Abstract

Background

There is a plethora of interventions and policies aimed at changing practice habits of primary healthcare professionals, but it is unclear which are the most appropriate, sustainable, and effective. We aimed to evaluate the evidence on behavior change interventions and policies directed at healthcare professionals working in primary healthcare centers.

Methods

Study design: overview of reviews.

Data source: MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), The Cochrane Library (Wiley), CINAHL (EbscoHost), and grey literature (January 2005 to July 2015).

Study selection: two reviewers independently, and in duplicate, identified systematic reviews, overviews of reviews, scoping reviews, rapid reviews, and relevant health technology reports published in full-text in the English language.

Data extraction and synthesis: two reviewers extracted data pertaining to the types of reviews, study designs, number of studies, demographics of the professionals enrolled, interventions, outcomes, and authors’ conclusions for the included studies. We evaluated the methodological quality of the included studies using the AMSTAR scale. For the comparative evaluation, we classified interventions according to the behavior change wheel (Michie et al.).

Results

Of 2771 citations retrieved, we included 138 reviews representing 3502 individual studies. The majority of systematic reviews (91%) investigated behavior and practice changes among family physicians. Interactive and multifaceted continuous medical education programs, training with audit and feedback, and clinical decision support systems were found to be beneficial in improving knowledge, optimizing screening rate and prescriptions, enhancing patient outcomes, and reducing adverse events. Collaborative team-based policies involving primarily family physicians, nurses, and pharmacists were found to be most effective. Available evidence on environmental restructuring and modeling was found to be effective in improving collaboration and adherence to treatment guidelines. Limited evidence on nurse-led care approaches were found to be as effective as general practitioners in patient satisfaction in settings like asthma, cardiovascular, and diabetes clinics, although this needs further evaluation. Evidence does not support the use of financial incentives to family physicians, especially for long-term behavior change.

Conclusions

Behavior change interventions including education, training, and enablement in the context of collaborative team-based approaches are effective to change practice of primary healthcare professionals. Environmental restructuring approaches including nurse-led care and modeling need further evaluation. Financial incentives to family physicians do not influence long-term practice change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Approximately one in six Canadians aged 20 years or older suffer from chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, chronic respiratory diseases, arthritis, osteoporosis, mental illness, and cancer [1]. Combining direct medical costs ($38.9 billion) and indirect productivity losses ($54.4 billion), the total economic burden of chronic illness exceeds Canadian $93 billion a year [2]. Despite this enormous expenditure, 12 to 15% of Canadians feel they receive inadequate chronic disease care [3, 4]. The major unmet needs include long waiting periods for medical services [5] and unavailability of essential services [4]. Compared with people in other developed nations, Canadians today are less satisfied with their access to and quality of care [6] and have worse health outcomes for several medical conditions [7]. The numbers of patients with chronic diseases and the existing gap in quality of care present a significant challenge for public health policy-makers [8, 9].

With the objective of closing gaps in quality of care and managing patients with chronic diseases, the implementation of patient-centred treatment has recently gained attention from policy-makers [10–12]. Patient-centered medical centres may become the future backbone of the Canadian healthcare system [13]. These teams may include family physicians, physician assistants, nurses, pharmacists, social workers, mental health counselors/psychologists, dieticians, and midwives among others. To achieve efficient and effective patient-centered medical homes, some changes in the way healthcare is delivered will be required. To do so, effective behavior change interventions and supporting policies are required [14, 15]. However, it is unclear which intervention(s) and policies are appropriate, sustainable, and sufficiently safe to support practice change and improve patient-relevant outcomes in primary healthcare settings. Despite extensive published literature including randomized controlled trials [16, 17], observational studies [18, 19], and systematic reviews [20–22], no recent comprehensive review classifying or evaluating the feasibility or effectiveness of interventions and policies in terms of patients’ and professionals’ outcomes exists. The objectives of this overview of reviews were to identify, classify, and critically appraise reviews evaluating behavior change interventions and policies influencing primary healthcare professionals working at primary healthcare centers.

Methods

Data sources and searches

The search strategy was developed and tested through an iterative process by an experienced medical information specialist in consultation with the review team. We searched MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), CINAHL (EbscoHost), and the Cochrane Library (Wiley). Strategies utilized a combination of controlled vocabulary (e.g., “Physicians", "Primary Care”, “Physician’s Practice Patterns”, “Quality Improvement”) and keywords (e.g., family practitioner, home clinic, policy adherence). Vocabulary and syntax were adjusted across databases. Results were restricted to the English language and the dates from January 2005 to July 2015 (Additional file 1). We used DistillerSR (Version 2, Evidence Partners Inc. ON, Canada) for study selection, data extraction, and project management.

Study selection

We included (1) systematic reviews, overview of reviews, scoping reviews, rapid reviews, or health technology assessments that (2) evaluated behavior change interventions or policies on primary healthcare professionals (including general practitioners/family physicians, physician assistants, nurses, pharmacists, social workers, mental health counselors/psychologists, dieticians, and midwives) (3) working at primary healthcare settings (4) reporting any outcomes of primary healthcare professionals’ practice change, and (5) published in the English language as full-text articles. Primary healthcare settings were defined as the provision of integrated, accessible health care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community [23, 24]. Considering the application of outcomes in the Canadian context, reviews that exclusively included studies conducted in either underdeveloped or developing countries were excluded.

The abstracts and titles of relevant citations were independently screened by two reviewers to determine eligibility. The same two reviewers independently assessed the eligibility of full-text reports of relevant citations using a standardized pre-piloted form outlining the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or with the involvement of a third reviewer, if needed.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two reviewers independently abstracted data from the included reviews using standardized piloted forms. The following data were extracted from each included review: review type, number and study designs that the review included, types of professionals evaluated, interventions, outcomes, therapeutic domains, and authors’ conclusions.

All behavior change interventions and policies were classified into nine categories of interventions and seven categories of policies following the behavior change wheel framework proposed by Michie et al. [15]. This framework consists of a behavior system at the hub, encircled by nine intervention functions and then by seven policy categories. The nine behavior change interventions include (1) education (increasing knowledge or understanding): e.g., continuous medical education; (2) persuasion (using communication to induce positive or negative feelings or stimulate action): e.g., reminders; (3) incentivization (creating expectation of reward): e.g., payment for performance; (4) coercion (creating expectation of punishment or cost): e.g., punishment or fines; (5) training (imparting skills): e.g., communication skills training; (6) restriction (using rules to reduce the opportunity to engage in the target behavior): e.g., rules for prohibiting the use; (7) environmental restructuring (changing the physical or social context): e.g., shared decision-making; (8) modeling (providing an example for people to aspire to or imitate): e.g., local opinion leaders; (9) enablement (increasing means/reducing barriers to increase capability or opportunity): e.g., clinical decision support systems. While the seven policies include: (1) communication/marketing (using print, electronic, telephonic or broadcast media): e.g., advertising media; (2) guidelines (creating documents that recommend or mandate practice): e.g., management guidelines; (3) fiscal (using the tax system to reduce or increase the financial cost): e.g., financial provisions from policy-makers; (4) regulation (establishing rules or principles of behavior or practice): e.g., rules and regulations; (5) legislation (making or changing laws): e.g., law amendments; (6) environmental/social planning (designing and/or controlling the physical or social environment): e.g., social support; (7) service provision (delivering a service): e.g., service or facilitation.

Two reviewers independently, and in duplicate, evaluated the methodological quality of the included reviews using the assessing the methodological quality of systematic reviews (AMSTAR) scoring system [25]. Conflicts were resolved by consensus or discussion with a third reviewer, if needed. Reviews with AMSTAR score ≥8, 4 to 7, ≤3 were considered as high, moderate, or low-methodological quality, respectively.

We summarized the findings that emerged from the subjective judgment matrix, which was based on the authors’ conclusions, qualitative data, quantitative data with statistically significant group differences in terms of patients’ and primary healthcare providers’ outcomes, and the methodological quality of included reviews [25–28]. The protocol for this overview of reviews has been developed prior to conduct the review and provided to the Primary Health Care Branch, Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living, Government of Manitoba, Canada. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for reporting the systematic review were followed.

Results

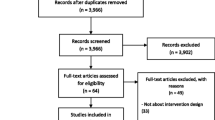

We screened 2771 citations and included 138 reviews representing 3502 individual studies (Fig. 1). The characteristics of the included reviews are presented in Table 1. Of the included studies, three were overviews of reviews [29–31]. Most reviews (91%) investigated behavior change interventions and policies among family physicians primarily managing chronic diseases at primary healthcare centers. We classified the included reviews into eight of nine categories of behavior change interventions including education (n = 28, 20%), enablement (n = 16, 12%), environmental restructuring (n = 18, 13%), incentivization (n = 7, 5%), modeling (n = 2, 2%), multiple interventions (n = 42, 30%), persuasion (n = 4, 3%), training (n = 11, 8%), and three of seven categories of policies including service provision (n = 5, 4%), communications (n = 3, 2%), and guidelines (n = 2, 2%). Major chronic diseases evaluated were mental disorders (n = 12, 9%), diabetes (n = 10, 7%), respiratory diseases (n = 8, 6%), cancer (n = 5, 4%), cardiovascular diseases (n = 4, 3%), arthritis/osteoporosis (n = 3, 2%), and hypertension (n = 2, 2%); some reviews reported more than one chronic disease. Total of 36 (26%) reviews exclusively included randomized controlled trials. The remaining reviews included systematic reviews, observational studies, interrupted time series studies, and controlled before-after studies (Table 1). Of the total included reviews, 68 (49%) reviews were of high quality, 60 (44%) reviews were of moderate quality, and 11 (8%) reviews were of low quality (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Behavior change interventions (Additional file 1: Table S1)

Education (increasing knowledge/understanding)

Twenty-eight reviews [20, 21, 29, 32–56] (n = 509 studies) evaluated educational interventions. Evidence from moderate- to high-quality reviews demonstrated that education to improve knowledge and skills [37–42, 48, 49, 51–56], continuing medical education [20, 21, 29, 34, 43], and academic detailing [32] were found to be effective in professional development to increase knowledge, optimize prescriptions, screening rate, and improve patient outcomes [20, 29, 32–36, 41, 44, 45, 50, 54]. Certain education interventions were evaluated as components of multifaceted education interventions, including interactive educational methods, reminder systems, audit and feedback, academic detailing, computer-based learning, lecture, as well as pamphlet in several reviews [29, 33, 36, 43, 44, 49]; which reported improvement in implementing guidelines into general practice [29], improved antibiotic prescribing [33], improved detection of cancer, dementia, and skin lesions [36, 44, 49]. Conflicting evidence exists on patient feedback. One review [50], based on ten studies, reported some evidence for the effectiveness of using feedback from real patients to improve knowledge and primary healthcare professionals’ practice change exists while other reviews [34, 46, 47] failed to reach the same conclusion.

Enablement (increasing means/reducing barriers to increase capability or opportunity)

Sixteen reviews [57–72] (n = 377 studies) evaluated the use of information technologies including interactive analysis systems [57–59, 69], clinical decision support systems [60, 62–66], electronic health records and prescriptions [61, 68, 72], and point of care testing [67, 70, 71] to increase capability and facilitate practice change of primary healthcare professionals. Evidence from moderate- to high-quality reviews demonstrated that enablement interventions improved communication between healthcare professionals and patients [59, 63], augmented knowledge [61], facilitated the appropriate antibiotic prescriptions [60], increased quality of service, reduced potential adverse events (drug interactions, contraindications, dose monitoring, and adjustment) [62], and improved several patient outcomes [64].

Environmental restructuring (changing the physical or social context)

Nineteen [73–91] (n = 470 studies) evaluated the impact of environmental restructuring including the use of collaborative or shared care practices or the institution of specialized nurses or other allied healthcare professionals [73, 74, 77–83, 85–91], or guideline implementation [75, 76] in primary healthcare settings. Evidence from poor- to high-quality reviews indicate organizational changes to increase collaboration among pharmacists, nurses, prevention coordinators, and other primary healthcare professionals led to increased physicians’ adherence to guidelines [75]. Nurse-led care was found to be as equally effective as general practitioners in patient satisfaction, asthma, cardiovascular, and diabetes management. However, weak study designs and restricted interventional scopes mean that further evaluation is required [80–82, 84], especially in the context of other chronic diseases.

Incentivization (creating an expectation of reward)

Seven reviews [30, 92–97] (n = 198 studies) evaluated the impact of financial incentives on family physicians. All reviews [30, 92–97] of poor- to high-quality failed to provide supportive evidence of any significant improvement in family physicians’ behavior change. One high-quality review [96] observed modest improvements in quality of care for chronic diseases, albeit, the impact on costs, professional behavior, and patient experience remained uncertain.

Modeling (providing an example for people to aspire or imitate)

Two reviews [98, 99] (n = 60 studies) evaluated modeling using local opinion leaders [98], or mental health workers [99] in primary healthcare settings. Evidence from moderate- to high-quality reviews demonstrated that involving local opinion leaders or subject experts to promote evidence-informed practices decreased the rates of consultations and prescriptions [98, 99].

Persuasion (using communication to induce positive or negative feelings or stimulate action)

Four reviews [100–103] (n = 218 studies) reported on interventions categorized as persuasion. Evidence from moderate- to high-quality reviews indicates that reminders [100–103] worked well to reduce unnecessary imaging for lower back pain [100] while improving the rate of screening [101] and vaccination [101].

Training (imparting skills)

Eleven reviews [104–114] (n = 165 studies) focused on training. Evidence from moderate- to high-quality reviews [104–114] reported that training on communication skills and cultural competency improved knowledge and professional expertise, which resulted in improved clinical outcomes including quality of life, well-being of patients with dementia, and reduced chronic disease in culturally and linguistically diverse communities [104–106, 108, 109, 113, 114].

Multiple interventions

Several reviews were focused on how to better manage chronic diseases using any behavior change interventions. To avoid misclassification, we classified these reviews under an umbrella term, multiple interventions. Forty-one reviews [31, 115–154] (n = 1375 studies) of poor- to high-quality focused on multiple interventions. The use of computer alerts within electronic medical records increased screening for sexually transmitted diseases [115]. Interventions in pharmacy services reduced suboptimal prescribing [117, 127, 133], and educational interventions improved primary healthcare providers’ identification, assessment, prevention and/or management of obesity in children and adolescents to achieve weight loss [121]. No review focused exclusively on audit and feedback, but multifaceted audit/feedback, reminders, educational outreach visits, and patient-mediated interventions [31, 116, 118, 119] were found to be effective in influencing health professionals’ prescribing practice. Financial incentives combined with educational interventions and audit/feedback have been found to be effective in increasing the practice of generic prescribing [124]. Multifaceted interventions where educational interventions occurred at many levels may be successfully incorporated into established medical communities after addressing local barriers to change [120, 123, 130, 153]. Advance practice nurse care [136], quality improvement strategies [137, 148–152], case management [138], collaborative care [140], evidence-based medicine practice strategies [144], midwife-led continuity services [145], comprehensive asthma care [146], and patient-centered medical home [125, 147] have all been evaluated. Moderate- to high-quality reviews demonstrated improved safety, quality care, increased vaccination rate, and improved management of patient with depression and anxiety in primary healthcare settings [135–137, 139–142, 144, 147, 148, 150, 151]. Few reviews failed to provide any conclusive outcomes [122, 126, 129, 131, 134, 143, 154, 155].

Policies (Additional file 1: Table S1)

Service provision (delivering a service)

Five reviews [156–160] (n = 44 studies) of poor- to high-quality evaluated effects of consultation time [156, 158], brief non-pharmacological interventions (computer-based cognitive-behavioral therapy) [157], and non-medical prescribing [159] (drug prescriptions by nurses, pharmacists, and allied health professionals) on behavioral change of primary healthcare professionals. While a health technology report [160] assessed evidence on specialized community-based care and concluded that specialized community-based care effectively improves outcomes in patients with heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetes. Bibliotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy-based websites, and cognitive behavioral therapy-based computer programs [157] found to be effective in improving management of patients with depression. Other reviews [156, 158, 159] were not found to be effective.

Communication (using print, electronic, telephone, or broadcast media)

Three reviews [161–163] (n = 44 studies) of moderate- to high-quality evaluated communication as an intervention reporting inconclusive results. One review [161] uniquely assessed whether patients benefit from improved communication between primary healthcare practitioners and nephrologists. The review found little evidence of benefit from enhancing the quality of letters from specialists to primary healthcare practitioners.

Guidelines (creating documents that recommend practice standards)

Two reviews [164, 165] (n = 42 studies) of moderate- to high-quality evaluated the impact of guidelines on the improvement of healthcare professionals’ practice. None of the interventions found to be effective method for increasing advance directive completion rates in the primary healthcare setting [164, 165].

Discussion

In our overview of reviews, we identified, classified, and evaluated the behavior change interventions and policies influencing practice change of primary healthcare professionals who primarily manage patients with chronic diseases at primary healthcare centers. Interactive and multifaceted continuous medical education programs including training with audit and feedback, and clinical decision support systems were found to be of benefit in improving knowledge, optimizing prescriptions, increasing screening rate, enhancing patient outcomes, and reducing adverse events. Limited evidence on environmental restructuring and modeling were found to be effective in improving collaboration and adherence to treatment guidelines. Collaborative team-based approaches involving primarily family physicians, nurses, and pharmacists were found to be effective. Limited evidence on nurse-led care approaches were found to be promising and warrant further evaluation using better study designs for different chronic diseases. Evidence clearly does not support the use of financial incentives to family physicians, especially for long-term sustained behavior and practice change.

To the best of our knowledge, so far this is the largest comprehensive overview of reviews evaluating authors’ reported efficacy of behavior change interventions and policies influencing primary healthcare professionals’ practice change and classified according to the behavior change wheel proposed by Michie et al. [15]. Our outcomes support the inferences reported by other overview reviews [166] and review [167] focused on individual interventions. Grimshaw and colleagues [166] reported that educational outreach (for prescribing) and reminders were found to be most promising approaches. Multifaceted interventions targeting different barriers to change are more likely to be effective than single interventions. We reported that education intervention found to be effective, especially when used as multifaceted interventions to achieve primary healthcare professionals’ practice change to improve quality of care and better manage patients with chronic diseases. Ivers and colleagues [167] reported audit and feedback generally leads to small but potentially important improvements in professional practice. We did not find any review exclusively evaluating audit and feedback on primary healthcare professionals; however, it was used with other interventions (e.g., education and training) and provided mixed results. With regards to financial incentives, Flodgren and colleagues have reported that financial incentives may be effective in changing healthcare professional practice [168]. In contrast, we found that financial incentives were not effective in practice change of family physicians working at primary healthcare centers.

This review did identify limited evidence on a few promising interventions, including nurse-led approaches and use of opinion leaders or specialists. Further, thorough evaluation in specific areas of interest should be performed before they are widely implemented in a healthcare setting.

To reduce the gap in quality of care and better manage patients with chronic diseases, behavioral interventions and supporting policies are essential. Through this overview of reviews, we attempted to provide an evidence to improve our understanding on which behavioral interventions and policies are effective to influence practice of primary healthcare professionals working in primary health care settings. This review is heavily weighted by evidence on family physicians, thus indicating the need for studies on other primary healthcare professionals. We excluded reviews that either evaluated these interventions and policies on specialists and hospital settings or included studies conducted exclusively in low- to middle-income countries, where the functionality of healthcare systems is different than Canada. Behavior change interventions or policies were classified based on the framework proposed by Michie and colleagues [15] and no other frameworks were explored or compared. Considering this is an overview of reviews and we have not performed a meta-analysis, we did not attempt to review individual studies from included reviews; there is a possibility of few studies might have been included by multiple reviews or might be a chance of over representation of outcomes. Evidence ranged from poor- to high-quality as well the high heterogeneity in interventions, study population, and outcomes prevented to generalize the conclusion to specific category of primary healthcare professionals or interventions and policies.

Conclusion

Behavior change interventions including interactive and multifaceted continuous medical education, training with audit and feedback, enablement through advanced information technology-based systems, and collaborative team-based interventions can effectively modify healthcare professionals’ practice and patient outcomes. Limited evidence exists to support environment restructuring and modeling. Nurse-led systems of care warrant further evaluation. Financial incentives to family physicians do not influence long-term behavior and practice change.

References

PHAC. Public health agency of Canada: chronic disease infobase. 2014.

Mirolla M. The cost of chronic disease in Canada. 2004.

Ronksley PE, Sanmartin C, Quan H, Ravani P, Tonelli M, Manns B, Hemmelgarn BR. Association between perceived unmet health care needs and risk of adverse health outcomes among patients with chronic medical conditions. Open Med. 2013;7:e21–30.

Sibley LM, Glazier RH. Many Canadians feel healthcare needs are not being met. Healthc Q. 2010;13:19–22.

Sanmartin C, Houle C, Tremblay S, Berthelot JM. Changes in unmet health care needs. Health Rep. 2002;13:15–21.

Davis K SC, Stremikis K. Mirror, mirror on the Wall: how the performance of the U.S. health care system compares internationally, 2010 Update. The Commonwealth Fund; 2010.

How Canada performs: health. Health Performance: Health Outcomes. 2011.

Parekh AK, Goodman RA, Gordon C, Koh HK. Managing multiple chronic conditions: a strategic framework for improving health outcomes and quality of life. Public Health Rep. 2011;126:460–71.

Bodenheimer T. Primary care--will it survive? N Engl J Med. 2006;355:861–4.

Williams JW JG, Powers BJ, Chatterjee R, Prvu Bettger J, Kemper AR, Hasselblad V, Dolor RJ, Irvine RJ, Heidenfelder BL, Kendrick AS, Gray R. The Patient Centered Medical Home. Closing the quality gap: revisiting the state of the science. In: Evidence report/technology assessment No 208 (Prepared by the Duke Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No 290-2007-10066-I). 2012.

Scholle STP, Peikes D, Han E, Genevro J. Engaging patients and families in the medical home (prepared by Mathematica Policy Research under contract no. HHSA290200900019ITO2.) AHRQ Publication no. 10-0083-EF. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010.

Stange KC, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Jaen CR, Crabtree BF, Flocke SA, Gill JM. Defining and measuring the patient-centered medical home. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:601–12.

Greenwood J, Nash DB. The impact of the patient-centered medical home on the biologics industry, employers, and third-party payers. Biotechnol Healthc. 2009;6:33–43.

Shi L. The impact of primary care: a focused review. Scientifica (Cairo). 2012;2012:432892.

Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42.

Cabana MD, Slish KK, Evans D, Mellins RB, Brown RW, Lin X, Kaciroti N, Clark NM. Impact of physician asthma care education on patient outcomes. Pediatrics. 2006;117:2149–57.

Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, McAlister FA. Impact of opinion leader-endorsed evidence summaries on the quality of prescribing for patients with cardiovascular disease: a randomized controlled trial. Am Heart J. 2007;153:22.e21–28.

Ettner SL, Thompson TJ, Stevens MR, Mangione CM, Kim C, Neil Steers W, Goewey J, Brown AF, Chung RS, Narayan KM. Are physician reimbursement strategies associated with processes of care and patient satisfaction for patients with diabetes in managed care? Health Serv Res. 2006;41:1221–41.

Fagan PJ, Schuster AB, Boyd C, Marsteller JA, Griswold M, Murphy SM, Dunbar L, Forrest CB. Chronic care improvement in primary care: evaluation of an integrated pay-for-performance and practice-based care coordination program among elderly patients with diabetes. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:1763–82.

Thepwongsa I, Kirby CN, Schattner P, Piterman L. Online continuing medical education (CME) for GPs: does it work? A systematic review. Aust Fam Physician. 2014;43:717–21.

Ginige S, Fairley CK, Hocking JS, Bowden FJ, Chen MY. Interventions for increasing chlamydia screening in primary care: a review. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:95.

Jackson GLP. The patient-centered medical home: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:169–78.

Donaldson KY M, Vanselow N. Defining primary care: An interim report. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1994.

Institute of Medicine Committee on the Future of Primary C. In: Donaldson M, Yordy K, Vanselow N, editors. Defining Primary Care: An Interim Report. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1994.

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C, Porter AC, Tugwell P, Moher D, Bouter LM. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:10.

EPHPP. Quality assessment tool for quantititative studies; 2010. http://www.ephpp.ca/PDF/Quality%20Assessment%20Tool_2010_2.pdf.

Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, Biondo PD, Cummings GG. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18:12–8.

Institute TJB. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual; 2014. http://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/sumari/reviewersmanual-2014.pdf.

Mostofian FR. Changing physician behavior: what works? Am J Manag Care. 2015;21:75–84.

Eijkenaar FE. Effects of pay for performance in health care: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Health Policy. 2013;110:115–30.

Grindrod KA, Patel P, Martin JE. What interventions should pharmacists employ to impact health practitioners’ prescribing practices? Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1546–57.

Chhina HK, Bhole VM, Goldsmith C, Hall W, Kaczorowski J, Lacaille D. Effectiveness of academic detailing to optimize medication prescribing behaviour of family physicians. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2013;16:511–29.

Velden AW, Pijpers EJ, Kuyvenhoven MM, Tonkin-Crine SKG, Little P, Verheij TJ. Effectiveness of physician-targeted interventions to improve antibiotic use for respiratory tract infections. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62:e801–7.

Thomas DC, Johnston B, Dunn K, Sullivan GM, Brett B, Matzko M, Levine SA. Continuing medical education, continuing professional development, and knowledge translation: improving care of older patients by practicing physicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1610–8.

Brody AA, Galvin JE. A review of interprofessional dissemination and education interventions for recognizing and managing dementia. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2013;34:225–56.

Schichtel M, Rose PW, Sellers C. Educational interventions for primary healthcare professionals to promote the early diagnosis of cancer: a systematic review. Educ Prim Care. 2013;24:274–90.

Hardy S, White J, Deane K, Gray R. Educating healthcare professionals to act on the physical health needs of people with serious mental illness: a systematic search for evidence. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18:721–7.

Miller A, Archer J. Impact of workplace based assessment on doctors’ education and performance: a systematic review. BMJ. 2010;341:c5064.

Lineker SC, Husted JA. Educational interventions for implementation of arthritis clinical practice guidelines in primary care: effects on health professional behavior. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1562–9.

Alvarez MP, Agra Y. Systematic review of educational interventions in palliative care for primary care physicians. Palliat Med. 2006;20:673–83.

Howe AA. Effectiveness of educational interventions in primary care mental health: a qualitative systematic review. Prim Care Community Psychiatry. 2006;11:167–77.

Kamarudin GP. Educational interventions to improve prescribing competency: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003291.

Thepwongsa I, Kirby C, Schattner P, Shaw J, Piterman L. Type 2 diabetes continuing medical education for general practitioners: what works? A systematic review. Diabet Med. 2014;31:1488–97.

Perry M, Draskovic I, Lucassen P, Vernooij-Dassen M, van Achterberg T, Rikkert MO. Effects of educational interventions on primary dementia care: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:1–11.

Vodicka TA, Thompson M, Lucas P, Heneghan C, Blair PS, Buckley DI, Redmond N, Hay AD, TARGET Programme team. Reducing antibiotic prescribing for children with respiratory tract infections in primary care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:e445–54.

Guldberg TL, Lauritzen T, Kristensen JK, Vedsted P. The effect of feedback to general practitioners on quality of care for people with type 2 diabetes. A systematic review of the literature. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10:30.

Cheraghi-Sohi S, Bower P. Can the feedback of patient assessments, brief training, or their combination, improve the interpersonal skills of primary care physicians? A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:179.

Ring N, Malcolm C, Wyke S, Macgillivray S, Dixon D, Hoskins G, Pinnock H, Sheikh A. Promoting the use of Personal Asthma Action Plans: a systematic review. Prim Care Respir J. 2007;16:271–83.

Rourke L, Oberholtzer S, Chatterley T, Brassard A. Learning to detect, categorize, and identify skin lesions: a meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:293–301.

Reinders ME, Ryan BL, Blankenstein AH, van der Horst HE, Stewart MA, van Marwijk HW. The effect of patient feedback on physicians’ consultation skills: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2011;86:1426–36.

Gijbels HOC. A systematic review evaluating the impact of post-registration nursing and midwifery education on practice. Nurse Educ Pract. 2010;10:64–9.

Zaher E, Ratnapalan S. Practice-based small group learning programs: systematic review. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:637–42.

Curti S, Sauni R, Spreeuwers D, De SA, Valenty M, Riviere S, Mattioli S. Interventions to increase the reporting of occupational diseases by physicians. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;3:CD010305.

Goulart JM, Quigley EA, Dusza S, Jewell ST, Alexander G, Asgari MM, Eide MJ, Fletcher SW, Geller AC, Marghoob AA, et al. Skin cancer education for primary care physicians: a systematic review of published evaluated interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1027–35.

Omidvari AH, Vali Y, Murray SM, Wonderling D, Rashidian A. Nutritional screening for improving professional practice for patient outcomes in hospital and primary care settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6:CD005539.

Benthem GH, Heg RR, Leeuwen YD, Metsemakers JF. Teaching psychiatric diagnostics to general practitioners: educational methods and their perceived efficacy. Med Teach. 2009;31:e279–86.

Adaji A, Schattner P, Jones K. The use of information technology to enhance diabetes management in primary care: a literature review. Inform Prim Care. 2008;16:229–37.

de Lusignan S, Mold F, Sheikh A, Majeed A, Wyatt JC, Quinn T, Cavill M, Gronlund TA, Franco C, Chauhan U, et al. Patients’ online access to their electronic health records and linked online services: a systematic interpretative review. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e006021. 002014.

Pires CM, Cavaco AM. Communication between health professionals and patients: review of studies using the RIAS (Roter Interaction Analysis System) method. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2014;60:156–72.

Holstiege J, Mathes T, Pieper D. Effects of computer-aided clinical decision support systems in improving antibiotic prescribing by primary care providers: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22:236–42.

Dixon BE, Gamache RE, Grannis SJ. Towards public health decision support: a systematic review of bidirectional communication approaches. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20:577–83.

Robertson J, Walkom E, Pearson SA, Hains I, Williamsone M, Newby D. The impact of pharmacy computerised clinical decision support on prescribing, clinical and patient outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Pharm Pract. 2010;18:69–87.

Curtain CP. Review of computerized clinical decision support in community pharmacy. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2014;39:343–8.

Souza NM, Sebaldt RJ, Mackay JA, Prorok JC, Weise-Kelly L, Navarro T, Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB, Team CSR. Computerized clinical decision support systems for primary preventive care: a decision-maker-researcher partnership systematic review of effects on process of care and patient outcomes. Implement Sci. 2011;6:87.

Fathima M, Peiris D, Naik-Panvelkar P, Saini B, Armour CL. Effectiveness of computerized clinical decision support systems for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary care: a systematic review. BMC Polm Med. 2014;14:189.

Cleveringa FG, Gorter KJ, van den Donk M, van Gijsel J, Rutten GE. Computerized decision support systems in primary care for type 2 diabetes patients only improve patients’ outcomes when combined with feedback on performance and case management: a systematic review. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2013;15:180–92.

Calabretto JPW. Pharmacy decision support: Where is it? A systematic literature review. Int J Pharm Pract. 2005;13:157–63.

Boyle RG, Solberg LI, Fiore MC. Electronic medical records to increase the clinical treatment of tobacco dependence: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39:S77–82.

Lainer M, Mann E, Sonnichsen A. Information technology interventions to improve medication safety in primary care: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2013;25:590–8.

Huang Y, Chen R, Wu T, Wei X, Guo A. Association between point-of-care CRP testing and antibiotic prescribing in respiratory tract infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis of primary care studies (Provisional abstract). Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:e787–94.

Gialamas ASJ. Point-of-care testing for patients with diabetes, hyperlipidaemia or coagulation disorders in the general practice setting: A systematic review. Fam Pract. 2010;27:17–24.

Motulsky AL. Impacts of second-generation electronic prescriptions on the medication management process in primary care: A systematic review. Int J Med Inform. 2013;82:473–91.

Damiani G, Silvestrini G, Federico B, Cosentino M, Marvulli M, Tirabassi F, Ricciardi W. A systematic review on the effectiveness of group versus single-handed practice. Health Policy. 2013;113:180–7.

Riley SB, Marshall ES. Group visits in diabetes care: a systematic review. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36:936–44.

Unverzagt S, Oemler M, Braun K, Klement A. Strategies for guideline implementation in primary care focusing on patients with cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2014;31:247–66.

Gilbody S, Sheldon T, House A. Screening and case-finding instruments for depression: a meta-analysis. Can Med Assoc J. 2008;178:997–1003.

Legare F, Ratte S, Stacey D, Kryworuchko J, Gravel K, Graham ID, Turcotte S. Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;5:CD006732.

Smith SM, Allwright S, O’Dowd T. Effectiveness of shared care across the interface between primary and specialty care in chronic disease management. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;3:CD004910.

Mitchell GK, Brown RM, Erikssen L, Tieman JJ. Multidisciplinary care planning in the primary care management of completed stroke: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9:44.

Page T, Lockwood C, Conroy-Hiller T. Effectiveness of nurse-led cardiac clinics in adult patients with a diagnosis of coronary heart disease. Int J Evid-Based Health. 2005;3:2–26.

Kuethe MC, Vaessen-Verberne AA, Elbers RG, Van Aalderen WM. Nurse versus physician-led care for the management of asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD009296.

Carey N, Courtenay M. A review of the activity and effects of nurse-led care in diabetes. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:296–304.

Desborough J, Forrest L, Parker R. Nurse-led primary healthcare walk-in centres: an integrative literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68:248–63.

Urquhart C, Currell R, Grant MJ, Hardiker NR. Nursing record systems: effects on nursing practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;1:CD002099.

Martelly MTS. Effect of substituting nurses for doctors in primary care. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2014;21:398–9.

Laurant M, Reeves D, Hermens R, Braspenning J, Grol R, Sibbald B. Substitution of doctors by nurses in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2:CD001271.

Courtenay M, Carey N. The impact and effectiveness of nurse-led care in the management of acute and chronic pain: a review of the literature. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17:2001–13.

Dennis S, May J, Perkins D, Zwar N, Sibbald B, Hasan I. What evidence is there to support skill mix changes between GPs, pharmacists and practice nurses in the care of elderly people living in the community? Aust N Z Health Policy. 2009;6:23.

Health QO. Specialized nursing practice for chronic disease management in the primary care setting: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2013;13:1–66.

Proia KK, Thota AB, Njie GJ, Finnie RK, Hopkins DP, Mukhtar Q, Pronk NP, Zeigler D, Kottke TE, Rask KJ, et al. Team-based care and improved blood pressure control: a community guide systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47:86–99.

Schadewaldt V, Schultz T. Nurse-led clinics as an effective service for cardiac patients: results from a systematic review. Int J Evid-Based Health. 2011;9:199–214.

Scott A, Sivey P, Ait OD, Willenberg L, Naccarella L, Furler J, Young D. The effect of financial incentives on the quality of health care provided by primary care physicians. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;9:CD008451.

McDonald J, Harris MF, Cumming J, Powell DG, Burns P. The implementation and impact of different funding initiatives on access to multidisciplinary primary health care and policy implications. Med J Aust. 2008;188:S69–72.

Langdown C, Peckham S. The use of financial incentives to help improve health outcomes: is the quality and outcomes framework fit for purpose? A systematic review. J Public Health (Oxf). 2014;36:251–8.

Houle SK, McAlister FA, Jackevicius CA, Chuck AW, Tsuyuki RT. Does performance-based remuneration for individual health care practitioners affect patient care?: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:889–99.

Gillam SJ, Siriwardena AN, Steel N. Pay-for-performance in the United Kingdom: impact of the quality and outcomes framework: a systematic review. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:461–8.

Vahidi RGM. A systematic review of the effect of payment mechanisms on family physicians service provision and referral rate behavior. J Pak Med Students. 2013;3:54–60.

Flodgren G, Parmelli E, Doumit G, Gattellari M, O’Brien MA, Grimshaw J, Eccles MP. Local opinion leaders: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;8:CD000125.

Harkness EF, Bower PJ. On-site mental health workers delivering psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions to patients in primary care: effects on the professional practice of primary care providers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;1:CD000532.

Jenkins HJ, Hancock MJ, French SD, Maher CG, Engel RM, Magnussen JS. Effectiveness of interventions designed to reduce the use of imaging for low-back pain: a systematic review. Can Med Assoc J. 2015;187:401–8.

Holt TAT. Changing clinical practice through patient specific reminders available at the time of the clinical encounter: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:974–84.

Siddiqui MR, Sajid MS, Khatri K, Kanri B, Cheek E, Baig MK. The role of physician reminders in faecal occult blood testing for colorectal cancer screening. Eur J Gen Pract. 2011;17:221–8.

Lu CYR. Interventions designed to improve the quality and efficiency of medication use in managed care: A critical review of the literature - 2001-2007. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:75.

Moore PM, Rivera MS, Grez AM, Lawrie TA. Communication skills training for healthcare professionals working with people who have cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3:CD003751.

Eggenberger EH. Communication skills training in dementia care: a systematic review of effectiveness, training content, and didactic methods in different care settings. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25:345–58.

Horvat L, Horey D, Romios P, Kis-Rigo J. Cultural competence education for health professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;5:CD009405.

Lie DA, Lee-Rey E, Gomez A, Bereknyei S, Braddock III CH. Does cultural competency training of health professionals improve patient outcomes? A systematic review and proposed algorithm for future research. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:317–25.

Henderson S, Kendall E, See L. The effectiveness of culturally appropriate interventions to manage or prevent chronic disease in culturally and linguistically diverse communities: a systematic literature review. Health Soc Care Community. 2011;19:225–49.

Soderlund LLM. A systematic review of motivational interviewing training for general health care practitioners. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84:16–26.

Rashid C. Benefits and limitations of nurses taking on aspects of the clinical role of doctors in primary care: integrative literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66:1658–70.

Mesquita AR, Lyra Jr DP, Brito GC, Balisa-Rocha BJ, Aguiar PM, de Almeida Neto AC. Developing communication skills in pharmacy: a systematic review of the use of simulated patient methods. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78:143–8.

Xu T, de Almeida Neto AC, Moles RJ. A systematic review of simulated-patient methods used in community pharmacy to assess the provision of non-prescription medicines. Int J Pharm Pract. 2012;20:307–19.

Sikorski C, Luppa M, Konig HH, van den Bussche H, Riedel-Heller SG. Does GP training in depression care affect patient outcome? - A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res [electronic resource]. 2012;12:10.

Paskins Z, McHugh G, Hassell AB. Getting under the skin of the primary care consultation using video stimulated recall: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol [electronic resource]. 2014;14:101.

Zou H, Fairley CK, Guy R, Chen MY. The efficacy of clinic-based interventions aimed at increasing screening for bacterial sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men: a systematic review. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39:382–7.

Dwamena F, Holmes-Rovner M, Gaulden CM, Jorgenson S, Sadigh G, Sikorskii A, Lewin S, Smith RC, Coffey J, Olomu A. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD003267.

Castelino RL, Bajorek BV, Chen TF. Targeting suboptimal prescribing in the elderly: a review of the impact of pharmacy services. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:1096–106.

Mansell G, Shapley M, Jordan JL, Jordan K. Interventions to reduce primary care delay in cancer referral: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61:e821–35.

Guy RJ, Ali H, Liu B, Poznanski S, Ward J, Donovan B, Kaldor J, Hocking J. Efficacy of interventions to increase the uptake of chlamydia screening in primary care: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis [electronic resource]. 2011;11:211.

Laliberte MC, Perreault S, Jouini G, Shea BJ, Lalonde L. Effectiveness of interventions to improve the detection and treatment of osteoporosis in primary care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:2743–68.

Jacobson D, Gance-Cleveland B. A systematic review of primary healthcare provider education and training using the Chronic Care Model for childhood obesity. Obes Rev. 2011;12:e244–56.

Dennis SM, Zwar N, Griffiths R, Roland M, Hasan I, Powell DG, Harris M. Chronic disease management in primary care: from evidence to policy. Med J Aust. 2008;188:S53–6.

Arnold SR, Straus SE. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices in ambulatory care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;4:CD003539.

Moe-Byrne TC. Behaviour change interventions to promote prescribing of generic drugs: a rapid evidence synthesis and systematic review. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004623.

McMillan SSK. Patient-centered approaches to health care: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70:567–96.

Loganathan MS. Interventions to optimise prescribing in care homes: systematic review. Age Ageing. 2011;40:150–62.

Kaur SM. Interventions that can reduce inappropriate prescribing in the elderly: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2009;26:1013–28.

Okelo SO, Butz AM, Sharma R, Diette GB, Pitts SI, King TM, Linn ST, Reuben M, Chelladurai Y, Robinson KA. Interventions to modify health care provider adherence to asthma guidelines. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013.

Huijg JM, Gebhardt WA, Verheijden MW, Zouwe N, Vries JD, Middelkoop BJ, Crone MR. Factors influencing primary health care professionals’ physical activity promotion behaviors: a systematic review. J Behav Med. 2014;epub.

Fahey T, Schroeder K, Ebrahim S. Educational and organisational interventions used to improve the management of hypertension in primary care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:875–82.

McKinstry B, Ashcroft RE, Car J, Freeman GK, Sheikh A. Interventions for improving patients’ trust in doctors and groups of doctors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD004134.

Akbari A, Mayhew A, Al-Alawi MA, Grimshaw J, Winkens R, Glidewell E, Pritchard C, Thomas R, Fraser C. Interventions to improve outpatient referrals from primary care to secondary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;4:CD005471.

Gunten V, Reymond JP, Beney J. Clinical and economic outcomes of pharmaceutical services related to antibiotic use: a literature review. Pharm World Sci. 2007;29:146–63.

Beach MC, Gary TL, Price EG, Robinson K, Gozu A, Palacio A, Smarth C, Jenckes M, Feuerstein C, Bass EB, et al. Improving health care quality for racial/ethnic minorities: a systematic review of the best evidence regarding provider and organization interventions. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:104.

Smit AT. Improving long-term outcome of depression in primary care: a review of RCTs with psychological and supportive interventions. Eur J Psychiatry. 2007;21:37–48.

Newhouse R, Stanik-Hutt J, White K, Johantgen M, Bass E, Zangaro G, Wilson R, Fountain L, Steinwachs D, Heindel L, Weiner J. Advanced practice nurse outcomes 1990-2008: a systematic review. Nurs Econ. 2011;29:230–51.

Lau D, Hu J, Majumdar SR, Storie DA, Rees SE, Johnson JA. Interventions to improve influenza and pneumococcal vaccination rates among community-dwelling adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:538–46.

Saxena S, Misra T, Car J, Netuveli G, Smith R, Majeed A. Systematic review of primary healthcare interventions to improve diabetes outcomes in minority ethnic groups. J Ambul Care Manage. 2007;30:218–30.

Majka AJ, Wang Z, Schmitz KR, Niesen CR, Larsen RA, Kinsey GC, Murad AL, Prokop LJ, Murad MH. Care coordination to enhance management of long-term enteral tube feeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2014;38:40–52.

Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, Lovell K, Richards D, Gask L, Dickens C, Coventry P. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006525.

Thota AB, Sipe TA, Byard GJ, Zometa CS, Hahn RA, McKnight-Eily LR, Chapman DP, Abraido-Lanza AF, Pearson JL, Anderson CW, et al. Collaborative care to improve the management of depressive disorders: a community guide systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42:525–38.

Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Gulliver A, Clack D, Kljakovic M, Wells L. Models in the delivery of depression care: a systematic review of randomised and controlled intervention trials. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9:25.

Phillips CB, Pearce CM, Hall S, Travaglia J, de Lusignan S, Love T, Kljakovic M. Can clinical governance deliver quality improvement in Australian general practice and primary care? A systematic review of the evidence. Med J Aust. 2010;193:602–7.

de Belvis AG, Pelone F, Biasco A, Ricciardi W, Volpe M. Can primary care professionals’ adherence to Evidence Based Medicine tools improve quality of care in type 2 diabetes mellitus? A systematic review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;85:119–31.

Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, Shennan A, Devane D. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD004667.

Baishnab E, Karner C. Primary care based clinics for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD003533.

Jackson GL, Powers BJ, Chatterjee R, Bettger JP, Kemper AR, Hasselblad V, Dolor RJ, Irvine RJ, Heidenfelder BL, Kendrick AS, et al. Improving patient care. The patient centered medical home. a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:169–78.

Van Cleave JK. Interventions to improve screening and follow-up in primary care: a systematic review of the evidence. Acad Pediatr. 2012;12:269–82.

Shojania KGR. Effects of quality improvement strategies for type 2 diabetes on glycemic control: a meta-regression analysis. JAMA. 2006;296:427–40.

Tory HOS. Analysis of quality improvement efforts in preventing glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;44:483–8.

Gallagher H, de Lusignan S, Harris K, Cates C. Quality-improvement strategies for the management of hypertension in chronic kidney disease in primary care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60:e258–65.

Ranji SR, Steinman MA, Shojania KG, Gonzales R. Interventions to reduce unnecessary antibiotic prescribing: a systematic review and quantitative analysis. Med Care. 2008;46:847–62.

Gask L, Dowrick C, Salmon P, Peters S, Morriss R. Reattribution reconsidered: narrative review and reflections on an educational intervention for medically unexplained symptoms in primary care settings. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71:325–34.

Rolfe A, Cash-Gibson L, Car J, Sheikh A, McKinstry B. Interventions for improving patients’ trust in doctors and groups of doctors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;3:CD004134.

Grimshaw JM, Winkens RA, Shirran L, Cunningham C, Mayhew A, Thomas R, Fraser C. Interventions to improve outpatient referrals from primary care to secondary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3:CD005471.

Wilson A, Childs S. The effect of interventions to alter the consultation length of family physicians: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56:876–82.

McNaughton JL. Brief interventions for depression in primary care: a systematic review. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:789–96.

Wilson AD, Childs S. Effects of interventions aimed at changing the length of primary care physicians’ consultation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;1:CD003540.

Bhanbhro S, Drennan VM, Grant R, Harris R. Assessing the contribution of prescribing in primary care by nurses and professionals allied to medicine: a systematic review of literature. BMC Health Serv Res [electronic resource]. 2011;11:330.

Specialized community-based care: An evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2012;12.

Jiwa M, Chakera A, Dadich A, Ossolinski G, Hewitt V. The impact of the quality of communication from nephrologists to primary care practitioners: a literature review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30:2093–101.

Cant R, Pomeroy S. Facilitating patients’ dietary change: a review of dietitians’ correspondence practices with general practitioners. Nutr Diet. 2011;68:140–8.

Sawmynaden P, Atherton H, Majeed A, Car J. Email for the provision of information on disease prevention and health promotion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD007982.

Ramsaroop SD, Reid MC, Adelman RD. Completing an advance directive in the primary care setting: what do we need for success? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:277–83.

Clarke A, Blundell N, Forde I, Musila N, Spitzer D, Naqvi S, Browne J. Can guidelines improve referral to elective surgical specialties for adults? A systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:187–94.

Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R, Mowatt G, Fraser C, Bero L, Grilli R, Harvey E, Oxman A, O’Brien MA. Changing provider behavior: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Med Care. 2001;39:II2–II45.

Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Young JM, Odgaard-Jensen J, French SD, O’Brien MA, Johansen M, Grimshaw J, Oxman AD. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6:CD000259.

Flodgren G, Eccles MP, Shepperd S, Scott A, Parmelli E, Beyer FR. An overview of reviews evaluating the effectiveness of financial incentives in changing healthcare professional behaviours and patient outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;7:CD009255.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Kristin Anderson, Lindsay Story, and Nathan Hoeppner from Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living for their suggestions and comments on the subject, as well as the protocol of the overview.

Funding

None. Dr. Zarychanski is a recipient of the New Investigator Salary Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Availability of data and materials

For the additional information on data and material presented in this manuscript, please contact the corresponding author.

Authors’ contributions

Dr. BFC played a role in the conceptualization of the project, wrote the protocol, led and coordinated this overview, screened citations, assessed studies for eligibility, extracted data, performed quality assessments, drafted and revised the manuscript, approved the final version of the manuscript as submitted, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects pertaining to the overview. Drs. MJ, ASM, and JL screened citations, assessed studies for eligibility, extracted data, and performed methodological quality assessments. Drs. KMS, AA-S, and RZ and played a key role in the conceptualization of the project and provided methodological expertise during the protocol development and conduct of the overview. They critically reviewed and provided expert comments on the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript. BS played an important role in designing and executing the search strategy, provided relevant comments on the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

This article is based on research conducted by the Knowledge Synthesis Platform, George and Fay Yee Centre for Healthcare Innovation, Winnipeg, Canada under the request made from the Primary Health Care Branch, Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living, Government of Manitoba, Canada. The authors of this article are responsible for its contents, including the conclusion and any inference derived from the included evidence. Results and conclusions are those of the author(s) and no official endorsement by Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living is intended or should be inferred.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0568-x.

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Outcomes and methodological quality assessment of included reviews. (DOC 662 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chauhan, B.F., Jeyaraman, M., Mann, A.S. et al. Behavior change interventions and policies influencing primary healthcare professionals’ practice—an overview of reviews. Implementation Sci 12, 3 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0538-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0538-8