Abstract

Background

Despite extensive benefits and high intentions, few mothers breastfeed exclusively for the recommended duration. Maternal mental health is an important underlying factor associated with barriers and reduced rates of breastfeeding intent, initiation, and continuation. Given evidence of a bidirectional association between maternal mental health and breastfeeding, it is important to consider both factors when examining the efficacy of interventions to improve these outcomes. The purpose of this manuscript is to review the literature on the efficacy of behavioral interventions focused on both maternal mental health and breastfeeding outcomes, examining the intersection of the two.

Methods

This systematic review was completed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines. Studies were selected if they were available in English, used primary experimental design, and used a behavioral intervention type to examine maternal mental health and breastfeeding outcomes. Articles were identified from PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, and PsycINFO from database inception to 3 March 2022. Study quality was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. Results were synthesized by intervention success for 1. Mental health and breastfeeding, 2. Breastfeeding only, 3. Mental health only, and 4. No intervention effect. PROSPERO CRD42021224228.

Results

Thirty interventions reported in 33 articles were identified, representing 15 countries. Twelve studies reported statistically significant positive effect of the intervention on both maternal mental health and breastfeeding; most showing a decrease in self-report depressive and/or anxiety symptoms in parallel to an increase in breastfeeding duration and/or exclusivity. Common characteristics of successful interventions were a) occurring across pregnancy and postpartum, b) delivered by hospital staff or multidisciplinary teams, c) offered individually, and d) designed to focus on breastfeeding and maternal mental health or on breastfeeding only. Our results are not representative of all countries, persons, experiences, circumstances, or physiological characteristics.

Conclusions

Interventions that extend the perinatal period and offer individualized support from both professionals and peers who collaborate through a continuum of settings (e.g., health system, home, and community) are most successful in improving both mental health and breastfeeding outcomes. The benefits of improving these outcomes warrant continued development and implementation of such interventions.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42021224228.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Despite the many benefits of breastfeeding, few mothers breastfeed for the recommended duration. All major health and professional organizations, including the World Health Organization, American Academy of Pediatrics, and the United States (U.S.) Departments of Agriculture and Health and Human Services (Dietary Guidelines for Americans) [1,2,3] recommend exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of a child’s life. Recommendations for continued breastfeeding, in combination with appropriate complementary foods, range from at least 1 to 2 years, as long as desired by both the mother and child [1, 2]. However, epidemiological data show that few mothers breastfeed to 1 year. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2020 Breastfeeding Report Card, while 84% initiated breastfeeding, 58% were breastfeeding at 6 months postpartum, and only 35% were breastfeeding at 12 months [4]. Importantly, these low breastfeeding rates at 1 year persist despite high rates of intention to breastfeed. In the U.S., 80% of mothers intend to breastfeed in some capacity, and of those, more than 85% intend to exclusively breastfeed for at least 3 months; however, only one third (32%) of mothers achieve their intended breastfeeding goals [5].

Discrepancies between breastfeeding recommendations and actual breastfeeding duration have been explored. Reported barriers include: neonatal intensive care unit admission of the newborn, pain or discomfort when breastfeeding, difficulty with latching, concerns with adequate milk supply, lack of professional lactation support, employment circumstances, unaccommodating childcare environments, and unsupportive social and cultural norms [6,7,8,9]. These barriers are further complicated by mental health disorders, which are common during pregnancy and the first 12 months after childbirth [10,11,12]. Specifically, research suggests the prevalence of perinatal anxiety disorders is at least 17%, approximately 7–20% of mothers experience clinical depression at some time during the perinatal period [13, 14], and up to 1 in 3 (34%) mothers report experiencing childbirth trauma, often leading to postpartum depression [15] and post-traumatic stress disorder [16]. Given the high prevalence of mental health disorders within the perinatal period, maternal mental health has been considered an important underlying factor associated with barriers and reduced rates of breastfeeding intention, initiation, exclusivity, and continuation [10,11,12].

Research has consistently shown that maternal mental health disorders are associated with poorer breastfeeding outcomes. For example, prenatal anxiety is associated with reduced breastfeeding intention and postpartum anxiety is associated with reduced initiation, exclusivity, and duration of breastfeeding [17, 18]. In addition, childbirth trauma negatively affects initiation and continuation of breastfeeding [19, 20], and a strong association exists between perinatal depression and reduced breastfeeding intention, exclusivity, and duration [21]. Research has also shown that not engaging in breastfeeding or having a negative breastfeeding experience may increase the risk of postpartum depressive symptoms [22,23,24], while engaging in breastfeeding may protect against or ameliorate these symptoms [25, 26]. Given these associations, it has generally been accepted that the relationship between maternal mental health and breastfeeding is bidirectional, whereby mental health disorders may impede breastfeeding success and difficulty with or absence of breastfeeding may predict postpartum depression and anxiety [17, 21, 22, 24, 26]. Shared risk factors (e.g., self-efficacy, lack of social support, disrupted sleep) and overlapping neuroendocrine mechanisms (e.g., regulation of oxytocin, prolactin, serotonin, and cortisol) of mental health disorders and breastfeeding are thought to explain this bidirectional relationship [27, 28]. Therefore, it is important to consider both factors when examining the efficacy of interventions to improve these outcomes.

Indeed, many interventions have been developed and implemented to improve mental health or breastfeeding outcomes. However, to our knowledge, there are no published systematic reviews that examine the efficacy of behavioral interventions that focus on both maternal mental health and breastfeeding outcomes. Therefore, the purpose of this manuscript was to systematically review the literature on the efficacy of behavioral interventions which included outcomes of both maternal mental health (depression, anxiety, and childbirth trauma) and breastfeeding (intention, initiation, duration, exclusivity, knowledge, and self-efficacy). By examining behavioral interventions that assessed both outcomes, we may better understand the intersection of the two and determine intervention components that affect them. Since mental health and breastfeeding have not historically been studied together, gaining a better understanding of how they overlap may lend insight to a more wholistic approach to care, improving our understanding of how to create and reform best practices which can improve the short and long-term health of the mother, child, and family unit.

Methods

This systematic review was completed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines. Details of the protocol for this systematic review were registered on PROSPERO and can be accessed at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=224228 [29]. We used the Covidence [30] software to manage title and abstract screening, full-text screening, quality assessment, and data extraction processes. The team consisted of five reviewers (B.L., J.P., K.C., L.P., and M.C.W.). Throughout these processes, each publication was independently evaluated by two reviewers using the conventional double-screening method. When discrepancies arose, all reviewers met and came to a consensus.

Data sources and search methodology (identification)

Using an a priori research protocol, relevant articles were identified from PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, and PsycINFO from database inception to 3 March 2022, in consultation with a senior research librarian at the University of Illinois at Chicago. The general search terms used included variants of breastfeeding, depression, anxiety, and trauma. The full search strategy can be found in an additional file (see Additional file 1). The search terms were organized by database and included both database-specific Subject Heading and Keyword searches. A total of 6195 studies were identified using this search strategy.

Study selection (screening and eligibility)

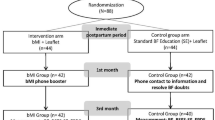

After automatic deduplication was completed in Covidence, a total of 3981 studies were available to be screened at the title and abstract level. For the purpose of this systematic review, empirical studies that assessed the effectiveness of behavioral interventions for improving maternal mental health and breastfeeding outcomes were included; the intervention itself did not have to focus on both factors, but inclusion of both outcomes was required. In this review, behavioral interventions, rather than medical, were included to home in on behavioral components that can be applied in future intervention efforts. Maternal mental health outcomes were depression, anxiety, and childbirth trauma. Various aspects of breastfeeding were considered, including intention, initiation, duration, exclusivity (feeding only human milk, not any other foods or liquids, except for medications or vitamin and mineral supplements), milk onset and volume, perceived milk supply, knowledge, and self-efficacy. Only articles available in English, those with primary experimental research design, and studies which used a behavioral intervention type were considered. Studies were included regardless of sample size or measurement type. A total of 135 full-text studies were assessed for eligibility, of which, 33 studies were included. A PRISMA flow diagram of the search strategy and study selection was generated (Fig. 1).

Quality assessment and data extraction

The quality of each study was independently assessed in Covidence using the Cochrane Risk of Bias [31] template. Risk was assessed for each publication by two independent reviewers for each of the following domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, and selective outcome reporting. Using an a priori data extraction protocol and the Covidence software, independent reviewers extracted pertinent data including authors and country, research design, participant characteristics (age, race/ethnicity, income, parity, mode of delivery, past breastfeeding experience, and mental health history), intervention description, breastfeeding outcomes (intention, initiation, duration, exclusivity, milk onset and volume, knowledge, self-efficacy), and mental health outcomes (depression, anxiety, childbirth trauma) when available. All results that were compatible with each outcome domain were sought. Although measure of effect varied for each study, we synthesized our main outcome (breastfeeding and mental health) results based on reported statistical significance (p < 0.05). No additional analyses (e.g., subgroup, sensitivity, certainty assessment) were performed.

Data synthesis

Relevant data from the final publications were extracted and organized in table format (Table 1). To examine the main outcomes, publications were synthesized by intervention success: 1. Successful interventions for mental health and breastfeeding outcomes, 2. Successful interventions for breastfeeding outcomes only, 3. Successful interventions for mental health outcomes only, and 4. Interventions with no effect. Within each of these sections of Table 1, publications were organized by the timing of the intervention (e.g., pregnancy, during the hospital stay at or around the time of birth, postpartum, and across both pregnancy and postpartum). When sample characteristics were not reported (NR), this was indicated.

Results

General description

A total of 33 articles met the criteria for inclusion in this review. Two articles [43, 44] describe data from the same study and an additional three articles describe data from another study [32,33,34], for a total of 30 unique interventions. Table 1 provides a summary of sample characteristics, intervention components, and mental health and breastfeeding outcomes of the studies included. Overall, 29 of the studies were randomized controlled trials (RCT) and one study used alternate-allocation for ‘randomization’ [41]. Studies were published between 1993 and 2022, with a majority (20/30, 67%) being published in the past 10 years.

Of the 30 interventions included in this review, eight were conducted in the U.S. [43, 44, 46, 50, 52, 58, 59, 61, 62], four in China [32,33,34, 36, 37, 54], three in Iran [47, 49, 57], two each from South Africa [53, 63], Spain [39, 51], and the United Kingdom [45, 56], and one each from Canada [35], Switzerland [60], Australia [41], Turkey [38], New Zealand [64], Nigeria [42], Mexico [48], Malaysia [55], and Croatia [40]. Of the eight studies conducted in the U.S., five (63%) had a sample primarily consisting of white non-Hispanic participants [43, 44, 50, 59, 61, 62], two studies had primarily Hispanic and/or Spanish-speaking participants [46, 58], and one study had primarily Black and Hispanic participants [52].

Sample size varied greatly across studies from 18 to 1324 participants. Eight interventions were conducted in first-time parents only [32,33,34, 37, 41, 45, 47, 49, 54, 55]. Five studies did not state the parity of the sample [38, 40, 57,58,59]. Fourteen of the studies did not report mode of birth as a sample characteristic. Three reported 100% of participants had a vaginal birth [39, 51, 61] and three reported 100% of participants had a cesarean birth [36, 37, 49]. Income level varied greatly among study samples and was reported differently from study to study, household vs. individual and annual vs. monthly. A total of 10 studies did not report income as a sample characteristic.

To examine the efficacy of these behavioral interventions on mental health and breastfeeding outcomes, results are presented and synthesized into four categories: 1. Successful interventions for mental health and breastfeeding outcomes, 2. Successful interventions for breastfeeding outcomes only, 3. Successful interventions for mental health outcomes only, and 4. Interventions with no effect. The intervention timing, method of intervention delivery, and design focus are presented in Table 1.

Successful interventions for mental health and breastfeeding outcomes

Twelve of the 30 studies reported statistically significant positive effect of the intervention on both maternal mental health and breastfeeding outcomes. Successful interventions included psychoeducational group programs [32,33,34, 41], relaxation therapy [40], skin-to-skin contact between mother and infant [35], psychological nursing [37], motivational interviewing [39], a health and infant care education program [36], stepped-care psychological treatment [42], peer support with home visits [45, 46], breastfeeding training with home visits [38], and risk-based treatment with home visits [43, 44].

Common characteristics among the successful interventions for mental health and breastfeeding outcomes were a) occurring across both pregnancy and the postpartum period (5/12, 42%) [41,42,43,44,45,46], b) delivered by hospital staff (3/12, 25%) [35,36,37] or by multidisciplinary teams of mental health and lactation specialists (3/12, 25%) [32,33,34, 41, 42], c) offered individually rather than in a group setting (9/12, 75%), and d) designed to focus on both breastfeeding and maternal mental health (5/12, 45%) [32,33,34, 38, 41, 43, 44, 46] or focused primarily on breastfeeding only (5/12, 45%) [35,36,37, 39, 40].

In regard to breastfeeding outcomes, eight studies reported breastfeeding exclusivity as an outcome and all eight indicated a statistically significant increase in exclusivity in the intervention group compared to the control, with assessment time points ranging from 3 days to 6 months postpartum [32,33,34,35,36, 38, 40,41,42, 46]. Breastfeeding duration was measured in eight studies, five of which indicated a statistically significant increase in duration at 3, 6, or 9 months postpartum in the intervention group compared to the control [35, 38,39,40, 43, 44]. Milk output/volume was measured in four studies and all four indicated a statistically significant increase in volume within the first 3 days to 2 weeks postpartum in the intervention group versus control [36, 37]. Initiation of breastfeeding was measured in four studies, three of which indicated a statistically significant increased rate of initiation among the intervention participants compared with control [32, 37, 44]. Breastfeeding self-efficacy was measured in four studies, two of which indicated a statistically significant enhanced self-efficacy between 3 days to 6 months postpartum in intervention versus control participants [32,33,34, 46]. Earlier milk onset [36], decreased breast swelling [36], greater levels of effective breastfeeding behavior (e.g., noticing changes in breast fullness, visualizing and hearing baby swallowing, etc.) [32,33,34] and increased mother-infant bonding [45] were reported among intervention versus control participants in these studies as well.

Regarding mental health outcomes, most studies reported depressive symptoms as an outcome (10/12, 83%). All (12/12, 100%) studies indicated a statistically significant decrease in the level of depressive symptoms at time points ranging from birth to 12 months postpartum among the intervention compared to the control participants. Although one study reported a decrease at 3 months postpartum, they showed more depressive symptoms at 30 months postpartum in the intervention group compared to control [44]. Symptoms of anxiety were measured in three studies and all reported lower levels across time points of 3 days to 6 months postpartum [36, 38, 40]. One study also reported a dose response of breastfeeding frequency, where the higher the frequency, the lower maternal anxiety levels became [38]. Stress was reported in one study and found lower levels of stress at 2 weeks and 2 and 6 months postpartum among the intervention participants [46].

Successful interventions for breastfeeding outcomes only

Six of the 30 studies reported statistically significant positive effect of the intervention on breastfeeding, but not maternal mental health outcomes. Successful interventions included doula support [48, 52], early hospital discharge with home-based postpartum care [51], massage therapy [49], an online interactive breastfeeding monitoring system with real-time support from a lactation specialist [50], and breastfeeding education group sessions [47].

Common characteristics among the successful interventions for breastfeeding outcomes only were a) occurring during the hospital stay at or around the time of birth (2/6, 33%) [48, 49] or during the postpartum period only (2/6, 33%) [50, 51], b) delivered by doulas (2/6, 33%) [48, 52], c) offered in an individual setting (5/6, 83%) [48,49,50,51,52], and d) designed to focus on both breastfeeding and maternal mental health (3/6, 50%) [48, 51, 52].

Two studies reported breastfeeding exclusivity as an outcome and both indicated a statistically significant increase in exclusivity in the intervention group compared to the control, with time points ranging from 1 to 3 months postpartum [48, 50]. Breastfeeding duration was measured in two studies, with one indicating a statistically significant increase in duration at 3 months postpartum among the intervention participants, but not at 1 week, one, six, or greater than 9 months postpartum [51]. The other study found no difference between groups for breastfeeding duration at 3 months postpartum [52]. Breastfeeding frequency was reported in two studies. One showed increased daily frequency status post cesarean birth [49] and the other from 1 to 3 months postpartum [50] among intervention versus control participants. Two studies measured breastfeeding knowledge and found an increase at time points ranging from birth to three months postpartum [47, 48]. Greater rate of breastfeeding initiation among intervention compared to control participants was found in one study [52].

Successful interventions for mental health outcomes only

Five of the 30 studies reported statistically significant positive effect of the intervention on maternal mental health, but not breastfeeding outcomes. Successful interventions included relaxation therapy [55], in-home postpartum support [56], prenatal psycho-educational group support [54], community health worker program plus incentive package [53], and journal therapy counseling [57].

Common characteristics among the successful interventions for mental health outcomes only were a) occurring during pregnancy only (2/5, 40%) [53, 54] or during the postpartum period only (2/5, 40%) [55, 56], b) delivered by research team members (3/5, 60%) [54, 55, 57], c) offered in an individual setting (3/5, 60%) [53, 55, 56], and d) designed to focus on both breastfeeding and maternal mental health (3/5, 60%) [53, 55, 56].

Three studies reported depressive symptoms as an outcome measured and each of these studies indicated a statistically significant decrease in the level of depressive symptoms at time points ranging from 1 week to 6 months postpartum among the intervention compared to the control participants [53, 54, 56]. Symptoms of anxiety were measured in two studies. One study reported a decrease at 2 weeks postpartum among intervention participants, but not at six and 12 weeks postpartum [55] and the other study reported a decrease at 2 and 4 months postpartum [57]. Stress was reported in one study using PSS and milk cortisol [55]. At 2 weeks postpartum, there were lower levels of stress as indicated by a decrease in hindmilk cortisol. Lower levels of stress were reported at six and 12 weeks postpartum according to the PSS among intervention participants [55].

Interventions with no effect

Of the 30 studies included in this review, seven reported no statistically significant difference between intervention and control groups for mental health and breastfeeding outcomes. These interventions included home-based postpartum care [60,61,62], in-home antenatal support [58], group prenatal care [59], sleep intervention [64], and audiovisual postpartum breastfeeding education [63]. Common characteristics among the interventions with no effect were a) occurring during the postpartum only (4/7, 57%) [60,61,62,63], b) delivered by home healthcare providers (2/7, 29%) [61, 62] or by perinatal care providers (2/7, 29%) [59, 60], c) offered in an individual setting (4/7, 57%) [58, 60, 62, 63], and d) designed to focus on both maternal mental health and breastfeeding (5/7, 71%) [58, 59, 61, 62, 64].

Risk of bias

The Cochrane Risk of Bias tool [31] was used to assess seven domains of bias (Table 2).

Random sequence generation (selection bias)

Adequate generation of a randomized sequence (low risk of selection bias) was described in 25 of the 30 RCTs. Two studies were at high risk for this bias [38, 59]. The method of randomization was not adequately described in three of the studies [40, 52, 58].

Allocation concealment (selection bias)

Adequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment (low risk of selection bias) was described in 19 of the 30 RCTs. Three studies were at high risk for this bias [35, 38, 53]. The method used to conceal the allocation sequence was not described in sufficient detail in eight of the studies.

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias)

Blinding was not always possible due to the nature of behavioral interventions. However, blinding of participants and personnel was ensured, or it was determined that the outcomes were not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding (low risk of performance bias) in 20 of the 30 RCTs. Four studies were at high risk for performance bias due to no or incomplete blinding [42, 53, 57, 58]. The method of blinding was not adequately described in six of the studies [40, 43,44,45, 47, 54, 63].

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias)

Blinding of the outcome assessment was ensured (low risk of detection bias) in 15 of the 30 RCTs. Two studies were at high risk for this bias [35, 36]. The method used to blind the outcome assessment was not described in sufficient detail in 13 of the studies.

Incomplete outcome data addressed (attrition bias)

The amount, nature, and handling of incomplete outcome data was appropriate (low risk of attrition bias) in 22 of the 30 RCTs. Four studies were at high risk for this bias [37, 41, 58, 63]. The method of blinding was not described in sufficient detail in four of the studies [36, 40, 47, 64].

Selective reporting (reporting bias)

Adequate description of the study’s pre-specified and expected outcomes (low risk of reporting bias) was provided in 22 of the 30 RCTs. Two studies were at high risk for this bias [47, 64]. This information was unclear or inadequate in six of the studies [38, 42, 49, 51, 52, 63].

Other sources of bias

Additional sources of potential bias assessed included protocol adherence, other interventions avoided, sample size sufficiently large, eligible participants enrolled, and funding and sponsorship bias. Low risk of other bias was found in 24 of the 30 RCTs. No studies were at high risk for this bias. This information was unclear or inadequate in six of the studies [37, 40, 43, 44, 49, 51, 58].

Discussion

This review examined 33 articles which sought to test the effect of 30 unique interventions on both maternal mental health and breastfeeding outcomes. Over one-third (12/30, 40%) of the interventions were successful at improving both mental health and breastfeeding outcomes, six (20%) reported positive effects on breastfeeding only, five (17%) reported positive effects on mental health only, and almost a quarter (7/30, 23%) of interventions had no effect on mental health or breastfeeding outcomes. Interventions that improved both mental health and breastfeeding outcomes were more likely to span across pregnancy and the postpartum period, including at or around birth, while interventions demonstrating no effect or an effect on only mental health or breastfeeding mostly occurred in either pregnancy or the postpartum period alone. Successful interventions were also more likely to be delivered by a combination of hospital staff, mental health and lactation specialists, and peer support. These findings are consistent with evidence indicating that support provided concurrently throughout a continuum of settings (e.g., health system, home, and community) results in the largest positive impact of breastfeeding outcomes [65]. Research also suggests that communication and collaboration between providers from various disciplines can improve both maternal mental health and breastfeeding outcomes [66].

Across all outcome categories, most (22/30, 73%) interventions took place in an individual rather than group setting. In a qualitative review of breastfeeding experiences among those with postpartum depression, mothers indicated that non-judgmental, encouraging, timely, and individualized support from professionals that are competent in breastfeeding counseling is essential in their decision and ability to breastfeed [24].

Consistent with evidence of a bidirectional association between maternal mental health and breastfeeding, most successful interventions in this review showed an increase in breastfeeding duration and/or exclusivity in parallel to a decrease in self-report depressive and/or anxiety symptoms. Shared neuroendocrine mechanisms between mental health and breastfeeding are thought to play a role. In normal physiological conditions, the lactogenic hormones oxytocin and prolactin have mood-ameliorating effects; promoting feelings of relaxation during breastfeeding [67]. Breastfeeding is thought to lessen the stress response and enhance maternal mood. In fact, research has shown that salivary and plasma cortisol response to stress is suppressed in lactating individuals in situations of physical and psychological stress [68]. However, disruptions in the homeostasis of lactogenic hormones (i.e., low levels) can affect mood and breastfeeding success. For instance, physical or emotional stress is known to increase levels of salivary and plasma cortisol [17, 28], and higher cortisol levels can interfere with the regulation of oxytocin and prolactin [28] and have been associated with decreased milk volume [17]. Consistent with this mechanism, one study in this review reported increased milk volume with concurrent reduced levels of stress or anxiety [36]. It is important to note that while perceived concern of milk supply is one of the most common factors associated with early breastfeeding cessation and postpartum anxiety [20, 69, 70], none of the studies in this review assessed perceived milk supply.

Although intervention strategies varied greatly across studies, most interventions with a positive effect on mental health and breastfeeding were designed to focus on mental health and breastfeeding (5/12, 42%) or breastfeeding alone (5/12, 42%). This suggests that intervening on breastfeeding alone may be similarly effective as intervening on mental health and breastfeeding to improve both outcomes. Perhaps by supporting the breastfeeding experience, we are supporting something more; we are supporting the whole person and their community.

Limitations

Several limitations of this review should be noted. First, after screening at the title and abstract phase, 3846 of the 3981 potentially eligible records were excluded indicating our search strategy may have been too broad. Next, the interventions took place across 15 different countries which makes it difficult to make direct comparisons given the varying policies and social environments that can affect maternal mental health and breastfeeding outcomes. Additionally, the majority (5/8, 63%) of U.S.-based samples in this review included white non-Hispanic participants only, making it difficult to consider the intersectional complexities of race, mental health, and breastfeeding. Future research must take an intersectional approach to understand how varying identities and compounding experiences of discrimination and oppression impact outcomes of mental health and breastfeeding. Previous breastfeeding experience, which could impact results, was only reported in four articles [39, 50, 61, 62]. In addition, parity was not consistent across studies and was not reported in many articles. Lactogenic hormone release is greater in multiparous mothers compared to primiparous, indicating that parity may be an important factor in the relationship between mental health and breastfeeding [25]. Many articles (21/30, 70%) did not report current or history of mental health difficulties within the study sample, which is a potential for unknown confounding. The varying follow-up time points and measurement strategies used across studies make it difficult to make direct comparisons as well. Next, childbirth experience continues to be underrepresented in the literature. Nearly half of the studies did not report mode of birth. Further, no studies were found examining childbirth-related trauma as an outcome. It is likely that the events that occur during labor and birth have an impact on breastfeeding outcomes, mostly due to the delay of lactogenesis II and the disruption of normal physiologic processes [71]. Childbirth trauma is also associated with increased risk of postpartum depression and post-traumatic stress disorder [15, 16]. Next. under- and over-nutrition may affect milk volume and composition. More specifically, there is data suggesting that obesity is associated with insufficient glandular development, reduced milk volume, dampened milk ejection reflex, suppressed lactation, and elevated depressive symptoms [71, 72], however, only four articles reported body mass index as a sample characteristic [39, 45, 49, 58]. Lastly, future research should examine how medications for mental health, in the presence and absence of behavioral intervention, may impact breastfeeding and mental health outcomes as well [73].

While not a limitation, it should be noted that only one intervention used digital-technology [50]. The Internet offers great potential in extending preventive services to individuals in the perinatal period since they address several key barriers to success such as limited access to professional support and lack of social support. Digital-technology interventions, which include the use of web-based content and interactions, text messaging, and social media, have been effective at reducing depressive symptoms and improving breastfeeding outcomes [24, 74]. Strengths of a digital approach to interventions for perinatal mothers include efficiency of time and resources, ability to reach geographically and racially diverse populations, and improved social support.

Conclusions

This systematic review highlights the intersection of maternal mental health and breastfeeding. Both occur in complex settings that affect and can be affected by physiological, emotional, social, psychological, personal, cultural, and physical factors. Based on this review, interventions that extend across pregnancy and postpartum and offer individualized support from both professionals and peers who collaborate through a continuum of settings are most successful in improving both mental health and breastfeeding outcomes. The benefits of improving these outcomes warrant continued development and implementation of interventions that acknowledge and support the whole person and their community.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RCT:

-

randomized controlled trials

- U.S.:

-

United States

References

NHMRC. Infant feeding guidelines - information for health workers; 2012.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk abstract; 2012. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-3552.

U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. 9th edition; 2020. Available at DietaryGuidelines.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding report card, United States, 2020 2020;2011. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/mpinc/index.htm. (Accessed 16 Aug 2020).

Perrine CG, Scanlon KS, Li R, Odom E, Grummer-Strawn LM. Baby-friendly hospital practices and meeting exclusive breastfeeding intention. Pediatrics. 2012;130:54–60. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-3633.

Jones KM, Power ML, Queenan JT, Schulkin J. Racial and ethnic disparities in breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10:186–96. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2014.0152.

Anstey EH, Chen J, Elam-Evans LD, Perrine CG. Racial and geographic differences in breastfeeding — United States, 2011–2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:723–7. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6627a3.

Wallwiener S, Müller M, Doster A, Plewniok K, Wallwiener CW, Fluhr H, et al. Predictors of impaired breastfeeding initiation and maintenance in a diverse sample: what is important? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;294:455–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-015-3994-5.

Gerd AT, Bergman S, Dahlgren J, Roswall J, Alm B. Factors associated with discontinuation of breastfeeding before 1 month of age. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101:55–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02405.x.

Carter D, Kostaras X. Psychiatric disorders in pregnancy. BC Med J. 2005;47:96–9.

Vesga-López O, Blanco C, Keyes K, Olfson M, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:805–15. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.805.

Lewis A, Austin E, Knapp R, Vaiano T, Galbally M. Perinatal maternal mental health, fetal programming and child development. Healthcare. 2015;3:1212–27. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare3041212.

O’Hara MW, Schlechte JA, Lewis DA, Varner MW. Controlled prospective study of postpartum mood disorders: psychological, environmental, and hormonal variables. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100:63–73. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.100.1.63.

Bennett HA, Einarson A, Taddio A, Koren G, Einarson TRT, Taddio A, et al. Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:698–709. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000116689.75396.5f.

Bell AF, Andersson E. The birth experience and women’s postnatal depression: a systematic review. Midwifery. 2016;39:112–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2016.04.014.

Ayers S. Delivery as a traumatic event: prevalence, risk factors, and treatment for postnatal posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2004;47:552–67.

Fallon V, Groves R, Halford JCG, Bennett KM, Harrold JA. Postpartum anxiety and infant-feeding outcomes: a systematic review. J Hum Lact. 2016;32:740–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334416662241.

Hoff CE, Movva N, Rosen Vollmar AK, Pérez-Escamilla R. Impact of maternal anxiety on breastfeeding outcomes: a systematic review. Adv Nutr. 2019;10:816–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmy132.

Beck CT, Watson S. Impact of birth trauma on breast-feeding: a tale of two pathways. Nurs Res. 2008;57:228–36. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nnr.0000313494.87282.90.

Garthus-Niegel S, Horsch A, Ayers S, Junge-Hoffmeister J, Weidner K, Eberhard-Gran M. The influence of postpartum PTSD on breastfeeding: a longitudinal population-based study. Birth. 2017;45:193–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12328.

Dias CC, Figueiredo B. Breastfeeding and depression: a systematic review of the literature. J Affect Disord. 2015;171:142–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.09.022.

Ystrom E. Breastfeeding cessation and symptoms of anxiety and depression: a longitudinal cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:36. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-12-36.

Dennis CL, McQueen K. Does maternal postpartum depressive symptomatology influence infant feeding outcomes? Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:590–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00184.x.

Da Silva TD, Bick D, Chang Y-SS. Breastfeeding experiences and perspectives among women with postnatal depression: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Women Birth. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2019.05.012.

Mezzacappa ES, Endicott J. Parity mediates the association between infant feeding method and maternal depressive symptoms in the postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10:259–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-007-0207-7.

Mezzacappa ES, Katkin ES. Breast-feeding is associated with reduced perceived stress and negative mood in mothers. Health Psychol. 2002;21:187–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.21.2.187.

Lara-Cinisomo S, McKenney K, Di Florio A, Meltzer-Brody S. Associations between postpartum depression, breastfeeding, and oxytocin levels in Latina mothers. Breastfeed Med. 2017;12:436–42. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2016.0213.

Stuebe AM, Grewen K, Pedersen CA, Propper C, Meltzer-Brody S. Failed lactation and perinatal depression: common problems with shared neuroendocrine mechanisms? J Women's Health. 2012;21:264–72. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2011.3083.

Pezley L, Cares K, Duffecy J, Koenig MD, Maki P, Odoms-Young A, et al. Efficacy of behavioral interventions to improve maternal mental health and breastfeeding outcomes: a systematic review. PROSPERO Int Prospect Regist Syst Rev. 2021;CRD4202122.

Covidence Systematic Review Software. Veritas health innovation; 2020. https://www.covidence.org/.

Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928.

Zhao Y, Lin Q, Wang J, Bao J. Effects of prenatal individualized mixed management on breastfeeding and maternal health at three days postpartum: a randomized controlled trial. Early Hum Dev. 2020;141:104944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2019.104944.

Zhao Y, Lin Q, Wang J. An evaluation of a prenatal individualised mixed management intervention addressing breastfeeding outcomes and postpartum depression: a randomised controlled trial. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30:1347–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15684.

Zhao Y, Lin Q, Zhu X, Wang J. Randomized clinical trial of a prenatal breastfeeding and mental health mixed management intervention. J Hum Lact. 2021;37:761–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334421991058.

Bigelow AE, Power M, Gillis DE, Maclellan-Peters J, Alex M, McDonald C. Breastfeeding, skin-to-skin contact, and mother-infant interactions over infants’ first three months. Infant Ment Health J. 2014;35:51–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21424.

Liu Y, Yao J, Liu X, Luo B, Zhao X. A randomized interventional study to promote milk secretion during mother–baby separation based on the health belief model. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12921. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000012921.

Song K, Wang J, Li Z. Positive effect of psychological nursing on the breastfeeding success rate of parturients who underwent caesarean section. Biomed Res. 2017;28:8336–9.

Çiftçi EK, Arikan D. The effect of training administered to working mothers on maternal anxiety levels and breastfeeding habits. J Clin Nurs. 2011;21:2170–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03957.x.

Franco-Antonio C, Santano-Mogena E, Chimento-Díaz S, Sánchez-García P, Cordovilla-Guardia S. A randomised controlled trial evaluating the effect of a brief motivational intervention to promote breastfeeding in postpartum depression. Sci Rep. 2022;12:373. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-04338-w.

Vidas M, Folnegovic-Smalc V, Catipovic M, Kisic M. The application of autogenic training in counseling center for mother and child in order to promote breastfeeding. Collegium Antropologicum. 2011;35:723–31.

Buultjens M, Murphy G, Milgrom J, Taket A, Poinen D. Supporting the transition to parenthood: development of a group health-promoting programme. Br. J Midwifery. 2018;26:387–97. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjom.2018.26.6.387.

Gureje O, Oladeji BD, Montgomery AA, Araya R, Bello T, Chisholm D, et al. High- versus low-intensity interventions for perinatal depression delivered by non-specialist primary maternal care providers in Nigeria: cluster randomised controlled trial (the EXPONATE trial). Br J Psychiatry. 2019;215:528–35. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.4.

Johnston BD, Huebner CE, Tyll LT, Barlow WE, Thompson RS. Expanding developmental and behavioral services for newborns in primary care. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26:356–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2003.12.018.

Johnston BD, Huebner CE, Anderson ML, Tyll LT, Thompson RS. Healthy steps in an integrated delivery system. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:793. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.160.8.793.

Kenyon S, Jolly K, Hemming K, Hope L, Blissett J, Dann S-A, et al. Lay support for pregnant women with social risk: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e009203. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009203.

Lutenbacher M, Elkins T, Dietrich MS, Riggs A. The efficacy of using peer mentors to improve maternal and infant health outcomes in Hispanic families: findings from a randomized clinical trial. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22:92–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2532-z.

Akbarzadeh M, Rad SK, Moattari M, Zare N. Investigation of breastfeeding training based on BASNEF model on the intensity of postpartum blues. East Mediterr Health J. 2017;23:830–5. https://doi.org/10.26719/2017.23.12.830.

Langer A, Campero L, Garcia C, Reynoso S. Effects of psychosocial support during labour and childbirth on breastfeeding, medical interventions, and mothers’ wellbeing in a Mexican public hospital: a randomised clinical trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:1056–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb09936.x.

Saatsaz S, Rezaei R, Alipour A, Beheshti Z. Massage as adjuvant therapy in the management of post-cesarean pain and anxiety: a randomized clinical trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2016;24:92–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2016.05.014.

Ahmed AH, Roumani AM, Szucs K, Zhang L, King D. The effect of interactive web-based monitoring on breastfeeding exclusivity, intensity, and duration in healthy, term infants after hospital discharge. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2016;45:143–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogn.2015.12.001.

Sainz Bueno JA, Romano MR, Teruel RG, Benjumea AG, Palacín AF, González CA, et al. Early discharge from obstetrics-pediatrics at the hospital de Valme, with domiciliary follow-up. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:714–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2005.01.015.

Hans SL, Edwards RC, Zhang Y. Randomized controlled trial of doula-home-visiting services: impact on maternal and infant health. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22:105–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2537-7.

Rossouw L, Burger RP, Burger R. Testing an incentive-based and community health worker package intervention to improve maternal health and nutrition outcomes: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Matern Child Health J. 2021;25:1913–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-021-03229-w.

Zhao Y, Munro-Kramer ML, Shi S, Wang J, Luo J. A randomized controlled trial: effects of a prenatal depression intervention on perinatal outcomes among Chinese high-risk pregnant women with medically defined complications. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20:333–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-016-0712-7.

Mohd Shukri NH, Wells J, Eaton S, Mukhtar F, Petelin A, Jenko-Pražnikar Z, et al. Randomized controlled trial investigating the effects of a breastfeeding relaxation intervention on maternal psychological state, breast milk outcomes, and infant behavior and growth. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;110:121–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqz033.

Morrell CJ. Costs and effectiveness of community postnatal support workers: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2000;321:593–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.321.7261.593.

Montazeri M, Mirghafourvand M, Esmaeilpour K, Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi S, Amiri P. Effects of journal therapy counseling with anxious pregnant women on their infants’ sleep quality: a randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20:229–41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02132-7.

Rotheram-Fuller EJ, Swendeman D, Becker KD, Daleiden E, Chorpita B, Harris DM, et al. Replicating evidence-based practices with flexibility for perinatal home visiting by paraprofessionals. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21:2209–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-017-2342-8.

Tubay AT, Mansalis KA, Simpson MJ, Armitage NH, Briscoe G, Potts V. The effects of group prenatal care on infant birthweight and maternal well-being: a randomized controlled trial. Mil Med. 2019;184:e440–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usy361.

Boulvain M, Perneger TV, Othenin-Girard V, Petrou S, Berner M, Irion O. Home-based versus hospital-based postnatal care: a randomised trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;111:807–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00227.x.

Escobar GJ, Braveman PA, Ackerson L, Odouli R, Coleman-Phox K, Capra AM, et al. A randomized comparison of home visits and hospital-based group follow-up visits after early postpartum discharge. Pediatrics. 2001;108:719–27. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.108.3.719.

Lieu T, Braveman P, Escobar G, Fischer A, Jensvold N, Capra A. A randomized comparison of home visits and hospital-based group follow-up visits after early postpartum discharge. Pediatrics. 2000;108:719–27. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.108.3.719.

Nikodem VC, Hofmeyr GJ, Kramer TR, Gülmezoglu AM, Anderson A. Audiovisual education and breastfeeding practices: a preliminary report. Curationis. 1993;16:60–3. https://doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v16i4.1418.

Galland BC, Sayers RM, Cameron SL, Gray AR, Heath A-LM, Lawrence JA, et al. Anticipatory guidance to prevent infant sleep problems within a randomised controlled trial: infant, maternal and partner outcomes at 6 months of age. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014908. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014908.

Sinha B, Chowdhury R, Sankar MJ, Martines J, Taneja S, Mazumder S, et al. Interventions to improve breastfeeding outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104:114–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.13127.

Bunik M, Dunn DM, Watkins L, Talmi A. Trifecta approach to breastfeeding: clinical care in the integrated mental health model. J Hum Lact. 2014;30:143–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334414523333.

Skalkidou A, Hellgren C, Comasco E, Sylvén S, Sundström PI. Biological aspects of postpartum depression. Women's Health (Lond Engl). 2012;8:659–72. https://doi.org/10.2217/whe.12.55.

Heinrichs M, Meinlschmidt G, Neumann I, Wagner S, Kirschbaum C, Ehlert U, et al. Effects of suckling on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis responses to psychosocial stress in postpartum lactating women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:4798–804. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.86.10.7919.

Lewallen LP, Dick MJ, Flowers J, Powell W, Zickefoose KT, Wall YG, et al. Breastfeeding support and early cessation. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35:166–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00031.x.

Amir LH, Cwikel J. Why do women stop breastfeeding? A closer look at “not enough milk” among Israeli women in the Negev region. Breastfeed Rev. 2005;13:7–14.

Sriraman NK. The nuts and bolts of breastfeeding: anatomy and physiology of lactation. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2017;47:305–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2017.10.001.

Molyneaux E, Poston L, Ashurst-Williams S, Howard LM. Obesity and mental disorders during pregnancy and postpartum: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:857–67. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000170.

Jordan S, Davies GI, Thayer DS, Tucker D, Humphreys I. Antidepressant prescriptions, discontinuation, depression and perinatal outcomes, including breastfeeding: a population cohort analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0225133. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225133.

Andersson G, Cuijpers P. Internet-based and other computerized psychological treatments for adult depression: a meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;38:196–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070903318960.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like thank University of Illinois at Chicago Senior Research Librarian, Amelia Brunskill, for their collaboration on the protocol development and search methodology of this manuscript.

Funding

The authors have no funding information to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LP conceptualized the project. LP, LTH, JD, and JB developed the methodology. LP, KC, MCW, BL, and JP conducted study screening and eligibility processes, quality assessment, and data extraction. LTH, JD, MDK, and JB provided additional support for study selection and quality assessment. LP, KC, and MLO completed data synthesis and visualization. LP wrote the original draft of the manuscript. All authors read, provided valuable edits, and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

LP, PhD, MS, RDN; KC, MS, RDN; JD, PhD; MDK, PhD, RN, CNM; PM, PhD; AOY, PhD; MHCW, MA; MLO, MS, RD; BL, MA; JP, MS, RDN; LTH, PhD, MS, RD; JB, PhD.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Search Strategy. Search terms used in PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, and PsycINFO.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pezley, L., Cares, K., Duffecy, J. et al. Efficacy of behavioral interventions to improve maternal mental health and breastfeeding outcomes: a systematic review. Int Breastfeed J 17, 67 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-022-00501-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-022-00501-9