Abstract

Background

The impact of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) on the duration of breastfeeding varies between shortening and no impact. Breastfeeding seems to reduce both maternal and offspring risk for type 2 diabetes and offspring risk for overweight or obesity later in life. The aim of our study was to evaluate in primiparous women whether GDM had an influence on the duration of breastfeeding, and further, to evaluate the factors that influenced on the duration of breastfeeding.

Methods

The study cohort (N = 1089) consisted of all primiparous women with a Finnish background excluding women with pre-existing diabetes mellitus who lived in the city of Vantaa, Finland, gave birth to a singleton living child between 2009 and 2015, and with valid data on breastfeeding available. The diagnosis of GDM was based on a standard 75 g 2-h oral glucose tolerance test. Data were obtained from Finnish national registers and from the medical records of the city of Vantaa.

Results

No differences were observed in the duration of breastfeeding between women diagnosed with GDM and without GDM, 7.5 (Standard Deviation [SD] 3.7) months versus 7.9 (SD 3.5) months (p = 0.17). Women diagnosed with GDM breastfed boys for a longer duration than girls (maternal age, pre-pregnancy body mass index, marital status, educational attainment, duration of pregnancy, and smoking habits adjusted p = 0.042). Women who breastfed < 6 months were younger, were more likely smokers, had shorter education, and higher pre-pregnancy body mass index than women who breastfed over 6 months (p < 0.001 for linearity).

Conclusions

In primiparous women GDM did not influence breastfeeding duration. The positive health effects of breastfeeding should be emphasized especially in young, overweight and less educated women in order to minimize the risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes for themselves and their offspring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a common metabolic abnormality in pregnancy and globally, the prevalence of GDM has been estimated to 13% in 2019 [1]. GDM increases the risk of short- and long-term adverse health outcomes, such as an increased risk of developing metabolic and cardiovascular disorders later in life, both for the mother and offspring [2, 3]. Breastfeeding has been reported to decrease maternal risk for ovarian cancer and type 2 diabetes and offspring risk for overweight or obesity and type 2 diabetes [4,5,6,7,8,9]. Typically, in high-income countries the duration of breastfeeding is shorter than in middle- and low-income counties [7].

Previous studies have shown inconsistent findings between GDM and the duration of breastfeeding [10]. Some studies have reported that women with GDM have a shorter duration of breastfeeding than women without GDM [11,12,13,14] whereas some studies observed no difference [5, 6, 15,16,17]. Lactation difficulties among women with GDM are at least partly explained by their higher likelihood of obesity and delivery complications, including cesarean section, compared women without Gestational diabetes mellitus [18, 19]. Further, neonates of women with GDM seem to have an increased risk for both low birthweight and macrosomia as well as admissions to neonatal intensive care unit, all of which may have a detrimental influence on breastfeeding [20, 21]. Most previous data originate from study cohorts consisting of both primiparous and multiparous women. Data on the influence of GDM on the duration of breastfeeding in primiparous women is missing.

The aim of the study was to evaluate whether GDM has an influence on the duration of breastfeeding, and further, to evaluate factors that influenced duration of breastfeeding in primiparous women.

Methods

Study population

This study is an observational cohort study from the city of Vantaa, Finland. Vantaa is the fourth most populated city in Finland with 211,000 inhabitants in 2015 in the Helsinki metropolitan area. The study cohort consisted of all Finnish primiparous women without diabetes mellitus who lived in the city of Vantaa, gave birth to a singleton living child between the 1st of January 2009 and the 31st of December 2015, and whose data on breastfeeding until the offspring age of 2 years were available (N = 1089). Women were defined as Finnish if they were born in Finland and their mother tongue was Finnish or Swedish.

Maternal characteristics

Data on maternal characteristics were obtained from the Finnish Medical Birth Register maintained by the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. This register receives information on all live births and stillbirths from gestational weeks 22 or a birthweight of 500 g onwards from all Finnish maternity hospitals. From the Finnish Medical Birth Register we obtained data on the women’s age, status of cohabiting and smoking, pre-pregnancy weight and height, number of previous deliveries, number of fetuses, use of infertility treatments, duration of pregnancy at the day of delivery, delivery mode, and the presence of Gestational diabetes mellitus [22]. Pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) was calculated as pre-pregnancy weight (kg) divided by height (m) squared.

In Finland since 2008, GDM screening has been done using a 75 g 2-h oral glucose tolerance test between 24 to 28 gestation weeks in all pregnant women except those who are at low risk for GDM [23]. Nulliparous women aged less than 25 years with BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 and without a first-degree family history of diabetes are defined as low-risk women. If a woman has one or more pathological glucose value in oral glucose tolerance test with the following diagnostic thresholds it leads to GDM diagnosis: fasting plasma glucose ≥5.3 mmol/L, 1-h glucose ≥10.0 mmol/L, and 2-h glucose ≥8.6 mmol/L [23]. Gestational diabetes mellitus screening is mainly made in public antenatal clinics in primary healthcare centers and it is free-of-charge for women. The coverage of the use of the services of public antenatal clinics is as high as 99.7–99.8% [24].

Educational attainment, taxable incomes and chronic diseases

Data on educational attainment based on a national classification of years of schooling were obtained from Statistics Finland [25]. Data on maternal earned and capital taxable income were obtained from the Finnish Tax Administration. For annual income, each participant’s mean taxable income for three preceding years before delivery were used. The annual incomes were deflated for the year 2020 value by a consumer price index [25]. Data on women’s chronic diseases over 3 years before conception were obtained from the Social Insurance Institution [26]. In Finland, medication for certain chronic diseases is reimbursed at a rate of 65% or 100% based on a medical certificate prepared by the treating physician. The medical certificate contains the history and status observations of the person with a chronic disease. The expert physicians of the Finnish Social Insurance Institution review the certificate. When the reimbursement criteria for a chronic disease are fulfilled, the applicant receives a right to a reimbursable medication and at the same timepoint the entitlement is entered into a nationwide register.

Breastfeeding

Data on duration of breastfeeding were obtained from the healthcare records and based on regular follow-up visits at public child welfare clinics. Breastfeeding included both exclusive, predominant, and partial breastfeeding. The Finnish national guidelines call for predominant breastfeeding for 4 to 6 months and partial breastfeeding for 1 year [27]. The visits to the public child welfare clinics are free-of-charge. In Finland, children aged 2 years or less visit the child welfare clinics at age of 1 to 4 weeks, 4 to 6 weeks, 2 months, 3 months, 4 months, 5 months, 6 months, 8 months, 10 months, 12 months, 18 months, and 24 months [28]. The coverage of the public child welfare clinic use is as high as 99.6% [28].

Offspring birth characteristics

Data on offspring sex, birthweight, Apgar score at 1 min, and admissions to neonatal intensive care unit or need for respirator treatment before the age of 7 days were obtained from the Finnish Medical Birth Register.

Data combination

In Finland, every citizen and permanent resident has a personal identification number. With the personal identification number register data from the Finnish Medical Birth Register, Statistics Finland, the Finnish Tax Administration, the Social Insurance Institution, and the healthcare records from the child welfare clinics were combined at an individual level.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as means with SD or as counts (n) with percentages (%). Statistical comparisons between the GDM groups were made using the t-test, analysis of variance (ANOVA), chi-square test, or Fisher-Freeman test. The hypothesis of linearity across duration of breastfeeding (< 6 months, 6–11 months and ≥ 12 months) were evaluated by using the Cochran-Armitage test for trend and analysis of variance with an appropriate contrast (orthogonal polynomial). The Kaplan-Meier method was applied to estimate the cumulative probability of breastfeeding women diagnosed with and without Gestational diabetes mellitus. We used Cox proportional hazards model to calculate the adjusted hazard ratios (HR). The normality of variables was evaluated graphically and using Shapiro–Wilk W test. Stata 16.1 (StataCorp LP; College Station, Texas, USA) statistical package was used for the analysis.

Results

Characteristics of the primiparous women and their offspring by presence of GDM are shown in the Table 1. Women diagnosed with GDM were older (30.1 [SD 4.8] years versus 28.7 [SD 4.8] years, p < 0.001) and had higher pre-pregnancy BMI (26.9 [SD 5.4] kg/m2 versus 23.3 [SD 3.7] kg/m2, p < 0.001) than women in pregnancies without GDM (Table 1). No differences were observed in marital status, educational attainment, annual maternal incomes or smoking habits (Table 1). Further, no differences were observed in the offspring characteristics assessed (Table 1).

Figure 1 shows the probability of any breastfeeding after adjusting for maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, marital status, educational attainment, duration of pregnancy, smoking habits, and infant’s sex in women with and without Gestational diabetes mellitus. Mean duration of breastfeeding was 7.5 (SD 3.7) months in women diagnosed with GDM and 7.9 (SD 3.5) months in women without GDM (p = 0.17). Of the women diagnosed with GDM, five (3%) did not initiate breastfeeding at all and the corresponding number was nine (1%) among the women without Gestational diabetes mellitus (p = 0.037).

Probability of breastfeeding in primiparous women diagnosed with and without gestational diabetes mellitus. Hazard ratio is adjusted for maternal age, pre-pregnancy body mass index, marital status, educational attainment, duration of pregnancy, smoking habits, and infant’s sex. GDM = gestational diabetes mellitus; HR = hazard ratio

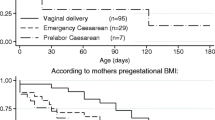

Women diagnosed with GDM breastfed boys for a longer time than girls (maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, marital status, educational attainment, duration of pregnancy, and smoking habits adjusted p = 0.042) (Fig. 2).

Impact of offspring sex and gestational diabetes mellitus and their interaction on the duration of breastfeeding in women diagnosed with and without gestational diabetes mellitus, adjusted for maternal age, pre-pregnancy body mass index, marital status, educational attainment, duration of pregnancy, and smoking habits. GDM = gestational diabetes mellitus

Table 2 shows the characteristics of primiparous women and their offspring by the duration of breastfeeding. Women who breastfed < 6 months were younger, more likely smokers, had lower educational attainment, and had higher pre-pregnancy BMI than women who breastfed 6–11 months or ≥ 12 months (for all p < 0.001 for linearity) (Table 2). Further, women who breastfed < 6 months were more often unmarried and had lower annual income than women who breastfed 6–11 months or ≥ 12 months (for all p = 0.002 for linearity) (Table 2). No differences were observed in the characteristics of the offspring (Table 2).

Discussion

We observed no differences in the duration of breastfeeding between primiparous women diagnosed with GDM and those without Gestational diabetes mellitus. The women breastfed their offspring for an average of almost 8 months. Women with GDM breastfed boys for a longer time than girls. Women who breastfed their offspring for a long time were typically older, slimmer, non-smokers, and better educated than women who breastfed for a short time.

Our study findings endorse previous study findings that GDM does not influence duration of breastfeeding [5, 6, 16]. In this cohort including Finnish primiparous women, the average duration of breastfeeding was almost 8 months. Further, 70% of the women breastfed their offspring for at least 6 months and almost 20% at least 12 months. Previous studies have reported that in high income countries around 45% of women breastfed their offspring for at least 6 months and around 25% for at least 12 months [7]. The variations are considerable, for example in Norway around 70% of women breastfed their offspring for at least 6 months and around 35% at least 12 months, and in Denmark around 15% at least 6 months and 3% at least 12 months, respectively [7]. At least in part, the large differences in breastfeeding duration are explained by the fact that the duration of maternity leave varies greatly from country to country. In Finland, mothers have an entitlement for 105 working days maternity leave paid by the Finnish Social Insurance Institution [29]. In addition, after the maternity leave the Finnish Social Insurance Institution pays parental allowance, either to mother or father, for 158 working days [30]. All in all, this means that a child is typically the first 9 months at homecare. After the parental allowance, if the child is taken care of at home, the parents are entitled to a child home allowance paid by the Finnish Social Insurance Institution until the child is 3 years old [31]. Further during the past 10 years in Finland, the counselling for breastfeeding has been intensified both in maternity hospitals and maternity clinics [32].

Interestingly, we observed that women diagnosed with GDM breastfed their boys longer than girls. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have report findings on the presence of Gestational diabetes mellitus, offspring’s sex and duration of breastfeeding. Overall, previous study findings on the association between offspring’s sex and duration of breastfeeding have been inconsistent [21, 33,34,35,36]. In the Newcastle Thousand Families study no sex difference in the duration of breastfeeding was reported [36]. Similarly, in a Chinese study no sex differences in relation to duration of breastfeeding were found [21]. Contrary in an Indian study, girls were breastfed for shorter periods than boys [35]. In a US study no gender differences were observed in the duration of breastfeeding except in Hispanic mothers who breastfed their boys for shorter time than girls [34]. Breastfeeding related issues are obviously highly related to cultural factors [17, 34]. However, the underlying factors explaining our study observations that women diagnosed with GDM breastfed their boys longer than girls remains unclear.

According to our observations, primiparous women who breastfed for a long time were characterized by higher age than women who breastfed a short time. This observation is line with previous study including both primiparous and multiparous women [37]. Further, endorsing previous studies we found that women with higher degree of adiposity, breastfed their offspring for shorter duration than slimmer women [12, 37,38,39,40]. There are some evidence that overweight and obese women may have increased progesterone concentrations and/or decreased prolactin response to infant suckling leading breastfeeding problems [18]. Also, large breasts may make it more challenging for the infant to achieve a correct latch [18]. In line with previous studies, we found that non-smokers, higher educated, and married women had a longer duration of breastfeeding [20, 37, 39]. Some studies have shown that delivery complications, such as Caesarean section, or serious health problems of the newborn lead to lactation difficulties [19, 20, 38]. We did not observe such an influence. A long duration of breastfeeding seems to associate with beneficial health outcomes for the mother and offspring [4,5,6,7,8,9].

Our study has several strengths. Data on deliveries, maternal characteristics, and infant’s birth characteristics were based on the Finnish Medical Birth Register, which has been found to be of good quality [41]. Data on educational attainment, taxable incomes, and chronic diseases were based on reliable register data. Breastfeeding data were documented in the medical records by healthcare professionals. We studied only primiparous women to avoid biases of previous pregnancies and breastfeeding.

Study limitations

We had only data on any breastfeeding, not separately on exclusively, predominant and partial breastfeeding. We were missing on data on women’s dietary and physical activity habits as well as gestational weight gain, which all may influence the duration of breastfeeding. In our study cohort, the number of women who did not initiate breastfeeding at all was low; this study finding would be needed to confirm in a larger study population. Further, all women were Finnish, thus, the generalizability of our study observations is limited.

Conclusions

In a high-income country like Finland with a long maternity leave and a well-functioning public free-of-charge antenatal and children welfare clinic organization, GDM had no influence on the duration of breastfeeding. The positive health effects of breastfeeding should be emphasized especially in young, overweight and less educated women in order to minimize the risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes for themselves and their offspring.

Availability of data and materials

Data cannot be shared for both legal and ethical reasons. Data from the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL), Statistics Finland, the Finnish Social Insurance Institution, and the city of Vantaa can only be used for the purpose stated in the license granted, scientific research on society by the license applicant, and can therefore not be shared with third parties.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CI:

-

confidential intervals

- GDM:

-

gestational diabetes mellitus

- HR:

-

hazard rate

- SD:

-

standard deviation

References

International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 9th ed. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation; 2019. Accessed 20 Nov 2020.

Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:1773–9.

Metzger BE, Lowe LP, Dyer AR, Trimble ER, Chaovarindr U, Coustan DR, et al. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1991–2002.

Tanase-Nakao K, Arata N, Kawasaki M, Yasuhi I, Sone H, Mori R, Ota E. Potential protective effect of lactation against incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2017;33:e2875. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.2875.

Aris IM, Soh SE, Tint MT, Saw SM, Rajadurai VS, Godfrey KM, et al. Associations of infant milk feed type on early postnatal growth of offspring exposed and unexposed to gestational diabetes in utero. Eur J Nutr. 2017;56:55–64.

Bider-Canfield Z, Martinez MP, Wang X, Yu W, Bautista MP, Brookey J, et al. Maternal obesity, gestational diabetes, breastfeeding and childhood overweight at age 2 years. Pediatr Obes. 2017;12:171–8.

Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJD, Franca GVA, Horton S, Krasevec J, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;378:475–90.

Horta BL, Loret de Mola C, Victora CG. Long-term consequences of breastfeeding on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104:30–7.

Aune D, Norat T, Romundstad P, Vatten LJ. Breastfeeding and maternal risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;24:107–15.

Nguyen PTH, Pham NM, Chu KT, Duong DV, Do DV. Gestational diabetes and breastfeeding outcomes: a systematic review. Asia Pacific J Public Health. 2019;31:183–98.

Nguyen PTH, Binns CW, Nguyen CL, Ha AVV, Chu TK, Duong DV, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus reduces breastfeeding duration: a prospective cohort study. Breastfeed Med. 2019;14:39–45.

Baerug A, Sletner L, Laake P, Fretheim A, Loland BF, Waage CW, et al. Recent gestational diabetes was associated with mothers stopping predominant breastfeeding earlier in a multi-ethnic population. Acta Paediatr. 2018;107:1028–35.

Weisband YL, Rausch J, Kachoria R, Gunderson EP, Oza-Frank R. Hospital supplementation differentially impacts the association between breastfeeding intention and duration among women with and without gestational diabetes mellitus history. Breastfeed Med. 2017;12:338–44.

Oza-Frank R, Chertok I, Bartley A. Differences in breast-feeding initiation and continuation by maternal diabetes status. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18:727–35.

Wallenborg JT, Perera RA, Masho SW. Breastfeeding after gestational diabetes: does perceived benefits mediate the relationship? J Pregnancy. 2017;9581796. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9581796.

Oza-Frank R, Moreland JJ, McNamara K, Geraghty SR, Keim SA. Early lactation and infant feeding practices differ by maternal gestational diabetes history. J Hum Lact. 2016;32:658–65.

Veena SR, Krishnaveni GV, Wills AK, Hill JC, Karat SC, Fall CHD. Glucose tolerance and insulin resistance in Indian children: relationship to infant feeding pattern. Diabetologia. 2011;54:2533–7.

Trout KK, Averbuch T, Barowski M. Promoting breastfeeding among obese women and women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Curr Diab Rep. 2011;11:7–12.

Cakmak H, Kuguoglu S. Comparison of the breastfeeding patterns of mothers who delivered their babies per vagina and via cesarean section: an observational study using the LATCH breastfeeding charting system. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017;44:1128–37.

Reinheimer SM, Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Drehmer M. Factors associated with breastfeeding among women with gestational diabetes. J Hum Lact. 2020;36:126–35.

Tang L, Lee AH, Binns CW. Factors associated with breastfeeding duration: a prospective cohort study in Sichuan province, China. World J Pediatr. 2015;11:232–8.

Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. Perinatal statistics – parturients, delivers and newborns 2019. https://www.thl.fi/en/statistics/parturients. Accessed 20 Nov 2020.

Gestational Diabetes, Current Care Guidelines 2013. Working group set up by the Finnish medical society Duodecim, the medical Advosiry Board of the Finnish Diabetes Association and the Finnish gynecological association. Available in internet www.kaypahoito.fi. Accessed 20 Nov 2020.

Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. Äitiysneuvola. https://thl.fi/fi/web/lapset-nuoret-ja-perheet/peruspalvelut/aitiys_ja_lastenneuvola/aitiysneuvola). Accessed 20 Nov 2020.

Statistics Finland. National classification of education 2016. https://www.stat.fi/en/luokitukset/koulutus/koulutus_1_20160101. Accessed 20 Nov 2020.

Statistics Finland. Consumer price index. https://www.stat.fi/til/khi/index_en.html. Accessed 20 Nov 2020.

Kela. Applying for entitlement to reimbursement of medicine expenses. https://kela.fi/web/en/medicine-expenses-special-reimbursement. Accessed 20 Nov 2020.

Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. Imetyssuositukset. https://thl.fi/fi/web/lastenneuvolakasikirja/imetys/imetyssuositukset. Accessed 20 Nov 2020.

Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. Lastenneuvola. https://thl.fi/fi/web/lapset-nuoret-ja-perheet/peruspalvelut/aitiys_ja_lastenneuvola/lastenneuvola. Accessed 20 Nov 2020.

Kela. Maternity allowance. https://www.kela.fi/web/en/maternity-allowance. Accessed 20 Nov 2020.

Kela. Parental allowance. https://www.kela.fi/web/en/parental-allowance. Accessed 20 Nov 2020.

Kela. Child home care allowance. https://www.kela.fi/web/en/child-home-care-allowance. Accessed 20 Nov 2020.

Kansallinen imetyksen edistämisen asiantuntijaryhmä (2009). Imetyksen edistäminen Suomessa. Toimintaohjelma 2009-2012. Raportti/Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos (THL):32/2009 [Breastfeeding Promotion in Finland. Action Programme 2009–2012]. National Institute for Health and Welfare THL, Report 32/2009]. http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe201205085091. Accessed 20 Nov 2020.

Shafer EF, Hawkins SS. The impact of sex of child on breastfeeding in the United States. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21:2114–21.

Fledderjohann J, Agrawal S, Vellakal S, Basu S, Campbell O, Doyle P, et al. Do girls have a nutritional disadvantage compared with boys? Statistical models of breastfeeding and food consumption inequalities among Indian siblings. Plos One. 2014;9:e107172. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0107172.

Pearce MS, Relton CL, Parker L, Unwin NC. Sex differences in the association between infant feeding and blood cholesterol in later life: the Newcastle thousand families cohort study at age 49-51 years. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24:375–80.

Martin H, Thevenet-Morrison K, Dozier A. Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain and breastfeeding outcomes: a cross-sectional analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:471. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03156-8.

Fenger-Gron J, Fenger-Gron M, Blunck CH, Schonemann-Rigel H, Wielandt HB. Low breastfeeding rates and body mass index in Danish children of women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Int Breastfeed J. 2015;10:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-015-0051-8.

Bartok C. J, Schaefer EW, Beiler JS, Paul IM. Role of body mass index and gestational weight gain in breastfeeding outcomes. Breastfeed Med. 2012; 7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2011.0127.

Wojcicki JM. Maternal prepregnancy body mass index and initiation and duration of breastfeeding: a review of the literature. J Women's Health. 2011;20:341–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2010.2248.

Gissler M, Teperi J, Hemminki E, Merilainen J. Data quality after restructuring a national medical registry. Scand J Soc Med. 1995;23:75–80.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Tove Victoria Eriksson for her invaluable assistance in data processing.

Funding

The Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa, Finland, awarded a research grant for this study. The funding source had no role for preparations of this article nor in study design, data collection, analyses or writing the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MKL contributed to study design, data collection and researched data, wrote the manuscript, contributed to the interpretation of the results and to the discussion, reviewed the paper critically and approved the final version of the manuscript. HK contributed to study design, data collection and researched data, performed the statistical analyses, contributed to the interpretation of the results and to the discussion, reviewed the paper critically and approved the final version of the manuscript. MG contributed to the interpretation of the results and to the discussion, reviewed the paper critically and approved the final version of the manuscript. PP contributed to the interpretation of the results and to the discussion, reviewed the paper critically and approved the final version of the manuscript. JGE contributed to study design, data collection and researched data, contributed to the interpretation of the results and to the discussion, reviewed the paper critically and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study has been approved by the ethics committee of the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa, Finland (356/13/03/03/2015, 2 November 2015), and the health authority of the city of Vantaa, Finland. Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL), Statistics Finland, the Finnish Tax Administration, and the Social Insurance Institution has given permission to use register data in the study. Informed consents were not required because the study is an observational register-based cohort study and no study participants were contacted.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Laine, M.K., Kautiainen, H., Gissler, M. et al. Impact of gestational diabetes mellitus on the duration of breastfeeding in primiparous women: an observational cohort study. Int Breastfeed J 16, 19 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-021-00369-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-021-00369-1