Abstract

Background

This international online survey investigated the experience and impact of emotional blunting in the acute and remission phases of depression from the perspective of patients and healthcare providers (HCPs). This paper presents data on the history and severity of psychological trauma and its potential impact on emotional blunting in major depressive disorder (MDD); differences between patient and HCP perceptions are explored.

Methods

Patient respondents (n = 752) were adults with a diagnosis of depression who were currently taking antidepressant therapy and reported emotional blunting during the past 6 weeks. HCPs provided details on two eligible patients: one in the acute phase of depression and one in remission from depression (n = 766). Trauma was assessed using questions based on the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; emotional blunting was assessed using the Oxford Depression Questionnaire (ODQ). Multivariate regression analyses were applied to examine the relationship between trauma and ODQ score.

Results

A history of any childhood or recent traumatic event was reported by 97% of patients in the self-assessed cohort and for 83% of those in the HCP-assessed cohort (difference, p < 0.01). Patients were more likely than HCPs to feel that this trauma had contributed to their/the patient’s depression (58% vs 43%, respectively; p < 0.01) and that the depression was more severe because of trauma (70% vs 61%, respectively; p < 0.01). Emotional blunting was significantly worse in patients who reported severe trauma than in those who had not experienced severe trauma (mean total ODQ score, 90.1 vs 83.9, respectively; p < 0.01). In multivariate regression analyses, experiencing both severe childhood and recent trauma had a statistically significant impact on ODQ total score (p = 0.001).

Conclusions

A high proportion of patients with depression and emotional blunting self-reported exposure to childhood and/or recent traumatic events, and emotional blunting was more severe in patients who reported having experienced severe trauma. However, history of psychological trauma in patients with MDD appeared to be under-recognized by HCPs. Improved recognition of patients who have experienced psychological trauma and are experiencing emotional blunting may permit more targeted therapeutic interventions, potentially resulting in improved treatment outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is well documented that exposure to psychological trauma can have negative effects on mental health. A history of trauma (e.g., during childhood) has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of developing mental health disorders, such as depression [1,2,3,4], and patients with depression are significantly more likely to report exposure to traumatic life events than individuals without depression [5,6,7]. In the International Study to Predict Optimized Treatment for Depression (iSPOT-D), patients with depression were found to be significantly more likely than healthy control participants to report early-life stress—particularly interpersonal violation (emotional, sexual, and physical abuse) [7]. In all, 62.5% of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) reported more than two traumatic events, compared with 28.4% of control individuals [7].

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a major psychological impact worldwide. Studies have shown increased prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression in the general population of many countries since the start of the pandemic, both in individuals who have contracted the virus and those who have not [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. The psychological impact of the pandemic appears to be even greater in certain groups, such as patients with pre-existing mental health conditions [18, 19].

A history of psychological trauma has been shown to be associated with more severe disease in patients with depression [20,21,22], including poorer responses to antidepressant treatment [7, 22, 23] and a greater risk of suicide [24, 25]. In iSPOT-D, patients with MDD who had been exposed to abuse at 4–7 years of age were significantly less likely to achieve response or remission following treatment with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (escitalopram or sertraline) or serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (venlafaxine extended release) than those who had not experienced abuse at this age [odds ratio 1.57 for response (p = 0.034) and 1.61 for remission (p = 0.032)] [7].

Emotional blunting is a common symptom in patients with MDD and is increasingly being recognized as an important factor preventing full functional recovery [26,27,28,29]. However, data on the association of psychological trauma with emotional blunting in patients with depression are lacking. Anhedonia—the inability to experience pleasure—is one aspect of emotional blunting, and is one of the core diagnostic criteria for a major depressive episode [30]. Patients with MDD and a history of psychological trauma have been shown to experience greater levels of anhedonia than those without such a history [31]. Emotional blunting or numbing is also common in prolonged grief disorder [32] and is a core defining feature of post-traumatic stress disorder, presenting as diminished interest in activities, detachment from others, and the inability to experience positive emotions [33, 34]. In patients with post-traumatic stress disorder, the presence of emotional numbing has been shown to be associated with increased symptom severity, functional impairment, and suicide ideation [34,35,36].

This online survey was undertaken to explore the experience of emotional blunting in patients with MDD in the acute and remission phases of depression from the perspective of both patients and healthcare providers (HCPs). Findings concerning the clinical characteristics of emotional blunting in patients with depression and the impact of emotional blunting on functioning and overall quality of life from the patient perspective have been reported in the first two papers in this series [37, 38]. The current paper presents data on the prevalence and severity of psychological trauma and its potential impact on the severity of emotional blunting in patients with depression who were experiencing emotional blunting; differences between patient and HCP perceptions are also explored.

Methods

Study design and participants

This was a quantitative, cross-sectional, observational study conducted by BPR Pharma (London, UK) in Brazil, Canada, and Spain between April 15 and May 18, 2021. The study design is described in detail in the first paper in this series [37]. The study was approved by an institutional review board (Veritas IRB, Montreal, QC, Canada), was conducted in accordance with the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association (EphMRA) code of conduct, and adhered to General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and all local market laws regarding data protection. Participants were recruited through an existing online panel of consumers and healthcare providers. Participants had previously consented to participate in research; however, informed consent was also obtained specifically for this study.

Patient respondents were aged 18–70 years, had been diagnosed with depression by a physician, were currently taking a prescribed antidepressant, and reported experiencing emotional blunting in the last 6 weeks. Emotional blunting was confirmed by a validated screening question [39]: ‘Emotional effects of depression and treatment vary, but may include, for example, feeling emotionally “numbed” or “blunted” in some way; lacking positive emotions or negative emotions; feeling detached from the world around you; or “just not caring” about things that you used to care about. Have you experienced such emotional effects during the last 6 weeks?’ Only patients in the acute or remission phases of depression were eligible for study participation. The acute phase was defined as: ‘A time when your symptoms are at their worst or most severe and for which you use antidepressant treatment.’ The remission phase was defined as: ‘A time when your symptoms have improved significantly and you are already feeling better, but you may or may not still experience some minor symptoms. You are still taking antidepressant medication.’ Quotas were imposed for patient age (≥ 50 years, 50%) and sex (female, 60%).

HCP respondents were psychiatrists (n = 226) or primary care physicians (n = 157) spending ≥ 75% of their time in direct patient care and prescribing antidepressants to ≥ 75% of their patients with depression. For psychiatrists, quotas were imposed on hospital and office settings (each 50%). Patients assessed by HCPs were required to be aged 18–75 years, diagnosed with depression, and receiving antidepressant medication. HCPs completed the survey for the last two eligible patients with whom they had a consultation: one in the acute phase of depression (defined as ‘A patient experiencing acute symptoms of depression that require antidepressant treatment’), and one in the remission phase of depression (defined as ‘The patient feels better and experiences a significant reduction in symptoms compared to other phases. Some residual symptoms may persist, but are significantly fewer in number and severity compared to other phases. The patient is still on antidepressant medication’).

Patients and HCPs were unmatched (i.e., patients who participated in this survey were not the same patients as those described by the HCPs).

Outcome measures

For both surveys, trauma questions were based on the validated Childhood Trauma Questionnaire [40]. Questions concerned: (i) childhood trauma (i.e., trauma occurring before the age of 17 years); and (ii) recent trauma (i.e., occurring within the last 3 years). Questions captured whether patients had experienced any of a range of different traumatic events during these two time periods, including: the death of a very close friend or family member; any upheaval between parents or with a spouse (e.g., their parents’ or their own divorce or separation); a traumatic sexual experience (e.g., rape or sexual assault); being a victim of violence (other than sexual); being extremely ill or injured; major change at work (recent trauma only); and any other major upheaval that may have significantly shaped their life or personality. Patients reported their personal experiences of childhood and recent psychological trauma; HCPs reported whether their respective patients had experienced these same traumas in childhood or recently. Patients also rated the severity of the traumatic event experienced on a 7-point numerical rating scale, where a score of 6 or 7 was considered indicative of severe trauma. HCPs were not asked to rate trauma severity.

Patients assessed the severity of their emotional blunting using the Oxford Depression Questionnaire (ODQ). This validated instrument for assessing emotional blunting in patients with depression comprises 26 questions covering five domains: general reduction in emotions, reduction in positive emotions, emotional detachment from others, not caring, and antidepressant as cause [39, 41]. The ODQ total score ranges from 26 to 130, with higher scores indicating more severe emotional blunting. Patients also completed the Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST), a brief self-report instrument that is used to assess problems with daily functioning [42]. For the purposes of this survey, the period of recall for the FAST was ‘during this acute or remission phase of depression’. The FAST total score ranges from 0 to 72, with higher scores indicating greater functional impairment.

Statistical analysis

The analysis population comprised all respondents who met the inclusion criteria and completed the online survey. Respondents who failed to complete the survey or who completed the survey much faster than average were excluded from the final sample. Any respondent who responded ‘don’t know’ to more than one item for any FAST domain was excluded from the analysis of that domain. For patients who responded ‘don’t know’ to just one item in any FAST domain, the mean score for the other items answered in that domain was used to impute the missing value (as per the scale guidance). Respondents with a missing score for any domain were removed from the calculation of FAST total score (a missing score would result from them having responded ‘don’t know’ to more than one item in that domain).

Data were analyzed separately for patients and HCPs. Data are presented descriptively using means and standard deviations for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Comparisons were performed for continuous measures using t tests and for proportions using Z tests. For the patient-reported cohort, ODQ scores and FAST total score were analyzed according to the type of severe trauma reported (severe childhood, severe recent, or any severe).

Multivariate regression analysis was applied to assess whether a history of psychological trauma had an independent and significant impact on emotional blunting (i.e., ODQ total score) after controlling for other patient characteristics (demographics and symptoms of depression). Regression was assessed on: (a) demographic variables (age group, sex, education, country); (b) symptoms of depression (anxiety, physical symptoms, cognitive symptoms, mood symptoms); and (c) trauma type (severe childhood trauma only, severe recent trauma only, both severe childhood and recent trauma, neither). Variable sets (a), (b), and (c) were entered hierarchically as blocks. Block (a) was force-entered, with variables in block (b) and (c) entered only if they had a statistically significant effect (determined using backward and forward selection). Statistical significance determined by either method was considered valid.

Data were analyzed by The Stats People (Sevenoaks, UK) using MERLIN tabulation software and Microsoft Excel; significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Experience of trauma

Data were available for 752 self-assessed and 766 HCP-assessed patients (Table 1). Sociodemographic characteristics were generally similar in the two patient cohorts. However, the proportion of patients with a history of past or present drug or alcohol abuse was more than twice as high in the self-assessed cohort than in the HCP-assessed cohort, both overall and for each phase of depression (acute and remission). The proportion of patients with a history of any trauma was significantly higher in the self-assessed cohort than in the HCP-assessed cohort (97% vs 83%, respectively; p < 0.01).

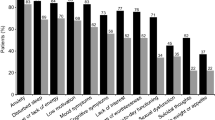

A total of 658 patients reported severe trauma (88% of the overall patient-reported cohort; 68% severe childhood trauma and 75% severe recent trauma). In all, 419 patients (56%) reported both severe childhood and recent trauma (Table 1). As shown in Fig. 1, the proportion of patients reporting severe trauma was significantly higher among those in the acute versus the remission phase of depression across all trauma categories (all p < 0.01). The proportion of patients reporting severe trauma was higher in Brazil than in Canada and Spain across all categories (Fig. 2; most differences between Brazil and other countries, p ≤ 0.05).

The most common childhood traumatic experience reported by patients was the death of a very close friend or family member (reported by 61% of patients in the acute phase of depression and 56% of those in remission) (Fig. 3). Patients in the acute phase of depression were significantly more likely than those in the remission phase to report any upheaval between their parents (42% vs 33%; p < 0.05) and childhood sexual abuse (38% vs 28%; p < 0.01). Overall, 33% of patients reported having been a childhood victim of violence (35% in the acute phase of depression and 32% in remission). HCPs reported lower rates of all types of traumatic events during childhood than patients (Fig. 3).

The most common recent traumatic experiences reported by patients were the death of a very close friend or family member (65%) and a major change at work (55%) (Fig. 3). According to HCPs, however, only 34% of patients had recently experienced bereavement and 41% had experienced a major change at work. Patients in the acute phase of depression were significantly more likely to report the following recent traumatic events compared with patients in remission: extreme illness or injury (41% vs 32%, respectively; p < 0.01), any upheaval with spouse (32% vs 25%; p < 0.05), traumatic sexual experience (12% vs 7%; p < 0.01), and other recent traumatic experiences (62% vs 48%; p < 0.01).

Irrespective of the phase of depression, patients were more likely than HCPs to feel that their experience of trauma had contributed to their/the patient’s depression (58% vs 43%, respectively; p < 0.01) and that the depression was more severe because of their/the patient’s experience of trauma (70% vs 61%; p < 0.01) (Fig. 4).

ODQ and FAST scores

Mean total ODQ scores were significantly higher (i.e., indicative of more severe emotional blunting) in patients with a history of severe trauma than in those without severe trauma in each trauma category (all p < 0.01) (Table 2). For ODQ domain scores, the greatest differences between patients with and without severe trauma were seen for the ‘reduction in positive emotions’ (difference for each severe trauma category, p < 0.01), ‘general reduction in emotions’ (difference, p < 0.05 for severe childhood trauma and p < 0.01 for severe recent and any severe trauma), and ‘not caring’ domains (difference, p < 0.05 for any severe trauma and p < 0.01 for severe childhood or severe recent trauma). No significant differences were seen between groups for the ‘antidepressant as cause’ domain in any trauma category. Mean total FAST scores were significantly higher (i.e., worse) in patients with a history of severe childhood or recent trauma than in those without (both p < 0.01) (Table 2).

Relationship between trauma and emotional blunting

In the multivariate regression analysis, symptoms of depression (specifically mood symptoms, followed by physical symptoms) were found to account for the greatest part of the accumulative variance in ODQ total score (Fig. 5). Experiencing both severe childhood and recent trauma was found to statistically significantly impact the ODQ total score (p = 0.001), although it accounted for only 1.4% of the total accumulative variance in ODQ total score (R2, 10.4%). Experiencing either severe childhood or recent trauma alone had no significant impact on ODQ total score.

Stepwise multivariate regression analysis to predict the extent to which the ODQ score is predicted by severe trauma.aODQ percentage is accumulative, reflecting history of trauma and control variables, banxiety, mood symptoms (sadness, lack of enjoyment, hopelessness), physical symptoms (decrease in weight or appetite, disturbed sleep, fatigue, sexual dysfunction), and cognitive symptoms (trouble concentrating, difficulties making plans, forgetfulness) were assessed by the survey questionnaire, cage group, sex, education, and country. ODQ, Oxford Depression Questionnaire

Discussion

Our findings show that experience of psychological trauma is prevalent in patients with depression; almost all patients (97%) reported experiencing a traumatic event at some point during their life, and 88% reported severe trauma. The prevalence of self-reported trauma in this study is higher than that reported in other populations with depression [7, 21, 43]. An analysis of general population surveys from 24 countries across six continents, with 68,894 adult respondents, found that more than 70% of respondents had experienced at least one traumatic event [44]. Five types of trauma (witnessing death or serious injury, the unexpected death of a loved one, being mugged, being in a life-threatening automobile accident, and experiencing a life-threatening illness or injury) accounted for more than half of all exposures. In the current study, the proportion of patients in Brazil reporting severe trauma was higher across all categories than in Canada and Spain; geographic differences in the prevalence of trauma are not unexpected [44], and may be due to factors such as differences in willingness to disclose sensitive information and differing levels of violence in society.

In the current study, more than two-thirds of patients reported experiencing severe childhood trauma and three-quarters reported severe recent trauma. Patients who had experienced severe trauma reported more severe emotional blunting (i.e., higher ODQ total score) and greater functional impairment (i.e., higher FAST total score) than those who had not experienced severe trauma. In the multivariate regression analysis, experiencing both severe childhood and recent trauma was found to have a significant and independent impact on severity of emotional blunting (i.e., higher ODQ total score).

It is therefore noteworthy that our findings suggest that HCPs may underestimate the proportion of patients with depression who have experienced psychological trauma, especially during childhood. Furthermore, patients were significantly more likely than HCPs to think that psychological trauma was a reason for their depression and that their depression was more severe because of it. Other studies have shown clinically relevant differences between patient and HCP perceptions of depression [45,46,47]. Nevertheless, the possibility that patients may have overestimated the potential impact of their experience of psychological trauma on their depression cannot be excluded.

An improved understanding of patients’ lived experiences of depression is important in order to ensure that treatment is appropriate to their needs. Patients with a history of trauma appear to have a suboptimal response to treatment with some antidepressants [7, 23]. Improved recognition of patients with trauma and emotional blunting may permit more targeted therapeutic interventions, resulting in improved treatment outcomes. For example, the multimodal antidepressant vortioxetine has demonstrated significant efficacy in relieving depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with MDD reporting childhood or recent trauma [43]. Furthermore, if patients experience blunted emotions with their current treatment for depression then alternative antidepressants should be explored. In one recent study, patients with MDD who experienced emotional blunting and an inadequate response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor monotherapy reported significant improvements in emotional blunting, depressive symptoms, cognitive performance, motivation and energy, and overall functioning after 8 weeks of treatment with vortioxetine 10–20 mg/day [48].

Methodologic considerations

The main strengths of this study are its large sample size, with participants recruited from three countries, and assessment from the perspective of both patients and HCPs. Potential limitations include selection bias (i.e., by design all patients were experiencing emotional blunting and patients may have been more likely to consent to study participation because of their experience of trauma) and the possibility of recall bias with retrospective reporting of childhood trauma, particularly in individuals with mental health disorders [49, 50]; for example, depressed mood may increase the likelihood of recall of negative experiences. It should also be noted that data are lacking concerning duration and frequency of exposure to the traumatic experience(s) and history of any other psychiatric disorders, particularly post-traumatic stress disorder, as these factors may also potentially have contributed to the prevalence and severity of emotional blunting in the two patient cohorts. Finally, comparisons between the self-assessed and HCP-assessed cohorts should be interpreted with caution, as patient- and HCP-provided responses were unmatched (i.e., the patients who completed the survey themselves were not the same patients as those reported on by HCPs).

Conclusion

In summary, our study shows that a very high percentage of patients with depression and emotional blunting self-report exposure to childhood and/or recent psychological trauma, and that emotional blunting is more severe in patients with depression who have experienced severe psychological trauma than in those who have not. While patients often reported that trauma is a reason for their depression and that their depression is more severe because of this experience, exposure to potential psychological trauma and its possible impact in patients with depression appeared to be under-recognized by HCPs. Differences between patient and HCP perspectives concerning the experience of emotional blunting in MDD will be further explored in the final paper in this series [51]. Improved recognition of patients who have experienced psychological trauma and are experiencing emotional blunting may permit more targeted therapeutic interventions, potentially resulting in improved treatment outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available given the informed consent provided by survey participants. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the authors.

References

Dube SR, Anda RF, Whitfield CL, Brown DW, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Giles WH. Long-term consequences of childhood sexual abuse by gender of victim. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(5):430–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.015.

Laugharne J, Lillee A, Janca A. Role of psychological trauma in the cause and treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23(1):25–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283345dc5.

Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Hinesley J, et al. Association of childhood trauma exposure with adult psychiatric disorders and functional outcomes. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(7):e184493. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.449.

Kuzminskaite E, Penninx BWJH, van Harmelen AL, Elzinga BM, Hovens JGFM, Vinkers CH. Childhood trauma in adult depressive and anxiety disorders: an integrated review on psychological and biological mechanisms in the NESDA cohort. J Affect Disord. 2021;283:179–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.054.

Kendler KS, Kessler RC, Walters EE, MacLean C, Neale MC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ. Stressful life events, genetic liability, and onset of an episode of major depression in women. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(6):833–42. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.152.6.833.

Hovens JG, Wiersma JE, Giltay EJ, van Oppen P, Spinhoven P, Penninx BW, Zitman FG. Childhood life events and childhood trauma in adult patients with depressive, anxiety and comorbid disorders vs controls. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;122(1):66–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01491.x.

Williams LM, Debattista C, Duchemin AM, Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB. Childhood trauma predicts antidepressant response in adults with major depression: data from the randomized International Study to Predict Optimized Treatment for Depression. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6(5):e799. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2016.61.

Bäuerle A, Teufel M, Musche V, et al. Increased generalized anxiety, depression and distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study in Germany. J Public Health (Oxf). 2020;42(4):672–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdaa106.

Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health substance use and suicidal ideation during the COVID 19 pandemic—United States June 24-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1049–57. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1.

Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, Galea S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2019686. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686.

Huang Y, Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954.

Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob Health. 2020;16(1):57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w.

Dutheil F, Mondillon L, Navel V. PTSD as the second tsunami of the SARS-Cov-2 pandemic. Psychol Med. 2021;51(10):1773–4. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720001336.

Fiorenzato E, Zabberoni S, Costa A, Cona G. Cognitive and mental health changes and their vulnerability factors related to COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0246204. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246204.

Frontera JA, Yang D, Lewis A, et al. A prospective study of long-term outcomes among hospitalized COVID-19 patients with and without neurological complications. J Neurol Sci. 2021;426:117486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2021.117486.

Niedzwiedz CL, Green MJ, Benzeval M, et al. Mental health and health behaviours before and during the initial phase of the COVID-19 lockdown: longitudinal analyses of the UK Household Longitudinal Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2021;75(3):224–31. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-215060.

Vanderlind WM, Rabinovitz BB, Miao IY, et al. A systematic review of neuropsychological and psychiatric sequelae of COVID-19: implications for treatment. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2021;34(4):420–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000713.

Hao F, Tan W, Jiang L, et al. Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown? A case-control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:100–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.069.

Liu CH, Stevens C, Conrad RC, Hahm HC. Evidence for elevated psychiatric distress, poor sleep, and quality of life concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic among U.S. young adults with suspected and reported psychiatric diagnoses. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292:113–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113345.

Wiersma JE, Hovens JG, van Oppen P, Giltay EJ, van Schaik DJ, Beekman AT, Penninx BW. The importance of childhood trauma and childhood life events for chronicity of depression in adults. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(7):983–9. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.08m04521.

Hovens JG, Giltay EJ, Wiersma JE, Spinhoven P, Penninx BW, Zitman FG. Impact of childhood life events and trauma on the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;126(3):198–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01828.x.

Nanni V, Uher R, Danese A. Childhood maltreatment predicts unfavorable course of illness and treatment outcome in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(2):141–51. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020335.

Nemeroff CB, Heim CM, Thase ME, et al. Differential responses to psychotherapy versus pharmacotherapy in patients with chronic forms of major depression and childhood trauma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(24):14293–6. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2336126100.

Fuller-Thomson E, Baird SL, Dhrodia R, Brennenstuhl S. The association between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and suicide attempts in a population-based study. Child Care Health Dev. 2016;42(5):725–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12351.

Goldberg X, Serra-Blasco M, Vicent-Gil M, et al. Childhood maltreatment and risk for suicide attempts in major depression: a sex-specific approach. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2019;10(1):1603557. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1603557.

Price J, Cole V, Goodwin GM. Emotional side-effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: qualitative study. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(3):211–7. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.108.051110.

Read J, Cartwright C, Gibson K. Adverse emotional and interpersonal effects reported by 1829 New Zealanders while taking antidepressants. Psychiatry Res. 2014;216(1):67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.01.042.

Goodwin GM, Price J, De Bodinat C, Laredo J. Emotional blunting with antidepressant treatments: a survey among depressed patients. J Affect Disord. 2017;221:31–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.048.

Read J, Williams J. Adverse effects of antidepressants reported by a large international cohort: emotional blunting, suicidality, and withdrawal effects. Curr Drug Saf. 2018;13(3):176–86. https://doi.org/10.2174/1574886313666180605095130.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Fan J, Liu W, Xia J, et al. Childhood trauma is associated with elevated anhedonia and altered core reward circuitry in major depression patients and controls. Hum Brain Mapp. 2021;42(2):286–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.25222.

Prigerson HG, Boelen PA, Xu J, Smith KV, Maciejewski PK. Validation of the new DSM-5-TR criteria for prolonged grief disorder and the PG-13-Revised (PG-13-R) scale. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):96–106. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20823.

Litz BT, Gray MJ. Emotional numbing in posttraumatic stress disorder: current and future research directions. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2002;36(2):198–204. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01002.x.

Malta LS, Wyka KE, Giosan C, Jayasinghe N, Difede J. Numbing symptoms as predictors of unremitting posttraumatic stress disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23(2):223–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.07.004.

Kerig PK, Bennett DC, Chaplo SD, Modrowski CA, McGee AB. Numbing of positive, negative, and general emotions: associations with trauma exposure, posttraumatic stress, and depressive symptoms among justice-involved youth. J Trauma Stress. 2016;29(2):111–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22087.

Li G, Wang L, Cao C, et al. An item-based analysis of PTSD emotional numbing symptoms in disaster-exposed children and adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2020;48(10):1303–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-020-00677-w.

Christensen MC, Ren H, Fagiolini A. Emotional blunting in patients with depression. Part I: clinical characteristics. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2022;21(1):10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-022-00387-1.

Christensen MC, Ren H, Fagiolini A. Emotional blunting in patients with depression. Part II: relationship with functioning, well-being and quality of life. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2022; in press.

Price J, Cole V, Doll H, Goodwin GM. The Oxford Questionnaire on the Emotional Side-effects of Antidepressants (OQuESA): development, validity, reliability and sensitivity to change. J Affect Disord. 2012;140(1):66–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.01.030.

Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, et al. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(8):1132–6. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132.

Christensen MC, Fagiolini A, Florea I, Loft H, Cuomo A, Goodwin GM. Validation of the Oxford Depression Questionnaire: sensitivity to change, minimal clinically important difference, and response threshold for the assessment of emotional blunting. J Affect Disord. 2021;294:924–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.07.099.

Rosa AR, Sánchez-Moreno J, Martínez-Aran A, et al. Validity and reliability of the Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST) in bipolar disorder. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2007;3:5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-0179-3-5.

Christensen MC, Florea I, Loft H, McIntyre RS. Efficacy of vortioxetine in patients with major depressive disorder reporting childhood or recent trauma. J Affect Disord. 2020;263:258–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.074.

Benjet C, Bromet E, Karam EG, et al. The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychol Med. 2016;46(2):327–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715001981.

Baune BT, Christensen MC. Differences in perceptions of major depressive disorder symptoms and treatment priorities between patients and health care providers across the acute, post-acute, and remission phases of depression. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:335. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00335.

Christensen MC, Wong CMJ, Baune BT. Symptoms of major depressive disorder and their impact on psychosocial functioning in the different phases of the disease: do the perspectives of patients and healthcare providers differ? Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:280. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00280.

Kan K, Jörg F, Buskens E, Schoevers RA, Alma MA. Patients’ and clinicians’ perspectives on relevant treatment outcomes in depression: qualitative study. BJPsych Open. 2020;6(3):e44. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.27.

Fagiolini A, Florea I, Loft H, Christensen MC. Effectiveness of vortioxetine on emotional blunting in patients with major depressive disorder with inadequate response to SSRI/SNRI treatment. J Affect Disord. 2021;283:472–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.106.

Colman I, Kingsbury M, Garad Y, et al. Consistency in adult reporting of adverse childhood experiences. Psychol Med. 2016;46(3):543–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715002032.

Reuben A, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, et al. Lest we forget: comparing retrospective and prospective assessments of adverse childhood experiences in the prediction of adult health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016;57(10):1103–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12621.

Christensen MC, Ren H, Fagiolini A. Emotional blunting in patients with depression. Part IV: differences between patient and physician perceptions. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2022; in press.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the patients and healthcare providers who participated in this study. The internet survey and corresponding analyses were provided by Matt Brooks and Bridget Pumfrey of BPR Pharma Ltd, funded by H. Lundbeck A/S. Statistical analyses were performed by The Stats People, funded by H. Lundbeck A/S. Medical writing assistance and editorial support were provided by Jennifer Coward and Julie Ponting of Piper Medical Communications, funded by H. Lundbeck A/S.

Funding

This study was funded by H. Lundbeck A/S.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the concept and design of the study, and interpretation of the data. All authors contributed to all stages of manuscript development. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants (patients and healthcare providers) had previously accepted the online panel partners’ privacy policies and terms and conditions, including consent to participate in future research. Informed consent was also obtained from all participants specifically for this study prior to screening. The study and all associated materials were approved by an institutional review board prior to initiation (Veritas IRB, Montreal, QC, Canada). The study was conducted in accordance with the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association (EphMRA) code of conduct, which ensures respondent confidentiality, and adhered to General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) and all local market laws regarding data protection.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

MCC is an employee of H. Lundbeck A/S. HR was an employee of H. Lundbeck A/S at the time this study was conducted. AF has been a consultant and/or speaker and/or has received research grants from Allergan, Angelini, Apsen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo Brasil Farmacêutica, DOC Generici, FB-Health, Italfarmaco, Janssen, Lundbeck, Mylan, Otsuka, Pfizer, Recordati, Sanofi Aventis, Sunovion, and Vifor Pharma.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Christensen, M.C., Ren, H. & Fagiolini, A. Emotional blunting in patients with depression. Part III: relationship with psychological trauma. Ann Gen Psychiatry 21, 21 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-022-00395-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-022-00395-1