Abstract

Background

The frequency of antenatal care utilization enhances the effectiveness of the maternal health programs to maternal and child health. The aim of the study was to determine the number of antenatal care and associated factors in Ethiopia by using 2019 intermediate EDHS.

Methods

Secondary data analysis was done on 2019 intermediate EDHS. A total of 3916.6 weighted pregnant women were included in the analysis. Zero-inflated Poisson regression analysis was done by Stata version 14.0. Incident rate ratio and odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval were used to show the strength and direction of the association.

Result

About one thousand six hundred eighty eight (43.11%) women were attending four and more antenatal care during current pregnancy. Attending primary education (IRR = 1.115, 95% CI: 1.061, 1.172), secondary education (IRR = 1.211, 95% CI: 1.131, 1.297) and higher education (IRR = 1.274, 95% CI: 1.177, 1.378), reside in poorer household wealth index (IRR = 1.074, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.152), middle household wealth index (IRR = 1.095, 95% CI: 1.018, 1.178), rich household wealth index (IRR = 1.129, 95% CI: 1.05, 1.212) and richer household wealth index (IRR = 1.186, 95% CI: 1.089, 1.29) increases the number of antenatal care utilization. The frequency of antenatal care was less likely become zero among women attending primary (AOR = 0.434, 95% CI: 0.346, 0.545), secondary (AOR = 0.113, 95% CI: 0.053, 0.24), higher educational level (AOR = 0.052, 95% CI: 0.007, 0.367) in the inflated part.

Conclusion

The number of antenatal care utilization is low in Ethiopia. Being rural, poorest household index, uneducated and single were factors associated with low number of antenatal care and not attending antenatal care at all. Improving educational coverage and wealth status of women is important to increase the coverage and frequency of antenatal care.

Plain language summary

Antenatal care is among the most effective interventions to mitigate maternal mortality and morbidity. It is an entry point for delivery care, postnatal care and child immunization. This study was conducted to determine the frequency and associated factors of antenatal care utilization in Ethiopia by using 2019 intermediate Ethiopian Demography Health Survey.

A cross-sectional study design using secondary data from 2019 intermediate Ethiopian demography and health survey was conducted. 3917 weighted women were included in the study. Recoding, variable generation, labeling and analysis were done by using STATA/SE version 14.0.

The objective of this study was to identify the determinants of frequency of antenatal care visit in Ethiopia by using zero inflated Poisson regression.

In this study 74.38% of women attend antenatal care at least once during their current pregnancy. Only 41.8% of women use WHO recommended number of antenatal care.

Conclusion: maternal age, residence, educational status, household wealth index, religion and region show significant association with the frequency of antenatal care utilization. Advocacy and behavioral change communication should be area of concern for different organizations that are working on antenatal care especially for rural, poor and uneducated women through mass campaign, community dialoging and enhance the effectiveness of health extension programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Maternal mortality is global public health problem [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. The problem is disproportionally high in developing countries including Ethiopia [2, 3, 8]. Pregnant women suffer from direct and indirect pregnancy related complications [2, 9,10,11,12,13,14]. Reproductive health is a global agendum for the last 50 years [15,16,17,18]. Despites the global efforts, reproductive health problems of women are not addressed [4, 6, 7, 9, 12, 19,20,21,22].

Antenatal care is among the most effective interventions to mitigate maternal and child mortality and morbidity [23,24,25]. It is an entry point for delivery care, postnatal care and child immunization. It also makes link between the health provider and the clint for further interventions [25,26,27,28,29]. During ANC pregnancy related complications, pre-existing health conditions are screened, diagnosed and appropriate interventions are delivered for pregnant women. Behavioral change communication on personal hygiene, utilization of available services and interventions are provided for the women and the family at large [23, 25, 27, 30,31,32].

Now a day’s ANC address a wide range services including, identifying threats during the prenatal period, birth preparedness and complication readiness, family planning, child feeding options and nutritional counseling during pregnancy and after birth [22, 28, 29, 31, 33,34,35]. WHO guide line recommends at least four ANC for normal pregnancy and extra visit for women with complications. The first visit is recommended in the first trimester which is predicted to screen and treat anemia, syphilis, HIV testing and counseling (HTC) and screen for risk factors and medical conditions. The second, third and fourth visits are scheduled at 24–28, 32 and 36 weeks, respectively to monitor fetal and maternal conditions [34].

In Ethiopia, maternal mortality ratio is high (412 per 10,000 life birth) [36]. The country has reproductive strategy for the last 20 years. ANC services are available to the country side and included in health extension package. ANC utilization is increased through time. But it still low [37].

In Ethiopia, different researches have been done on prevalence and/or factors associated with ANC utilization [35, 38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. Maternal educational status, age, residence, accessing radio, wealth index, pregnancy status, number of children, accessibility of health facilities, occupation and religion are determinant factors identified by scholars [50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63]. But, all the studies were done at local level with small sample size. There were studies in the Ethiopia by using Ethiopian demography and health surve-2016 by using logistic regression. However, it results loss of information, due to count nature of the outcome variable. More over recent national representative evidence is scarce. As a result in this study we account methodological limitation of previous studies by using count data analysis using recent national data. So the aim of this study was to determine the frequency and associated factors of antenatal care utilization in Ethiopia by using 2019 intermediate Ethiopian Demography Health Survey.

Method

Study setting and period

The study was conducted in Ethiopia, which is located in the North-eastern (horn of) Africa, lies between 3° and 15° North latitude and 33° 48° and East longitudes. This study used the intermediate EDHS 2019 dataset which was conducted by the Central Statistical Agency in collaboration with the federal Ministry of Health (FMoH) and the Ethiopian Public Health Institute. Data were accessed from their URL: www.dhsprogram.com by contacting them through personal accounts after justifying the reason for requesting the data. Then reviewing the account permission was given via the email. A cross-sectional study design using secondary data from 2019 intermediate Ethiopian demography and health survey was conducted.

Sampling procedure

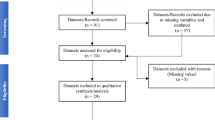

The intermediate EDHS 2019 sample was stratified and selected in two stages. In the first stage, stratification was conducted by region and then each region stratified as urban and rural, yielding 21 sampling strata. A total of 305 (94 urban 211 rural) enumeration areas (EAs) were selected with probability proportional to EA size in each sampling stratum. In the second stage households were selected proportionally from each EA by using systematic sampling method.3, 916.7 weighted women were included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Study variables

The outcome variable of this study was the number of ANC visits during last pregnancy. The independent variables include; women’s age, religion, current marital status, residence, educational level, household wealth index, region and number of children.

Variable measurement

The number of antenatal care was measured as account data between 0 and 20. The regions were categorized in to three as urban (Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa), developed (Tigray, Amhara, Oromia and South Nations Nationalities people) and the rest (Afar, Somali, Gambella and Benishangul Gumz) were leveled as developing regions.

Data processing and analysis

Data cleaning was conducted to check for the consistency with the EMDHS 2019 descriptive report. Recoding, variable generation, labeling and analysis were done by using STATA/SE version 14.0. Since ANC follow up (dependent variable) is a non-negative integer, most of the recent thinking in the field has used the Poisson regression model as a starting point. To run Poisson regression, mean and variance should be equal. In the current case the mean and the variance were 2.89 and 5.33 respectively. So the assumption is violated. That is the data were over dispersed. To handle over-dispersion and excess zeros in the data, we have considered zero inflated Poisson models, the extension of Poisson regression to have precise result [50].

The analysis was done for both count part and the zero inflated part. Finally incident rate ratio and odds ratio were presented with 95% CI. Statistical significance was determined at a P value of less than 0.05.

Results

From weighted 3916.7 pregnant women, 1688.3(43.11%) women use four and more antenatal care during current pregnancy. About 1003.5 (25.62%) women do not attend antenatal care during pregnancy. The mean and the variance of observations are 2.89 and 5.33 respectively (Table1).

Selection of model

Poisson regression, negative binomial regression and zero-inflated Poisson regression are tested to select model for analysis. Zero-inflated model has good log likelihood test (− 5692.033) than the two models. The Vuong test (< 0.001) indicates there is statistical difference between Poisson regression and zero-inflated Poisson regression (Table 2).

Magnitude of ANC utilization among pregnant women in Ethiopia, 2019

The lowest mean numbers of ANC visits were observed from 45 to 49 age group women (1.94), while the highest visits were observed from 30 to 34 age group women (3.03) and 25–29 years old women (3.07). There was a significant difference on the mean number of ANC visits among some age groups. A significantly high mean numbers ANC visits were recorded in Orthodox religion followers (3.69). As educational level increases the mean numbers of ANC visits were significantly increased. The lowest mean was observed in uneducated women (2.18) and the highest was among women who attended higher educational level (5.02).

The lowest mean numbers of ANC visits were recorded among women who lived in the poorest household wealth index (1.63). The highest numbers of ANC visits were observed in urban dweller women (4.2). There is significant difference on the mean numbers of ANC visits across regions. The highest mean was observed in women who lived in urban regions (4.02) and the lowest was among women who lived in developing regions (2.15) (Table3).

Factors associated with frequency of antenatal care

In the Poisson model, maternal age, residence, educational status, household wealth index, religion and region shows significant association with the frequency of antenatal care utilization.

The frequency of antenatal visit was 1.17 (IRR = 1.74, 95% CI: 1.052, 1.31) and 1.23 (IRR = 1.233, 95% CI: 1.075, 1.414) times higher among 30–34 years and 40–44 years women than 15–19 years women respectively.

The number of antenatal care visit was 12.7% (IRR = 0.873, 95% CI: 0.826, 0.924), 5.3% (IRR = 0.947, 95% CI: 0.903, 0.994) times more among Orthodox followers than Protestant and Muslim religious followers respectively.

Women attending primary education (IRR = 1.115, 95% CI: 1.061, 1.172), secondary education (IRR = 1.211, 95% CI: 1.131, 1.297) and higher education (IRR = 1.274, 95% CI: 1.177, 1.378) had high number of antenatal care visit than uneducated women. Women reside in poorer household wealth index (IRR = 1.074, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.152), middle household wealth index (IRR = 1.095, 95% CI: 1.018, 1.178), rich household wealth index (IRR = 1.129, 95% CI: 1.05, 1.212) and richer household wealth index (IRR = 1.186, 95% CI: 1.089, 1.29) had significantly high frequency of antenatal care. Urban dweller women had (IRR = 1.096, 95% CI: 1.028, 1.169) significantly high number of antenatal care follow up than rural dwellers.

In the zero inflated model, maternal age, marital status, educational status, household wealth index and religion shows significant association with antenatal care service utilization uptake becomes zero.

The number of antenatal care was 47.5%, 49.3% and 43.7% less likely became zero among 25–29 years old women (AOR = 0.525, 95% CI: 0.337, 0.816), 30–34 years old women (AOR = 0.507, 95% CI: 0.313, 0.819) and 35–39 years old women (AOR = 0.563, 95% CI: 0.34, 0.934) when compared with 15–19 years old women. The frequency of antenatal care was 56.6%, 88.7% and 94.8% less likely become zero among women attending primary (AOR = 0.434 95% CI: 0.346, 0.545), secondary (AOR = 0.113, 95% CI: 0.053, 0.24) and higher educational level (AOR = 0.052, 95%CI: 0.007, 0.367) than non-educated women respectively.

The number of antenatal care was 2.3 and 2.5 times more become zero among Protestant (AOR = 2.342, 95% CI: 1.749, 3.136) and Muslim religious followers (AOR = 2.512, 95% CI: 1.865, 3.284) than orthodox followers respectively (Table 4).

Discussion

The objective of this study was to identify the determinants of frequency of antenatal care visit in Ethiopia by using zero inflated Poisson regression.

In this study 74.38% of women attend antenatal care at least once during their current pregnancy. The finding is consistent with researches in Afghanistan (69.3%) [64], Southern Ethiopia (76.2%) [40], Zambia (69%) [65], Nepal (76.0%) [66]. The finding is higher than the study in Benishangul Gumuz Region, Ethiopia (37.7%) [62], Nigeria (65.1%) [67], Eastern Ethiopia (53.6%) [59]. The finding was lower than studies in Southwestern Ethiopia (91.9) [68], Ghana (98.3%) [69], Pakistan (83.5%) [70], Guinea (80.3%) [55]. The finding indicates, the country needs more effort to improve the coverage of ANC. Since all pregnant women should attend ANC at least once during pregnancy.

In this study, only 41.8% of women use WHO recommended number of antenatal care. The finding is lower than studies in Rwanda (54%) [71], sub-Saharan countries (58.53) [61], India (51.7%) [72], Nigeria (56.2%) [67] and Pakistan (57.3) [70]. The finding is higher than findings in Bangladesh (32%) [73], Eastern Ethiopia (15.3%) [59] and Zambia (29%) [65]. The difference might be due to study population coverage, study setting and time. The finding shows there is a gap between the country health transformation plan (95%) and the situation in the ground (41.8%). It indicates different stake holders should work to increase the frequency of ANC to reduce maternal and child mortality.

Women in the middle age group have high frequency of antenatal care utilization. The probability of antenatal care utilization not zero is lower in this group of women. The result is similar with findings in Ethiopia [51], Uganda [74], Bangladesh [75], East African Countries [60], Nigeria [76, 77]. Middle age women might experiences previous pregnancy related complications that make them conscious to use maternal health services [54, 78, 79].

The frequency of antenatal care visit was high in urban dwellers than rural residents. The finding is in line with previous researches [55, 56, 64, 80]. Urban residence reduces distance to get services [81,82,83,84]. Rural dwellers might face transportation problem to access the service [78, 79, 85, 86]. Moreover, urban dwellers might have mass media accesses on importance of antenatal care [61, 87,88,89]. Since 74% of (Table 3) women resided in rural part of the country, more effort is expected from the government to increase the number of ANC at national level.

The frequency of antenatal care increases as the educational status of the women was increased. The odds of not attending antenatal care service were reduced when educational status is increased. The finding was supported by previous researches in Western Ethiopia [62], Ethiopia [56], rural Ethiopia [51], Kenya [90], Guinea [55, 91], Afghanistan [64], Angola [54], East African countries [60], India [92, 93], Ghana [94], Nepal [95], Nigeria [96]. Educated women might empowered to get services [97,98,99,100,101,102], education make women to have decision making [103, 104]. Moreover educated women have knowledge on danger sign [105,106,107,108]. Educated women might have awareness on the advantage of antenatal care different services provided in the service delivery points for the fetus and herself [53, 109,110,111].

As the household wealth index increases the frequency of antenatal care service utilization is increased and decreases the probability of not taking antenatal care services. The estimated IRR and OR, indicates that the probability no antenatal care take and the frequency of ANC visits increased with increasing household wealth status. The result was consistent with other findings in Western Ethiopia [62], Nepal [112], Guinea [55, 113], Angola [54], Nigeria [67], India [72], Ghana [69] Bangladesh [73, 102]. It might be due to women who belong to rich household usually have higher [114, 115] educational status, access to mass media [55, 116,117,118], and an ability to spend more money to take frequent ANC visits compared to women from poorer families [119,120,121].

There was religious variation on the frequency and utilization of antenatal care. Orthodox religion followers have high number of antenatal care utilization than Protestant and Muslim religious followers. Studies suggest there is religious variation on utilization and frequency antenatal care [75, 122, 123]. Further qualitative research might be needed to have more information on the effect of religion on utilization of ANC.

The odds of not antenatal care were less in married and widowed/divorced women than single women. The result is consistent with findings in Rwanda [83], Debre Berhan [124], Benin [125], Middle and low income countries [126]. Married women might get partner support to attend antenatal care [55, 127, 128]. Moreover, single women might face stigma to use antenatal care services by the community and health care workers [129,130,131].

Women who lived in developing regions had low frequency of antenatal care utilization than women who resided in urban areas. The finding is agreed with previous researches in different parts of Africa [54, 56, 132, 133]. There might be differences in socio-cultural, power relationships, accessibility of service in different parts of the country.

The result of this study was more representative than other studies and the model considered different levels of analysis as the outcome was count data. Despite this strength, the result may be prone to recall bias because the data were collected from a history of the event and some variables were missed since the data set was intermediate. Due to the nature of the data set, quality related data, previous exposure variables, paternal variables were not included.

Conclusion

Utilization of minimum number of antenatal care utilization is low in Ethiopia. Being in middle age group, urban residence, increased educational level, improved household wealth status, Orthodox religious follower increases the number of antenatal care utilization.

Being middle age group, married, increased educational status, improved household wealth status; Orthodox religion follower decreases the probability of not attending antenatal care. Advocacy and behavioral change communication should be area of concern for different organizations that are working on antenatal care especially for rural, poor and uneducated women through mass campaign, community dialoging and enhance the effectiveness of health extension programs. Further, qualitative research would be needed to get detail information how religion was affect the frequency of ANC.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CSA:

-

Central Statistics Agency

- EA:

-

Enumeration area

References

Bauserman M, Thorsten VR, Nolen TL, Patterson J, Lokangaka A, Tshefu A, et al. Maternal mortality in six low and lower-middle income countries from 2010 to 2018: risk factors and trends. Reprod Health. 2020;17(3):1–10.

Geller SE, Koch AR, Garland CE, MacDonald EJ, Storey F, Lawton B. A global view of severe maternal morbidity: moving beyond maternal mortality. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):31–43.

Girum T, Wasie A. Correlates of maternal mortality in developing countries: an ecological study in 82 countries. Maternal Health Neonatol Perinatol. 2017;3(1):1–6.

WHO. Maternal mortality. 2018.

Martins ACS, Silva LS. Epidemiological profile of maternal mortality. Rev Bras Enferm. 2018;71:677–83.

Organization WH. Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2017: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. 2019.

Ozimek JA, Kilpatrick SJ. Maternal mortality in the twenty-first century. Obstetr Gynecol Clin. 2018;45(2):175–86.

Ronsmans C, Graham WJ, Group LMSSs. Maternal mortality: who, when, where, and why. Lancet. 2006;368(9542):1189–200.

Cirelli JF, Surita FG, Costa ML, Parpinelli MA, Haddad SM, Cecatti JG. The burden of indirect causes of maternal morbidity and mortality in the process of obstetric transition: a cross-sectional multicenter study. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstetr. 2018;40(3):106–14.

England N, Madill J, Metcalfe A, Magee L, Cooper S, Salmon C, et al. Monitoring maternal near miss/severe maternal morbidity: a systematic review of global practices. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(5): e0233697.

Filippi V, Chou D, Barreix M, Say L, Group WMMW, Barbour K, et al. A new conceptual framework for maternal morbidity. Int J Gynecol Obstetr. 2018;141:4–9.

Say L, Chou D, Group WMMW, Barbour K, Barreix M, Cecatti JG, et al. Maternal morbidity: time for reflection, recognition, and action. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;141(Suppl. 1):1–3

Small MJ, Allen TK, Brown HL. Global disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality. Semin Perinatol. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2017.04.009.

Tura AK, Trang TL, Van Den Akker T, Van Roosmalen J, Scherjon S, Zwart J, et al. Applicability of the WHO maternal near miss tool in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):1–9.

Yamey G, Shretta R, Binka FN. The 2030 sustainable development goal for health. Br Med J. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g5295.

WHO. Millennium development goals. 2008.

Cohen SA, Richards CL. The Cairo consensus: population, development and women. Fam Plann Perspect. 1994;26(6):272–7.

Organization WH. Department of Reproductive Health and Research, including UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction annual technical report. World Health Organization; 2001.

Boerma T, Requejo J, Victora CG, Amouzou A, George A, Agyepong I, et al. Countdown to 2030: tracking progress towards universal coverage for reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health. Lancet. 2018;391(10129):1538–48.

Chowdhury MAB, Adnan MM, Hassan MZ. Trends, prevalence and risk factors of overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age in Bangladesh: a pooled analysis of five national cross-sectional surveys. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7): e018468.

Wirth JP, Woodruff BA, Engle-Stone R, Namaste SM, Temple VJ, Petry N, et al. Predictors of anemia in women of reproductive age: Biomarkers Reflecting Inflammation and Nutritional Determinants of Anemia (BRINDA) project. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(suppl_1):416S-S427.

Woog V, Kågesten A. The sexual and reproductive health needs of very young adolescents aged 10–14 in developing countries: what does the evidence show. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2017.

de Masi S, Bucagu M, Tunçalp Ö, Peña-Rosas JP, Lawrie T, Oladapo OT, et al. Integrated person-centered health care for all women during pregnancy: implementing World Health Organization recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2017;5(2):197–201.

Langlois EV, Tunçalp Ö, Norris SL, Askew I, Ghaffar A. Qualitative evidence to improve guidelines and health decision-making. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96(2):79.

Organization WH. WHO recommendations on intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience: World Health Organization; 2018.

Haddad SM, Souza RT, Cecatti JG, Barreix M, Tamrat T, Footitt C, et al. Building a digital tool for the adoption of the World Health Organization’s antenatal care recommendations: methodological intersection of evidence, clinical logic, and digital technology. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(10): e16355.

Mehl G, Tunçalp Ö, Ratanaprayul N, Tamrat T, Barreix M, Lowrance D, et al. WHO SMART guidelines: optimising country-level use of guideline recommendations in the digital age. Lancet Digit Health. 2021;3(4):e213–6.

Noij F. UNFPA CAMBODIA. 2017.

Organization WH. WHO antenatal care recommendations for a positive pregnancy experience: nutritional interventions update: vitamin D supplements during pregnancy. 2020.

Homer CS, Oats J, Middleton P, Ramson J, Diplock S. Updated clinical practice guidelines on pregnancy care. Med J Aust. 2018;209(9):409–12.

Sudfeld CR, Smith ER. New evidence should inform WHO guidelines on multiple micronutrient supplementation in pregnancy. J Nutr. 2019;149(3):359–61.

Waller A, Bryant J, Cameron E, Galal M, Symonds I, Sanson-Fisher R. Screening for recommended antenatal risk factors: how long does it take? Women Birth. 2018;31(6):489–95.

Lattof SR, Tunçalp Ö, Moran AC, Bucagu M, Chou D, Diaz T, et al. Developing measures for WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience: a conceptual framework and scoping review. BMJ Open. 2020;9(4): e024130.

WHO. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. 2016.

Kebede TT, Godana W, Utaile MM, Sebsibe YB. Effects of antenatal care service utilization on maternal near miss in Gamo Gofa zone, southern Ethiopia: retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):1–9.

Tamirat KS, Sisay MM. Full immunization coverage and its associated factors among children aged 12–23 months in Ethiopia: further analysis from the 2016 Ethiopia demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–7.

Ethiopia CSA (CSA) [Ethiopia] 2016. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA; 2017.

Abosse Z, Woldie M, Ololo S. Factors influencing antenatal care service utilization in Hadiya zone. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2010. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejhs.v20i2.69432.

Basha GW. Factors affecting the utilization of a minimum of four antenatal care services in Ethiopia. Obstetr Gynecol Int. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/5036783.

Dulla D, Daka D, Wakgari N. Antenatal care utilization and its associated factors among pregnant women in Boricha District, southern Ethiopia. Divers Equal Health Care. 2017;14(2):76–84.

Fekede B. Antenatal care services utilization and factors associated in Jimma Town (south west Ethiopia). Ethiop Med J. 2007;45(2):123–33.

Mulat G, Kassaw T, Aychiluhim M. Antenatal care service utilization and its associated factors among mothers who gave live birth in the past one year in Womberma Woreda, North West Ethiopia. Epidemiology (Sunnyvale) S. 2015. https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-1165.S2-003.

Tiruaynet K, Muchie KF. Determinants of utilization of antenatal care services in Benishangul Gumuz Region, Western Ethiopia: a study based on demographic and health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):115.

Tura G. Antenatal care service utilization and associated factors in Metekel Zone, Northwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2009. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejhs.v19i2.69415.

Woyessa AH, Ahmed TH. Assessment of focused antenatal care utilization and associated factors in Western Oromia, Nekemte, Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):1–7.

Gedefaw M, Muche B, Aychiluhem M. Current status of antenatal care utilization in the context of data conflict: the case of Dembecha District, Northwest Ethiopia. Open J Epidemiol. 2014;4(04):208.

Tsegay Y, Gebrehiwot T, Goicolea I, Edin K, Lemma H, San SM. Determinants of antenatal and delivery care utilization in Tigray region, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12(1):1–10.

Yohannes B, Tarekegn M, Paulos W. Mothers‟ Utilization of antenatal care and their satisfaction with delivery services in selected public health facilities of Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Int J Sci Technol Res. 2013;2(2):74.

Zegeye EA, Mbonigaba J, Dimbuene ZT. Factors associated with the utilization of antenatal care and prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission services in Ethiopia: applying a count regression model. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(1):1–11.

Agarwal DK, Gelfand AE, Citron-Pousty S. Zero-inflated models with application to spatial count data. Environ Ecol Stat. 2002;9(4):341–55.

Azanaw MM, Gebremariam AD, Dagnaw FT, Yisak H, Atikilt G, Minuye B, et al. Factors associated with numbers of antenatal care visits in rural Ethiopia. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:1403.

Fenta SM, Ayenew G, Getahun BE. Magnitude of antenatal care service uptake and associated factors among pregnant women: analysis of the 2016 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey. BMJ Open. 2021;11(4): e043904.

Mulat A, Kassa S, Belay G, Emishaw S, Yekoye A, Bayu H, et al. Missed antenatal care follow-up and associated factors in Eastern Zone of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Afr Health Sci. 2020;20(2):690–6.

Shibre G, Zegeye B, Idriss-Wheeler D, Ahinkorah BO, Oladimeji O, Yaya S. Socioeconomic and geographic variations in antenatal care coverage in Angola: further analysis of the 2015 demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–10.

Shibre G, Zegeye B, Idriss-Wheeler D, Yaya S. Factors affecting the utilization of antenatal care services among women in Guinea: a population-based study. Fam Pract. 2021;38(2):63–9.

Shiferaw K, Mengistie B, Gobena T, Dheresa M, Seme A. Extent of received antenatal care components in Ethiopia: a community-based panel study. Int J Women’s Health. 2021;13:803.

Tegegne TK, Chojenta C, Getachew T, Smith R, Loxton D. Antenatal care use in Ethiopia: a spatial and multilevel analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):1–16.

Tekelab T, Chojenta C, Smith R, Loxton D. Factors affecting utilization of antenatal care in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(4): e0214848.

Tesfaye G, Chojenta C, Smith R, Loxton D. Application of the Andersen-Newman model of health care utilization to understand antenatal care use in Kersa District, Eastern Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(12): e0208729.

Tessema ZT, Minyihun A. Utilization and determinants of antenatal care visits in East African Countries: a multicountry analysis of demographic and health surveys. Adv Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6623009.

Tessema ZT, Teshale AB, Tesema GA, Tamirat KS. Determinants of completing recommended antenatal care utilization in sub-Saharan from 2006 to 2018: evidence from 36 countries using demographic and health surveys. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):1–12.

Tiruaynet K, Muchie KF. Determinants of utilization of antenatal care services in Benishangul Gumuz Region, Western Ethiopia: a study based on demographic and health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):1–5.

Tolera H, Gebre-Egziabher T, Kloos H. Using Andersen’s behavioral model of health care utilization in a decentralized program to examine the use of antenatal care in rural western Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(1): e0228282.

Stanikzai MH, Wafa MH, Wasiq AW, Sayam H. Magnitude and determinants of antenatal care utilization in Kandahar city, Afghanistan. Obstetr Gynecol Int. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5201682.

Jacobs C, Moshabela M, Maswenyeho S, Lambo N, Michelo C. Predictors of antenatal care, skilled birth attendance, and postnatal care utilization among the remote and poorest rural communities of Zambia: a multilevel analysis. Front Public Health. 2017;5:11.

Awasthi MS, Awasthi KR, Thapa HS, Saud B, Pradhan S, Khatry RA. Utilization of antenatal care services in Dalit communities in Gorkha, Nepal: a cross-sectional study. J Pregnancy. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3467308.

Fagbamigbe AF, Idemudia ES. Wealth and antenatal care utilization in Nigeria: policy implications. Health Care Women Int. 2017;38(1):17–37.

Terefe AN, Gelaw AB. Determinants of antenatal care visit utilization of child-bearing mothers in Kaffa, Sheka, and Bench Maji Zones of SNNPR, Southwestern Ethiopia. Health Serv Res Manag Epidemiol. 2019;6:2333392819866620.

Ziblim S-D, Yidana A, Mohammed A-R. Determinants of antenatal care utilization among adolescent mothers in the Yendi municipality of northern region, Ghana. Ghana J Geogr. 2018;10(1):78–97.

Noh J-W, Kim Y-M, Lee LJ, Akram N, Shahid F, Kwon YD, et al. Factors associated with the use of antenatal care in Sindh province, Pakistan: a population-based study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(4): e0213987.

Rurangirwa AA, Mogren I, Nyirazinyoye L, Ntaganira J, Krantz G. Determinants of poor utilization of antenatal care services among recently delivered women in Rwanda; a population based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):1–10.

Ogbo FA, Dhami MV, Ude EM, Senanayake P, Osuagwu UL, Awosemo AO, et al. Enablers and barriers to the utilization of antenatal care services in India. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(17):3152.

Ali N, Sultana M, Sheikh N, Akram R, Mahumud RA, Asaduzzaman M, et al. Predictors of optimal antenatal care service utilization among adolescents and adult women in Bangladesh. Health Serv Res Manag Epidemiol. 2018;5:2333392818781729.

Atuhaire S, Mugisha J. Determinants of antenatal care visits and their impact on the choice of birthplace among mothers in Uganda: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol Int J. 2020;11(1):77–81.

Chanda SK, Ahammed B, Howlader MH, Ashikuzzaman M, Shovo T-E-A, Hossain MT. Factors associating different antenatal care contacts of women: a cross-sectional analysis of Bangladesh demographic and health survey 2014 data. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4): e0232257.

Ibikunle O, Asa S, Ibikunle A, Breiger W. Background determinants of antenatal care utilization among pregnant women in Akwa Ibom, Nigeria. Ife Soc Sci Rev. 2020;28(1):27–38.

Umar A. The use of maternal health services in Nigeria: does ethnicity and religious beliefs matter. MOJ Public Health. 2017;6(6):00190.

Simkhada B, Teijlingen ERV, Porter M, Simkhada P. Factors affecting the utilization of antenatal care in developing countries: systematic review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 2008;61(3):244–60.

Konlan KD, Saah JA, Amoah RM, Doat AR, Mohammed I, Abdulai JA, et al. Factors influencing the utilization of Focused antenatal care services during pregnancy, a study among postnatal women in a tertiary healthcare facility, Ghana. Nurs Open. 2020;7(6):1822–32.

Wulandari RD, Laksono AD, Rohmah N. Urban-rural disparities of antenatal care in South East Asia: a case study in the Philippines and Indonesia. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–9.

Aziz A, Fatima A, Fatima M, Hayat I, Hussain W, Sadaf J. Factors resulting in non-utilization of antenatal care services from public sector hospitals in the rural area of Bahawalpur. J Sheikh Zayed Med Coll (JSZMC). 2020;11(03):08–12.

Elmi EOH, Hussein NA, Hassan AM, Ismail AM, Abdulrahman AA, Muse AM. Antenatal care: utilization rate and barriers in Bosaso-Somalia, 2019. Eur J Prev Med. 2021;9(1):25–31.

Nisingizwe MP, Tuyisenge G, Hategeka C, Karim ME. Are perceived barriers to accessing health care associated with inadequate antenatal care visits among women of reproductive age in Rwanda? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):1–10.

Seidu A-A. A multinomial regression analysis of factors associated with antenatal care attendance among women in Papua New Guinea. Public Health Pract. 2021;2: 100161.

Ali SA, Ali SA, Feroz A, Saleem S, Fatmai Z, Kadir MM. Factors affecting the utilization of antenatal care among married women of reproductive age in the rural Thatta, Pakistan: findings from a community-based case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):1–12.

Ziegler BR, Kansanga M, Sano Y, Kangmennaang J, Kpienbaareh D, Luginaah I. Antenatal care utilization in the fragile and conflict-affected context of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Soc Sci Med. 2020;262: 113253.

Gashu KD, Yismaw AE, Gessesse DN, Yismaw YE. Factors associated with women’s exposure to mass media for Health Care Information in Ethiopia. A case-control study. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2021;12: 100833.

Jagiello Z, López-García A, Aguirre JI, Dylewski Ł. Distance to landfill and human activities affects the debris incorporation into the white stork nests in urbanized landscape in central Spain. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2020;27(24):30893–8.

Islam MA, Kabir MR, Talukder A. Triggering factors associated with the utilization of antenatal care visits in Bangladesh: an application of negative binomial regression model. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2020;8(4):1297–301.

Barasa KS, Wanjoya AK, Waititu AG. Analysis of determinants of antenatal care services utilization in Nairobi County using logistic regression model. Am J Theor Appl Stat. 2015;4(5):322–8.

Ahinkorah BO, Seidu A-A, Agbaglo E, Adu C, Budu E, Hagan JE, et al. Determinants of antenatal care and skilled birth attendance services utilization among childbearing women in Guinea: evidence from the 2018 Guinea Demographic and Health Survey data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):1–11.

Bala R, Singh A, Singh V, Verma P, Budhwar S, Shukla OP, et al. Impact of socio-demographic variables on antenatal services in eastern Uttar Pradesh, India. Health Care Women Int. 2021;42(4–6):580–97.

Jahnavi K, Nagaraj K, Nirgude AS. Utilization of antenatal care services in a rural area of Nalgonda district, Telangana state, India. Int J Commun Med Public Health. 2020;7(9):3380.

Anaba EA, Alor SK, Badzi CD. Utilization of antenatal care among adolescent and young mothers in Ghana; Analysis of The 2017/18 Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey. 2021.

Neupane B, Rijal S, Gc S, Basnet TB. Andersen’s model on determining the factors associated with antenatal care services in Nepal: an evidence-based analysis of Nepal demographic and health survey 2016. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:1–11.

El-Khatib Z, Kolawole Odusina E, Ghose B, Yaya S. Patterns and predictors of insufficient antenatal care utilization in nigeria over a decade: a pooled data analysis using demographic and health surveys. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):8261.

Kareem YO, Morhason-Bello IO, OlaOlorun FM, Yaya S. Temporal relationship between Women’s empowerment and utilization of antenatal care services: lessons from four National Surveys in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):1–14.

Shibre G, Zegeye B, Yeboah H, Bisjawit G, Ameyaw EK, Yaya S. Women empowerment and uptake of antenatal care services: a meta-analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys from 33 Sub-Saharan African countries. Arch Public Health. 2021;79(1):1–9.

Hossain B, Hoque AA. Women empowerment and antenatal care utilization in Bangladesh. J Dev Areas. 2015;49(2):109–24.

Sado L, Spaho A, Hotchkiss DR. The influence of women’s empowerment on maternal health care utilization: evidence from Albania. Soc Sci Med. 2014;114:169–77.

Awusi V, Anyanwu E, Okeleke V. Determinants of antenatal care services utilization in Emevor Village, Nigeria. Benin J Postgrad Med. 2009;11(1).

Bhowmik KR, Das S, Islam MA. Modelling the number of antenatal care visits in Bangladesh to determine the risk factors for reduced antenatal care attendance. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(1): e0228215.

Rizkianti A, Afifah T, Saptarini I, Rakhmadi MF. Women’s decision-making autonomy in the household and the use of maternal health services: an Indonesian case study. Midwifery. 2020;90: 102816.

Nisha MK, Alam A, Rahman A, Raynes-Greenow C. Modifiable socio-cultural beliefs and practices influencing early and adequate utilisation of antenatal care in rural Bangladesh: a qualitative study. Midwifery. 2021;93: 102881.

Wulandaria RD, Laksonob AD. Education as predictor of the knowledge of pregnancy danger signs in Rural Indonesia. Int J Innov Creativ Change. 2020;13(1).

Shamanewadi AN, Pavithra M, Madhukumar S. Level of awareness of risk factors and danger signs of pregnancy among pregnant women attending antenatal care in PHC, Nandagudi. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2020;9(9):4717.

Mwilike B, Nalwadda G, Kagawa M, Malima K, Mselle L, Horiuchi S. Knowledge of danger signs during pregnancy and subsequent healthcare seeking actions among women in Urban Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):1–8.

Sugiartini DK. The influence of pregnant women classes on knowledge, attitudes and skills of conducting early detection of danger signs during the second trimester of pregnancy in Buleleng Regency. J Qual Public Health. 2020;3(2):564–74.

Nangolo Kotriede M, Kerthu HS, Maano NE, Filippine N. Assessment of the knowledge and attitude of pregnant women regarding the benefits of antenatal care service utilization at Rundu Clinic Namibia. Int J Med Sci Health Res. 2020;4(2)

Nasir BB, Fentie AM, Adisu MK. Adherence to iron and folic acid supplementation and prevalence of anemia among pregnant women attending antenatal care clinic at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(5): e0232625.

Dewau R, Muche A, Fentaw Z, Yalew M, Bitew G, Amsalu ET, et al. Time to initiation of antenatal care and its predictors among pregnant women in Ethiopia: Cox-gamma shared frailty model. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2): e0246349.

Shrestha G. Factors related to utilization of antenatal care in Nepal: a generalized linear approach. J Kathmandu Med Coll. 2013;2(2):69–74.

Seidu A-A, Agbaglo E, Dadzie LK, Ahinkorah BO, Ameyaw EK, Tetteh JK. Individual and contextual factors associated with barriers to accessing healthcare among women in Papua New Guinea: insights from a nationwide demographic and health survey. Int Health. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihaa097.

Ahmed S, Creanga AA, Gillespie DG, Tsui AO. Economic status, education and empowerment: implications for maternal health service utilization in developing countries. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(6): e11190.

Houweling TA, Ronsmans C, Campbell OM, Kunst AE. Huge poor-rich inequalities in maternity care: an international comparative study of maternity and child care in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:745–54.

Acharya D, Khanal V, Singh JK, Adhikari M, Gautam S. Impact of mass media on the utilization of antenatal care services among women of rural community in Nepal. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(1):1–6.

Deo KK, Paudel YR, Khatri RB, Bhaskar RK, Paudel R, Mehata S, et al. Barriers to utilization of antenatal care services in Eastern Nepal. Front Public Health. 2015;3:197.

Fatema K, Lariscy JT. Mass media exposure and maternal healthcare utilization in South Asia. SSM-Popul Health. 2020;11: 100614.

Hällsten M, Thaning M. Wealth vs. education, occupation and income–unique and overlapping influences of SES in intergenerational transmissions. The Department of Sociology Working Paper Series, Stockholm University. 2018; No. 35.

Wang Z, Jetten J, Steffens NK. The more you have, the more you want? Higher social class predicts a greater desire for wealth and status. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2020;50(2):360–75.

Wu Y-T, Daskalopoulou C, Terrera GM, Niubo AS, Rodríguez-Artalejo F, Ayuso-Mateos JL, et al. Education and wealth inequalities in healthy ageing in eight harmonised cohorts in the ATHLOS consortium: a population-based study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(7):e386–94.

Siddique AB, Perkins J, Mazumder T, Haider MR, Banik G, Tahsina T, et al. Antenatal care in rural Bangladesh: gaps in adequate coverage and content. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(11): e0205149.

Okedo-Alex IN, Akamike IC, Ezeanosike OB, Uneke CJ. Determinants of antenatal care utilisation in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10): e031890.

Tizazu MA, Asefa EY, Muluneh MA, Haile AB. Utilizing a minimum of four antenatal care visits and associated factors in Debre Berhan Town, North Shewa, Amhara, Ethiopia, 2020. Risk Manag Healthcare Policy. 2020;13:2783.

Ekholuenetale M, Nzoputam CI, Barrow A, Onikan A. Women’s enlightenment and early antenatal care initiation are determining factors for the use of eight or more antenatal visits in Benin: further analysis of the Demographic and Health Survey. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2020;95:1–12.

Jiwani SS, Amouzou-Aguirre A, Carvajal L, Chou D, Keita Y, Moran AC, et al. Timing and number of antenatal care contacts in low and middle-income countries: analysis in the Countdown to 2030 priority countries. J Glob Health. 2020;10(1):010502.

Uldbjerg CS, Schramm S, Kaducu FO, Ovuga E, Sodemann M. Perceived barriers to utilization of antenatal care services in northern Uganda: a qualitative study. Sex Reprod Healthcare. 2020;23: 100464.

Alemi S, Nakamura K, Rahman M, Seino K. Male participation in antenatal care and its influence on their pregnant partners’ reproductive health care utilization: insight from the 2015 Afghanistan Demographic and Health Survey. J Biosoc Sci. 2021;53(3):436–58.

Funsani P, Jiang H, Yang X, Zimba A, Bvumbwe T, Qian X. Why pregnant women delay to initiate and utilize free antenatal care service: a qualitative study in the southern district of Mzimba, Malawi. Glob Health J. 2021;5(2):74–8.

Erasmus MO, Knight L, Dutton J. Barriers to accessing maternal health care amongst pregnant adolescents in South Africa: a qualitative study. Int J Public Health. 2020;65:469–76.

Bradley C, Millar M. Persistent stigma despite social change: experiences of stigma among single women who were pregnant or mothers in the Republic of Ireland 1996–2010. Fam Relatsh Soc. 2021;10(3):413–29(17).

Laksono AD, Rukmini R, Wulandari RD. Regional disparities in antenatal care utilization in Indonesia. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(2): e0224006.

Sarker BK, Rahman M, Rahman T, Rahman T, Khalil JJ, Hasan M, et al. Status of the WHO recommended timing and frequency of antenatal care visits in Northern Bangladesh. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(11): e0241185.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Ethiopian Central Statistical Agency for providing authorization letter to access EDHS-2019 dataset to conduct this study.

Funding

There is no specific funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MA: initiated the research concept, analyze and interpreted the data; BK, MY, BA, RD, YD: wrote the manuscript; all authors: critically revise, read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have equal participation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from Ethical Review Committee of Wollo University College of Medicine and Health Science. An authorization letter to download EDHS-2019 data set was also obtained from CSA after requesting www.measuredhs.com website. The requested data were treated strictly confidential and was used only for the study purpose. Complete information regarding the ethical issue was available in the EDHS-2019 report.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Arefaynie, M., Kefale, B., Yalew, M. et al. Number of antenatal care utilization and associated factors among pregnant women in Ethiopia: zero-inflated Poisson regression of 2019 intermediate Ethiopian Demography Health Survey. Reprod Health 19, 36 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-022-01347-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-022-01347-4