Abstract

Background

Human papillomavirus (HPV) prevalence in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) diverges geographically. The reliability of using p16INK4a expression as a marker of viral infection is controversial in HNSCC. We evaluated HPV types and HPV-16 variants prevalence, and p16INK4a expression in HNSCC specimens provided by two different Institutions in São Paulo.

Methods

HPV DNA from formalin-fixed specimens was accessed by Inno-LiPA, HPV-16 variants by PCR-sequencing, and p16INK4a protein levels by immunohistochemistry.

Results

Overall, HPV DNA was detected among 19.4 % of the specimens (36/186). Viral prevalence was higher in the oral cavity (25.0 %, 23/92) then in other anatomical sites (oropharynx 14,3 %, larynx 13.7 %) when samples from both Institutions were analyzed together. HPV prevalence was also higher in the oral cavity when samples from both Institutions were analyzed separately. HPV-16 was the most prevalent type identified in 69.5 % of the HPV positive smaples and specimens were assigned into Asian-American (57.2 %) or European (42.8 %) phylogenetic branches. High expression of p16INK4a was more common among HPV positive tumors.

Conclusion

Our results support a role for HPV-16 in a subset of HNSCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Worldwide head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the sixth most common type of cancer with an estimated annual incidence of approximately 600,000 cases [1]. HNSCC comprises squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) of the oral cavity, oropharynx, larynx and hypopharynx. In Brazil, head and neck cancer is the fourth and seventh most incident tumor among man and women, respectively [2].

Although alcohol and tobacco consumption is the leading predisposing risk factor for HNSCC development [3], there are epidemiological evidences that human papillomavirus (HPV) infection further plays an etiological role. In fact, since 2009, the International Agency for Research on Cancer recognizes HPV-16 as an independent causal agent of oropharyngeal SCC, while the carcinogenic effect upon the oral cavity and the larynx is still a matter of debate [4]. HPV prevalence in HNSCC ranges from 10 % to 90 % dependent of the geographical region and the anatomical site of the tumor [5]. HPV-related and unrelated HNSCC diverge considerably at the genetic, molecular, epidemiological, and clinical level [6]. HPV-positive HNSCC are more common among young adults and non-smokers, and these individuals respond better to treatment and have better survival than their HPV-negative counterparts [7].

HPV-16 intratype nucleotide heterogeneity has been extensively studied [8]. Based on differences in identity of less than 2 % within the L1 gene, HPV-16 molecular variants are clustered in five branches of phylogenetic and geographical relatedness: European (E), Asian-American (AA), Asian (As), African-1 (Af-1) and African-2 (Af-2) [9, 10]. The association of HPV-16 non-European variants with increased risk of developing cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) was observed in several studies in Brazil and the United States [11–13].

The detection of HPV DNA in HNSCC is not a sufficient proof for causal viral association. High-risk HPV E7 inactivates the retinoblastoma protein, thus promoting p16INK4 overexpression. In the cervix, p16INK4a upregulation is being used as an indirect measure of oncogenically active HPV infection [14]. Although HPV DNA detection associated to high levels of p16INK4a has also been used as surrogate marker of biologically relevant viral infections in the oropharynx [15], for other head and neck subsites data is still inconsistent. It is crucial to precisely identify HPV-driven HNSCC in each population in order to improve clinical management of this disease, and to evaluate the potential benefits of the prophylactic vaccines available. Our aim was to analyze the prevalence of HPV types and HPV-16 variants in HNSCC from different anatomical sites of individuals treated at two Institutions in the city of São Paulo, and further evaluate p16INK4a protein levels in these samples.

Methods

Clinical samples

Inclusion criteria consisted of histological confirmation of HNSCC, information about the year of diagnosis and no treatment prior to surgical procedure. Formalin-fixed Paraffin Embedded (FFPE) tumor specimens from 96 HNSCC patients diagnosed between 1991 and 2010 were retrieved from the pathology archives of the Santa Casa de Sao Paulo, School of Medicine (FCMSCSP). Further, 109 FFPE HNSCC specimens from patients treated at the Cancer Institute of São Paulo (ICESP) from 2009 to 2012 were included in this study. Samples were selected from the pathology services of both institutions following a chronological sequence, availability and quality of specimen (for molecular analyses). All sections were reviewed by a pathologist of each participant Institution. Based on anatomical subsite localization of the tumor, specimens were categorized as oral cavity (oral tongue, gum, mouth, floor of mouth, lips), oropharynx (base of tongue, tonsil, oropharynx), and larynx, according to The International Classification of Diseases criteria of the World Health Organization. The ethics committees of both institutions approved all study procedures.

DNA Extraction and HPV detection

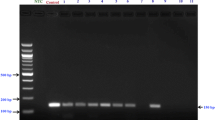

About ten 6 μm paraffin sections were obtained; the first and last sections were submitted to histological analysis, while the remaining was submitted to DNA isolation. After removing paraffin with xylene, tissues were digested with proteinase K 1 mg/mL-SDS 0.1 % for 24 h. DNA was obtained by organic extraction: after addition of Phenol/Chloroform/Isoamyl Alcohol at 25:24:1 followed by vigorous homogenization and centrifugation, DNA precipation was conducted with ethanol 100 %. The DNA pellet was dried and was dissolved in 100 μL of TE. DNA concentration was determined with a Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA). Samples were diluted to 50 ng/uL and 2 μl were used in each PCR. DNA quality was assessed by amplification of a 110 bp fragment of the human β-globin gene using PCO3/PCO4 primers followed by analysis in 8 % acrylamide gel electrophoresis [16]. The Inno-LiPA HPV Genotyping kit (Innogenetics, Gent, Belgium) was used for HPV DNA detection and genotyping as described [17]. This kit identifies 28 different HPV types by reverse blot hybridization: 6, 11, 16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 40, 43, 44, 45, 51, 52, 53, 54, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 69, 70, 71, 73, 74, 82.

HPV-16 variant characterization

A 193 bp segment of the LCR (nt 7744–33) (Forward CTAACCTAATTGCATATTTGG; Reverse ACGCCCTTAGTTTTATACATG) and/or a 108 bp fragment of the E6 gene (nt 266–374) (Forward AGAGATGGGAATCCATATGC; Reverse: GCTGTTCTAATGTTGTTCCATAC) were amplified using AmpliTaq Gold polymerase (Perkin-Elmer, CA, USA). PCR products were cloned with TOPO TA Cloning® kit for Sequencing (Invitrogen, CA, USA). Sequencing was conducted in a PRISM® 3100 Genetic Analyser (AB Applied Biosystems, CA, USA) using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing kit (AB Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). Sequences alignment was achieved using Bioedit 7.2.5, and HPV-16 variants were defined as previously described [8, 10].

P16INK4a expression

Immunohistochemistry for p16 INK4a was performed using the CINtec® P16INK4a Histology Detection kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) in a Ventana Benchmark GX equipment (Ventana Medical Systems, Arizona, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Staining of the samples from both institutions (FCMSCSP and ICESP) were analyzed by the same pathologist at ICESP (S.F.F). Expression of p16INK4a was scored as high (≥75 % of cells stained), low (<75 % of cells stained) or negative (no staining). Diverse studies use this scoring system for defining p16INK4a as positive in oropharyngeal SCC staining [18].

Statistical analysis

Qualitative data were expressed as absolute numbers and relative rates with 95 % confidence interval (95 % CI), and quantitative data as means, medians and range. The Chi-square test was used to compare phenomena between qualitative variables. For all analysis the probability of a making an α or type I error was equal to or less than 5 % (P ≤ 0.05) and SPSS® version 17.0 (SPSS® Inc; Illinois, USA) was used.

Results

All samples that were negative for human β-globin gene amplification were excluded from the study (n = 17); remaining 94 patients from each institution (FCMSCSP and ICESP). The median age of patients from FCMSCSP was 58 years, ranging from 39 to 87 years, and most individuals were male (86 %). Among specimens from ICESP, median age was 61.5 years with a range of 43 to 91 years (Table 1).

Concerning samples obtained from FCMSCSP, most tumors were from the larynx (n = 59, 62.8 %), followed by the oral cavity (n = 22, 23.4 %) and the oropharynx (n = 11, 11.7 %). For two samples (2.1 %) the anatomic site could not be defined due to the extension of the tumor, and both specimens were also excluded from analysis. Most cases from ICESP were derived from the oral cavity (n = 70, 74.5 %), followed by the oropharynx (n = 17, 18.0 %) and the larynx (n = 7, 7.5 %).

The presence of HPV DNA was investigated in all 186 cases of HNSCC (92 from FCMSCSP and 94 from ICESP). When the two cohorts were analyzed together, overall HPV DNA prevalence was 19.4 % (36/186); HPV prevalence was higher in the oral cavity (25.0 %, 23/92), and similar viral DNA rates were observed in the oropharynx (14.3 %, 4/28) and the larynx (13.7 %, 9/66). HPV prevalence was also the highest in the oral cavity when samples from both institutions were analyzed separately: 18.2 % and 27.2 % of the samples from FCMSCSP and ICESP were PCR positive, respectively (Fig. 1). While among samples from FCMSCSP viral prevalence was higher in larynx as compared to the oropharynx, the opposite was observed in ICESP specimens. Nevertheless, none of the differences observed are statistically significant (P > 0.05). For both series of cases, HPV-16 was the most commonly detected viral type, identified in 69.5 % (25/36) of the HPV positive specimens (Table 2). Co-infections by HPV-16 and HPV-18 were detected in two oral cavity samples from ICESP.

We initially thought to characterize HPV-16 molecular variants based in the nucleotide sequence pattern of a fragment of the E6 gene. However, we were unable to amplify this viral segment in six samples. For this reason, we further performed a PCR using primers able to amplify a segment of the HPV-16 LCR. Even though, we had no success in the amplification of four specimens. Overall, we detected European and Asian-American HPV-16 variants in 12 (57.2 %) and 9 (42.8 %) of the specimens, respectively (Table 3).

It was possible to evaluate p16INK4a expression by immunohistochemistry in 94 and 87 specimens from FCMSCSP and ICESP, respectively. Table 4 shows the association of HPV positivity and p16INK4a expression in the different HNSCC tumor sites of samples obtained from both institutions. We observed that independently of the anatomical site of the tumor, p16INK4a high expression (>75 % of cells stained) was more common among HPV positive specimens.

Discussion

Since the early 1980s morphological and immunohistochemical evidence points towards the involvement of HPV in oral SCC [19]. Furthermore, risk factors for HNSCC are remarkably comparable to those of cervical cancer, comprising multiple sexual partners, younger age at first sexual intercourse and oral sex practice [20, 21]. Actually, over the last decade it became clear that HPV-16 is etiologically linked to a defined subset of HNSCC, mainly in the oropharynx, and more specifically in the tonsils [22]. An etiologic link between HPV and non-oropharyngeal tumors is less firmly established [23, 24].

Reported detection rates of HPV DNA in HNSCC worldwide vary considerably, ranging from 0 % to 100 % in the oropharynx [25]. Nevertheless, HPV is recognized by now as the major cause of oropharyngeal cancer in developed countries, and HPV-16 detection is associated to the rapid rise in the incidence of this neoplasia over the last decade particularly in the USA, Sweden, and Australia, where it causes more than 50 % of cases [26, 27]. Among the HNSCC samples analyzed in our study, overall HPV prevalence was 19.4 %, being highest in the oral cavity as compared to the other anatomical sites. Our results are consistent with another studies conducted in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro in which HPV prevalence observed was 19.2 % (22/114) and 15.5 % (11/71) in oral SCC, respectively [28, 29], but is otherwise much higher than described in another study involving 132 oral tumor samples from four countries in Latin America including Brazil (HPV prevalence was 0.0 %) [30]. When restricting the comparison solely to laryngeal SCC, we detected HPV DNA in ~14.0 % of the samples from both institutions, similar to previously reported in a study that gathered samples from 4 Brazilian cities [31]. We have also found higher HPV DNA prevalence in oropharyngeal cancers as previously reported on tumors from Brazil [30, 31]. Interestingly, we found differences in oropharyngeal HPV prevalence between the two groups of samples analyzed by us (9.0 % in FCMSCSP and 17.7 % in ICESP). Nevertheless, for all anatomical sites our study has detected lower HPV DNA prevalence when compared to studies conducted in the USA and Europe [5, 26, 32]. Divergence in HPV DNA rates observed could be attributed not only to differences in the methodologies used for HPV detection in the different studies, but also to the characteristics of the individuals under study, including sexual practices, economic and social status. Unfortunately, the lack of sociodemographic and sexual behavior information of the individuals evaluated by us hampers any additional analysis.

Consistent with all studies conducted worldwide HPV-16 was the most prevalent viral type detected independently of the HNSCC anatomical subsite, and was identified in 69.5 % (25/36) of the HPV positive tumors. We and others have reported that in the uterine cervix non-European variants are linked to a higher oncogenic potential [33, 34], and to increased risk of invasive cancer as compared to European isolates [11, 12]. Concerning HPV-16 intratypic analysis in HNSCC, there is still limited data available. Gillison [22] examined HPV-16 sequence variability in 52 HNSCC in the USA and detected a predominance of European variants (75 %), while Asiatic (17 %), North-American (4 %) and African (4 %) variants were less represented. Furthermore, as previously reported for the uterine cervix, in studies conducted in Europe, >90 % of the HPV-16 variants detected in HNSCC belongs to the European branch [35, 36], with the exception of a study from Italy in which about 20 % of the HPV-16 positive cases consisted of African variants [37]. To our knowledge this is the first report concerning description of HPV-16 variability in head and neck tumor specimens in Brazil. Among the HNSCC samples that we were able to characterize the HPV-16 variant, we observe overall slight predominance of European variants followed by Asian-American isolates, comparable to our report on normal cervical samples [11]. In this way it seems that variant distribution reported in HNSCC merely reflects the overall frequency of circulating variants in the populations studied and correlates with the intrinsic admixture level of each population similar to previously reported for the cervical region [38]. It is noteworthy, that all HPV-16 oropharyngeal SCC samples analyzed by us comprise Asian-American variants. Still, the very limited number of samples analyzed precludes further conclusions. Accordingly, natural history studies of HPV in head and neck subsites are crucial to better evaluate the clinical relevance of HPV-16 heterogeneity on viral infection persistence and HNSCC development, predominantly in oropharyngeal SCC where it plays a casual role.

Only the detection of HPV DNA in HNSCC biopsies is not enough evidence of tumor causation and other parameters should be analyzed to prove the pathogenic role of viral infection. Even though overexpression of p16INK4a may also derive from non-viral alterations [39], it has been proven efficient as a surrogate marker of HPV activity in cervical samples [40]. The use of this marker to clinically detect an oncogenically active HPV infection in oropharyngeal SCC has also been described [41]; however, in oral SCC, this correlation is still controversial [42]. We observed that p16INK4a high expression (>75 % cells stained) was more commonly observed in HPV positive tumors, especially among oropharyngeal samples for which 75 % of HPV positive samples overexpressed this protein.

Conclusions

In summary, we observe that in our population overall HPV prevalence is lower than reported in developed countries, even though HPV-16 was the most prevalent viral type as observed in all studies conducted worldwide. HPV-16 variant distribution detected in our samples seemed to replicate data of the uterine cervix in our population. However, the role of HPV-16 intratypic variability in HNSCC development deserves further analysis. Nevertheless, the fact that HPV16 accounted for almost all HPV positive HNSCC samples indicates that developed prophylactic vaccines for cervical cancer could also be relevant for HNSCC prevention in our population.

Abbreviations

- AA:

-

Asian-American

- Af-1:

-

African-1

- Af-2:

-

African-2

- As:

-

Asian

- CIN:

-

cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

- E:

-

European

- FCMSCSP:

-

Santa Casa de Sao Paulo School of Medicine

- FFPE:

-

formalin-fixed paraffin embedded

- HNSCC:

-

head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- HPV:

-

human papillomavirus

- ICESP:

-

cancer institute of São Paulo

- SCC:

-

squamous cell carcinomas

References

Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–917.

INCA (Instituto Nacional do Câncer). http://www2.inca.gov.br/wps/wcm/connect/inca/portal/home. Accessed 27 March 2015.

Castellsagué X, Quintana MJ, Martínez MC, Nieto A, Sánchez MJ, Juan A, Monner A, Carrera M, Agudo A, Quer M, Muñoz N, Herrero R, Franceschi S, Bosch FX. The role of type of tobacco and type of alcoholic beverage in oral carcinogenesis. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:741–9.

Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Freeman C, Galichet L, Cogliano V. WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group. A review of human carcinogens-Part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:321–2.

Kreimer AR, Clifford GM, Boyle P, Franceschi S. Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:467–75.

Gillison ML, Broutian T, Pickard RK, Tong ZY, Xiao W, Kahle L, Graubard BI, Chaturvedi AK. Prevalence of oral HPV infection in the United States, 2009–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:693–703.

Salazar CR, Anayannis N, Smith RV, Wang Y, Haigentz Jr M, Garg M, Schiff BA, Kawachi N, Elman J, Belbin TJ, Prystowsky MB, Burk RD, Schlecht NF. Combined P16 and human papillomavirus testing predicts head and neck cancer survival. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:2404–12.

Smith B, Chen Z, Reimers L, Van Doorslaer K, Schiffman M, Desalle R, Herrero R, Yu K, Wacholder S, Wang T. Burk RD Sequence imputation of HPV16 genomes for genetic association studies. PLoS One. 2011;6, e21375.

Chen Z, Terai M, Fu L, Herrero R, DeSalle R, Burk RD. Diversifying selection in human papillomavirus type 16 lineages based on complete genome analyses. J Virol. 2005;79:7014–23.

Ho L, Chan SY, Burk RD, Das BC, Fujinaga K, Icenogle JP, Kahn T, Kiviat N, Lancaster W, Mavromara-Nazos P, et al. The genetic drift of human papillomavirus type 16 is a means of reconstructing prehistoric viral spread and the movement of ancient human populations. J Virol. 1993;67:6413–23.

Sichero L, Ferreira S, Trottier H, Duarte-Franco E, Ferenczy A, Franco EL, Villa LL. High grade cervical lesions are caused preferentially by non-European variants of HPVs 16 and 18. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:1763–8.

Xi LF, Koutsky LA, Galloway DA, Kuypers J, Hughes JP, Wheeler CM, Holmes KK, Kiviat NB. Genomic variation of human papillomavirus type 16 and risk for high grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:796–802.

Zuna RE, Moore WE, Shanesmith RP, Dunn ST, Wang SS, Schiffman M, Blakey GL, Teel T. Association of HPV16 E6 variants with diagnostic severity in cervical cytology samples of 354 women in a US population. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:2609–13.

von Knebel DM, Reuschenbach M, Schmidt D, Bergeron C. Biomarkers for cervical cancer screening: the role of p16(INK4a) to highlight transforming HPV infections. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2012;9:149–63.

Langendijk JA, Psyrri A. The prognostic significance of P16INK4A overexpression in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: implications for treatment strategies and future clinical studies. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1931–4.

Saiki RK, Gelfand DH, Stoffel S, Scharf SJ, Higuchi R, Horn GT, Mullis KB, Erlich HA. Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science. 1988;239:487–91.

Kleter B, Van Doorn LJ, Schrauwen L, Molijn A, Sastrowijoto S, Ter Schegget J, Lindeman J, Ter Harmsel B, Burger M, Quint W. Development and clinical evaluation of a highly sensitive PCR-reverse hybridization line probe assay for detection and identification of anogenital human papillomavirus. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2508–17.

Rischin D, Young RJ, Fisher R, Fox SB, Le QT, Peters LJ, Solomon B, Choi J, O'Sullivan B, Kenny LM, McArthur GA. Prognostic significance of p16INK4A and human papillomavirus in patients with oropharyngeal cancer treated on TROG 02.02 phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4142–8.

Syrjänen K, Syrjänen S, Lamberg M, Pyrhönen S, Nuutinen J. Morphological and immunohistochemical evidence suggesting human papillomavirus (HPV) involvement in oral squamous cell carcinogenesis. Int J Oral Surg. 1983;12:418–24.

Gillison ML, D'Souza G, Westra W, Sugar E, Xiao W, Begum S. Viscidi R Distinct risk factor profiles for human papillomavirus type 16-positive and human papillomavirus type 16-negative head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:407–20.

Heck JE, Berthiller J, Vaccarella S, Winn DM, Smith EM, Shan'gina O, Schwartz SM, Purdue MP, Pilarska A, Eluf-Neto J, Menezes A, McClean MD, Matos E, Koifman S, Kelsey KT, Herrero R, Hayes RB, Franceschi S, Wünsch-Filho V, Fernández L, Daudt AW, Curado MP, Chen C, Castellsagué X, Ferro G, Brennan P, Boffetta P, Hashibe M. Sexual behaviours and the risk of head and neck cancers: a pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology (INHANCE) consortium. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:166–81.

Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, Spafford M, Westra WH, Wu L, Zahurak ML, Daniel RW, Viglione M, Symer DE, Shah KV, Sidransky D. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:709–20.

Isayeva T, Li Y, Maswahu D, Brandwein-Gensler M. Human papillomavirus in non-oropharyngeal head and neck cancers: a systematic literature review. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6 Suppl 1:S104–20.

Syrjänen S, Lodi G, von Bültzingslöwen I, Aliko A, Arduino P, Campisi G, Challacombe S, Ficarra G, Flaitz C, Zhou HM, Maeda H, Miller C, Jontell M. Human papillomaviruses in oral carcinoma and oral potentially malignant disorders: a systematic review. Oral Dis. 2011;17 Suppl 1:58–72.

Tornesello ML, Perri F, Buonaguro L, Ionna F, Buonaguro FM, Caponigro F. HPV-related oropharyngeal cancers: from pathogenesis to new therapeutic approaches. Cancer Lett. 2014;351:198–205.

Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Hernandez BY, Xiao W, Kim E, Jiang B, Goodman MT, Sibug-Saber M, Cozen W, Liu L, Lynch CF, Wentzensen N, Jordan RC, Altekruse S, Anderson WF, Rosenberg PS, Gillison ML. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4294–301.

Näsman A, Attner P, Hammarstedt L, Du J, Eriksson M, Giraud G, Ahrlund-Richter S, Marklund L, Romanitan M, Lindquist D, Ramqvist T, Lindholm J, Sparén P, Ye W, Dahlstrand H, Munck-Wikland E, Dalianis T. Incidence of human papillomavirus (HPV) positive tonsillar carcinoma in Stockholm, Sweden: an epidemic of viral-induced carcinoma? Int J Cancer. 2009;125:362–6.

Hauck F, Oliveira-Silva M, Dreyer JH, Perrusi VJ, Arcuri RA, Hassan R, Bonvicino CR, Barros MH, Niedobitek G. Prevalence of HPV infection in head and neck carcinomas shows geographical variability: a comparative study from Brazil and Germany. Virchows Arch. 2015;466:685–93.

Kaminagakura E, Villa LL, Andreoli MA, Sobrinho JS, Vartanian JG, Soares FA, Nishimoto IN, Rocha R, Kowalski LP. High-risk human papillomavirus in oral squamous cell carcinoma of young patients. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:1726–32.

Ribeiro KB, Levi JE, Pawlita M, Koifman S, Matos E, Eluf-Neto J, Wunsch-Filho V, Curado MP, Shangina O, Zaridze D, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, Lissowska J, Daudt A, Menezes A, Bencko V, Mates D, Fernandez L, Fabianova E, Gheit T, Tommasino M, Boffetta P, Brennan P, Waterboer T. Low human papillomavirus prevalence in head and neck cancer: results from two large case–control studies in high-incidence regions. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:489–502.

López RV, Levi JE, Eluf-Neto J, Koifman RJ, Koifman S, Curado MP, Michaluart-Junior P, Figueiredo DL, Saggioro FP, de Carvalho MB, Kowalski LP, Abrahão M, de Góis-Filho F, Tajara EH, Waterboer T, Boffetta P, Brennan P, Wünsch-Filho V. Human papillomavirus (HPV) 16 and the prognosis of head and neck cancer in a geographical region with a low prevalence of HPV infection. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:461–71.

D'Souza G, Kreimer AR, Viscidi R, Pawlita M, Fakhry C, Koch WM, Westra WH, Gillison ML. Case–control study of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1944–56.

Lichtig H, Algrisi M, Botzer LE, Abadi T, Verbitzky Y, Jackman A, Tommasino M, Zehbe I, Sherman L. HPV16 E6 natural variants exhibit different activities in functional assays relevant to the carcinogenic potential of E6. Virology. 2006;350:216–27.

Sichero L, Sobrinho JS, Villa LL. Oncogenic potential diverge among human papillomavirus type 16 natural variants. Virology. 2012;432:127–32.

Boscolo-Rizzo P, Da Mosto MC, Fuson R, Frayle-Salamanca H, Trevisan R, Del Mistro A. HPV-16 E6 L83V variant in squamous cell carcinomas of the upper aerodigestive tract. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135:559–66.

Du J, Nordfors C, Näsman A, Sobkowiak M, Romanitan M, Dalianis T, Ramqvist T. Human papillomavirus (HPV) 16 E6 variants in tonsillar cancer in comparison to those in cervical cancer in Stockholm, Sweden. PLoS One. 2012;7, e36239.

Barbieri D, Nebiaj A, Strammiello R, Agosti R, Sciascia S, Gallinella G, Landini MP, Caliceti U, Venturoli S. Detection of HPV16 African variants and quantitative analysis of viral DNA methylation in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas. J Clin Virol. 2014;60:243–9.

Yamada T, Manos MM, Peto J, Greer CE, Munoz N, Bosch FX, Wheeler CM. Human papillomavirus type 16 sequence variation in cervical cancers: a worldwide perspective. J Virol. 1997;71:2463–72.

Klingenberg B, Hafkamp HC, Haesevoets A, Manni JJ, Slootweg PJ, Weissenborn SJ, Klussmann JP, Speel EJ. p16 INK4A overexpression is frequently detected in tumour-free tonsil tissue without association with HPV. Histopathology. 2010;56:957–67.

Klaes R, Friedrich T, Spitkovsky D, Ridder R, Rudy W, Petry U, Dallenbach-Hellweg G, Schmidt D, von Knebel Doeberitz M. Overexpression of P16INK4A (INK4A) as a specific marker for dysplastic and neoplastic epithelial cells of the cervix uteri. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:276–84.

Braakhuis BJ, Snijders PJ, Keune WJ, Meijer CJ, Ruijter-Schippers HJ, Leemans CR, Brakenhoff RH. Genetic patterns in head and neck cancers that contain or lack transcriptionally active human papillomavirus. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:998–1006.

Smith EM, Wang D, Kim Y, Rubenstein LM, Lee JH, Haugen TH, Turek LP. P16INK4a expression, human papillomavirus, and survival in head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2008;44:133–42.

Acknowledgements

ᅟ

Fundings

Supported by grants from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) [Grants numbers 11/09616-9 and 08/57889-1 to LLV; 12/01513-9 to JCB], Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tencnológico (CNPq) [Grant number 573799/2008-3 to LLV]. Additional support was provided by the São Paulo branch of the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research. We are grateful to Natália Cruz for sample collection and to Maria Cecília Costa for help in DNA purification.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

LLV is consultant of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. for HPV vaccines. None of the other authors have conflicts of interest to report.

Authors’ contributions

LLV and LS were the principal and co-principal investigators, conceived and designed the study, and made drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. JCB, MAA, SF, JSS, LT and RALN wrote the protocols, conducted all molecular analysis and participated in the interpretation of the data. Sample collection was undertaken by HOOC, LLM, LGB, CRC, MAK, FRP, AJG, MBM, LS and LMR. Pathologic analysis was conducted by SF and ESM. LLM did the statistical analysis and interpretation. All authors read, critically revised and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Betiol, J.C., Sichero, L., Costa, H.O.d.O. et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus types and variants and p16INK4a expression in head and neck squamous cells carcinomas in São Paulo, Brazil. Infect Agents Cancer 11, 20 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13027-016-0067-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13027-016-0067-8