Abstract

Background

Foamy viruses (FVs) are retroviruses with unique replication strategies that cause lifelong latent infections in their hosts. FVs can also produce foam-like cytopathic effects in vitro. However, the effect of host cytokines on FV replication requires further investigation. Although interferon induced transmembrane (IFITMs) proteins have become the focus of antiviral immune response research due to their broad-spectrum antiviral ability, it remains unclear whether IFITMs can affect FV replication.

Method

In this study, the PFV virus titer was characterized by measuring luciferase activity after co-incubation of PFVL cell lines with the cell culture supernatants (cell-free PFV) or the cells transfected with pcPFV plasmid/infected with PFV (cell-associated PFV). The foam-like cytopathic effects of PFV infected cells was observed to reflect the virus replication. The total RNA of PFV infected cells was extracted, and the viral genome was quantified by Quantitative reverse transcription PCR to detect the PFV entry into target cells.

Results

In the present study, we demonstrated that IFITM1-3 overexpression inhibited prototype foamy virus (PFV) replication. In addition, an IFITM3 knockdown by small interfering RNA increased PFV replication. We further demonstrated that IFITM3 inhibited PFV entry into host cells. Moreover, IFITM3 also reduced the number of PFV envelope proteins, which was related to IFITM3 promoted envelope degradation through the lysosomal pathway.

Conclusions

Taken together, these results demonstrate that IFITM3 inhibits PFV replication by inhibiting PFV entry into target cells and reducing the number of PFV envelope.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Foamy viruses (FVs) belong to the Spumaretrovirinae subfamily of Retroviridae, and their replication strategy is intermediate between the Hepadnaviridae and Retroviridae. [1, 2]. Envelope proteins are essential for FV replication and the budding of FVs is strictly envelope glycoprotein-dependent since their Gag proteins lack membrane-targeting signals and must interact with envelope proteins for membrane-targeting ability [3, 4]. Similar to the hepatitis B virus S protein, FVs release Env-only subviral particles [3]. FVs have a wide range of hosts and infect primates, felines, bovines, and equines [5,6,7,8]; however, there have been few studies on the effects of cellular factors on FV replication.

The innate immune response plays an important role in antiviral therapy. Interferon (IFN)-induced transmembrane proteins (IFITMs) are activated by the interferon stimulating genes (ISGs), which have recently become an area of research focus on the antiviral immune response due to their broad-spectrum antiviral effects [9]. At present, there are five genes encoding IFITM proteins in humans, including IFITM1, IFITM2, IFITM3, IFITM5, and IFITM10 [10]. IFITM1-3 proteins can be significantly upregulated by IFNs and are ubiquitously expressed in human tissues in the absence of IFN induction; however, IFITM5 and IFITM10 protein expression was not induced by IFN [11]. IFITM1, IFITM2, and IFITM3 play a role in embryonic development, signal transduction, tumorigenesis, and antiviral activities [12, 13]. IFITM5, which is involved in bone mineralization and maturation, is only expressed in osteoblasts, whereas the function of IFITM10 remains unclear [14, 15]. Some other species have been reported to exhibit homologous genes in the IFITM family, suggesting that IFITMs have important and conserved functions [16].

At present, the antiviral spectrum of IFITMs encompasses over 20 viruses from 12 families [15]. These include DNA viruses, enveloped RNA viruses and non-enveloped RNA viruses [17,18,19]. There are several viruses with severe pathogenicity in humans that are inhibited by IFITMs, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [20], Ebola virus (EBOV) [21], influenza A virus (IAV) [22, 23], Zika Virus (ZIKV) [24] and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) [25]. Among those with antiviral activity, IFITM3 is the best characterized [26]. Moreover, there are some viruses that are not inhibited by IFITMs, including murine leukemia virus (MLV) [27], adeno-associated virus (AAV) [28], lymphocytic choroid plexus bacterial meningitis (LCMV) [29], and arenavirus (LASV) [15]. Further research is required to clarify the molecular mechanisms underlying IFITM antiviral activity and why some viruses can escape IFITM inhibition.

At present, the comprehensive antiviral mechanism of IFITM primarily includes IFITM-mediated inhibition of viral entry by inhibiting viral fusion to the plasma membranes and lysosomal or endosomal membranes, rather than relying on specific recognition of viral components to restrict virus entry [9, 26]. IFITM proteins can also regulate the endosomal or lysosomal pH [30]. The conformation of some viral envelope proteins (e.g., hemagglutinin) changes at a low endosomal pH, mediating hemifusion of viral and endosomal membranes [31]. In addition, IFITM3 can inhibit the replication of some non-enveloped viruses by regulating the function of late endosomes [18]. IFITMs have also been demonstrated to reduce the infectivity of some newly generated viruses. For example, IFITM proteins can be colocalized with HIV-1 Env and Gag and become part of the nascent generated virus particles, inhibiting virion entry into new host cells [20]. Recently, IFITM proteins have been found to inhibit HIV-1 protein synthesis and thus limit viral infection [32]. Prototype foamy virus (PFV) is a type of FV. However, whether the replication of PFV, an enveloped virus that entry target cells in a pH-dependent manner [33], is affected by IFITMs remains unclear. In this study, we demonstrated that IFITM1-3 inhibits PFV replication by inhibiting PFV entry and reducing the number of PFV envelope protein.

Materials and methods

Plasmid constructs

Full-length infectious clone of PFV (pcPFV) was kindly provided by Maxine L. Linial (Division of Basic Sciences, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA) [34]. The pCMV-Tag2B-Tas plasmid was constructed by inserting the 9434 to 10,336 nucleotide region containing orf1 into pCMV-Tag2B. HA-tagged IFITM1-3 eukaryotic expression plasmids were constructed by inserting the cDNA of human IFITM1, IFITM2, and IFITM3 into pCMV-3HA vectors (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). Insert the cDNA encoding human IFITM3 into pQCXIP-Flag vector to construct a pQCXIP-Flag-IFITM3 plasmid. The PFV envelope encoding sequence was inserted into pCMV-3HA or pCE-puro-3×FLAG to construct the pCMV-3HA-Env or pCE-puro-3×Flag-Env plasmid. The pEGFP-C3 vector was purchased from BD Biosciences (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). A pair of double-stranded oligonucleotides targeting IFITM3 was inserted into the pSIREN-RetroQ vector (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) to obtain the pSIREN-RetroQ-shIFITM3 plasmid.

Cell culture and transfection

Human embryonic kidney (HEK293T), PFVL (BHK21-derived indicator cell lines containing the luciferase gene initiated by the PFV LTR) [35], HT1080, and HeLa cells were incubated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Plasmid transfection was performed using polyethyleneimine (PEI, Polysciences, Warrington, PA, USA) reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions [36].

Virus production and infection

The pcPFV plasmid was transfected into HEK239T cells and the cell culture supernatant was collected 48 h after transfection and filtered through a 0.45 µm filter to obtain the PFV virus stock solution, which can be stored at 4℃. PFV viral titers were measured by infection of PFVL cells [37]. Target cells were infected with the virus stock and fresh culture medium was replaced at 8 h post-infection. After 48 h of infection, 1/20 of the infected cells or 500 µL of cell culture supernatant were co-incubated with PFVL cells to test the infectivity of the virus produced by replication in target cells. The levels of PFV protein expression in the infected cells were analyzed by Western blotting.

Generation of knockdown cell lines

We used small hairpin RNA (shRNA) to screen IFITM3 knockdown cell lines. The target sequences of IFITM3 shRNA and control shRNA were 5′-TCCCACGTACTCCAACTTCCA-3′ and 5′-GAAGTAAGCGATATACATA-3′, respectively. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with 1 µg pSIREN-RetroQ-shIFITM3 or pSIREN-RetroQ-shControl plasmids, 1 µg pMVL-Gag/Pol, and 0.5 µg pVSV-G. HT1080 cells were infected with the cell culture supernatants at 48 h after transfection. At 48 h post-infection, knockdown HT1080 cells were selected by medium containing puromycin (2 μg/mL). The following primer sequences were used to detect IFITMs mRNA levels in HT1080-shIFITM3 cells by qPCR: IFITM1-up: 5′-ATCCTGTTACTGGTATTCGG-3′; IFITM1-low: 5′-TATAAACTGCTGTATCTAGG-3′; IFITM2-up: 5′-GTTGGTCGTCCAGGCCCAGC-3′; IFITM2-low: 5′-CTGTGGGGACAGGGCGAGGA-3′; IFITM3-up: 5′-GCTGATCTTCCAGGCCTATG-3′; IFITM3-low: 5′-GATACAGGACTCGGCTCCGG-3′.

Luciferase reporter assay

Following a co-incubation with cell culture supernatants (containing virus particles) or PFV-infected cells, luciferase levels of PFVL cells were determined using a luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The corresponding results were the average of three independent experiments.

Alu-PCR

HT1080 cells transfected with IFITM3 expression plasmid or control vector were infected with the PFV virus stock, and the total DNA of infected cells was extracted using a DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Duesseldorf, Germany) 30 h post-infection. Cells treated with 10 µM of the integrase inhibitor raltegravir or 10 µM of the reverse transcriptase inhibitor AZT were used as controls, the degree of PFV genome integration was detected by semi-quantitative PCR and real-time PCR using Alu-PCR primers.

The extracted total DNA (100 ng) was used as template, and 10 µM of Alu1, Alu2 and SpA primers were added for PCR. PCR conditions were 95 °C for 5 min for 1 cycle; 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 68 °C for 3 min, for 22 cycles; 68 °C for 7 min for 1 cycle. Next 2 µL PCR products were used as the template, and 10 µM Lambda and Nested-R primers were added for the second PCR. PCR conditions were: 95 °C for 5 min for 1 cycle; 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 68 °C for 30 s, for 22 cycles; 68 °C for 7 min for 1 cycle. Using the extracted total DNA as a template, the gapdh gene was amplified as a control. PCR conditions were 95 °C for 5 min for 1 cycle, 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 68 °C for 30 s, for 22 cycles, and 68 °C for 7 min for 1 cycle. The following primer sequences were used: SpA: 5′-ATGCCACGTAAGCGAAACTTAGTATAATCATTTCCGCTTTCG-3′; GAPDH-up: 5′-AACAGCGACACCCACTCCTC-3′, GAPDH-low: 5′-CATACCAGGAAATGAGCTTGACAA-3′; Lambda: 5′-ATGCCACGTAAGCGAAACT-3′; NestedR: 5′-GAAACTAGGGAAAACTAGG-3′; Alu1: 5′-TCCCAGCTACTGGGGAGGCTGAGG-3′, Alu2: 5′-GCCTCCCAAAGTGCTGGGATTACAG-3′.

Western blotting

The cell lysates were placed on ice for 30 min after adding lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 3% Glycerol, 2 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl) to the cell samples to be tested. The proteins were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and subsequently transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (GE Healthcare, Cincinnati, OH, USA). The PVDF membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk for 45 min, after which the PVDF membrane was incubated with primary antibodies for 1.5 h and incubated with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 45 min. Immunoreactive protein signals were detected by chemiluminescence (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany).

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used in the protein detection analysis in this study: polyclonal rabbit anti-IFITM3 (1:2000; cat. no. 11714-1-AP, Proteintech, Chicago, IL, USA), monoclonal mouse anti-HA (1:3000; cat. no. H3663, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), monoclonal mouse anti-GFP (1:2000; cat. no. sc-9996, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), monoclonal mouse anti-Tubulin (1:5000; cat. no. sc-32293, Santa Cruz), monoclonal mouse anti-GAPDH (1:5000; cat. no. sc-47724, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:5000; cat. no. sc-2005, Santa Cruz), and HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:5000; cat. no. sc-2004, Santa Cruz), and monoclonal mouse anti-Flag (1:5000; cat. no. F1804, Sigma-Aldrich) antibodies. We use purified Tas or PFV Gag (180–433 aa) proteins as immunogens to immunize BALB/c mice to obtain antibodies against the corresponding proteins. Since part of the Bet protein overlaps with the 88 amino acids at the N terminus of the Tas protein, the Bet protein can be detected using anti-serum prepared with the Tas protein as an immunogen.

Virus entry assay

HT1080 cells were infected with a PFV stock solution and incubated at 4℃ for 1 h to ensure virus attachment to the cell membrane surface but not entry into cells. The cells were washed with PBS to remove any unattached virus, and the cells were cultured at 37℃ after replacing the culture medium. After 0 h, 2 h, 4 h 6 h and 8 h, the cells were harvested to extract the total RNA from the infected cells. The number of viral genomes in the cells was detected by RT-qPCR to indicate the level of viral entry. The amount of viral genome was indicated by the level of Gag gene expression. The following primers were used for RT-qPCR: Gag forward (5′-AATAGCGGGCGGGGACGACA-3′), Gag reverse (5′-ATTGCCACGCACCCCAGAGC-3′); GAPDH forward (5′-AACAGCGACACCCACTCCTC-3′), GAPDH reverse (5′-CATACCAGGAAATGAGCTTGACAA-3′).

Statistical analysis

The data were presented as the mean ± standard deviations (SD) of the results of three independent experiments. The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism Version 8.0 (GraphPad software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). When the P value was greater than 0.05, the difference was not significant (ns). A P value less than 0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001).

Results

IFITM3 inhibits PFV entry into HT1080 cells

Studies have shown that IFITM proteins can broadly inhibit the entry of a variety of viruses into target cells [21, 26, 38, 39]. Whether IFITM3 affects the entry of PFV has not been reported. To clarify whether IFITM3 inhibits early step in the PFV life cycle, we first examined whether IFITM3 affected the PFV genome integration. The integration of the PFV genome into PFV-infected cells was detected by Alu-PCR. Based on the principle of Alu-PCR, the integrated PFV genome was detected using semi-quantitative PCR (Fig. 1A) and real-time PCR (Fig. 1B), respectively. As shown in the Fig. 1A, B, the GAPDH band intensity was similar in all experimental groups. PFV genome integration was inhibited following treatment with raltegravir (an integrase inhibitor) or AZT (a reverse transcriptase inhibitor). In addition, the degree of integration of PFV in the IFITM3 overexpression group under the treatment of these two inhibitors was the same as that of the respective control group. IFITM3 overexpression inhibited PFV genome integration when without inhibitor treatment. These results suggested that IFITM3 might influence PFV integration and some steps prior to integration during replication.

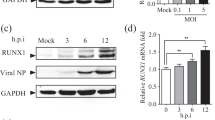

IFITM3 inhibits PFV entry into HT1080 cells. HT1080 cells were infected with the PFV virus stock solution (2 MOI) 24 h after transfection of IFITM3 expression plasmid or control vector, and total DNA was extracted 30 h after infection. The semiquantitative PCR (A) and real-time PCR (B) results indicate the level of proviral DNA integration. C The levels of PFV entry were evaluated as described in the Materials and Methods. The amount of PFV Gag gene relative to gapdh indicates the level of viral mRNA. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Values were statistically evaluated using a two-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Error bars represent the standard deviations

Therefore, we next explored whether IFITM3 affects PFV entry into target cells by first infecting HT1080-shNC or HT1080-shIFITM3 cells with PFV virus stock solution. The degree of viral entry into the cells was measured at various time points post-infection. As shown in Fig. 1C, after a 6 h culture at 37℃, the level of PFV entry in the IFITM3 knockdown cells was higher than that in the control group, demonstrating that IFITM3 inhibited PFV entry into HT1080 cells.

An IFITM3 knockdown promotes PFV replication

To further clarify the inhibitory effect of IFITM3 on PFV replication, we examined the effect of an IFITM3 knockdown on PFV replication. The level of endogenous IFITM3 in HT1080 and HeLa cells was similar, which was higher than that in HEK293T cells (Fig. 2A). We screened HT1080 cell lines with an endogenous IFITM3 knockdown, due to the high sequence similarity of IFITM1, IFITM2 and IFITM3, to ensure that IFITM3 knockdown was specific, we detected the mRNA levels of IFITM1, 2 and 3 in HT1080-shIFITM3 cell line. As shown in the Additional file 1: Fig. S1, the knockdown of IFITM3 in HT1080-shIFITM3 cells was specific, IFITM3 knockdown did not affect the mRNA levels of IFITM1 and IFITM2. IFITM3 knockdown HT1080 cells were infected with a PFV viral stock solution. At 48 h post-infection, the PFVL cell lines were incubated with the cell culture supernatant or infected HT1080 cells. The levels of viral protein in the HT1080 cells were also detected. After a 48 h incubation, the luciferase activity in PFVL cells was measured. An IFITM3 knockdown was found to enhance PFV replication in HT1080 cells (Fig. 2B–D). This finding indicated that endogenous IFITM3 inhibited PFV replication, which was consistent with the results of Fig. 1.

IFITM3 knockdown promotes PFV replication. A Levels of IFITM3 protein expression in HT1080, HEK293T, and HeLa cells. B and C Infection of HT1080-shNC or HT1080-shIFITM3 cells with a PFV virus stock solution (0.49 MOI). At 48 h post-infection, the PFVL indicator cell lines were co-incubated with cell culture supernatants (1/2 µL) or HT1080 cells (1/20). The level of luciferase activity was measured at 48 h after co-incubation (values were statistically evaluated using t tests. compared with shNC + PFV group, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). Error bars represent the standard deviations. D The level of PFV proteins in HT1080 cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments

IFITM3 inhibits PFV passaging in HT1080 cells

PFV infection of cultured cells induces severe cytopathic effects (CPE) [40]. To more visually reflect the effect of IFITM3 on PFV replication, we infected IFITM3 knockdown or control HT1080 cell lines with a PFV virus stock solution, and observed the state of the cells at different time points following infection. As shown in Fig. 3A, B, both the shNC and shIFITM3 cells showed foam-like cytopathic (syncytium formation) effects to a certain extent at 36 h post-infection, the syncytia of the shNC and shIFITM3 cell lines increased at 48 h post-infection, and the syncytia production of shIFITM3 cell lines at 36 h and 48 h post-infection was stronger than that of shNC cell lines.

Knockdown of IFITM3 promotes the passage of PFV. A HT1080-shNC or HT1080-shIFITM3 cells were infected with the PFV virus stock (0.49 MOI). The cellular state and pathological changes were observed using an electron microscope at different time points following viral infection. The white arrows indicate syncytium. B The number of syncytia in multiple random fields 36 h after virus infection in A was counted. A total of 12 fields of view were included in three independent experiments. C, D HT1080-shNC or HT1080-shIFITM3 cells were infected with the PFV virus stock (0.17 MOI). Every 2 days following infection, the PFVL indicator cell lines were co-incubated with cell culture supernatants (1/2 µL) or HT1080 cells (1/20). Infected cells (0.03 × 106) were supplemented with 10 times the number of uninfected shNC or shIFITM3 cells. The measured luciferase level of PFVL after co-incubation indicated the titer of the virus after passaging. Values were statistically evaluated using t tests. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Data are representative of two (C, D) or three (B) independent experiments

We further examined the passage of PFV in shNC or shIFITM3 cell lines. Upon PFV infection of shNC or shIFITM3 HT1080 cell lines, the cell culture supernatant and infected HT1080 cells were harvested every 48 h and incubated with the PFVL indicator cell lines. Luciferase activity was measured after an incubation for two days. A total of 0.03 × 106 infected HT1080 cells were retained and 10 times the number of uninfected shNC or shIFITM3 cells were supplemented. The titer of the viral passage was indicated by the level of luciferase activity as measured every 48 h. As shown in Fig. 3C, D, little difference was observed in the PFV titer between shNC and shIFITM3 cells at the beginning of the passage. However, starting from day 4, the PFV virus titer passage in the shIFITM3 cells was significantly higher than that in the control group. These results further confirmed the inhibition of PFV replication by IFITM3.

IFITMs overexpression inhibits the late step of PFV replication

The IFITM proteins were reported to inhibit the late step of feline foamy virus (FFV) replication [41]. To investigate whether IFITM proteins have an effect on the late step of PFV replication, pcPFV and IFITM1, IFITM2, or IFITM3 plasmids were cotransfected into HEK293T cells (the effect of IFITMs on PFV entry was excluded). At two days post-transfection, PFVL indicator cell lines were incubated with the cell culture supernatants (cell-free PFV) or the transfected HEK293T cells (cell-associated PFV). Luciferase activity was detected following 48 h incubation to indicate PFV replication. At the same time, the level of viral proteins in the transfected HEK293T were detected. In Fig. 4A, B, IFITM overexpression significantly reduced luciferase activity, indicating decreased cell-free and cell-associated PFV. Correspondingly, the levels of PFV Bet and Gag protein expression were also significantly reduced in transfected HEK293T cells (Fig. 4C). We performed the same experiments in HT1080 cells and obtained similar results (Fig. 4D–F). Taken together, these results indicate that IFITM1, IFITM2 or IFITM3 overexpression inhibited the late step of PFV replication.

IFITMs overexpression inhibits the late step of PFV replication. A, B The pcPFV was co-transfected into HEK293T cells with IFITM eukaryotic expression plasmids or control vector, respectively. At 48 h post-transfection, the PFVL indicator cell lines were co-incubated with cell culture supernatants (1/2) or transfected HEK293T (1/20) cells. The level of luciferase was measured 48 h after co-incubation. Values were statistically evaluated using one-way ANOVA. Compared with the pcPFV and control vector co-transfection group: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Error bars represent the standard deviations. C The level of PFV protein expression in transfected HEK293T cells. D–F We performed the above experiments in HT1080 cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments

IFITM3 inhibits the amount of PFV envelope protein by degrading it through the lysosomal pathway

The results in Fig. 4 showed that IFITM1, IFITM2 or IFITM3 overexpression inhibited PFV replication in virus-producing cells to similar degrees. Studies have shown that IFITM3 can reduce the abundance of retroviral envelope proteins [42]. Therefore, we detected the effect of IFITM3 on PFV envelope protein expression. IFITM3 reduced the number of PFV envelope protein without affecting the number of the PFV regulatory protein, Tas (Fig. 5A). We then co-transfected the envelope and GFP plasmids with a certain amount of IFITM3. As shown in Fig. 5B, IFITM3 reduced the number of envelope protein without affecting the level of GFP protein expression. This result indicated that the effect of IFITM3 on the PFV envelope protein is specific. The reduction in envelope protein expression by IFITM3 was dose-dependent, and a small amount (10 ng) of IFITM3 was sufficient to significantly reduce the number of the PFV envelope protein. To detect whether the influence of IFITM3 on the number of PFV envelope was related to the degradation, we examined the effect of IFITM3 on envelope expression following treatment with MG132 (a proteasome inhibitor) or Chloroquine (CQ, an inhibitor of lysosomal acidity and function). As shown in Fig. 5C, D, under DMSO or MG132 treatment, IFITM3 could significantly reduce the levels of envelope, whereas IFITM3 only had a minor effect on the number of PFV envelope under CQ treatment. These results suggest that the reduction of envelope by IFITM3 is correlated with degradation through the lysosomal pathway.

IFITM3 reduces the amount of the PFV envelope protein. A HEK293T cells were co-transfected with plasmids encoding for the PFV envelope or Tas protein with HA-IFITM3 or control vector, respectively. The level of intracellular protein expression was detected at 48 h post-transfection. B Flag-Env and GFP-C3 plasmids were co-transfected with HA-IFITM3 or control vector in HEK293T cells. The level of protein expression was detected at 48 h post-transfection. C HEK293T cells were co-transfected with HA-Env and Flag-IFITM3 or control vector. At 30 h post-transfection, the cells were treated with DMSO (100 µM), MG132 (10 µM), or CQ (100 µM). The level of protein expression was detected at 48 h post-transfection. D Quantification of Env protein levels in C. Mean values and standard deviations of Env proteins corrected for Tubulin levels (n = 3) are shown. Values were statistically evaluated using a two-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001

Discussion

At present, IFITMs have been demonstrated to antagonize a variety of viruses, including several serious pathogenic viruses, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [43], Ebola virus (EBOV) [21], and Zika Virus (ZIKV) [24]. In addition, there are some viruses that are able to escape the confinement of IFITMs, such as murine leukemia virus (MLV) [27], adeno-associated virus (AAV) [28] and arenavirus (LASV) [15]; however, the antiviral properties of IFITMs and the reason that some viruses are able to evade inhibition by IFITMs remain unclear. Further research on the effect of IFITMs on diverse viral replication will help clarify the antiviral mechanism of IFITMs.

In this study, we demonstrated that IFITM1-3 could significantly inhibit PFV, and interestingly they inhibited PFV to a similar degree. Previous studies have shown that different IFITMs tend to inhibit the same virus to different degrees. For example, compared with IFITM1 and IFITM2, IFITM3 has a significantly strong effect on influenza A virus (IAV) [23] and IFITM3 can inhibit Zika virus (ZIKV) replication more effectively than IFITM1 [24]. Moreover, the degree of HIV-1 inhibition varies among IFITM members (IFITM3 > IFITM2 > IFITM1) [20], and is related to many factors. Such factors include physiological and biochemical characteristics of IFITMs (e.g., the differences in IFITM localization) and the molecular characteristics of virus replication (e.g., the position of the virus entering the target cell). A similar degree of PFV-mediated inhibition by IFITM1-3 may be related to the unique replication strategy of PFV, the specific mechanism of which requires further study.

IFITM1, IFITM2 and IFITM3 have been reported to inhibit syncytia formation and cell–cell fusion induced by a several classes viral fusion proteins, and the degree of inhibition depends on the cell type [44]. In this study, we reported that IFITM3 also inhibited syncytium formation induced by PFV infection in HT1080 cells. IFITMs can inhibit the entry of a variety of viruses, most of which are viruses that enter cells in a pH-dependent manner. As a virus that enters cells in a pH-dependent manner [33], IFITM3 also inhibits PFV entry into host cells. Studies have shown that IFITM1 is primarily localized at the plasma membrane, whereas IFITM2 and IFITM3 are more localized to intracellular compartments and co-localize with lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1), Rab7, or CD63 [9, 45]. Moreover, PFV Env-mediated fusion occurs at both the plasma membrane and in endosomes [46]. Therefore, although IFITM3 is more likely to inhibit PFV fusion in the endosomal membrane, the specific mechanism requires further exploration. Considering that IFITM1, IFITM2, and IFITM3 have a strong inhibitory effect on PFV replication, further investigation is warranted regarding whether IFITM1 can inhibit PFV fusion in the plasma membrane and whether IFITM2 inhibits PFV fusion in endosomes.

For FVs, envelope glycoprotein mediates viral entry into host cells and are also essential for viral budding [3]. The IFITM proteins were reported to inhibit the late step of feline foamy virus (FFV) replication without effect on early entry step, but the exact mechanism remains unclear [41]. In this study, we also found that IFITM3 downregulated the number of PFV envelope protein, and this reduction was associated with IFITM3 promoting envelope protein degradation via the lysosomes. These results suggest that, unlike FFV, IFITM3 inhibits both PFV entry into target cells and late step in the PFV life cycle. Previous studies have shown that IFITM3 can impair the processing of the HIV-1 envelope protein and degrades the envelope protein through lysosomes [42, 47]; however, the Ebola glycoprotein is insensitive to IFITM3 [42], suggesting that not all viral glycoproteins inhibited by IFITMs are affected by IFITMs.

Overall, these results suggest that in addition to inhibiting PFV entry, IFITM3 also reduces the abundance of envelope proteins that are essential for viral replication, and PFV can be inhibited via these two mechanisms.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides the first experimental evidence that IFITM1-3 can inhibit PFV, broadening the antiviral spectrum of IFITMs. We further demonstrate that IFITM3 could not only inhibit PFV entry into target cells but also reduce the abundance of PFV envelope protein, thereby providing insight into the comprehensive antiviral mechanism of IFITMs.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- FVs:

-

Foamy viruses

- PFV:

-

Prototype foamy virus

- IFITMs:

-

Interferon induced transmembrane

- IFN:

-

Interferon

- ISGs:

-

Interferon stimulating genes

- HIV:

-

Including human immunodeficiency virus

- EBOV:

-

Ebola virus

- IAV:

-

Influenza A virus

- ZIKV:

-

Zika virus

- SARS-CoV:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus

- MLV:

-

Murine leukemia virus

- AAV:

-

Adeno-associated virus

- LCMV:

-

Lymphocytic choroid plexus bacterial meningitis

- LASV:

-

Arenavirus

- IAV:

-

Including influenza A virus

- CPE:

-

Cytopathic effects

References

Rethwilm A. The replication strategy of foamy viruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2003;277:1–26.

Linial ML. Foamy viruses are unconventional retroviruses. J Virol. 1999;73:1747–55.

Hutter S, Zurnic I, Lindemann D. Foamy virus budding and release. Viruses. 2013;5:1075–98.

Eastman SW, Linial ML. Identification of a conserved residue of foamy virus Gag required for intracellular capsid assembly. J Virol. 2001;75:6857–64.

Broussard SR, Comuzzie AG, Leighton KL, Leland MM, Whitehead EM, Allan JS. Characterization of new simian foamy viruses from African nonhuman primates. Virology. 1997;237:349–59.

Hatama S, Otake K, Omoto S, Murase Y, Ikemoto A, Mochizuki M, Takahashi E, Okuyama H, Fujii Y. Isolation and sequencing of infectious clones of feline foamy virus and a human/feline foamy virus Env chimera. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:2999–3004.

Tobaly-Tapiero J, Bittoun P, Neves M, Guillemin MC, Lecellier CH, Puvion-Dutilleul F, Gicquel B, Zientara S, Giron ML, de The H, Saib A. Isolation and characterization of an equine foamy virus. J Virol. 2000;74:4064–73.

Johnson RH, Oginnusi AA, Ladds PW. Isolations and serology of bovine spumavirus. Aust Vet J. 1983;60:147.

Liao Y, Goraya MU, Yuan X, Zhang B, Chiu SH, Chen JL. Functional involvement of interferon-inducible transmembrane proteins in antiviral immunity. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1097.

Siegrist F, Ebeling M, Certa U. The small interferon-induced transmembrane genes and proteins. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011;31:183–97.

Zhao X, Li J, Winkler CA, An P, Guo JT. IFITM genes, variants, and their roles in the control and pathogenesis of viral infections. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:3228.

Yanez DC, Ross S, Crompton T. The IFITM protein family in adaptive immunity. Immunology. 2020;159:365–72.

Bailey CC, Zhong G, Huang IC, Farzan M. IFITM-family proteins: the cell’s first line of antiviral defense. Annu Rev Virol. 2014;1:261–83.

Hanagata N, Li X, Morita H, Takemura T, Li J, Minowa T. Characterization of the osteoblast-specific transmembrane protein IFITM5 and analysis of IFITM5-deficient mice. J Bone Miner Metab. 2011;29:279–90.

Ren L, Du S, Xu W, Li T, Wu S, Jin N, Li C. Current progress on host antiviral factor IFITMs. Front Immunol. 2020;11:543444.

Hickford D, Frankenberg S, Shaw G, Renfree MB. Evolution of vertebrate interferon inducible transmembrane proteins. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:155.

Perreira JM, Chin CR, Feeley EM, Brass AL. IFITMs restrict the replication of multiple pathogenic viruses. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:4937–55.

Anafu AA, Bowen CH, Chin CR, Brass AL, Holm GH. Interferon-inducible transmembrane protein 3 (IFITM3) restricts reovirus cell entry. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:17261–71.

Li C, Du S, Tian M, Wang Y, Bai J, Tan P, Liu W, Yin R, Wang M, Jiang Y, et al. The host restriction factor interferon-inducible transmembrane protein 3 inhibits vaccinia virus infection. Front Immunol. 2018;9:228.

Compton AA, Bruel T, Porrot F, Mallet A, Sachse M, Euvrard M, Liang C, Casartelli N, Schwartz O. IFITM proteins incorporated into HIV-1 virions impair viral fusion and spread. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16:736–47.

Wrensch F, Karsten CB, Gnirss K, Hoffmann M, Lu K, Takada A, Winkler M, Simmons G, Pohlmann S. Interferon-induced transmembrane protein-mediated inhibition of host cell entry of ebolaviruses. J Infect Dis. 2015;212(Suppl 2):S210-218.

Brass AL, Huang IC, Benita Y, John SP, Krishnan MN, Feeley EM, Ryan BJ, Weyer JL, van der Weyden L, Fikrig E, et al. The IFITM proteins mediate cellular resistance to influenza A H1N1 virus, West Nile virus, and dengue virus. Cell. 2009;139:1243–54.

Bailey CC, Huang IC, Kam C, Farzan M. Ifitm3 limits the severity of acute influenza in mice. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002909.

Savidis G, Perreira JM, Portmann JM, Meraner P, Guo Z, Green S, Brass AL. The IFITMs inhibit Zika virus replication. Cell Rep. 2016;15:2323–30.

Huang IC, Bailey CC, Weyer JL, Radoshitzky SR, Becker MM, Chiang JJ, Brass AL, Ahmed AA, Chi X, Dong L, et al. Distinct patterns of IFITM-mediated restriction of filoviruses, SARS coronavirus, and influenza A virus. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001258.

Majdoul S, Compton AA. Lessons in self-defence: inhibition of virus entry by intrinsic immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22:339–52.

Smith S, Weston S, Kellam P, Marsh M. IFITM proteins-cellular inhibitors of viral entry. Curr Opin Virol. 2014;4:71–7.

Tartour K, Nguyen XN, Appourchaux R, Assil S, Barateau V, Bloyet LM, Burlaud Gaillard J, Confort MP, Escudero-Perez B, Gruffat H, et al. Interference with the production of infectious viral particles and bimodal inhibition of replication are broadly conserved antiviral properties of IFITMs. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006610.

Xie M, Xuan B, Shan J, Pan D, Sun Y, Shan Z, Zhang J, Yu D, Li B, Qian Z. Human cytomegalovirus exploits interferon-induced transmembrane proteins to facilitate morphogenesis of the virion assembly compartment. J Virol. 2015;89:3049–61.

Wee YS, Roundy KM, Weis JJ, Weis JH. Interferon-inducible transmembrane proteins of the innate immune response act as membrane organizers by influencing clathrin and v-ATPase localization and function. Innate Immun. 2012;18:834–45.

Sieczkarski SB, Whittaker GR. Viral entry. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;285:1–23.

Lee WJ, Fu RM, Liang C, Sloan RD. IFITM proteins inhibit HIV-1 protein synthesis. Sci Rep. 2018;8:14551.

Picard-Maureau M, Jarmy G, Berg A, Rethwilm A, Lindemann D. Foamy virus envelope glycoprotein-mediated entry involves a pH-dependent fusion process. J Virol. 2003;77:4722–30.

Life RB, Lee EG, Eastman SW, Linial ML. Mutations in the amino terminus of foamy virus Gag disrupt morphology and infectivity but do not target assembly. J Virol. 2008;82:6109–19.

Yao X, Guo HY, Liu C, Xu X, Du JS, Liang HY, Geng YQ, Qiao WT. A quantitative assay for measuring of bovine immunodeficiency virus using a luciferase-based indicator cell line. Virol Sin. 2010;25:137–44.

Durocher Y, Perret S, Kamen A. High-level and high-throughput recombinant protein production by transient transfection of suspension-growing human 293-EBNA1 cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:E9.

Tai HY, Sun KH, Kung SH, Liu WT. A quantitative assay for measuring human foamy virus using an established indicator cell line. J Virol Methods. 2001;94:155–62.

Smith SE, Busse DC, Binter S, Weston S, Diaz Soria C, Laksono BM, Clare S, Van Nieuwkoop S, Van den Hoogen BG, Clement M, et al. Interferon-induced transmembrane protein 1 restricts replication of viruses that enter cells via the plasma membrane. J Virol. 2019;93:e02003-18.

Narayana SK, Helbig KJ, McCartney EM, Eyre NS, Bull RA, Eltahla A, Lloyd AR, Beard MR. The interferon-induced transmembrane proteins, IFITM1, IFITM2, and IFITM3 inhibit hepatitis C virus entry. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:25946–59.

Materniak-Kornas M, Tan J, Heit-Mondrzyk A, Hotz-Wagenblatt A, Lochelt M. Bovine foamy virus: shared and unique molecular features in vitro and in vivo. Viruses. 2019;11:1084.

Kim J, Shin CG. IFITM proteins inhibit the late step of feline foamy virus replication. Anim Cells Syst (Seoul). 2020;24:282–8.

Ahi YS, Yimer D, Shi G, Majdoul S, Rahman K, Rein A, Compton AA. IFITM3 reduces retroviral envelope abundance and function and is counteracted by glycoGag. MBio. 2020;11:e03088-19.

Lu J, Pan Q, Rong L, He W, Liu SL, Liang C. The IFITM proteins inhibit HIV-1 infection. J Virol. 2011;85:2126–37.

Li K, Markosyan RM, Zheng YM, Golfetto O, Bungart B, Li M, Ding S, He Y, Liang C, Lee JC, et al. IFITM proteins restrict viral membrane hemifusion. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003124.

Marziali F, Cimarelli A. Membrane interference against HIV-1 by intrinsic antiviral factors: the case of IFITMs. Cells. 2021;10:1171.

Dupont A, Gluck IM, Ponti D, Stirnnagel K, Hutter S, Perrotton F, Stanke N, Richter S, Lindemann D, Lamb DC. Identification of an intermediate step in foamy virus fusion. Viruses. 2020;12:1472.

Shi G, Schwartz O, Compton AA. More than meets the I: the diverse antiviral and cellular functions of interferon-induced transmembrane proteins. Retrovirology. 2017;14:53.

Acknowledgements

We thank Maxine L. Linial (Division of Basic Sciences, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA) for sharing the valuable plasmids. We also thank Chen Liang (McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada) for helpful comments and discussion of the paper and for providing the valuable plasmids.

Funding

This research was funded by Grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32070156, 32170149, and 81571988) and the Key International Cooperation Project of the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFE0107600).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZW and XT: performed the experiments, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. These authors contributed equally to this work. JZ: Validation. KC: Investigation. WQ: conceived and designed the study, Funding acquisition and supervised the project. JT: participated in the design and interpretation of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors consent to the publication of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Fig. S1. IFITM3 knockdown in HT1080-shIFITM3 cells was specific. The mRNA levels of IFITM1, IFITM2 and IFITM3 in HT1080-shIFITM3 cells were detected by quantitative PCR. Values were statistically evaluated using a two-way ANOVA. Compared with the HT1080-shNC cells: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Error bars represent the standard deviations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Tuo, X., Zhang, J. et al. Antiviral role of IFITM3 in prototype foamy virus infection. Virol J 19, 195 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-022-01931-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-022-01931-x