Abstract

Background

Implementation science seeks to promote the uptake of research and other evidence-based findings into practice, but for healthcare professionals, this is complex as practice draws on, in addition to scientific principles, rules of thumb and a store of practical wisdom acquired from a range of informational and experiential sources. The aims of this review were to identify sources of information and professional experiences encountered by healthcare workers and from this to build a classification system, for use in future observational studies, that describes influences on how healthcare professionals acquire and use information in their clinical practice.

Methods

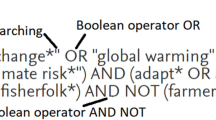

This was a mixed studies systematic review of observational studies. DATA SOURCES: OVID MEDLINE and Embase and Google Scholar were searched using terms around information, knowledge or evidence and sharing, searching and utilisation combined with terms relating to healthcare groups. ELIGIBILITY: Studies were eligible if one of the intentions was to identify information or experiential encounters by healthcare workers. DATA EXTRACTION: Data was extracted by one author after piloting with another. STUDY APPRAISAL: Studies were assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). PRIMARY OUTCOME: The primary outcome extracted was the information source or professional experience encounter. ANALYSIS: Similar encounters were grouped together as single constructs. Our synthesis involved a mixed approach using the top-down logic of the Bliss Bibliographic Classification System (BC2) to generate classification categories and a bottom-up approach to develop descriptive codes (or “facets”) for each category, from the data. The generic terms of BC2 were customised by an iterative process of thematic content analysis. Facets were developed by using available theory and keeping in mind the pragmatic end use of the classification.

Results

Eighty studies were included from which 178 discreet knowledge encounters were extracted. Six classification categories were developed: what information or experience was encountered; how was the information or experience encountered; what was the mode of encounter; from whom did the information originate or with whom was the experience; how many participants were there; and where did the encounter take place. For each of these categories, relevant descriptive facets were identified.

Conclusions

We have sought to identify and classify all knowledge encounters, and we have developed a faceted description of key categories which will support richer descriptions and interrogations of knowledge encounters in healthcare research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Implementation science and clinical practice

Well-evidenced interventions intended to improve patient well-being may not be used optimally across healthcare professions [1–8] with many barriers identified to the uptake of best evidence [5, 6, 9–12] and interventions designed to overcome these [13–15]. Implementation science seeks to promote the uptake of research and other evidence-based findings into practice [16], but for healthcare professionals, this is complex as practice draws on, in addition to scientific principles, rules of thumb and a store of practical wisdom [17] acquired from a range of informational and experiential sources. Gabbay and Le May’s ethnographic study of how primary care clinicians build mindlines—“collectively reinforced, internalised, tacit guidelines”—found it was rare that medical practitioners searched for guidelines [18, 19]. Instead, clinicians drew on multiple sources of information and experiences as they cared for patients. Much of the knowledge they acquired was tacit, i.e. it could not be put into words [20], as, for example, when someone tries to convey to another exactly how not to fall off a bike when riding. The knowledge is embodied. We know how to cycle and yet cannot fully explain it. So, rather than conceiving of a single knowable reality, mindlines are based on a more “fluid, embodied and intersubjective view of knowledge” that accommodates context and multiple realities [21]. In this way, the knowledge of the practitioner is in the moment and in their practice (or “knowledge-in-practice”) in a particular context of space and time (“knowledge-in-practice-in-context”) [18]. Implementation science, with its aspiration to change practice, could benefit from a richer understanding of how the complex, personal and context-laden phenomenon of knowledge-in-practice develops over time.

Existing reviews of information sources used by clinicians

A number of reviews have sought to collate the sources of information clinicians use and the ways in which they seek them [22–28]. These include the information sources used by rural health professionals [27], nurses [25], physicians [22, 23, 28] and dentists in developed countries [24]. The reviews found that colleagues were often ranked as primary information sources and that learning informally was widespread. However, none of them attempted to synthesise the research from across healthcare groups, and none attempted to classify the context and other attributes of healthcare professionals’ interactions with information or experiences. Thus, implementation research is not yet able to explore what characteristics are associated with the information and experiential encounters that matter to healthcare professionals.

Defining “knowledge encounters”

Our prior reading suggested that in order to describe the breadth of occasions when clinicians come across phenomena that have the potential to change their knowledge, the more familiar terms in the literature around knowledge transfer, translation, exchange and sharing would not be sufficient. They could not account for the unplanned way in which the mindlines work suggested healthcare professionals developed their knowledge-in-practice. We found “encounter” to be a broad enough term to help describe these occasions as it may be expected or unexpected, brief or protracted, experiential and involve a degree of “dealing with” something or someone [29–31].

Many definitions of knowledge exist but we adhered to an interpretivist perspective of knowledge as discussed above in the context of mindlines and knowledge-in-practice-in-context. Working from Stenmark [32], we conceive of information as a means (e.g. written, oral, performative) of attempting to articulate an individual’s knowledge, but it lacks the personal, tacit, understanding that the individual has of the particular phenomenon they describe. Experiential knowledge, on the other hand, is that knowledge gained through observations in routine practice, for example, of what does and does not “work” [33] and is often followed by a period of sense-making [34]. Information, from Stenmark’s perspective, may alter another individual’s prior knowledge but is not in itself knowledge.

We therefore defined a knowledge encounter as a circumstance in which an individual interacts with information or an experience that has the potential to influence their knowledge-in-practice. Knowledge here, therefore, is the potential for knowledge to change in response to the information or experience, rather than being an encounter with knowledge.

Aims

The aims of this review were the following:

-

To identify the sources of information and professional experiences (referred throughout this article simply as “experiences”) encountered by healthcare workers that could influence their knowledge-in-practice and the contexts within which they are encountered

-

To build a classification system, for use in future observational studies, that describes influences on how healthcare professionals acquire and use information in their clinical practice

Methods

Identification of studies

A systematic mixed studies review was conducted to identify the information sources and experiences that health professionals reportedly encounter. “Mixed studies reviews” include quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods studies to provide a more holistic view of a given problem [35, 36].

Study designs

Observational studies in English or German that sought to identify sources of information and experiences, and the ways in which these were encountered, were eligible. Studies that only explored a narrowly restricted source, e.g. internet, were excluded. Experimental study designs were excluded because we were interested in gathering data from existing practice rather than a modified one.

Participants

All healthcare professionals responsible for patient (including animal) care were eligible. Studies involving a majority of undergraduate students were not eligible. We defined as eligible healthcare professionals any clinical professional that fell within the MEDLINE MeSH term “Health Occupations”. This includes: allied health occupations (e.g. occupational therapy), chiropractors, dentists, medical doctors, nurses, optometrists, podiatrists and veterinary practitioners. We included all of these, including veterinary practitioners, because we felt that whilst there are differences in the contexts within which information or experiences are encountered, the underlying process of professional learning and development are sufficiently similar across professional settings.

Outcomes

Any information source or experience related to patient care (this includes the care of animals in the case of veterinarians) was eligible.

Electronic databases and search engines

The following databases and search engines were searched: OVID MEDLINE, OVID Embase, and Google Scholar. Embase was searched from the first records in 1974 to June 6, 2014. Medline was searched from 1946 to week 4 of May 2014 using terms relating to information, knowledge or evidence and sharing, searching and utilisation combined with terms relating to the various healthcare groups. [For search strategy, see Additional file 1]. The final search was conducted on February 6, 2014. Google Scholar was searched using the combinations of “sources of knowledge” and healthcare groups. The searches were run again on July 29, 2016, to identify studies that included any information or knowledge sources not identified in the studies from the original search.

Reference lists and citation searches

We carried out backward citation searches for all included studies in Google Scholar and forward and backward citation searches in Web of Science for the more comprehensive studies [19, 33, 37] and 10 systematic reviews [22, 23, 25–28, 38–41]. Bibliographies and reference lists were checked for potentially relevant studies’ books on implementation science and evidence-based healthcare in the authors’ personal collections.

Combining search results and identifying eligible studies

Potentially eligible studies were identified from the databases and Google Scholar searches, exported to EndNote X6 and duplicates removed.

Titles and abstracts of all studies were screened for potential inclusion in the review by one author (DH). Where a study was potentially eligible, the full text was retrieved and the final decision on eligibility made by DH.

Data extraction

A purpose designed data extraction form was used to extract data from eligible studies. This was piloted by DH and SM. The final data extraction was completed by DH. From eligible studies, the following were extracted: Author; contact details; citation; year; study design; whether study was reliant on recall, real-time data collection or both; instrument/tool/method used and, in the case of quantitative instruments such as questionnaires, the status regarding validation and reliability; study period if longitudinal; participant description (number of participants, healthcare profession); setting—primary, secondary or tertiary; sources of knowledge; themes or categories used/developed by the authors; types of knowledge considered, i.e. tacit, explicit or both; and references of potentially relevant studies or reviews.

The sources of information or experiences were collated in a spreadsheet by DH. Where descriptions of sources were different but shared the same meaning, these were grouped together by DH as a single construct.

The quality of the included studies was evaluated using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [36, 42].

Analysis

Our preliminary reading of the literature suggested that information sources and experiences, and the way they are encountered, are multifaceted and would benefit from a classification system that could accommodate this. Kwasnik states that “classification is the meaningful clustering of experience” and argued that the way we classify knowledge can assist in discovery of new knowledge [43]. Our intention is that the classification system we develop would help to organise the experience healthcare workers have of encountering new information and experiences and, therefore, assist with the discovery of new methods for implementation science.

We chose to adopt the facet classification approach to describe the important contexts within which information and experiences are encountered because facet classifications recognise that there is more than one way to view the world and that facets themselves are flexible to accommodate new phenomena over time [43]. This approach has been used to classify information on the World Wide Web [44] and in information-seeking tasks [45]. An example of a facet classification is the way we classify wines using the categories of country (France, Germany, Australia, Chile, etc.), grape variety (chardonnay, cabernet, merlot, etc.), alcohol content (0% through 15%) and colour (white, red, rosé).

To describe and organise the experiential and information sources, we adapted the Bliss Bibliographic Classification System, known as BC2. This system classifies, for any piece of knowledge, what is being done, what are its parts or properties, how is this achieved, by what means and by whom, where, and when? [46] and was developed from the work of Ranganathan who identified repeating elements of all subjects: personality, matter, energy, space and time [47].

After extracting the data, we developed a classification of knowledge encounters together with a description of facets that described key elements of information and experiential knowledge sources that healthcare workers encountered. We used a constant comparative method with extensive discussion between the authors as the classification was refined.

Our synthesis involved a mixed approach using the top-down logic of the BC2 classification to generate thematic categories and a bottom-up approach to develop facets (or codes) for each category from the data. That is, we altered, added or removed the specific terms used in the BC2 classification, for example from “What is being done” to “What information or experience is encountered”. We then read and re-read the extracted sources, using the constant comparison technique to develop descriptive codes. As an example, when an article reported “colleagues via internet”, we recognised that “someone” was involved in the encounter. Similarly, someone was involved in an article that reported “mentor” and another that included “patients’ experiences of illness”. Thus, we created a category to describe someone from whom a healthcare worker might have obtained information in their knowledge encounter. We called that category “from whom did the information originate or with whom was the experience”, to fit the BC2 logic. Then we re-read our data to generate facets for each category. The facets were higher level descriptive codes of the people involved in the encounter. For example, from the following raw data, we created the facet “practitioner”: “peers”, “observation of others’ practice”, “formalised supervision”, “systematic self-evaluation”, “specialist” and “email contact with specialist”. In a similar way, the facets of “Non-practitioner (colleague)”, “Patient”, “Researcher”, “Educator”, “Regulator”, “Employer” and “Salesperson” were generated.

Results

Study characteristics

Nine thousand one hundred thirty-eight potentially eligible reports were screened by title and abstract. Of these, 113 were potentially eligible, and therefore, the full text was retrieved. 37 of these were not eligible. 76 studies were eligible for inclusion in the review from the 2014 search [19, 33, 37, 48–120]. The additional search in 2016 identified a further 4 eligible studies [121–124]. Their data are included in the analysis for completeness but they did not identify any additional descriptions of knowledge encounters and did not, therefore, affect the classification (see Fig. 1).

Four studies used a mixed methods design (interviews and surveys), 22 used qualitative methods (ethnography, case study, vignettes, interviews, focus groups or qualitative questionnaire) and 54 used quantitative methods (survey, observation, critical incident technique or interviews). Of the 80 studies, only 24 allowed for the inclusion of knowledge encounters that were experiential or tacit.

Seventy-one of the studies included a single group of healthcare professionals, and 9 involved two or more healthcare groups. Across the studies as a whole, the quality was evaluated by MMAT as moderate or low quality. The study characteristics are summarised in Table 1. [Please see Additional file 2 for details of individual studies].

Development of a classification of knowledge encounters

One hundred seventy-eight individual descriptions of encounters with information sources or experiences were identified across the 80 studies (see Additional file 3). Some of these were described simply as nouns, e.g. journal, but there is an implicit requirement for a verb, i.e. to read a journal. On other occasions, the verb was recorded, e.g. informal conversation with colleagues. Thus, what authors described as “sources” were often “encounters with sources” and might be intentional or unintentional.

We modified the BC2 classification to add categories where differentiation was required and remove redundancies. In summary, the classification we developed included the following six key questions about the knowledge encounter (short versions used in Fig. 2 are in brackets):

-

What information or experience was encountered (“What information or experience?”)?

-

How was the information or experience encountered (“How?”)?

-

What was the mode of encounter (What mode?)?

-

From whom did the information originate or with whom was the experience (“From / with whom?”)?

-

How many participants were there (“How many?”)?

-

Where did the encounter take place (“Where”)?

We removed the BC2 categories “what are its [the knowledge’s] parts or properties” and “when”.

Facets of categories

Whilst multiple facets were recognised in the literature, we have organised them to describe the important components of the six key classification questions just identified.

What information or experience was encountered?

This category reflected the knowledge that the information attempted to articulate, or experiential knowledge. We reviewed existing models of knowledge (see the “Discussion” section) to help construct the facets of this category (Table 2).

How was the information or experience encountered?

It was evident from the data that senses such as smell and touch were used by healthcare professionals as they encountered sources of knowledge, in addition to seeing and hearing. Additionally, there were clearly internal, i.e. non-sensory means of encountering knowledge such as reflecting on one’s experience (Table 3).

What was the mode of the encounter?

It was evident that some encounters took place in person and some remotely or through a medium. Where the encounter was not in person, electronic means were dominant ways of bridging the gap.

Technology would be used in many settings to augment the sharing of information, for example at a conference, but the distinction here has more to do with whether the individual is present in person rather than using a medium to communicate (Table 4).

From whom did the information originate or with whom was the experience?

Our thematic organisation of the people from whom information originated or with whom there was an experience resulted in eight facets (Table 5). Whilst in this table the facets are individual, we conceive of the terms being used in the plural too, e.g. “salesperson” as the facet for the source “pharmaceutical/product literature”.

How many participants were there?

In addition to determining the role of the individual or organisation involved in sharing the information, it was evident that some of the encounters with sources might involve an individual alone, with one or two others, or as part of a larger group. Social learning is believed to be an important element of how individuals acquire new knowledge, particularly in practice [125–127], and therefore, we felt that this facet of a knowledge encounter was an important one to capture (Table 6).

Where did the encounter take place?

For this category, we tried to distil from the sources identified a sense of place in which the knowledge encounter could occur. The setting was in part determined by the intention, e.g. whether a meeting was intended to be an educational event or if it was intended to be social but where new information was encountered nonetheless (Table 7).

We have summarised the categories and facets in Fig. 2.

Discussion

We have conducted a systematic mixed studies review to identify all encounters with information and experiences reported in the healthcare literature and identified 80 qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies that reported on such encounters. We have then developed a faceted classification to describe what we term knowledge encounters using a mixed didactic-inductive process. The classification has six categories that describe different aspects of any encounter: what information or experience was encountered, how the information or experience was encountered, what the mode of encounter was, from whom did the information originate or with whom was the experience, how many participants there were, and where the encounter took place. Each category is described by key facets that enable a deeper understanding of the actual knowledge encounter.

Discussion of the generation of facets

Higgs and Titchen [128] describe three knowledge types in professional practice: theoretical or scientific knowledge, craft knowledge and personal knowledge. Similarly, Kemmis proposes that there is public knowledge (theoretical, scientific), action (as an object of knowing or thought) and practice (theory) [127]. Eraut divides knowledge into codified (also known as public or propositional knowledge) and personal [129]. Gabbay and Le May identified six knowledge types from their work with healthcare providers over many years. These knowledge types were experiential, research, theoretical, policy, custom and practice and trial and error [18, p 109]. We drew on all of these in developing the classification, but in practice, we found at times that we were unable to determine whether, or how much, knowledge encounters were with each facet we described. For example, Guidelines are known to incorporate both research and the developers’ expertise. Further, a reader of a textbook might be unaware what was based on empirical research, what on theory and what on the personal experiences of the authors. Whilst it might be evident that there are these distinctions in some cases (e.g. when reading a research article in a journal or an evidence summary), we adopted the common denominator of “codified knowledge”.

One source of information that arose from the data was that produced by commercial companies, often for the purpose of marketing. It is not clear whether this has been subjected to quality control in the sense of codified knowledge. We therefore included an additional category of “product or service knowledge” though we acknowledge that there may be occasions when the product knowledge truly reflects codified knowledge, i.e. when it is based on peer-reviewed research.

There were multiple roles individuals or organisations could be envisaged to perform depending on the context of the encounter. From a relational perspective, a “colleague” might be someone whose “practice is observed” or with whom an “informal conversation” is had. Colleagues might take on the role of an educator or as a “mentor” or “peer opinion leader”. They might also be an employer and responsible for creating “locally developed guidelines”. In many cases, it was not possible for us to define the role due to lack of contextual information, but there were sufficient examples of different roles across the included studies for us to develop a number of facets to describe the various roles others play in knowledge encounters.

Given that an individual can perform several different roles, we defined this category according to the primary role taken by the individual(s) or organisation at the moment of information or knowledge encounter. Thus, a “journal club” may be dependent on the interpretations of fellow practitioners, whilst the reading of a research article in a “journal” alone would entail the source being a researcher.

There was a challenge in how to classify non-human sources such as journal articles and “video”. We determined that the primary role of the individual(s) or organisations creating the particular information source would follow the same categories as for the in-person encounters. Thus, a research article may be written by a researcher who might write another article that explains a clinical technique as an educator. The descriptive facets for this category can be seen in Table 5.

These facets could equally be ascribed to the self or to other colleagues. In such a case, personal reflection by a healthcare professional on their practice would be described by the facet “practitioner”.

Preliminary testing of the classification with dentists

The faceted classification developed here is a complex one. We want to test its feasibility in future studies. We created a series of five scenarios based on a composite of the sources extracted for this review, for dentists to work through, with a description of what was intended by the different facets [130]. Each scenario used a mixture of photos and text of a dentist encountering information or experiential knowledge. After brief training on the use of the classification, four dentists working in general dental practice independently classified the 5 scenarios according to the type of knowledge encounter. There was good agreement (75–100%) for all but the “setting” category in two of the scenarios, when there was 50% agreement. The dentists fed back that this tool was straightforward to use once they had undergone the training.

Limitations

There are a number of potential limitations associated with this review.

The search for studies used a combination of formal search strategy and citation searching. It is possible that we have missed potentially relevant studies because authors have used terms we did not include in the search strategy and because we confined the eligible studies to English. However, as we were not seeking to quantify the encounters with knowledge sources, we feel that we reached a saturation of both classifications of knowledge encounters and descriptions of their key facets in the studies we did identify.

The screening of titles and abstracts was conducted by a single reviewer. This increases the possibility that potentially eligible studies were not included. Similarly, it is a limitation that the coding and design of the classification were done by one author.

The discreet facets identified may not reflect all the facets that a particular knowledge encounter may include. Thus, users of the classification will have to make a choice about which facet is most appropriate of all those that could be used.

We have also identified limitations of the studies included. The literature on knowledge sources identified here has been largely dependent on recall of exposure to different sources. Apart from three studies that used brief periods (4 h or half a day) of observation [53, 77, 101], all of the quantitative data has depended on recall. This review was not concerned with quantifying the proportion of encounters ascribed to each source, but due to the impact of recall bias [131], we may not have a complete picture of sources of information encountered by healthcare professionals. In the qualitative studies, much more contextual information was given to understand what the encounter with a particular source meant to the clinician. Finally, several of the closed question surveys we identified appeared not to follow a particular theoretical structure, and we were unable to identify one that had all of the knowledge source encounters identified in this review.

We used the MMAT to assess the quality of the studies. We value the attempt by the authors of MMAT to provide a means for evaluating and comparing the quality of different study designs when conducting mixed studies reviews. However, whilst it was apparently straightforward to use with individual studies, we found that we were unsure what the results meant when compared, in particular, to studies conducted within different research paradigms where “quality” can mean something very different [132].

Implications for implementation science

There is a growing body of evidence to support the assertion that healthcare professionals’ knowledge-in-practice—the knowledge that is used as they practice—is influenced by interactions with a variety of formal and informal sources of information and experience. However, as shown in this review, there has been relatively little real-time empirical study of the ways in which this happens. We think that by studying the ways in which healthcare professionals’ knowledge-in-practice is influenced by what they encounter and how they encounter it, we can begin to better understand how to work with the grain of practice to develop systematic approaches to contribute to achieving implementation science’s aspiration of promoting the uptake of research and other evidence-based findings into practice [16].

From their ethnographic work in general medical practices, Gabbay and Le May coined the term mindlines to describe the internal, personal, tacit guidance medical practitioners used as they went about their practice. Mindlines develop as healthcare professionals interact with, and make sense of, multiple sources of information and experiences. Recognising that quantitative methods can rarely develop the rich understanding of individual practices that ethnographic methods can, we nonetheless think that the classification described here will allow for longitudinal survey tools to be developed that capture rich contextual data of how healthcare professionals develop their knowledge-in-practice in a variety of contexts.

With the increasing availability and functionality of digital means to record experiences in real time [133], there is an opportunity to study larger numbers of healthcare professionals in any number of settings as they go about their lives. Observational methods are limited not only by the large amount of time needed and ability for a researcher to be in only one place at a time but also by restrictions of access to, for example, peoples’ homes and social gatherings where knowledge encounters are bound to occur. Real-time data capture has been used to study a wide range of health and social topics [134–137], and we envisage research that explores knowledge encounters in a similar way. This could be done qualitatively, with participants recording in their own words their experience of the encounter. However, by using a classification to describe the knowledge encounters, participants may be able to record encounters more quickly and record key characteristics of the encounter. Meanwhile, researchers would be able to gather larger quantities of data and analyse it much more quickly. Through a better understanding of what, how, where and with whom information and experiences diffuse into practice, it is hoped that we can develop new implementation approaches to promote research uptake alongside other information and experience as healthcare professionals develop their knowledge-in-practice.

Further, development of this longitudinal approach could explore whether, and how, particular facets of knowledge encounters are associated with changes in knowledge-in-practice and how these facets change, for example as healthcare professionals mature. Implementation researchers might then develop interventions that leverage off these facets to help improve uptake of evidence-based practices. For example, if knowledge encounters that share the facets of individualised codified knowledge, verbal, non-electronic, with practitioners, in social settings and occur in groups are associated with more change in knowledge-in-practice, can we adopt, adapt or design new opportunities for professionals to experience knowledge encounters with research based on these, rather than on facets not associated with changes in knowledge-in-practice?

Finally, whilst classifications function as descriptive and explanatory frameworks for ideas or phenomena, they also act like theories do in providing the basis for the generation and testing of new ideas [138]. We think that by describing what is a complex phenomenon using a faceted classification, implementation researchers may find new ways of thinking about knowledge-in-practice and how to work effectively with it to promote the use of research and other evidence-based findings in practice.

Conclusions

Healthcare professionals encounter information and experiences that may change their knowledge of patient care in many different ways. We have developed a classification to organise and describe the complexity of how healthcare professionals encounter information and experiences. We have identified six key classifying questions to understand the context in which information and experiences are encountered and described important facets for each of these. This novel faceted classification for knowledge encounters has been developed as a tool for future observational studies of healthcare professionals. Future research should explore how this classification of knowledge encounters can deepen our understanding of how healthcare professionals learn and develop their knowledge-in-practice. Over time, we want to be able to facilitate knowledge encounters that improve the uptake of evidence-based practices in healthcare.

Abbreviations

- BC2:

-

Bliss Bibliographic Classification

- MMAT:

-

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool

References

Heneghan C, Perera R, Mant D, Glasziou P. Hypertension guideline recommendations in general practice: awareness, agreement, adoption, and adherence. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(545):948–52.

Bonetti DL. Evidence not practised: the underutilisation of preventive fissure sealants. Br Dent J. 2014;216(7):409–13.

Tellez M, Gray SL, Gray S, Lim S, Ismail AI. Sealants and dental caries: dentists’ perspectives on evidence-based recommendations. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142(9):1033–40.

Bansal R, Bolin KA, Abdellatif HM, Shulman JD. Knowledge, attitude and use of fluorides among dentists in Texas. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2012;13(3):371–5.

Bhattacharyya N, Kepnes LJ. Patterns of care before and after the adult sinusitis clinical practice guideline. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(7):1588–91.

Pathman DE, Konrad TR, Freed GL, Freeman VA, Koch GG. The awareness-to-adherence model of the steps to clinical guideline compliance: the case of pediatric vaccine recommendations. Med Care. 1996;34(9):873–89.

Perkins RB, Anderson BL, Gorin SS, Schulkin JA. Challenges in cervical cancer prevention: a survey of US obstetrician-gynecologists. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(2):175–81.

Widyahening IS, van der Graaf Y, Soewondo P, Glasziou P, van der Heijden GJ. Awareness, agreement, adoption and adherence to type 2 diabetes mellitus guidelines: a survey of Indonesian primary care physicians. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15(1):1.

Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458–65.

Grol R, Wensing M. What drives change? Barriers to and incentives for achieving evidence-based practice. Med J Aust. 2004;180(6 Suppl):S57–60.

Zwolsman S, te Pas E, Hooft L, Wieringa-de Waard M, van Dijk N. Barriers to GPs’ use of evidence-based medicine: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62(600):e511–21.

van Dijk N, Hooft L, Wieringa-de WM. What are the barriers to residents’ practicing evidence-based medicine? A systematic review. Acad Med. 2010;85(7):1163–70.

Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Gillies C, Shaw EJ, Cheater F, Flottorp S, et al. Tailored interventions to address determinants of practice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD005470.

Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Young JM, Odgaard-Jensen J, French SD, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6:CD000259.

O'Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, Oxman AD, Odgaard-Jensen J, Kristoffersen DT, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:CD000409.

Eccles MP, Mittman BS. Welcome to implementation science. Implement Sci. 2006;1(1):1.

Hunter KM. A science of individuals: medicine and casuistry. J Med Philos. 1989;14(2):193–212.

Gabbay J, Le May Ae. Practice-based evidence for healthcare : clinical mindlines. Abingdon: Routledge; 2011

Gabbay J, le May A. Evidence based guidelines or collectively constructed “mindlines?” Ethnographic study of knowledge management in primary care. BMJ. 2004;329(7473):1013.

Polanyi M, Sen A. The tacit dimension. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press; 2009. p. xix, 108.

Wieringa S, Greenhalgh T. 10 years of mindlines: a systematic review and commentary. Implement Sci. 2015;10:45.

Davies K. The information-seeking behaviour of doctors: a review of the evidence. Health Info Libr J. 2007;24(2):78–94.

Dawes M, Sampson U. Knowledge management in clinical practice: a systematic review of information seeking behavior in physicians. Int J Med Inform. 2003;71(1):9–15.

Isham A, Bettiol S, Hoang H, Crocombe L. A systematic literature review of the information-seeking behavior of dentists in developed countries. J Dent Educ. 2016;80(5):569–77.

Spenceley SM, O'Leary KA, Chizawsky LLK, Ross AJ, Estabrooks CA. Sources of information used by nurses to inform practice: an integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45(6):954–70.

Osiobe SA. Use of information resources by health professionals: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 1985;21(9):965–73.

Dorsch JL. Information needs of rural health professionals: a review of the literature. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000;88(4):346–54.

Coumou HC, Meijman FJ. How do primary care physicians seek answers to clinical questions? A literature review. J Med Libr Assoc. 2006;94(1):55–60.

Oxford Dictionaries. Encounter 2015 [cited 2015. Available from: http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/encounter]. Accessed 12 Mar 2017.

Random House Inc. Encounter. 2015. [Available from: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/encounter]. Accessed 12 Mar 2017.

Merriam-Webster. Encounter. 2015. [Available from: http://www.learnersdictionary.com/definition/encounter]. Accessed 12 Mar 2017.

Stenmark D. The relationship between information and knowledge. Proceedings of IRIS. 2001;24:11–4.

Estabrooks CA, Rutakumwa W, O’Leary KA, Profetto-McGrath J, Milner M, Levers MJ, et al. Sources of practice knowledge among nurses. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(4):460–76.

Weick KE, Sutcliffe KM, Obstfeld D. Organizing and the process of sensemaking. Organ Sci. 2005;16(4):409–21.

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108.

Pluye P, Hong QN. Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;35:29–45.

Estabrooks CA, Chong H, Brigidear K, Profetto-McGrath J. Profiling Canadian nurses’ preferred knowledge sources for clinical practice. Can J Nurs Res. 2005;37(2):118–40.

Cook DA, Levinson AJ, Garside S, Dupras DM, Erwin PJ, Montori VM. Internet-based learning in the health professions: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1181–96.

Haug JD. Physicians’ preferences for information sources: a meta-analytic study. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1997;85(3):223–32.

Househ MS, Kushniruk A, Carleton B, Cloutier-Fisher D. A literature review on distance knowledge exchange in healthcare groups: what can we learn from the ICT literature? J Med Syst. 2011;35(4):639–46.

Pentland D, Forsyth K, Maciver D, Walsh M, Murray R, Irvine L, et al. Key characteristics of knowledge transfer and exchange in healthcare: integrative literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(7):1408–25.

Pluye P, Robert E, Cargo M, Bartlett G, O’Cathain A, Griffiths F, et al. Proposal: a mixed methods appraisal tool for systematic mixed studies reviews. 2011. Available from: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com Archived at WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/5tTRTc9yJ. Accessed 12 Mar 2017.

Kwasnik BH. The role of classification in knowledge represantation and discovery. Library trends. 1999;48(1):22–47.

Ellis D, Vasconcelos A, editors. Ranganathan and the Net: using facet analysis to search and organise the World Wide Web. Aslib proceedings. MCB UP Ltd. 1999;51(1):3-10.

Li Y, Belkin NJ. A faceted approach to conceptualizing tasks in information seeking. Inf Process Manag. 2008;44(6):1822–37.

Broughton V. Faceted classification as a basis for knowledge organization in a digital environment; the Bliss Bibliographic Classification as a model for vocabulary management and the creation of multidimensional knowledge structures. New Rev Hypermedia M. 2001;7(1):67–102.

Broughton V, editor. The need for a faceted classification as the basis of all methods of information retrieval. Aslib proceedings. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. 2006;58(1/2):49-72.

Al-Ghabeesh SH, Abu-Moghli F, Salsali M, Saleh M. Exploring sources of knowledge utilized in practice among Jordanian registered nurses. J Eval Clin Pract. 2013;19(5):889–94.

Ammary-Risch N, Kwon HT, Scarbrough W, Higginbotham E, Heath-Watson S. Minority primary care physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices on eye health and preferred sources of information. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101(12):1247–53.

Andrews JE, Pearce KA, Ireson C, Love MM. Information-seeking behaviors of practitioners in a primary care practice-based research network (PBRN). J Med Libr Assoc. 2005;93(2):206–12.

Ankem K. Influence of information sources on the adoption of uterine fibroid embolization by interventional radiologists. J Med Libr Assoc. 2003;91(4):450–9.

Apalayine GB, Ehikhamenor FA. The information needs and sources of primary health care workers in the Upper East Region of Ghana. J Inf Sci. 1996;22(5):367–73.

Arroll B, Pandit S, Kerins D, Tracey J, Kerse N. Use of information sources among New Zealand family physicians with high access to computers. J Fam Pract. 2002;51(8).

Asefzadeh S, Rafati M. How do physicians and dentists update their information after graduation. The 4th International Scientific Conference: Elearning And Software For Eduction. Buhcarest: Carol I National Defense University; 2008. https://adlunap.ro/else../papers/035.-515.1.Asfzadeh%20S.%20-%20How%20to%20Update%20Physicians.pdf.

Barley M, Pope C, Chilvers R, Sipos A, Harrison G. Guidelines or mindlines? A qualitative study exploring what knowledge informs psychiatrists decisions about antipsychotic prescribing. J Ment Health. 2008;17(1):9–17.

Beaulieu M-D, Proulx M, Jobin G, Kugler M, Gossard F, Denis J-L, et al. When is knowledge ripe for primary care? An exploratory study on the meaning of evidence. Eval Health Prof. 2008;31(1):22–42.

Bennett NL, Casebeer LL, Kristofco R, Collins BC. Family physicians’ information seeking behaviors: a survey comparison with other specialties. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2005;5:9.

Bennett NL, Casebeer LL, Zheng S, Kristofco R. Information-seeking behaviors and reflective practice. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(2):120–7.

Bernard E, Arnould M, Saint-Lary O, Duhot D, Hebbrecht G. Internet use for information seeking in clinical practice: a cross-sectional survey among French general practitioners. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81(7):493–9.

Bonner A, Lloyd A. What information counts at the moment of practice? Information practices of renal nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(6):1213–21.

Botello-Harbaum MT, Demko CA, Curro FA, Rindal DB, Collie D, Gilbert GH, et al. Information-seeking behaviors of dental practitioners in three practice-based research networks. J Dent Educ. 2013;77(2):152–60.

Bryant SL. The information needs and information seeking behaviour of family doctors. Health Info Libr J. 2004;21(2):84–93.

Butzlaff M, Koneczny N, Floer B, Vollmar HC, Lange S, Kunstmann W, et al. Family physicians, the internet and new knowledge. Utilization and judgment of efficiency of continuing education media by general physicians and internists in family practice. [German] Hausarzte, Internet und neues Wissen. Nutzung und Effizienzeinschatzung von Fortbildungsmedien durch Allgemeinarzte und hausarztlich tatige Internisten. Medizinische Klinik (Munich, Germany: 1983). 2002;97(7):383–8.

Callen JL, Buyankhishig B, McIntosh JH. Clinical information sources used by hospital doctors in Mongolia. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77(4):249–55.

Chang J, Kim HY, Cho BH, Lee IB, Son HH. Information resources and material selection in bonded restorations among Korean dentists. J Adhes Dent. 2009;11(6):439–46.

Chew-Graham CA, Cahill G, Dowrick C, Wearden A, Peters S. Using multiple sources of knowledge to reach clinical understanding of chronic fatigue syndrome. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):340–8.

Clarke CL, Wilcockson J. Seeing need and developing care: exploring knowledge for and from practice. Int J Nurs Stud. 2002;39(4):397–406.

Cogdill KW. Information needs and information seeking in primary care: a study of nurse practitioners. J Med Libr Assoc. 2003;91(2):203–15.

Curley SP, Connelly DP, Rich EC. Physicians use of medical knowledge resources - preliminary theoretical framework and findings. Med Decis Making. 1990;10(4):231–41.

Dee C, Blazek R. Information needs of the rural physician: a descriptive study. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1993;81(3):259–64.

Elliott TE, Elliott BA. Physician acquisition of cancer pain management knowledge. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1991;6(4):224–9.

Estabrooks CA. Will evidence-based nursing practice make practice perfect? Can J Nurs Res. 1998;30(1):15–36.

Fairhurst K, Huby G. From trial data to practical knowledge: qualitative study of how general practitioners have accessed and used evidence about statin drugs in their management of hypercholesterolaemia. BMJ. 1998;317(7166):1130–4.

Gagliardi AR, Wright FC, Davis D, McLeod RS, Urbach DR. Challenges in multidisciplinary cancer care among general surgeons in Canada. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2008;8:59.

Gavino AI, Ho BLC, Wee PAA, Marcelo AB, Fontelo P. Information-seeking trends of medical professionals and students from middle-income countries: a focus on the Philippines. Health Info Libr J. 2013;30(4):303–17.

Gerrish K, Ashworth P, Lacey A, Bailey J. Developing evidence-based practice: experiences of senior and junior clinical nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):62–73.

Gonzalez-Gonzalez AI, Dawes M, Sanchez-Mateos J, Riesgo-Fuertes R, Escortell-Mayor E, Sanz-Cuesta T, et al. Information needs and information-seeking behavior of primary care physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(4):345–52.

Gravois SL, Bowen DM, Fisher W, Patrick SC. Dental hygienists’ information seeking and computer application behavior.[Erratum appears in J Dent Educ 1996 Mar;60(3):312]. Journal of Dental Education. 1995;59(11):1027-33

Jackson R, Baird W, Davis-Reynolds L, Smith C, Blackburn S, Allsebrook J. The information requirements and information-seeking behaviours of health and social care professionals providing care to children with health care needs: a pilot study. Health Info Libr J. 2007;24(2):95–102.

James I, Andershed B, Gustavsson B, Ternestedt BM. Knowledge constructions in nursing practice: understanding and integrating different forms of knowledge. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(11):1500–18.

Kosteniuk JG, D'Arcy C, Stewart N, Smith B. Central and peripheral information source use among rural and remote registered nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2006;55(1):100–14.

Kosteniuk JG, Morgan DG, D'Arcy CK. Use and perceptions of information among family physicians: sources considered accessible, relevant, and reliable. J Med Libr Assoc. 2013;101(1):32–7.

Martinez-Silveira MS, Oddone N. Information-seeking behavior of medical residents in clinical practice in Bahia, Brazil. J Med Libr Assoc. 2008;96(4):381–4.

McCord G, Smucker WD, Selius BA, Hannan S, Davidson E, Schrop SL, et al. Answering questions at the point of care: do residents practice EBM or manage information sources? Acad Med. 2007;82(3):298–303.

McGettigan P, Golden J, Fryer J, Chan R, Feely J. Prescribers prefer people: the sources of information used by doctors for prescribing suggest that the medium is more important than the message. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;51(2):184–9.

McKnight M. The information seeking of on-duty critical care nurses: evidence from participant observation and in-context interviews RMP. J Med Libr Assoc. 2006;94(2):145–51.

Mills J, Field J, Cant R. The place of knowledge and evidence in the context of Australian general practice nursing. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2009;6(4):219–28.

Nail-Chiwetalu B, Ratner NB. An assessment of the information-seeking abilities and needs of practicing speech-language pathologists. J Med Libr Assoc. 2007;95(2):182–8.

Nichols A, Badger B. An investigation of the division between espoused and actual practice in infection control and of the knowledge sources that may underpin this division. Br J Infect Control. 2008;9(4):11–5.

Nieri M, Mauro S. Continuing professional development of dental practitioners in Prato, Italy. J Dent Educ. 2008;72(5):616–25.

Norbert GL, Lwoga ET. Information seeking behaviour of physicians in Tanzania. Inf Dev. 2013;29(2):172–82.

Northup DE, Moore-West M, Skipper B, Teaf SR. Characteristics of clinical information-searching: investigation using critical incident technique. Acad Med. 1983;58(11):873–81.

Nylenna M, Aasland OG. Primary care physicians and then information-seeking behaviour. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2000;18(1):9–13.

O'Leary DF, Ni MS. Information-seeking behaviour of nurses: where is information sought and what processes are followed? J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(2):379–90.

Oliveri RS, Gluud C, Wille-Jørgensen PA. Hospital doctors’ self-rated skills in and use of evidence-based medicine—a questionnaire survey. J Eval Clin Pract. 2004;10(2):219–26.

Ozsoy SA, Ardahan M. Research on knowledge sources used in nursing practices. Nurse Educ Today. 2008;28(5):602–9.

Papp KK, Penrod CE, Strohl KP. Knowledge and attitudes of primary care physicians toward sleep and sleep disorders. Sleep Breath. 2002;6(3):103–9.

Peay MY, Peay ER. Differences among practitioners in patterns of preference for information-sources in the adoption of new drugs. Soc Sci Med. 1984;18(12):1019–25.

Pelzer NL, Leysen JM. Use of information resources by veterinary practitioners. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1991;79(1):10.

Perzeski DM. Information-seeking behaviors of podiatric physicians. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2012;102(6):451–62.

Ramos K, Linscheld R, Schafer S. Real-time information-seeking behavior of residency physicians. Fam Med-Kansas City. 2003;35(4):257–60.

Rappolt S, Tassone M. How rehabilitation therapists gather, evaluate, and implement new knowledge. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2002;22(3):170–80.

Robertson J, Moxey AJ, Newby DA, Gillies MB, Williamson M, Pearson S-A. Electronic information and clinical decision support for prescribing: state of play in Australian general practice. Fam Pract. 2011;28(1):93–101.

Secco ML, Woodgate RL, Hodgson A, Kowalski S, Plouffe J, Rothney PR, et al. A survey study of pediatric nurses’ use of information sources. Comput Inform Nurs. 2006;24(2):105–12.

Selvi F, Ozerkan AG. Information-seeking patterns of dentists in Istanbul, Turkey. J Dent Educ. 2002;66(8):977–80.

Shelstad KR, Clevenger FW. Information retrieval patterns and needs among practicing general surgeons: a statewide experience. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1996;84(4):490–7.

Sibbald SL, Wathen CN, Kothari A, Day AM. Knowledge flow and exchange in interdisciplinary primary health care teams (PHCTs): an exploratory study. J Med Libr Assoc. 2013;101(2):128–37.

Stetler CB, DiMaggio G. Research utilization among clinical nurse specialists. Clin Nurse Spec. 1991;5(3):151–5.

Straub-Morarend CL, Marshall TA, Holmes DC, Finkelstein MW. Informational resources utilized in clinical decision making: common practices in dentistry. J Dent Educ. 2011;75(4):441–52.

Strother EA, Lancaster DM, Gardiner J. Information needs of practicing dentists. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1986;74(3):227–30.

Tabatabaei-Malazy O, Nedjat S, Majdzadeh R. Which information resources are used by general practitioners for updating knowledge regarding diabetes? Arch Iran Med. 2012;15(4):223–7.

Thompson C, McCaughan D, Cullum N, Sheldon TA, Mulhall A, Thompson DR. Research information in nurses’ clinical decision-making: what is useful? J Adv Nurs. 2001;36(3):376–88.

Timpka T, Ekstrom M, Bjurulf P. Information needs and information seeking behaviour in primary health care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1989;7(2):105–9.

Urquhart C, Crane S. Nurses’ information-seeking skills and perceptions of information sources: assessment using vignettes. J Inf Sci. 1994;20(4):237–46.

Vollmar HC, Rieger MA, Butzlaff ME, Ostermann T. General Practitioners’ preferences and use of educational media: a German perspective. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:31.

Wardh I, Axelsson S, Tegelberg A. Which evidence has an impact on dentists’ willingness to change their behavior? J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2009;9(4):197–205.

Warren-Findlow J, Price AE, Hochhalter AK, Laditka JN. Primary care providers’ sources and preferences for cognitive health information in the United States. Health Promot Int. 2010;25(4):464–73.

Weng YH, Kuo KN, Yang CY, Lo HL, Shih YH, Chiu YW. Information-searching behaviors of main and allied health professionals: a nationwide survey in Taiwan. J Eval Clin Pract. 2013;19(5):902–8.

Yadav BL, Fealy GM. Irish psychiatric nurses’ self-reported sources of knowledge for practice. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2012;19(1):40–6.

Yousefi-Nooraie R, Shakiba B, Mortaz-Hedjri S, Soroush AR. Sources of knowledge in clinical practice in postgraduate medical students and faculty members: a conceptual map. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13(4):564–8.

Bringsvor HB, Bentsen SB, Berland A. Sources of knowledge used by intensive care nurses in Norway: an exploratory study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2014;30(3):159–66.

Buckley T, Stasa H, Cashin A, Stuart M, Dunn SV. Sources of information used to support quality use of medicines: findings from a national survey of nurse practitioners in Australia. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2015;27(2):87–94.

Neher M, Stahl C, Ellstrom PE, Nilsen P. Knowledge sources for evidence-based practice in rheumatology nursing. Clin Nurs Res. 2015;24(6):661–79.

Sarbaz M, Kimiafar K, Sheikhtaheri A, Taherzadeh Z, Eslami S. Nurses’ information seeking behavior for clinical practice: a case study in a developing country. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2016;225:23–7.

Wenger E. Communities of practice: learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998.

Oborn E, Barrett M, Racko G. Knowledge translation in healthcare: incorporating theories of learning and knowledge from the management literature. J Health Organ Manag. 2013;27(4):412–31.

Kemmis S. Knowing practice: searching for saliences. Pedagogy, Culture Society. 2005;13(3):391–426.

Higgs J, Titchen A. Practice knowledge and expertise in the health professions. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2001.

Eraut M. Non-formal learning and tacit knowledge in professional work. Br J Educ Psychol. 2000;70(Pt 1):113–36.

Hurst D. Knowledge encounter simulation 2015 [cited 2016. Available from: https://goo.gl/forms/0CBpSP3KR1NaU5th2 Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6kLdtieGH]. Accessed 12 Mar 2017.

Bradburn NM, Rips LJ, Shevell SK. Answering autobiographical questions: the impact of memory and inference on surveys. Science. 1987;236(4798):157–61.

Mays N, Pope C. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ [Br Med J]. 2000;320(7226):50.

Stone A, Shiffman S, Atienza A. Science of real-time data capture: self-reports in health research. Cary: Oxford University Press, USA; 2007.

Freedman MJ, Lester KM, McNamara C, Milby JB, Schumacher JE. Cell phones for ecological momentary assessment with cocaine-addicted homeless patients in treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;30(2):105–11.

Gaggioli A, Pioggia G, Tartarisco G, Baldus G, Corda D, Cipresso P, et al. A mobile data collection platform for mental health research. Pers Ubiquit Comput. 2013;17(2):241–51.

Jamison RN, Raymond SA, Levine JG, Slawsby EA, Nedeljkovic SS, Katz NP. Electronic diaries for monitoring chronic pain: 1-year validation study. Pain. 2001;91(3):277–85.

Morren M, van Dulmen S, Ouwerkerk J, Bensing J. Compliance with momentary pain measurement using electronic diaries: a systematic review. Eur J Pain. 2009;13(4):354–65.

Kwasnik BH. The role of classification structures in reflecting and building theory. Advances in Classification Research Online. 1992;3(1):63–82.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the general dental practitioners who kindly tested the classification and who fed back on its usability, which will inform future iterations of the classification. We are grateful to our reviewers and to the associate editor, for their constructive comments on the first submission of this article.

Funding

This review was self-funded.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the Figshare repository https://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.3494201.

Authors’ contributions

DH conceived of the study, designed it, completed all data extraction and analysis and wrote the manuscript. SM assisted in the conception and design, data extraction and critical reading of drafts. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Competing interests

This review has been undertaken as part of a DPhil programme at the University of Oxford. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Search strategy. (PDF 448 kb)

Additional file 2:

Included studies. (PDF 598 kb)

Additional file 3:

Information and experiences extracted from included studies. (PDF 329 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hurst, D., Mickan, S. Describing knowledge encounters in healthcare: a mixed studies systematic review and development of a classification. Implementation Sci 12, 35 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0564-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0564-1