Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to assess outcome in long-term quality of life (QoL) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among adult survivors of trauma. Secondary aim was to compare levels of the outcome with injury severity and specialization level of two trauma centres.

Methods

A retrospective study included patients received by the trauma response teams at two hospitals in 2013 aged 18 or more at follow-up. We assessed QoL and PTSD with one mailed questionnaire to each patient at either 12 or 24 months of follow-up. Health status was measured by EuroQol EQ-5D and the Glasgow Outcome Scale. PTSD symptoms were classified according to the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV).

Results

A questionnaire was mailed to 774 patients at end of 2014 or early 2015, 455 were included for analysis; median age 44 (IQR 25–57; 68% male); median NISS 9 (IQR 2–17); At follow-up 24% (95% CI 20–28) reported a EQ index score value equivalent to the lowest 2.3% in the Danish population norm. Probable PTSD was present in 19% (95% CI 13–27) of patients with severe injuries (NISS> 15), and 23% (95% CI 19–28) of those with NISS < 15.

Conclusion

Severe trauma has substantial impact on QoL and PTSD assessed at 12–24 months after the trauma. The QoL was well below the Danish population norm. The presence of PTSD was independent of injury severity. Trauma Centres should consider to include this as part of the treatment principles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Injury is the leading cause of death in people aged 5–44 in high-income countries, and the leading cause of death and disability for all age groups below 60 worldwide [1]. This amounts to 10% of global deaths [2]. Furthermore, injury represents a major cost to families, the health care system and society [3].

Major improvements in the quality of trauma care have been made in recent decades, and this has reduced the number of potentially avoidable deaths [4]. Injury severity is most often classified using the Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) as a basis for the Injury Severity Score (ISS) and the New Injury Severity Score (NISS). These scores are used in the assessment of overall injury severity in patients with multiple injuries. Injury severity classification is considered to be a fundamental component of trauma outcome research and quality assessments, and thus a crucial variable in modern trauma registries. Improvements in trauma care, combined with improvements in injury prevention and prehospital care, have increased the probability of surviving a major trauma [5]. Because survival after major trauma is improving, attention can now be directed towards quality of life after survival [6]. Few studies have been conducted in Scandinavia on long-term QoL outcomes [7,8,9].

In the assessment of long-term trauma outcomes for survivors, not only physical impairments but also mental health needs to be considered. One important mental outcome entity, as demonstrated in many trauma outcome studies, is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [9,10,11].

It is well-known that trauma patients suffer from impaired QoL after major trauma [8, 12,13,14,15,16]. However, available studies have focused on the most severely injured patients (ISS > 15) [9, 15, 17, 18].

Many trauma survivors are young, and their daily activities can be greatly, and sometimes permanently, impacted by the consequences of trauma. Therefore trauma registries should also include data on injury-related disability, as recommended more than a decade ago [19]. The Southern Denmark trauma database contain information from the Utstein template for major trauma [20], but this does not include QoL measures.

Studies of long-term QoL in trauma survivors have identified the Injury Severity Score (ISS) [18, 21], extremity injury [12, 18], age [21, 22], female gender [13], lower socioeconomic status, and living alone as independent predictors of poor quality of life after severe trauma [18]. Furthermore, severely injured patients are known to face a major risk of PTSD [17], which has not been assessed in a Scandinavian trauma setting. PTSD has been reported to predict low QoL and be most commonly present in severely injured patients [23]. We found no study including all patients received by a trauma team, regardless of Injury Severity Score.

Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to assess the long-term quality of life and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) of survivors of trauma and quality of life (QoL) in relation to injury severity and as a secondary aim to study variation between a university and a connected regional centre.

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted in Denmark for a region of 1.2 million in two centres. The university trauma centre serves as the primary facility for a population of around 500,000, and as a secondary referral centre for the whole region. One regional trauma centre serves as the primary facility for a well-defined geographical area with a population of around 300,000. All transfers from the regional centre go to the university centre in this study, when there is an immediate need for higher level treatment.. Two other primary centres were not included.

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (Journal no. 13/32033). Data protection met the standards set by Danish law, which allows patients to be contacted for follow up. The study complied with the ethical and legal regulations in Denmark for clinical studies of this nature.

Study population and data collection:

We included a retrospective cohort consisting of all consecutive patients received by the trauma response teams at the two trauma centres for the full calendar year 2013. Systematic review of patient records and ongoing quality-assureance (completeness and content) for inclusion in the Southern Denmark trauma database secures a consecutive patient series of all patients received by the trauma teams, which is an indication that there was a potential threat to life at the scene. Trauma teams were activated based on a structured criteria for the potential impact of the incident. Data on mortality and current addresses were obtained from the Danish Civil Registration System [24].

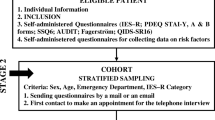

To comply with regulations only patients aged 18 or older, alive at follow-up and with a Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) ≥ 3 were contacted via the questionnaire [25]. Detailed numbers are shown in fig. 1. Questionnaires were sent from November 2014–January 2015 such that patients were contacted either at 12–17 months or 18–24 months after the injury. In addition to QoL and PTSD questionnaires, questions on other aspects were formulated in accordance with The Danish National Health Survey from 2013 [26].

Quality of life

Quality of life was assessed using the European Quality of life questionnaire (EQ-5D) [27], including a Visual Analog Scale (VAS; 0–100 scale) and the five-question items in version EQ-5D-5 L. The questionnaire consists of the following five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression [27, 28].

Each dimension has five levels: no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems, and extreme problems. The ratings for the five dimensions were converted into a single index (the utility score) using population-based preference weights from the Danish population norm [29].

Assessment of PTSD

The civilian version of the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL) was used [30, 31]. The PCL is a 17-item checklist, in which each item has five levels and was assumed positive when scored at level 3 or higher [32]. To diagnose PTSD according to DSM-IV, patients must fulfil 4 criteria (A + B + C + D). Criterion A refers to the occurrence of a stressful event involving life danger and intense fear, horror, and helplessness. Symptoms are described by groups B (requiring ≥1 intrusion symptoms), C (requiring ≥3 avoidance/numbing symptoms), and D (requiring ≥2 hyperarousal symptoms). For this study, we defined PTSD positive as DSM-IV (A + B + C + D) [32] in combination with an overall minimum PCL sum of 37 [33]. It has been translated into Danish and has been used in several studies [34, 35]. Validation studies have demonstrated good psychometric properties, both internationally and in a Danish setting [33].

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical data are presented as either means + 95% confidence interval (CI) or medians + interquartile range (IQR), if not normally distributed for continuous variables. Categorical variables are presented as either proportions with CIs or percentages. Statistical tests were performed according to type of variables and comparisons (Chi-square, t-test, Mann–Whitney U-test, two sample equity of proportions).

The Danish population norm data was used to compare the health status of the patients included in this study. The EQ-5D index score were compared between groups. When QoL was examined, the scores were dichotomized. Low QoL (Low EQ) was defined as being lower than 2 standard deviations below the Danish national norm, and thereby includes the 2.3% with lowest QoL in the Danish population. The proportion of the study population with a QoL equal to the low EuroQoL score in the Danish population was then calculated.

Data entry with double entry verification was performed with EpiData software (www.EpiData.dk) and analysis using STATA (www.stata.com).

Results

Response rates

In 2013, 1048 patients were received by the trauma team at either the university hospital or the regional hospital, and were thus entered into the trauma registry. Approximately, the same number of patients were treated at each hospital (542; 506). Of the 542 patients received at the university hospital, 32 were acute cases transferred from the regional hospital. Details of the inclusion is shown in fig. 1.

A total of 508 (66%) returned the questionnaires and agreed to participate. Differences between responders and nonresponders are presented in Table 1. Nonresponders (n = 266) were younger than responders and more often males (340 vs 202, p = 0.009). More responders than nonresponders had a NISS higher than 15 (346 vs 211, p = 0.001).

The proportion followed up at 12–17 months at the two hospitals was the same (university hospital (0.63; CI 0.57–0.69), regional hospital (0.63; CI 0.56–0.68)). The proportion followed up at 18–24 months at the two hospitals was the same (university hospital (0.37; CI 0.31–0.43), regional hospital (0.37; CI 0.32–0.44)). The response rate in the 12–17-month follow-up group was higher than in the group contacted after 18–24-months.

All items in EQ-5D were answered in 495 questionnaires (97%) and in 461 PCL questionnaires (91%) For 455 patients a completed EQ-5D and PCL questionnaire was received. These were included for analysis.

Pattern of injuries

The most common mechanism of injury was traffic injury. Further analyses of more specific injury types were not conducted due to lack of detailed data.. The median NISS for all respondents was 9 (IQR 2–17), and more than 30% of recruited patients had major trauma (NISS > 15). As expected, median NISS scores at the university hospital were higher than at the regional hospital (12 vs 5, p = 0.000) (Table 2).

In multivariate analysis, injury localization (spinal cord injury and lower extremity injury) was negatively associated with EQ-VAS, EQ index, and PTSD symptoms. The proportion of trauma patients with internal head injuries and an AIS score > 1 was 0.27 (CI: 0.23–0.31). The proportion of spine injuries with an AIS > 1 was 0.20 (CI: 0.17–24) and the proportion of lower extremities injuries with an AIS > 1 was 0.15 (CI: 0.12–0.19).

Health status measurement

The trauma population reported poorer self-rated health than the population norm: “Good, very good or excellent health” 0.654 (CI: 0.608–0.698) (norm: 0.852 (CI: 0.850–0.853)) [26]. Pain and discomfort: “High levels of pain and discomfort” 0.586 (CI: 0.539–0.633) (norm: 0.376 (CI: 0.374–0.378)). This tendency was seen for both males and females. Subjects who reported high levels of pain and discomfort in any dimension (i.e., shoulders, neck, arms, hands, legs, knees, hips, back, or headache) were more frequent in the trauma study population than in the National Health Survey [26].

Quality of life

Of the 455 who answered all EQ-5D dimension items, 67 (15%) reported no problems (State 11,111) on all five dimensions. Of the 3125 possible EQ-5D health states 174 different states were reported. The median visual analogue scale score on the EuroQol (EQ-VAS) was 70 (IQR: 50–85) and the median EQ index score was 0.745 (IQR: 0.599–0.859). The EQ-5D mean values in different age groups are presented in Table 3, according to recommendations from the EuroQol group. All trauma study values are lower than the Danish population norms [29].

The proportion of low EQ index score in this study group was 0.24 (CI: 0.20–0.28) (Table 4). The majority of the variables presented in Table 4 are associated with a high proportion in the low EQ area of the population norm data. There were no difference in proportion of low EQ at the university and the regional hospitals (0.26 vs 0.21, p = 0.25) or the two follow-up groups (0.26 vs 0.20, p = 0.18). But the severly injured had a higher proportion at the low EQ level (0.21 vs 0.31, p = 0.01) for NISS cut at 15. Lower Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) scores were associated with a higher proportion of low EQ (Table 4), Mantel-Haenszel chi-square for linear trend = 14.13, (p < 0.001).

Post-traumatic stress disorder

The proportion of patients with PTSD based on the DSM-IV criteria and a PCL summarized score of 37 or higher, was 0.22 (CI: 0.18–0.26). The proportion of patients with PTSD at follow- up was the same in both centres with university centre at 0.23 (0.17–0.28) and (0.22 (0.17–0.28)) at the regional centre. This also applies to the two follow-up groups (0.24 vs 0.19, p = 0.216).

The level of trauma showed no differences when compared by centre, gender, or age group (Table 4). It is noteworthy, that the proportion of patients with PTSD was not affected when comparing NISS < 15 0.23 (0.19–0.28) and NISS > 15 0.19 (0.13–0.27) (p = 0.345).

Discussion

Low Qol was seen in 24% of these trauma patients and PTSD in 22% at follow-up. No variation in PTSD was seen for centre (university vs regional) or trauma severity (NISS > 15). This high level of impaired QoL and PTSD points to a significant deficit in complete recovery from serious injury and suggests a potential important public health consequence.

The study population represents the complete clinical population with suspected major trauma,as seen in Scandinavian countries—a major strength of our study. However responders vere older, more often female, had a higher NISS, had a longer ICU stay and had a more severe outcome at end of hospital stay (measured by GOS) than nonresponders. Some of these diffences are well known when using questionnaires, but is still considered a limitation.

Most survivors of major trauma continue to suffer from one or more permanent functional consequences in the long-term. This has a negative impact on their QoL, which often remains far below the general population norms [9, 19, 36]. In both Germany and the United Kingdom, there is consensus about recommending a short-term follow-up and one to two long-term follow-ups after major trauma [37]. However, few trauma registries routinely collect information about long-term follow-up. QoL after severe trauma injury can be drastically changed. Unlike the clinical outcome (mortality) typically measured in trauma trials, QoL reflects the impact of the injury from the perspective of the patient. A better understanding of trauma survivors’ perceptions of their QoL and its influencing factors will assist in developing strategies to improve QoL for trauma patients.

The assessment of PTSD in patients with low NISS vs the PTSD of patients with high NISS showed that the proportions with PTSD were equal. Nevertheless, the two NISS groups differed when looking at the proportion with low QoL. Among patients with severe injury (NISS > 15), the proportion with low QoL was higher than among those with low NISS. Hence, PTSD outcome is not affected by severity measured by NISS, whereas QoL is affected by severity measured by NISS.

PTSD was assessed using the PCL checklist, which is a widely recognized and used self-reporting measure reflecting the DSM-IV definition of PTSD. PCL results may be presented in different ways. As demonstrated, in a Danish setting, the approach depends on the purpose [33]. We combined the diagnostic approach of DSM-IV with a cut-off value, instead of using a cut-off value alone, thereby assuring that all dimensions were represented as stated in the diagnostic criteria. The type of cut-off employed has a major impact on the estimated prevalence of PTSD. The majority of the research in Denmark using the PTSD Checklist Civilian questionnaire has been carried out on military samples [33, 35]. The most frequently used cut-off is 44 for diagnostic purposes, a threshold also used in more extensive Danish studies [34]. Higher cut-off scores have been used in highly traumatized samples, while lower cut-off scores have been suggested for screening use.

A general limitation in injury research is the absence of information on preinjury status. The physical status classification system of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) was used to classify all trauma patients. No further measurements were used, however, to assess preinjury status. One approach to this issue could simply be to ask the patient. However, the time lag involved in the retrospective collection of data means that the problems in measurement are not thereby reduced. The retrospective nature of our assessment could have led to recall bias, a well-known issue in injury research [38]. Although there is some variation in the population from expected norm values in terms of education, income, etc., we considered that the application of the comparison to population norms was a relevant approach, and more appropriate than intra-individual retrospective assessment. The large differences shown are most likely real differences, and not a consequence of selective injury occurrence with these factors.

The negative effect of injury severity on trauma outcome is obtained in most current international trauma registries [39, 40]. Other effects of injury might be more subtle or might not appear immediately. This study highlights QoL and PTSD as two of the outcomes worth monitoring after the initial treatment of trauma patients, regardless of injury severity score.

Conclusions

We found that trauma patients from a university and a regional trauma centre showed large proportions of affected QoL and PTSD after 12–24 months in comparison with population norms.

The study supports the understanding that QOL and PTSD are important aspects of patients lives after trauma. Furthermore, the results point to the need for further development and implementation of outcome measures, in terms of both physical and mental health, as well as long-term follow-up on QoL when treating trauma patients. The proportion of patients with evidence of PTSD possibly requiring treatment is 0.22 (0.18–0.26), and the proportion with low QoL compared to the Danish population norm is high 0.24 (CI: 0.20–0.28).

Abbreviations

- ACS:

-

American College of Surgeons

- AIS:

-

Abbreviated Injury Scale

- ASA:

-

Physical status classification system of the American Society of Anesthesiologists

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DSM-IV:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition

- EQ-5D:

-

European Quality of life questionnaire

- EQ-5D-5 L:

-

Five-question items, 5 level, in version of EQ-5D

- EQ-VAS:

-

European Quality of Life Visual Analog Scale

- EuroQoL:

-

European quality of life

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- ISS:

-

Injury Severity Score

- NISS:

-

New injury severity score

- PCL:

-

PTSD Checklist

- PTSD:

-

Post-traumatic stress disorder

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

References

WHO | The global burden of disease: 2004 update. WHO. 2004. http://www.who.int/topics/global_burden_of_disease/en/. Accessed 25 June 2015.

Ringdal KG. Developing a common, international template for docomenting and reporting data from major trauma patients “a proposal core dataset and evaluations of its feasibility and reliability.” dissertation for the degree of philosophiae doctor (PhD): Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo, 2012.

Aitken LM, Chaboyer W, Schuetz M, Joyce C, Macfarlane B. Health status of critically ill trauma patients. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(5/6):704–15.

Dødsårsagsregistreret 2010 Tal og analyse [Cause of Death registry’s annual reports]. 2011. www.sst.dk. (Accessed December 2017).

MacKenzie EJ, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, Nathens AB, Frey KP, Egleston BL, et al. A national evaluation of the effect of trauma-center care on mortality. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:366–78.

Hoffman K, Cole E, Playford ED, Grill E, Soberg HL, Brohi K. Health outcome after major trauma: what are we measuring? PLoS One. 2014;9:e103082.

Overgaard M, Høyer CB, Christensen EF. Long-term survival and health-related quality of life 6 to 9 years after trauma. J Trauma. 2011;71:435–41.

Ringburg AN, Polinder S, van Ierland MCP, Steyerberg EW, van Lieshout EMM, Patka P, et al. Prevalence and prognostic factors of disability after major trauma. J Trauma. 2011;70:916–22.

Kaske S, Lefering R, Trentzsch H, Driessen A, Bouillon B, Maegele M, et al. Quality of life two years after severe trauma: a single Centre evaluation. Injury. 2014;45(3):S100–5.

Delft-Schreurs C, Bergen J, Sande P, Verhofstad M, Vries J, Jongh MA. Cross-sectional study of psychological complaints and quality of life in severely injured patients. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:1353–62.

Hours M, Chossegros L, Charnay P, Tardy H, Nhac-Vu H-T, Boisson D, et al. Outcomes one year after a road accident: results from the ESPARR cohort. Accid Anal Prev. 2013;50:92–102.

Holbrook TL, Anderson JP, Sieber WJ, Browner D, Hoyt DB. Outcome after major trauma: discharge and 6-month follow-up results from the trauma recovery project. J Trauma. 1998;45:315–23. discussion 323-324

Holbrook TL, Hoyt DB. The impact of major trauma: quality-of-life outcomes are worse in women than in men, independent of mechanism and injury severity. J Trauma. 2004;56:284–90.

Tøien K, Bredal IS, Skogstad L, Myhren H, Ekeberg O. Health related quality of life in trauma patients. Data from a one-year follow up study compared with the general population. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2011;19:22.

Gabbe BJ, Sutherland AM, Hart MJ, Cameron PA. Population-based capture of long-term functional and quality of life outcomes after major trauma: the experiences of the Victorian state trauma registry. J trauma Inj infect. Crit Care. 2010;69:532–6.

Christensen MC, Banner C, Lefering R, Vallejo-Torres L, Morris S. Quality of life after severe trauma: results from the global trauma trial with recombinant factor VII. J Trauma. 2011;70:1524–31.

Baranyi A, Leithgöb O, Kreiner B, Tanzer K, Ehrlich G, Hofer HP, et al. Relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder, quality of life, social support, and affective and dissociative status in severely injured accident victims 12 months after trauma. Psychosomatics. 2010;51:237–47.

Janssen DC, Ommen O, Neugebauer E, Lefering R, Pfaff H. Predicting health-related quality of life of severely injured patients: sociodemographic, economic, trauma, and hospital stay-related determinants. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2008;34:277–86.

Vles WJ, Steyerberg EW, Essink-Bot M-L, van Beeck EF, Meeuwis JD, Prevalence LLPH. Determinants of disabilities and return to work after major trauma. J Trauma. 2005;58:126–35.

Ringdal K, Coats T, Lefering R, Bartolomeo SD, Steen P, Røise O, et al. The Utstein template for uniform reporting of data following major trauma: a joint revision by SCANTEM, TARN, DGU-TR and RITG. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2008;16:7.

Aitken LM, Davey TM, Ambrose J, Connelly LB, Swanson C, Bellamy N. Health outcomes of adults 3 months after injury. Injury. 2007;38:19–26.

Richmond TS, Kauder D, Hinkle J, Shults J. Early predictors of long-term disability after injury. Am J Crit Care. 2003;12:197–205.

Michaels AJ, Michaels CE, Smith JS, Moon CH, Peterson C, Long WB. Outcome from injury: general health, work status, and satisfaction 12 months after trauma. J Trauma. 2000;48:841–8. discussion 848-850

Pedersen CB. The Danish civil registration system. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7):22–5.

Jennett B, Bond M. Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage. Lancet Lond Engl. 1975;1:480–4.

Danskernes Sundhed (in Danish) [The Danish National Health Survey]. http://www.danskernessundhed.dk/. (Accessed 22 May 2018).

EuroQol Group. EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy Amst Neth. 1990;16:199–208.

Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy Amst Neth. 1996;37:53–72.

Sørensen J, Davidsen M, Gudex C, Pedersen KM, Brønnum-Hansen H, Danish EQ. 5D population norms. Scand J Public Health. 2009;37:467–74.

Weathers F, Litz B, Herman D, Huska J, Keane T. The PTSD checklist (PCL): reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. 1993.

Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL). Behav Res Ther. 1996;34:669–73.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. In: Text revision. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Karstoft K-I, Andersen SB, Bertelsen M, Madsen T. Diagnostic accuracy of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist–civilian version in a representative military sample. Psychol Assess. 2014;26:321–5.

Berntsen D, Rubin DC. When a trauma becomes a key to identity: enhanced integration of trauma memories predicts posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Appl Cogn Psychol. 2007;21:417–31.

Madsen T, Karstoft K-I, Bertelsen M, Andersen SB. Postdeployment suicidal ideations and trajectories of posttraumatic stress disorder in Danish soldiers: a 3-year follow-up of the USPER study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75:994–1000.

Holtslag HR, van Beeck EF, Lichtveld RA, Leenen LP, Lindeman E, Individual v d WC. Population burdens of major trauma in the Netherlands. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:111–7.

Ardolino A, Sleat G, Willett K. Outcome measurements in major trauma--results of a consensus meeting. Injury. 2012;43:1662–6.

Rivollier F, Peyre H, Hoertel N, Blanco C, Limosin F, Delorme R. Sex differences in DSM-IV posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms expression using item response theory: a population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2015;187:211–7.

Sleat GKJ, Ardolino AM, Willett KM. Outcome measures in major trauma care: a review of current international trauma registry practice. Emerg Med J. 2011;28:1008–12.

Holtslag HR, Post MW, Lindeman E, Van der Werken C. Long-term functional health status of severely injured patients. Injury. 2007;38:280–9.

Funding

We deeply acknowledge the members of The Danish foundation Tryg Fonden for funding part of the scholarships of the PhD students Frederik Borup Danielsson. The study sponsor did not have any involvement in the study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study will be anonymised and available when paper has been published and will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to all of the following: 1. the conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, 2. drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, 3. final approval of the version to be submitted. The manuscript, including related data, figures and tables has not been previously published and is not under consideration elsewhere. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (Journal no. 13/32033). Data protection met the standards set by Danish law, which allows patients to be contacted for follow up. The study complied with the ethical and legal regulations in Denmark for clinical studies of this nature.

Competing interests

The authors state that there is no conflicts of interest. The authors declare that they have no competing interest in the performance of the study.

Authors have no disclosure or any financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence (bias) this work.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Danielsson, F.B., Schultz Larsen, M., Nørgaard, B. et al. Quality of life and level of post-traumatic stress disorder among trauma patients: A comparative study between a regional and a university hospital. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 26, 44 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-018-0507-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-018-0507-0