Abstract

Background

Implementation of new practices in team-based settings requires teams to work together to respond to new demands and changing expectations. However, team constructs and team-based implementation approaches have received little attention in the implementation science literature. This systematic review summarizes empirical research examining associations between teamwork and implementation outcomes when evidence-based practices and other innovations are implemented in healthcare and human service settings.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, CINAHL, APA PsycINFO and ERIC for peer-reviewed empirical articles published from January 2000 to March 2022. Additional articles were identified by searches of reference lists and a cited reference search for included articles (completed in February 2023). We selected studies using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods to examine associations between team constructs and implementation outcomes in healthcare and human service settings. We used the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool to assess methodological quality/risk of bias and conducted a narrative synthesis of included studies. GRADE and GRADE-CERQual were used to assess the strength of the body of evidence.

Results

Searches identified 10,489 results. After review, 58 articles representing 55 studies were included. Relevant studies increased over time; 71% of articles were published after 2016. We were unable to generate estimates of effects for any quantitative associations because of very limited overlap in the reported associations between team variables and implementation outcomes. Qualitative findings with high confidence were: 1) Staffing shortages and turnover hinder implementation; 2) Adaptive team functioning (i.e., positive affective states, effective behavior processes, shared cognitive states) facilitates implementation and is associated with better implementation outcomes; Problems in team functioning (i.e., negative affective states, problematic behavioral processes, lack of shared cognitive states) act as barriers to implementation and are associated with poor implementation outcomes; and 3) Open, ongoing, and effective communication within teams facilitates implementation of new practices; poor communication is a barrier.

Conclusions

Teamwork matters for implementation. However, both team constructs and implementation outcomes were often poorly specified, and there was little overlap of team constructs and implementation outcomes studied in quantitative studies. Greater specificity and rigor are needed to understand how teamwork influences implementation processes and outcomes. We provide recommendations for improving the conceptualization, description, assessment, analysis, and interpretation of research on teams implementing innovations.

Trial registration

This systematic review was registered in PROSPERO, the international prospective register of systematic reviews. Registration number: CRD42020220168.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Healthcare and human service providers (e.g., clinicians, case managers) often work in team-based settings where professionals work collaboratively with one another and service recipients toward shared goals [1, 2]. Team-based care is intended to include multiple professionals with varying skills and expertise [1, 3]. It requires shared responsibility for outcomes and increases team members’ dependence on one another to complete work [1, 3, 4]. Effective team-based care and higher quality teamwork are associated with improvements in care access and quality, patient safety, patient satisfaction, clinical outcomes, and costs [2, 4,5,6,7,8,9].

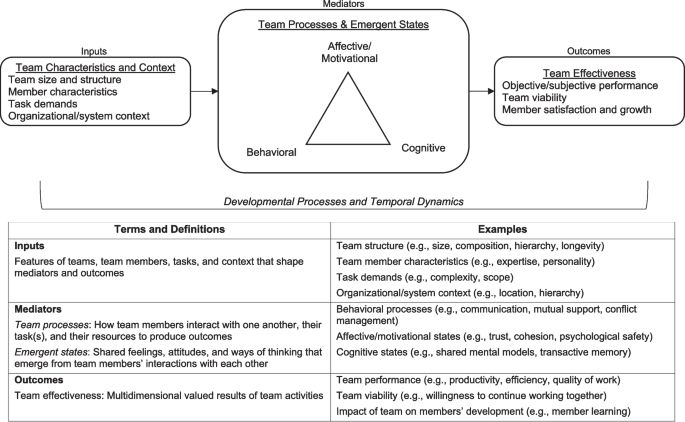

We use the term ‘teamwork’ to refer to an array of team constructs using the input-mediator-outcome-input (IMOI) framework (Fig. 1) [10,11,12]. The IMOI framework recognizes that team interactions are dynamic and complex, with processes unfolding over time and feedback loops between processes, outcomes, and inputs [10]. Team inputs include team structure and composition, task demands, and contextual features [13]. Mediators are aspects of team functioning (i.e., what team members think, feel, and do [12]) through which inputs influence outcomes. These processes and emergent states may be cognitive, affective, or behavioral [5, 14,15,16]. Team effectiveness outcomes are multidimensional and include team performance as well as team viability and the impact of the team on members’ development [12, 17,18,19].

Conceptual model of team effectiveness and key terminology. Figure adapted from “Advancing research on teams and team effectiveness in implementation science: An application of the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework” by E.A. McGuier, D.J. Kolko, N.A. Stadnick, L. Brookman-Frazee, C.B. Wolk, C.T. Yuan, C.S. Burke, & G.A. Aarons, 2023, Implementation Research and Practice, 4, 26334895231190855. [CC BY-NC]

Implementation of new practices in team-based service settings requires team members to work together to respond to changing demands and expectations. Extensive research has identified barriers and facilitators to implementation of new practices at the individual provider, organization, and system levels; however, the team level has received little empirical attention [20, 21]. This is a problem because implementation efforts increasingly rely on teams, and responses to a new practice are likely to be influenced by team characteristics and processes. See McGuier and colleagues [20] for an overview of team constructs in the context of implementation science and the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework [22, 23]. Given increasing use of team-based care and interest in implementation strategies targeting teams, examining how teamwork is associated with implementation processes and outcomes is critical. This systematic review identified and summarized empirical research examining associations between teamwork and implementation outcomes when evidence-based practices (EBPs) and other innovations were implemented in healthcare and human service settings.

Methods

This systematic review was registered (PROSPERO; registration number: CRD42020220168) and conducted following the published protocol [24]. The review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA and SWiM guidance [25, 26]; relevant checklists are in Additional File 1.

Information sources and search strategy

We searched the following databases: MEDLINE (Ovid), CINAHL (Ebsco), APA PsycINFO (Ovid), and ERIC (Ebsco). Database searches were run on August 7, 2020, and again on March 8, 2022. For all searches, a publication date from 2000 to current was applied; there were no language restrictions (see [24]). An experienced health sciences librarian (MLK) designed the Ovid MEDLINE search and translated that search for use in the other databases (see additional file in [24]). The search strings consisted of controlled vocabulary (when available) and natural language terms representing concepts of teamwork and implementation science or innovation or evidence-based practice. Results were downloaded to an EndNote (version X9.3.3) library and duplicate records removed [27]. Additional relevant articles were identified by hand searches of reference lists of included articles, a cited reference search for included articles in the Web of Science (Clarivate) bibliographic database (completed in February 2023), and requests sent to implementation science listservs and centers for suggestions of relevant articles.

Eligibility criteria

We included empirical journal articles describing studies using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods. Study protocols, reviews, and commentaries were excluded. All studies were conducted in healthcare or human service settings (e.g., hospitals, clinics, child welfare) and described the implementation of a practice to improve patient care. Studies of interventions to improve teamwork (e.g., team building interventions) and studies of teams created to implement the innovation (e.g., quality improvement teams, implementation support teams) were excluded. Eligible studies assessed at least one team construct and described its influence on implementation processes and outcomes.

Changes from protocol

Several changes were made from our systematic review protocol (PROSPERO CRD42020220168; [24]). Specifically, during the full-text review stage, we broadened the scope from team functioning (i.e., processes and states) to include team structure and performance because of the small number of studies that assessed and reported specific processes or states. This change increased the number of included studies. Similarly, because implementation outcomes were often inconsistently defined and poorly reported [28,29,30], we broadened our scope to include studies that identified team constructs as implementation determinants (i.e., barriers/facilitators) without explicitly defining and measuring an implementation outcome. Because of changes in university access to bibliographic databases, the cited reference search was performed in the Web of Science only instead of the Web of Science and Scopus. This bibliographic database indexes more than 21,000 scientific journals [31]. Lastly, because of time and resource constraints, we did not search conference abstracts or contact authors for unreported data.

Selection process and data extraction

Title/abstract screening and review of full-text articles were conducted by pairs of trained independent reviewers in DistillerSR. Conflicts were resolved through re-review, discussion between reviewers, and when needed, discussion with a senior team member (EAM). A final review of all included articles was conducted by EAM. Relevant data from each article was extracted into an Excel spreadsheet by one reviewer (AS). A second reviewer (EAM) conducted a line-by-line review and verification. Our data extraction form was informed by existing forms and guides (e.g., [32, 33]). For each included study, we extracted information on measures of teamwork and implementation-relevant outcomes, characteristics of the setting, teams, and participants, analysis methods, and results. For quantitative studies, we recorded correlation coefficients and/or regression coefficients as standardized metrics of association. For qualitative studies, we recorded themes [33].

Quality and risk of bias assessment

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [34] was used to evaluate quality and risk of bias for each included study. Multiple publications from the same study were evaluated separately because they reported different outcomes. Consistent with Powell and colleagues [35], quality evaluations were only made for the components of the study relevant to our question. Quality evaluations were conducted by two independent reviewers (EAM, MAD) with discrepancies resolved through consensus discussion. After completing the MMAT, the reviewers jointly categorized each article as high, moderate, or low quality. High quality studies were those with affirmative responses to all MMAT questions. Moderate quality studies had at least one minor methodological problem, and low-quality studies had serious flaws (e.g., qualitative studies with poor coherence between data, analysis, and conclusions; quantitative studies with biased samples and/or inappropriate statistical analyses).

We rated the relevance of each publication to our research question as high, moderate, or low. Highly relevant studies reported implementation of a well-defined innovation, thoroughly described team constructs and implementation outcomes, and clearly linked team constructs to implementation outcomes. Most studies rated as low relevance provided very limited information about teamwork and/or implementation outcomes. Studies that only described barriers/facilitators were rated as low or moderate relevance. Ratings were conducted by two independent reviewers (EAM, CBW) with discrepancies resolved through consensus discussion.

Data synthesis

We conducted a narrative synthesis of included studies following guidelines for synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) [36]. We prioritized reporting of high quality, highly relevant studies. Studies categorized as low quality and/or low relevance were not included in the synthesis but are included in the description of study characteristics to convey the breadth of the literature. We organized studies based on the IMOI framework (i.e., team inputs, processes/states, and outputs) and organized studies of processes/states by affective, behavioral, and cognitive constructs when possible. Because of the heterogeneity in team constructs and implementation outcomes, we were unable to quantitatively synthesize results using meta-analysis or formally investigate heterogeneity; this challenge is common in implementation science systematic reviews [30]. We assessed the strength of the overall body of evidence with GRADE for quantitative studies [37] and GRADE-CERQual for qualitative studies [38, 39]. GRADE results in ratings of high, moderate, low, or very low quality of evidence for each outcome of interest. GRADE-CERQual results in ratings of high, moderate, low, or very low confidence in each review finding. GRADE ratings were made independently with discrepancies resolved through consensus discussion; GRADE-CERQual ratings were made through iterative discussions as recommended [39]. All ratings and decisions were made by the first and senior authors.

Results

Search results

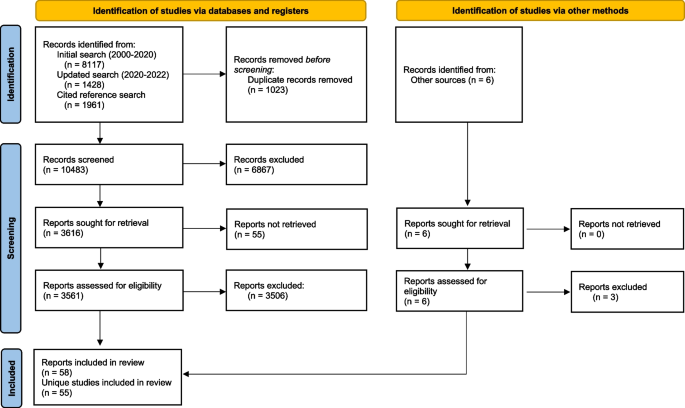

Our initial search, after removal of duplicates, yielded 7181 results. The second search (August 2020-March 2022) captured an additional 1341 results. The cited reference search yielded 1961 results. A total of 10,489 results were included in title/abstract review. Figure 2 provides a PRISMA flow diagram for included studies. After full-text review, 58 articles from 55 studies were included in analyses [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97].

PRISMA flow diagram of included articles. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

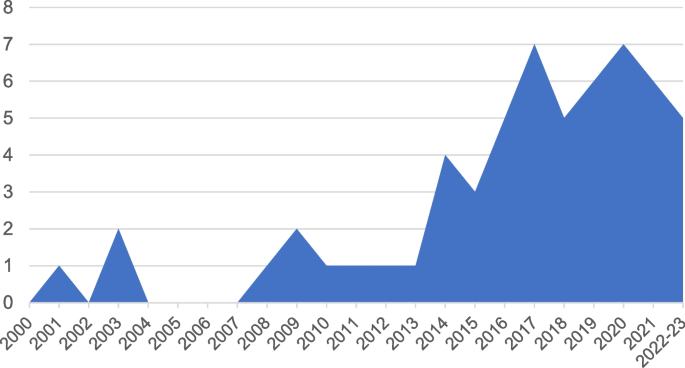

As shown in Fig. 3, publications on teamwork and implementation have increased substantially since 2000. Three articles on this topic (5%) were published between 2000 and 2007, 14 (24%) between 2008 and 2015, and 41 (71%) between 2016 and early 2023.

Study characteristics

Interrater agreement was good for assessment of study quality (81% agreement on MMAT questions) and ratings of relevance (88% agreement). There were 20 high quality articles, 23 moderate quality articles, and 15 low quality articles. Fourteen articles were rated as high relevance, 22 as moderate, and 22 as low relevance. Only 4 were rated as both high quality and high relevance. We report study characteristics for all 58 eligible articles. Our narrative synthesis includes 32 articles categorized as moderate/high quality and moderate/high relevance; it excludes 26 articles categorized as low quality and/or relevance.

Studies were conducted in inpatient healthcare (n = 22), outpatient/ambulatory healthcare (n = 21), mental health settings (n = 9), and other settings (e.g., residential facilities, multiple settings; n = 6). There were 33 qualitative, 15 quantitative, and 10 mixed methods studies. All quantitative studies were descriptive observational studies.

Most studies examined team processes/states (n = 53); fewer examined team inputs (n = 27). Only two studies examined a team effectiveness outcome. The most common implementation outcomes were fidelity (n = 16) and other specified implementation outcomes (e.g., “extent of use,” “implementation success”) (n = 15). Less frequently identified implementation outcomes included adoption (n = 5), sustainment (n = 4), reach (n = 4), and perceptions of the innovation (e.g., acceptability, appropriateness, feasibility; n = 3). Approximately one-third of studies (n = 21) did not report specific implementation outcomes but described implementation determinants (i.e., barriers and facilitators).

Synthesis: team inputs & implementation outcomes

Team inputs examined in studies included team stability/instability and staffing shortages, aspects of team structure and composition, interdependence, and hierarchy and professional roles. Quantitative findings are presented in Table 1. A CERQual Summary of Qualitative Findings related to team inputs is shown in Table 2. A CERQual Evidence Profile is provided in Additional File 2 (Table A1).

Team stability/instability and staffing shortages

Team stability/instability (i.e., consistency in membership over time) was examined in one mixed methods study [48, 49] and three qualitative studies [70, 81, 94]. A study of surgical teams found variations in membership stability but no association between stability and “implementation success” (i.e., composite measure based on number of uses of new technique, proportion of uses, and changes in use) [48, 49]. The authors suggested that stability facilitates the development of team coordination but that selecting small and exclusive teams may limit the spread of innovations within the organization. Another study found that a dedicated and stable team in which members were selected and trained together in the use of a new surgical technique led to quicker uptake and better integration into practice, theorizing that dedicated and stable teams increased trust, motivation, and collaborative problem-solving [81]. However, dedicated teams were difficult to sustain, and some sites instead used rotating team members from a larger pool of trained staff. In rural primary care, stability of team members facilitated sustainment of memory care clinics [70]. Lastly, another study in primary care found mixed perceptions of stable vs. rotating staff when adding a new team role (i.e., health coach); some team members liked rotating through different roles while others wanted more stability [94]. Across studies, we found that dedicated and stable team members facilitate implementation while instability in team membership is a barrier to implementation (moderate confidence).

Qualitative studies identified staffing shortages and turnover on teams as barriers to implementation [50, 67, 75, 78, 92]. In Veterans Health Administration (VA) clinics, “inadequate staffing posed an insurmountable barrier,” hindering communication and delivery of optimal care during the implementation of the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model [92]. Similarly, staff shortages, turnover, and high workloads hindered guideline implementation in Kenyan hospitals [75]. Two studies found negative impacts of staffing shortages and turnover on sustainment. Staff turnover contributed to discontinuity in Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) team members [78], and appropriate staffing (i.e., ensuring manageable workloads) and blocking time for team members were identified as critical to sustainment of a team-based model in the VA [67]. We found that staffing shortages and turnover hinder implementation (high confidence).

Team structure/composition

Studies examined multiple aspects of team structure and composition, specifically team size, workload, longevity (i.e., how long team members had worked together), history of change, and team member characteristics. Team size was examined in two studies of DBT. In a mixed methods study, team size was positively correlated with fidelity, and qualitative data suggested that team size may increase as a result of successful implementation [47]. In contrast, another study found that DBT team size was not associated with the number of DBT components adopted and was negatively associated with reach, suggesting reach may reflect high workloads [72]. In VA mental health clinics, team workload (i.e., number of patients seen) was negatively associated with sustainment of trauma-focused therapies [68]. In these studies, team longevity and history of change were not associated with implementation outcomes [47, 68]. Team member characteristics, specifically team member competency/expertise, experience, and commitment/engagement, were identified as facilitators of implementation in some qualitative studies [40, 70, 81, 84, 95].

Overall, few findings could be made from quantitative studies examining team structure and composition. Two studies of team size found mixed results, and workload, longevity, and history of change were examined in only one study each. Across qualitative studies, we found team member competency/expertise, experience, and commitment/engagement facilitate implementation (moderate confidence).

Team interdependence

One quantitative study examined team interdependence [65]. In multidisciplinary child abuse teams implementing a mental health screening/referral protocol, task interdependence (i.e., reliance on team members to share resources and coordinate workflows) was positively associated with reach but not time to adoption. Outcome interdependence (i.e., extent to which outcomes are evaluated at the team vs. individual level) was significantly negatively correlated with time to adoption but not reach. Neither task nor outcome interdependence were associated with team members’ perceptions of acceptability, appropriateness, or feasibility of the innovation [65]. Because only one study examined interdependence, no review findings were made.

Hierarchy & professional roles

Hierarchy, power distributions, and rigid roles were identified as barriers to implementation in several qualitative studies [50, 53, 74, 97]. Flatter hierarchies (i.e., more equal distribution of power and authority) supported guideline implementation in pediatric primary care; practices with low compliance to guidelines had more hierarchical relationships while practices with high compliance had more shared decision-making [97]. In a setting with hierarchy and rigid division of roles, nurses trained in an innovation reported concern that their decisions would be questioned by physicians without expertise in the innovation but more authority [74]. Similarly, in surgical teams, rigid professional roles and a hierarchical team culture constrained open discussion and created contention over how and when a “time-out” should be completed, resulting in inconsistent use and poor fidelity [50, 53]. Across studies, we found that in multidisciplinary settings, rigid professional roles, hierarchical relationships, and power differentials are barriers to implementation (moderate confidence).

Summary of team inputs & implementation outcomes

There was no overlap among team input variables and implementation outcomes examined in quantitative studies (Table 1). Accordingly, we were unable to generate estimates of effects or ratings of evidence quality. Qualitative review findings are shown in Table 2. We found: 1) Dedicated and stable team members facilitate implementation while instability in team membership is a barrier to implementation (moderate confidence); 2) Staffing shortages and turnover hinder implementation (high confidence); 3) Team member competency/expertise, experience, and commitment/engagement facilitate implementation (moderate confidence); and 4) In multidisciplinary settings, rigid professional roles, hierarchical relationships, and power differentials are barriers to implementation (moderate confidence).

Synthesis: team processes/states & implementation outcomes

Studies examined overall team functioning as well as specific affective states, behavioral processes, and cognitive states. Quantitative findings are presented in Table 3, and a GRADE Evidence Profile is provided in Additional File 2 (Table A2). A CERQual Summary of Qualitative Findings related to team processes and states is shown in Table 4. A CERQual Evidence Profile is provided in Additional File 2 (Table A3).

Overall team functioning

Nine studies examined quantitative associations between overall team functioning and implementation outcomes. Team functioning was positively associated with intervention fidelity in 2 of 3 studies. One study examined implementation of transition programs for adolescents with chronic health conditions in 29 teams. More positive team climate, measured by the Team Climate Inventory (i.e., shared vision, participative safety, task orientation, support for innovation), at study start was associated with greater improvements in quality of chronic care delivery one year later [45]. Additionally, improvements in team climate were associated with greater improvement in care delivery [45]. These findings were consistent across teams working with different patient populations, suggesting the influence of team climate generalizes across teams and settings [45]. Greater team climate for innovation was also associated with greater fidelity (i.e., implementation of more program elements) among DBT teams [47]. In contrast, no significant associations were found between team climate and fidelity to a multifaceted cardiovascular disease management intervention, with qualitative data suggesting variation in the influence of teamwork across practices [77]. There was no overlap in the metrics of association reported in these studies; therefore, we were unable to generate an estimate of the effect of team functioning on fidelity. The quality of the evidence for fidelity was rated very low because of serious methodological limitations, serious inconsistency, and very serious imprecision due to the small number of studies.

Three studies examined associations between teamwork and adoption, with no significant associations found. The first study found that teamwork climate (i.e., perceived quality of collaboration between personnel) was not significantly associated with adoption of a comprehensive safety program in intensive care units, although there were associations between adoption and organizational constructs (e.g., lower safety climate, more management support) [59]. In a study of DBT teams, neither positive nor negative team functioning was associated with the number of DBT modes adopted [72]. The third study assessed relational coordination (i.e., shared goals, communication, respect) in primary care practices implementing patient engagement strategies. Relational coordination was high across practices initially and did not differ for practices with high vs. low adoption, although it increased over time in practices with high adoption [83]. There was no overlap in the metrics of association reported in these studies; therefore, we were unable to generate an estimate of the effect of team functioning on adoption. The quality of the evidence was rated very low because of serious methodological limitations and very serious imprecision due to the small number of studies.

Reach and sustainment were each examined in one quantitative study. DBT teams with more negative functioning had greater reach, suggesting that reach may reflect high workloads; positive functioning was not associated with reach [72]. In VA mental health clinics, team functioning was positively correlated with sustainment of evidence-based trauma-focused psychotherapies and significantly associated with sustainment after controlling for covariates [68]. Two studies examined other implementation outcomes. One found that better team functioning was associated with greater implementation of changes to improve access to care in VA clinics [62]. In the other, primary care practices reporting better teamwork were more likely to be in later stages of transformation to PCMHs than practices with poorer teamwork [88]. Because of the small number of studies examining reach, sustainment, and other implementation outcomes, we were unable to generate estimates of effects or ratings of evidence quality for these outcomes.

Our qualitative review findings are based on 12 studies describing how team functioning influenced implementation processes and outcomes. There was considerable variation across studies in how team functioning was defined and what implementation outcomes were examined. Most findings were based on relatively thin and superficial data. Studies occurred in a variety of healthcare settings with varying resources and implemented diverse interventions. We found with high confidence that 1) Adaptive team functioning, characterized by positive affective states (e.g., trust, mutual respect, belonging), effective behavior processes (e.g., frequent communication and coordination), and shared cognitive states (e.g., clear roles, shared mental models of how to provide care), facilitates implementation and is associated with better implementation outcomes; and 2) Problems in team functioning, including negative affective states (e.g., tension, lack of trust), problematic behavioral processes (e.g., conflict, competition, poor communication), and a lack of shared cognitive states (e.g., unclear roles, lack of shared awareness, competing goals), act as barriers to implementation and are associated with poor implementation outcomes.

Affective states

Specific affective states were examined in one quantitative study, three mixed methods studies, and one qualitative study. There was no overlap in the associations between affective states and implementation outcomes reported in quantitative studies (Table 3). In a study of multidisciplinary teams responding to child abuse, affective integration (i.e., liking, trust, respect) was positively associated with acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility but not time to adoption or reach [65]. In DBT teams, cohesion was associated with fidelity, and qualitative data indicated that liking one’s team members and having a shared team identity were critical to effective implementation [47]. Another study of DBT teams described conflicts and lack of safety and trust within teams resulting in their dissolution [78].

Edmondson and colleagues found that psychological safety and ease of speaking up (i.e., interpersonal climate that allows members to share questions and concerns) were associated with implementation success [48, 49]. In teams with low psychological safety, lower-status team members were hesitant to speak up, hindering change and proficiency in the new practice [49]. Psychological safety was closely related to learning behavior within the team, including speaking up with questions and concerns [48, 49]. From the mixed methods and qualitative studies, we found that trust, cohesion, and psychological safety within teams facilitate implementation by contributing to team members’ willingness to speak up and share experiences and feedback. Negative affective states, fear of judgment, conflict, and lack of safety hinder implementation (moderate confidence).

Behavioral processes

Specific behavioral processes, including communication, learning behavior, and coordination, were examined in two quantitative studies, two mixed methods studies, and five qualitative studies. There was no overlap in the associations between behavioral processes and implementation outcomes reported in quantitative studies (Table 3).

Only one study reported quantitative findings for communication. Communication in DBT teams was positively associated with fidelity [47]. Qualitative studies frequently identified communication as a determinant of implementation (Table 4). From qualitative studies, we found that open, ongoing, and effective communication within teams facilitates implementation of new practices; poor communication is a barrier (high confidence).

Quantitative associations between team learning behavior and implementation outcomes were reported in three studies. Team learning behavior in child abuse teams was positively correlated with acceptability and feasibility; it was not associated with appropriateness, time to adoption, or reach [65]. Learning behavior was positively associated with knowledge and use of innovations in nursing teams [91] and with implementation success in surgical teams [48]. Because each of these studies examined different implementation outcomes, we were unable to generate an estimate of the effect of learning behavior or rate evidence quality.

Inter-team communication, specifically speaking up and learning from other teams (i.e., boundary spanning), was identified as a critical part of team learning processes associated with successful implementation [48]. Communication beyond the team was also identified as a facilitator of implementation in two qualitative studies [47, 75]. We found that communication beyond the team facilitates implementation by providing opportunities for team learning (low confidence).

Lastly, two qualitative studies examined coordination among healthcare teams [40, 95]. Findings were somewhat ambiguous and based on thin data. We found with low confidence that poor coordination among healthcare professionals interferes with providing high-quality care and can be a barrier to implementation of new approaches (low confidence).

Cognitive states

Specific cognitive states were examined in two quantitative studies. There was no overlap in the associations between cognitive states and implementation outcomes reported (Table 3). The first study found no significant associations between shared goals and implementation outcomes [65]. The second study found that greater team knowledge and skills were associated with greater implementation of key changes to improve access to care; team problem recognition was not associated with implementation [62].

Two studies reported qualitative findings related to shared goals. In VA mental health teams, shared mission differentiated teams with sustained high reach of EBPs from those with low reach [84]. Commitment to a shared goal consistent with the EBP supported sustainment [84]. Similarly, shared goals and vision were identified as a facilitator of DBT programs [47]. We found that shared goals, mission, and vision within teams facilitate implementation and sustainment (low confidence).

Summary of team processes/states & implementation outcomes

There was very little overlap in the reported associations between team processes/states and implementation outcomes (Table 3). We were unable to generate estimates of effects for any associations. When there was sufficient overlap to rate evidence quality, the evidence was rated very low quality (Table A2, Additional File 2).

Qualitative review findings are shown in Table 4. We found the following: 1) Adaptive team functioning, characterized by positive affective states (e.g., trust, mutual respect, belonging), effective behavior processes (e.g., frequent communication and coordination), and shared cognitive states (e.g., clear roles, shared mental models of how to provide care), facilitates implementation and is associated with better implementation outcomes (high confidence); 2) Problems in team functioning, including negative affective states (e.g., tension, lack of trust), problematic behavioral processes (e.g., conflict, competition, poor communication), and a lack of shared cognitive states (e.g., unclear roles, lack of shared awareness, competing goals), act as barriers to implementation and are associated with poor implementation outcomes (high confidence); 3) Trust, cohesion, and psychological safety within teams facilitate implementation by contributing to team members’ willingness to speak up and openly share experiences and feedback. Negative affective states, fear of judgment, conflict, and lack of safety hinder implementation (moderate confidence); 4) Open, ongoing, and effective communication within teams facilitates implementation of new practices; poor communication is a barrier (high confidence); 5) Communication beyond the team facilitates implementation by providing opportunities for team learning (low confidence); 6) Poor coordination among healthcare professionals interferes with providing high-quality care and can be a barrier to implementation of new approaches (low confidence); and 7) Shared goals, mission, and vision within teams facilitate implementation and sustainment (low confidence).

Synthesis: team effectiveness outcomes & implementation outcomes

Team effectiveness outcomes are multidimensional and include performance (i.e., productivity, efficiency, and quality of the team’s work), team viability, and the impact of the team on members’ development [12, 17,18,19]. Only two studies examined associations between team effectiveness and implementation outcomes. Quantitative findings are presented in Table 5. One quantitative study found that team members’ ratings of team performance were associated with innovation acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility; performance was not associated with time to adoption or reach [65]. One qualitative study found that positive outcomes for team members (e.g., increased comfort working together, greater knowledge) were associated with sustainment [70]. No studies examined associations of team viability and implementation outcomes.

Summary of team effectiveness outcomes & implementation outcomes

Only one quantitative study examined associations between a dimension of team effectiveness and implementation outcomes (Table 5). Accordingly, we were unable to generate ratings of evidence quality or estimates of any effects. Similarly, because there was only one qualitative study, we were unable to make a review finding.

Discussion

This systematic review summarizes over 20 years of empirical literature on the associations between teamwork and implementation outcomes in the context of implementation of new practices in health and human services. Consistent with increased attention to teams and reliance on team-based models of care, as well as the growth of implementation science, studies increased substantially over time. We included studies that used quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods, yielding a total of 58 articles representing 55 studies. Included studies spanned naturalistic implementation evaluations and planned implementation research.

Key findings with high confidence were: 1) Staffing shortages and turnover hinder implementation, 2) Adaptive team functioning, characterized by positive affective states, effective behavior processes, and shared cognitive states, facilitates implementation and is associated with better implementation outcomes. Problems in team functioning, including negative affective states, problematic behavioral processes, and a lack of shared cognitive states, act as barriers to implementation and are associated with poor implementation outcomes, and 3) Open, ongoing, and effective communication within teams facilitates implementation of new practices; poor communication is a barrier. Our results generally align with conventional wisdom and scientific research outside of healthcare, increasing confidence in the findings. Team effectiveness and change management research in other types of organizations and settings (e.g., military, aviation, space exploration) [98,99,100,101,102,103] is largely converging.

Overall, the literature was heterogeneous, and many studies lacked specificity regarding team composition and implementation activities and outcomes. Teamwork was defined and measured inconsistently and with limited precision across studies, which hindered our ability to draw conclusions about how teams influence implementation processes and outcomes. There was also poor measurement and reporting of implementation outcomes in many studies, consistent with a recent review of research on implementation outcomes [28, 29]. Many studies used broad measures encompassing multiple dimensions of teamwork. Among studies that assessed specific team processes and states, there was very little overlap across constructs assessed. Qualitative studies identified a rich array of specific team processes and states; research to confirm the presence of these factors in other settings and determine their associations with implementation outcomes is needed.

In Table 6, we summarize the limitations of existing research on teams and implementation and provide recommendations for future research. Notably, increased specificity and rigor in how teamwork is conceptualized and assessed is needed to advance our understanding of how teamwork affects implementation processes and outcomes. Limited inclusion of teams and team constructs in implementation theories, models, and frameworks has likely contributed to the neglect of teams in implementation science [20]. Updates to theories, models, and framework should consider integrating teams and team-level constructs [20]. In addition, there are well-established theories of team effectiveness that could inform hypotheses about how specific team constructs affect implementation [104,105,106,107].

There is considerable room for improvement in the definition and description of teams and analysis of data from teams. Describing the structure and purpose of teams, as well as interdependencies within the team, can help differentiate teams from groups of individuals who do not constitute a team, an important conceptual distinction that can be difficult to discern in study descriptions. Reporting of sampling and recruitment procedures for teams and team-level response rates is needed. For quantitative studies, use of standardized, validated measures of teamwork constructs is recommended. Researchers should be careful to base inferences about teams on team-level data. Lastly, future research should follow recommendations for improving measurement and reporting of implementation outcomes [29, 108] and consider the multilevel context of teams in theory, measurement, analysis, and interpretation of results [109].

Limitations

As with all systematic reviews, it is possible that we failed to identify some relevant articles or data. We did not search gray literature or conference abstracts or contact authors for unreported data. Our organization of studies by the IMOI framework is likely imperfect given the broad array of team constructs included and poor reporting in many studies. We included diverse innovations intended to improve patient care, including specific EBPs, clinical practice guidelines, models of care, care bundles, procedural changes, and technological innovations. This diversity in objects of implementation reflects ongoing debates about the necessary strength of evidence for objects of implementation and varying thresholds in different contexts [110]. In this review, high quality studies tended to involve clinical interventions with strong research evidence (e.g., DBT) and clinics in structured and often team-based healthcare systems (e.g., VA). Diversity of innovations and settings provides greater external validity for our findings but may mask some findings specific to certain innovations or settings.

We only included studies of existing teams providing clinical services, however, many studies provided limited descriptions of teams, and in some cases the distinction between clinical teams and implementation/quality improvement teams was unclear. There is increasing attention to use of teams in implementation frameworks [20, 111] and evidence that functioning of implementation teams matters [112, 113]. Research on the composition and functioning of implementation teams is an important area for future research.

Conclusions

Our systematic review findings indicate that teamwork matters for implementation. However, greater specificity and rigor are needed to advance our understanding of how teamwork influences implementation processes and outcomes. We provide recommendations for improving the conceptualization, description, assessment, analysis, and interpretation of research on teams implementing new practices.

Availability of data and materials

All data cited in this review came from published papers and are therefore already available. The data created as part of the review process are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Mitchell P, Wynia M, Golden R, McNellis B, Okun S, Webb CE, et al. Core principles and values of effective team-based health care. NAM Perspectives. 2012. Available from: https://nam.edu/perspectives-2012-core-principles-values-of-effective-team-based-health-care/ Cited 2020 Sep 23

Reiss-Brennan B, Brunisholz KD, Dredge C, Briot P, Grazier K, Wilcox A, et al. Association of integrated team-based care with health care quality, utilization, and cost. JAMA. 2016;316(8):826–34.

Katkin JP, Kressly SJ, Edwards AR, Perrin JM, Kraft CA, Richerson JE, et al. Guiding principles for team-based pediatric care. Pediatrics. 2017;140(2):e20171489.

Lipton HL. Home is where the health is: Advancing team-based care in chronic disease management. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1945–8.

Dinh JV, Traylor AM, Kilcullen MP, Perez JA, Schweissing EJ, Venkatesh A, et al. Cross-disciplinary care: A systematic review on teamwork processes in health care. Small Group Research. 2020;51(1):125–66.

Fiscella K, McDaniel SH. The complexity, diversity, and science of primary care teams. Am Psychol. 2018;73(4):451–67.

Herbert JL, Bromfield LM. A quasi-experimental study of the Multi-Agency Investigation & Support Team (MIST): A collaborative response to child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;27:104827.

Reiss-Brennan B. Mental Health Integration: Normalizing Team Care. J Prim Care Community Health. 2014;5(1):55–60.

Schmutz J, Manser T. Do team processes really have an effect on clinical performance? A systematic literature review. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110(4):529–44.

Ilgen DR, Hollenbeck JR, Johnson M, Jundt D. Teams in organizations: From input-process-output models to IMOI models. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:517–43.

Kozlowski SWJ, Bell BS. Work groups and teams in organization. In: Borman WC, Ilgen DR, Klimoski RJ, editors. Handbook of Psychology (Vol 12): Industrial and Organizational Psychology. New York: Wiley-Blackwell. 2003. p. 333–75. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118133880.hop212017 Cited 2020 Apr 10

Mathieu JE, Maynard MT, Rapp T, Gilson L. Team effectiveness 1997–2007: A review of recent advancements and a glimpse into the future. J Manag. 2008;34(3):410–76.

Cordery JL, Tian AW. Team Design. In: The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of the Psychology of Team Working and Collaborative Processes. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 2017;p. 103–28. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118909997.ch5 Cited 2021 Apr 2

Kozlowski SWJ, Bell BS. Work groups and teams in organizations: Review update. In: Schmitt N, Highhouse S, editors. Handbook of Psychology (Vol 12): Industrial and Organizational Psychology. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2013. p. 111.

Kozlowski SWJ, Ilgen DR. Enhancing the effectiveness of work groups and teams. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2006;7(3):77–124.

Marks MA, Mathieu JE, Zaccaro SJ. A temporally based framework and taxonomy of team processes. AMR. 2001;26(3):356–76.

Hackman JR. A normative model of work team effectiveness. Arlington, VA: Office of Naval Research; 1983. Available from: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA136398 Cited 2022 May 16

Mathieu JE, Hollenbeck JR, van Knippenberg D, Ilgen DR. A century of work teams in the Journal of Applied Psychology. J Appl Psychol. 2017;102(3):452–67.

Rosen MA, Dietz AS. Team performance measurement. In: The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of the Psychology of Team Working and Collaborative Processes. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2017. p. 479–502.

McGuier EA, Kolko DJ, Stadnick NA, Brookman-Frazee L, Wolk CB, Yuan CT, et al. Advancing research on teams and team effectiveness in implementation science: An application of the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework. Implementation Research and Practice. 2023;1(4):26334895231190856.

Williams NJ, Beidas RS. Annual research review: The state of implementation science in child psychology and psychiatry: A review and suggestions to advance the field. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60:430–50.

Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(1):4–23.

Moullin JC, Dickson KS, Stadnick NA, Rabin B, Aarons GA. Systematic review of the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):1.

McGuier EA, Kolko DJ, Klem ML, Feldman J, Kinkler G, Diabes MA, et al. Team functioning and implementation of innovations in healthcare and human service settings: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):189.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339. Available from: http://www.bmj.com/content/339/bmj.b2535 Cited 2020 Apr 1

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;29(372):n71.

Bramer WM, Giustini D, de Jonge GB, Holland L, Bekhuis T. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016;104(3):240–3.

Lengnick-Hall R, Gerke DR, Proctor EK, Bunger AC, Phillips RJ, Martin JK, et al. Six practical recommendations for improved implementation outcomes reporting. Implement Sci. 2022;17(1):16.

Proctor EK, Bunger AC, Lengnick-Hall R, Gerke DR, Martin JK, Phillips RJ, et al. Ten years of implementation outcomes research: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2023;18(1):31.

Chapman A, Rankin NM, Jongebloed H, Yoong SL, White V, Livingston PM, et al. Overcoming challenges in conducting systematic reviews in implementation science: a methods commentary. Syst Rev. 2023;12(1):116.

Pranckutė R. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The Titans of Bibliographic Information in Today’s Academic World. Publications. 2021;9(1):12.

Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). Data collection form. EPOC Resources for review authors. Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services. 2013. Available from: http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-specific-resources-review-authors.

Noyes J, Lewin S. Extracting qualitative evidence. In: Noyes J, Booth A, Hannes K, Harden A, Harris J, Lewin S, et al., editors. Supplementary Guidance for Inclusion of Qualitative Research in Cochrane Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 1 (updated August 2011). Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group; 2011. Available from: http://cqrmg.cochrane.org/supplemental-handbook-guidance

Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, et al. Improving the content validity of the mixed methods appraisal tool: a modified e-Delphi study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;1(111):49-59.e1.

Powell BJ, Patel SV, Haley AD, Haines ER, Knocke KE, Chandler S, Determinants of implementing evidence-based trauma-focused interventions for children and youth: A systematic review. Adm Policy Ment Health, et al. cited 2020 Feb 20. Available from: 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-019-01003-3.

Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, Katikireddi SV, Brennan SE, Ellis S, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ. 2020;16(368):l6890.

Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction—GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2011;64(4):383–94.

Lewin S, Bohren M, Rashidian A, Munthe-Kaas H, Glenton C, Colvin CJ, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings—paper 2: how to make an overall CERQual assessment of confidence and create a Summary of Qualitative Findings table. Implementation Sci. 2018;13(1):11–23.

Lewin S, Booth A, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Rashidian A, Wainwright M, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: introduction to the series. Implementation Sci. 2018;13(1):1–10.

Adjognon OL, Shin MH, Steffen MJA, Moye J, Solimeo S, Sullivan JL. Factors affecting primary care implementation for older veterans with multimorbidity in Veterans Health Administration (VA). Health Serv Res. 2021;56(S1):1057–68.

Alidina S, Chatterjee P, Zanial N, Alreja SS, Balira R, Barash D, et al. Improving surgical quality in low-income and middle-income countries: why do some health facilities perform better than others? BMJ Qual Saf. 2021;30(12):937–49.

Boltey EM, Iwashyna TJ, Hyzy RC, Watson SR, Ross C, Costa DK. Ability to predict team members’ behaviors in ICU teams is associated with routine ABCDE implementation. J Crit Care. 2019;51:192–7.

Chenoweth L, Jeon YH, Stein-Parbury J, Forbes I, Fleming R, Cook J, et al. PerCEN trial participant perspectives on the implementation and outcomes of person-centered dementia care and environments. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(12):2045–57.

Costa DK, Valley TS, Miller MA, Manojlovich M, Watson SR, McLellan P, et al. ICU team composition and its association with ABCDE implementation in a quality collaborative. J Crit Care. 2018;44:1–6.

Cramm JM, Strating MMH, Nieboer AP. The role of team climate in improving the quality of chronic care delivery: a longitudinal study among professionals working with chronically ill adolescents in transitional care programmes. BMJ Open. 2014;4(5):e005369.

DePuccio MJ, Gaughan AA, Sova LN, MacEwan SR, Walker DM, Gregory ME, et al. An examination of the barriers to and facilitators of implementing nurse-driven protocols to remove indwelling urinary catheters in acute care hospitals. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2020;46(12):691–8.

Ditty MS, Landes SJ, Doyle A, Beidas RS. It takes a village: A mixed method analysis of inner setting variables and Dialectical Behavior Therapy implementation. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(6):672–81.

Edmondson AC. Speaking up in the operating room: How team leaders promote learning in interdisciplinary action teams. J Manage Stud. 2003;40(6):1419–52.

Edmondson AC, Bohmer RM, Pisano GP. Disrupted routines: Team learning and new technology implementation in hospitals. Adm Sci Q. 2001;46(4):685–716.

Gillespie BM, Chaboyer W, Wallis M, Fenwick C. Why isn’t “time out” being implemented? An exploratory study. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(2):103–6.

Gillespie BM, Harbeck E, Lavin J, Gardiner T, Withers TK, Marshall AP. Using normalisation process theory to evaluate the implementation of a complex intervention to embed the surgical safety checklist. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):170.

Gillespie BM, Marshall AP, Gardiner T, Lavin J, Withers TK. Impact of workflow on the use of the Surgical Safety Checklist: a qualitative study: Surgical Safety Checklist and work flow. ANZ J Surg. 2016;86(11):864–7.

Gillespie BM, Withers TK, Lavin J, Gardiner T, Marshall AP. Factors that drive team participation in surgical safety checks: a prospective study. Patient Saf Surg. 2016;10(3):1–9.

Gosling AS. Clinical team functioning and IT innovation: A study of the diffusion of a point-of-care online evidence system. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10(3):244–51.

Graetz I, Huang J, Brand R, Shortell SM, Rundall TG, Bellows J, et al. The impact of electronic health records and teamwork on diabetes care quality. American Journal of Managed Care. 2015;21(12):878–84.

Haider S, Ali RF, Ahmed M, Humayon AA, Sajjad M, Ahmad J. Barriers to implementation of emergency obstetric and neonatal care in rural Pakistan. Sawyer A, editor. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(11):e0224161.

Harvey C, Killaspy H, Martino S, White S, Priebe S, Wright C, et al. A comparison of the implementation of Assertive Community Treatment in Melbourne, Australia and London. England Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2011;20(2):151–61.

Harvey C, Killaspy H, Martino S, Johnson S. Implementation of Assertive Community Treatment in Australia: Model fidelity, patient characteristics and staff experiences. Community Ment Health J. 2012;48(5):652–61.

Hsu YJ, Marsteller JA. Who applies an intervention to influence cultural attributes in a quality improvement collaborative? J Patient Saf. 2020;16(1):1–6.

Irimu GW, Greene A, Gathara D, Kihara H, Maina C, Mbori-Ngacha D, et al. Explaining the uptake of paediatric guidelines in a Kenyan tertiary hospital – mixed methods research. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):119.

Lall D, Engel N, Devadasan N, Horstman K, Criel B. Team-based primary health care for non-communicable diseases: complexities in South India. Health Policy Plan. 2020;35(Supplement_2):ii22-34.

Lukas CV, Mohr D, Meterko M. Team effectiveness and organizational context in the implementation of a clinical innovation. Qual Manag Health Care. 2009;18(1):25–39.

Mariani E, Vernooij-Dassen M, Koopmans R, Engels Y, Chattat R. Shared decision-making in dementia care planning: barriers and facilitators in two European countries. Aging Ment Health. 2017;21(1):31–9.

Martinez RN, Hogan TP, Balbale S, Lones K, Goldstein B, Woo C, et al. Sociotechnical perspective on implementing clinical video telehealth for veterans with spinal cord injuries and disorders. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2017;23(7):567–76.

McGuier EA, Aarons GA, Byrne KA, Campbell KA, Keeshin B, Rothenberger SD, et al. Associations between teamwork and implementation outcomes in multidisciplinary cross-sector teams implementing a mental health screening and referral protocol. Implementation Science Communications. 2023;4(1):13.

Meloncelli N, Barnett A, de Jersey S. Staff resourcing, guideline implementation and models of care for gestational diabetes mellitus management. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;60(1):115–22.

Miller CJ, Kim B, Connolly SL, Spitzer EG, Brown M, Bailey HM, et al. Sustainability of the Collaborative Chronic Care Model in outpatient mental health teams three years post-Implementation: A qualitative analysis. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2023;50(1):151–9.

Mohr DC, Rosen CS, Schnurr PP, Orazem RJ, Noorbaloochi S, Clothier BA, et al. The influence of team functioning and workload on sustainability of trauma-focused evidence-based psychotherapies. PS. 2018;69(8):879–86.

Morgan D, Kosteniuk J, O’Connell ME, Kirk A, Stewart NJ, Seitz D, et al. Barriers and facilitators to development and implementation of a rural primary health care intervention for dementia: a process evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):709.

Morgan D, Kosteniuk J, O’Connell ME, Seitz D, Elliot V, Bayly M, et al. Factors influencing sustainability and scale-up of rural primary healthcare memory clinics: perspectives of clinic team members. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):148.

Munce SEP, Graham ID, Salbach NM, Jaglal SB, Richards CL, Eng JJ, et al. Perspectives of health care professionals on the facilitators and barriers to the implementation of a stroke rehabilitation guidelines cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):440.

Navarro-Haro MV, Harned MS, Korslund KE, DuBose A, Chen T, Ivanoff A, et al. Predictors of adoption and reach following Dialectical Behavior Therapy Intensive Training™. Community Ment Health J. 2019;55(1):100–11.

Newbould L, Ariss S, Mountain G, Hawley MS. Exploring factors that affect the uptake and sustainability of videoconferencing for healthcare provision for older adults in care homes: a realist evaluation. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2021;21(1):13.

Nyondo-Mipando AL, Woo Kinshella ML, Bohne C, Suwedi-Kapesa LC, Salimu S, Banda M, et al. Barriers and enablers of implementing bubble Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP): Perspectives of health professionals in Malawi. Ameh CA, editor. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(2):e0228915.

Nzinga J, Mbindyo P, Mbaabu L, Warira A, English M. Documenting the experiences of health workers expected to implement guidelines during an intervention study in Kenyan hospitals. Implementation Sci. 2009;4(1):44.

Papoutsi C, Poots A, Clements J, Wyrko Z, Offord N, Reed JE. Improving patient safety for older people in acute admissions: implementation of the Frailsafe checklist in 12 hospitals across the UK. Age Ageing. 2018;47(2):311–7.

Patel B, Usherwood T, Harris M, Patel A, Panaretto K, Zwar N, et al. What drives adoption of a computerised, multifaceted quality improvement intervention for cardiovascular disease management in primary healthcare settings? A mixed methods analysis using normalisation process theory. Implementation Sci. 2018;13(1):140.

Popowich AD, Mushquash AR, Pearson E, Schmidt F, Mushquash CJ. Barriers and facilitators affecting the sustainability of dialectical behaviour therapy programmes: A qualitative study of clinician perspectives. Couns Psychother Res. 2020;20(1):68–80.

Prom MC, Canelos V, Fernandez PJ, Gergen Barnett K, Gordon CM, Pace CA, et al. Implementation of integrated behavioral health care in a large medical center: Benefits, challenges, and recommendations. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2021;48(3):346–62.

Provost S, Pineault R, Grimard D, Pérez J, Fournier M, Lévesque Y, et al. Implementation of an integrated primary care cardiometabolic risk prevention and management network in Montréal: does greater coordination of care with primary care physicians have an impact on health outcomes? Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2017;37(4):105–13.

Randell R, Honey S, Alvarado N, Greenhalgh J, Hindmarsh J, Pearman A, et al. Factors supporting and constraining the implementation of robot-assisted surgery: a realist interview study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(6):e028635.

Robbins J, McAlearney AS. Encouraging employees to speak up to prevent infections: Opportunities to leverage quality improvement and care management processes. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44(11):1224–30.

Rodriguez HP, Poon BY, Wang E, Shortell SM. Linking practice adoption of patient engagement strategies and relational coordination to patient-reported outcomes in accountable care organizations. Milbank Q. 2019;97(3):692–735.

Sayer NA, Rosen CS, Bernardy NC, Cook JM, Orazem RJ, Chard KM, et al. Context matters: Team and organizational factors associated with reach of evidence-based psychotherapies for PTSD in the Veterans Health Administration. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2017;44(6):904–18.

Shin MH, Montano ARL, Adjognon OL, Harvey KLL, Solimeo SL, Sullivan JL. Identification of implementation strategies using the CFIR-ERIC matching tool to mitigate barriers in a primary care model for older veterans. Gerontologist. 2022;63(3):439–50.

Sopcak N, Aguilar C, O’Brien MA, Nykiforuk C, Aubrey-Bassler K, Cullen R, et al. Implementation of the BETTER 2 program: a qualitative study exploring barriers and facilitators of a novel way to improve chronic disease prevention and screening in primary care. Implementation Sci. 2016;11(1):158.

Steinmo SH, Michie S, Fuller C, Stanley S, Stapleton C, Stone SP. Bridging the gap between pragmatic intervention design and theory: using behavioural science tools to modify an existing quality improvement programme to implement “Sepsis Six.” Implementation Sci. 2016;11(1):14.

Stout S, Zallman L, Arsenault L, Sayah A, Hacker K. Developing high-functioning teams: Factors associated with operating as a “real team” and implications for patient-centered medical home development. Inquiry. 2017;12(54):0046958017707296.

Svensson B, Hansson L, Markström U, Lexén A. What matters when implementing Flexible Assertive Community Treatment in a Swedish healthcare context: A two-year implementation study. Int J Ment Health. 2017;46(4):284–98.

Tadyanemhandu C, van Aswegen H, Ntsiea V. Barriers and facilitators to implementation of early mobilisation of critically ill patients in Zimbabwean and South African public sector hospitals: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;44(22):6699–709.

Timmermans O, Van Linge R, Van Petegem P, Van Rompaey B, Denekens J. A contingency perspective on team learning and innovation in nursing: Team learning and innovation in nursing teams. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(2):363–73.

Tuepker A, Kansagara D, Skaperdas E, Nicolaidis C, Joos S, Alperin M, et al. “We’ve not gotten even close to what we want to do”: A qualitative study of early patient-centered medical home implementation. J GEN INTERN MED. 2014;29(S2):614–22.

van Bruggen S, Kasteleyn MJ, Rauh SP, Meijer JS, Busch KJG, Numans ME, et al. Experiences with tailoring of primary diabetes care in well-organised general practices: a mixed-methods study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1218.

Van der Wees PJ, Friedberg MW, Guzman EA, Ayanian JZ, Rodriguez HP. Comparing the implementation of team approaches for improving diabetes care in community health centers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):608.

von Meyenfeldt EM, van Nassau F, de Betue CTI, Barberio L, Schreurs WH, Marres GMH, et al. Implementing an enhanced recovery after thoracic surgery programme in the Netherlands: a qualitative study investigating facilitators and barriers for implementation. BMJ Open. 2022;12(1):e051513.

Wakefield BJ, Lampman MA, Paez MB, Stewart GL. Care management and care coordination within a patient-centered medical home. J Nurs Admin. 2020;50(11):565–70.

Wiener-Ogilvie S, Huby G, Pinnock H, Gillies J, Sheikh A. Practice organisational characteristics can impact on compliance with the BTS/SIGN asthma guideline: Qualitative comparative case study in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9(1):32.

Errida A, Lotfi B. The determinants of organizational change management success: Literature review and case study. International Journal of Engineering Business Management. 2021;1(13):18479790211016270.

Phillips J, Klein JD. Change management: From theory to practice. TechTrends. 2023;67(1):189–97.

Rousseau DM, ten Have S. Evidence-based change management. Organ Dyn. 2022;51(3):100899.

Goodwin GF, Blacksmith N, Coats MR. The science of teams in the military: Contributions from over 60 years of research. Am Psychol. 2018;73(4):322–33.

DiazGranados D, Woods JJ, Wilder A, Curtis MT. Team dynamics in the air: A review of team research relevant to aviation. Human factors in aviation and aerospace. 2023. p. 199–215.

Salas E, Tannenbaum SI, Kozlowski SWJ, Miller CA, Mathieu JE, Vessey WB. Teams in space exploration: A new frontier for the science of team effectiveness. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2015;24(3):200–7.

Hackman JR. From causes to conditions in group research. J Organ Behav. 2012;33(3):428–44.

Tannenbaum SI, Salas E. Teams that work: The seven drivers of team effectiveness. Illustrated. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2020. p. 272.

Tuckman BW. Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychol Bull. 1965;63:384–99.

Salas E, Stagl KC, Burke CS. 25 years of team effectiveness in organizations: Research themes and emerging needs. In: International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology 2004. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 2004; p. 47–91. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.1002/0470013311.ch2 Cited 2022 May 16

Proctor EK, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76.

Lengnick-Hall R, Williams NJ, Ehrhart MG, Willging CE, Bunger AC, Beidas RS, et al. Eight characteristics of rigorous multilevel implementation research: a step-by-step guide. Implement Sci. 2023;18(1):52.

Wensing M, Sales A, Aarons GA, Xu D (Roman), Wilson P. Evidence for objects of implementation in healthcare: considerations for Implementation Science and Implementation Science Communications. Implementation Sci. 2022;17(1):83.

Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Widerquist MAO, Lowery J. The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implement Sci. 2022;17(1):75.

Shortell SM, Marsteller JA, Lin M, Pearson ML, Wu SY, Mendel P, et al. The role of perceived team effectiveness in improving chronic illness care. Med Care. 2004;42(11):1040–8.

Yakovchenko V, Morgan TR, Chinman MJ, Powell BJ, Gonzalez R, Park A, et al. Mapping the road to elimination: a 5-year evaluation of implementation strategies associated with hepatitis C treatment in the veterans health administration. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1348.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Ikzzui Chu, Jamie Feldman, Grace Kinkler, Rachael Park, and Jaely Wright for their assistance with article screening.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health grants MH123729 (EAM), MH124914 (DJK), and MH126231 (GAA), the National Cancer Institute U01CA275118 (GAA), National Institute on Drug Abuse R01DA049891 (GAA), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant R18HS026862 (CBW), and the Collaboration and Conflict Research Lab at Carnegie Mellon University Tepper School of Business. The content of this manuscript does not represent the views of funding agencies and is solely the responsibility of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EAM conceptualized and developed the protocol for this review, participated in article screening, data extraction, quality appraisal, and analysis, and led manuscript development and writing. DJK, GAA, LRW, ES, and CBW provided guidance and input into the protocol and methods and interpretation of results. AS participated in article screening, data extraction, and preparation of supplementary files. MLK developed the search strategy and conducted database searches. MAD participated in quality appraisal. DJK, GAA, LRW, ES, and CBW reviewed multiple drafts of the manuscript and provided critical input and editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

GAA is a Co-Editor-in-Chief of Implementation Science and on the Editorial Board of Implementation Science Communications; all decisions on this paper were made by another editor. The authors declare that they have no other competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

McGuier, E.A., Kolko, D.J., Aarons, G.A. et al. Teamwork and implementation of innovations in healthcare and human service settings: a systematic review. Implementation Sci 19, 49 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-024-01381-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-024-01381-9