Abstract

Background

There is a paucity of translational research programmes to improve implementation of evidence-based care in drug and alcohol settings. This systematic review aimed to provide a synthesis and evaluation of the effectiveness of implementation programmes of treatment for patients with drug and alcohol problems using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR).

Methods

A comprehensive systematic review was conducted using five online databases (from inception onwards). Eligible studies included clinical trials and observational studies evaluating strategies used to implement evidence-based psychosocial treatments for alcohol and substance use disorders. Extracted data were qualitatively synthesised for common themes according to the CFIR. Primary outcomes included the implementation, service system or clinical practice. Risk of bias of individual studies was appraised using appropriate tools. A protocol was registered with (PROSPERO) (CRD42019123812) and published previously (Louie et al. Systematic 9:2020).

Results

Of the 2965 references identified, twenty studies were included in this review. Implementation research has employed a wide range of strategies to train clinicians in a few key evidence-based approaches to treatment. Implementation strategies were informed by a range of theories, with only two studies using an implementation framework (Baer et al. J Substance Abuse Treatment 37:191-202, 2009) used Context-Tailored Training and Helseth et al. J Substance Abuse Treatment 95:26-34, 2018) used the CFIR). Thirty of the 36 subdomains of the CFIR were evaluated by included studies, but the majority were concerned with the Characteristics of Individuals domain (75%), with less than half measuring Intervention Characteristics (45%) and Inner Setting constructs (25%), and only one study measuring the Outer Setting and Process domains. The most common primary outcome was the effectiveness of implementation strategies on treatment fidelity. Although several studies found clinician characteristics influenced the implementation outcome (40%) and many obtained clinical outcomes (40%), only five studies measured service system outcomes and only four studies evaluated the implementation.

Conclusions

While research has begun to accumulate in domains such as Characteristics of Individuals and Intervention Characteristics (e.g. education, beliefs and attitudes and organisational openness to new techniques), this review has identified significant gaps in the remaining CFIR domains including organisational factors, external forces and factors related to the process of the implementation itself. Findings of the review highlight important areas for future research and the utility of applying comprehensive implementation frameworks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is a lack of evidence-based treatment approaches being practised in drug and alcohol settings [1,2,3]. Evidence-based treatments including addiction medications, psychosocial therapies or integrated services are estimated to have been provided by no more than 25% of community services treating substance use disorders (SUDs) or co-occurring mental health disorders [4]. Furthermore, known effective treatments for SUDs are not routinely practised [3, 5, 6]. Bridging this gap requires a systematic assessment of the barriers that exist at multiple levels of healthcare delivery including the patient level, the provider level and the organisational level, and an associated plan for overcoming these barriers [7]. Bridging factors can be identified that work between system and organisational levels or interorganisational networks [8]. This would provide valuable information for clinicians and treatment services designed to ultimately address the pervasive harms associated with drug and alcohol use disorders.

Identifying evidence-based interventions for SUDs rather than developing an evidence-based implementation strategy appears to have previously received more focus [9] whereby research is generally conducted under controlled conditions that may not translate when implemented in practice settings. To this degree, the knowledge accumulated by the field of implementation science has informed the process of effectively implementing innovations and understanding treatment outcomes as distinct from implementation outcomes [10, 11]. Despite the high burden of disease [12] and the sizable gap between research and practice, the addictions field is grossly underrepresented within implementation science [4]. The application of implementation science to the implementation of evidence-based treatment of SUDs is therefore a priority.

Several frameworks have been developed appropriate for public sector services that have high utility in formulating implementation strategies, identifying appropriate assessments and assessing determinants and mechanisms (e.g. [13, 14], CFIR, 15 below). In the specific context of SUD research, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research [15] has been suggested to be an appropriate taxonomy [11]. The CFIR includes five domains of influence derived from a consolidation of the plethora of terms and concepts generated by implementation researchers: (1) intervention characteristics (e.g. evidence strength and quality, adaptability), (2) outer setting (e.g. patient needs and resources, external policies and incentives), (3) inner setting (e.g. implementation climate, readiness for implementation), (4) individuals involved (e.g. self-efficacy, knowledge and beliefs about the intervention), and (5) the implementation process (e.g. engaging members of the organisation, executing the innovation). A particular strength of the CFIR is the way in which it assists with differentiating the core components from the adaptive components of the intervention [3, 16], provides a platform for formative evaluation in implementation research and allows for the development and evaluation of models designed to predict the determinants of implementation outcomes and sustainability in a given context [11]. Another potential use for the CFIR is the assessment of how comprehensive an implementation strategy has been [17, 18]. Due to the relationship between the domains of the CFIR and the implementation outcomes, it has been categorised as a “determinant framework” [19]. As one of many determinant frameworks in the implementation research literature, the CFIR is distinguished by its comprehensive approach to synthesising implementation research. The incorporation of inner and outer setting domains in addition to clinician characteristics is of particular importance in the drug and alcohol field, which operates within these contexts. These attributes, as well as its utility in previous reviews and the SUD context, have made it the most appropriate evaluation framework for this review.

There are considerably less empirical evaluations of implementation strategies in SUD settings [20] than those found in the broader field of health care [17]. Reviews conducted to date have primarily been concerned with prevention (e.g. [21, 22]), treatment efficacy (e.g. [23, 24]) and specific interventions (e.g. [25, 26]). Where implementation strategies have been identified, the focus of the review has been on strategies addressing specific factors (e.g. [27]) or relationships between factors (e.g. [28]) related to implementation outcomes, but there has not been a comprehensive account of implementation effectiveness. One previous review of the implementation of SUD treatment [25] specifically focused on one type of intervention (integrated care). A thorough synthesis of implementation strategies in the SUD field in general, using an appropriate framework such as the CFIR is required to guide the design of translational research programmes to improve implementation of evidence-based care in drug and alcohol settings.

The objectives of this systematic review are thus to synthesise and evaluate the effectiveness of implementation programmes for psychosocial treatment of patients with drug and alcohol problems with regard to the five domains of influence outlined by the CFIR framework.

Methods

The present review is being reported in accordance with the reporting guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P) statement [29], see Additional file 1. A protocol was registered within the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (registration number: CRD42019123812) and published previously [30].

Eligibility criteria

Criteria for considering studies for this review were classified by:

Population

In order to meet inclusion criteria, studies had to involve an evaluation of implementation strategies used to transfer an evidence-based psychosocial treatment or treatment guideline into clinical practice in drug and alcohol settings. Implementation strategies were defined as an integrated set of methods or techniques that facilitate the adoption, implementation and sustainability of best practice [31]. Examples of discrete categories of implementation strategies included in this review have been most clearly articulated by Powell et al. [32]. Psychosocial treatments included any attempt to affect change in patients’ substance use through behaviour, cognition, affect, interpersonal relationships or environment (e.g. employment, housing). Participants in these studies included any clinician providing psychosocial interventions to patients accessing outpatient or inpatient drug and alcohol services. “Clinician” was defined as an individual employed to implement change in patients’ substance use using psychosocial treatments exclusively. As such, studies were excluded from the review if they focused on the development of psychometric instruments, drugs in sport, harm prevention or community awareness.

Intervention

To be eligible, the psychosocial intervention had to be evidence-based and provide clear recommendations for practice. Studies were excluded if they involved physiological, pharmacological (except where concurrent medication was provided but was not part of the study intervention primarily being examined or implemented), or education-based interventions. Information including the nature of desired change, strategies employed, source of the intervention, mode of delivery (individual or group), identification of who delivered the intervention, and the timing, duration and frequency of the intervention had to be stated clearly. Only ethically approved studies were considered.

Comparator and study design

Only studies with a comparison group were included. Comparisons could be made before and after the administration of the intervention, between two or more forms of intervention, or between different types of intervention(s) (or no intervention). We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomised controlled trials, observational studies including before-and-after studies, and time series analyses.

Outcomes

Primary study outcomes were adapted from previous studies [9, 33], and included implementation, service system or clinical practice. Specifically, outcomes covered categories such as fidelity, attitudes towards or satisfaction with the intervention, adoption, appropriateness of the intervention to the target population, implementation costs, the feasibility of the intervention within the setting and the sustainability of the intervention after implementation [33]. The length of post-intervention follow-up period had to be specified and any possible ceiling effects identified. Outcomes needed to be related to the effectiveness of the implementation process, as distinct from the efficacy of the intervention itself.

Setting

Since drug and alcohol inpatient and outpatient treatment settings that provide counselling services to patients are the focus of the review, settings such as primary care, criminal justice or those investigating cross-cultural factors were excluded from the review.

Information sources

The following electronic databases were searched (from inception to April 2020): PubMed/MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and CINAHL. Reference searches of relevant reviews and articles were also conducted. Similarly, a grey literature search was done with help of Google and the Grey Matters tool which is a checklist of health-related sites organised by topic. The tool is produced by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) [34].

Search strategy

The search included all relevant peer-reviewed studies. The search was conducted across 4 relevant concepts (see draft strategy in Additional file 2): (1) implementation, (2) evidence-based practices, (3) drug and alcohol service setting and (4) eligible research designs. The MEDLINE search strategy is available in Additional file 2.

Selection and data extraction

Two reviewers independently screened all articles identified from the search. First, titles and abstracts of articles returned from initial searches were screened based on the eligibility criteria outlined above. Second, full texts were examined in detail and screened for eligibility. Third, references of all considered articles were hand-searched to identify any relevant report missed in the search strategy by two reviewers independently. Any disagreement between reviewers was resolved by discussion to meet a consensus. EndNote version X9 (Clarivate Analytics) was used to manage all records.

Two researchers extracted data and organised it into variables based on the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Data Abstraction Form (e.g. clinical interventions, strategies, outcomes, and results), the conceptual model of Proctor et al. [9] (implementation, service system and clinical outcomes), information about any specific implementation frameworks used and a checklist of items aligned with the domains and subdomains of the CFIR (i.e. subdomains associated with intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, characteristics of individuals, and the implementation process; see Table 1). This method was used effectively in two previous reviews [18, 35] as a means of categorising the types of implementation strategies addressed by each of the studies included in the review.

Risk of bias of individual studies

All included studies were critically evaluated by two researchers independently using the Revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool (RoB 2) [22]. The RoB 2 provides a systematic assessment across five domains of bias (the randomisation process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, and selection of the reported results) to assess quality of the article per outcome. For cluster-randomised studies, an additional domain was used when assessing the randomisation process. Trial registries were also checked to determine the integrity of reported outcome measures and statistical methods. The grey literature search also assisted with identifying publication bias.

Data synthesis

Included studies did not have sufficient characteristics for a meta-analysis and therefore a narrative synthesis was performed. The main methods of synthesis involved tabulation using “meta-matrices” [36], textual descriptions, qualitative synthesis of themes [37] and content analysis to determine the frequency of categorised data [38]. The findings from the included articles were synthesised using the CFIR framework.

Results

Search results

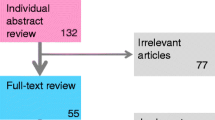

As displayed in the flowchart (Fig. 1), the database search identified 2965 studies. After titles were screened, 159 studies were found to be relevant (103 of which were replicas). Abstracts of the remaining studies were screened and 26 were found to meet inclusion criteria. Finally, full-text articles of these studies were assessed for eligibility and 19 were included in the review. An additional, identical search was conducted to capture any further relevant studies conducted between the time the first search was conducted until April 2020. This search identified 91 studies, one of which met eligibility criteria and was included in the review. An outline of the main features of included studies is provided in Table 2, including the type of innovation, guiding theories, strategies employed, study design, treatment setting, participant characteristics, study outcomes, CFIR domains evaluated, and the effectiveness of the implementation.

Treatment settings and participant characteristics of included studies

The majority of studies (16, 80% [39, 42, 45, 47, 54, 59,60,61,62, 65, 66, 68,69,70,71]) were conducted in the United States of America (USA), outpatient, not-for-profit drug and alcohol services. Alternate settings included one USA adolescent day programme affiliated with the University of Miami Medical School and Jackson Memorial Hospital [55], one outpatient drug and alcohol service affiliated with a university hospital in Switzerland [46], one drug abuse treatment organisation in Peru funded by a US Department of State contract [50], and one involved outpatient addiction treatment centres in South Africa [67]. Study participants were most often female (50–82%) drug and alcohol clinicians, with a mean age ranging from 37 to 48 years. Participants were also mostly Caucasian (50–100% in US studies) and were otherwise African American (14 to 40%), Hispanic (7 to 50%) or some other type of ethnicity (1 to 12.6%). In the South African study participants were also mainly Caucasian (36.4%), with Africans representing 30.8%, 12.6% identifying as “mixed-race”, and 14% Other. Participants commonly held bachelor’s degrees or higher (54 to 100%) and had 3+ to 9.5 years of experience.

Study designs

Nine (45%) of included studies were randomised controlled trials [59, 61, 62, 65,66,67,68,69], eight (40%) were randomised trials [39, 42, 43, 50, 54, 60, 70, 71](one of which was a subject-by-trial split plot design with repeated measures, [50]), one was a cluster randomised trial [45], one was an interrupted time series design [55], and one was a controlled before-and-after study [47]. Studies varied in terms of the number of participants, the length of follow-up period, the number of addiction services clinicians were sourced from, and the levels of intervention in the approach.

Types of strategies evaluated

All included studies were concerned with training as an implementation strategy. Approximately one third (n = 7) used multiple strategies that involved both passive (e.g. manuals and seminars) and active (e.g. supervision, workshops and champions) approaches to training [47, 59, 62, 65, 66, 68, 71], while 20% (n = 4) focused on discrete strategies (e.g. supervision [61], financial incentives [45], booster sessions [50], and workshop only [46]). Another third (n = 6) used technological strategies such as teleconferencing and web-based training [42, 54, 67,68,69,70]. Three studies (15%) focused on the influence of the intervention context on the uptake of the intervention [39, 55, 60].

Theories, models and frameworks

Fixsen and colleagues’ [16] conceptualisation of the implementation literature was the most frequently cited (3 of the 20 studies). These studies [59, 60, 67] incorporated Fixsen et al.’s recommendations regarding the importance of training in evidence-based practices through establishing i) program-based advocates, ii) providing adequate feedback and supervision, and iii) developing cost-effective approaches to training and coaching treatment providers. Suggestions from Carroll and Rounsaville [72] were also incorporated in one study [59] specifically in regards to the lack of effective program-based supervision in empirically supported treatments being one of the largest barriers to the implementation of these approaches in clinical practice. While only two studies were guided by Rogers’ [44, 48] argument that individuals are more likely to adopt an intervention after they have an increased knowledge about it and then develop a more favourable attitude towards it, eight (40%) adopted the notion that clinician factors may mitigate the relationship between fidelity to an intervention and patient outcomes [39, 42, 43, 46, 47, 54, 60, 62]. Clinician factors of interest included demographics (e.g. gender, age, experience, education; measured in all of the studies, although only sixteen (80%) reported an intention to evaluate these factors in relation to the implementation, [39, 42, 43, 46, 47, 50, 54, 59, 62, 65,66,67,68,69,70,71]), knowledge (3 studies, [67, 69, 70]) and attitudes (6 studies, [39, 43, 46, 54, 59, 65], e.g. beliefs about the origins of addictive behaviour, beliefs about evidence-based treatments (EBTs) or about the intervention itself; learning, confidence and commitment). Factors related to the context of the intervention were the focus of five studies [39, 43, 55, 59, 60], and included organisational factors, organisational readiness for change, and the importance of the context and multilevel approaches. Only two of these studies [55, 60] adopted Simpson’s [56] recommendations about “systemically-oriented” dissemination models, and the evaluation of these efforts in multiple domains, including organisational, clinician and client outcomes. However, two studies [39, 47] used a comprehensive implementation framework. One was entitled “Context-Tailored Training” [39], which is a method of training tailored to the unique challenges of a work setting and the other was the CFIR [47].

The remaining studies drew upon general research or theories that provided a rationale for the training strategies employed. For instance, some identified specific barriers to implementation such as the barrier of limited resources and the challenge of developing cost-effective approaches, (e.g. [5, 73, 74], others presented evidence for the potential uses of technology (e.g. [75])and two studies referenced psychological theories that inform approaches to learning (e.g. [76,77,78,79,80].

Consolidated framework for implementation research conceptual domains

As can be seen in Table 3, of the 36 subdomains of the CFIR, 32 were evaluated by included studies, although one study [39] mainly contributed to the breadth of coverage. Missing constructs included Intervention Characteristics related to evidence strength and quality, Outer Setting constructs including peer pressure and external policies and incentives, and the Inner Setting construct related to the relative priority of the implementation climate. While sixteen (80%, of studies) evaluated Characteristics of Individuals, less than half (9, 45%) measured Intervention Characteristics, and even fewer (4, 20%) measured Inner Setting constructs, with only one study [39] measuring Outer Setting constructs and the Process domain.

Implementation, service system and clinical factors evaluated

Almost all implementation outcome measures were concerned with fidelity to the intervention (17, 85%), although three studies measured knowledge [67, 69, 70], two studies measured self-efficacy [70, 81], two studies measured the cost of the intervention [61, 67], two studies measured adherence to the training [39, 55], one study measured supervision integrity [61], and one study measured adoption [47]. Predictors of implementation including clinician characteristics were measured by sixteen (80%) studies and clinician evaluation of the training was measured by four (20%) studies [39, 47, 50, 66]. The most frequently measured clinician characteristics were demographics (such as age, gender, ethnicity, education, experience, prior exposure to the intervention, counselling style or techniques, knowledge and attitudes towards evidence-based practices or the intervention itself, and recovery status). Predictors of implementation related to organisational level factors were measured by five studies [39, 47, 50, 54, 55], covering categories including acceptability, appropriateness, feasibility and penetration. Clinician evaluations of the training largely related to satisfaction with the format, methods, attributes and overall experience of the training, as well as the clinical utility of the training, and one question addressed any ideological conflict experienced. Further questions assessed clinicians’ views of the classroom environment (1) and cultural sensitivity of the training material (1).

Service system outcomes such as location, entry criteria, types of services offered, client to staff ratio, staff turnover, and record data quality, were measured by one study [50].

Clinical outcomes were measured by eight (40%) studies. Substance use was the most frequently measured outcome, followed by retention in treatment. Other clinical outcome measures included emotional and behavioural symptoms, change in motivation and treatment utilisation. In terms of patient characteristics, two studies measured age and gender [46, 71], one of which [71] also measured additional demographics, employment status, admission to the legal system, prior treatment and type of substance.

Effectiveness of implementation strategies

Outcome data by CFIR domain

Outcomes were reported for 9 of the 36 subdomains of the CFIR (see Table 3). Characteristics of Individuals including other personal attributes (7 sources, [39, 42, 43, 46, 50, 62, 65]), self-efficacy (5, [39, 43, 46, 50, 70]), and knowledge and beliefs about the intervention (3, [39, 66, 70]), was the domain with most outcome data. Outcome data also related to Intervention Characteristics including design quality and packaging (4 sources, [39, 50, 61, 66]), relative advantage (3, [39, 55, 66]) and cost (2, [61, 68]), and Inner Setting constructs including implementation learning climate (3 sources, [39, 50, 55]), culture (1, [50]) and structural characteristics (1, [54]). Due to the sparse coverage of outcome data relating to CFIR constructs, a more meaningful approach to reporting this information is to discuss the effectiveness of outcomes in relation to implementation factors and their relationships to primary, clinical and service system outcomes.

Strategies that effectively enhanced primary outcomes

Effective strategies have been summarised in Table 4. Of the seventeen studies with primary outcomes related to clinician fidelity to the intervention, fourteen achieved positive outcomes (70%), two involved strategies that were somewhat effective [61, 68], and one was not effective [54]. Three of the effective studies also found evidence for increases in clinician knowledge following the implementation [67, 69, 70], one of which found an increase in clinician self-efficacy [70]. A diverse range of methods, strategies and study designs are represented in this sub-group of studies. The majority (60%) evaluated discrete strategies such as the use of local experts trained to provide supervision [43, 59], financial incentives [45], theoretically grounded “booster sessions” [50], web-based training [69, 70], training or supervision via teleconferencing [42, 67], context based interventions [39, 55, 60] and workshop alone (for a brief intervention [46];). The remaining six studies achieving effective outcomes related to fidelity involved strategies with multiple approaches to training. Two of the studies in particular [43, 65] compared passive with active strategies and concluded that active approaches (such as participatory workshops, feedback and supervision) are more effective than passive strategies such as self-study [65] and workshops that provide didactic information only [68]. These conclusions are echoed by the four additional studies of multiple approaches, which included control group comparators. Each of the studies in this group concluded that passive approaches plus supervision are effective ([59, 62, 66, 71], and that coaching workshops [66] or local experts [59] can also add to the effectiveness of the implementation. One study involving multiple strategies and assessing implementation outcomes related to the adoption of the intervention [47] also found evidence for the effectiveness of passive plus active approaches to training. However, clinician factors were found to influence the effectiveness of the implementation over and above the presence of active and passive strategies [42, 43]).

Outcomes related to clinician characteristics were obtained by eight (40%) of studies and included background demographics, beliefs and attitudes, and learning. With regard to demographics, higher levels of education were associated with higher levels of motivational interviewing (MI) skills and were sustained over time [39], clinicians with no graduate degree experienced the greatest increase in MI spirit following the intervention [42], and clinicians with bachelor’s or master’s degrees were more competent initially but these differences were no longer evident by the end of the training [62]. Gender was found to predict adherence and competence by the end of training in integrated cognitive behavioural therapy (ICBT) [62], young men with male counsellors (and counsellors with more experience) were found to have better outcomes compared to controls [46], and female clinicians delivered contingency management (CM) more frequently at a trend level [47]. Results pertaining to the impact of clinicians’ beliefs and attitudes demonstrated that those with lower initial endorsement of disease belief models had higher levels of MI skills that were sustained at follow-up [39], that confidence was found to be associated with increased competence and adherence [43], that clinicians who viewed themselves as more effective in delivering the intervention and those having higher belief in the efficacy of the intervention also had clients with better outcomes [46], and the negative effect of higher Compatibility (i.e. the perception that the new practice aligns with one’s values, needs, and experiences) on CM adoption was attenuated by the training [47]. In terms of learning, clinicians with low average to average verbal abstract reasoning performances had higher MI Spirit following training than their counterparts [42], and aspects of “affective learning” related to empowerment or confidence were established and maintained following training [50].

At the organisational level, one study found that implementation strategies effectively increased the acceptability of the approach by engendering an openness to the new techniques [39]. More specifically, organisations who encouraged staff to do new things and had higher organisational self-efficacy also had clinicians with higher MI spirit, and agencies with greater openness to new techniques had clinicians who displayed a greater baseline to 3-month MI skill increase. Greater penetration was achieved in two studies [50, 55], which related to organisational decisions to implement the approach with fidelity [50] and an assessment of the programme environment as more controlled, greater clarity of programme expectations being communicated and patient reports of increased autonomy during the implementation [55]. Although one study found increased feasibility of an internet based training course within larger units, whilst training with a treatment manual was found to be more feasible in smaller agencies [54], another study found no relationship between the primary outcome and organisational size and makeup, patient retention or staff turnover [50].

Three studies of effective implementation strategies also conducted evaluations of the training. Clinicians’ appraisals of trainer competency and curriculum content, cultural sensitivity and classroom environment were very positive in one study [50], satisfaction with the training and its methods was high and there was a perceived utility about the intervention in a second study [66], and high satisfaction with the format, trainers and overall experience of training in a third study [39]. Evaluations of the relative costs of the intervention were conducted in two studies [61, 67].

Clinical outcomes

Positive patient-level outcomes were obtained by eight (40%) of studies. Specifically, a reduction in substance use was found following the implementation of Brief MI (BMI) workshops [46], a collaborative approach to multi-dimensional family therapy training (MDFT [55];), and the use of manual, workshop and supervision to train clinicians in Integrated CBT [62]. However, there was no change in substance use or treatment utilisation found in Martino et al.’s [61] study of a more cost-effective supervision approach to MI training. One study demonstrated an increase in patient retention following training (workshop and supervision for MI [71];), although the intervention had no significant impact on patient retention in two other studies (cost-effective supervision method [61]; booster sessions, [50]). Change in motivation was observed in patients treated by clinicians trained in motivational enhancement therapy (MET) following training with workshop, supervision and a local expert [59], and emotional and behavioural symptoms associated with problematic substance use decreased after receiving MDFT from clinicians trained via a collaborative approach [55].

Service system outcomes

There were no significant service system outcomes reported.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review of implementation studies in drug and alcohol settings for a range of evidence-based psychosocial approaches. A revealing finding of our review pertains to the lack of utilisation of implementation theories, models and frameworks in substance use specialty care, whereby only two studies used a comprehensive implementation framework [39, 47]. Given the plethora of frameworks, models and theories available (e.g. [11, 14]), the findings of this review suggest that implementation research has been underutilised as a potential guide for implementation research in drug and alcohol settings and substantiates the findings of other recent reviews demonstrating suboptimal use of implementation frameworks [13, 82].

Despite the underuse of implementation research in the development of strategies, there is a general recognition of the necessity of including active as well as passive strategies in SUD treatment research, which is supported by similar findings from both the health and mental health literature (e.g. [18, 83,84,85]). There are some exceptions to this trend, including studies that focused on the use of discrete strategies (e.g. supervision, booster sessions, technology) or on the influence of the context on implementation outcomes, but the reasoning behind these decisions was more to do with design factors rather than neglect of rigour or the importance of active approaches. While the particular strategies employed in the studies under review here are largely effective and reasonable, when viewed in the context of the CFIR domains, it is evident that several levels of influence are not addressed.

An analysis of results according to the CFIR domains and subdomains revealed that, although Characteristics of Individuals and to some extent Intervention Characteristics are given consideration, Inner Setting, Outer Setting and Process domains are largely neglected, and four subdomains are not assessed by any of the studies. Put simply, influences from within the organisation (e.g. team culture, leadership engagement, the implementation climate), external influences (e.g. patient needs and resources, organisational networks, external policies and incentives), and stages of the implementation process (e.g. planning, executing, reflecting and evaluating) are important aspects of the multi-level nature of implementing evidence-based practice and warrant further study in drug and alcohol settings. More recently, other implementation frameworks have been utilised more comprehensively to drive implementation strategy conceptualisation, strategies, measurement, and movement through phases of the implementation process that might address some of the gaps in the CFIR such as the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework [86]. The EPIS was used effectively to enhance service delivery amongst justice-involved youth accessing complex, multi-agency systems [14].

The literature suggests that clinician factors and (to a lesser extent) organisation level factors moderate the effectiveness of implementation over and above the presence of active and passive strategies. When implementing a training programme designed to upskill drug and alcohol clinicians in an evidence-based approach to practice, important factors to consider include certain demographics, clinician beliefs and attitudes, and modes of learning. Specifically, it may be important to modify training according to a clinician’s level of education (since highly educated clinicians may need a more challenging regime in order to make significant gains in proficiency) or verbal abstract reasoning performance (since those who are low on this trait may experience greater gains following the intervention), and to be aware of the influence that clinician gender and patient gender may have on the implementation outcome. It is also interesting that clinician beliefs and attitudes such as lower endorsement of disease belief models, higher confidence, more belief in one’s ability to deliver the intervention effectively, and higher belief in the efficacy of the intervention may moderate clinician fidelity to the intervention. Important organisational factors contributing to improved implementation outcomes might include organisational contexts in which staff are encouraged and supported to apply new practices, higher organisational self-efficacy, and greater openness to new techniques. It should also be noted that an overall strength of this implementation research into the transfer of evidence-based practices in drug and alcohol settings is the finding that three-quarters of the implementation strategies being evaluated were effective.

Limitations of this review surround the challenges of synthesising and comparing information derived from a diverse range of implementation strategies, clinical interventions, study conditions, and types of outcomes. For instance, drawing comparisons across studies that included discrete versus multi-modal strategies versus context-driven strategies, and across studies with different combinations of multi-modal strategies was problematic. Additionally, the fact that almost all studies were based in the US makes the review mainly applicable to that context. Outcomes were also mainly associated with clinician fidelity to the intervention, but were sometimes concerned with knowledge, self-efficacy, adoption and even supervisor fidelity. While the use of the EPOC data form, the conceptual model of Proctor [9] and the CFIR [11] assisted with teasing out these inconsistencies, they are still lacking empirical validation [87]. Lastly, our assessment of risk of bias and the inclusion of eligibility criteria that ensured only studies with rigorous designs became included in the review may have resulted in underreporting of findings related to CFIR domains due to space limitations (as mentioned by [35]) and the exclusion of studies that provide rich information about the implementation but have alternate designs. The exclusion of criminal justice settings might also be seen as a limitation in that certain studies seeking to integrate community-based care with justice settings may have been relevant.

Conclusion

This review contributes to the growing body of literature on the implementation of evidence-based practice in drug and alcohol settings, which may well have expanded since this review was conducted. It has demonstrated that particular strengths of the implementation research in these settings include the effectiveness of strategies employed, the broad recognition of the importance of understanding clinician characteristics and (to a lesser extent) intervention characteristics impacting the implementation outcomes. There is also some evidence for the mitigating effects of certain demographics, beliefs and attitudes, and modes of learning. On the other hand, this review has revealed that implementation frameworks have been underutilised and important levels of influence have been overlooked (e.g. organisational factors, external forces impacting the implementation, and an understanding of the effects of the process of the implementation). There is a need for determinant and process frameworks as well as integrating evaluation and outcomes frameworks in order to foster further development of approaches to improving implementation science in drug and alcohol service settings.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- USA:

-

United States of America

- MI:

-

Motivational interviewing

- CM:

-

Contingency management

- AA:

-

Alcoholics Anonymous

- NA:

-

Narcotics Anonymous

- TLFB:

-

Time line follow back

- PTSD:

-

Posttraumatic stress disorder

- CBT:

-

Cognitive behavioural therapy

- SUD:

-

Substance use disorder

- EBTs:

-

Evidence-based treatments

- EBPs:

-

Evidence-based practices

- TAU:

-

Treatment as usual

- SAMHSA:

-

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

- NIDA:

-

National Institute on Drug Abuse

- A-CRA:

-

The Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach

- P4P:

-

Pay for performance

- BMI:

-

Brief motivational interviewing

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial

- SSL:

-

Science to service laboratory

- PAS:

-

Provider attitudes scale

- ORCA:

-

Organisational Readiness to Change Assessment

- TC:

-

Therapeutic community

- MOC:

-

Managing organisational change

- DAT:

-

Drug abuse treatment

- TEACH-CBT:

-

Technology to Enhance Addiction Counselor Helping – Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

- MDFT:

-

Multi-dimensional family therapy

- MET:

-

Motivational enhancement therapy

- MIA:STEP:

-

Motivational Interviewing Assessment: Supervisory Tools for Enhancing Proficiency

- ICBT:

-

Integrated cognitive behavioural therapy

- IAC:

-

Individual addiction counselling

- TCS:

-

Tele-conferencing supervision

- WBT:

-

Web-based technology

References

Carroll KM. Dissemination of evidence-based practices: how far we've come, and how much further we’ve got to go. Addiction. 2012;107:1031–3.

Finney JW, Hagedorn HJ. Introduction to a special section on implementing evidence-based interventions for substance use disorders. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25:191–3.

Garner B. Research on the diffusion of evidence-based treatments within substance abuse treatment: A systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;36(4):376–99.

Saunders EC, Kim U, McGovers MP. Substance abuse treatment implementation research. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2014;44(1):1–3.

McLellan AT, Carise D, Kleber HD. Can the national addiction treatment infrastructure support the public's demand for quality care? J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;25(1):117.

Ducharme LJ, Mello HL, Roman PM, Knudsen HK, Johnson JA. Service delivery in substance abuse treatment: Reexamining “comprehensive” care. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2007;34(2):121–36.

Ferlie EB, Shortell SM. Improving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the United States: A framework for change. Milbank Q. 2001;79:281–315.

Lengnick-Hall R, Willging C, Hurlburt M, Fenwick K, Aarons GA. Contracting as a bridging factor linking outer and inner contexts during EBP implementation and sustainment: a prospective study across multiple US public sector service systems. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):1–16.

Proctor E, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, Mittman B. Implementation Research in Mental Health Services: an Emerging Science with Conceptual, Methodological, and Training challenges. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2009;36:24–34.

Klein KJ, Conn AB, Sorra JS. Implementing computerized technology: An organizational analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86:811–24.

Damschroder LJ, Hagedorn HJ. A Guiding Framework and Approach for Implementation Research in Substance Use Disorders Treatement. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25(2):194–205.

Whiteford HA, Dagenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Flaxman AD, Johns N, Burstein R, Murray CJ, Vos TV. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1575–86.

Moullin JC, Dickson KS, Stadnick NA, Rabin B, Aarons GA. Systematic review of the exploration, preparation, implementation, sustainment (EPIS) framework. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):1.

Becan JE, Bartkowski JP, Knight DK, Wiley TRA, DiClemente R, Ducharme L, et al. A Model for Rigorously Applying the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) Framework in the Design and Measurement of a Large Scale Collaborative Multi-Site Study. Health Justice. 2017;6(1):9.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50.

Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM, Wallace F. Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature; 2005.

Powell BJ, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, Carpenter CR, Griffer RT, Bunger AC, et al. A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Med Care Res Rev. 2012;69(2):123–57.

Powell BJ, Proctor EK, Glass JE. A Systematic Review of Strategies for Implementing Empirically Supported Mental Health Interventions. Res Soc Work Pract. 2014;24(2):192–212.

Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;10:53.

Ducharme LJ, Chandler RK, Harris AHS. Implementing Effective Substance Abuse Treatments in General Medical Settings: Mapping the Research Terrain. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;60:110–8.

Tancred T, Paparini S, Melendez-Torres GJ, Fletcher A, Thomas J, Campbell R, et al. Interventions integrating health and academic interventions to prevent substance use and violence: a systematic review and synthesis of process evaluations. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):227.

Champion K, Newton N, Barrett E, Teesson M. A systematic review of school-based alcohol and other drug prevention programs facilitated by computers or the internet. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013;32(2):115–23.

Deady M, Teesson M, Kay-Lambkin F. Treatments for co-occurring depression and substance use in young people: a systematic review. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2014;7(1):3–17.

Leske S, Harris M, Charlson F, Ferrari A, Baxter A, Logan J, et al. Systematic review of interventions for Indigenous adults with mental and substance use disorders in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States. Aust New Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50(11):1040–54.

Savic M, Best D, Manning V, Lubman DI. Strategies to facilitate integrated care for people with alcohol and other drug problems: a systematic review. Substance Abuse Treatment. Prevent Policy. 2017;12:19.

Hartzler B, Lash SJ, Roll JM. Contingency management in substance abuse treatment: A structured review of the evidence for its transportability. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;122:1–10.

Henderson J, Milligan K, Niccols A, Thabane L, Sword W, Smith A, et al. Reporting of feasibility factors in publications on integrated treatment programs for women with substance abuse issues and their children: a systematic review and analysis. Health Res Policy Syst. 2012;10:37.

Kelly P, Hegarty J, Barry J, Dyer K, Horgan A. A systematic review of the relationship between staff perceptions of organizational readiness to change and the process of innovation adoption in substance misuse treatment programs. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;80:6–25.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open Med. 2009;3(3):e123–30.

Louie E, Barrett EL, Baillie A, Haber P, Morley KC. Implementation of evidence-based practice for alcohol and substance use disorders: protocol for systematic review. Syst Rev. 2020;9:25.

Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012;50(3):217–26.

Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):21.

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Mental Health Serv Res. 2011;38(2):65–76.

CADTH. Grey Matters: a practical tool for searching health-related grey literature Internet. 2018 (cited 2019 Feb 22).

Williams EC, Johnson ML, Lapham GT, Caldeiro RM, Chew L, Fletcher GS, et al. Strategies to implement alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care settings: A structured literature review. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25(2):206–14.

Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An expanded Sourcebook 2ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage publications; 1994.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rogers M, et al. In: Research IfH, editor. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: A product from the ESRC Methods Programme. United Kingdom: Lancaster; 2006.

Bryman A. Social research methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001.

Baer JS, Wells EA, Rosengren DB, Hartxler B, Beadnell B, Dunn C. Agency context and tailored training in technology transfer: A pilot evaluation of motivational interviewing training for community counselors. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;37:191–202.

Rollnick S, Kinnersley P, Butler C. Context-bound communication skills training: Development of a new method. Med Educ. 2002;36:377–83.

Helfrich C, Li Y-F, Sharp N, Sales A. The Organizational Readiness to change Assessment (ORCA): Development of an instrument based on the Promoting action on Research in Health Services (PARIHS) framework. Implement Sci. 2009;4:38.

Carpenter KM, Cheng WY, SMith JL, Brooks AC, Amrhein PC, Wain RM, et al. “Old Dogs” and New Skills: How Clinician Characteristics Relate to Motivational Interviewing Skills Before, During, and After Training. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(4):560–73.

Decker SE, Martino S. Unintended Effects of Training on Clinicians' Interest, Confidence, and Commitment in Using Motivational Interviewing. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(3):681–7.

Rogers E. Diffusion of Innovations 5th ed. New York: Free Press; 2003.

Garner BR, Godley SH, Dennis ML, Hunter BD, Bair CML, Godley MD. Using Pay for Performance to Improve Treatment Implementation for Adolescent Substance Use Disorders. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:938–44.

Gaume J, Magill M, Longabaugh R, Bertholet N, Gmel G, Daeppen JB. Influence of Counselor Characteristics and Behaviors on the Efficacy of a Brief Motivational Intervention for Heavy Drinking in Young Men—A Randomized Controlled Trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(7):138–47.

Helseth SA, Janssen T, Scott K, Squires DD, Becker SJ. Training community-based treatment providers to implement contingency management for opioid addiction: time to and frequency of adoption. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;95:26–34.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th ed. New York: The Free Press; 1995.

Moore GC, Benbasat I. Development of an Instrument to Measure the Perceptions of Adopting an Information Technology Innovation. Information Systems Research. 1991;2(3):192–222.

Johnson KW, Young LC, Suresh G, Berbaum ML. Drug Abuse Treatment Training in Peru: A Social Policy Experiment. Eval Rev. 2002;26(5):480–519.

DeLeon G, Ziedenfuss T, James T Jr. Therapeutic communities for addictions. Springfield: Charles C Thomas; 1986.

Bickman L. Using program theory in evaluation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987.

Johnson KW, Bryant D, Collins DT, Noe D, Strader T, Berbaum M. Preventing and reducing alcohol and other drug use among high risk youths by increasing family resilency. Soc Work. 1998;43(4):297–308.

Larson MJ, Amodeo M, LoCastro JS, Muroff J, Smith L, Gerstenberger E. Randomized Trial of Web-based Training to Promote Counselor Use of CBT Skills in Client Sessions. Subst Abus. 2013;34(2):179–87.

Liddle HA, Rowe CL, Gonzalez A, Henderson CE, Dakof GA, Greenbaum PE. Changing Provider Practices, Program Environment, and Improving Outcomes by Transporting Multidimensional Family Therapy to an Adolescent Drug Treatment Setting. Am J Addict. 2010;15(1):102–12.

Simpson DD. A conceptual framework for transferring resarch to practice. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;22:171–82.

Moos R, Otto J. The Community-Oriented Programs Environment Scale: A methodolgy for the facilitation and evaluation of social change. Commun Ment Health J. 1972;8(1):28–37.

Achenbach TM. Child Behavior Checklist and related instruments. In: Maruish ME, editor. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcome assessment. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1994. p. 517–49.

Martino S, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Carroll KM. Community Program Therapist Adherence and Competence in Motivational Enhancement Therapy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96(1-2):37–48.

Martino S, Ball SA, Nich C, Canning-Ball M, Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM. Teaching Community Program Clinicians Motivational Interviewing Using Expert and Train-the-Trainer Strategies. Addiction. 2011;106(2):428–41.

Martino S, Paris M Jr, Añez L, Nich C, Canning-Ball M, Hunkele K, et al. The Effectiveness and Cost of Clinical Supervision for Motivational Interviewing: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;68:11–23.

Meier A, McGovern MP, Lambert-Harris C, McLeman B, Franklin A, Saunders EC, et al. Adherence and competence in two manual-guided therapies for co-occurring substance use and posttraumatic stress disorders: clinician factors and patient outcomes. Am J Drug Alochol Abuse. 2015;41(6):527–34.

Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, et al. The development of a Clinician- Administered PTSD Scale. J Trauma Stress. 1995;8:75–90.

Cacciola JS, Alterman AI, McLellan AT, Lin YT, Lynch KG. Initial evidence for the reliability and validity of a “Lite” version of the Addiction Severity Index. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:297–302.

Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, Martinez J, Pirritano M. A Randomized Trial of Methods to Help Clinicians Learn Motivational Interviewing. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(6):1050–62.

Morgenstern J, Morgan TJ, McCrady BS, Keller DS, Carroll KM. Manual-guided cognitive-bahavioral therapy training: a promising method for disseminating empirically supported substance abuse treatments to the practice community. Psychol Addict Behav. 2001;15(2):83–8.

Rawson RA, Rataemane S, Rataemane L, Ntlhe N, Fox RS, McCuller J, et al. Dissemination and Implementation of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Stimulant Dependence: A Randomized Trial Comparison of Three Approaches. Subst Abus. 2013;34(2):108–17.

Smith JL, Carpenter KM, Amrhein PC, Brooks AC, Levin D, Schreiber EA, et al. Training Substance Abuse Clinicians in Motivational Interviewing Using Live Supervision Via Teleconferencing. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(3):450–64.

Weingardt KR, Villafranca SW, Levin C. Technology-Based Training in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Substance Abuse Counselors. Subst Abus. 2006;27(3):19–25.

Weingardt KR, Cucciare MA, Bellotti C, Lai W-P. A Randomized Trial Comparing Two Models of Web-Based Training in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Substance Abuse Counselors. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;37(3):219–27.

Carroll KM, Ball SA, Nich C, Martino S, Frankforter TL, Farentinos C, et al. Motivational interviewing to improve treatment engagement and outcome in individuals seeking treatment for substance abuse: A multisite effectiveness study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81:301–12.

Carroll K, Rounsaville B. A vision of the next generation of behavioral therapies research in the addictions. Addiction. 2007;102:850–62.

Joe G, Broome K, Simpson D, Rowan-Szal G. Counselor perceptions of organizational factors and innovations training experience. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;33(2):171–82.

Simpson D, Joe G, Rowan-Szal G. Linking the elements of change: Program and client responses to innovation. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;33(2):201–9.

Wutoh R, Boren S, Balas E. eLearning: A re- view of internet based continuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2004;24:20–30.

Balcazar F, Balcazar F, Hopkins BL, Suarez Y. A critical, objective review of performance feedback. J Organ Behav Manag. 1986;7:65–89.

Kivlighan D Jr, Angelone E, Swafford K. Live supervision in individual psychotherapy: Effects on therapist’s intention use and client’s evaluation of session and working alliance. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 1991;22:489–95.

Donovan J, Radosevich D. A meta-analytic review of the distribution of practice effect: Now you see it, now you don’t. J Appl Psychol. 1999;84:795–805.

Prescott P, Opheim A, Bortveit T. The effect of workshops and training on counseling skills. Tidsskrift Norsk Psykologforening. 2002;39:426–31.

Skinner B. Science of human behavior. New York: Free Press; 1953.

Morgenstern J, Morgan TJ, McCrady BS, Keller DS, Carroll KM. Manual-Guided Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy Trianing: A promising Method for Disseminating Empirically Supported Substance Abuse Treatments to the Practice Community. Psychol Addict Behav. 2001;15(2):83–8.

Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implementation Sci. 2013;8:1.

Beidas R, Kendall P. Training therapists in evidence-based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2010;17(1):1–30.

Davis D, Davis N. Educational interventions. In: Straus S, Tetroe J, Graham I, editors. Knowledge translation in health care: Moving from evidence to practice. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. p. 113–23.

Herschell A, Kolko D, Baumann B, Davis A. The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: A review and critique with recommendations. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:448–66.

Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Adm Policy Mental Health Serv Res. 2011;38(1):4–23.

Grol R, Bosch M, Hulscher M, Eccles M, Wensing P. Planning and studying improvement in patient care: The use of theoretical perspectives. Milbank Q. 2007;85(1):93–138.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by the NSW Ministry of Health under the NSW Translational Early-Mid Career Fellowship Scheme (KM and EB), a Research Training Program Scholarship (EL), a NSW Translational Health Research Grant Scheme (KM, PH, AB) and a NHMRC Practitioner Fellowship (PH). The contents are solely the responsibility of the individual authors and do not reflect the views of NSW Ministry of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EL and KM conceptualised, lead and designed this study. EL and EB performed study selection and quality assessment. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and when necessary third party adjudication (KM). AB and PH provided methodological consultation. The remaining authors all assisted with the study design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

PRISMA Checklist. Checklist of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P).

Additional file 2.

Example Study Search. Details of concepts and search terms used in MEDLINE.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Louie, E., Barrett, E.L., Baillie, A. et al. A systematic review of evidence-based practice implementation in drug and alcohol settings: applying the consolidated framework for implementation research framework. Implementation Sci 16, 22 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-021-01090-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-021-01090-7