Abstract

Background

This study aimed to investigate the association between posttraumatic stress disorder and the risk of developing erectile dysfunction.

Methods

In this population-based retrospective cohort study, we used Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database to analyze patients who were newly diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) between 2000 and 2013, with a 1:3 ratio by age and index year matched with patients in a non-PTSD comparison group, for the risk of erectile dysfunction.

Results

In total, 5 out of 1079 patients in the PTSD group developed erectile dysfunction, and 3 out of 3237 patients in the non-PTSD group (47.58 vs. 9.03 per 100,000 per person-year) developed erectile dysfunction. The Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that the PTSD cohort had a significantly higher risk of erectile dysfunction (log-rank, p < 0.001). The Cox regression analysis revealed that the study subjects were more likely to develop an injury (hazard ratio: 12.898, 95% confidence intervals = 2.453–67.811, p = 0.003) after adjusting for age, monthly income, urbanization level, geographic region, and comorbidities. Psychotropic medications used by the patients with PTSD were not associated with the risk of erectile dysfunction.

Conclusions

Patients who suffered from PTSD had a higher risk of developing erectile dysfunction.

Highlights

-

Utilizing a nationwide, population-based database, the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database in 2000–2015 in Taiwan, which comprised 2 million people, we conducted a study to clarify the association between posttraumatic stress disorder and erectile dysfunction.

-

Posttraumatic stress disorder was associated with the risk of erectile dysfunction.

-

Psychotropic medications in the subjects with PTSD were not associated with the risk of erectile dysfunction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a devastating and debilitating mental illness that occurs after exposure to traumatic events, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) involves a cluster of symptoms, such as intrusion, hyperarousal, avoiding stimuli associated with traumatic events, and negative alterations in cognition and mood [1, 2]. PTSD can also lead to negative impacts on quality of life and functional impairment in various domains, including sexual dysfunction [3,4,5,6]. However, erectile dysfunction (ED) in PTSD is usually underreported in clinical practice and has received little attention in PTSD research, especially in Asian countries.

Few studies have investigated the correlation or rates of ED across PTSD populations [7, 8], and almost no literature has addressed the longitudinal effects of sexual dysfunction. Although it is noteworthy that the percentage of sexual dysfunction is astonishingly high in PTSD patients [9, 10], some inconsistent results have been reported regarding relationship between PTSD and sexual dysfunction [11]. For example, previous studies showed that veterans with sexual dysfunction have significantly more severe PTSD symptoms than those without sexual dysfunction [12]; however, one cross-sectional study in Turkey reported no association between lifetime PTSD and ED [13]. A systemic review reported that the prevalence of sexual dysfunction among veterans with PTSD could be between 8 and 89% in different study sample sizes [11]. Hence, there are still many investigations that need to be explored, including different prevalences of PTSD among all countries and inadequate treatment [14, 15], as well as PTSD and sexual dysfunction. Moreover, it has been suggested that comorbid mental and physical illnesses should be considered an alternative explanation of the co-occurrence of sexual dysfunction and PTSD [9, 16], such as anxiety and depression [17]. Co-occurring physical illnesses may also have bidirectional relationships, as sexual dysfunction is linked to nearly every organ system, including cardiovascular illness (e.g., stroke, coronary artery disease, and hypertension), diabetes mellitus, asthma and alcohol-related diseases [18]. Furthermore, prescription medications could represent the underlying mechanism that explains the co-occurrence of ED and PTSD, such as serotonin reuptake inhibitors and benzodiazepines [19, 20].

There are only a few studies and systematic reviews examining the impact of PTSD on ED in the general population of Asian countries. Since the relationship between PTSD and ED remains unclear, we conducted a nationwide population-based cohort study to investigate the association between PTSD and the risk of ED among Taiwanese people. We hypothesized that there is an increased risk of ED after a PTSD diagnosis, and we used the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) to examine whether there is an association between PTSD and ED.

Methods

Data sources

The Taiwan National Health Insurance (NHI) program was launched in 1995 to provide a centralized health insurance system for its citizens, and as of 2014 approximately 93% of the nation’s medical care institutions were contracted, with an enrollment rate exceeding 99% of Taiwan’s population [21]. The NHIRD is derived from the Taiwan NHI program, and all claimed data are released by the Bureau of National Health Insurance for research purposes. The NHIRD uses the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes to record diagnoses [22]. The quality and validity of the NHIRD is adequate, and its data have been used in many published studies [23,24,25]. In the present study, we used the datasets from the Registry for the 1-million Longitudinal Health Insurance Database (LHID) which included comprehensive outpatient and inpatient information, such as demographic data, dates of clinical visits, diagnostic codes, and details of prescriptions, with regard to nearly 1 million beneficiaries in Taiwan over a 13-year period from the LHID (2000–2013).

Study design and sampled participants

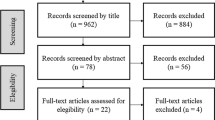

This study was a retrospective study with a matched-cohort design. Patients with PTSD were selected from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2013, according to ICD-9-CM code 309.81. In addition, each enrolled adult male PTSD patient was required to have made at least three outpatient visits within the one-year study period according to the ICD-9-CM codes. Patients diagnosed with ED before 2000 or before the first visit for PTSD were excluded. In addition, all patients aged < 20 years were excluded. A total of 4310 enrolled patients with 1079 subjects with PTSD and 3237 in the age- and index-year-matched control group without PTSD were included in this study, during a 13-year follow-up to December 31, 2013 (Fig. 1). The required sample size for data analysis is 388 in PTSD group (actual sample size is 1079), and 1164 in non-PTSD group (actual sample size is 3237). Besides, the expected Cohen’s d effect size in this study equals to 0.9015. As a sensitivity analysis, by excluding the ED diagnoses within the first and first 5 years after the enrollment of PTSD and non-PTSD groups, we could reduce the protopathic bias or carry-over effects. Therefore, the outcome measures could be more valid.

Covariates

The covariates included age group (20–39 years, ≥ 40 years), geographic area of residence (north, center, south, west, and east of Taiwan), urbanization level of residence (levels 1–4), levels of hospitals as medical centers, regional hospitals, and local hospitals, and monthly income (in New Taiwan Dollars [NT$]: < 18,000, 18,000–34,999, ≥ 35,000). The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was used to define comorbidities [26, 27]. The population and various indicators defined the urbanization levels. Urbanization level 1 was defined as a population of > 1,250,000; level 2 was defined as a population between 500,000 and 1,249,999; and levels 3 and 4 were defined as a population between 149,999 and 499,999 and < 149,999, respectively [28].

Comorbidity

Baseline comorbidities (in ICD-9-CM codes) included dementia, schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorders, depression, stroke, coronary artery diseases (CAD), hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), asthma, and alcohol-related illnesses, with the reference from one previous study [29]. All the ICD-9-CM codes of comorbidities were listed in Table S1 (Additional file 1). Data on the usage of psychotropic medications, including antidepressants, antipsychotics, and hypnosedatives, were collected. The defined daily dose (DDD) data were obtained from the WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology (https://www.whocc.no/), and the duration of the use of drugs was calculated by dividing the cumulative doses by the DDD of drugs.

Main outcomes

All of the study participants were followed from the index date until the onset of erectile dysfunction (ED), withdrawal from the NHI program, or the end of 2013. ED was divided into two subgroups: psychogenic ED and organic ED, and the ICD-9-CM codes of ED were listed in Table S1 (Additional file 1).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software V.22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). The χ2 test and t-test were used to evaluate the distributions of the categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Fisher’s exact test was used for the categorical variables to statistically examine the differences between the two cohorts. The Cox regression model was used to determine the risk of psychiatric disorders, and the results are presented as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The difference in the cumulative incidence of psychiatric disorders between the study and control groups was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method with the log-rank test. A two-tailed p value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Sample characteristics

Table 1 shows that the PTSD group had more anxiety disorders, bipolar disorders, and depression and less CAD and DM than the non-PTSD group. The PTSD group also tended to have lower CCI scores, live in the northern and outlying islands of Taiwan, reside more in urbanization level 2 regions, and receive medical help from medical centers. There were no differences in the distribution of age and insurance premiums between these two groups.

Kaplan–Meier model for the cumulative risk of erectile dysfunction

At the end of the follow-up, five patients in the PTSD group (5 in 1079, 47.58 per 105 person-years) developed ED, and three patients in the non-PTSD group (3 in 3237, 9.03 per 105 person-years) developed ED. The Kaplan–Meier analysis for the cumulative incidence of erectile dysfunction in the study and control groups is shown in Fig. 2 (log-rank test, p < 0.001).

Hazard ratio analysis of ED in patients with PTSD

In the Cox regression analysis model, the crude HR of the PTSD group was 14.766 (95% CI 3.426–63.635, p < 0.001), and the adjusted HR of the PTSD group in the development of ED was 12.898 (95% CI 2.453–6–7.811, p = 0.003), in comparison to the non-PTSD group, after adjustment for age, insurance premiums, comorbidities, antidepressants, sedatives/hypnotics, urban levels and regions in Taiwan, and the levels of hospitals the patients used for medical care. Patients with comorbidities, such as such anxiety disorders (adjusted HR: 1.864, p = 0.025), bipolar disorders (adjusted HR: 1.998, p = 0.014), and depression (adjusted HR: 2.970, p = 0.001), were associated with the risk of ED (Table 2). The use of antidepressants, antipsychotics, and sedatives/hypnotics by patients were not associated with the development of ED.

Subgroup analysis of ED in the patients with PTSD

Table 3 depicts that PTSD was associated with an increased risk of ED in the PTSD cohort in comparison to the non-PTSD cohort in the subgroup analysis. Compared with patients without anxiety disorders, PTSD had a significantly adjusted HR (7.804, p = 0.014). Patients with anxiety disorders and PTSD had a more significant adjusted HR (18.191, p < 0.001) than patients with anxiety but not PTSD, with a similar phenomenon in bipolar disorders (8.406 vs. 13.978) and depression (7.975 vs. 19.911).

Types of ED after PTSD

Table 4 reveals that in the PTSD cohort, PTSD was associated with an increased overall risk of developing ED with an adjusted HR of 12.898 (95% CI 2.453–67.811, p = 0.003) and an increased risk of developing psychogenic ED with an adjusted HR of 27.044 (95% CI 2.731–267.795, p < 0.001), but not for developing organic ED.

Discussion

Our results supported the study hypothesis that patients with PTSD would have an increased risk of developing erectile dysfunction. The log-rank of the Cox regression model was significant (p = 0.003). The adjusted HR was 12.898 (95% CI 2.453–67.811, p = 0.003). When compared with previous research on the association between PTSD and the risk of ED [8, 10, 16], this study focused on longitudinal changes in the general population of an Asian country. Previous nationwide cohort studies in the Taiwan NHIRD have reported that PTSD was associated with obstructive sleep apnea [30], bronchial asthma [31], hypertension, DM, dyslipidemia [32], osteoporosis [33], Parkinson’s disease [34], dementia [35], and epilepsy [36]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study on the topic of the association between PTSD and the risk of ED in a nationwide, population-based cohort study in an Asian country.

For the lifetime prevalence of PTSD, one study showed ranges from 1.3 to 12.2%, and the one-year prevalence was 0.2 to 3.8% [37]. Another previous study using the NHIRD found that the one-year incidence of PTSD was 1.1% [23]. In our study, the total incidence within the 13-year follow-up period was approximately 0.31% (3050 in 989,753), and when we excluded the 1971 cases of PTSD that did not meet the enrollment criteria of this study, the incidence was 0.11% (1079/989,753); both of these rates were lower than the findings in the 2014 study by Lin et al. This is likely due to the fact that men are hesitant to discuss their sexual lives with their doctors and do not seek medical help for ED and PTSD, or because doctors do not properly document the diagnoses in medical records using ICD-9 codes. Moreover, the discrepancy between the incidences in these two studies might well be related to the strict criteria we employed in the enrollment of PTSD; that is, each enrolled adult male PTSD patient was required to have made at least three outpatient visits within the 1-year study period according to ICD-9-CM codes 309.81.

In consideration of other psychiatric illnesses, such as anxiety, depression and bipolar disorder, our results showed that these comorbidities also contributed to the risk of developing erectile dysfunction; this is compatible with previous findings with bidirectional mechanisms [16, 38]. The percentage of ED in PTSD group due to comorbid depression, anxiety and bipolar disorders is higher, and the result is also consistent with PTSD had psychogenic ED predominantly, not organic ED [39,40,41]. Endothelial dysfunction, sexual hormones and inflammation in the neural circuitry, susceptible to PTSD, may play crucial roles on the pathogenic effects of ED. Furthermore, in clinical practice guidelines, the most common psychotropic medications used by patients with PTSD include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), other antidepressants, sedative-hypnotics, and antipsychotics [42]. Among these medications, antipsychotics and lithium are often prescribed for the treatment of PTSD patients and are commonly reported to have adverse effects on sexual function [43, 44]. Previous studies have also reported that antidepressants, antipsychotics and benzodiazepines were associated with ED [45, 46]. However, in this study, the usage of psychotropic medications for PTSD was not associated with an increased risk of ED after adjusting for age, comorbidity, and other covariates. Some probable reasons might be considered, such as poor drug adherence and stigmatization. This implies that more studies are needed to clarify the impact of these medications on the risk of ED in patients with PTSD.

There is an enormous amount of evidence indicating a multifactorial etiology for erectile dysfunction, either organic or non-organic, and a complex interaction exists with psychological, interpersonal, social, cultural, physiological, and gender-influenced processes [47, 48]. Several possible reasons could explain the underlying mechanism. PTSD itself can lead to a higher prevalence of erectile dysfunction, and a higher prevalence of comorbidities exists among patients with PTSD [7]. In addition, patients with PTSD are treated with psychotropic drugs, which can cause side effects that could influence their sexual function [49, 50].

Despite recent studies that highlighted the relationship between ED and PTSD, finding an absolute causation and mechanism of treatment for a patient with ED suffering from PTSD is still challenging. The main limitation of this study is that the number of ED patients in this sample was small, which might be related to underestimation of self-report, stigmatization, and a lower percentage of doctor visits due to cultural factors. Patients with ED may choose not to talk to doctors due to embarrassment, discouragement, or disbelief of the treatment possibilities.

Conclusions

The patients with PTSD had a higher risk of developing erectile dysfunction than those without PTSD, as determined after adjustment for demographic data and medical and psychiatric comorbidities. PTSD should be considered a predisposing factor in clinical practice while treating patients with erectile dysfunction. As the future direction for research, further study is therefore necessary to clarify the definite pathophysiology between PTSD and erectile dysfunction and to investigate whether prompt interventions for PTSD may reduce ED risk.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to confidentiality of data collected from the centralized Health and Welfare Data Science Centers.

Abbreviations

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery diseases

- CCI:

-

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- DDD:

-

Defined daily dose

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- ED:

-

Erectile dysfunction

- HWDC:

-

Health and Welfare Data Science Centers

- ICD-9-CM:

-

International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification

- LHID:

-

Longitudinal Health Insurance Database

- MOHW:

-

Ministry of Health and Welfare

- NHI:

-

National Health Insurance

- NHIRD:

-

National Health Insurance Research Database

- NT$:

-

New Taiwan Dollars

- PTSD:

-

Posttraumatic stress disorder

- SNRIs:

-

Serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

- SSRIs:

-

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

References

Stein DJ, Seedat S, Iversen A, Wessely S. Post-traumatic stress disorder: medicine and politics. Lancet. 2007;369(9556):139–44.

Yehuda R. Post-traumatic stress disorder. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(2):108–14.

Sayers SL, Farrow VA, Ross J, Oslin DW. Family problems among recently returned military veterans referred for a mental health evaluation. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(2):163–70.

Pietrzak RH, Goldstein MB, Malley JC, Johnson DC, Southwick SM. Subsyndromal posttraumatic stress disorder is associated with health and psychosocial difficulties in veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(8):739–44.

Danielsson FB, Schultz Larsen M, Norgaard B, Lauritsen JM. Quality of life and level of post-traumatic stress disorder among trauma patients: a comparative study between a regional and a university hospital. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2018;26(1):44.

Cook JM, Riggs DS, Thompson R, Coyne JC, Sheikh JI. Posttraumatic stress disorder and current relationship functioning among World War II ex-prisoners of war. J Fam Psychol. 2004;18(1):36–45.

Arbanas G. Does post-traumatic stress disorder carry a higher risk of sexual dysfunctions? J Sex Med. 2010;7(5):1816–21.

Badour CL, Gros DF, Szafranski DD, Acierno R. Problems in sexual functioning among male OEF/OIF veterans seeking treatment for posttraumatic stress. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;58:74–81.

Letourneau EJ, Schewe PA, Frueh BC. Preliminary evaluation of sexual problems in combat veterans with PTSD. J Trauma Stress. 1997;10(1):125–32.

Cosgrove DJ, Gordon Z, Bernie JE, Hami S, Montoya D, Stein MB, Monga M. Sexual dysfunction in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Urology. 2002;60(5):881–4.

Bentsen IL, Giraldi AG, Kristensen E, Andersen HS. Systematic review of sexual dysfunction among veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Sex Med Rev. 2015;3(2):78–87.

Nunnink SE, Goldwaser G, Afari N, Nievergelt CM, Baker DG. The role of emotional numbing in sexual functioning among veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Mil Med. 2010;175(6):424–8.

Evren C, Can S, Evren B, Saatcioglu O, Cakmak D. Lifetime posttraumatic stress disorder in Turkish alcohol-dependent inpatients: relationship with depression, anxiety and erectile dysfunction. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;60(1):77–84.

Alonso J, Liu Z, Evans-Lacko S, Sadikova E, Sampson N, Chatterji S, Abdulmalik J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Al-Hamzawi A, Andrade LH, et al. Treatment gap for anxiety disorders is global: results of the World Mental Health Surveys in 21 countries. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35(3):195–208.

Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Chatterji S, Lee S, Ormel J, Ustun TB, Wang PS. The global burden of mental disorders: an update from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2009;18(1):23–33.

Kotler M, Cohen H, Aizenberg D, Matar M, Loewenthal U, Kaplan Z, Miodownik H, Zemishlany Z. Sexual dysfunction in male posttraumatic stress disorder patients. Psychother Psychosom. 2000;69(6):309–15.

Ginzburg K, Ein-Dor T, Solomon Z. Comorbidity of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression: a 20-year longitudinal study of war veterans. J Affect Disord. 2010;123(1–3):249–57.

Clayton A, Ramamurthy S. The impact of physical illness on sexual dysfunction. Adv Psychosom Med. 2008;29:70–88.

Anticevic V, Britvic D. Sexual functioning in war veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Croat Med J. 2008;49(4):499–505.

Fossey MD, Hamner MB. Clonazepam-related sexual dysfunction in male veterans with PTSD. Anxiety. 1994;1(5):233–6.

Ho Chan WS. Taiwan’s healthcare report 2010. EPMA J. 2010;1(4):563–85.

Chinese Hospital Association, editor. ICD-9-CM English–Chinese dictionary. Taipei, Taiwan; 2000.

Lin KH, Chu PC, Kuo CY, Hwang YH, Wu SC, Guo YL. Psychiatric disorders after occupational injury among National Health Insurance enrollees in Taiwan. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219(3):645–50.

Shen CC, Tsai SJ, Perng CL, Kuo BI, Yang AC. Risk of Parkinson disease after depression: a nationwide population-based study. Neurology. 2013;81(17):1538–44.

Shih CJ, Chu H, Chao PW, Lee YJ, Kuo SC, Li SY, Tarng DC, Yang CY, Yang WC, Ou SM, et al. Long-term clinical outcome of major adverse cardiac events in survivors of infective endocarditis: a nationwide population-based study. Circulation. 2014;130(19):1684–91.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Charlson ME, Charlson RE, Peterson JC, Marinopoulos SS, Briggs WM, Hollenberg JP. The Charlson comorbidity index is adapted to predict costs of chronic disease in primary care patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(12):1234–40.

Chang CY, Chen WL, Liou YF, Ke CC, Lee HC, Huang HL, Ciou LP, Chou CC, Yang MC, Ho SY, et al. Increased risk of major depression in the three years following a femoral neck fracture—a national population-based follow-up study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e89867.

Yang YJ, Chien WC, Chung CH, Hong KT, Yu YL, Hueng DY, Chen YH, Ma HI, Chang HA, Kao YC, et al. Risk of erectile dysfunction after traumatic brain injury: a nationwide population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Am J Mens Health. 2018;12(4):913–25.

Lin CE, Chung CH, Chen LF, Chien WC, Chou PH. The impact of antidepressants on the risk of developing obstructive sleep apnea in posttraumatic stress disorder: a nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(9):1233–41.

Hung YH, Cheng CM, Lin WC, Bai YM, Su TP, Li CT, Tsai SJ, Pan TL, Chen TJ, Chen MH. Post-traumatic stress disorder and asthma risk: a nationwide longitudinal study. Psychiatry Res. 2019;276:25–30.

Lin CE, Chung CH, Chen LF, You CH, Chien WC, Chou PH. Risk of incident hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia after first posttraumatic stress disorder diagnosis: a nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2019;58:59–66.

Huang WS, Hsu JW, Huang KL, Bai YM, Su TP, Li CT, Lin WC, Chen TJ, Tsai SJ, Liou YJ, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and risk of osteoporosis: a nationwide longitudinal study. Stress Health. 2018;34(3):440–5.

Chan YE, Bai YM, Hsu JW, Huang KL, Su TP, Li CT, Lin WC, Pan TL, Chen TJ, Tsai SJ, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and risk of Parkinson disease: a nationwide longitudinal study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25(8):917–23.

Wang TY, Wei HT, Liou YJ, Su TP, Bai YM, Tsai SJ, Yang AC, Chen TJ, Tsai CF, Chen MH. Risk for developing dementia among patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: a nationwide longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2016;205:306–10.

Chen YH, Wei HT, Bai YM, Hsu JW, Huang KL, Su TP, Li CT, Lin WC, Wu YH, Pan TL, et al. Risk of epilepsy in individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder: a nationwide longitudinal study. Psychosom Med. 2017;79(6):664–9.

Karam EG, Friedman MJ, Hill ED, Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Petukhova M, Sampson L, Shahly V, Angermeyer MC, Bromet EJ, et al. Cumulative traumas and risk thresholds: 12-month PTSD in the World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(2):130–42.

Atlantis E, Sullivan T. Bidirectional association between depression and sexual dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med. 2012;9(6):1497–507.

Wang SC, Lin CC, Chen CC, Tzeng NS, Liu YP. Effects of oxytocin on fear memory and neuroinflammation in a rodent model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(12):3848.

Kaya-Sezginer E, Gur S. The inflammation network in the pathogenesis of erectile dysfunction: attractive potential therapeutic targets. Curr Pharm Des. 2020;26(32):3955–72.

Mendoza C, Barreto GE, Avila-Rodriguez M, Echeverria V. Role of neuroinflammation and sex hormones in war-related PTSD. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2016;434:266–77.

Ipser JC, Stein DJ. Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15(6):825–40.

Elnazer HY, Sampson A, Baldwin D. Lithium and sexual dysfunction: an under-researched area. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2015;30(2):66–9.

Montejo AL, Majadas S, Rico-Villademoros F, Llorca G, De La Gandara J, Franco M, Martin-Carrasco M, Aguera L, Prieto N. Spanish Working Group for the Study of Psychotropic-Related Sexual D: frequency of sexual dysfunction in patients with a psychotic disorder receiving antipsychotics. J Sex Med. 2010;7(10):3404–13.

Zainol M, Sidi H, Kumar J, Das S, Ismail SB, Hatta MH, Baharuddin N, Ravindran A. Co-morbid erectile dysfunction (ED) and antidepressant treatment in a patient—a management challenge? Curr Drug Targets. 2019;20(2):182–91.

Montejo AL, Montejo L, Navarro-Cremades F. Sexual side-effects of antidepressant and antipsychotic drugs. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2015;28(6):418–23.

Perelman MA. The sexual tipping point: a mind/body model for sexual medicine. J Sex Med. 2009;6(3):629–32.

Reed GM, Drescher J, Krueger RB, Atalla E, Cochran SD, First MB, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Arango-de Montis I, Parish SJ, Cottler S, et al. Disorders related to sexuality and gender identity in the ICD-11: revising the ICD-10 classification based on current scientific evidence, best clinical practices, and human rights considerations. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(3):205–21.

Harvey KV, Balon R. Clinical implications of antidepressant drug effects on sexual function. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1995;7(4):189–201.

Reisman Y. Sexual consequences of post-SSRI syndrome. Sex Med Rev. 2017;5(4):429–33.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate Taiwan’s Health and Welfare Data Science Center and the Ministry of Health and Welfare (HWDC, MOHW) for providing the National Health Research Database. We also thank Mr. Michael Wise who revised and proofread the language in the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Tri-Service General Hospital Research Foundation (TSGH-C108-003, TSGH-C108-151, and TSGH-E-110240), Armed Forces Taoyuan General Hospital (TYAFGH-A-110020), and the Medical Affairs Bureau, Ministry of Defense, Taiwan (MAB-107-084, MND-MAB-110-087).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SCW, NST, and YPL conceived, designed and conducted the study, performed the statistical analyses, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. WCC and CHC participated in its conception, design, assisted with the data collection and scoring of the behavioral measures, analyzed and interpreted the data, and were involved in drafting the manuscript and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. SCW wrote the first draft. NST and YPL conducted the critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The identifiable database of individuals included in the NHIRD was encrypted to protect individual privacy. In addition, all researchers followed the Computer-Processed Personal Data Protection Law and related regulations in Taiwan and signed an agreement declaring that no attempt would be made to retrieve information potentially violating the privacy of patients or health care providers. Furthermore, the data retrieval and collection could only be done in the centralized Health and Welfare Data Science Centers (HWDC). Smartphones, tablets, laptops, electronic wearable devices, or any other electronic storage devices were not allowed to be carried into the HWDC. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tri-Service General Hospital (TSGHIRB-2-106-05-029), and written informed consent was waived.

Consent for publication

All of the authors have consented to publication of this research.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

ICD-9-CM codes of comorbidities and major outcomes.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, SC., Chien, WC., Chung, CH. et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and the risk of erectile dysfunction: a nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. Ann Gen Psychiatry 20, 48 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-021-00368-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-021-00368-w