Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has challenged health systems worldwide since 2020. At the frontline of the pandemic, healthcare workers are at high risk of exposure. Compliance with infection prevention and control (IPC) should be encouraged at the frontline. This systematic review aimed to assess the effects of dissemination interventions to improve healthcare workers’ adherence with IPC guidelines for respiratory infectious diseases in the workplace.

Methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, and the Cochrane COVID-19 Study Register. We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cluster RCTs that assessed the effect of any dissemination strategy in any healthcare settings. Certainty of evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach. We synthesized data using random-effects model meta-analysis in Stata 14.2.

Results

We identified 14 RCTs conducted from 2004 to 2020 with over 65,370 healthcare workers. Adherence to IPC guidelines was assessed by influenza vaccination uptake, hand hygiene compliance, and knowledge on IPC. The most assessed intervention was educational material in combined strategies (plus educational meetings, local opinion leaders, audit and feedback, reminders, tailored interventions, monitoring the performance of the delivery of health care, educational games, and/or patient-mediated interventions). Combined dissemination strategies compared to usual routine improve vaccination uptake (risk ratio [RR] 1.59, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.54 to 1.81, moderate-certainty evidence), and may improve hand hygiene compliance (RR 1.70; 95% CI 1.03 to 2.83, moderate-certainty). When compared to single strategies, combined dissemination strategies probably had no effect on vaccination uptake (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.07, low-certainty), and hand hygiene compliance (RR 1.16, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.36, low-certainty). Knowledge of healthcare workers on IPC improved when combined dissemination strategies were compared with usual activities, and the effect was uncertain in comparison to single strategy (very low-certainty evidence).

Conclusions

Combined dissemination strategies increased workers’ vaccination uptake, hand hygiene compliance, and knowledge on IPC in comparison to usual activities. The effect was negligible when compared to single dissemination strategies. The adoption of dissemination strategies in a planned and targeted way for healthcare workers may increase adherence to IPC guidelines and thus prevent dissemination of infectious disease in the workplace.

Trial registration

Protocol available at http://osf.io/aqxnp.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), continues to spread globally since the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Knowledge about transmission, signs and symptoms, and prognostic factors has evolved rapidly and improved decision-making for this global threat [6]. Governments have implemented different non-pharmacological strategies to control person-to-person transmission, such as use of masks, quarantine, and social distancing, which has led to control of the spread [3, 7]. A combination of these strategies seems to be key for their success, which continues to be dynamic with emerging variants, changes in policies, and disease waves—within and across countries—, which increases the disease burden [8]. At the same time, an unprecedented global effort has also enabled the development of high-efficacy vaccines [9].

At the frontline of the pandemic, healthcare workers are considered at high risk of exposure [10]. Several factors increase this risk, such as prolonged exposure to large numbers of infected and asymptomatic people, inadequate personal protection due to shortage of personal protective equipment or respirator reuse and extended use policies, and insufficient training for infection prevention and control (IPC) [11]. In China, 4% of COVID-19 cases were in healthcare workers [12], accounting for 30% of total hospitalizations related to COVID-19 in Wuhan during January 2020 [13]. By the end of the first quarter of 2020, COVID-19 infections were estimated to be between 10 and 20% among healthcare workers in Italy [12].

Since the healthcare setting seems to play an important role in the spread of the disease [14], achieving high compliance with IPC measures requires changes in behavior and changes in the workplace. There are still gaps in the processes of translating the best evidence into practice. In this context, it is important to know which implementation strategies based on dissemination interventions are the most effective to improve healthcare workers’ adherence to IPC recommendations [15,16,17].

Health-related information dissemination is primarily focused on communicating research results, targeting and tailoring the findings and messages to an appropriate audience (‘help to make it happen’) [18, 19]. Dissemination also involves an active and personalized process, a necessary step for knowledge adoption and implementation in the field of public health or clinical practice [20].

Implementation strategies designed for healthcare workers include a number of different interventions. Such interventions involve various components to be delivered through a variety of modalities and in different contexts. Due to the vast set of interventions aiming to disseminate guidelines or recommendations in health services, the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care (EPOC) taxonomy [21] is a practical way to identify implementation strategies targeted at workers and designed to improve adherence to IPC guidelines. Implementation strategies are targeted at healthcare organizations and mainly include audit and feedback, patient or provider education, reminders, mentoring, etc. [21].

Implementation strategies related to dissemination must be fostered in health services to support behavior changes of healthcare professionals in the workplace aiming at increasing adherence to guidelines for IPC [17]. These strategies can improve the delivery, practice, and organization of healthcare services in different scenarios [22, 23].

Behavior change of healthcare providers may require complex approaches and several factors could influence adherence to IPC guidelines when managing respiratory diseases, for instance, factors related to the message itself and the way of disseminating it, factors related to organizational culture, and other contextual factors [17, 23, 24]. These and other factors should be considered when deciding to implement different dissemination strategies in healthcare settings [25, 26].

In this scenario, we reviewed the current literature to assess the effects of dissemination interventions to improve healthcare workers’ adherence to IPC guidelines for respiratory infectious diseases in the workplace.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted following the Cochrane handbook for methods [27] and the reporting adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) 2020 statement [28]. A previous protocol was developed and published in the Open Science Framework repository (http://osf.io/aqxnp).

Searches

We searched Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2020, Issue 9) in the Cochrane Library (searched on 23 September 2020); MEDLINE (via Ovid; 1946 to 23 September 2020); Embase (via Ovid; 1974 to 23 September 2020); and Cochrane COVID-19 Study Register (February 2020 to 23 September 2020; http://covid-19.cochrane.org). We screened the references of related Cochrane systematic reviews and the list of references of the included studies.

An information specialist conducted our search of the literature, which was revised by a content expert. Complete information on the search strategies is available in the protocol. We limited the searches to randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and no other limits were applied. Search outputs were imported into Covidence platform (www.covidence.org) to remove duplicates and perform further review steps.

Selection process

The team of review authors (MTS, TFG, EC, ENS, JOMB) in pairs and independently screened titles and abstracts at Covidence platform. After screening the first 100 studies, the team met to assess disagreements and adjust the selection process. We resolved disagreements by consensus. The same process was applied to select studies in full text that were considered eligible based on title and abstract screening.

Study quality assessment

We used the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for RCT version 1 [29], integrated with Covidence [30], to assess the included studies (dual; second reviewer checks all judgements). We judged the risk of bias as “low,” “high,” or “unclear” and provided support for judgement of the following items: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias. We adopted “unclear risk” only in cases of lack of information about the methods.

Data extraction strategy

All authors extracted data from the studies (MTS, TFG, EC, ENS, JOMB) using a customized form in Covidence, which were cross-checked by a second author (MTS, TFG).

We collected characteristics of the studies (author, year of research, country, setting, study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, sponsorship source, conflicts of interest), characteristics of the study participants, description of the interventions, and results.

Data synthesis and presentation

We sought data for adherence to IPC guidelines in each intervention group assessed in the studies according to the nature of the data. We grouped the outcomes of similar enough studies according to the intervention and longest available follow-up. For vaccine uptake, we collected the number of healthcare workers vaccinated and the total number of personnel assessed in each group. Hand hygiene compliance data relied on the number of hand hygiene actions by all hand hygiene opportunities (before patient contact, before aseptic task, after body fluid exposure, after patient contact, after contact with patient surroundings). Knowledge about IPC data was based on the number of individuals assessed and measured for knowledge in each group (mean and standard deviation of the test score or score improvement and interquartile range).

We calculated the mean differences (MD) for knowledge on IPC and risk ratios (RR) of vaccination uptake and hand hygiene compliance outcomes along with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Outcome effect of each intervention was assessed in comparison to usual activities or other strategies. As studies’ interventions relied on multiple dissemination interventions, effects were presented separately into “combined strategies vs. usual activities” and “combined strategies vs. single strategies.” We adopted random-effects meta-analysis for all outcomes [27], considering the outcomes as related but slightly divergent intervention effects. For the cluster RCTs included, we calculated the design effect using the intracluster correlation coefficient, the number of clusters and the average sample size of each cluster. We calculated the RR by entering the sample size and the number of results adjusted by the design effect [29]. We used Stata (version 14.2) to calculate all meta-analyses. When meta-analysis was not feasible, we synthesized the results narratively. We assessed the presence of heterogeneity by inspecting forest plots and calculated the I2 statistic and Chi2 test. In visually discrepant results in the forest plots distribution, we considered as substantial heterogeneity results with significant Chi2 test (p < 010) and I2 statistic > 50% [27].

Evidence of effectiveness

We judged available outcomes (vaccination uptake, hand hygiene compliance, and knowledge) using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to assess the certainty of the evidence in its five domains: limitations, indirectness, imprecision, inconsistency, and other factors [31]). We rated the certainty of the evidence of each outcome as “very low,” “low,” “moderate,” or “high” and prepared evidence profiles and summary of findings tables of the effects of combined strategies in comparison to the controls (usual activities or single strategies).

Results

Review statistics

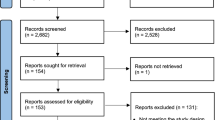

Out of 6941 retrieved records and 2 additional records identified through other sources, we screened 5698 unique records after duplicate removal based on title and abstracts. We assessed full text of 38 studies and included 14 studies [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45] in this systematic review and meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

We excluded 15 full-text studies. Five had an ineligible population [46,47,48,49,50], four had an ineligible intervention [51,52,53,54], three had an ineligible study design [55,56,57], two had ineligible outcomes [58, 59], one occurred in offices and thus had an ineligible setting [60]. Nine studies were ongoing up to the conclusion of this review [61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69], of which four started in 2020 [64,65,66,67]. Two trials were registered in 2007 and 2009 and remained “ongoing” in their protocols [68, 69]. All of them assessed combined dissemination strategies to improve IPC for healthcare workers, including education, training, audit and feedback, positive deviance, a voice enabled virtual assistant (Amazon Alexa device), gamification, and evidence-based telehealth [61,62,63,64,65,66,67].

Study characteristics

We included seven parallel RCTs and seven cluster-RCTs, conducted from 2004 to 2020 and funded mainly with research sponsorship (Table 1). Over 65,370 healthcare workers of all categories were assessed for infection prevention and control adherence outcomes that included influenza vaccination uptake, hand hygiene compliance, and knowledge on infection prevention and control. Two studies did not state the number of healthcare workers assessed, just the number of opportunities for hand hygiene [37, 44].

Figure 2 displays the interventions assessed by included studies. All studies based their dissemination of implementation strategies on educational interventions, including materials, meetings, and games [32,33,34,35, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45, 70]. Six studies that assessed hand hygiene compliance [33, 37, 40, 42, 44, 70] used adapted versions of the WHO multimodal hand hygiene improvement strategy, which includes provision of products and infrastructure for hand hygiene, education, observation and feedback, reminders in the workplace, and creation of a safety culture. Three studies [38, 39, 44] conducted surveys and focus group sessions to tailor their dissemination interventions. Monitoring the performance of the delivery of healthcare was employed in two [33, 44], and audit and feedback in four studies [33, 37, 42, 44]. Patient-mediated interventions were used in one of the experimental groups in one study [44], and public release of performance data was part of the intervention in another [39].

Most studies were held in hospitals [34, 37,38,39, 41,42,43,44,45], three in nursing homes [32, 33, 40], one in primary healthcare center [70], and one in a reference clinic for chronic diseases [35]. Nine studies took place in Europe, three in Asia, and two in America (Table 1).

Study quality assessment

The main biases of the studies were lack of blinding of participants, personnel, and outcomes assessors (Fig. 3). Sequence generation, allocation concealment, and incomplete outcome data affected over one quarter of studies. No study was free from risk of bias (Fig. 3).

Nine studies used adequate methods for random sequence generation [32, 33, 37, 38, 41,42,43,44,45] and were at low risk of selection bias. Four did not describe the randomization method and were classified as unclear [34, 39, 40, 70]. One study [35] relied on an alphabetical list of the workers, leading to high risk of bias in randomization.

Nine included studies adequately concealed the allocation [32, 33, 37, 38, 41,42,43,44,45], two were not clear about this process [34, 70], and three did not conceal the allocation [35, 39, 40], regarded as high risk of selection bias.

Three studies adequately blinded participants and personnel and were at low risk of bias [33, 35, 45]. It was not possible to blind participants and the personnel to their group due to the nature of interventions in 11 studies classified as high risk of performance bias [32, 34, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44, 70]. Nine studies did not blind their outcomes assessors to the intervention and we rated as high risk of detection bias [33, 34, 37,38,39,40, 43, 44, 70]. Five RCTs blinded the outcomes assessors, considered as low risk of detection bias [32, 35, 41, 42, 45].

Four studies were at high risk of attrition bias [32, 39, 45, 70] due to losses of facilities or participants during follow up. The other 10 studies had no problem regarding incomplete data; thus, we considered them to be at low risk of attrition bias [33,34,35, 37, 38, 40, 41, 43, 44]. We assessed all studies as having a low risk of reporting bias, since they reported the outcomes as described in their protocol or methods.

Vaccination uptake

Combined dissemination strategies improved the influenza vaccination uptake compared to usual activities (RR 1.59, 95% CI 1.54 to 1.81; 4 studies [32, 35, 38, 39], 53,913 participants; I2 = 0%; moderate-certainty evidence; Fig. 4). We downgraded the certainty of evidence by one level for study limitations (Table 2).

Combined dissemination strategies may have little effect or no effect on influenza vaccination uptake, compared to a single dissemination strategy (RR 1.01; 95% CI 0.95 to 1.07; 2 studies [41, 43]; 8340 participants; I2 = 0%; low-certainty evidence; Fig. 4). We downgraded the certainty of evidence by two levels for limitations and imprecision (Table 2).

Hand hygiene compliance

Combined dissemination strategies compared to usual activities improved healthcare workers’ hand hygiene compliance (RR 1.70; 95% CI 1.03 to 2.83; 4 studies [33, 37, 40, 70]; 2134 hand hygiene opportunities; I2 = 92.2%; moderate-certainty evidence; Fig. 5). We downgraded the certainty of evidence by one level for study limitations (Table 2). As directions of studies’ effects were similar, serious heterogeneity was disregarded. We did not find any factor (year, design, settings, participants, sample size, intervention, or funding) among these studies that explained the statistical heterogeneity.

Combined dissemination strategies may have little effect or no effect on hand hygiene compliance, compared to a single dissemination strategy (RR 1.16; 95% CI 0.99 to 1.36; 2 studies [42, 71]; 3358 hand hygiene opportunities; I2 = 85%; low-certainty evidence; Fig. 5). Homogeneity in the directions of studies’ effects led us to disregard serious inconsistency. We downgraded the certainty of evidence by two levels due to study limitations and imprecision (Table 2).

Knowledge

One study assessed whether educational materials and meetings compared to usual activities would improve knowledge about preventive behaviors against healthcare-associated infections in hospital nurses [34]. The researchers assessed knowledge in the pre-intervention, post-intervention and 4 months later, using a questionnaire with a scale ranging from 0 (insufficient knowledge) to 10 (adequate knowledge). These combined dissemination strategies improved healthcare workers’ knowledge of preventive behaviors on IPC, compared with usual activities (MD 4.10; 95% CI 3.39 to 4.81 in post-intervention; MD 4.1; 95% CI 3.36 to 4.84 in 4 months later; 120 participants; very low-certainty evidence). Due to very low certainty evidence—downgraded by three levels for study limitations, indirectness, and imprecision—, we are uncertain of this effect (Table 2).

One study assessed whether the educational game plus the pre-hospital COVID-19 guidelines compared to the guideline alone would improve knowledge about the use of protective equipment [45]. The researchers measured knowledge using an online survey about the choice of personal protective equipment in short clinical scenarios on a scale of percentage of correct answers (0 to 100%). We are uncertain if combined dissemination strategies impact on healthcare workers’ knowledge of use of protective equipment, compared to a single strategy (17% IQR 8, 33% versus 8% IQR 8, 33%; p = 0.27; 173 participants; very low-certainty evidence). We downgraded the certainty of evidence by three levels for study limitations, indirectness, and imprecision (Table 2).

Discussion

Combined strategies compared to usual activities improved the influenza vaccination uptake (moderate-certainty evidence), hand hygiene compliance (low-certainty evidence), and knowledge (very low-certainty evidence). When compared to single strategies, combined interventions did not improve vaccination uptake (low-certainty evidence), hand hygiene compliance (low-certainty evidence), and knowledge (very low-certainty evidence).

This systematic review covered a diverse set of drivers that could improve the IPC practices for respiratory infectious diseases in healthcare workers, such as vaccination, hand hygiene, and knowledge about infection prevention, but we did not find any RCT that focused especially on the implementation of IPC guidelines. In addition, we have not provided subgroup analyses and equity considerations of the assessed dissemination interventions because the studies have not stratified their results by gender, age groups, or healthcare workers’ categories.

Despite digital media have wide availability, few studies employed strategies for dissemination using electronic means. Healthcare workers, including those who have worked in the pandemic, are familiar with electronic tools [72]. Strategies that use this type of dissemination could be leveraged to improve the compliance with protocols and guidelines for IPC among healthcare workers, and many challenges have already been recognized [73]. Digital competence may vary depending on the setting and low and middle-income countries' contexts, which may require specific approaches to address gaps to apply these strategies [74].

Analyses by professional category were not feasible also considering that the included studies covered a wide range of healthcare workers, such as doctors, nurses, therapists, assistants, among others, assessed in settings from primary to tertiary care. The included studies assessed dissemination strategies in settings with hospitalizations and long-term care units, with intense contact with patients that raises the risk of spread of infection.

Compared to no intervention, combined dissemination strategies increased the uptake of vaccination, hand hygiene compliance, and knowledge about infection prevention. While combined strategies showed to be effective, it is unclear whether they would be superior to single intervention strategies. To maintain the best balance in the dissemination strategy, decision-makers should monitor the impact along with the implementation and consider equity issues, in order to include considerations about, for example, the different pre-existing socioeconomic and cultural conditions that influence disparities related to risks and health outcomes in the pandemic. The improvement of combined intervention when compared to no intervention and its low effect when compared to a single intervention were also observed by studies that focused on strategies to support the dissemination of guidelines [75,76,77].

We hypothesize that a single dissemination strategy can potentially improve healthcare workers’ adherence to good practices to prevent infections and may be a good starting point to change behavior. Despite superior results of combined strategies in comparison to single ones in present review, advantages of single interventions, when compared to multifaceted interventions, have been previously observed [24]. In a pandemic, rapid and specific changes would potentially bring positive results with less use of resources and stressful workload. Future research should evaluate these single interventions compared to usual care in order to confirm the effectiveness of these interventions, which would have lower cost and better viability.

Workers may feel insecure when local guidelines are long, unclear, or do not correspond to national or international guidelines [17]. The level of support received interferes with healthcare workers’ responses to follow IPC guidelines, as some strategies can lead to a greater workload. Clear communication about the guidelines and proper training are also essential for improvement. Altogether, these factors can influence whether healthcare workers follow the guidelines or not [17]. Effective dissemination strategies are thus central to strengthening the process of implementing IPC guidelines, and should be prioritized by decision-makers, especially in low-resource settings [78].

Conclusions

Compared to no intervention, combined dissemination strategies increased healthcare workers’ vaccination uptake, hand hygiene compliance, and knowledge about infection prevention. When compared to single dissemination strategies, the effect was modest or null. Further research should focus on assessing the effectiveness of single interventions compared to usual practices. The results seem to be favorable to the use of educational strategies combined with other non-educational dissemination strategies, such as audit and feedback. Dissemination strategies may increase adherence to IPC guidelines for healthcare workers management of respiratory diseases and thus prevent their dissemination in the workplace.

Availability of data and materials

The data and materials supporting the conclusions of this article are available at http://osf.io/aqxnp.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- EPOC:

-

Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care

- GRADE:

-

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- IPC:

-

Infection prevention and control

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- MD:

-

Mean differences

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- RR:

-

Risk ratio

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

References

Lurie N, Saville M, Hatchett R, Halton J. Developing Covid-19 vaccines at pandemic speed. N Engl J Med. 2020.

Mahase E. Covid-19: WHO declares pandemic because of “alarming levels” of spread, severity, and inaction. BMJ. 2020;368:m1036.

Park M, Cook AR, Lim JT, Sun Y, Dickens BL. A systematic review of COVID-19 epidemiology based on current evidence. J Clin Med. 2020;9(4).

Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, Cutrell JB. Pharmacologic treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. 2020.

Wilder-Smith A, Chiew CJ, Lee VJ. Can we contain the COVID-19 outbreak with the same measures as for SARS? Lancet Infect Dis. 2020.

Wilder-Smith A, Freedman DO. Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. J Travel Med. 2020;27(2).

Paho: Ongoing living update of potential COVID-19 therapeutics: summary of rapid systematic reviews. Rapid review. In: Institutional Repository for Information Sharing - IRIS/PAHO.

Castro MC, Kim S, Barberia L, Ribeiro AF, Gurzenda S, Ribeiro KB, et al. Spatiotemporal pattern of COVID-19 spread in Brazil. Science. 2021.

Bhatta M, Nandi S, Dutta S, Saha MK. Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2): a systematic review for potential vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021:1–18.

Adams JG, Walls RM. Supporting the health care workforce during the COVID-19 global epidemic. JAMA. 2020.

Wang J, Zhou M, Liu F. Reasons for healthcare workers becoming infected with novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China. J Hosp Infect. 2020.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Risk assessment on COVID-19, 23 April 2020 [https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/current-risk-assessment-novel-coronavirus-situation].

Verbeek JH, Rajamaki B, Ijaz S, Sauni R, Toomey E, Blackwood B, et al. Personal protective equipment for preventing highly infectious diseases due to exposure to contaminated body fluids in healthcare staff. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;4:Cd011621.

Del Rio C, Malani PN. COVID-19-new insights on a rapidly changing epidemic. JAMA. 2020.

Shah N, Castro-Sanchez E, Charani E, Drumright LN, Holmes AH. Towards changing healthcare workers’ behaviour: a qualitative study exploring non-compliance through appraisals of infection prevention and control practices. J Hosp Infect. 2015;90(2):126–34.

Lai X, Wang X, Yang Q, Xu X, Tang Y, Liu C, et al. Will healthcare workers improve infection prevention and control behaviors as COVID-19 risk emerges and increases, in China? Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020;9(1):83.

Houghton C, Meskell P, Delaney H, Smalle M, Glenton C, Booth A, et al. Barriers and facilitators to health care workers’ compliance with Infection Prevention and Control recommendations for respiratory infectious diseases: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020.

Lomas J. Diffusion, dissemination, and implementation: who should do what? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;703:226–35 discussion 235-227.

Graham ID, Tetroe JM. Getting evidence into policy and practice: perspective of a health research funder. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;18(1):46–50.

Vernooij RW, Willson M, Gagliardi AR. Characterizing patient-oriented tools that could be packaged with guidelines to promote self-management and guideline adoption: a meta-review. Implement Sci. 2016;11:52.

Effective Practice Organisation of Care. EPOC taxonomy [https://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-taxonomy]

Presseau J, Ivers NM, Newham JJ, Knittle K, Danko KJ, Grimshaw JM. Using a behaviour change techniques taxonomy to identify active ingredients within trials of implementation interventions for diabetes care. Implement Sci. 2015;10:55.

Chauhan BF, Jeyaraman MM, Mann AS, Lys J, Skidmore B, Sibley KM, et al. Behavior change interventions and policies influencing primary healthcare professionals’ practice-an overview of reviews. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):3–3.

Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R, Mowatt G, Fraser C, Bero L, et al. Changing provider behavior: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Med Care. 2001;39(8 Suppl 2):II2–45.

Pantoja T, Opiyo N, Lewin S, Paulsen E, Ciapponi A, Wiysonge CS, et al. Implementation strategies for health systems in low-income countries: an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(9).

Chapman E, Haby MM, Toma TS, de Bortoli MC, Illanes E, Oliveros MJ, et al. Knowledge translation strategies for dissemination with a focus on healthcare recipients: an overview of systematic reviews. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):14.

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.2 (updated February 2021). Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook: Cochrane; 2021.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

Higgins J, Green S: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. In.: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011.

Covidence systematic review software. In. Melbourne: Veritas Health Innovation; 2020.

Schünemann HJ, Guyatt G, Brożek J, Oxman AD: GRADE handbook. Handbook for grading the quality of evidence and strength of recommendation using the GRADE approach. In.: The GRADE Working Group; 2013.

Borgey F, Henry L, Lebeltel J, Lescure P, Le Coutour X, Vabret A, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention campaign on influenza vaccination of professionals in nursing homes: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Vaccine. 2019;37(10):1260–5.

Ho ML, Seto WH, Wong LC, Wong TY. Effectiveness of multifaceted hand hygiene interventions in long-term care facilities in Hong Kong: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(8):761–7.

Jeihooni AK, Kashfi SH, Bahmandost M, Afzali Harsini P. Promoting preventive behaviors of nosocomial infections in nurses: the effect of an educational program based on health belief model. Investig Educ Enferm. 2018;36(1):e09.

Lehmann BA, Chapman GB, Franssen FM, Kok G, Ruiter RA. Changing the default to promote influenza vaccination among health care workers. Vaccine. 2016;34(11):1389–92.

Martín-Madrazo C, Soto-Díaz S, Cañada-Dorado A, Salinero-Fort MA, Medina-Fernández M, Carrillo de Santa Pau E, et al. Cluster randomized trial to evaluate the effect of a multimodal hand hygiene improvement strategy in primary care. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(7):681–8.

Mertz D, Dafoe N, Walter SD, Brazil K, Loeb M. Effect of a multifaceted intervention on adherence to hand hygiene among healthcare workers: a cluster-randomized trial. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(11):1170–6.

Riphagen-Dalhuisen J, Burgerhof J, Frijstein G, van der Geest-Blankert A, Danhof-Pont M, De Jager H, et al. Hospital-based cluster randomised controlled trial to assess effects of a multi-faceted programme on influenza vaccine coverage among hospital healthcare workers and nosocomial influenza in the Netherlands, 2009 to 2011. Eurosurveillance. 2013;18(26):20512.

Rothan-Tondeur M, Filali-Zegzouti Y, Golmard J-L, De Wazieres B, Piette F, Carrat F, et al. Randomised active programs on healthcareworkers’ flu vaccination in geriatric health care settings in France: The VESTA study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15(2):126–32.

Yeung WK, Tam WS, Wong TW. Clustered randomized controlled trial of a hand hygiene intervention involving pocket-sized containers of alcohol-based hand rub for the control of infections in long-term care facilities. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(1):67–76.

Doratotaj S, Macknin ML, Worley S. A novel approach to improve influenza vaccination rates among health care professionals: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36(4):301–3.

Huis A, Schoonhoven L, Grol R, Donders R, Hulscher M, van Achterberg T. Impact of a team and leaders-directed strategy to improve nurses’ adherence to hand hygiene guidelines: a cluster randomised trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(4):464–74.

Schmidtke KA, Nightingale PG, Reeves K, Gallier S, Vlaev I, Watson SI, et al. Randomised controlled trial of a theory-based intervention to prompt front-line staff to take up the seasonal influenza vaccine. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29(3):189–97.

Stewardson AJ, Sax H, Gayet-Ageron A, Touveneau S, Longtin Y, Zingg W, et al. Enhanced performance feedback and patient participation to improve hand hygiene compliance of health-care workers in the setting of established multimodal promotion: a single-centre, cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(12):1345–55.

Suppan L, Abbas M, Stuby L, Cottet P, Larribau R, Golay E, et al. Effect of an e-learning module on personal protective equipment proficiency among prehospital personnel: web-based randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e21265.

Arbogast JW, Moore-Schiltz L, Jarvis WR, Harpster-Hagen A, Hughes J, Parker A. Impact of a comprehensive workplace hand hygiene program on employer health care insurance claims and costs, absenteeism, and employee perceptions and practices. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58(6):e231.

Chami K, Gavazzi G, Bar-Hen A, Carrat F, de Wazières B, Lejeune B, et al. A short-term, multicomponent infection control program in nursing homes: a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(6):569.e569–17.

Christensen L, Rasmussen CS, Benfield T, Franc JM. A randomized trial of instructor-led training versus video lesson in training health care providers in proper donning and doffing of personal protective equipment. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020;14(4):514–20.

Ong MS, Magrabi F, Post J, Morris S, Westbrook J, Wobcke W, et al. Communication interventions to improve adherence to infection control precautions: a randomised crossover trial. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:72.

Temime L, Cohen N, Ait-Bouziad K, Denormandie P, Dab W, Hocine MN. Impact of a multicomponent hand hygiene–related intervention on the infectious risk in nursing homes: a cluster randomized trial. Am J Infect Control. 2018;46(2):173–9.

Bessesen MT, Radonovich L, Rattigan SM, Cummings D, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Simberkoff M, Gibert CL, Nyquist A-C, Price CS, Gorse G: 1205. Healthcare personnel knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs towards infection prevention and control measures for protection from respiratory infections. In: Open Forum Infectious Diseases: 2019: Oxford University Press US; 2019: S433-S433.

Chughtai AA, Seale H, Dung TC, Hayen A, Rahman B, Raina MacIntyre C. Compliance with the use of medical and cloth masks among healthcare workers in Vietnam. Ann Occup Hyg. 2016;60(5):619–30.

Radonovich LJ, Bessesen MT, Cummings DA, Eagan A, Gaydos C, Gibert C, et al. The Respiratory Protection Effectiveness Clinical Trial (ResPECT): a cluster-randomized comparison of respirator and medical mask effectiveness against respiratory infections in healthcare personnel. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):1–10.

Zamora JE, Murdoch J, Simchison B, Day AG. Contamination: a comparison of 2 personal protective systems. CMAJ. 2006;175(3):249–54.

Fuller C, Michie S, Savage J, McAteer J, Besser S, Charlett A, et al. The Feedback Intervention Trial (FIT)–improving hand-hygiene compliance in UK healthcare workers: a stepped wedge cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e41617.

Marra AR, D’Arco C, de Arruda Bravim B, Martino MDV, Correa L, Silva CV, et al. Controlled trial measuring the effect of a feedback intervention on hand hygiene compliance in a step-down unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(8):730–5.

Suppan M, Gartner B, Golay E, Stuby L, White M, Cottet P, et al. Teaching adequate prehospital use of personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic: development of a gamified e-learning module. JMIR Serious Games. 2020;8(2):e20173.

Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Mae R, Vincent L, Peladeau N, Beduz MA, et al. Computer-assisted resilience training to prepare healthcare workers for pandemic influenza: a randomized trial of the optimal dose of training. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:72.

McConeghy KW, Baier R, McGrath KP, Baer CJ, Mor V. Implementing a pilot trial of an infection control program in nursing homes: results of a matched cluster randomized trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(8):707–12.

Savolainen-Kopra C, Haapakoski J, Peltola PA, Ziegler T, Korpela T, Anttila P, Amiryousefi A, Huovinen P, Huvinen M, Noronen H. STOPFLU: is it possible to reduce the number of days off in office work by improved hand-hygiene? Trials. 2010;11(1):1–9.

A randomized controlled study to test the effects of education on nurses’ wearing of personal protective equipment [https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central/doi/10.1002/central/CN-01969524/full]

Evaluation of an enhanced tuberculosis infection control intervention in healthcare facilities in Vietnam and Thailand [https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT02073240]

Trial of positive deviance in inpatient wards to reduce hospital infections [https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT02244905]

Liao Y, Wang L, Luo T, Wu S, Wu Z, Chen J, et al. Brief mindfulness-based intervention of ‘STOP (Stop, Take a Breath, Observe, Proceed) touching your face’: a study protocol of a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):e041364.

Innovative Tool to Limit Spread of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID 19) in residential aged care facilities [https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04377165]

Virtual Assistant for COVID-19 PPE [https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT04435275]

COVID-19 Project ECHO in Nursing Homes [https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT04499391]

Actrn: Efficacy of face masks against H1N1 swine influenza. http://www.who.int/trialsearch/Trial2aspx?TrialID=ACTRN12609000778280 2009.

Actrn: A randomised, controlled trial of mask use in control of respiratory virus transmission in Health Care Workers. http://www.who.int/trialsearch/Trial2aspx?TrialID=ACTRN12607000314426 2007.

Martín-Madrazo C, Soto-Díaz S, Salinero-Fort MA, Medina-Fernández M, de Santa Pau EC, Gómez-Campelo P, et al. Cluster randomized trial to evaluate the effect of a multimodal hand hygiene improvement strategy in primary care. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(7):681–8.

Stewardson AJ, Sax H, Gayet-Ageron A, Touveneau S, Longtin Y, Zingg W, et al. Enhanced performance feedback and patient participation to improve hand hygiene compliance of health-care workers in the setting of established multimodal promotion: a single-centre, cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(12):1345–55.

Konttila J, Siira H, Kyngäs H, Lahtinen M, Elo S, Kääriäinen M, et al. Healthcare professionals’ competence in digitalisation: a systematic review. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(5-6):745–61.

Odendaal WA, Anstey Watkins J, Leon N, Goudge J, Griffiths F, Tomlinson M, et al. Health workers’ perceptions and experiences of using mHealth technologies to deliver primary healthcare services: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;3(3):CD011942.

Shiferaw KB, Tilahun BC, Endehabtu BF. Healthcare providers’ digital competency: a cross-sectional survey in a low-income country setting. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1021.

Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay CR, Vale L, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8(6):3–4 1-72.

Tomasone JR, Kauffeldt KD, Chaudhary R, Brouwers MC. Effectiveness of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies on health care professionals’ behaviour and patient outcomes in the cancer care context: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):41.

Squires JE, Sullivan K, Eccles MP, Worswick J, Grimshaw JM. Are multifaceted interventions more effective than single-component interventions in changing health-care professionals’ behaviours? An overview of systematic reviews. Implement Sci. 2014;9:152.

Pantoja T, Opiyo N, Lewin S, Paulsen E, Ciapponi A, Wiysonge CS, et al. Implementation strategies for health systems in low-income countries: an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9(9):CD011086.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Luke Wolfenden and Andy Anglemyer (Cochrane Public Health Review group), Simon Lewin (Cochrane EPOC group), and Robin Featherstone (Cochrane Editorial and Methods Department) for the very useful review and suggestions for the protocol of this systematic review. We also thank Paul Miller (Cochrane EPOC group) and Michelle Haby (University of Sonora) for their valuable contribution to improving the search strategy for this systematic review.

Funding

This project has not been funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MTS, TFG, EC, ENS, and JOMB designed the work, collected and interpreted the data for the work, drafted, and revised it critically. MTS and TFG analyzed the data. All authors approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Silva, M.T., Galvao, T.F., Chapman, E. et al. Dissemination interventions to improve healthcare workers’ adherence with infection prevention and control guidelines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Implementation Sci 16, 92 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-021-01164-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-021-01164-6