Abstract

Background

Most forcibly displaced persons are hosted in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). There is a growing urbanization of forcibly displaced persons, whereby most refugees and nearly half of internally displaced persons live in urban areas. This scoping review assesses the sexual and reproductive health (SRH) needs, outcomes, and priorities among forcibly displaced persons living in urban LMIC.

Methods

Following The Joanna Briggs Institute scoping review methodology we searched eight databases for literature published between 1998 and 2023 on SRH needs among urban refugees in LMIC. SHR was operationalized as any dimension of sexual health (comprehensive sexuality education [CSE]; sexual and gender based violence [GBV]; HIV and STI prevention and control; sexual function and psychosexual counseling) and/or reproductive health (antental, intrapartum, and postnatal care; contraception; fertility care; safe abortion care). Searches included peer-reviewed and grey literature studies across quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods designs.

Findings

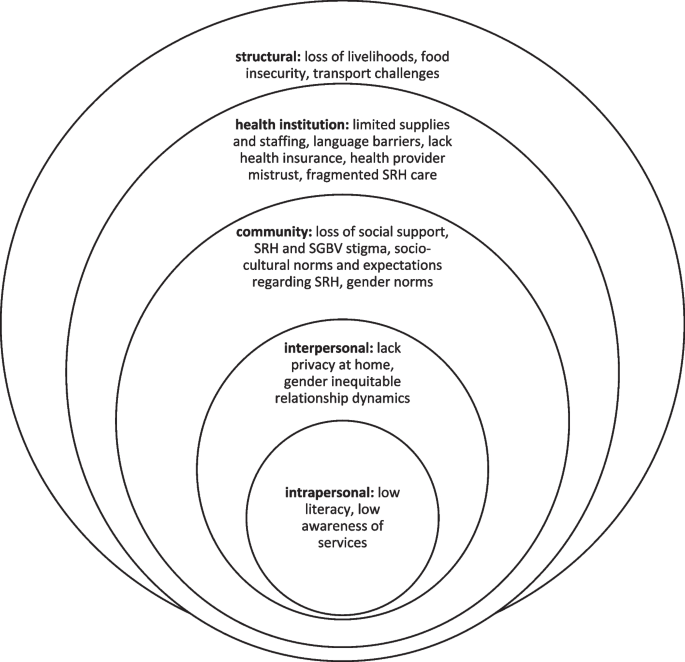

The review included 92 studies spanning 100 countries: 55 peer-reviewed publications and 37 grey literature reports. Most peer-reviewed articles (n = 38) discussed sexual health domains including: GBV (n = 23); HIV/STI (n = 19); and CSE (n = 12). Over one-third (n = 20) discussed reproductive health, including: antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care (n = 13); contraception (n = 13); fertility (n = 1); and safe abortion (n = 1). Eight included both reproductive and sexual health. Most grey literature (n = 29) examined GBV vulnerabilities. Themes across studies revealed social-ecological barriers to realizing optimal SRH and accessing SRH services, including factors spanning structural (e.g., livelihood loss), health institution (e.g., lack of health insurance), community (e.g., reduced social support), interpersonal (e.g., gender inequitable relationships), and intrapersonal (e.g., low literacy) levels.

Conclusions

This review identified displacement processes, resource insecurities, and multiple forms of stigma as factors contributing to poor SRH outcomes, as well as producing SRH access barriers for forcibly displaced individuals in urban LMIC. Findings have implications for mobilizing innovative approaches such as self-care strategies for SRH (e.g., HIV self-testing) to address these gaps. Regions such as Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean are underrepresented in research in this review. Our findings can guide SRH providers, policymakers, and researchers to develop programming to address the diverse SRH needs of urban forcibly displaced persons in LMIC.

Plain English summary

Most forcibly displaced individuals live in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), with a significant number residing in urban areas. This scoping review examines the sexual and reproductive health (SRH) outcomes of forcibly displaced individuals in urban LMICs. We searched eight databases for relevant literature published between 1998 and 2023. Inclusion criteria encompassed peer-reviewed articles and grey literature. SRH was defined to include various dimensions of sexual health (comprehensive sexuality education; sexual and gender-based violence; HIV/ STI prevention; sexual function, and psychosexual counseling) and reproductive health (antenatal, intrapartum, and postnatal care; contraception; fertility care; and safe abortion care). We included 90 documents (53 peer-reviewed articles, 37 grey literature reports) spanning 100 countries. Most peer-reviewed articles addressed sexual health and approximately one-third centered reproductive health. The grey literature primarily explored sexual and gender-based violence vulnerabilities. Identified SRH barriers encompassed challenges across structural (livelihood loss), health institution (lack of insurance), community (reduced social support), interpersonal (gender inequities), and individual (low literacy) levels. Findings underscore gaps in addressing SRH needs among urban refugees in LMICs specifically regarding sexual function, fertility care, and safe abortion, as well as regional knowledge gaps regarding urban refugees in Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. Self-care strategies for SRH (e.g., HIV self-testing, long-acting self-injectable contraception, abortion self-management) hold significant promise to address SRH barriers experienced by urban refugees and warrant further exploration with this population. Urgent research efforts are necessary to bridge these knowledge gaps and develop tailored interventions aimed at supporting urban refugees in LMICs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

As of mid-2022, the global number of forcibly displaced individuals reached an estimate of 103 million [1], a significant majority of this population (53.2 million individuals) are internally displaced [1]. While approximately one-third, totaling 32.5 million people, hold recognized refugee status, another 4.9 million individuals are actively seeking asylum in another country [1, 2]. Forcibly displaced persons may experience poorer sexual and reproductive (SRH) outcomes than non-displaced persons due to the interplay of complex social ecological factors [3]. For instance, forcibly displaced persons may be exposed to sexual and gender-based violence (GBV) before, during, and/or following displacement, and/or upon resettlement. Further, they may experience reduced access to SRH services, including contraception and sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevention and treatment, due to poverty, socio-cultural differences, language, and literacy barriers [4,5,6,7]. Social and structural barriers such as intersectional stigma related to forcibly displaced status, gender, age, and limited SRH literacy can further constrain SRH engagement [8, 9].

Low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) host 74% of the globally forcibly displaced population, and it is estimated that the majority of refugees and nearly half (48%) of internally displaced people live in urban areas [1, 2, 10]. There is the potential that forcibly displaced persons residing in urban settings LMIC may live in poorer housing conditions with less economic and social support than those living in refugee camps or refugee settlement environments managed by humanitarian agencies [11, 12]. For instance, challenges facing forcibly displaced persons living in urban LMIC contexts can include transportation costs, higher living costs that may result in overcrowded living conditions, poverty, and language barriers to accessing relevant employment, education, health and other services [13,14,15]. It is plausible that these factors can also reduce the accessibility and utilization of SRH services. Inadequate SRH service provision is associated with increased gender-based violence (GBV), elevated risks for acquisition and transmission of HIV and other STIs, unintended pregnancies, and unsafe abortions [8, 16]. Further, urbanization among refugees may contribute to poverty and exacerbate gender inequities, both associated with increased likelihood of GBV [3, 17, 18]. With rising urbanization among forcibly displaced persons, there is a need for greater understanding of the sexual and reproductive health (SRH) outcomes and priorities to inform tailored intervention and programs.

Existing systematic reviews have reported evidence-based approaches to improve antenatal, postnatal, and newborn health, HIV prevention and treatment outcomes, and uptake of family planning resources and services, for forcibly displaced persons at large [19, 20]. There is evidence that interpersonal, health-system, and socio-cultural factors shape access to SRH care among forcibly displaced peoples [21]. Literature has also documented relationships between climate migration and GBV, decreased maternal and neonatal health, and increased barriers to accessing and using SRH services [22]. While these important reviews document factors that shape SRH among forcibly displaced peoples at large, there remains a notable lack of research focused on forcibly displaced persons regarding SRH issues including GBV prevention, STI transmission and treatment, menstruation hygiene management, and disrupted access to SRH care [19, 22]. Further, findings have not distinguished between urban or refugee camp/settlement contexts, resulting in a lack of clarity regarding specific needs, priorites, and SRH outcomes among forcibly displaced persons in urban LMIC contexts.

The objective of this scoping review is to identify, critically appraise, and synthesize the literature on sexual and reproductive health needs, outcomes, and priorities of forcibly displaced persons living in urban LMICs. A comprehensive understanding of these dimensions and existing research gaps can inform future practice, research, and policy.

Methods

The Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for scoping reviews was followed throughout this review [23]. A complete and comprehensive explanation of the methods used can be found in the published study protocol [24].

Search strategy

Completed in January 2023, we searched eight databases, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, IBSS, ASSIA, SSCI, and Global Medicus Index, for literature published between 1998 and 2022 on SRH needs among forcibly displaced persons in LMIC. The search structure first grouped terms for each of urban, refugees, sexual health, low and middle-income countries, and reproductive health using the Boolean operator OR. Following this, terms for urban and refugees were combined using the Boolean operator AND, and terms for sexual health and reproductive health were combined using the Boolean operator OR. Lastly, the search terms for urban refugees, sexual health or reproductive health, and low and middle-income countries were combined using the Boolean operator AND – ((urban OR cities OR municipal) AND (refugee* OR displace* OR asylum)) AND ((sexual health OR gender-based violence OR sexually transmitted disease*) OR (reproductive health OR prenatal OR contraception)) AND (low income countries OR middle income countries OR developing nations). A detailed search strategy for all databases can be found in the Supplementary File 1. A grey literature search was also conducted in accordance with a search guide developed by Godin et al. [25].

Study selection

The study population was a) any forcibly displaced person, following UNHCR’s definition that includes refugee, migrant, asylum seeker, or internally displaced persons forced to flee due to persecution, conflict, human rights violations, or other serious events disrupting order [1, 2], b) living in a LMIC as defined by the World Bank Atlas Method [26] and c) living in an urban context, including urban, semi-urban, city, metropolis, or if study location is listed as urban in the UN World Urbanization Prospects database of country-specific definitions of ‘urban’ [27]. SRH was operationalized as any dimension of sexual health (comprehensive sexuality education [CSE]; sexual and gender based violence [GBV]; HIV and STI prevention and control; sexual function and psychosexual counseling) and/or reproductive health (antental, intrapartum, and postnatal care; contraception counselling and provision; fertility care; safe abortion care) [28, 29].

We included peer-reviewed or gray literature studies using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods designs focused on any dimension of sexual/reproductive health written in the English language. Studies were excluded if they a) did not include forcibly displaced persons; b) included migrants by choice; c) did not focus on SRH; d) were not based in urban contexts; e) had metadata not in English; and f) there was no full-text article available. Key subject terms were searched among websites of governmental, non-governmental, and international organizations working with forcibly displaced persons.

Data extraction and analysis

Once both the database search and grey literature search were completed, data from included records were extracted by a reviewer into a spreadsheet. All records were uploaded on to Covidence systematic review software (VeritasHealth Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) and duplicates were removed. On Covidence, each record’s title and abstract were screened by at least 2 study team members for inclusion eligibility. The full texts of all included articles were further screened by two study team members. At this point, the reference list of each included article was manually hand searched. If a relevant article was found via hand search, it was entered into Covidence and put through the screening process as outlined. All discrepancies were reviewed by a third team member and/or discussed with all reviewers. Extracted data points included the record’s general characteristics, population, concept, context, main outcome measure, and key findings relevant to this review. Every record’s data extraction was examined by a second team member for accuracy. All data were then summarized and collated into the accompanying narrative summaries.

Results

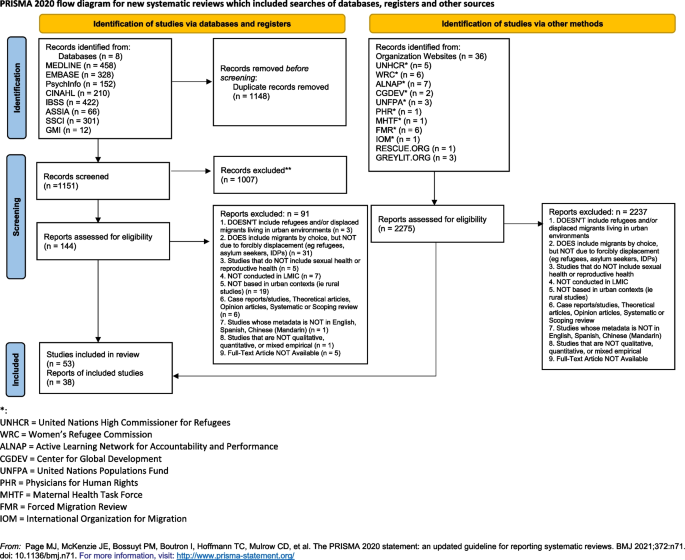

Our peer-reviewed article search returned 1151 results across eight databases and 2275 grey literature reports. In total, 92 documents including 55 peer-reviewed articles and 37 grey literature pieces met the inclusion criteria for this scoping review. Among the peer-reviewed articles, PRISMA Flow Chart in Fig. 1 shows the selection process for 53 peer-reveiewed articles (Fig. 1). Six additional peer-reviewed articles were hand searched, 2 of which met the inclusion criteria and were included.

The peer-reviewed articles were mapped onto dimensions of sexual health and reproductive health [29] (Table 1). The majority of peer-reviewed articles (n = 40; 72.7%) discussed sexual health domains including: GBV prevention, support and care (n = 23); HIV and STI prevention and control (n = 21); and comprehensive sexuality education (n = 12). Under the sexual health domain, no articles were located that discussed sexual function and psychosexual counselling. More than one-third (n = 20; 36.3%) discussed reproductive health areas including: antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care (n = 13); contraception counselling & provision (n = 13); fertility care (n = 1); and safe abortion care (n = 1). While not within the SRH framework [28, 29], menstrual hygiene management was included as a SRH issue in this review as it was discussed in three articles. Eight articles discussed intervention areas that included both reproductive and sexual health domains. Sexual and reproductive health dimensions covered in peer-reviewed articles are displayed in Table 2.

Sexual and gender-based violence (GBV)

Among the 17 studies that examined GBV [32, 33, 36, 37, 40,41,42, 45, 46, 52, 61, 68, 69, 73,74,75,76] in urban contexts, all explored GBV as it was experienced by women and girls, and one examined experiences of both adolescent boys and girls [52]. Most articles explored experiences of adult women: two explored GBV among adolescent girls [75, 76] and one explored GBV experiences among young women [68].

Prevalence and health correlates of intimate partner violence

Of the 17 articles that examined GBV, most (n = 11; 64.7%) specifically examined intimate partner violence (IPV) [32, 33, 40,41,42, 45, 52, 61, 69, 73, 76]. Prevalence ranged from 11.1%-86.0% and varied by age, type of IPV, and external factors. All studies examined the experience of adults, with the exception of two that looked at adolescents, and these found the highest prevalences of IPV at 85.8% and 86.0% [52, 76]. Two articles examined the prevalence of different types of IPV. One study found partner control followed by economic abuse and emotional abuse to be the most common forms of IPV at 73%, 53.3%, and 50.3% respectively [33]. Another study found slapping and throwing objects to be the most common forms of physical IPV [41].

More than half of these articles reported associations between IPV and health and wellbeing (n = 6), incuding mental, physical, and other SRH outcomes. For instance, there were associations between experiencing IPV and mental health concerns such as post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms [61] and frequent alcohol use [52]. One study with refugee women in Amman, Irbid and Zarqa, Jordan found an association between psychological IPV and higher rates of health problems including heart, gastrointestinal, liver, respiratory, and urinary problems, recurrent dizziness, fibromyalgia, joint pain, and back pain [32]. Another study with refugee women in Semnan, Iran found IPV exposure was associated with a range of SRH outcomes, including early marriage, sexual coercion, unwanted pregnancy, and a high number of children [40].

The different ways that IPV was measured across studies make it difficult to synthesize these findings, however across studies it appears that a) urban forcibly displaced girls and women are disproportionately exposed to polvictimization (multiple forms of violence); b) there is a range of health challenges linked with IPV exposure, including and extending beyond SRH; and c) married women reported a high prevalence of IPV, including during pregnancy.

Risk factors associated with GBV exposure

Seven of the 17 articles that examined GBV explored risks associated with GBV exposure (41.2%) [36, 37, 42, 46, 52, 68, 75]. Three studies collected data from women only [36, 42, 46] while the other four collected data from both women and men [37, 52, 68, 75]. One study found that women were more likely to share stories about sexual harassment while men more likely to discuss other forms of GBV [68].

GBV exposure risks varied across social categories, including age, education, changing social structures and norms, and disruption to social networks and livelihoods. For instance, studies with adolescent girls and young women, including refugees in Beirut, Beqaa, and Tripoli, Lebanon [68] and displaced people in Izmir, Turkey [75], reported that early marriage was associated with risks for further GBV [68, 75]. Among those experiencing early marriage, factors that increased risks for GBV included limited educational opportunities, financial strains, and being alone outside the home [75]. Further, urbanization may change parents’ perspectives on child marriage after arriving in Lebanon, as they may be more likely to view early marriage as a pathway to protecting their daughters and reducing parental responsibility [39].

Among internally displaced adult women, displacement and subsequent loss of social support networks elevated risks for GBV [36, 37]. For instance, in a study conducted in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, destruction of livelihood elevated risks for GBV [36]. Findings paralleled another study in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire that documented that poverty, food and housing instability, and changing gender roles and norms increased GBV exposure [37]. Partner characteristics and relationship dynamics were also associated with GBV, including partner alcohol misuse [41, 42]. Among pregnant refugees in Sidon, Lebanon, odds of IPV were higher among those whose husbands did not want the pregnancy [42].

Polyvictimization was also reported [73, 74, 76]. For instance, forcibly displaced women with a history of childhood abuse may be more likely to experience adulthood violence [76], and as adult, forcibly displaced women may report multiple forms (e.g., physical violence, abductions, forced imprisonment, sexual violence, early/forced marriage) and contexts of violence (country of origin, host country) [74]. Together these studies on GBV suggest that multi-level factors, including structural (poverty, livelihood and educational barriers), social (gender inequitable norms, disrupted social networks), and relational (relationship power dynamics, partner alcohol use) level factors increase vulnerability to multiple forms of GBV among urban forcibly displaced persons.

HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

Among the 20 articles examining HIV and STIs, 17 focused only on HIV, one article focused on HIV and transactional sex [50], one on STIs [49], and one on both HIV and STIs [54].

HIV and STI testing and prevention

Half of the HIV/STI articles focused on HIV testing and prevention (n = 10, 50%) [13, 44, 47, 50, 51, 53, 56, 70, 71, 77]. Most of these were quantitative (n = 7) with three qualitative studies. Studies explored experiences among urban forcibly displaced men and women in Uganda [13, 47, 50, 51, 53, 77], Nepal [44], and Peru [56], and refugee men who have sex with men (MSM) in Lebanon [70, 71]. Testing uptake, recorded in six studies, ranged from 29–62% and varied by gender and population [44, 47, 50, 70, 71, 77]. For instance, a study with refugees engaged in transactional sex in Kampala, Uganda found that engaging in transactional sex was associated with lower HIV testing among men, and was not associated with HIV testing among women [50].

Among articles that examined HIV testing [13, 44, 47, 51, 53, 56], transportation costs, overcrowded living conditions, low literacy, and inequitable gender norms were identified as testing barriers [13, 53]. Intersecting stigma—including stigma related to HIV, refugees, sexually active adolescents, and sex workers—also presented barriers to HIV testing among urban refugee youth in Kampala, Uganda [44, 47, 51]. Among urban Venezuelan forcibly displaced women in 6 cities in Peru (Metropolitan Lima, Callao, Tumbes, Cusco, Trujillo, Arequipa), not having health insurance was a barrier to HIV and STI testing [56]. Among MSM in Beirut, Lebanon, lack of comfort with doctors, not seeing a doctor in the past year, and not knowing where to access testing posed as barriers to testing [70, 71] Among forcibly displaced urban refugee youth in Kampala, Uganda, factors associated with STI testing were lower food insecurity and lower adolescent SRH stigma [49].

Several studies focused on HIV vulnerabilities among forcibly displaced persons in urban Uganda [52, 66, 78]. For instance, a study in Gulu with internally displaced men and women reported an HIV prevalence of 12.8%, and risk factors associated with HIV infection included non-consensual sexual debut, past-year STI symptoms, and practicing dry sex (which was defined as sexual intercourse without foreplay or lubrication so that the vagina is dry upon penetration) [66]. Another study in Kampala, Uganda with refugee youth found that depression, alcohol use, and GBV were associated with HIV vulnerabilities, including recent transactional sex and multiple sex partners [52]. There may also be gender differences in HIV vulnerabilities; among urban refugee adolescents in Kampala, Uganda, young men reported higher condom self-efficacy than young women [62, 63]. A study in Beirut, Lebanon found that over half (56.7%) of refugee MSM reported unprotected anal intercourse with men who were HIV positive or did not know their HIV serostatus, and over a third (36%) had engaged in transactional sex [70, 71]. A qualitative study with internally displaced women in Northern Uganda found that the shift away from traditional belief systems, collapse of livelihoods, commuting away from home at night, and inadequate access to SRH information and services elevated HIV vulnerabilities among adolescent girls [78]. Another qualitative study, with forcibly displaced adult women in Medellin, Colombia, found that social and family fragmentation, GBV, abrupt changes in daily lives, and inequitable gender norms elevated HIV and STI acquisition risks [54]. These studies taken together reveal the ways that conflict-related life disruptions (e.g., belief systems, livelihoods, social networks), alongside structural factors (e.g., gender inequities, SGBV across the lifecourse, barriers to accessing SRH services) and relational factors (e.g., sexual practices, low condom efficacy), may increase exposure to HIV and STIs and reduce access to testing.

HIV treatment and care

Four articles focused on antiretroviral therapy (ART) and HIV care among urban refugee adult men and women [58,59,60, 64]. Two quantitative studies in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia that compared HIV treatment and clinical outcomes between refugees, displaced people, asylum seekers, and host community members found no differences in viral suppression among groups [58, 59]. Qualitative studies explored challenges associated with achieving optimal treatment adherence [60, 64]. One of these studies that included forcibly displaced persons in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia found that limited access to food, pharmacy stock-outs, and difficulty navigating a new health system were barriers to optimal treatment adherence [60]. The few studies on HIV treatment and care that were included in this review span wide-ranging contexts, presenting challenges in drawing conclusions from this evidence-base and signal the need for more research with urban forcibly displaced persons living with HIV.

Antenatal care, postnatal care, and contraception

Among the 13 articles that explored antenatal and postnatal care and contraception, six focused on antenatal and postnatal care (46.2%) [30, 34, 35, 38, 65, 72] and seven on contraception and family planning (53.8%) [31, 43, 55, 56, 62, 63, 67]. Most of these studies were conducted with adult forcibly displaced women (n = 9); one was conducted with healthcare workers and policy makers alongside adult women [34]. The remaining three studies were conducted with forcibly displaced adolescents, one of which explored experiences of only women [55].

Antenatal and postnatal care

Two of the 13 articles that examined antenatal and postnatal care used quantitative methods to explore uptake of antenatal care [30, 35]. One study found that 82.9% of pregnant refugees had received some antenatal care in 14 high refugee density sites, including Beirut, in Lebanon [35], while another study found that pregnant refugees in Tehran, Iran attended an average of 3.73 out of 8 possible antenatal appointments [30]. Four articles explored barriers to accessing care and related risks [34, 38, 65, 72]. One of these studies with pregnant refugees in South Tehran, Iran found that financial constraints, lack of health insurance, transportation challenges, stigma, cultural concerns, legal and immigration issues, and healthcare staff behaviour presented barriers to utilizing prenatal services [38]. Moreover, an article with pregnant forced migrant mothers in Mumbai, India reported that they could not access the antenatal care they need due to unfamiliarity with the local context and a lack of knowledge regarding where to access antenatal care, putting them at a greater risk for poor health outcomes [65]. From these limited studies, structural level challenges (e.g., health insurance barriers, healthcare mistreatment, immigration issues) alongside socio-cultural challenges (e.g., stigma, cultural and religious concerns) posed barriers to antenatal and postnatal care.

Contraception

Among the seven articles that explored family planning, five used quantitative methods to explore the access and utilization of contraceptives [55, 56, 62, 63, 67]. One study found that only 20.2% of migrant and refugee women in six urban cities in Peru had access to modern contraceptives [56]. Contraceptive access was reported to be influenced by family and relationship status as well as dynamics. For instance, among migrant and refugee women in six urban sites in Peru, lower socio-economic status was associated with reduced likelihood of emergency contraceptive use, and those who were married or lived with a partner were more likely to use modern and emergency contraceptives [56]. A qualitative study with forcibly displaced women in West Bekaa, Lebanon described that beliefs about wanting a large family size were often in tension with the financial hardships they experienced in displacement, men held the dominant role in making decisions about family planning, and contraceptive access was hindered by the unaffordability of the privatised health system [43]. Another qualitative study found that internally displaced women in Maputo, Mozambique experienced social isolation excluding them from the contraceptive revolution in their host community [31]. Together these studies paint a complex picture of contraceptive access and needs, where some factors associated with low contraception uptake may include structural barriers (e.g., low socio-economic status), relational factors, (e.g., relationship status), and socio-cultural values and priorities (e.g., wishes for larger family sizes) shaped by community norms and experiences of conflict.

Grey literature findings

Among the 37 included grey literature reports, over three-quarters (n = 29) examined GBV [79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108]; these studies are detailed in Table 3. Emergent GBV themes centered on vulnerabilities to experiencing sexual, physical, and psychological abuse. Reports describe forcibly displaced persons in urban humanitarian contexts were at elevated risk for GBV exposure due to various social, cultural, and political dynamics, such as income insecurity, overcrowded living conditions, inequitable gender dynamics, inequitable power dynamics with administrative authorities, and limited awareness of rights [86, 88, 90,91,92,93,94, 97, 101, 104, 105, 108]. Perpetrators of GBV included landlords, neighbors and employers, all of whom displaced people may be dependent on, and in lower positions of power [104, 105]. The main reported targets of violence were women, sexual minorities, and transgender people [83, 85,86,87, 94,95,96, 100, 107, 108]. These reports, taken together, emphasize the importance of integrated policies, research, and SRH services to reduce GBV and promote health equity among individuals at risk, including sexually and gender diverse persons. Additionally, the reports emphasize the critical need for support services to aid GBV survivors [79, 82, 85, 98, 103].

Other themes identified from the grey literature include sex work, disability, contraception needs, and the needs of people living with HIV. Two reports addressed sex work among displaced people who may fear social and legal consequences (including stigma and prosecution) if their sex work was disclosed; accordingly, mobile clinics were suggested as an appropriate entry point for SRH services tailored for forcibly displaced sex workers [80, 109]. Another report described barriers to accessing SRH services, including HIV/STI testing and family planning, for forcibly displaced persons with disabilities, noting stigma faced by forcibly displaced people with disabilities [106]. Multiple studies described SRH service gaps, notably a lack of choice regarding a variety of family planning methods for forcibly displaced women, and limited access to HIV care for forcibly displaced people living with HIV [113, 115, 116]. Recommendations for improving access to SRH services for urban forcibly displaced people included: (1) improved collaboration between various systems and authorities that forcibly displaced people interface with; (2) wider dissemination of SRH knowledge to forcibly displaced persons; (3) the need to create safe, inclusive, and culturally-aware SRH spaces; and (4) the importance of empowering women and girls in humanitarian contexts to mitigate gender inequity as a barrier to SRH access [110,111,112, 114].

Discussion

Findings from this scoping review underscore that forcibly displaced individuals in urban LMIC settings face multiple barriers to SRH. These barriers encompass structural (e.g., loss of livelihoods, lack of health insurance), social (e.g., limited access to community support), interpersonal (e.g., gender inequitable relationship dynamics), and intrapersonal (e.g., poor mental health) factors. These barriers align with a social ecological [117, 118] approach to health that accounts for the complex interplay between different spheres of influence, and can inform tailored interventions that target one or more levels for change (see Fig. 2). Our findings also identify understudied sexual health (i.e., sexual function and psychosexual counseling) and reproductive health (i.e., fertility care, safe abortion care) domains with this population.

We found across included studies that displacement processes were discussed as exacerbating SRH vulnerabilities among forcibly displaced persons in urban LMIC settings [31, 36, 37, 54, 57, 60, 65, 78]. These included the role of displacement in the breakdown of social support networks and loss of livelihoods in increasing exposure to GBV while also reducing access to sexual health services such as HIV/STI testing. However, the paucity of studies precludes synthesizing experiences by SRH domain (e.g., safe abortion), setting (e.g., slums/informal settlement), or population (e.g., adolescent). A similar limitation was identified by Singh et al. in their 2018 systematic review on the utilization of SRH services in humanitarian crises at large [119]. This observation signals a persistent lack of substantial progress in advancing the field as a whole, and in turn the contextually specific needs of urban forcibly displaced persons. We also found a limited focus on safe abortion and STIs beyond HIV. This suggests a need for additional attention to these understudied SRH issues.

Our findings indicate that stigma experienced by urban forcibly displaced persons presents barriers to SRH prevention, access, and care. Stigma is intersectional, targeting various identities such as refugee status and gender and spans across social-ecological levels, including being manifested at structural (e.g., laws and policies), health institution (e.g., healthcare mistreatment), community (e.g., stigma toward refugees), interpersonal (e.g. gender-based stigma), and intrapersonal (e.g., self-stigma) levels. Moreover, stigma is rooted in drivers and facilitators that could be effectively addressed through targeted stigma-reduction interventions [120]. Stigma within healthcare facilities can reinforce a wider mistrust of health systems among refugee and displaced persons [17, 51]. There is scarcity of SRH interventions focused on stigma reduction with this population.

We documented that resource scarcities (e.g., food, housing, economic) were associated with worse SRH outcomes among urban forcibly displaced persons [37, 60, 75, 76]. This reflects the long-standing insufficient funding and resources for SRH (and health care more generally) in humanitarian settings [48]. Once a forcibly displaced person leaves a formal refugee settlement/camp to migrate to urban regions, many forgo formal financial support offered by UNHCR or other refugee settlement-based organizations to refugees living in settlements, such as food, land/housing, or economic stipends. They may then experience financial challenges, such as transportation costs to accessing healthcare, high rent in cities and/or substandard housing in urban informal settlements, in addition to lack of health insurance in some contexts. These resource scarcity barriers to SRH care are further exacerbated by individual-level barriers such as low literacy and language barriers, and systemic-level barriers such as insufficient staffing and medication stock-outs.

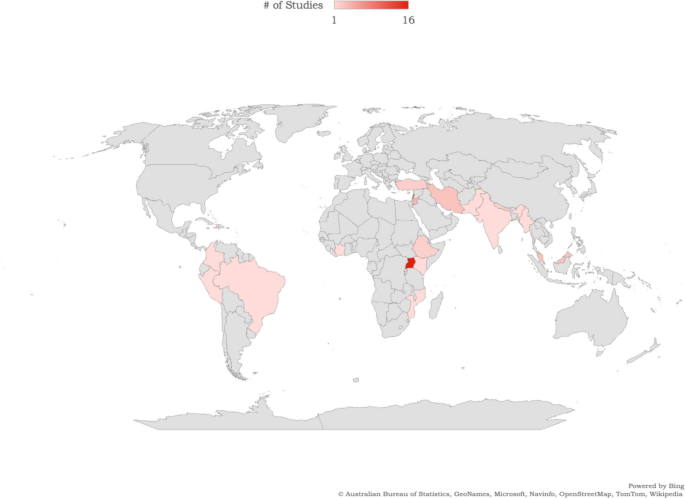

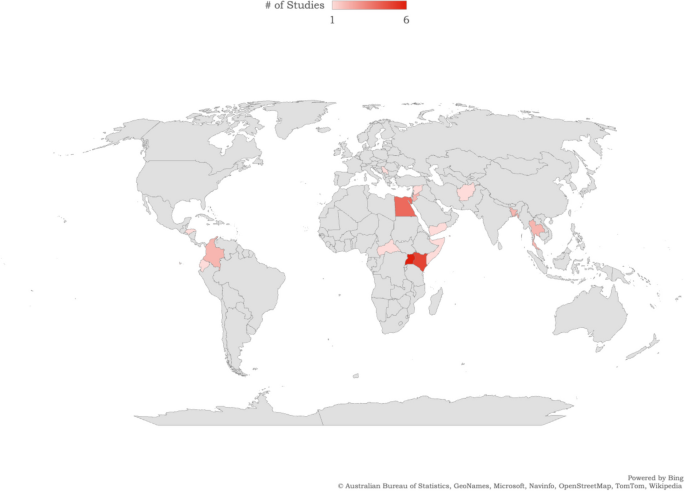

Our study has limitations. We focused on a select range of SRH outcomes as defined by a SRH conceptual framework [28, 29] and may have overlooked other important issues relevant to SRH outside of this (e.g., fistulae). Our criteria for language inclusion may have omitted some relevant articles. As there was so many different contexts, article types, refugee types (e.g., displaced, refugee), and populations (e.g., adolescents, pregnant adult women), we could not conduct a meta-analysis, and even when synthesizing key findings this heterogeneity presented challenges in contextualizing SRH findings within each setting and its socio-cultural norms, geography, country income, and laws and other social determinants of health. It is plausible that urban refugees may share health status outcomes with host communities while living in urban informal settlements or slums due to the nature of shared socio-cultural and economic conditions in slums [121], yet these similarities and/or differences in SRH outcomes with host communities were beyond the scope of this review. Further, the studies included in our analysis exhibited a significant underrepresentation of large global regions, namely Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. This limited inclusion of studies from these regions hampers our understanding of the specific needs and priorities of urban forcibly displaced persons residing in these urban contexts (Figs. 3 and 4). Despite these limitations, this review’s strengths include its unique focus on urban forcibly displaced persons in LMIC contexts, where the majority of forcibly displaced persons live. Our review also reinforces the need to include multiply marginalized communities in future SRH research—including urban forcibly displaced sex workers, people who use drugs, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons [122,123,124].

Map of countries of included peer-reviewed studies in this scoping review of urban forcibly displaced persons' sexual and reproductive health in low and middle-income countries. Included countries are represented with colours reflecting the number of studies from each country reported in the figure legend

Map of countries of included grey literature studies in this scoping review of urban forcibly displaced persons' sexual and reproductive health in low and middle-income countries. Included countries are represented with colours reflecting the number of studies from each country reported in the figure legend

Urgent research and interventions are needed to address SRH challenges faced by urban forcibly displaced persons; these strategies can ultimately advance health equity and well-being not only for forcibly displaced persons, but in the case of those living in slums, interventions may have multiplier effects [121]. Future research can identify targets for stigma reduction (e.g., healthcare workers, refugee women) and implement evidence-based intersectional stigma reduction strategies to mitigate barriers to accessing SRH care [125]. Effectively advancing SRH in humanitarian settings requires resources for implementing and evaluating multi-level interventions integrated within existing health systems, as well as community-level, family-level, and individual-level approaches. Such interventions can specifically address health literacy and language needs of urban forcibly displaced persons, transportation-related challenges (e.g., via mobile clinics), and, when needed, extend health insurance coverage to forcibly displaced individuals. Additionally, innovative approaches such as self-care strategies for SRH (e.g., HIV self-testing, long-acting self-injectable contraception, over-the-counter oral contraception, abortion self-management) hold significant promise in addressing some of these aforementioned SRH barriers and can be explored and tested with urban forcibly displaced persons. These self-care strategies may help to overcome challenges related to privacy, transportation, and healthcare provider mistrust [48, 126], yet they also require an enabling social and health environment, so can be offered in tandem with strategies focused on advancing social and health equity [126].

Conclusion

This review identified barriers to SRH care spanning social-ecological levels [117, 118] among urban forcibly displaced persons in LMIC contexts. The process of displacement, resource insecurity, and stigma exacerbate and drive SRH vulnerabilities for urban forcibly displaced persons in LMIC contexts. However, there remain critical knowledge gaps regarding a range of SRH issues across diverse LMIC settings, with particular knowledge gaps regarding socially marginalized populations. Our findings signal that in urban LMIC settings, there may be unique barriers to accessing SRH information, resources and care faced by forcibly displaced persons (e.g., no financial support from UNHCR or other refugee agencies, social isolation, language barriers at clinics) compared to formal refugee settlements where persons may have more access to refugee communities, translators at clinics, and financial stipends (e.g., housing, land, food supplements). Future research and action are required to address the unique and often unmet SRH needs among urban forcibly displaced persons to advance health and rights.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

UNHCR. Refugee Population Statistics Database. UNHCR. [cited 2023 Jan 17]. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/

UNHCR. Global Trends Forced Displacement in 2021. 2021. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/publications/brochures/62a9d1494/global-trends-report-2021.html

Freedman J, Crankshaw TL, Mutambara VM. Sexual and reproductive health of asylum seeking and refugee women in South Africa: understanding the determinants of vulnerability. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2023 Jan 16];28. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7888032/

Ivanova O, Rai M, Mlahagwa W, Tumuhairwe J, Bakuli A, Nyakato VN, et al. A cross-sectional mixed-methods study of sexual and reproductive health knowledge, experiences and access to services among refugee adolescent girls in the Nakivale refugee settlement. Reprod Health. 2019;16:35.

Mwenyango H. Gendered dimensions of health in refugee situations: An examination of sexual and gender-based violence faced by refugee women in Nakivale refugee settlement, Uganda. International Social Work. 2021;00208728211003973.

Iyakaremye I, Mukagatare C. Forced migration and sexual abuse: experience of Congolese adolescent girls in Kigeme refugee camp, Rwanda. Health Psychol Rep. 2016;4:261–71.

Muñoz Martínez R, Fernández Casanueva C, González O, Morales Miranda S, Brouwer KC. Struggling bodies at the border: migration, violence and HIV vulnerability in the Mexico/Guatemala border region. Anthropol Med. 2020;27:363–79.

Ivanova O, Rai M, Kemigisha E. A Systematic Review of Sexual and Reproductive Health Knowledge, Experiences and Access to Services among Refugee, Migrant and Displaced Girls and Young Women in Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:1583.

Dahab M, Spiegel PB, Njogu PM, Schilperoord M. Changes in HIV-related behaviours, knowledge and testing among refugees and surrounding national populations: A multicountry study. AIDS Care. 2013;25:998–1009.

Rees M. Foreword: Time for cities to take centre stage on forced migration. Forced Migration Review. 2020;4–5.

Saliba S, Silver I. Cities as partners: the case of Kampala. Forced Migr Rev. 2020. Available from: https://www.fmreview.org/cities/saliba-silver.

Saghir J, Santoro J. Urbanization in Sub-Saharan Africa. 2018. Available from: https://www.csis.org/analysis/urbanization-sub-saharan-africa

Logie CH, Okumu M, Kibuuka Musoke D, Hakiza R, Mwima S, Kacholia V, et al. The role of context in shaping HIV testing and prevention engagement among urban refugee and displaced adolescents and youth in Kampala, Uganda: findings from a qualitative study. Trop Med Int Health. 2021;26:572–81.

Nara R, Banura A, Foster AM. A Multi-Methods Qualitative Study of the Delivery Care Experiences of Congolese Refugees in Uganda. Matern Child Health J. 2020;24:1073–82.

Suphanchaimat R, Sinam P, Phaiyarom M, Pudpong N, Julchoo S, Kunpeuk W, et al. A cross sectional study of unmet need for health services amongst urban refugees and asylum seekers in Thailand in comparison with Thai population, 2019. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2020;19:205.

Desrosiers A, Betancourt T, Kergoat Y, Servilli C, Say L, Kobeissi L. A systematic review of sexual and reproductive health interventions for young people in humanitarian and lower-and-middle-income country settings. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:666.

Patel RB, Burkle FM. Rapid Urbanization and the Growing Threat of Violence and Conflict: A 21st Century Crisis. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2012;27:194–7.

Korri R, Hess S, Froeschl G, Ivanova O. Sexual and reproductive health of Syrian refugee adolescent girls: a qualitative study using focus group discussions in an urban setting in Lebanon. Reprod Health. 2021;18:130.

Singh NS, Smith J, Aryasinghe S, Khosla R, Say L, Blanchet K. Evaluating the effectiveness of sexual and reproductive health services during humanitarian crises: A systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2018;13: e0199300.

Singh NS, Aryasinghe S, Smith J, Khosla R, Say L, Blanchet K. A long way to go: a systematic review to assess the utilisation of sexual and reproductive health services during humanitarian crises. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3: e000682.

Davidson N, Hammarberg K, Romero L, Fisher J. Access to preventive sexual and reproductive health care for women from refugee-like backgrounds: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:403.

van Daalen KR, Dada S, Issa R, Chowdhury M, Jung L, Singh L, et al. A Scoping Review to Assess Sexual and Reproductive Health Outcomes, Challenges and Recommendations in the Context of Climate Migration. Front Glob Women's Health [Internet]. 2021;2. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2021.757153.

Chapter 11: Scoping reviews - JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis - JBI Global Wiki. [cited 2023 Jan 23]. Available from: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/4687342/Chapter+11%3A+Scoping+reviews

Logie CH, Gittings L, Zhao M, Koomson N, Lorimer N, Qiao C, et al. Sexual and reproductive health outcomes for forcibly displaced persons living in urban environments in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review protocol. JBI Evid Synth. 2022;20:2543–51.

Godin K, Stapleton J, Kirkpatrick SI, Hanning RM, Leatherdale ST. Applying systematic review search methods to the grey literature: a case study examining guidelines for school-based breakfast programs in Canada. Syst Rev. 2015;4:138.

World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

United Nations. World population prospects 2019. 2019. Report No.: 9789211483161. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12283219

Stephenson R, Gonsalves L, Askew I, Say L. Detangling and detailing sexual health in the SDG era. The Lancet. 2017;390:1014–5.

WHO. Sexual health and its linkages to reproductive health: an operational approach. WHO; 2017. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/978924151288

Abbasi-Kangevari M, Amin K, Kolahi A-A. Antenatal care utilisation among Syrian refugees in Tehran: A respondent driven sampling method. Women and Birth. 2020;33:e117–21.

Agadjanian V. Trapped on the Margins: Social Characteristics, Economic Conditions, and Reproductive Behaviour of Internally Displaced Women in Urban Mozambique. J Refug Stud. 1998;11:284–303.

Al-Modallal H. Effect of intimate partner violence on health of women of Palestinian origin. Int Nurs Rev. 2016;63:259–66.

Al-Modallal H, Abu Zayed I, Abujilban S, Shehab T, Atoum M. Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence Among Women Visiting Health Care Centers in Palestine Refugee Camps in Jordan. Health Care Women Int. 2015;36:137–48.

Bahamondes L, Makuch MY, Margatho D, Charles CM, Brasil C, de Amorin HS. Assessment of the availability of sexual and reproductive healthcare for Venezuelan migrant women during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic at the north-western border of Brazil-Venezuela. J Migr Health. 2022;5: 100092.

Benage M, Greenough PG, Vinck P, Omeira N, Pham P. An assessment of antenatal care among Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Confl Health. 2015;9:8.

Campbell DW, Campbell JC, Yarandi HN, O’Connor AL, Dollar E, Killion C, et al. Violence and abuse of internally displaced women survivors of the 2010 Haiti earthquake. Int J Public Health. 2016;61:981–92.

Cardoso LF, Gupta J, Shuman S, Cole H, Kpebo D, Falb KL. What Factors Contribute to Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in Urban, Conflict-Affected Settings? Qualitative Findings from Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. J Urban Health. 2016;93:364–78.

Dadras O, Taghizade Z, Dadras F, Alizade L, Seyedalinaghi S, Ono-Kihara M, et al. “It is good, but I can’t afford it …” potential barriers to adequate prenatal care among Afghan women in Iran: a qualitative study in South Tehran. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:274.

DeJong J, Sbeity F, Schlecht J, Harfouche M, Yamout R, Fouad FM, et al. Young lives disrupted: gender and well-being among adolescent Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Confl Health. 2017;11:23.

Delkhosh M, Merghati Khoei E, Ardalan A, Rahimi Foroushani A, Gharavi MB. Prevalence of intimate partner violence and reproductive health outcomes among Afghan refugee women in Iran. Health Care Women Int. 2019;40:213–37.

Feseha G, G/Mariam A, Gerbaba M. Intimate partner physical violence among women in Shimelba refugee camp, northern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:125.

Hammoury N, Khawaja M, Mahfoud Z, Afifi R a., Madi H. Domestic Violence against Women during Pregnancy: The Case of Palestinian Refugees Attending an Antenatal Clinic in Lebanon. Journal of Women’s Health. 2009;18:337–45.

Kabakian-Khasholian T, Mourtada R, Bashour H, Kak FE, Zurayk H. Perspectives of displaced Syrian women and service providers on fertility behaviour and available services in West Bekaa, Lebanon. Reproductive Health Matters. 2017;25:75–86.

Khatoon S, Budhathoki SS, Bam K, Thapa R, Bhatt LP, Basnet B, et al. Socio-demographic characteristics and the utilization of HIV testing and counselling services among the key populations at the Bhutanese Refugees Camps in Eastern Nepal. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:535.

Khawaja M, Barazi R. Prevalence of wife beating in Jordanian refugee camps: reports by men and women. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:840–1.

Khawaja M, Hammoury N. Coerced Sexual Intercourse Within Marriage: A Clinic-Based Study of Pregnant Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 2008;53:150–4.

Logie CH, Okumu M, Mwima SP, Kyambadde P, Hakiza R, Kibathi IP, et al. Exploring associations between adolescent sexual and reproductive health stigma and HIV testing awareness and uptake among urban refugee and displaced youth in Kampala, Uganda. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2019;27:86–106.

Logie CH, Khoshnood K, Okumu M, Rashid SF, Senova F, Meghari H, et al. Self care interventions could advance sexual and reproductive health in humanitarian settings. BMJ. 2019;365:l1083–l1083.

Logie CH, Okumu M, Mwima S, Kyambadde P, Hakiza R, Kibathi IP, et al. Sexually transmitted infection testing awareness, uptake and diagnosis among urban refugee and displaced youth living in informal settlements in Kampala, Uganda: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2020;46:192–9.

Logie CH, Okumu M, Mwima S, Hakiza R, Abela H, Kyambadde P. Gender, transactional sex, and HIV prevention cascade engagement among urban refugee and displaced adolescents and youth in Kampala, Uganda. AIDS Care. 2021;33:897–903.

Logie CH, Okumu M, Kibuuka Musoke D, Hakiza R, Mwima S, Kyambadde P, et al. Intersecting stigma and HIV testing practices among urban refugee adolescents and youth in Kampala, Uganda: qualitative findings. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24: e25674.

Logie CH, Okumu M, Malama K, Mwima S, Hakiza R, Kiera UM, et al. Examining the substance use, violence, and HIV and AIDS (SAVA) syndemic among urban refugee youth in Kampala, Uganda: cross-sectional survey findings. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7: e006583.

Logie CH, Okumu M, Latif M, Parker S, Hakiza R, Kibuuka Musoke D, et al. Relational Factors and HIV Testing Practices: Qualitative Insights from Urban Refugee Youth in Kampala, Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2022;26:2191–202.

López Z, Marín S, López G, Leyva R, Ruiz Rodriguez M. Sexually transmitted diseases and AIDS vulnerability in women in forced displacement situation, Medellin, Colombia. Investigación y Educación en Enfermería. 2010;28:11–22.

Malama K, Logie C, Okumu M, Hazika R, Mwima S, Kyambadde P. Factors associated with motherhood among urban refugee adolescent girls and young women in informal settlements in Kampala, Uganda. Women & Health. 2023;63:51–8.

Márquez-Lameda RD. Predisposing and enabling factors associated with Venezuelan migrant and refugee women’s access to sexual and reproductive health care services and contraceptive usage in Peru. J Migr Health. 2022;5: 100107.

Masterson A, Usta J, Gupta J, Ettinger AS. Assessment of reproductive health and violence against women among displaced Syrians in Lebanon. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14:25.

Mendelsohn JB, Spiegel P, Schilperoord M, Balasundaram S, Radhakrishnan A, Lee C, et al. Acceptable adherence and treatment outcomes among refugees and host community on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in an urban refugee setting in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15.

Mendelsohn JB, Schilperoord M, Spiegel P, Balasundaram S, Radhakrishnan A, Lee CKC, et al. Is Forced Migration a Barrier to Treatment Success? Similar HIV Treatment Outcomes Among Refugees and a Surrounding Host Community in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:323–34.

Mendelsohn JB, Rhodes T, Spiegel P, Schilperoord M, Burton JW, Balasundaram S, et al. Bounded agency in humanitarian settings: A qualitative study of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among refugees situated in Kenya and Malaysia. Soc Sci Med. 2014;120:387–95.

Morof DF, Sami S, Mangeni M, Blanton C, Cardozo BL, Tomczyk B. A cross-sectional survey on gender-based violence and mental health among female urban refugees and asylum seekers in Kampala, Uganda. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2014;127:138–43.

Okumu M, Logie CH, Ansong D, Mwima S, Hakiza R, Newman PA. Support for Texting-Based Condom Negotiation Among Forcibly Displaced Adolescents in the Slums of Kampala, Uganda: Cross-sectional Validation of the Condom Use Negotiated Experiences Through Technology Scale. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022;8: e27792.

Okumu M, Logie CH, Ansong D, Mwima S, Hakiza R, Newman PA. Digital technologies, equitable gender norms, and sexual health practices across sexting patterns among forcibly displaced adolescents in the slums of Kampala, Uganda. Comput Human Behav. 2023;138:107453.

Olupot-Olupot P, Katawera A, Cooper C, Small W, Anema A, Mills E. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among a conflict-affected population in Northeastern Uganda: a qualitative study. AIDS. 2008;22:1882.

Pardhi A, Jungari S, Kale P, Bomble P. Migrant motherhood: Maternal and child health care utilization of forced migrants in Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;110:104823.

Patel S, Schechter MT, Sewankambo NK, Atim S, Kiwanuka N, Spittal PM. Lost in Transition: HIV Prevalence and Correlates of Infection among Young People Living in Post-Emergency Phase Transit Camps in Gulu District, Northern Uganda. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89786.

Rayamajhi RB, Budhathoki SS, Ghimire A, Neupane B, Paudel A, Paudel KM, et al. A descriptive study on use of family planning methods by married reproductive aged women in Bhutanese refugee camps of eastern Nepal. Journal of Chitwan Medical College. 2016;6:44–8.

Roupetz S, Garbern S, Michael S, Bergquist H, Glaesmer H, Bartels SA. Continuum of sexual and gender-based violence risks among Syrian refugee women and girls in Lebanon. BMC Women’s Health. 2020;20:176.

Sipsma HL, Falb KL, Willie T, Bradley EH, Bienkowski L, Meerdink N, et al. Violence against Congolese refugee women in Rwanda and mental health: a cross-sectional study using latent class analysis. BMJ Open. 2015;5: e006299.

Tohme J, Egan JE, Friedman MR, Stall R. Psycho-social Correlates of Condom Use and HIV Testing among MSM Refugees in Beirut, Lebanon. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:417–25.

Tohme J, Egan JE, Stall R, Wagner G, Mokhbat J. HIV Prevalence and Demographic Determinants of Unprotected Anal Sex and HIV Testing among Male Refugees Who have Sex with Men in Beirut, Lebanon. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:408–16.

Yaman Sözbir Ş, Erenoğlu R, Ayaz AS. Birth Experience in Syrian Refugee Women in Turkey: A Descriptive Phenomenological Qualitative Study. Women Health. 2021;61:470–8.

Wako E, Elliott L, De Jesus S, Zotti ME, Swahn MH, Beltrami J. Conflict, Displacement, and IPV: Findings From Two Congolese Refugee Camps in Rwanda. Violence Against Women. 2015;21:1087–101.

Wirtz AL, Glass N, Pham K, Aberra A, Rubenstein LS, Singh S, et al. Development of a screening tool to identify female survivors of gender-based violence in a humanitarian setting: qualitative evidence from research among refugees in Ethiopia. Confl Heal. 2013;7:13.

Wringe A, Yankah E, Parks T, Mohamed O, Saleh M, Speed O, et al. Altered social trajectories and risks of violence among young Syrian women seeking refuge in Turkey: a qualitative study. BMC Women’s Health. 2019;19:9.

Logie CH, Okumu M, Mwima S, Hakiza R, Irungi KP, Kyambadde P, et al. Social ecological factors associated with experiencing violence among urban refugee and displaced adolescent girls and young women in informal settlements in Kampala, Uganda: a cross-sectional study. Confl Heal. 2019;13:60.

Logie CH, Okumu M, Berry I, Loutet M, Hakiza R, Kibuuka Musoke D, et al. Social contextual factors associated with lifetime HIV testing among the Tushirikiane urban refugee youth cohort in Kampala, Uganda: Cross-sectional findings. Int J STD AIDS. 2022;33:374–84.

Patel SH, Muyinda H, Sewankambo NK, Oyat G, Atim S, Spittal PM. In the face of war: examining sexual vulnerabilities of Acholi adolescent girls living in displacement camps in conflict-affected Northern Uganda. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2012;12:38.

Women’s Refugee Commission. Reproductive Health Uganda: Bringing Mobile Clinics to Urban Refugees in Kampala. 2017. Available from: https://www.alnap.org/help-library/bringing-mobile-clinics-to-urban-refugees-in-kampala.

Pittaway E. Making Mainstreaming a Reality: Gender and the UNHCR Policy on Refugee Protection and Solutions in Urban Areas. A Refugee Perspective. UNHCR. [cited 2023 Jan 14]. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/protection/hcdialogue /4b0bb83f9/making-mainstreaming-reality-gender-unhcr-policy-refugee-protection-solutions.html

Chowdhury SA, Green L, Kaljee L, McHale T, Mishori, R. Sexual Violence, Trauma, and Neglect: Observations of Health Care Providers Treating Rohingya Survivors in Refugee Camps in Bangladesh. Physicians for Human Rights (PHR), 2020. Available from: https://phr.org/our-work/resources/sexual-violence-trauma-and-neglect-observations-of-health-care-providers-treating-rohingya-survivors-in-refugee-camps-in-bangladesh/.

McGinn T, Casey S, Purdin S, Marsh M. Network Paper 45: Reproductive Health for Conflict-affected People. Humanitarian Practice Network; 2004. Available from: https://www.alnap.org/help-library/network-paper-45-reproductive-health-for-conflict-affected-people

UNHCR. Inter-agency global evaluation of reproductive health services for refugees and internally displaced persons. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; 2004. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/41c846f44.pdf

United Nations Population Fund. Assessment Report on Sexual Violence in Kosovo - Serbia. 1999 [cited 2023 Jan 14]. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/serbia/assessment-report-sexual-violence-kosovo

Women’s Refugee Commission. Earning Money/Staying Safe: The Links Between Making a Living and Sexual Violence for Refugee Women in Cairo. 2008. Available from: https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/livelihoods_cairo.pdf

Schmeidl S, Tyler D. Listening to Women and Girls Displaced to Urban Afghanistan. Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC); 2015. Available from: https://www.alnap.org/help-library/listening-to-women-and-girls-displaced-to-urban-afghanistan.

Hough C. Newcomers to Nairobi: the protection concerns and survival strategies of asylum seekers in Kenya’s capital city. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; 2013. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/research/working/51f6813b9/newcomers-nairobi-protection-concerns-survival-strategies-asylum-seekers.html

Maydaa C, Chayya C, Myrttinen H. Impacts of the Syrian Civil War and Displacement on Sogiesc Populations. MOSAIC and Gender Justice and Security; 2020. Available from: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5dc436cb2cf9b86e830bb03b/t/5fe3789a99adbc5413cd5f20/1608743079483/IMPACTS+OF+THE+SYRIAN+CIVIL+WAR+AND+DISPLACEMENT+ON+SOGIESC+POPULATIONS+_+MOSAIC+_+GCRF.pdf

Krause-Vilmar J, Chaffin J. No Place to Go But Up: Urban Refugees in Johannesburg, South Africa. Women’s Refugee Commission; 2011. Available from: https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/no_place_to_go_but_up-urban_refugees_in_johannesburg.pdf

International Rescue Committee. Cross-Sectoral Assessment of Syrian Refugees in Urban Areas of South and Central Jordan. International Rescue Committee; 2013. Available from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/38299

Pavanello S, Elhawary S, Pantuliano S. Hidden and exposed: Urban refugees in Nairobi, Kenya. Overseas Development Institute; 2010. Available from: https://cdn.odi.org/media/documents/5858.pdf

Metcalfe V, Pavanello S, Mishra P. Sanctuary in the city? Urban displacement and vulnerability in Nairobi. Overseas Development Institute; 2011. Available from: https://cdn.odi.org/media/documents/7289.pdf

Washington K, Rowell J. Syrian refugees in Urban Jordan: Baseline Assessment of Community-Identified Vulnerabilities among Syrian Refugees living in Irbid, Madaba, Mufraq, and Zarqa. CARE Jordan; 2013. Available from: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/37478

Croome A, Hussein M. Climate crisis, gender inequalities and local response in Somalia/Somaliland. Forced Migration Review. 2020;25–8.

Linn S. Women refugees, leisure space and the city. Forced Migration Review. 2020;36–8.

Zapata Y. Places of refuge and risk: lessons from San Pedro Sula. Forced Migr Rev. 2020;55–8.

Chynowth S, Martin S. Ethics and accountability in researching sexual violence against men and boys. Forced Migr Rev. 2019;23–5.

Bray-Watkins S. Breaking the silence: sexual coercion and abuse in post-conflict education. Forced Migration Review. 2019;13–5.

Some. GBV in post-election Kenya. Forced Migration Review. 2008;56.

Kagwanja P. Ethnicity, gender and violence in Kenya. Forced Migration Review. 2000;22–5.

UNHCR. Designing appropriate interventions in urban settings: Health, education, livelihoods and registration for urban refugees and returnees. UNHCR. 2009. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/protection/hcdialogue/4b2789779/designing-appropriate-interventions-urban-settings-health-education-livelihoods.html.

Rosenberg J. Case Study: Strengthening GBV Prevention & Response in Urban Contexts. The Women’s Refugee Commission; 2016. Available from: https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/GBV-Task-Forces-Delhi.pdf

Rosenberg J. New Strategies to Address GBV in Urban Humanitarian Settings. Women’s Refugee Commission. 2017. Available from: https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/blog/new-strategies-to-address-gbv-in-urban-humanitarian-settings/.

Rosenberg J. Mean Streets: Identifying and Responding to Urban Refugees’ Risks of Gender-Based Violence. Women’s Refugee Commission; 2016.

Women’s Refugee Comission, Reproductive Health Uganda. Working with Refugee Women Engaged in Sex Work: Bringing a Peer Education Model and Mobile Clinics to Refugees in Cities. Kampala and Nakivale Settlement, Uganda: Women’s Refugee Comission; 2017 Jun. Available from: https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/research-resources/kampala-supporting-refugee-women-engaged-in-sex-work-through-the-peer-education-model-bringing-mobile-health-clinics-to-refugee-neighborhoods/

Women’s Refugee Comission. Supporting Transwomen Refugees: Tailoring activities to provide psychosocial support and build peer networks among refugee and host community transwomen. Beirut, Lebanon: Women’s Refugee Comission; 2017 Mar. Available from: https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/research-resources/urban-gbv-case-studies/

Women’s Refugee Comission, Don Bosco. GBV Task Forces in Delhi, India. Women’s Refugee Comission; 2017 Jun. Available from: https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/research-resources/delhi-developing-refugee-led-gbv-task-forces/

Coker E, Bichard A, Nannipieri A, Wani J. Health education for urban refugees in Cairo: A pilot project with young men from Sierra Leone and Liberia. The American University in Cairo; 2003.

Women’s Refugee Comission, Save the Children, UNCHR, UNFPA. Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Programs in Humanitarian Settings: An In-depth Look at Family Planning Services, December 2012. 2012 Dec. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/protection/health/51b875ed9/adolescent-sexual-reproductive-health-programs-humanitarian-settings-in.html

UNHCR. Health Access and Utilization Survey Among Syrian Refugees in Lebanon. UNHCR; 2016. Available from: https://www.alnap.org/help-library/health-access-and-utilization-survey-among-syrian-refugees-in-lebanon

Tanab M, Nagujja Y. “We have a right to love” - The Intersection of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Disability for Urban Refugees in Kampala, Uganda. Women’s Refugee Commission; 2014. Available from: https://www.refworld.org/docid/57ff6fa54.html

Jaffer F, Guy S, Niewczasinski J. Reproductive health care for Somali refugees in Yemen. Forced Migration Review. 2004;33–4.

Popinchalk A. HIV/AIDS services for refugees in Egypt. Forced Migration Review. 2008;69–70.

Quintero A, Culler T. IDP health in Colombia: needs and challenges. Forced Migration Review. 2009;70–1.

Sánchez CIP, Enríquez C. Sexual and reproductive health rights of Colombian IDPs. Forced Migration Review. 2004;19:31–2.

Wells M, Kuttiparambil G. Humanitarian action and the transformation of gender relations. Forced Migration Review. 2016;20–2.

Mcleroy K, Bibeau DL. An Ecology Perspective on Health Promotion Programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–77.

Baral S, Logie CH, Grosso A, Wirtz AL, Beyrer C. Modified social ecological model: A tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1–1.

Singh NS, Aryasinghe S, Smith J, Khosla R, Say L, Blanchet K. A long way to go: a systematic review to assess the utilisation of sexual and reproductive health services during humanitarian crises. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3:e000682–e000682.

Stangl AL, Earnshaw VA, Logie CH, van Brakel W, Simbayi L, Barre I, et al. The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: a global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med. 2019;17:31.

Ezeh A, Oyebode O, Satterthwaite D, Chen Y-F, Ndugwa R, Sartori J, et al. The history, geography, and sociology of slums and the health problems of people who live in slums. The Lancet. 2017;389:547–58.

Logie CH, van der Merwe LL-A, Scheim AI. Measuring sex, gender, and sexual orientation : one step to health equity. The Lancet. 2022;6736:8–10.

Argento E, Goldenberg S, Shannon K. Preventing sexually transmitted and blood borne infections (STBBIs) among sex workers: a critical review of the evidence on determinants and interventions in high-income countries. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:212–212.

Buse K, Albers E, Phurailatpam S. HIV and drugs: a common, common-sense agenda for 2016. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4:e292–3.

Nyblade L, Stockton MA, Giger K, Bond V, Ekstrand ML, Lean RM, et al. Stigma in health facilities: why it matters and how we can change it. BMC Med. 2019;17:25–25.

Narasimhan M, Allotey P, Hardon A. Self care interventions to advance health and wellbeing: a conceptual framework to inform normative guidance. BMJ. 2019;365:l688–l688.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of the University of Toronto librarians.

Funding

CHL received funding from the Canada Research Chairs Program and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). They played no role in the research process, focus, analysis or other aspects of research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CHL conceptualized the study and led the writing. FM substantially contributed to writing the manuscript as well as screening, data extraction and synthesis. FM, KM, NL, AL, KD, MZ, conducted the searches, screening and extraction. APB contributed to drafting and editing the manuscript. MN, SF, BT, JK, KK and ABP contributed to editing the manuscript and providing interpretation of findings. CHL, AH, and FM contributed to the revision process. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable (no original data collected).

Consent for publication

Not applicable (no original data collected).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Logie, C.H., MacKenzie, F., Malama, K. et al. Sexual and reproductive health among forcibly displaced persons in urban environments in low and middle-income countries: scoping review findings. Reprod Health 21, 51 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-024-01780-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-024-01780-7