Abstract

Background

Many Indigenous communities across the USA and Canada experience a disproportionate burden of health disparities. Effective programs and interventions are essential to build protective skills for different age groups to improve health outcomes. Understanding the relevant barriers and facilitators to the successful dissemination, implementation, and retention of evidence-based interventions and/or evidence-informed programs in Indigenous communities can help guide their dissemination.

Purpose

To identify common barriers to dissemination and implementation (D&I) and effective mitigating frameworks and strategies used to successfully disseminate and implement evidence-based interventions and/or evidence-informed programs in American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN), Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (NH/PI), and Canadian Indigenous communities.

Methods

A scoping review, informed by the York methodology, comprised five steps: (1) identification of the research questions; (2) searching for relevant studies; (3) selection of studies relevant to the research questions; (4) data charting; and (5) collation, summarization, and reporting of results. The established D&I SISTER strategy taxonomy provided criteria for categorizing reported strategies.

Results

Candidate studies that met inclusion/exclusion criteria were extracted from PubMed (n = 19), Embase (n = 18), and Scopus (n = 1). Seventeen studies were excluded following full review resulting in 21 included studies. The most frequently cited category of barriers was “Social Determinants of Health in Communities.” Forty-three percent of barriers were categorized in this community/society-policy level of the SEM and most studies (n = 12, 57%) cited this category. Sixteen studies (76%) used a D&I framework or model (mainly CBPR) to disseminate and implement health promotion evidence-based programs in Indigenous communities. Most highly ranked strategies (80%) corresponded with those previously identified as “important” and “feasible” for D&I The most commonly reported SISTER strategy was “Build partnerships (i.e., coalitions) to support implementation” (86%).

Conclusion

D&I frameworks and strategies are increasingly cited as informing the adoption, implementation, and sustainability of evidence-based programs within Indigenous communities. This study contributes towards identifying barriers and effective D&I frameworks and strategies critical to improving reach and sustainability of evidence-based programs in Indigenous communities.

Registration number

N/A (scoping review)

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Many Indigenous communities across the USA and Canada experience a disproportionate burden of health disparities [1,2,3]. These disparities exist across populations, age ranges, public health domains, disease prevention, and management contexts. For example, American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (NH/PI) youth, in particular, have experienced higher prevalence of sexual and reproductive health and chronic disease disparities [1,2,3]. In 2017, AI/AN females (15-19 years) had the highest teen birth rate (32.9 per 1000) compared to other racial/ethnic groups (18.8 per 1000) nationally [3]. Further, compared to white peers, AI/AN and NH/PI youth exhibit higher prevalence of obesity (76.7% vs. 63.2%), diabetes (21.4% vs. 8%), and mental health conditions (including a 3-fold greater suicide rate) [4]. Similarly, prevalence of diabetes in Canadian First Nations and Inuit communities is 2.5 to 5 times greater than the general population [5], and First Nations communities experience higher rates of cancer due to limited access to preventive services [2, 6, 7]. In response, Indigenous communities have partnered with researchers to design and evaluate culturally relevant health programs. This work has increased the availability of a number of evidence-based interventions (EBIs) suitable for implementation in Indigenous communities [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32].

Evidence-based interventions (EBI) refer to treatments that have been evaluated for a degree of effectiveness in changing target behavior through outcome evaluations [33, 34]. They are validated for a specific purpose when applied to a specific population and thus are only useful for a range of health and social problems that underly its design [34]. Changing parts of the EBI will invalidate it by impacting its integrity and effectiveness [34]. Validation of EBIs occurs through large group research or a series of small group studies [33, 34]. However, there might be cases where the intervention was not effective when applied to a specific case [34]. The use of mainstream “evidence-based practices” (EBP), in place of culturally relevant programs, has been a subject of concern in Indigenous communities—where the use of EBP are mandated by Federal or State funding—conflicting with tribal values or ways of knowing [35,36,37,38,39]. Evidence-based public health practices involve the development, implementation, and evaluation of effective programs and policies in public health through the utilization of principles of scientific reasoning to combine individual clinical expertise with the most prominent scientific evidence [40, 41]. It draws on principles of good practice and integrates sound professional judgments with a systematic body of research [42]. Emergent practices, including practice-based evidence and cultural adaptation can improve the compatibility of EBPs in AI/AN communities [33]. Indigenous tribes and researchers have advocated for the inclusion of traditional practices in evidence-based programs [35, 36, 43], and Tribal Best Practices (TBP) have bridged that divide, incorporating both cultural-based evidence and testable outcomes [33].

The design of culturally relevant EBPs in Indigenous communities ranges from surface to deeper level adaptations [37]. Few mainstream EBPs have been rigorously evaluated with AI/AN populations, which in turn generates limited outcomes or impacts for this group [44,45,46]. Some EBPs may be better aligned with tribal usability and acceptability than others [46]. There exists a need to further explore EBIs, EBPs, and evidence-informed programs (EIPs) in the context of Indigenous populations [33, 43, 46, 47]. Evidence-informed programs (EIPs), a sub-category of EBIs, are of particular interest—as they aim to integrate research evidence, alongside practitioner expertise, as well as community members’ experience with the practice—such as elders, adults, children, community-health workers, and tribal leaders [48,49,50].

The emergence of EBPs, cultural adaptations, and their associated evidence base increases the importance of understanding the most salient barriers and facilitators to the successful adoption, implementation, dissemination, and sustainability of EBIs in Indigenous communities. Several contextual factors can assist or hinder this process and may be further confounded by the geographic, cultural, and political diversity of Indigenous communities [9]. These factors can occur at each level of the socio-ecological model (SEM) [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Individual (intrapersonal) factors include characteristics, attitudes, and skills of program staff to implement and evaluate programs. Interpersonal factors include influencing roles of family members, peers, and mentors and their training skills. Organizational factors include administrative support, cultural components, and management of resources within Indigenous organizations (e.g., staff turnover and training, participant recruitment and retention, technology availability and use, program funding). Community factors are embedded within the physical and social environment (e.g., integration with cultural values, transportation). Public policy factors include social and cultural norms supporting certain behavioral outcomes, along with health, educational, economic, and social policies that exacerbate social inequalities between subgroups in Indigenous communities [11]. The requirements and demands of implementing EBIs are often mismatched with the capacities of the Indigenous communities that need them, undermining broad EBI scale-up and dissemination [51]. Increased reach and implementation of EBIs can be facilitated by the use of guiding dissemination and implementation (D&I) frameworks, theories, and models, referred hereto as models [52, 53] and by the application of empirically validated strategies [54, 55]; yet few studies have examined their application in guiding the implementation of EBIs within Indigenous communities [8, 10]

Dissemination and implementation models

The formalization of research in D&I is growing and numerous models exist to guide this process [52, 53]. Research-to-practice models are most frequently applied and are intended for use by diverse stakeholders (e.g., researchers, community-based practitioners, and funders) to systematically guide and critically assess prevention efforts [56, 57]. They also help to inform on specific D&I steps, such as community needs assessment, to identify important barriers and facilitators, and inclusion of community members’ expert knowledge in implementation planning, and assessment of community capacity [56]. The “Dissemination and Implementation Models in Health Research and Practice Webtool,” a collaboratively developed decision support tool, provides an updated database of D&I frameworks to assist researchers and practitioners to generate research questions, select, adapt, and combine D&I models for particular study contexts, and implement and evaluate D&I models [53]. Despite the utility of D&I models and availability of decision tools, their application to guide program implementation has been the exception rather than the rule [8, 9, 58, 59].

Implementation strategies

These are practical tasks (often associated with D&I models) recommended to aid the successful D&I of research findings into clinical and community practice [60]. Taxonomies of strategies to successfully facilitate the adoption, use, and maintenance of EBIs include the ERIC (Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change) and SISTER (School Implementation Strategies, Translating ERIC Resources) taxonomies [54, 55]. The ERIC taxonomy comprises 73 strategies devoted to implementation of EBIs in healthcare settings [54, 60]. The SISTER strategies are an adaptation from those in ERIC but focused on, and more compatible with, school and community-based contexts [61]. The SISTER taxonomy comprises nine domains: (1) use evaluative and iterative strategies; (2) provide interactive assistance; (3) adapt and tailor to context; (4) develop stakeholder interrelationships; (5) train and educate stakeholders; (6) support educators; (7) engage consumers; (8) use financial strategies; and (9) change infrastructure [59, 60]. Within the nine domains are 75 strategies focused on training, local technical assistance, adoption, high fidelity implementation of EBIs, and program replication in school-based settings [62, 63]. Additional previously identified strategies, seminal to use in Indigenous communities, include integration of EBIs within the cultural context [64, 65], involvement of Indigenous leaders, and ensuring sufficient resources (i.e., economic, health, and political) [9, 64, 65].

The purpose of this scoping review was to identify common barriers and effective mitigating D&I models and strategies to successfully disseminate and implement evidence-based programs in American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN), Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (NH/PI), and Canadian Indigenous communities. This review builds on a published multi-case study by Jernigan et al. (2020) to develop culturally tailored D&I strategies to enhance the ability of researchers to scale up effective interventions among Indigenous communities [8]. This scoping review may further contribute to informing and guiding future D&I initiatives aimed at reducing health disparities in this population.

Methods

The review team comprised researchers with expertise in D&I and in the development and implementation of EBIs for Indigenous communities in the US and Canada. The PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) was used as a reference checklist in the development of the study sections [66]. Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) York methodology guided the review [67]. This framework methodology comprises five steps to (1) identify research questions; (2) search for relevant studies; (3) select studies relevant to the research questions; (4) chart the data; and (5) collate, summarize, and report results. The method ensures transparency, enables replication of the search strategy, and increases the reliability of study findings [67].

Step 1. Identify research questions

Three guiding research questions for the scoping review were: (1) What are the main barriers encountered in the D&I of programs and EBIs in Indigenous communities?; (2) Which research-to-practice models have been used to promote the D&I of health promotion EBIs in Indigenous communities?; (3) What implementation strategies have been used in Indigenous communities for program and EBI adoption, implementation and/or maintenance?

Step 2. Search for relevant studies

Keywords and mesh terms were developed in corroboration with a research librarian experienced with scoping review protocols. Search terms focused on AI/AN and NH/PI communities, Native communities, Indigenous tribes, tribal groups, dissemination models, dissemination frameworks, implementation frameworks, EBIs, and US and Canadian territories (Table 1). Educational subject headings and Boolean operators were adopted as search tools to narrow, widen, and combine literature searches. The Rayyan platform was used to condense all studies generated from our search [68]. Three electronic databases (PubMed, EMBASE, and Medline (Ovid)), selected for their breadth and focus on psychosocial and behavioral science, were searched to identify peer-reviewed literature from primary data sources, secondary data sources, and case reports. The review of the literature databases was completed over a period of 2 months, ending in June 2020. Articles were screened for eligibility by reviewer pairs (CM and BH; RS and MP) over a period of 3 months, ending in September 2020.

Inclusion criteria

Included were peer-reviewed studies, published in English between 2000 and 2020 that (1) described the use of D&I models and frameworks to increase the dissemination, implementation, or maintenance of evidence-based or evidence-informed programs among Indigenous communities, and (2) were conducted among AI/AN, NH/PI, and Indigenous populations of any age range located in the USA or Canada. ‘Dissemination’ and ‘Implementation’ were defined in accordance with the 2016 National Institute of Health definitions [69]. Indigenous populations of interest included individuals identifying as AI/AN, NH/PI, or Indigenous in the USA and Canada. EBIs were defined as any evidence-based or evidence-informed intervention or program disseminated or implemented in AI/AN, NH/PI, and/or Canadian Indigenous communities to improve health and behavioral outcomes. The rigor of evidence supporting the dissemination, implementation, or maintenance of these programs was not a criterion by which articles were included or excluded. Articles that describe the D&I of either evidence-based or evidence-informed programs were included.

Exclusion criteria

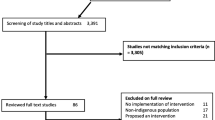

Excluded were studies that addressed populations distinct from Indigenous communities or targeted samples that did not exclusively identify as Indigenous communities located in the USA or Canada, studies focusing solely on improved behavioral or health outcomes with no reference to the D&I field, and studies that only reported general recruitment strategies, follow-up studies after the implementation of a program, or that focused solely on ethical issues related to the implementation of these programs. Initial screening and Rayyan page construction were performed by the lead author (LS). Reviewer pairs (CM and BH; RS and MP) conducted secondary screening of the titles and abstracts. Disagreements were resolved by reaching consensus through discussions that involved the initial reviewer (LS) (Fig. 1).

Step 3. Selection of studies relevant to the research questions

The lead author (LS) extracted and summarized the data from relevant studies. Reviewer pairs (CM and BH; RS and MP) reviewed the data extraction and summary tables for accuracy. Conflicting opinions were resolved by consensus discussion. Summary tables included an evidence table describing each study’s parameters including guiding D&I models, identified barriers, and mitigating strategies. D&I models were identified using the ‘Dissemination and Implementation Models in Health Research and Practice Webtool’ previously described [53]. Barriers, contextual factors that hinder implementation at each level of the socio-ecological model (SEM) [11], were classified by the 5 levels of the (SEM) and by barrier categories based on major themes within the broader SEM framework. The SEM framework acts as a comprehensive external reference to the D&I models and strategies; therefore, it aids in the assessment of such models and strategies when applied to multiple and interacting determinants of health behaviors [11].

D&I strategies were categorized and coded according to the SISTER framework (previously described). The SISTER taxonomy was used as the referent due to its utility for school and community-based contexts [61]. Initial categorization and coding by the lead author (LS) was compared to independent categorization with reviewer pairs for inter-rater reliability in a subsample of 38% (n = 8) studies. Inter-rater reliability was conducted in two rounds with discrepancies resolved by consensus discussion. Resulting inter-rater reliability was 90% for strategy-level matching and 70% for domain-level matching (Supplemental Tables 1 & 2).

Steps 4 and 5. Data charting and collation, summarization, and reporting of results

Study characteristics were tabulated for primary author, country, study type, sample size, target population, study topic area, and D&I model (Table 2). Identified barriers were tabulated by SEM level and classified to one of nine barrier categories (Personnel Challenges & High Turnover; Distrust; Funding; Lack of Integration with Cultural Values; Social Determinants of Health in Communities (physical, mental, health, social, and financial challenges); Insufficient Evaluation Skills; Technology Barriers; Limited Retention and High Attrition; Climate Conditions) (Table 3). The specific strategies were rank ordered within the SISTER domains, as well as based on importance and feasibility (Table 4).

Results

The initial study extraction resulted in 79,585 studies from PubMed (n = 87), EMBASE (n = 79,485), and Medline Ovid (n = 13) (Fig. 1). Studies were excluded due to targeting non-Native communities (n = 89), implementing medical protocols and treatments (n = 79,398), taking place outside the USA or Canada (n = 17), or failing to address dissemination or implementation processes (strategies, theories, or frameworks) related to evidence-based or evidence-informed programs among Indigenous communities (n = 21). Duplicate studies were deleted (n = 16). Thirty-eight studies met inclusion criteria from PubMed (n = 19), EMBASE (n = 18), and Medline (n = 1). An additional 17 studies were excluded following a full study review due to failure to 1) report D&I strategies (n = 2), 2) correspond to definitions of D&I (n = 8), or 3) focus on D&I (n = 7). A total of 21 eligible studies were retained for analysis.

The 21 retained studies were published between 2004 and 2020 (Table 2). Most studies (14/21, 66%) were published in 2015 or later (n = 14), and most were conducted in the USA (14/21, 66%). Study designs included qualitative studies (n = 3); case studies (n = 7); randomized controlled trials (n = 3); pilot studies (n = 2); cross-sectional studies (n = 2); quasi-experimental studies (n = 3); and systematic review (n = 1) Study implementation duration varied from 5-hour trainings to projects of 13 months duration. For quasi-experimental studies and randomized controlled trials, study follow-up periods ranged from 0 months (assessment directly after program completion) to 3 years. The evidence-based programs described in the studies were community-based programs carried out in diverse tribal settings.

Priority populations and key stakeholders

Priority populations who were actively involved (or targeted) in implementation activities were adults (81%, n = 17) and/or children/youth (43%, n = 9) (Table 2). Adult participants included tribal members and elders (AI/AN, n = 4; NH, n = 1; First Nation, n = 1), community health workers (n = 1), women (AI/AN, n = 1; Choctaw, n = 1), mothers and caregivers (AI/AN, n = 1; First Nation, n = 1, Choctaw, n = 1); and those with chronic disease and health challenges (AI/AN with Alzheimer’s, n = 1; adults enrolled in fetal alcohol spectrum disorder services, n = 1; Indigenous victims of car accidents, n = 1; NH with cardiovascular disease and hypertension, n = 2). Key stakeholders who were crucial to planning program implementation included decision makers in healthcare, school, community, organizations, academics, and government (Table 2).

Content domains

The evidence-based programs targeted a variety of health domains, including chronic disease and injury, substance misuse, wellness and illness prevention, and historical trauma (Table 2). Chronic disease and injury topics included hypertension and cardiovascular disease (n = 3), obesity (n = 1), asthma (n = 1), diabetes (n = 1), hearing loss (n = 1), Alzheimer’s (n = 1), palliative care (n = 1), and motor vehicle crashes (n = 1). Substance misuse included misuse of alcohol and other drugs (n = 5) and tobacco use (n = 1). Wellness and illness prevention topics included maternal and child health (n = 1), sexual health (n = 4), nutrition (n = 4), physical activity (n = 1), improved access to healthcare services (n = 2), breast and cervical cancer screening (n = 1), overall children’s well-being (n = 1), and reduction of environmental contaminants exposures (n = 1). One study focused on a historical approach to health through walking the Trail of Tears and 2 studies reported programs addressing multiple health topics [8, 10, 31].

Tribal communities and settings

Diverse tribal communities were represented in this review, including AI/AN (n = 13), Inuit (n = 2), and First Nation/Indigenous (n = 7), and Native Hawaiian (n = 2) communities (Table 2). AI/AN communities included tribes in Oklahoma, California, Alaska, Arizona, and the Pacific Northwest (Oregon, Idaho, and Washington). Inuit communities included tribes in Greenland and Northern Canada. First Nation/Indigenous and Native Hawaiian communities had representation from multiple regions in Canada and Hawaii respectively. Settings comprised Native nations, reservations and reserves, tribal agencies and associations, health agencies, academic affiliates, and schools (Table 2).

D&I barriers

Eighty-nine barriers to implementation were reported in 17 studies (81%), representing the five levels of the socio-ecological model (SEM): Individual (n = 22), interpersonal (n = 6), organizational (n = 49), community (n = 41), and society/policy (n = 26) (Table 3). Barriers were also sorted into nine categories (Table 3) based on major themes that were established through similarity of barriers highlighted across studies at the different levels of SEM. Some barriers fit into the SEM levels, and thus generated more than one theme. For instance, Barlow et al. (2018) highlighted “socioeconomic, geographic, and structural challenges” as a barrier, affecting the individual, community, and society/policy levels of the SEM. The barrier category themes emerging from this barrier and its subsequent SEM classification included “funding,” “social determinants of health in communities,” and “climate conditions.” Most cited barriers (n = 38) sorted into the Community/Society-Policy category of “Social determinants of health in communities.” A majority of studies also cited “Personnel challenges and high turnover” (n = 29), “Funding” (n = 18); “Lack of integration with cultural values (n = 11), and “Limited retention and high attrition” (n = 9) Other barrier categories included Technology barriers (n = 7); Distrust (n = 6); Insufficient evaluation skills (n = 3); and Climate conditions (n = 2).

D&I models

Sixteen studies (76%) used a specific D&I model to promote the adoption and implementation of health promotion EBIs in Indigenous communities (Table 2). Eight different unique models were cited. Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) was most commonly reported (n = 11). Four studies used models that focused on dissemination and/or implementation (Knowledge-to-Action Framework, Diffusion of Innovation Theory, and RE-AIM), andragogy (Adult Learning Theory), or inductive and culturally responsive processes (Culturally Grounded Models of Health Promotion). Remaining models focused on the broader implementation process inclusive of dissemination. Ten studies used a D&I model for the purpose of identifying barriers and/or facilitators to the dissemination process; seven studies highlighted the main barriers and/or facilitators that were encountered during the implementation process.

Implementation strategies

All SISTER domains were represented, and all extracted D&I strategies were matched to relevant SISTER strategies However, not all SISTER strategies were represented in the included studies. One hundred and eighty-four D&I strategies (n = 184) were identified, corresponding to 60 (80%) of the SISTER strategies. A range of three through nineteen strategies were reported in any one study. The most commonly reported SISTER strategy (identified in 86% of studies) was: “Build partnerships (i.e., coalitions) to support implementation” (#21) (Table 4). Four SISTER strategies, previously recognized as being highly important for D&I success were represented in the top 10 strategies [33]. These were “Conduct ongoing training” (#39), “Monitor the progress of the implementation effort” (#9), “Provide ongoing consultation/coaching” (#44), and “Make training dynamic” (#43). These strategies occur in the domains of “Train and educate stakeholders” and “Use evaluative and iterative strategies.” Four SISTER strategies previously described as most feasible for successful D&I were also represented in the top 10. These were: “Make training dynamic” (#43), “Distribute educational materials” (#42), “Facilitation/Problem solving” (#12), and “Capture and share local knowledge” (#22) (Table 4).

Discussion

The purpose of this scoping review was to identify barriers and mitigating D&I processes related to the adoption and implementation of EBIs in Indigenous communities. Analysis of the 23 included studies (conducted between 2004 and 2020) may contribute to our understanding of common barriers and mitigating D&I models and strategies used to successfully disseminate and implement EBIs in Indigenous communities in the United States, Hawaii, Pacific Islands, and Canada [8, 10, 12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32].

D&I models

The majority of the studies (76%) used a D&I model to guide the dissemination and/or implementation of an EBI. Such studies have increased in recent years with 66% of the included studies published since 2015. This reflects the recognition of D&I to address existing and emerging health disparities and is consistent with a broader increase in D&I research. The most frequently reported model was Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) (n = 11), which encompasses an array of principles consistent with partnering with Indigenous minorities [70]. A recent systematic review by Julian McFarlane et al. (2021) [71] highlighted the large increase in the number of CBPR-related studies targeting a broad racial and ethnic representation in research. More than 85% of these studies saw statistically positive outcomes when applying CBPR methods, particularly community partner participation in study advisory committees, data collection, the development of interventions, and participant recruitment [65].

CBPR aims to (1) recognize the Indigenous community as a unit of identity, (2) build on the community’s strengths and resources, (3) facilitate collaborative partnerships in all phases of the research, (4) integrate local knowledge and actions that benefit all partners, (5) empower community members to address social inequalities, (6) involve a cyclical and iterative process, (7) address health from both positive and ecological perspectives, and (8) disseminate findings and knowledge gained to all partners [72]. These principles represent an important foundation to guide ethical D&I studies and are complementary with common reported strategies (described below). Yet CBPR is not without limitations and may not account for the specific array of facilitation strategies and prescriptive steps associated with many D&I models [70]. The frequency of application of D&I models other than CBPR was relatively low (n = 5). Greater research on D&I models in Indigenous communities may enhance the quality of implementation planning and evaluation in those settings, building empirical evidence for the utility of such models using traditional CBPR approaches [73, 74]. Encouraging these systematic approaches can also expand our knowledge-base on the most salient D&I models and strategies for Indigenous communities [73, 74].

Barriers and mitigating D&I strategies

This study reinforced the critical need to identify and implement D&I strategies at all levels of the socio-ecological model to address common barriers that impede implementation efforts. The social milieu in which programs are deployed in Indigenous communities can be complex and challenging. Principal among these challenges are consideration of social determinants of health, perceptions of community trust, community skill sets, and financial challenges. Social determinants of health are important considerations when attempting to reach underserved populations as they address issues related to the complex mental, health, social, physical, and socioeconomic issues of communities. They can represent major barriers to program implementation. Cited factors that can compromise program implementation in Indigenous communities include poverty, homelessness or residential instability, geographic remoteness with accompanying challenges of access to healthcare service, and greater transportation expenses. Across the literature, intentional information gathering and community involvement were critical to program success. These included “assessing for readiness and identifying barriers and facilitators,” “involving governing organizations,” “informing local opinion leaders,” and “involving students, family members, and other staff” [13,14,15,16,17,18, 23, 24, 26,27,28,29,30,31]. More broadly, the strategy of “changing or altering the environment” was employed where feasible, again in consort with community stakeholders.

Complicating the challenge of social determinants is the perception of trust between community members and healthcare providers, or between program participants and the entity delivering the program (i.e. organization, academic institution, governmental agency). These relate to the barrier categories of “distrust” and “lack of integration with cultural values.” Building partnerships to support implementation was the most commonly cited SISTER strategy across the included studies (86%). However, despite the importance of building partnerships in the community and sharing its local knowledge, additional strategies are indicated. Most studies (55%) reported organizational barriers related to involving the views and experiences of elders, community health workers, families, and youth as part of the implementation process [13, 15, 20,21,22, 28, 30, 32]. Hearing the community voice and attending to community needs can further engender trust. The expertise of Indigenous community members, elders, and health planners, many of whom have unique skills, particularly in the fields of cultural adaptation, tailoring interventions, and appropriate implementation is highly valued and can help to alleviate community concerns [75] as well as smooth logistics involved with navigating the complex tribal internal review and research review boards necessary for collaboration with external academic and research partners [8].

The studies mentioned other D&I strategies that can promote cohesion around program implementation at the organizational level. These included recruiting and retaining families through trust-building; ensuring convenience of program offerings, forming local advisory boards and task forces, creating cultural activities, and using mass media tools (newspaper, written materials, and radio programs) to promote programs. Organizational administration included attention to data management; capacity-building efforts, prioritization of strategies, and collaboration with academic researchers and regional stakeholders [8, 10, 12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Frequently cited was the need to elicit community support through engagement of the community and Native stakeholders in the planning and implementation process [13, 15, 20,21,22, 27, 28, 30, 32]. This is vital to aid in cultural learning, integration of cultural values, and inclusion of indigenous role models to optimize cultural compatibility and the potential for sustained implementation. Native stakeholders should be engaged in the planning phase to ensure that their needs and desires are fulfilled [13, 15, 20,21,22, 28, 30, 32].

Staff training, personalized technical assistance, staff commitment to engage youth, and continuous evaluation of staff performance [8, 10, 12, 17, 23,24,25, 29, 30] are necessary for sustained implementation of programs within Indigenous communities. These strategies can mitigate the “Personnel Challenges and High Turnover” that was cited in 65% of the studies [13,14,15,16, 18, 20,21,22,23, 25, 32]. High turnover rates can undermine personnel skills training due to the continuous loss of acquired talent and the need to accustom new personnel to the community and program material [13,14,15,16, 18, 20,21,22,23, 25, 32]. Insufficient skills needed to deliver the program material were cited as a common barrier. SISTER strategies included under the two domains—“training and educating stakeholders” and “developing stakeholder interrelationships”—could help address those common barriers.

Funding is a continuous challenge affecting sustained implementation. Funding issues were frequently reported by Native stakeholders during interviews and focus group sessions and emerged as a main theme in qualitative studies [13,14,15]. This included a lack of sustained funding at the organizational level to increase research outputs [12,13,14,15,16,17,18, 20, 22, 26]. This in turn led to a limited availability of resources and thus the inability to maintain programs outcomes for longer periods of time. Specific financial barriers included high cost of salaries, housing, transportation, and other mission fees needed to hire social workers, program adopters and implementers, and healthcare workers [13, 14, 20,21,22,23, 25, 32]. Accessing new funding sources was a leading D&I strategy employed in Native communities. Continuous delivery of program resources and material is predicated on sustained financial support without which D&I efforts are hobbled [55].

Studies describing intervention implementation at the policy level cited the importance of creating and implementing new public health policies to overcome societal and economic barriers. These crosscut other socioecological levels and included the high costs of imported goods and healthy foods, inadequate funding allocations to healthcare systems, limited assistance for uninsured clients, limited resources for chronic diseases, improper management of historical oppression and trauma, infrastructure shortcomings, and high levels of poverty [13, 15, 16, 18, 25]. All nine domains encompassing multiple SISTER strategies were mentioned in the studies. Studies on the effectiveness of D&I strategies in this domain are limited [54, 61]. Future work could focus on the multilevel policies that shape social determinants of health and their impact on D&I outcomes in Indigenous settings. Holistic approaches with culturally tailored strategies are essential to overcome potential barriers.

Strengths & limitations

These studies correspond highly to reported SISTER strategies previously categorized as important and feasible in non-indigenous contexts [61]. Four of five strategies rated as most important were among the top ten reported in this review. These strategies included (1) “Monitor the progress of the implementation effort” (#9); (2) “Conduct ongoing training” (#39); (3) “Make training dynamic” (#43); and (4) “Provide ongoing consultation/coaching” (#44). The 5th strategy, “Improve implementers’ buy-in” (#51), was not represented. Four of five strategies rated as most feasible were among the top ten reported in this review. These included (1) “Capture and share local knowledge” (#22), (2) Distribute educational materials” (#42); (3) “Make training dynamic” (#43); and (4) “Facilitation/Problem solving” (#12). The 5th strategy, “Remind school personnel” (#53), was not represented in any of the studies. Financial strategies categorized under the domain “Use financial strategies” received a low feasibility rating in Lyon et al. (2019) and were only reported in a few of our studies [61]. This may reflect the lack of funding that was identified as a barrier in 50% of the studies [61].

Findings need to be interpreted in the context of study limitations. First, despite a comprehensive search of the most relevant psychosocial databases, this review did not include tracing of reference lists in included studies, hand-searches of journals, or grey literature. Broader reviews are recommended that account for these sources. Second, the D&I field is growing rapidly, so it is possible that some relevant studies were not found due to inadvertent omission of search terms. The mesh terms included as many technical D&I keywords as possible and the collaboration of a research librarian who imposed rigor in the protocols likely mitigated this concern. Future reviews are recommended to include emerging terms from this rapidly evolving field. Third, the scope of the current review was limited. Formal assessment of the quality of the included studies was beyond scope and the inter-rater reliability, though acceptable with domain and strategy correspondence of 70% and 90% respectively, was based on assessment of only eight (38%) of the included studies. Fourth, matching the identified D&I strategies to the SISTER strategies was challenging due to the diversity of terms used to describe any given strategy. Consistency of terminology represents a challenge for any emerging field. Standardizing the nomenclature will be important to enable clear research and practice guidelines for EBI implementation. Fifth, the use of SEM to categorize barriers and contextual factors limits comparison to other D&I frameworks such as CFIR (Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research) or EPIS (Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment). However, SEM categorization will inform the selection of multilevel implementation strategies to facilitate EBI uptake in Indigenous communities [52]. It also provides an objective assessment agnostic of any particular D&I framework [52]. Finally, the SISTER strategies were originally developed based on studies in non-Indigenous settings. Although the taxonomy is comprehensive and provides a useful comparison for non-indigenous settings, it may also miss cultural influences or D&I processes that are unique to Indigenous communities. The similarity with findings from Lyon et al. (2019) indicates some validity across cultural settings [61]. Future studies are recommended to provide guidance on which strategies to use to promote behavior and health changes in Indigenous settings. The use of existing accepted taxonomies in this study may provide guidance for future work.

Conclusion

This scoping review describes D&I efforts to translate research and change practice in Indigenous communities across the USA and Canada. Results may contribute to a broader perspective of barriers and mitigating strategies to inform and guide future D&I initiatives in Indigenous communities, with a goal to reduce health disparities in these populations. This study emphasized ranks of barriers and related D&I strategies (matched to the adapted SISTER strategies) that appear salient for Indigenous communities including focusing on culturally relevant partnerships, trainings, evaluations, and adaptation. The existing diversity in culture, beliefs, values, and resources across tribes and borders is a major consideration for future D&I initiatives. Efforts to apply D&I models and strategies are increasing within Native communities as they are in non-indigenous communities. This study can guide researchers and community partners using D&I models and strategies to improve the reach and sustainability of evidence-based programs in Indigenous communities.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

de Ravello L, Everett Jones S, Tulloch S, Taylor M, Doshi S. J Sch Health. 2014;84(1):25–32.

US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. Profile: Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders. Policy and Data; 2020. https://www.minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=65

Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK. Births in the United States, 2017. NCHS Data Brief. 2018;318:1–8.

Adakai M, Sandoval-Rosario M, Xu F, et al. Health disparities among American Indians/Alaska Natives — Arizona, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1314–8. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6747a4.

Pirisi A. Country in Focus: health disparities in Indigenous Canadians. The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology. 2015;3(5):319.

United States Census Bureau. Selected population profile in the United States; 2017. shorturl.at/mpCGQ

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Trends in tuberculosis, 2018. Tuberculosis; 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/statistics/tbtrends.htm

Jernigan VBB, D’Amico EJ, Keawe’aimoku Kaholokula J. Prevention research with indigenous communities to expedite dissemination and implementation efforts. Prev Sci. 2020;21(Suppl 1):74–82.

Jernigan VBB. Community-based participatory research with Native American communities: the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program. Health Promot Pract. 2010;11(6):888–99.

Markham CM, Craig Rushing S, Jessen C, Gorman G, Torres J, Lambert WE, et al. Internet-based delivery of evidence-based health promotion programs among American Indian and Alaska Native youth: A case study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5(4):e225.

Dahlberg LL, Krug EG. Violence-a global public health problem. In: Krug E, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, editors. . Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. p. 1–56.

Craig Rushing S, Stephens D, Shegog R, Torres J, Gorman G, Jessen C, et al. Healthy native youth: improving access to effective, culturally relevant sexual health curricula. Front Public Health. 2018;6:225.

Counil É, Gauthier MJ, Blouin V, Grey M, Angiyou E, Kauki T, et al. Translational research to reduce trans-fat intakes in Northern Québec (Nunavik) Inuit communities: a success story? Int J Circumpolar Health. 2012;71:18833. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v71i0.18833 PMID: 22818719; PMCID: PMC3417698.

Walker SC, Whitener R, Trupin EW, Migliarini N. American Indian perspectives on evidence-based practice implementation: results from a statewide Tribal Mental Health Gathering. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015 Jan;42(1):29–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0530-4 PMID: 24242820.

Orians CE, Erb J, Kenyon KL, Lantz PM, Liebow EB, Joe JR, et al. Public education strategies for delivering breast and cervical cancer screening in American Indian and Alaska Native populations. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2004;10(1):46–53. https://doi.org/10.1097/00124784-200401000-00009 PMID: 15018341.

Barlow A, McDaniel JA, Marfani F, et al. Discovering frugal innovations through delivering early childhood home-visiting interventions in low-resource tribal communities. Infant Ment Health J. 2018;39(3):276–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21711.

Black KJ, Morse B, Tuitt N, Big Crow C, Shangreau C, Kaufman CE. Beyond content: cultural perspectives on using the internet to deliver a sexual health intervention to American Indian youth. J Prim Prev. 2018;39(1):59–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-017-0497-0.

Douglas ML, McGhan SL, Tougas D, et al. Asthma education program for First Nations children: an exemplar of the knowledge-to-action framework. Can Respir J. 2013;20(4):295–300. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/260489.

Gates M, Gates A, Hanning R, Tsuji L. Building community nutrition capacity through participatory research in a remote first nation: lessons learned from Kashechewan. Ontario. Can J Diabetes. 2013;37:S286–7.

Jernigan VBB, Boe G, Noonan C, Carroll L, Buchwald D. Assessing feasibility and readiness to address obesity through policy in American Indian reservations. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2016;9(3):168–80.

Jiang L, Manson SM, Beals J, et al. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program into American Indian and Alaska Native communities: results from the Special Diabetes Program for Indians Diabetes Prevention demonstration project. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(7):2027–34.

Kaufman CE, Keane EM, Shangreau C, Arthur-Asmah R, Morse B, Whitesell NR. Dissemination and uptake of HIV/STD preventive interventions in American Indian and Alaska Native communities: a case study. Ethn Health. 2018 Aug 27;2018:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2018.1514456.

Martindale-Adams J, Tah T, Finke B, LaCounte C, Higgins BJ, Nichols LO. Implementation of the REACH model of dementia caregiver support in American Indian and Alaska Native communities. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(3):427–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-017-0505-1.

Mokuau N, Browne CV, Braun KL, Choy LB. Using a community-based participatory approach to create a resource center for Native Hawaiian elders. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2008;21(3):174.

Moleta CD, Look MA, Trask-Batti MK, Mabellos T, Mau ML. 2016 Writing contest graduate winner: cardiovascular disease training for community health workers serving native Hawaiians and other Pacific peoples. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2017;76(7):190–8 PMID: 28721313; PMCID: PMC5511337.

Nadin S, Crow M, Prince H, Kelley ML. Wiisokotaatiwin: development and evaluation of a community-based palliative care program in Naotkamegwanning First Nation. Rural Remote Health. 2018;18(2):4317. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH4317.

Noe TD, Kaufman CE, Kaufmann LJ, Brooks E, Shore JH. Providing culturally competent services for American Indian and Alaska Native veterans to reduce health care disparities. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(Suppl 4):S548–54. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302140.

Pei J, Carlson E, Tremblay M, Poth C. Exploring the contributions and suitability of relational and community-centered fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) prevention work in First Nation communities. Birth Defects Res. 2019;111(12):835–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdr2.1480.

Rasmus SM, Trickett E, Charles B, John S, Allen J. The qasgiq model as an Indigenous intervention: using the cultural logic of contexts to build protective factors for Alaska Native suicide and alcohol misuse prevention. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2019;25(1):44–54. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000243.

Short MM, Mushquash CJ, Bédard M. Interventions for motor vehicle crashes among Indigenous communities: strategies to inform Canadian initiatives. Can J Public Health. 2014;105(4):e296–305. Published 2014 May 30. https://doi.org/10.17269/cjph.105.4176.

Walters KL, Johnson-Jennings M, Stroud S, et al. Growing from our roots: strategies for developing culturally grounded health promotion interventions in American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian Communities. Prev Sci. 2020;21(Suppl 1):54–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-018-0952-z.

Young NL, Wabano MJ, Anderson MM, Trudeau T, McGavock J, Stacey J. Multiple complexities: perspectives from children’s health and well-being assessment in Canadian Aboriginal communities. In QUALITY OF LIFE RESEARCH 2017 Oct 1 (Vol. 26, No. 1, pp. 109-110). VAN GODEWIJCKSTRAAT 30, 3311 GZ DORDRECHT, NETHERLANDS: SPRINGER.

Walker RD, Bigelow DA. A constructive Indian country response to the evidence-based program mandate. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;43(4):276–81.

What are evidence based interventions (EBI)? [Internet]. Evidence Based Intervention Network. 2011 [cited 2021 Dec 25]. Available from: https://education.missouri.edu/ebi/what-are-evidence-based-interventions-ebi/

Echo-Hawk H. Indigenous communities and evidence building. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;43(4):269–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2011.628920.

Gone JP, Calf Looking PE. American Indian culture as substance abuse treatment: pursuing evidence for a local intervention. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;43(4):291–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2011.628915.

Dionne R, Davis B, Sheeber L, Madrigal L. Initial evaluation of a cultural approach to implementation of evidence-based parenting interventions in American Indian communities. J Community Psychology. 2009;37(7):911–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20336.

Duran B, Harrison M, Shurley M, Foley K, Morris P, DavidsonStroh L, et al. Tribally-driven HIV/AIDS health services partnerships: Evidence-based meets culture-centered interventions. J HIV/AIDS Social Services. 2010;9(2):110–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/15381501003795444.

Morsette A, Van den Pol R, Schuldberg D, Swaney G, Stolle D. Cognitive behavioral treatment for trauma symptoms in American Indian youth: preliminary findings and issues in evidence-based practice and reservation culture. Adv School Mental Health Promotion. 2012;5(1):51–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/1754730X.2012.664865.

Brownson RC, Baker EA, Leet T, Gillespie KN, eds. Evidence-based public health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. Public Health and Information Tutorial. http://phpartners.org/tutorial/04-ebph/2-keyConcepts/4.2.2.html. Accessed 2 Dec 2008.

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Gray JAM, et al. Evidence-based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. Br Med J. 1996;312:71–2.

Green J, Tones K. Towards a secure evidence base for health promotion. J Public Health Med. 1999;21(2):133–9.

Gone JP. A community-based treatment for Native American historical trauma: prospects for evidence-based practice. J Consulting Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(4):751–62.

BigFoot DS. The process and dissemination of cultural adaptations of evidence-based practices for American Indian and Alaska Native children and their families. In: Sarche MC, Spicer P, Farrell P, Fitzgerald HE, editors. American Indian and Alaska Native children and mental health: development, context, prevention, and treatment. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger; 2011a. p. 285–307.

BigFoot DS. The process and dissemination of cultural adaptations of evidence-based practices for American Indian and Alaska Native children and their families. In: Sarche MC, Spicer P, Farrell P, Fitzgerald HE, editors. American Indian and Alaska Native children and mental health: development, context, prevention, and treatment. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger/ABC-CLIO; 2011b. p. 285–307.

BigFoot, D. S., & Funderburk, B. W. Honoring children, making relatives: the cultural translation of parent-child interaction therapy for American Indian and Alaska Native families. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;43(4):309–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2011.628924.

Chaffin M, Bard D, Bigfoot DS, Maher EJ. Is a structured, manualized, evidence based treatment protocol culturally competent and equivalently effective among American Indian parents in child welfare? Child Maltreatment. 2012;17(3):242–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559512457239.

Baillie L, Carrick-Sen D, Marland A, Keil MF. Research and evidence-based practice: The nurse’s role. In: Llahana S, Follin C, Yedinak C, Grossman A, editors. Advanced practice in endocrinology nursing. Cham: Springer; 2019.

Blanchet, K., Allen, C., Breckon, J., Davies, P., Duclos, D., Jansen, J. et al. (2018). Using research evidence in the humanitarian sector: a practice guide. London, UK: Evidence Aid, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and Nesta (Alliance for Useful Evidence).

Boaz A, Davies H, Fraser A, Nutley S, editors. What works now? Evidence-informed policy and practice. Bristol: Policy Press; 2019.

Savaya R, Spiro S, Elran-Barak R. Sustainability of social programs: a comparative case study analysis. Am J Evaluation. 2008;29:478–93.

Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers DA, et al. Bridging research and practice: models for dissemination and implementation research. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(3):337–50.

Dissemination and Implementation Models in Health Research and Practice. Access the D&I Models Webtool. https://dissemination-implementation.org/content/about.aspx#team

Cook CR, Lyon AR, Locke J, Waltz T, Powell BJ. Adapting a compilation of implementation strategies to advance school-based implementation research and practice. Prev Sci. 2019;20(6):914–35.

Lourida I, Abbott RA, Rogers M, Lang IA, Stein K, Kent B, et al. Dissemination and implementation research in dementia care: a systematic scoping review and evidence map. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1) Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0528-y.

Wandersman A, Duffy J, Flaspohler P, Noonan R, Lubell K, Stillman L, et al. Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: the interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3–4):171–81.

Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Science. 2015;10(1):53.

Kaholokula JK, Wilson RE, Townsend CKM, Zhang G, Chen J, Yoshimura S. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program in Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander communities: the PILI ‘Ohana Project. Transl Behav Med. 2014;4:149–59.

Villanueva M, Tonigan JS, Miller WR. Response of Native American clients to three treatment methods for alcohol dependence. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2007;6(2):41–8.

Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013;8:139. Published 2013 Dec 1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-139

Lyon AR, Cook CR, Locke J, Davis C, Powell BJ, Waltz TJ. Importance and feasibility of an adapted set of implementation strategies in schools. J Sch Psychol. 2019;76:66–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2019.07.014.

Boyd MR, Powell BJ, Endicott D, Lewis CC. A method for tracking implementation strategies: an exemplar implementing measurement-based care in community behavioral health clinics. Behav Ther. 2018;49(4):525–37.

Bunger AC, Powell BJ, Robertson HA, MacDowell H, Birken SA, Shea C. Tracking implementation strategies: a description of a practical approach and early findings. Health Res Policy Syst. 2017;15(1):15.

Nasir BF, Hides L, Kisely S, Ranmuthugala G, Nicholson GC, Black E, et al. The need for a culturally-tailored gatekeeper training intervention program in preventing suicide among Indigenous peoples: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):357.

Choi WS, Faseru B, Beebe LA, Greiner AK, Yeh H-W, Shireman TI, et al. Culturally-tailored smoking cessation for American Indians: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2011;12(1):126.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev [Internet]. 2016;5(1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

National Institutes of Health. (2016). Dissemination and implementation research in health. Accessed May 16 from https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-16-238.html

Ritchie SD, Wabano MJ, Beardy J, Curran J, et al. Community-based participatory research with Indigenous communities: the proximity paradox. Health & Place. 2013;24:183–9.

Julian McFarlane S, Occa A, Peng W, Awonuga O, Morgan SE. Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) to enhance participation of racial/ethnic minorities in clinical trials: a 10-year systematic review. Health communication, 1–18. Adv Online Publication. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2021.1943978.

Laveaux D, Christopher S. Contextualizing CBPR: Key principles of CBPR meet the Indigenous research context. Pimatisiwin. 2009;7(1):1.

Chaudoir SR, Dugan AG, Barr CH. Measuring factors affecting implementation of health innovations: a systematic review of structural, organizational, provider, patient, and innovation level measures. Implement Sci. 2013;8:22.

Skolarus TA, Lehmann T, Tabak RG, Harris J, Lecy J, Sales AE. Assessing citation networks for dissemination and implementation research frameworks. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):97. Published 2017 Jul 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0628-2.

Jernigan VBB, Burkhart M, Magdalena C, Sibley C, Yepa K. The implementation of a participatory manuscript development process with Native American tribal awardees as part of the CDC Communities Putting Prevention to Work initiative: challenges and opportunities. Prev Med. 2014;67:51–7.

Acknowledgements

The authors do not have any acknowledgments to declare.

Funding

NIH/NIMHD 1R21MD013960-01A1

Native iCHAMPS: An Innovative Online Decision Support System for Increasing Implementation of Effective Sexual Health Education in Tribal Communities.

PIs: Markham, Shegog, Peskin

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LS was the primary reviewer who carried out the preliminary search, set up the Rayyan platform, extracted the data, and developed the draft of the manuscript. RS and CM were the secondary reviewers who helped out with data collection, analysis, tabulation of information, and manuscript development. MP and BH helped with data analysis and manuscript development. SCR, CJ, and TL provided critical review of drafts of the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not Applicable

Consent for publication

Not Applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sacca, L., Shegog, R., Hernandez, B. et al. Barriers, frameworks, and mitigating strategies influencing the dissemination and implementation of health promotion interventions in indigenous communities: a scoping review. Implementation Sci 17, 18 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-022-01190-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-022-01190-y