Abstract

Background

The study examined the effects of Happy Mother—Healthy Baby (HMHB), a cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) intervention on breastfeeding outcomes for Pakistani women with prenatal anxiety.

Methods

Breastfeeding practices were evaluated in a randomized controlled trial between 2019 and 2022 in a public hospital in Pakistan. The intervention group was randomized to receive six HMHB sessions targeted towards prenatal anxiety (with breastfeeding discussed in the final session), while both groups also received enhanced usual care. Breastfeeding was defined in four categories: early breastfeeding, exclusive early breastfeeding, recent breastfeeding, and exclusive recent breastfeeding. Early breastfeeding referred to the first 24 h after birth and recent breastfeeding referred to the last 24 h before an assessment at six-weeks postpartum. Potential confounders included were mother’s age, baseline depression and anxiety levels, stress, social support, if the first pregnancy (or not) and history of stillbirth or miscarriage as well as child’s gestational age, gender. Both intent-to-treat and per-protocol analyses were examined. Stratified analyses were also used to compare intervention efficacy for those with mild vs severe anxiety.

Results

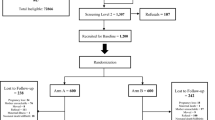

Out of the 1307 eligible women invited to participate, 107 declined to participate and 480 were lost to follow-up, resulting in 720 women who completed the postpartum assessment. Both intervention and control arms were similar on demographic characteristics (e.g. sex, age, income, family structure). In the primary intent-to-treat analysis, there was a marginal impact of the intervention on early breastfeeding (OR 1.38, 95% CI: 0.99–1.92; 75.4% (N = 273) vs. 69.0% (N = 247)) and a non-significant association with other breastfeeding outcomes (OR1.42, 95% CI: 0.89–2.27; (47) 12.9% vs. (34) 9.5%, exclusive early breastfeeding; OR 1.48, 95% CI: 0.94–2.35; 90% (N = 327) vs. 86% (N = 309), recent breastfeeding; OR1.01, 95% CI: 0.76–1.35; 49% (N = 178) vs 49% (N = 175) exclusive recent breastfeeding). Among those who completed the intervention’s six core sessions, the intervention increased the odds of early breastfeeding (OR1.69, 95% CI:1.12–2.54; 79% (N = 154) vs. 69% (N = 247)) and recent breastfeeding (OR 2.05, 95% CI:1.10–3.81; 93% (N = 181) vs. 86% (N = 309)). For women with mild anxiety at enrolment, the intervention increased the odds of recent breastfeeding (OR 2.41, 95% CI:1.17–5.00; 92% (N = 137) vs. 83% (N = 123).

Conclusions

The study highlights the potential of CBT-based interventions like HMHB to enhance breastfeeding among women with mild perinatal anxiety, contingent upon full participation in the intervention.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03880032.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Lactation has developed through evolutionary processes to create an optimal system for delivering essential nutrients in sufficient quantities from mothers to their offspring [1]. Breastfeeding has considerable impacts on children's cognition, behavior, physical growth and development, as well as effects on the mothers’ physical and psychological wellbeing [2, 3, 4]. The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests that breastfeeding should continue exclusively, meaning that the infant is only fed with breastmilk, for at least six months [5]. Exclusive breastfeeding can lead to a 10% reduction in the disease burden among children below the age of five [6]. Pakistan, with more than five million children born each year, has one of the highest numbers of births in the world [7]. However, exclusive breastfeeding practices in Pakistan have fallen short of recommended targets. According to the Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey, only 48% of children less than six months of age are exclusively breastfed, while 53% of children receive any breastmilk until the age of two years old [8]. This means only approximately half of children under 6 months are exclusively breastfed, indicating a need for improved breastfeeding practices in Pakistan.

Perinatal anxiety can negatively affect maternal functioning, resulting in emotional distress, and potential disruptions in the formation of the mother-infant bond as well as less likelihood of breastfeeding [9, 10, 11]. Low breastfeeding self-efficacy is a major contributor to discontinuation of exclusive breastfeeding [12]. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has been recommended to promote breastfeeding in pregnant and new mothers in lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs) by promoting counselling, social support, education and women’s empowerment [13, 14].

Given that women with anxiety are at a higher risk of discontinuing exclusive and continued breastfeeding practices [9, 10, 15], we sought to evaluate a CBT-based intervention, called Happy Mother, Healthy Baby (HMHB), for women with prenatal anxiety in Pakistan that included a session involving the discussion of and encouraged support for breastfeeding. In follow-up assessment at six weeks after birth, HMHB was effective in reducing the odds of depression by 81% (OR 0.19, 95% CI: 0.13–0.28), with 11.6% (N = 44) of intervention participants with postpartum depression versus 40.5% (N = 152) of control participants with postpartum depression. HMHB also reduced the odds of moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety by 74% (OR 0.26, 95% CI: 0.17–0.40), with 8.7% (N = 33) of intervention participants versus 26.7% (N = 100) control participants having moderate-to-severe postpartum anxiety symptoms [16]. Given the inclusion of guidance on breastfeeding in the intervention, we sought to evaluate the effect of an anxiety-focused maternal mental health intervention using CBT on breastfeeding outcomes among women with symptoms of at least mild anxiety in Pakistan.

Methods

Study setting and participant recruitment

Data for this study were obtained from a single-blinded randomized controlled trial to study the effectiveness of the Healthy Mother—Happy Baby (HMHB) intervention to reduce anxiety among pregnant women (clinicaltrial.gov identifier: NCT03880032) [17]. The study recruited 1200 women from Holy Family Hospital (HFH), a public facility in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, between 16th April 2019 until 31 January 2022. HFH is located in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, is a large facility with around 900 beds, making it a major regional healthcare facility. Annually, around 5,000 births are delivered at HFH, evidence of its crucial role in maternal and neonatal care in the region where it serves a diverse population from urban, rural, and semi-urban areas. All participants were recruited by female research assistants in the outpatient Gynaecology and Obstetrics Department during their initial prenatal visit. Participants were followed up at six-weeks after birth.

Screening and inclusion criteria

The study employed three levels of inclusion/exclusion screening criteria during the enrolment process. In the first level, women had to be at ≤ 22 weeks' gestation, ≥ 18 years old, reside ≤ 20 km from HFH, and have a basic understanding of Urdu. Women who met these criteria and showed willingness to participate were asked to provide informed consent. At the second level of screening, potential participants were excluded if reporting life-threatening health conditions, such as active severe depression or suicidal ideation. Other exclusions included self-reported significant learning disabilities, a self-reported psychiatric disorder or ongoing psychiatric care, medical disorders or severe maternal morbidity requiring inpatient management, and ICU admission indicated by diagnosis (not solely for assessment purposes), past or current significant learning disabilities, past or current psychiatric disorders, medical disorders, or severe maternal morbidity. At the third level of screening, potential participants were assessed for the presence of at least mild anxiety using the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) screening tool. Those who scored ≥ 8 on the HADS anxiety sub-scale (indicating at least mild anxiety) were interviewed by trained assessors who conducted a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV Diagnoses (SCID) to rule out depression. Women who met the conditions for a major depressive episode (MDE) were not included. MDE was defined using a diagnostic semi-structured guide from the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (SCID), which is based on American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM). Assessment with this method is considered equivalent to a clinical diagnosis in line with the DSM criteria.

Randomization

Study participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention or control group using a pseudo random-number generator. The random sequence was assigned through permuted blocks of size 4, 8, 12, and 16. The assignment list was printed in order, with each assignment separately stored in opaque envelopes and numbered sequentially. Once an eligible individual consented to participate in the study, the research team proceeded by selecting the next available envelope to determine the individual's assignment into either the intervention or control arm. Throughout this process, the trial team, comprising the assessment team, principal investigators, and co-investigators, remained blinded to the allocation.

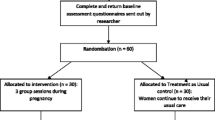

Study groups

Those randomized to the intervention group received the HMHB program, an intervention relying on principles of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) that aimed to reduce symptoms of anxiety during pregnancy [18]. It was adapted from WHO endorsed psychosocial intervention for perinatal depression called the Thinking Healthy Programme [19]. The intervention was delivered by non-specialist providers (with a two-year bachelor’s degree and a two-year master’s degree in psychology but no clinical experience). They were trained on the intervention and received regular weekly group supervision over the trial period. HMHB was designed to target risk factors for anxiety that women experienced during pregnancy that were identified in our preliminary research [18]. It also integrated stress management techniques, such as breathing exercises. To make the intervention more culturally appropriate, personalized illustrations were used in order to facilitate guided discovery, behavioural activation, stress reduction, and convey essential health messages [18]. The sessions were supplemented by take-home exercises.

HMHB consisted of six core weekly sessions and up to six optional booster sessions (delivered as needed). The first five weekly one-on-one sessions were intended for early to mid-pregnancy. The final sixth core session was given in the third trimester of pregnancy. This session was aimed to help manage anxiety during late pregnancy, prepare for baby’s arrival, and navigate the early post-natal period. It highlighted the importance of breastfeeding and providing colostrum as a pre-lacteal feed instead of culturally common practices involving feeding infants honey or herbal tonics. It also encouraged family support for mothers to breastfeed.

The control group received enhanced usual care at the Gynaecology and Obstetrics Department. Usual care recommended at the study hospital typically involves up to eight visits for evaluating health status, discussing any concerns, and performing routine exams consistent with the stage of pregnancy. The care of women participating in HMHB was enhanced by reminders for study visits, expedited care (shorter wait times), as well as reimbursement for transportation to visits and for as many ultrasounds as were medically indicated at HFH during pregnancy.

Breastfeeding indicators

In line with WHO definition of exclusive breastfeeding, women who confirmed providing only colostrum/breastmilk within the first 24 h and reported no use of formula, Ghutti (traditional pre-lacteal feed), herbal water, tea, or other animal milk were considered to have engaged in ‘early exclusive breastfeeding’. Breastfeeding women who reported both breastmilk and at least one other nutritional source fell into the ‘early breastfeeding’ category. We also assessed breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum by asking mothers if they were breastfeeding and if they had given breast milk or any other nutrition to their infants to determine whether it was exclusive or non-exclusive. These women were categorized as having engaged in ‘recent exclusive breastfeeding’ if no other nutrition source was provided or ‘recent breastfeeding’ if receiving both breastmilk and other nutrients. Our indicators for 'recent' breastfeeding practices, namely 'recent exclusive breastfeeding' and 'recent breastfeeding', pertain to exclusive and non-exclusive breastfeeding within 24 h before the six-week postpartum assessment. We chose the term 'recent' because it covers both exclusively breastfed infants and those receiving some breastmilk, unlike the WHO definition of 'predominant breastfeeding', which focuses solely on the infant's main source of nourishment.

Covariates

The hospital anxiety and depression scale

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is a well-known instrument that includes 14 items rated on a 4-point scale that has been validated in numerous languages and settings [20, 21]. The HADS focuses on non-physical symptoms to screen for anxiety and depression, but does not include all of the diagnostic criteria of depression specified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) [21]. For example, it does not include items on appetite, sleep and self-harm/suicidal thoughts [21]. It comprises two distinct subscales to assess anxiety and depression, each containing 7 items with scores ranging from 0 to 21. Typical symptom cut-offs are 0–7 (normal), 8–10 (mild), 11–14 (moderate), and 15–21 (severe). A cut-off of ≥ 8 was defined as the threshold for being ‘at risk’ for anxiety or depression. The Urdu adaptation of this scale has been previously modified for use in Pakistan and has been administered successfully [22] including in pregnant women [23], showing satisfactory reliability, validity, and high concurrence with the English version for use of the symptom threshold of ≥ 8 [24] when assessing antenatal anxiety and depression in Pakistan [25].

Perceived stress scale (PSS-10)

The PSS-10 is a validated global measure of perceived stress that consists of 10 items scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 to 4 (maximum score 40) [26]; higher scores indicate more stress. It has been adapted for use in Pakistan [27]. A score of ≥ 20 corresponds to high stress.

Multi-dimensional scale of social support (MSPSS)

The Multi-dimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) is a 12-item measure of subjective availability of support (primarily emotional) which has been validated and successfully adapted to the Pakistani context [28]. Scores are on a 7-point scale (1 = very strongly disagree; 7 = very strongly agree), with higher scores indicating more support.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were performed to investigate postpartum symptoms of depression and anxiety in relation to breastfeeding. In women with completed measures of breastfeeding outcomes, we examined the differences at baseline between intervention and control arms to verify that randomization generated comparable arms. We used standard statistical comparisons, including Chi-square test for categorical factors and Student’s t-test for continuous factors, to determine the statistical significance of any differences between arms. All analyses followed the intent-to-treat (ITT) principle unless otherwise noted, comparing the four breastfeeding outcomes in the groups to which they were randomized.

We compared early breastfeeding, exclusive early breastfeeding, recent breastfeeding, and exclusive recent breastfeeding outcomes between arms, where ‘early’ was defined as first 24 h after childbirth and ‘recent’ was defined as within the last 24 h before the assessment that occurred approximately six weeks postpartum. Comparisons between arms following the principle of ITT were estimated with logistic regression. In addition to the intent-to-treat analysis among all participants, we also performed a stratified analysis to separately estimate the intervention effects for women who had mild anxiety levels (HADS anxiety score: 8–11) and the intervention effects for women who had moderate to severe anxiety levels (HADS anxiety score: 11–21) at enrolment.

We also conducted an analysis to examine breastfeeding outcomes in a subset of women randomized to the intervention arm who only included those that received all six intervention sessions (“intervention completers”). We adjusted for potential confounders including gestational age, depression and anxiety at enrolment, stress at enrolment measured with the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10), general social support and social support from family (both measured with the Multidimensional Scale of Social Support (MSPSS)), maternal age, child’s sex, whether first pregnancy or not and history of stillbirth or miscarriage. Selection of confounding factors for adjustment was based on prior knowledge of what was expected to influence intervention session receipt and by examining the baseline variables for those with six intervention sessions compared to those in the control arm. Given breastfeeding was a secondary outcome, this study was not specifically powered to detect differences related to breastfeeding outcomes. Rather, it was powered to detect a difference in the six-week postpartum mental health outcomes of participants between arms among 1,200 enrolled participants with a 30% expected dropout rate.

Finally, we evaluated a dose response relationship for the intervention considering the receipt of booster sessions. Using the Cochrane Armitage test for trend, we examined this relationship for the four types of breastfeeding considered, across three dose groups, 1) control (no intervention), 2) only core intervention sessions, and 3) core and booster sessions.

Ethics

Ethical approval for this research was received from the Institutional Review Boards of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Health (IRB No. 00009177; Approved April 2, 2019), the Human Development Research Foundation Ethics Committee (IRB/001/2017; Approval March 10, 2017), and Global Mental Health Data Safety and Monitoring Board appointed by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in the United States (No assigned approval number; Approved March 11, 2019). Prior to their involvement in this study, all participants provided written informed consent, indicating their willingness to take part in the research.

Results

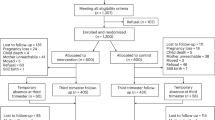

Out of over 91 thousand women screened, 1307 women met the inclusion criteria, including having moderate to high anxiety symptoms and not meeting the diagnostic criteria for clinical depression. Of these 1,307, 1,200 (92%) agreed to participate and were enrolled in the trial. Among the 1200 pregnant women who were enrolled 445 (37%) were lost to follow-up, mostly because they were unreachable or because they declined to participate later. The remaining 755 (63%) of enrolled pregnancies were followed until six weeks postpartum. Of those, 720 had complete measures on breastfeeding outcomes.

Descriptive statistics showed that breastfeeding was inversely related to symptoms of both depression and anxiety (Supplementary Table 1). The women were similar between arms at enrolment across all characteristics examined. This included maternal age (mean (SD) 25.1 (4.7) vs 25.3 (4.5) for intervention and control arms respectively; p = 0.519), whether it was the participant’s first pregnancy (98 (27%) vs 109 (30%); p = 0.359), having at least one other child at time of enrolment in pregnancy (204 (56%) vs 207 (58%); p = 0.104), and the participant having a history of stillbirth or miscarriage (160 (44%) vs 143 (40%), p = 0.280). Education, family structure, social support, and self-reported monthly income were also similar between arms. Participant baseline anxiety symptoms were mean (SD) 11.2 (2.0) vs 11.2 (1.9), depression 6.9 (2.9) vs 6.6 (2.6), in the intervention and control arms respectively. Perceived stress was also examined for differences and was similar across arms. A detailed description of participants with known breastfeeding outcomes by arm is shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1.

We estimated the intervention effects on the four measured breastfeeding outcomes, including early breastfeeding, exclusive early breastfeeding, recent breastfeeding, and exclusive recent breastfeeding, by comparing results of 362 women in the intervention arm and 358 women in the control arm. Overall, in the ITT analysis did not show statistical differences (p-value > 0.05) for any of the four breastfeeding outcomes between the intervention and control arms, although there was marginal evidence of an intervention effect on early breastfeeding (75.4% vs. 69.0% with p-value = 0.06). The detailed results for all four breastfeeding outcomes are shown in Table 2.

We also performed an exploratory analysis to compare intervention effects stratifying by anxiety symptoms levels at enrolment (Table 3). The estimated intervention impact among women with mild anxiety at enrolment was somewhat larger than among women with high baseline anxiety levels. We found that for women with mild anxiety, the intervention increased the odds of recent breastfeeding (92% vs. 83%, odds ratio (OR) 2.41, 95% CI: 1.17 to 5.00). A summary comparison by arm among women with mild anxiety and women with moderate to severe anxiety is included in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

In addition to our primary analysis, which was completed following the principle of intent-to-treat, we conducted additional analysis only involving 195 women in the intervention arm who received six intervention sessions (“intervention completers”), compared with all 358 women in control arm. As shown in Table 4, for participants receiving six intervention sessions, the intervention increased the odds of early breastfeeding (79% vs. 69%, OR 1.69, 95% CI: 1.12 to 2.54) and recent breastfeeding (93% vs. 86%, OR 2.05, 95% CI: 1.10 to 3.81). Women receiving six intervention sessions, although not randomized to receive the complete intervention, were similar to those in the control arm (Supplementary Table 4).

Finally, according to the test for trend to test differences between receiving no intervention, the six core sessions and six core and booster sessions, we found no significant association between any type of breastfeeding and dose of intervention (Supplemantary Table 6).

Discussion

The overall findings of the intent-to-treat analysis (including women who dropped out and did not receive all sessions) demonstrated no significant differences in any of the breastfeeding outcomes between the intervention and control arms. However, our results suggest that the HMHB intervention promoted early breastfeeding initiation and continuation for women who received the full six core sessions of the program. It is important to note that the intervention content overall did not primarily target breastfeeding and that content related to women’s perinatal well-being (focused on anxiety reduction) and the discussion of breastfeeding was presented only during the last visit of the program.

In other words, our finding of a significant impact only for those receiving the complete intervention dose may be because the relevant content was in the final session. Specifically, we observed an increase in both the odds of early breastfeeding initiation and in the odds of women continuing breastfeeding among women who attended the full intervention, compared to women in the control arm. Another study from Kenya showed that a series of home-based breastfeeding counselling sessions proved more effective in promoting exclusive breastfeeding compared to a single facility-based session, which was deemed insufficient [29]. Women’s health programs that provide personalized support during the perinatal period have demonstrated success in enhancing mental health and promoting breastfeeding outcomes in varied settings and contexts [30]. Given social support was also a component of several intervention sessions, it could also have potentially played a role in promoting breastfeeding behaviours.

A recent systematic review of 76 studies with 79 comparisons of breastfeeding interventions from 30 low- and middle-income countries showed almost every intervention increased exclusive breastfeeding rates [31]. In a study of pregnant women from a rural district in the northwest province of Pakistan, Sikander et al., found that compared with routine counselling, counselling using principles of CBT not only significantly prolonged the duration of exclusive breastfeeding but also doubled its rates at six months postpartum [13]. Studies conducted in other resource-constrained settings in Syria [32], India [33], and Bangladesh [34] and sub-Saharan Africa [35] have also shown effectiveness of home-based interventions aiming to promote breastfeeding behaviours among the mothers, even when delivered by non-specialist providers. Table 5 shows a comparison of different psychosocial interventions and their effects on breastfeeding in context of different LMICs.

In our study women with mild anxiety levels who received the intervention had over two-fold higher odds of reporting recent breastfeeding at the six-week postpartum time point compared to controls. This association was not significant among intervention participants who had moderate to high levels of anxiety, indicating heightened efficacy of HMHB in the low anxiety group. Numerous CBT interventions have produced significant results in improving mental health of the individuals with anxiety, yet they have not specified effects based on the severity of anxiety [9, 10, 15, 36, 37, 38]. To affect breastfeeding outcomes for women with severe mental health problems, a more intense intervention may be needed, whereas this CBT-based psychosocial intervention potentially fostered breastfeeding by stimulating the responsiveness of mothers with mild anxiety.

The HMHB intervention, while effective in promoting early breastfeeding initiation and continuation among those completing the program, primarily concentrated on addressing perinatal anxiety. It only briefly touched upon breastfeeding promotion in the final session. Therefore, given an association between perinatal common mental health disorders and breastfeeding, the positive effects we observed may also have been due to the ability of the program to reduce anxiety and depression. This is supported by the literature. For example in a study conducted in Turkey by Çiftçi and Arikan in 2012, an association was observed between the presence of postnatal maternal anxiety levels and a decline in the exclusivity and continuation of breastfeeding [39]. Research recommends actively monitoring and appropriately managing maternal anxiety during the postpartum period to foster optimal breastfeeding practices [39, 40, 41]. It has been suggested that use of intrapartum analgesia (fentanyl) during labor and antidepressants used during pregnancy (including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)) significantly reduce breastfeeding [40, 41], which highlights the need for comprehensive lactation support in maternal healthcare especially for women with mental health conditions. Another single-session intervention (coupled with monthly telephone support), targeted postpartum mothers with depression while providing information on mental health, the benefits of breastfeeding and tips for successful breastfeeding. The findings indicated significant improvements in exclusive breastfeeding and breastfeeding practices, which were correlated with a reduction in postpartum depression within three months [42].

The prevailing social norms regarding breastfeeding in Pakistani culture discourage breastfeeding by not providing adequate support to mothers, making them feel uncomfortable breastfeeding in public and at the workplace [43]. Our study suggests that a CBT intervention for promoting breastfeeding practices among anxious women holds promise in Pakistan and potentially in other similar LMIC settings. The results highlight the importance of the full dose of the intervention in supporting successful breastfeeding for anxious mothers in a setting that falls short of WHO breastfeeding targets. In light of these findings, further investigation through mediation analyses could offer valuable insights into the mechanisms explaining the association between the full dose of the intervention and breastfeeding.

Strengths and limitations

One notable strength of our study is that we used a randomized controlled trial design to evaluate the effects of an the intervention for women with at least mild prenatal anxiety symptoms, a high risk group for discontinued breastfeeding [37]. However, given this focus, our findings may not be generalizable to non-anxious women of reproductive age in Pakistan. Regarding recruitment, of the 1307 women who were eligible, 107 deeclined to participate resulting in a mismatch between the eligible population and those who participated. However, we lacked information on those who did not participate in order to evaluate whether volunteer bias was a problem in our study (i.e., if those who declined to participate differed from those who agreed to participate). The trial was not originally designed to evaluate breastfeeding as a primary outcome, which may have led to the study being underpowered to assess breastfeeding. Further, since our study was hospital-based, results may not be transferrable to women in rural areas or those who typically give birth at home. Another limitation pertains to our reliance on retrospective recall of breastfeeding that corresponded to the initial 24-h period following birth, which was asked at six weeks postpartum. Further, the use of only one timepoint to assess breastfeeding may have also resulted in our missing important variation and changes in breastfeeding behaviors over time. The omission of some relevant variables, such as delivery type (e.g. vaginal versus caesarean), mother-newborn separation, prior breastfeeding experience, intention to breastfeed, and medication usage during labor makes it difficult to attribute our findings solely to the intervention, underscoring the need for additional research. Finally, we had a high rate of loss to follow-up, the analysis of which showed differences between participants enrolled and who completed the study related to gestational age at birth, education level, and income [16]. This may be partially due to the fact our data collection overlapped with the COVID-19 pandemic, during which many women were afraid to use hospital facilities [44].

Conclusion

The study did not reveal any significant effect of the anxiety focused psychosocial intervention on breastfeeding outcomes in intent-to-treat analyses. However, findings of more robust effects in women with mild anxiety (compared to more severe cases) support the potential use of HMHB in promoting recent breastfeeding practices specifically among women who have mild symptoms of anxiety. A different kind or more intense intervention may be needed to promote breastfeeding among women with higher levels of anxiety. Moreover, several other factors contribute to the challenges of breastfeeding including family support, employment, and childcare, affecting the overall lower breastfeeding rates in Pakistan [43]. Future studies are needed to investigate the intersecting role of these factors in the promotion of breastfeeding, and to understand why we observed stronger effects for women with only mild anxiety in our study. More research is needed to establish if HMHB is effective for the general population of non-anxious women and how it could be tailored to be effective for the most anxious women.

Availability of data and materials

The data used in this study can be accessed at the US National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Data Archive: https://nda.nih.gov/.

Abbreviations

- CBT:

-

Cognitive behavioural therapy

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale

- HFH:

-

Holy Family Hospital

- HMHB:

-

Happy Mother - Healthy Baby

- ITT:

-

Intent-to-treat

- LMIC:

-

Lower- and middle-income countries

- MDE:

-

Major depressive episode

- MSPSS:

-

Multidimensional Scale of Social Support

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- SCID:

-

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM V Diagnoses

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Hinde K, German JB. Food in an evolutionary context: insights from mother’s milk. J Sci Food Agric. 2012;92(11):2219–23.

Heinig MJ, Dewey KG. Health effects of breast feeding for mothers: a critical review. Nutr Res Rev. 1997;10(1):35–56.

Krol KM, Grossmann T. Psychological effects of breastfeeding on children and mothers. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2018;61(8):977.

Raju TNK. Breastfeeding is a dynamic biological process—not simply a meal at the breast. Breastfeed Med. 2011;6(5):257–9.

World Health Organisation. Exclusive breastfeeding for six months best for babies everywhere. https://www.who.int/news/item/15-01-2011-exclusive-breastfeeding-for-six-months-best-for-babies-everywhere2011. Accessed 10 June 2024

Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, De Onis M, Ezzati M, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. The lancet. 2008;371(9608):243–60.

UNICEF. Millions of pregnant mothers and babies born during COVID-19 pandemic threatened by strained health systems and disruptions in services. https://www.unicef.org/rosa/press-releases/millions-pregnant-mothers-and-babies-born-during-covid-19-pandemic-threatened2021. Accessed 10 June 2024

PDHS. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017–18. Islamabad, Pakistan and Rockville, Maryland, USA: National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) [Pakistan] and ICF; 2018.

Hoff CE, Movva N, Rosen Vollmar AK, Pérez-Escamilla R. Impact of maternal anxiety on breastfeeding outcomes: a systematic review. Adv Nutr. 2019;10(5):816–26.

Adedinsewo DA, Fleming AS, Steiner M, Meaney MJ, Girard AW, team M. Maternal anxiety and breastfeeding: findings from the MAVAN (Maternal Adversity, Vulnerability and Neurodevelopment) Study. J Hum Lactat. 2014;30(1):102–9.

Ross LE, McLean LM, Psych C. Anxiety disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;6(9):1–14.

Rahmatnejad L, Bastani F. Factors associated with discotinuation of exclusive breast feeding by first time mothers. Iran J Nurs. 2011;24(71):42–53.

Sikander S, Maselko J, Zafar S, Haq Z, Ahmad I, Ahmad M, et al. Cognitive-behavioral counseling for exclusive breastfeeding in rural pediatrics: a cluster RCT. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):e424–31.

Hofmann SG, Asmundson GJ, Beck AT. The science of cognitive therapy. Behav Ther. 2013;44(2):199–212.

Fairlie TG, Gillman MW, Rich-Edwards J. High pregnancy-related anxiety and prenatal depressive symptoms as predictors of intention to breastfeed and breastfeeding initiation. J Womens Health. 2009;18(7):945–53.

Surkan PJ, Malik A, Perin J, Atif N, Rowther A, Zaidi A, et al. Anxiety-focused cognitive behavioral therapy delivered by non-specialists to prevent postnatal depression: a randomized, phase 3 trial. Nat Med. 2024;30(3):675–82.

Surkan PJ, Hamdani SU, Huma Z-E, Nazir H, Atif N, Rowther AA, et al. Cognitive–behavioral therapy-based intervention to treat symptoms of anxiety in pregnancy in a prenatal clinic using non-specialist providers in Pakistan: design of a randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2020;10(4): e037590.

Atif N, Nazir H, Zafar S, Chaudhri R, Atiq M, Mullany LC, et al. Development of a psychological intervention to address anxiety during pregnancy in a low-income country. Front Psych. 2020;10:927.

Rahman A, Malik A, Sikander S, Roberts C, Creed F. Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9642):902–9.

Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale: an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77.

Stern AF. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Occup Med. 2014;64(5):393–4.

Dodani S, Zuberi RW. Center-based prevalence of anxiety and depression in women of the northern areas of Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2000;50(5):138–40.

Lodhi FS, Elsous AM, Irum S, Khan AA, Rabbani U. Psychometric properties of the Urdu version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) among pregnant women in Abbottabad, Pakistan. Gen Psychiatry. 2020;33(5):e100276.

Mumford DB, Tareen IA, Bajwa MA, Bhatti MR, Karim R. The translation and evaluation of an Urdu version of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991;83(2):81–5.

Waqas A, Aedma KK, Tariq M, Meraj H, Naveed S. Validity and reliability of the Urdu version of the hospital anxiety & depression scale for assessing antenatal anxiety and depression in Pakistan. Asian J Psychiatr. 2019;45:20–5.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–96.

Shamsi U, Hatcher J, Shamsi A, Zuberi N, Qadri Z, Saleem S. A multicentre matched case control study of risk factors for preeclampsia in healthy women in Pakistan. BMC Womens Health. 2010;10:14.

Rahman A, Hamdani SU, Awan NR, Bryant RA, Dawson KS, Khan MF, et al. Effect of a multicomponent behavioral intervention in adults impaired by psychological distress in a conflict-affected area of Pakistan: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(24):2609–17.

Ochola SA, Labadarios D, Nduati RW. Impact of counselling on exclusive breast-feeding practices in a poor urban setting in Kenya: a randomized controlled trial. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(10):1732–40.

Pezley L, Cares K, Duffecy J, Koenig MD, Maki P, Odoms-Young A, et al. Efficacy of behavioral interventions to improve maternal mental health and breastfeeding outcomes: a systematic review. Int Breastfeed J. 2022;17(1):67.

Olufunlayo TF, Roberts AA, MacArthur C, Thomas N, Odeyemi KA, Price M, et al. Improving exclusive breastfeeding in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15(3):e12788.

Bashour HN, Kharouf MH, AbdulSalam AA, El Asmar K, Tabbaa MA, Cheikha SA. Effect of postnatal home visits on maternal/infant outcomes in Syria: a randomized controlled trial. Public Health Nurs. 2008;25(2):115–25.

Bhandari N, Bahl R, Mazumdar S, Martines J, Black R, Bhan M. Infant feeding study group: effect of community-based promotion of exclusive breastfeeding on diarrhoeal illness and growth: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9367):1418–23.

Haider R, Ashworth A, Kabir I, Huttly SR. Effect of community-based peer counsellors on exclusive breastfeeding practices in Dhaka, Bangladesh: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;356(9242):1643–7.

Tylleskär T, Jackson D, Meda N, Engebretsen IMS, Chopra M, Diallo AH, et al. Exclusive breastfeeding promotion by peer counsellors in sub-Saharan Africa (PROMISE-EBF): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9789):420–7.

Richards D, Timulak L, Doherty G, Sharry J, McLoughlin O, Rashleigh C, et al. Low-intensity internet-delivered treatment for generalized anxiety symptoms in routine care: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15(145):1–11.

Wallwiener S, Müller M, Doster A, Plewniok K, Wallwiener CW, Fluhr H, et al. Predictors of impaired breastfeeding initiation and maintenance in a diverse sample: what is important? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;294:455–66.

Atif N, Rauf N, Nazir H, Maryam H, Mumtaz S, Zulfiqar S, et al. Non-specialist-delivered psychosocial intervention for prenatal anxiety in a tertiary care setting in Pakistan: a qualitative process evaluation. BMJ Open. 2023;13(2):e069988.

Çiftçi EK, Arikan D. The effect of training administered to working mothers on maternal anxiety levels and breastfeeding habits. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(15–16):2170–8.

Jordan S, Emery S, Bradshaw C, Watkins A, Friswell W. The impact of intrapartum analgesia on infant feeding. BJOG Int J Obstetr Gynaecol. 2005;112(7):927–34.

Jordan S, Davies GI, Thayer DS, Tucker D, Humphreys I. Antidepressant prescriptions, discontinuation, depression and perinatal outcomes, including breastfeeding: a population cohort analysis. Plos One. 2019;14(11):e0225133.

Franco-Antonio C, Santano-Mogena E, Chimento-Díaz S, Sánchez-García P, Cordovilla-Guardia S. A randomised controlled trial evaluating the effect of a brief motivational intervention to promote breastfeeding in postpartum depression. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):373.

Asim S, Mustafa DG. Breast feeding culture in Pakistan-a critical study. Sch Int J Obstet Gynec. 2022;5(10):414–44.

Rauf N, Zulfiqar S, Mumtaz S, Maryam H, Shoukat R, Malik A, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pregnant women with perinatal anxiety symptoms in Pakistan: a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8237.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the women participants and obstetric staff in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Rawalpindi Medical University. We are also thankful to Prof Muhammad Umar, Prof Rizwana Chaudhri and Prof Asad Tamizuddin Nizami of Rawalpindi Medical University for their support, both administrative and clinical, during our research from inception to completion. This study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health at the US National Institutes of Health (Grant # RO1 MH111859). The NIMH had no role in the conduct of this research.

Funding

Funding was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant number NIMH RO1 MH111859). The funding source had no role in the study design, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.N. drafted the introduction, some of the methods, and the discussion of the current manuscript. A.M. supervised the implementation of the study including data collection and all field activities, reviewed the manuscript and contributed to the interpretation of the results. H.X. performed the statistical analyses and drafted some of the methods and the results. J.P. supervised the statistical analysis and provided guidance and edits in the drafting of the statistical methods and results, reviewed the manuscript, and contributed to the interpretation of the results. N.A. led the development of the HMHB intervention, supervised its delivery, reviewed the manuscript and contributed to the interpretation of the results. A.Z. managed the data, cleaned and curated the data and constructed the flow chart. A.R. assisted in overall supervision of the field team, reviewed and edited the manuscript. P.J.S. contributed to the writing, the interpretation of results, and was the study’s principal investigator. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this research was received from the Institutional Review Boards of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Health (IRB No. 00009177; Approved April 2, 2019), the Human Development Research Foundation Ethics Committee (IRB/001/2017; Approval March 10, 2017), and Global Mental Health Data Safety and Monitoring Board appointed by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in the United States (No assigned approval number; Approved March 11, 2019). Prior to their involvement in this study, all participants provided written informed consent, indicating their willingness to take part in the research.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Nisar, A., Xiang, H., Perin, J. et al. Impact of an intervention for perinatal anxiety on breastfeeding: findings from the Happy Mother—Healthy Baby randomized controlled trial in Pakistan. Int Breastfeed J 19, 53 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-024-00655-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-024-00655-8