Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) encourages early initiation of breastfeeding within the first hour after birth with the objective of saving children’s lives. There are few published research papers about factors associated with the initiation of breastfeeding in Sudan.

The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of and factors associated with the timely initiation of breastfeeding among mothers with children two years and under in Kassala, Eastern Sudan.

Methods

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted from December 2016 to March 2017. Mothers were interviewed using a structured questionnaire.

Results

A total of 250 mother-child pairs participated in the study. The mean (standard deviation) of maternal age and children’s age was 27.1 (5.68) years and 11.9 (6.9) months, respectively.

Of the 250 mothers, 218 (87.2%) initiated breastfeeding within the first hour. In multivariable logistic regression analysis, factors associated with the delay of breastfeeding initiation were having a male baby (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR] 3.90, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]1.33, 11.47), and mothers with medical disorders (AOR 5.07, 95% CI 1.22, 21.16).

Conclusion

There was a high prevalence of early initiation of breastfeeding. An association with delayed initiation of breastfeeding was found amongst mothers who had medical disorders and those who had a male infant. Wherever possible, early initiation of breastfeeding should be promoted for all infants, regardless of gender.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

According to the United Nations Children’s’ Fund (UNICEF) [1], the first 1000 days of a child’s life (9 months of pregnancy plus the first 2 years of life) is considered to be a crucial period. In countries with fewer resources such as Sudan, children two years and under are the most vulnerable in terms of morbidity and mortality [2, 3]. These children are vulnerable to malnutrition, gastroenteritis and respiratory tract infections [2,3,4,5,6]. A study published in 2015 documented high rates of malnutrition among children in Khartoum who were either not breastfed or were weaned early [6]. The children of Kassala are categorized as among the most vulnerable in Sudan where high rates of acute and chronic malnutrition were reported, especially among children [7]. The main reported causes of childhood hospitalisation in previous studies which include Sudan were respiratory tract infections and gastroenteritis [2, 8,9,10,11,12]. Predictors of hospital admission were identified as non-exclusive breastfeeding, delayed initiation of breastfeeding, maternal unemployment, having two or more children, complementary feeds given by a person other than the mother, prolonged rupture of membranes, home delivery, intrapartum fever, and Apgar score < 7 at 5 min [2, 8,9,10,11,12,13]. Likewise, early initiation of breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding are documented as key predictors of infant survival [14, 15].

Aiming to save children’s lives, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed a set of recommendations, including: Skin-to-skin’ at or as soon as possible after the birth, and unrestricted access to the breast thereafter to enhance the initiation of breastfeeding and the establishment of an adequate milk supply [16]. The WHO rated initiation of breastfeeding based on the percentage of babies breastfed within one hour of birth as follows: (0–29%), (30–49%), (50–89%), (90–100%) to poor, fair, good and very good, respectively [17]. Varying rates of initiation of breastfeeding were 17.7 and 98.4% [18,19,20,21,22].

Early initiation of breastfeeding promotes exclusive breastfeeding by enhancing bonding, increasing the likelihood of breastfeeding success, and generally extending breastfeeding duration [16, 17, 23].

Poor breastfeeding practices such as delayed initiation, low rates of exclusivity, and early weaning have been documented in previous studies undertaken in different regions of Sudan including Kassala [5, 24,25,26]. In addition to more recent reports these practices have been noted previously. A 1993 publication identified one urban and rural community study including the eastern region of Sudan where 27.1% of mothers weaned their infants before 12 months [27].

Although many studies in Sudan identify delayed breastfeeding initiation [19, 28], none report the factors associated with initiation of breastfeeding. Moreover, most of the available data about breastfeeding in Sudan is hospital-based [4, 27, 28] Investigating initiation of breastfeeding at community-level would help identify the factors which lead to early weaning and delayed breastfeeding initiation. Community based research is more efficient in yielding data needed for future community-based interventions.

The aim of this study is to investigate the prevalence of breastfeeding initiation and associated factors among mothers of infants aged two and under in Kassala, Eastern Sudan.

Methods

A two-stage random cluster study was conducted in Kassala, Eastern Sudan between December 2016 and March 2017. Stage one, simple random sampling of the localities was performed to randomly identify households. Similarly, stage two, random sampling of the household was used to identify participants (children aged two years or less). Kassala has an estimated population of 453,159 inhabitants of which 55% live in urban areas, with 33,604 and 52,853 households in urban and rural areas, respectively [29]. Houses were mapped to select a representative sample. The main tool used to collect data in this study was a structured questionnaire. Three female medical officers were trained by the investigators to collect the data. Before data collection the questionnaire was tested among 10 mothers (not included in the final sample) and the necessary corrections were done. The following inclusion criteria were set before conducting the study: willingness to participate, having a child of two years or younger (where there were two children aged two or younger, the interview was based on the youngest child), and availability at the time of data collection.

The time for the initiation of breastfeeding was measured by asking the mother about the time at which her current child was put to the breast after delivery (within one hour or more than one hour of delivery) [16, 19]. Initiation of breastfeeding with one hour or more than one hour was considered as early and delayed initiation respectively. The questionnaire was coded with the outcome variable (initiation of breastfeeding) as (0) and (1) for early and delayed initiation of breastfeeding, respectively.

Eligible participants were approached and the purpose of the study explained. Participants signed the study consent form after assurance was provided regarding the confidentiality of any information gained and the right to withdraw at any time clarified. After the participant’s acceptance and fulfilment of the study inclusion criteria, a face-to-face interview was conducted using a structured questionnaire.

The questionnaire included demographic information (maternal age, education, occupation), place of delivery (home, institutional) mode of delivery (vaginal delivery, caesarean delivery), and medical disorders such as diabetes in pregnancy, hypertension in pregnancy and asthma, delivery details; infant information (e.g. age in months, gender, child order, history of hospitalization, and the main reason for hospitalization.

Breastfeeding information about the index child was collected (e.g. initiation of breastfeeding, breastfeeding difficulty, etc.).

The calculated sample size was 250 participants using an assumption of 79.6% prevalence of early initiation of breastfeeding [30]. This sample was selected to give 80% power with a precision of 5%.

Statistical analysis

After the data were collected, the questionnaires were checked and all participants (n = 250) found to have complete data. Data were entered into the computer using Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS0 version 20.0 for Windows) and double checked before analysis. The results were illustrated in tables and text calculating the means and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables, frequencies and percentages for categorical variables to describe participant response. T-test and Chi-square test were applied to analyse continuous and categorical data, respectively. Variables with P-value of < 0.2 in univariate analysis were entered in multivariable logistic analysis with delayed initiation of breastfeeding as the dependent variable and the other variables such as age, birth order, education, residence, maternal medical disorders, mode of delivery, child gender, etc. as the independent variables. Odds Ratio (OR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) were calculated. P-value < 0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

A total of 250 mother-child pairs participated in the study. The mean (SD) of maternal and infant age was 27.1 (5.68) years and 11.9 (6.9) months, respectively. Maternal age ranged from 13 to 40 years and 40 (16%) of the women were ≤ 20 years. Twenty seven percent of participants were primiparous.

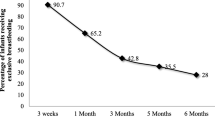

Of the 250 participants, 218 (87.2%) initiated breastfeeding within the first hour of delivery. Of 218 mothers who initiated breastfeeding within 1 h, 165 (66%) did so immediately and the remainder 53 (21.2%) within 1 h.

Only 11.2% (28/250) of the mothers were employed (government employed (n = 26), private (n = 1), own business (n = 1)). Almost all (n = 27) mentioned that there was no lactation room in their work place and 6/28 (21.4%) of the employed mothers complained about the lack of cooperation of their employers regarding breastfeeding issues (providing flexible work hours). One-fifth of the participants, 55 (22%), faced breastfeeding problems such as nipple problems, and mastitis.

Of the 250 participants, 103 (41.2%) were rural residents, 193 (77.2%) were housewives and 171 (68.4%) had received less than secondary level education. Twenty–three (9.2%) of the mothers had medical disorders (diabetes in pregnancy (n = 2), hypertension in pregnancy including pre-eclampsia (n = 5) and other (n = 16). Less than half 114 (45.6%) of the children were females. Over three-quarters of the children, 207 (82.8%) were delivered vaginally and the remainder 43 (17.2%) by caesarean section. Ninety four percent of infants born vaginally initiated breastfeeding within the first hour of delivery compared to 77% of infants born by caesarean section (p = 0.024).

One-hundred and forty six (58.4%) of the mothers had received breastfeeding education provided by healthcare personnel during pregnancy and/or after the delivery.

About one-third, (88/250) 35.2%, of the children were hospitalized at least once in the last 6 months and spent 24 h or more at the hospital. The most common reasons for hospitalization were respiratory tract infections, gastroenteritis, and malaria. Ninety three percent of infants hospitalized had initiated breastfeeding within the first hour of delivery, compared to 84% who weren’t hospitalized (p = 0.052).

The child age, number of children less than five years, residence, mode of delivery, having received breastfeeding education, and paternal education level and occupation were found to be associated with initiation of breastfeeding in bivariate analysis only (Table 1).

In multivariable logistic regression analysis (Table 2), factors associated with the delay of breastfeeding initiation were male baby (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR] 3.90, 95% CI 1.33, 11.47), and maternal medical disorders (AOR 5.07, 95% CI 1.22, 21.16).

Discussion

The main finding of the current study was the rate of early initiation of breastfeeding (87.2%) within one hour of delivery. This rate was higher compared with the national rate (68.7%) in Sudan [19], Eastern Sudan (45.8–76.6%) [28, 31]. This rate (87.2%) is recognized by the WHO as “good” (between 50 and 89%) [17], but is low compared with 92.8% in Khartoum [4] and 90.6% in Kassala, in eastern Sudan [26]. Variations in breastfeeding rates even within the same country have been reported before in Ethiopia [32], where the highest rate was reported in Addis Ababa, (71.5%), and the lowest, (41.7%). in the Somali regional state. Low rates of early initiation of breastfeeding have been reported in other African countries, 34.7–78.3% in Nigeria [20, 21] and 51.8% in Uganda [22].

The current study showed that male infants were 3.9 times more likely to experience delayed breastfeeding initiation. This is in line with a previous study in Uganda [33]. The data regarding any relationship between infant gender and early initiation of breastfeeding are contradictory, previous studies in Turkey and India report that boys were fed earlier than girls [34, 35]. This could be explained by the difference in cultures, for example, in Sudan, it was observed after delivery of a male baby, the family members would give him more care in comparison to a female baby by handling the male baby first and then pass him to the mother for breastfeeding and this may cause delaying of initiation of breastfeeding among male babies. Moreover, male infants are at higher risk of preterm birth and morbidity, respectively [36, 37] and these factors are associated with delayed initiation of breastfeeding [38,39,40]. Although, the gestational age at birth was not mentioned, in one hospital in Sudan, high rates of preterm births were reported in 2010 and about one fifth of the total preterm births identified as medically indicated (iatrogenic) [41]. This could be explained by maternal medical disorders such as preeclampsia and premature infants requiring hospitalization, both circumstances which may lead to delayed initiation of breastfeeding.

The study found that mothers with medical disorders and their infants were more likely to experience delayed initiation of breastfeeding. Inconsistent with the current results, delayed initiation of breastfeeding was observed among mothers with medical disorders such as diabetes and hypertension [18, 42]. In an African context, among maternal medical disorders, maternal human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was found as a key barrier to early initiation of breastfeeding [43,44,45]. In Mauritius, despite the fact that 60.6% of mothers initiate breastfeeding, low rate of exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months were documented (17.9%) [46]. Several studies identify the positive influence of breastfeeding education for successful breastfeeding [47,48,49].

In spite of a high rate (17.2%) of caesarean delivery in this study, an association between caesarean delivery and early initiation of breastfeeding was not identified. This may be because the sample size was not powered to show a difference. Previous studies have shown that caesarean delivery was a key barrier for early initiation of breastfeeding in different settings [18, 21, 22, 33, 43, 50,51,52]. When compared to planned caesarean delivery, emergency caesarean delivery was found to be associated with delayed initiation of breastfeeding [53]. Further categorizations of caesarean delivery (planned/ emergency) are vital to be taken into consideration in future research [53].

This study show no association between the delayed initiation of breastfeeding and child hospitalization. This might be explained by the poor outcomes for the hospitalised children (i.e. the deaths) which the current study failed to trace. A larger sample may have shown evidence for such an association. For future research in this area larger sample size, more detail about the main reasons for hospitalization and inclusion of both mothers in the community in addition to those in hospital would be of value.

Although we have found that 59% of the mothers received breastfeeding education during the pregnancy course and/or after the delivery in logistic regression breastfeeding education was not found to be associated with breastfeeding initiation. Previous studies have shown that mothers who have received breastfeeding education were more likely to have initiate early breastfeeding [54, 55]. This could be explained by the fact that, even among the mothers who had received information about breastfeeding by healthcare personnel, more than half of them learned about breastfeeding from family members as well. Perhaps the influence of the family member on the mothers was more powerful than healthcare personnel. For example, in Myanmar, traditional beliefs that exclusive breastfeeding is not sufficient for babies and that solid foods and water were necessary are identified as barriers to the initiation of breastfeeding [56]. Moreover, in Sudan, even among healthcare workers, capacity-building regarding breastfeeding practices need to be improved [57]. To ensure the reliability of breastfeeding information, healthcare workers may require education about the provision of breastfeeding education. Involving family members in discussion about breastfeeding in a respectful and inclusive manner may help correct inaccurate information and help to share accurate information in a culturally appropriate manner.

In the current study, there was no association between maternal age, parental educational level or occupation and the initiation of breastfeeding. Previous studies have shown that parental education [54, 55, 58,59,60], occupation [59] and maternal age [58] were associated with initiation of breastfeeding. The variations of the associated factors among studies could be due to the influence of such factors on the family socioeconomic status. For example, paternal occupation could influence early initiation of breastfeeding through improving family income as high socioeconomic status was found to be associated with early initiation of breastfeeding [35, 61,62,63,64].

Although the sample size of the employed mothers among the study participants was small in comparison to studies in Ghana and Uganda [22, 65], this study highlighted two main issues, the low employment rate among the study participants and the lack of support for breastfeeding mothers who are employed. For example, some mothers faced breastfeeding problems related to work, these could be explained by several factors including poorly paid work, limited breastfeeding support in the workplace, excessive travel distance requiring long journeys between home and work and limited access to maternity leave. Further research with a larger sample size of the mothers of infants and young children would allow further exploration of the challenges experienced by women who wish to breastfeed and participate in the paid workforce.

Limitations

Study limitations included recall bias as mothers of children aged up to two years were asked for early infant feeding detail. Not tracing infant maturity status (term or preterm), gestational age, birthweight, reasons for and outcomes of infant hospitalization limited study analysis and outcomes - particularly as a recent systematic review and meta-analysis documented poor infant survival associated with delayed breastfeeding initiation [66].

Conclusion

The study concluded that the prevalence of early initiation of breastfeeding was 87.2% among mothers with children of two years or less in Kassala, Eastern Sudan. However, an association with delayed initiation of breastfeeding was found amongst mothers who had medical disorders and those who had a male infant. Wherever possible, early initiation of breastfeeding should be promoted for all infants’ regardless of gender.

Abbreviations

- AORs:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratios

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Nutrition's lifelong impact | Nutrition | UNICEF Available at https://www.unicef.org/nutrition/index_lifelong-impact.html. Acessed 4 June 2018.

Mahgoub HM, Adam I. Morbidity and mortality of severe malnutrition among Sudanese children in new Halfa hospital, eastern Sudan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106:66–8.

Kanan SOH, Swar MO. Prevalence and outcome of severe malnutrition in children less than five-year-old in Omdurman Paediatric hospital. Sudan Sudan J Paediatr. 2016;16:23–30.

Onsa ZO, Ahmed NMK. Impact of exclusive breast feeding on the growth of Sudanese children (0-24 months). Pak J Nutr. 2014;13:99–106.

Eljack IA, Rahman A, Niel AH. Child health indicators in Shareq Elneel locality, Khartoum state, Sudan: a cross-sectional study. Int J Child Health Nutr. 2015;4:67–77.

Ibrahim AMM, Alshiek MAH, Ngoma MS, Adam D. Breastfeeding among infants and its association with the nutritional status of children under five years in Khartoum. Sudan International Journal of Healthcare Sciences. 2015;3:177–84.

Executive summary: sample spatial surveying method (S3M) survey in Sudan. Khartoum; 2013. Available at http://www.coverage-monitoring.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/S3M-fact-sheet_Nov2014.pdf. Acessed 4 June 2018.

Kaur A, Singh K, Pannu MS, Singh P, Sehgal N, Kaur R. The effect of exclusive breastfeeding on hospital stay and morbidity due to various diseases in infants under 6 months of age: a prospective observational study. Int J Pediatr. 2016;2016:7647054

Gebremedhin D, Berhe H, Gebrekirstos K. Risk factors for neonatal sepsis in public hospitals of Mekelle City, North Ethiopia, 2015: unmatched case control study. PLoS One. 2016:11(5):e0154798.

Hanieh S, Ha TT, Simpson JA, Thuy TT, Khuong NC, Thoang DD, et al. Exclusive breast feeding in early infancy reduces the risk of inpatient admission for diarrhea and suspected pneumonia in rural Vietnam: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1166

Ajetunmobi OM, Whyte B, Chalmers J, Tappin DM, Wolfson L, Fleming M, et al. Breastfeeding is associated with reduced childhood hospitalization: evidence from a Scottish Birth Cohort (1997–2009). J Pediatr. 2015;166:620–625.e4.

Patel DV, Bansal SC, Nimbalkar AS, Phatak AG, Nimbalkar SM, Desai RG. Breastfeeding practices, demographic variables, and their association with morbidities in children. Adv Prev Med. 2015;892825

Monge RB. Upper airway infections related to the use of the feeding bottle in feeding the young infant. Curr Nurs Costa Rica. 2017;32:90–103.

Biks GA, Berhane Y, Worku A, Gete YK. Exclusive breast feeding is the strongest predictor of infant survival in Northwest Ethiopia: a longitudinal study. J Health Popul Nutr. 2015;34:9.

Awasthi A, Awasthi S. Promoting exclusive breastfeeding in India to reduce neonatal mortality. Clin Epidemiol Global Health. 2016;4:151–2.

World Health Organization. Early initiation of breastfeeding to promote exclusive breastfeeding. 2018. Available at http://www.who.int/elena/titles/early_breastfeeding/en/. Acessed 4 June 2018. Acessed 4 June 2018.

World Health Organization. Infant and young child feeding a tool for assessing national practices, policies and programmes. Geneva; 2003.Available at http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/inf_assess_nnpp_eng.pdf. Acessed 4 June 2018. Acessed 4 June 2018.

Takahashi K, Ganchimeg T, Ota E, Vogel JP. Prevalence of early initiation of breastfeeding and determinants of delayed initiation of breastfeeding: secondary analysis of the WHO global survey. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44868.

Sudan: Multiple indicator cluster survey 2014 - key findings.Available https://reliefweb.int/report/sudan/sudan-multiple-indicator-cluster-survey-2014-key-findings. Acessed 4 June 2018.

Mbada CE, Olowokere AE, Faronbi JO, Faremi FA, Oginni MO. Oyinlola- FC, et al. breastfeeding profile and practice of Nigerian mothers: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Res Notes. 2014;3:969–76.

Berde AS, Yalcin SS. Determinants of early initiation of breastfeeding in Nigeria: a population- based study using the 2013 demograhic and health survey data. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2016;16:32.

Mukunya D, Tumwine JK, Nankabirwa V, Ndeezi G, Tumuhamye J, Tongun JB, et al. Factors associated with delayed initiation of breastfeeding: a survey in northern Uganda. Glob Health Action. 2017;10:1410975.

Suparmi S, Saptarini I. Early initiation of breast feeding but not bottle feeding increase exclusive breastfeeding practice among less than six months infant in Indonesia. Health Sci J Indonesia. 2016;7:44–8.

Mohammed SGS. Infants feeding and weaning practices among mothers in northern Kordofan state. Sudan European Sci J. 2014;10:165–81.

ELyas TB. The knowledge, attitude and practices of mothers regarding the breast-feeding in Sinkat locality. Int J Sci Res. 2016;5:2013–6.

Eldoom EA, Mater AA, Abdelraheem EEM. Breast feeding and the weaning practices in terms of age and methodology of weaning including the age of administration of alternative feeding. European J Pharmaceut Med Res. 2016;3:38–42.

Salih MAM, Elbushra HM, Satti SAR, Ahmed MEF, Kamil IA. Attitudes and practices of breast-feeding in Sudanese urban and rural communities. Trop Geog Med. 1993;45:171–4.

Haroun HM, Mahfouz MS, Ibrahim BY. Breast feeding indicators in Sudan breast feeding indicators in Sudan: a case study of wad Medani town. Sudan J Public Health. 2008;3:81–90.

Central Bureau of Statistics (Sudan). 2018. Avialable at http://ghdx.healthdata.org/organizations/central-bureau-statistics-sudan. Acessed 4 June 2018.

The United Nations Children’s’ Fund (UNICEF). MICS 2014 Key findings. 2014 Avialable at https://wwwuniceforg/zimbabwe/MICS_Key_Findings_Report__2014_Zimbabwepdf Acessed 4 June 2018.

The United Nations Children’s’ Fund (UNICEF). MICS 2014 key findings Red Sea, Kassala, Gedarif and Blue Nile States. 2014. Avialble at https://www.unicef.org/sudan/UNICEF_Sudan_Annual_Report_2014.pdf. Acessed 4 June 2018.

Lakew Y, Tabar L, Haile D. Socio-medical determinants of timely breastfeeding initiation in Ethiopia: evidence from the 2011 nation wide demographic and health survey. Int Breastfeed J. 2015;10:24.

Bbaale E. Determinants of early initiation, exclusiveness, and duration of breastfeeding in Uganda. J Health Popul Nutr. 2014;32:249–60.

Yilmaz E, Yilmaz Z, Isik H, Gultekin IB, Timur H, Kara F, et al. Factors associated with breastfeeding initiation and exclusive breastfeeding rates in Turkish adolescent mothers. Breastfeed Med. 2016;11:315–20.

Sarkar TK, Bhattacherjee S, Mukherjee A, Saha TK, Chakraborty M, Dasgupta S. Early initiation of breast feeding in tribal children. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2016;3:3081–5.

Zeitlin J, Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, De Mouzon J, Rivera L, Ancel PY, Blondel B, et al. Fetal sex and preterm birth: are males at greater risk ? Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2762–8.

Peelen MJ, Kazemier BM, Ravelli AC, De Groot CJ, Mol BW, Hajenius MK. Impact of fetal gender on the risk of preterm birth, a national cohort study. Acta Obs Gynecol Scand. 2016;95:1034–41.

Brasil TM, Fundação E, Cruz O, Maria T, Esteves B, Daumas RP. Factors associated to breastfeeding in the first hour of life: systematic review. Rev Saúde Pública. 2014;48:697–708.

Adhikari M, Khanal V, Karkee R, Gavidia T. Factors associated with early initiation of breastfeeding among Nepalese mothers: further analysis of Nepal demographic and health survey, 2011. Int Breastfeed J. 2014;9:21.

Samad N, Haque M, Sultana S. Pattern of delivery and early initiation of breastfeeding: an urban slum based cross cut study. J Nutr Health Food Engineering. 2017;7:00244

Alhaj AM, Radi EA, Adam I. Epidemiology of preterm birth in Omdurman maternity hospital, Sudan. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23:131–4.

Oza-Frank R, Chertok I, Bartley A. Differences in breast-feeding initiation and continuation by maternal diabetes status. Public Health Nutr. 2014;18:727–35.

Kalisa R, Malande O, Nankunda J, Tumwine JK. Magnitude and factors associated with delayed initiation of breastfeeding among mothers who deliver in Mulago hospital. Uganda Afri Heal Sci. 2015;15:1130–5.

Young SL, Israel-Ballard KA, Dantzer EA, Ngonyani MM, Nyambo MT, Ash DM, et al. Infant feeding practices among HIV-positive women in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania, indicate a need for more intensive infant feeding counselling. Public Heal Nutr. 2012;13:2027–33.

Thomas E, Kuo C, Cohen S, Hoare J, Koen N, Barnett W, et al. Mental health predictors of breastfeeding initiation and continuation among HIV infected and uninfected women in a south African birth cohort study. Prev Med. 2017;102:100–11.

Motee A, Ramasawmy D, Pugo-Gunsam P, Jeewon R. An assessment of the breastfeeding practices and infant feeding pattern among mothers in Mauritius. J Nutr Metab. 2013;2013:243852

Mortazavi F, Mousavi SA, Chaman R, Wambach KA, Mortazavi S, Khosravi A. Breastfeeding practices during the first month postpartum and associated factors: impact on breastfeeding survival. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2015;17:e27814.

Froozani MD, Permehzadeh K, Motlagh ARD, Golestan B. Effect of breastfeeding education on the feeding pattern and health of infants in their first 4 months in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:381–5.

Burgio MA, Laganà AS, Sicilia A, Porta P, Porpora MG, Ban Frangež H, et al. Breastfeeding education: where are we going ? A systematic review article. Iran J Public Health. 2016;45:970–7.

Azzeh FS, Alazzeh AY, Hijazi HH, Wazzan HY, Jawharji MT, Jazar AS, et al. Factors associated with not breastfeeding and delaying the early initiation of breastfeeding in Mecca Region, Saudi Arabia. Children (Basel). 2018;5:E8.

Pandya A, Chavada M, Jain R, Verma PB. Determinants for delayed initiation of breastfeeding- a hospital based comparative study between primiparous and multiparous mothers. The Journal of Medical Research. 2015;1:49–54.

Rowe-Murray HJ, Fisher JR. Baby friendly hospital practices: cesarean section is a persistent barrier to early initiation of breastfeeding. Birth. 2002;29:124–31.

Hobbs AJ, Mannion CA, McDonald SW, Brockway M, Tough SC. The impact of caesarean section on breastfeeding initiation, duration and difficulties in the first four months postpartum. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:90.

Yurtsal ZB, Kocoglu G. The effects of antenatal parental breastfeeding education and counseling on the duration of breastfeeding, and maternal and paternal attachment. Integrative Food, Nutrition and Metabolism. 2015;2:222–30.

Martínez Galiano JM, Rodríguez M. Early initiation of breastfeeding is benefited by maternal education program. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2013;59:254–7.

Thet MM, Khaing EE, Diamond-Smith N, Sudhinaraset M, Oo S, Aung T. Barriers to exclusive breastfeeding in the Ayeyarwaddy region in Myanmar: qualitative findings from mothers, grandmothers, and husbands. Appetite. 2016;96:62–9.

Abdelrahman A, Alkhatim HS. The effect of health care providers training on exclusive breastfeeding trend at a maternity Hospital in Sudan, 2014. Annals of Clinical Laboratory Research. 2016;4:1–8.

Radwan H. Patterns and determinants of breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices of Emirati mothers in the United Arab Emirates. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:171.

Sharma A, Thakur PS, Tiwari R, Kasar PK, Sharma R, Kabirpanthi V. Factors associated with early initiation of breastfeeding among mothers of tribal area of Madhya Pradesh, India: a community based cross sectional study. Int J Community Med Public Heal. 2016;3:194–9.

Acharya P, Khanal V. The effect of mother's educational status on early initiation of breastfeeding: further analysis of three consecutive Nepal demographic and health surveys. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1069.

Tariku A, Biks GA, Wassie MM, Worku AG, Yenit MK. Only half of the mothers practiced early initiation of breastfeeding in Northwest Ethiopia, 2015. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10:501.

Hailemariam TW, Adeba E, Sufa A. Predictors of early breastfeeding initiation among mothers of children under 24 months of age in rural part of West Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1076.

Tohotoa J, Maycock B, Hauck Y, Howat P, Burns S, Binns C. Supporting mothers to breastfeed : the development and process evaluation of a father inclusive perinatal education support program in Perth. Western Australia Health Promot Int. 2011;26:351–61.

Beyene MG, Geda NR, Habtewold TD, Assen ZM. Early initiation of breastfeeding among mothers of children under the age of 24 months in southern Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J. 2017;12:1.

Dun-Dery EJ, Laar AK. Exclusive breastfeeding among city-dwelling professional working mothers in Ghana. Int Breastfeed J. 2016;11:23.

Smith ER, Hurt L, Chowdhury R, Sinha B, Fawzi W, Edmond KM, et al. Delayed breastfeeding initiation and infant survival: a systematic review and meta- analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180722.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

None received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AAH, ZT, and IA conceived and designed the study. MAA, AAA recruited the participants. AAH, ZT, MAA, AAA and IA analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All contributive authors of this original manuscript authorized the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study received ethical approval from the Research Board at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Gadarif, Sudan. The reference number is 2015/11. Written informed consent was obtained from all the enrolled patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hassan, A.A., Taha, Z., Ahmed, M.A.A. et al. Assessment of initiation of breastfeeding practice in Kassala, Eastern Sudan: a community-based study. Int Breastfeed J 13, 34 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-018-0177-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-018-0177-6