, Bracegirdle K, Browning S, Plant D. Innovations in practice: CUES-Ed: an in-service evaluation of a new universal cognitive behavioural early mental health intervention programme for primary school children. Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2019;24(2):187–91.

Terry JD, Weist MD, Strait GG, Miller M. Motivational interviewing to promote the effectiveness of selective prevention: an integrated school-based approach. Prev Sci. 2020;22:799–810.

de la Torre-Luque A, Fiol-Veny A, Essau CA, Balle M, Bornas X. Effects of a transdiagnostic cognitive behaviour therapy-based programme on the natural course of anxiety symptoms in adolescence. J Affect Disord. 2020;264:474–82.

Lowe C, Wuthrich VM. Randomised controlled trial of study without stress: a cognitive behavioural therapy program to reduce stress in students in the final year of high school. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2021;52(2):205–16.

Poppelaars M, Tak YR, Lichtwarck-Aschoff A, Engels RC, Lobel A, Merry SN, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing two cognitive-behavioral programs for adolescent girls with subclinical depression: a school-based program (Op Volle Kracht) and a computerized program (SPARX). Behav Res Ther. 2016;80:33–42.

Garmy P, Clausson EK, Berg A, Steen Carlsson K, Jakobsson U. Evaluation of a school-based cognitive-behavioral depression prevention program. Scand J Public Health. 2019;47(2):182–9.

Klim-Conforti P, Zaheer R, Levitt AJ, Cheung AH, Schachar R, Schaffer A, et al. The Impact of a Harry Potter-based cognitive-behavioral therapy skills curriculum on suicidality and well-being in middle schoolers: a randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2021;286:134–41.

Waters AM, Candy SG, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Groth TA, Craske MG, Bradley BP, et al. A school-based comparison of positive search training to enhance adaptive attention regulation with a cognitive-behavioural intervention for reducing anxiety symptoms in children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2019;47(11):1821–40.

Ahlen J, Lenhard F, Ghaderi A. Long-term outcome of a cluster-randomized universal prevention trial targeting anxiety and depression in school children. Behav Ther. 2019;50(1):200–13.

McMullen JD, McMullen N. Evaluation of a teacher-led, life-skills intervention for secondary school students in Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2018;217:10–7.

Jafarigiv S, Peyman N. The effect of life skills training with health literacy strategies on self-esteem and self-efficacy in female students during puberty. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2019-0121.

Moulier V, Guinet H, Kovacevic Z, Bel-Abbass Z, Benamara Y, Zile N, et al. Effects of a life-skills-based prevention program on self-esteem and risk behaviors in adolescents: a pilot study. BMC Psychol. 2019;7(1):82.

Fernández-Martínez I, Morales A, Espada JP, Essau CA, Orgilés M. Effectiveness of the program Super Skills For Life in reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression in young Spanish children. Psicothema. 2019;31(3):298–304.

Lee M-J, Wu W-C, Chang H-C, Chen H-J, Lin W-S, Feng JY, et al. Effectiveness of a school-based life skills program on emotional regulation and depression among elementary school students: a randomized study. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;118:105464.

Heizomi H, Allahverdipour H, Jafarabadi MA, Bhalla D, Nadrian H. Effects of a mental health promotion intervention on mental health of Iranian female adolescents: a school-based study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2020;14(1):36.

Berger R, Benatov J, Cuadros R, VanNattan J, Gelkopf M. Enhancing resiliency and promoting prosocial behavior among Tanzanian primary-school students: a school-based intervention. Transcult Psychiatry. 2018;55(6):821–45.

Khanna P, Singh K. Stress management training and gratitude journaling in the classroom: an initial investigation in Indian context. Curr Psychol. 2021;40:5737–5748.

Perry Y, Werner-Seidler A, Calear A, Mackinnon A, King C, Scott J, et al. Preventing depression in final year secondary students: school-based randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(11):e369.

Streimann K, Selart A, Trummal A. Effectiveness of a universal, classroom-based preventive intervention (PAX GBG) in Estonia: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Prev Sci. 2020;21(2):234–44.

Bolling M, Niclasen J, Bentsen P, Nielsen G. Association of education outside the classroom and pupils’ psychosocial well-being: results from a school year implementation. J Sch Health. 2019;89(3):210–8.

Harvey DJ, Montgomery LN, Harvey H, Hall F, Gange AC, Watling D. Psychological benefits of a biodiversity-focussed outdoor learning program for primary school children. J Environ Psychol. 2020;67:101381.

Dray J, Bowman J, Campbell E, Freund M, Hodder R, Wolfenden L, et al. Effectiveness of a pragmatic school-based universal intervention targeting student resilience protective factors in reducing mental health problems in adolescents. J Adolesc. 2017;57:74–89.

Olowokere AE, Okanlawon FA. Improving vulnerable school children’s psychosocial health outcomes through resilience-based training and peer-support activities: a comparative prospective study. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2018;13(4):291–304.

Kozina A. School-based prevention of anxiety using the “My FRIENDS” emotional resilience program: six-month follow-up. Int J Psychol. 2020;55:70–7.

Shinde S, Weiss HA, Khandeparkar P, Pereira B, Sharma A, Gupta R, et al. A multicomponent secondary school health promotion intervention and adolescent health: an extension of the SEHER cluster randomised controlled trial in Bihar, India. PLoS Med. 2020;17(2):e1003021.

Shinde S, Weiss HA, Varghese B, Khandeparkar P, Pereira B, Sharma A, et al. Promoting school climate and health outcomes with the SEHER multi-component secondary school intervention in Bihar, India: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10163):2465–77.

Singla DR, Shinde S, Patton G, Patel V. The mediating effect of school climate on adolescent mental health: findings from a randomized controlled trial of a school-wide intervention. J Adolesc Health. 2020;69:90–9.

Kiviruusu O, Björklund K, Koskinen HL, Liski A, Lindblom J, Kuoppamäki H, et al. Short-term effects of the “Together at School” intervention program on children’s socio-emotional skills: a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychol. 2016;4(1):27.

Yockey RA, King KA, Vidourek RA. School factors and anxiety disorder among Hispanic youth: results from the 2016 US National Survey on Children’s Health. Sch Psychol Int. 2019;40(4):403–15.

Yeo SC, Tan J, Lo JC, Chee MWL, Gooley JJ. Associations of time spent on homework or studying with nocturnal sleep behavior and depression symptoms in adolescents from Singapore. Sleep Health. 2020. (2352–7226 (Electronic)).

Nair S, Ganjiwale J, Kharod N, Varma J, Nimbalkar SM. Epidemiological survey of mental health in adolescent school children of Gujarat, India. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2017;1(1):e000139.

Lonnfjord V, Hagquist C. The association of self-reported schoolwork pressure, family factors and self-efficacy with psychosomatic problems. Eur J Soc Work. 2020;24:603–16.

Lv B, Lv L. Out-of-school activities on weekdays and adolescent adjustment in China: a person-centered approach. Child Indic Res. 2021;14(2):783–98.

Hamer M, Yates T, Sherar LB, Clemes SA, Shankar A. Association of after school sedentary behaviour in adolescence with mental wellbeing in adulthood. Prev Med. 2016;87:6–10.

Al-Qahtani AM, Al-Harbi MB. Prevalence and risk factors of anxiety among female governmental secondary schools students in Al-madinah, Saudi Arabia. Indian J Pharm Educ Res. 2017;51(1):136–43.

Long E, Zucca C, Sweeting H. School climate, peer relationships, and adolescent mental health: a social ecological perspective. Youth Soc. 2020;53:1400–15.

Malak MZ, Khalifeh AH. Anxiety and depression among school students in Jordan: prevalence, risk factors, and predictors. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2018;54(2):242–50.

Evensen M. Adolescent mental health problems, behaviour penalties, and distributional variation in educational achievement. Eur Sociol Rev. 2019;35(4):474–90.

Torrano R, Ortigosa JM, Riquelme A, Mendez FJ, Lopez-Pina JA. Test anxiety in adolescent students: different responses according to the components of anxiety as a function of sociodemographic and academic variables. Front Psychol. 2020;11:3521.

Bashir MBA, Albadawy I, Cumber SN. Predictors and correlates of examination anxiety and depression among high school students taking the Sudanese national board examination in Khartoum state, Sudan: a cross-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;33:69.

Sarı SA, Bilek G, Çelik E. Test anxiety and self-esteem in senior high school students: a cross-sectional study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2018;72(2):84–8.

Cikrikci O, Erzen E, Yeniceri IA. Self-esteem and optimism as mediators in the relationship between test anxiety and life satisfaction among a school-based sample of adolescents. J Psychol Couns Sch. 2019;29(1):39–53.

Putwain DW, Pescod M. Is reducing uncertain control the key to successful test anxiety intervention for secondary school students? Findings from a randomized control trial. Sch Psychol Q. 2018;33(2):283–92.

Fergus TA, Limbers CA. Reducing test anxiety in school settings: a controlled pilot study examining a group format delivery of the attention training technique among adolescent students. Behav Ther. 2019;50(4):803–16.

Haerens L, Krijgsman C, Mouratidis A, Borghouts L, Cardon G, Aelterman N. How does knowledge about the criteria for an upcoming test relate to adolescents’ situational motivation in physical education? A self-determination theory approach. Eur Phys Educ Rev. 2019;25(4):983–1001.

Herres J, Ewing ES, Kobak R. Emotional reactivity to negative adult and peer events and the maintenance of adolescent depressive symptoms: a daily diary design. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2016;44(3):471–81.

Adewuya AO, Oladipo EO. Prevalence and associated factors for suicidal behaviours (ideation, planning, and attempt) among high school adolescents in Lagos, Nigeria. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;29(11):1503–12.

He GH, Strodl E, Chen WQ, Liu F, Hayixibayi A, Hou XY. Interpersonal conflict, school connectedness and depressive symptoms in Chinese Adolescents: moderation effect of gender and grade level. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(12):2182.

Li J, Li J, Jia R, Wang Y, Qian S, Xu Y. Mental health problems and associated school interpersonal relationships among adolescents in China: a cross-sectional study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2020;14(1):12.

Fernandez-Sogorb A, Sanmartin R, Vicent M, Gonzalvez C. Identifying profiles of anxiety in late childhood and exploring their relationship with school-based distress. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):948.

Weyns T, Colpin H, Engels MC, Doumen S, Verschueren K. The relative contribution of peer acceptance and individual and class-level teacher-child interactions to kindergartners’ behavioral development. Early Childhood Res Q. 2019;47:259–70.

Warne M, Snyder K, Gillander GK. Participation and support—associations with Swedish pupils’ positive health. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2017;76(1):1373579.

Burns EC, Martin AJ, Collie RJ. Adaptability, personal best (PB) goals setting, and gains in students’ academic outcomes: a longitudinal examination from a social cognitive perspective. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2018;53:57–72.

Oberle E. Early adolescents’ emotional well-being in the classroom: the role of personal and contextual assets. J Sch Health. 2018;88(2):101–11.

Povedano-Diaz A, Muñiz-Rivas M, Vera-Perea M. Adolescents’ life satisfaction: the role of classroom, family, self-concept and gender. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;17(1):19.

Yun JY, Chung H, Sim JA, Yun YH. Prevalence and associated factors of depression among Korean adolescents. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(10):e0223176.

Pössel P, Burton SM, Cauley B, Sawyer MG, Spence SH, Sheffield J. Associations between social support from family, friends, and teachers and depressive symptoms in adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2018;47(2):398–412.

Tong L, Reynolds K, Lee E, Liu Y. School relational climate, social identity, and student well-being: new evidence from China on student depression and stress levels. Sch Ment Health. 2019;11(3):509–21.

Barnard AD, Adelson JL, Possel P. Associations between perceived teaching behaviours and affect in upper elementary school students. Early Child Dev Care. 2017;187(11):1795–808.

Cauley B, Possel P, Black SW, Hooper LM. Teaching behavior and positive and negative affect in high school students: does students’ race matter? Sch Ment Health. 2017;9(4):334–46.

Shukla KD, Kuril S, Chand VS. Does negative teacher behavior influence student self-efficacy and mastery goal orientation? Learn Motivation. 2020;71:101653.

Kurdi V, Archambault I. Student-teacher relationships and student anxiety: moderating effects of sex and academic achievement. Can J Sch Psychol. 2018;33(3):212–26.

Mizuta A, Suzuki K, Yamagata Z, Ojima T. Teachers’ support and depression among Japanese adolescents: a multilevel analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(2):211–9.

Quin D, Hemphill SA, Heerde JA. Associations between teaching quality and secondary students’ behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement in school. Soc Psychol Educ. 2017;20(4):807–29.

Bennefield Z. School and family correlates of positive affect in a nationally representative sample of US adolescents. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2018;35(5):541–8.

Lan X, Zhang L. Shields for emotional well-being in Chinese adolescents who switch schools: the role of teacher autonomy support and grit. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2384.

Guo C, Tomson G, Keller C, Söderqvist F. Prevalence and correlates of positive mental health in Chinese adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):263.

Corder K, Werneck AO, Jong ST, Hoare E, Brown HE, Foubister C, et al. Pathways to increasing adolescent physical activity and wellbeing: a mediation analysis of intervention components designed using a participatory approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(2):390.

Phan HP, Ngu BH. Schooling experience and academic performance of Taiwanese students: the importance of psychosocial effects, positive emotions, levels of best practice, and personal well-being. Soc Psychol Educ. 2020;23(4):1073–101.

Pereyra SB, Bean RA, Ruiz JG, Velasco B. The impact of parents and teachers on externalizing behavior among latino/a adolescents via academic achievement: combining the mental health and educational perspectives. Fam J. 2020;28(3):290–9.

Wang C, Hatzigianni M, Shahaeian A, Murray E, Harrison LJ. The combined effects of teacher-child and peer relationships on children’s social-emotional adjustment. J Sch Psychol. 2016;59:1–11.

Nie Q, Teng Z, Bear GG, Guo C, Liu Y, Zhang D. Hope as mediator between teacher-student relationships and life satisfaction among Chinese adolescents: a between- and within-person effects analysis. J Happiness Stud. 2019;20(7):2367–83.

Wong MD, Dosanjh KK, Jackson NJ, Runger D, Dudovitz RN. The longitudinal relationship of school climate with adolescent social and emotional health. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):207.

Ford T, Hayes R, Byford S, Edwards V, Fletcher M, Logan S, et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the Incredible YearsA (R) Teacher Classroom Management programme in primary school children: results of the STARS cluster randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(5):828–42.

Neal SC, Norwalk KE, Haskett ME. Differential impacts of the Incredible Years-Teacher Classroom Management program based on young children’s risk profiles. Early Childhood Res Q. 2020;51:473–82.

Carter R, Leath S, Butler-Barnes ST, Bryd CM, Chavous TM, Caldwell CH, et al. Comparing associations between perceived puberty, same-race friends and same-race peers, and psychosocial outcomes among African American and Caribbean Black girls. J Black Psychol. 2017;43(8):836–62.

Attar-Schwartz S, Mishna F, Khoury-Kassabri M. The role of classmates’ social support, peer victimization and gender in externalizing and internalizing behaviors among Canadian youth. J Child Fam Stud. 2019;28(9):2335–46.

Lyell KM, Coyle S, Malecki CK, Santuzzi AM. Parent and peer social support compensation and internalizing problems in adolescence. J Sch Psychol. 2020;83:25–49.

Laetsch A. Do perceived helpfulness and competition in classroom contexts moderate or mediate the association between perceived stress and socio-emotional strengths and difficulties from early to middle adolescence? Learn Individ Differ. 2017;58:31–40.

Ng-Knight T, Shelton KH, Riglin L, Frederickson N, McManus IC, Rice F. “Best friends forever”? Friendship stability across school transition and associations with mental health and educational attainment. Br J Educ Psychol. 2019;89(4):585–99.

Delgado MY, Nair RL, Updegraff KA, Umaña-Taylor AJ. Discrimination, parent-adolescent conflict, and peer intimacy: examining risk and resilience in Mexican-origin youths’ adjustment trajectories. Child Dev. 2019;90(3):894–910.

van Harmelen AL, Gibson JL, St Clair MC, Owens M, Brodbeck J, Dunn V, et al. Friendships and family support reduce subsequent depressive symptoms in at-risk adolescents. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(5):e0153715.

Yang Y, Chen L, Zhang L, Ji L, Zhang W. Developmental changes in associations between depressive symptoms and peer relationships: a four-year follow-up of Chinese adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2020;49(9):1913–27.

Wood MA, Bukowski WM, Santo JB. Friendship security, but not friendship intimacy, moderates the stability of anxiety during preadolescence. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2017;46(6):798–809.

Copeland M, Siennick SE, Feinberg ME, Moody J, Ragan DT. Social ties cut both ways: self-harm and adolescent peer networks. J Youth Adolesc. 2019;48(8):1506–18.

Wu N, Hou Y, Chen P, You J. Peer acceptance and nonsuicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents: a longitudinal moderated mediation model. J Youth Adolesc. 2019;48(9):1806–17.

Schmidt A, Neubauer AB, Dirk J, Schmiedek F. The bright and the dark side of peer relationships: differential effects of relatedness satisfaction and frustration at school on affective well-being in children’s daily lives. Dev Psychol. 2020;56(8):1532–46.

King RB, Datu JA. Happy classes make happy students: classmates’ well-being predicts individual student well-being. J Sch Psychol. 2017;65:116–28.

Baytemir K. Experiences of school as a mediator between interpersonal competence and happiness in adolescents. Anales De Psicologia. 2019;35(2):259–68.

Dang J, Liu L, Du Y. Benefits of a highly entitative class for adolescents’ psychological well-being in school. Sch Ment Health. 2019;11(4):766–76.

Oberle E, Guhn M, Gadermann AM, Thomson K, Schonert-Reichl KA. Positive mental health and supportive school environments: a population-level longitudinal study of dispositional optimism and school relationships in early adolescence. Soc Sci Med. 2018;214:154–61.

Tetzner J, Becker M. Why are you so optimistic? Effects of sociodemographic factors, individual experiences, and peer characteristics on optimism in early adolescents. J Pers. 2019;87(3):661–75.

Chen Y, Wang L, Zhao J. Peer relationship profiles in rural Chinese adolescents: longitudinal relations with subjective well-being. J Health Psychol. 2019;26:1803–20.

Xavier A, Cunha M, Pinto-Gouveia J. Daily peer hassles and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescence: gender differences in avoidance-focused emotion regulation processes. J Child Fam Stud. 2018;27(1):59–68.

Lessard LM, Juvonen J. Friendless adolescents: do perceptions of social threat account for their internalizing difficulties and continued friendlessness? J Res Adolesc. 2018;28(2):277–83.

Pandey AR, Bista B, Dhungana RR, Aryal KK, Chalise B, Dhimal M. Factors associated with suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts among adolescent students in Nepal: Findings from Global School-based Students Health Survey. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(4):e0210383.

Troop-Gordon W, MacDonald AP, Corbitt-Hall DJ. Children’s peer beliefs, friendlessness, and friendship quality: reciprocal influences and contributions to internalizing symptoms. Dev Psychol. 2019;55(11):2428–39.

Humenny G, Grygiel P, Dolata R, Switaj P. Peer network status and depressive symptoms among early adolescents: testing the mediating effects of metaperception and loneliness. Sch Ment Health. 2021;13:250–65.

Biswas T, Scott JG, Munir K, Renzaho AMN, Rawal LB, Baxter J, et al. Global variation in the prevalence of suicidal ideation, anxiety and their correlates among adolescents: a population based study of 82 countries. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;24:100395.

Fussner LM, Luebbe AM, Mancini KJ, Becker SP. Emotion dysregulation mediates the longitudinal relation between peer rejection and depression: differential effects of gender and grade. Int J Behav Dev. 2018;42(2):155–66.

Zhang S, Baams L, van de Bongardt D, Dubas JS. Intra- and inter-individual differences in adolescent depressive mood: the role of relationships with parents and friends. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2018;46(4):811–24.

Mali LV, Schwartz D, Badaly D, Luo TJ, Malamut S, Ross AC, et al. Unpopularity with same- and cross-ethnicity peers as predictors of depressive symptoms during adolescence. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2019;62:93–101.

Martinez G, Bámaca-Colbert MY. A reciprocal and longitudinal investigation of peer and school stressors and depressive symptoms among mexican-origin adolescent females. J Youth Adolesc. 2019;48(11):2125–40.

Benas JS, McCarthy AE, Haimm CA, Huang M, Gallop R, Young JF. The depression prevention initiative: impact on adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms in a randomized trial. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2019;48(sup1):S57-s71.

Van Ryzin MJ, Roseth CJ. The cascading effects of reducing student stress: cooperative learning as a means to reduce emotional problems and promote academic engagement. J Early Adolesc. 2020;41:700–24.

Farren GL, Zhang T, Gu X, Thomas KT. Sedentary behavior and physical activity predicting depressive symptoms in adolescents beyond attributes of health-related physical fitness. J Sport Health Sci. 2018;7(4):489–96.

Bell SL, Audrey S, Gunnell D, Cooper A, Campbell R. The relationship between physical activity, mental wellbeing and symptoms of mental health disorder in adolescents: a cohort study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019;16(1):138.

Opdal IM, Morseth B, Handegård BH, Lillevoll K, Ask H, Nielsen CS, et al. Change in physical activity is not associated with change in mental distress among adolescents: the Tromsø study: fit futures. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):916.

Belton S, Issartel J, McGrane B, Powell D, O’Brien W. A consideration for physical literacy in Irish youth, and implications for physical education in a changing landscape. Ir Educ Stud. 2019;38(2):193–211.

Barth Vedøy I, Anderssen SA, Tjomsland HE, Skulberg KR, Thurston M. Physical activity, mental health and academic achievement: a cross-sectional study of Norwegian adolescents. Ment Health Phys Act. 2020;18:100322.

Wunsch K, Nigg CR, Weyland S, Jekauc D, Niessner C, Burchartz A, et al. The relationship of self-reported and device-based measures of physical activity and health-related quality of life in adolescents. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19(1):67.

Park S, Park SY, Jang SY, Oh G, Oh IH. The neglected role of physical education participation on suicidal ideation and stress in high school adolescents from South Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2838.

Rizal H, Hajar MS, Muhamad AS, Kueh YC, Kuan G. The effect of brain breaks on physical activity behaviour among primary school children: a transtheoretical perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(21):4283.

Cornelius C, Fedewa A, Toland M. A classroom-based physical activity intervention for adolescents: is there an effect on self-efficacy, physical activity, and on-task behavior? Health Psychol Rep. 2020;8(4):408–27.

Mok MMC, Chin M-K, Korcz A, Popeska B, Edginton CR, Uzunoz FS, et al. Brain breaks (R) physical activity solutions in the classroom and on attitudes toward physical activity: a randomized controlled trial among primary students from eight countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(5):1666.

Sherry AP, Pearson N, Ridgers ND, Johnson W, Barber SE, Bingham DD, et al. Impacts of a standing desk intervention within an english primary school classroom: a pilot controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(19):7048.

Avitsland A, Leibinger E, Resaland GK, Solberg RB, Kolle E, Dyrstad SM. Effects of school-based physical activity interventions on mental health in adolescents: the School in Motion cluster randomized controlled trial. Ment Health Phys Act. 2020;19:100348.

Schmidt SK, Reinboth MS, Resaland GK, Bratland-Sanda S. Changes in physical activity, physical fitness and well-being following a school-based health promotion program in a Norwegian region with a poor public health profile: a non-randomized controlled study in early adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(3):896.

Costigan SA, Eather N, Plotnikoff RC, Hillman CH, Lubans DR. High-intensity interval training for cognitive and mental health in adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(10):1985–93.

Ruiz-Ariza A, Suarez-Manzano S, Lopez-Serrano S, Martinez-Lopez EJ. The effect of cooperative high-intensity interval training on creativity and emotional intelligence in secondary school: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Phys Educ Rev. 2019;25(2):355–73.

Cocca A, Espino Verdugo F, Ródenas Cuenca LT, Cocca M. Effect of a game-based physical education program on physical fitness and mental health in elementary school children. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(13):4883.

Andrade A, Cruz WMD, Correia CK, Santos ALG, Bevilacqua GG. Effect of practice exergames on the mood states and self-esteem of elementary school boys and girls during physical education classes: a cluster-randomized controlled natural experiment. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(6):e0232392.

Zhang Y, Yin Y, Liu J, Yang M, Liu Z, Ma X. Impact of combined theory-based intervention on psychological effects and physical activity among chinese adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(9):3026.

Koszałka-Silska A, Korcz A, Wiza A. The impact of physical education based on the adventure education programme on self-esteem and social competences of adolescent boys. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(6):1–14.

Resaland GK, Aadland E, Moe VF, Kolotkin RL, Anderssen SA, Andersen JR. Effects of a physical activity intervention on schoolchildren’s health-related quality of life: the active smarter kids (ASK) cluster-randomized controlled trial. Prev Med Rep. 2019;13:1–4.

Smith JJ, Beauchamp MR, Faulkner G, Morgan PJ, Kennedy SG, Lubans DR. Intervention effects and mediators of well-being in a school-based physical activity program for adolescents: the “Resistance Training for Teens” cluster RCT. Ment Health Phys Act. 2018;15:88–94.

Luna P, Guerrero J, Cejudo J. Improving adolescents’ subjective well-being, trait emotional intelligence and social anxiety through a programme based on the sport education model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(10):1821.

Gall S, Walter C, du Randt R, Adams L, Joubert N, Mueller I, et al. Changes in self-reported physical activity predict health-related quality of life among south african schoolchildren: findings from the DASH Intervention Trial. Front Public Health. 2020;8:580.

Halliwell E, Jarman H, Tylka TL, Slater A. Evaluating the impact of a brief yoga intervention on preadolescents’ body image and mood. Body Image. 2018;27:196–201.

Shreve M, Scott A, McNeill C, Washburn L. Using yoga to reduce anxiety in children: exploring school-based yoga among rural third- and fourth-grade students. J Pediatr Health Care. 2021;35(1):42–52.

Hyakutake A, Kamijo T, Misawa Y, Washizuka S, Inaba Y, Tsukahara T, et al. Cross-sectional observation of the relationship of depressive symptoms with lifestyles and parents’ status among Japanese junior high school students. Environ Health Prev Med. 2016;21(4):265–73.

McMahon EM, Corcoran P, O’Regan G, Keeley H, Cannon M, Carli V, et al. Physical activity in European adolescents and associations with anxiety, depression and well-being. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;26(1):111–22.

Tajik E, Abd Latiff L, Adznam SN, Awang H, Yit Siew C, Abu Bakar AS. A study on level of physical activity, depression, anxiety and stress symptoms among adolescents. J Sports Med Phys Fit. 2017;57(10):1382–7.

Kleppang AL, Thurston M, Hartz I, Hagquist C. Psychological distress among Norwegian adolescents: changes between 2001 and 2009 and associations with leisure time physical activity and screen-based sedentary behaviour. Scand J Public Health. 2019;47(2):166–73.

Bélair MA, Kohen DE, Kingsbury M, Colman I. Relationship between leisure time physical activity, sedentary behaviour and symptoms of depression and anxiety: evidence from a population-based sample of Canadian adolescents. BMJ Open. 2018;8(10):e021119.

O’Brien K, Agostino J, Ciszek K, Douglas KA. Physical activity and risk of behavioural and mental health disorders in kindergarten children: analysis of a series of cross-sectional complete enumeration (census) surveys. BMJ Open. 2020;10(3):e034847.

Guddal MH, Stensland S, Småstuen MC, Johnsen MB, Zwart JA, Storheim K. Physical activity and sport participation among adolescents: associations with mental health in different age groups. Results from the Young-HUNT study: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):e028555.

Reverdito RS, Carvalho HM, Galatti LR, Scaglia AJ, Gonçalves CE, Paes RR. Effects of youth participation in extra-curricular sport programs on perceived self-efficacy: a multilevel analysis. Percept Mot Skills. 2017;124(3):569–83.

Oosterhoff B, Kaplow JB, Wray-Lake L, Gallagher K. Activity-specific pathways among duration of organized activity involvement, social support, and adolescent well-being: findings from a nationally representative sample. J Adolesc. 2017;60:83–93.

Jiang R, Xie C, Shi J, Mao X, Huang Q, Meng F, et al. Comparison of physical fitness and mental health status among school-age children with different sport-specific training frequencies. PeerJ. 2021;9:e10842.

Tu HM. Does active leisure participation promote psychological capital through peer support in economically disadvantaged children? PLoS ONE. 2020;15(6):e0234143.

Moeijes J, van Busschbach JT, Bosscher RJ, Twisk JWR. Sports participation and psychosocial health: a longitudinal observational study in children. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):702.

Kleppang AL, Hartz I, Thurston M, Hagquist C. The association between physical activity and symptoms of depression in different contexts—a cross-sectional study of Norwegian adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1368.

Guzmán-Rocha MD, McLeod DL, Bohnert AM. Dimensions of organized activity involvement among Latino youth: impact on well-being. J Adolesc. 2017;60:130–9.

Oberle E, Ji XR, Kerai S, Guhn M, Schonert-Reichl KA, Gadermann AM. Screen time and extracurricular activities as risk and protective factors for mental health in adolescence: a population-level study. Prev Med. 2020;141:106291.