Abstract

Background

Preeclampsia is a global health problem and it is the main cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality. Breastfeeding has been reported to be associated with lower postpartum blood pressure in women with gestational hypertension. However, there is no published data on the role that breastfeeding might play in preventing preeclampsia. The aim of the current study was to investigate if breastfeeding was associated with preeclampsia in parous women.

Method

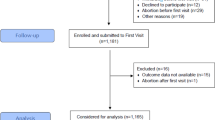

A case-control study was conducted in Saad Abualila Maternity Hospital in Khartoum, Sudan, from May to December 2019. The cases (n = 116) were parous women with preeclampsia. Two consecutive healthy pregnant women served as controls for each case (n = 232). The sociodemographic, medical, and obstetric histories were gathered using a questionnaire. Breastfeeding practices and duration were assessed.

Results

A total of 98 (84.5%) women with preeclampsia and 216 (93.1%) women in the control group had breastfed their previous children. The unadjusted odds ratio (OR) of preeclampsia (no breastfeeding vs breastfeeding) was 3.55, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.64,7.70 and p value = 0.001 based on these numbers. After adjusting for age, parity, education level, occupation, history of preeclampsia, history of miscarriage, body mass index groups the adjusted OR was 3.19, 95% CI 1.49, 6.82 (p value = 0.006).

Conclusion

Breastfeeding might reduce the risk for preeclampsia. Further larger studies are required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Preeclampsia is characterized by new-onset hypertension and proteinuria after the 20th week of gestation, and it is one of the main pregnancy-related disorders [1]. It has been estimated that approximately 2–8% of pregnant/parturient women worldwide have preeclampsia [2]. Preeclampsia is a main cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality [2]. The function of multiple systems and organs, such as the liver, kidneys, and brain, can be affected by preeclampsia [2]. The exact aetiology and pathophysiology of preeclampsia are not well understood; however, several risk factors (parity, body mass index (BMI), chronic disease, lack of antenatal care, and anaemia) have been identified as risk factors and can be used as predictors of preeclampsia [3].

Breastfeeding is globally considered a vital public health issue with social, religious, and economic implications [4, 5]. Breastfeeding is associated with reduced negative cardiovascular sequelae that are attributed to preeclampsia (hypertension, type II diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease) [6]. It has recently been shown that women who had normotensive pregnancies and breastfed were at a lower risk of atherosclerosis than peers who had never breastfed [7]. It has been shown that breastfeeding is associated with lower blood pressure in later life [8]. Moreover, breastfeeding was reported to be associated with lower postpartum blood pressure in women with normal weight [9] and in women with gestational hypertension [10]. To the best of our knowledge, there is no published data on the role that breastfeeding might play in preventing preeclampsia. Hence, this study was conducted in Khartoum, Sudan, to investigate if breastfeeding was associated with preeclampsia in parous women. Preeclampsia is the leading cause of poor maternal and perinatal outcomes in Sudan [11]. We have previously showed that several clinical, biochemical, and genetic factors are associated with preeclampsia [12,13,14,15,16]. However, the real effects of breastfeeding in reducing the risk of preeclampsia remain debated.

Methods

A case-control study was conducted in Saad Abualila Maternity Hospital in Khartoum, Sudan, from May to December 2019. The cases were parous women with preeclampsia recruited from the labour ward. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists criteria [1] were used to diagnose preeclampsia as follows: pregnant women with a blood pressure equal to or greater than 140/90 mmHg on two occasions at least 6 h apart plus proteinuria (≥ 300 mg/24 h). Women with a blood pressure ≥ 160/110 mmHg on two occasions, proteinuria of ≥5 g/24 h, and HELLP syndrome (haemolytic anaemia, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count) were considered to have severe preeclampsia, otherwise, preeclampsia was considered mild [1]. Women who presented with preeclampsia before and after 34 weeks were classified as having early-onset and late-onset preeclampsia, respectively [17]. Two consecutive healthy pregnant women without any underlying diseases, such as hypertension, renal disease, diabetes, or proteinuria, served as controls for each case. Women with multiple pregnancies or other comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus, renal disease, thyroid disease, major foetal anomalies, foetal demise, and haemolytic disease, were excluded from the study.

After providing an informed consent, women (in the case and control groups) were asked about their age, parity, educational level, antenatal attendance, interpregnancy interval (IPI), history of miscarriage, and history of preeclampsia/hypertension in previous pregnancies. Pre-pregnancy or first-trimester weight and height were used to compute the BMI as weight/height2. The BMI was classified per the World Health Organization classification for BMI [18] as follows: normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2), or obese (30.0–34.9 kg/m2). The haemoglobin concentration (at delivery) and blood group were recorded. Following delivery, the gender of the newborn was recorded.

To assess breastfeeding practices and duration, women were initially asked “Did you breastfeed your last baby?” Women who answered “no” were categorized as never breastfed.

The sample included 116 cases and 232 controls (ratio of 1:2). The sample size was calculated based on the report on breastfeeding (87.2% of women initiated breastfeeding within the first hour) in eastern Sudan [19]. We assumed that 85% of the cases (preeclampsia) vs 95% of the controls had breastfed their babies (regardless of the duration of breastfeeding). This sample size would result in 80% power with a precision of 5% to detect a difference of 10% in breastfeeding rates (95% vs 85%) between mothers with and without preeclampsia.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Proportions of the studied variables were expressed as the frequency (%). Continuous data were evaluated for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The variables; age, parity, education level, occupation, history of preeclampsia, history of miscarriage, and BMI were included in the multivariate logistic regression adjusting for possible confounding of the relationship between previous breastfeeding and preeclampsia. All of these variables were included in the regression (i.e. no backward elimination). Some variables such as IPI, blood group, antenatal care, haemoglobin level at delivery, and gender of infant were not included as confounding factors because these variables occurred after the previous breastfeeding. Even if these variables are related to preeclampsia, they are not confounders of the relationship between previous breastfeeding and preeclampsia because they are on the causal pathway. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

There was no significant difference in the sociodemographic and clinical variables between women who breastfed (n = 314) and women who did not breastfeed (n = 34) in previous pregnancy (Table 1).

Table 2 shows comparisons of the sociodemographic variables between women with preeclampsia (n = 116) and the controls (n = 232). Age and parity were significantly higher in women with preeclampsia. More women with preeclampsia were employed and breastfed. There were no significant differences in the educational level, antenatal care attendance, IPI, history of preeclampsia, history of miscarriage, BMI, haemoglobin level, or blood group of the mother or gender of the newborn between the groups. The median (interquartile range) of the duration of breastfeeding in those who breastfed (i.e., excluding those who did not breastfeed) was 4.0 (2.0) months. Among the 116 women with preeclampsia, 26 (22.4%) and 8 (6.8%) had severe and early-onset preeclampsia, respectively.

A total of 98 (84.5%) women with preeclampsia and 216 (93.1%) women in the control group had breastfed their previous children. The unadjusted odds ratio (OR) is 3.55; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.64, 7.70. After adjusting for age, parity, education level, occupation, history of preeclampsia, history of miscarriage, BMI groups the adjusted OR is 3.19; 95% CI 1.49, 6.82 (Table 3).

Discussion

The main findings of the current study were as follows: compared with women who had breastfed their previous children, women who had not previously breastfed had a higher risk of preeclampsia (Adjusted OR 3.19; 95% CI 1.49, 6.82). A previous study showed that in normal-weight women, breastfeeding was associated with lower blood pressure 1 month after delivery [9]. In a meta-analysis, which included 255,271 women, Rameez et al. reported that breastfeeding for > 2 months was associated with a relative risk reduction of 13% (pooled OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.78, 0.97] for hypertension [20]. Zang et al. reported that women who breastfed for 0–6 months, 6–12 months, and > 12 months had a 13, 17, and 21% lower risk of hypertension, respectively, compared to women who did not breastfeed [21]. Schwarz et al. showed that women who breastfed > 12 months had a lower risk (12% lower risk) of hypertension than women who never breastfed [22]. Likewise, another study showed a lower risk of hypertension in women who breastfed for > 6 months compared with parous women who did not breastfeed [23]. Countouris et al. reported that breastfeeding was not associated with postpartum blood pressure in women with preeclampsia or in those who were normotensive during pregnancy [10].

The exact mechanisms of the association between hypertension and breastfeeding remain unknown. However, it is known that lactation improves the cardiometabolic risk profile [24,25,26]. Breastfeeding has been reported to be associated with less postpartum weight retention in mothers who had a normal weight before pregnancy [27]. Moreover, a favourable cardiometabolic profile and decreased risk of atherosclerosis have been reported in women with a history of normotensive pregnancies who breastfed for any duration compared with women who did not breastfeed [7]. In a meta-analysis, Nguyen and Ding reported protective effects of breastfeeding on cardiovascular health (metabolic syndrome, inflammatory markers, hypertension and cardiovascular disease) [28]. A previous animal study showed that at 9 months post-delivery, non-lactating mice had a significantly lower cardiac output, ejection fraction, fasting glucose level, and low-density lipoprotein level [26]. In addition, breastfeeding may affect factors that influence systolic blood pressure (arterial stiffness and compliance) [29].

Breastfeeding affects several hormones, such as oxytocin [30], prolactin [31], cortisol [32], oestrogen, and progesterone, which might impact blood pressure. Hormonal pathways (specifically oxytocin) may lower postpartum blood pressure by decreasing inflammatory markers [30]. In the central nervous system, mainly in the vagal nuclei and the locus coeruleus, oxytocin might interact with nitric oxide and atrial natriuretic peptide and lower blood pressure [33]. Ghrelin, a hormone that affects appetite and is associated with breastfeeding, can reduce the risk of metabolic diseases [34, 35]. Moreover, obesity and obesity-associated hypertension may be the result of insulin sensitivity [36].

Limitations

One of the limitations of the current study was that it only investigated the association between breastfeeding and preeclampsia in parous women. As was expected, it was not possible to include primiparous women because they did not have previous baby or had breastfed. A recent meta-analysis showed that primigravidae were associated with preeclampsia [3]. Another limitation was the report of a history of breastfeeding depended on women’s memories, and thus, bias was expected. However, reliable and valid results have been reported with the recall of breastfeeding [37]. It is obvious that the current study was designed and the sample size was calculated for breastfeeding or not and it was not calculated for the duration of the breastfeeding. Hence it lacks the power for the association between preeclampsia and the duration of breastfeeding.

Conclusion

Breastfeeding might reduce the risk for preeclampsia. Further larger studies are needed.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- LR:

-

Likelihood ratio

References

ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG practice bulletin. Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia. Number 33, January 2002. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;77:67–75.

Abalos E, Cuesta C, Grosso AL, Chou D, Say L. Global and regional estimates of preeclampsia and eclampsia: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;170(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.05.005.

Meazaw MW, Chojenta C, Muluneh MD, Loxton D. Systematic and meta-analysis of factors associated with preeclampsia and eclampsia in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0237600. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237600.

The World Health Organization, Report of the expert consultation of the optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding, Geneva 2001. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/67219/WHO_NHD_01.09.pdf. Acessed 23 Feb 2021.

Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and obesity. Breastfeeding report card, progressing toward national breastfeeding Goals. United States; 2016. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/pdf/2016breastfeedingreportcard.pdf. Acessed 23 Feb 2021

Perrine CG, Nelson JM, Corbelli J, Scanlon KS. Lactation and maternal cardio-metabolic health. Annu Rev Nutr. 2016;36(1):627–45. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nutr-071715-051213.

Countouris ME, Holzman C, Althouse AD, Snyder GG, Barinas-Mitchell E, Reis SE, et al. Lactation and maternal subclinical atherosclerosis among women with and without a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Womens Health (Larchmt). 2020;29(6):789–98. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2019.7863.

Stuebe AM, Schwarz EB, Grewen K, Rich-Edwards JW, Michels KB, Foster EM, et al. Duration of lactation and incidence of maternal hypertension: a longitudinal cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(10):1147–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwr227.

Kashiwakura I, Ebina S. Influence of breastfeeding on maternal blood pressure at one month postpartum. Int J Women's Health. 2012;4:333.

Countouris ME, Schwarz EB, Rossiter BC, Althouse AD, Berlacher KL, Jeyabalan A, et al. Effects of lactation on postpartum blood pressure among women with gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:241.e1–8.

Ali AA, Okud A, Khojali A, Adam I. High incidence of obstetric complications in Kassala Hospital, Eastern Sudan. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;32(2):148–9. https://doi.org/10.3109/01443615.2011.637140.

Saad A, Adam I, Elzaki SEG, Awooda HA, Hamdan HZ. Leptin receptor gene polymorphisms c.668A>G and c.1968G>C in Sudanese women with preeclampsia: a case-control study. BMC Med Genet. 2020;21:162.

Elhaj ET, Adam I, Alim A, Elhassan EM, Lutfi MF. Thyroid function/antibodies in Sudanese patients with preeclampsia. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2015;6:87.

Elmugabil A, Hamdan HZ, Elsheikh AE, Rayis DA, Adam I, Gasim GI. Serum calcium, magnesium, zinc and copper levels in Sudanese women with preeclampsia. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0167495. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167495.

Ahmed MA, Hassan NG, Omer ME, Rostami A, Rayis DA, Adam I. Helicobacter pylori and chlamydia trachomatis in Sudanese women with preeclampsia. J Matern Neonatal Med. 2020;33(12):2023–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2018.1536738.

Alshareef SA, Eltom AM, Nasr AM, Hamdan HZ, Adam I. Rubella, herpes simplex virus type 2 and preeclampsia. Virol J. 2017;14(1):142.

Tranquilli AL, Brown MA, Zeeman GG, Dekker G, Sibai BM. The definition of severe and early-onset preeclampsia. Statements from the International Society for the Study of hypertension in pregnancy (ISSHP). Pregnancy Hypertens. 2013;3(1):44–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preghy.2012.11.001.

Ota E, Haruna M, Suzuki M, Anh DD, Tho le H, Tam NT, et al. Maternal body mass index and gestational weight gain and their association with perinatal outcomes in Viet Nam. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(2):127–36. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.10.077982.

Hassan AA, Taha Z, Ahmed MAA, Ali AAA, Adam I. Assessment of initiation of breastfeeding practice in Kassala, Eastern Sudan: a community-based study. Int Breastfeed J. 2018;13:34.

Rameez RM, Sadana D, Kaur S, Ahmed T, Patel J, Khan MS, et al. Association of maternal lactation with diabetes and hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1913401. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13401.

Zhang BZ, Zhang HY, Liu HH, Li HJ, Wang JS. Breastfeeding and maternal hypertension and diabetes: a population-based cross-sectional study. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10(3):163–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2014.0116.

Schwarz EB, Ray RM, Stuebe AM, Allison MA, Ness RB, Freiberg MS, et al. Duration of lactation and risk factors for maternal cardiovascular disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(5):974–82. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000346884.67796.ca.

Lupton SJ, Chiu CL, Lujic S, Hennessy A, Lind JM. Association between parity and breastfeeding with maternal high blood pressure. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208:454.e1–7.

La Rosa M, Kechichian T, Olson G, Saade G, Bytautiene Prewit E. Lactation leads to modifications in maternal renin-angiotensin system in later life. Reprod Sci. 2020;27(1):260–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43032-019-00018-3.

Murata K, Saito C, Ishida J, Hamada J, Sugiyama F, Yagami KI, et al. Effect of lactation on postpartum cardiac function of pregnancy-associated hypertensive mice. Endocrinology. 2013;154(2):597–602. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2012-1789.

Herrera SR, Vincent KL, Poole A, Olson G, Patrikeev I, Saada J, et al. Long-term effect of lactation on maternal cardiovascular function and adiposity in a murine model. Am J Perinatol. 2019;36(5):490–7. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1669443.

Coitinho DC, Sichieri R, D’Aquino Benício MH. Obesity and weight change related to parity and breast-feeding among parous women in Brazil. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4(4):865–70. https://doi.org/10.1079/PHN2001125.

Nguyen B, Jin K, Ding D. Breastfeeding and maternal cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0187923. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187923.

Poole AT, Vincent KL, Olson GL, Patrikeev I, Saade GR, Stuebe A, et al. Effect of lactation on maternal postpartum cardiac function and adiposity: a murine model. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(4):424.e1–7.

Gutkowska J, Jankowski M. Oxytocin revisited: its role in cardiovascular regulation. J Neuroendocrinol. 2012;24(4):599–6088. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02235.x.

Stamatelopoulos KS, Georgiopoulos GA, Sfikakis PP, Kollias G, Manios E, Mantzou E, et al. Pilot study of circulating prolactin levels and endothelial function in men with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24(5):569–73. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajh.2011.16.

Ozarda Y, Gunes Y, Tuncer GO. The concentration of adiponectin in breast milk is related to maternal hormonal and inflammatory status during 6 months of lactation. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2012;50:911–7.

Petersson M. Cardiovascular effects of oxytocin. Prog Brain Res. 2002;139:281–8.

Öner-Iyidoǧan Y, Koçak H, Gürdöl F, Öner P, Işsever H, Esin D. Circulating ghrelin levels in obese women: a possible association with hypertension. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2007;67(5):568–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365510701210186.

Mao Y, Tokudome T, Kishimoto I. Ghrelin and blood pressure regulation. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2016;18(2):15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-015-0622-5.

Kotsis V, Stabouli S, Papakatsika S, Rizos Z, Parati G. Mechanisms of obesity-induced hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2010;33(5):386–93. https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2010.9.

Li R, Scanlon KS, Serdula MK. The validity and reliability of maternal recall of breastfeeding practice. Nutr Rev. 2005;63(4):103–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2005.tb00128.x.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IA, DAR and MIE conceived and designed the study. IA, DAR, NAA recruited the participants. IA, NAA, ABAA and MES analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All contributed authors of this original manuscript authorized the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study received exempt approval by the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the Faculty of Medicine University of Khartoum, Sudan (# 2018, 012). All women provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Adam, I., Rayis, D.A., ALhabardi, N.A. et al. Association between breastfeeding and preeclampsia in parous women: a case –control study. Int Breastfeed J 16, 48 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-021-00391-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-021-00391-3