Abstract

The study aimed to identify the factors influencing the utilization of antenatal care (ANC) services among pregnant women to fulfill the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) for maternal mortality ratio (MMR) by 2030; we also investigated the consistency of these factors. We have used the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data from 29 developing countries for analysis. A binary logistic regression model was run using Demographic and Health Survey data from Bangladesh to determine the factors influencing ANC utilization in Bangladesh. In addition, a random-effects model estimation for meta-analysis was performed using DHS data from 29 developing to investigate the overall effects and consistency between covariates and the utilization of ANC services. Logistic regression revealed that residence (odds ratio [OR] 1.436; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.238, 1.666), respondent’s education (OR 3.153; 95% CI 2.204, 4.509), husband’s education (OR 2.507; 95% CI 1.922, 3.271) wealth index (OR 1.485; 95% CI 1.256, 1.756), birth order (OR 0.786; 95% CI 0.684, 0.904), working status (OR 1.292; 95% CI 1.136, 1.470), and media access (OR 1.649; 95% CI 1.434, 1.896) were the main significant factors for Bangladesh. Meta-analysis showed that residence (OR 2.041; 95% CI 1.621, 2.570), respondent’s age (OR 1.260; 95% CI 1.106, 1.435), respondent’s education level (OR 2.808; 95% CI 2.353, 3.351), husband’s education (OR 2.267; 95% CI 1.911, 2.690), wealth index (OR 2.715; 95% CI 2.199, 3.352), birth order (OR 1.722; 95% CI 1.388, 2.137), and media access (OR 2.474; 95% CI 2.102, 2.913) were the most conclusive factors in a subjects decision to attend ANC. Our results support the augmentation of maternal education and media access in rural areas with ANC services. Particular focus is needed for women from Afghanistan since they have a lower level of ANC services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Globally, maternal mortality is a significant public health problem in most developing countries [1, 2]. As a result, this is still one of the main barriers to human development. In 2005, almost half a million pregnant women died because of pregnancy complications, and 73% of these deaths were directly related to pregnancy [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that around 295,000 women of reproductive age died globally in 2017; 9.2% of these deaths were due to maternal causes (i.e., pregnancy and childbirth) [3]. A systematic review revealed that almost 99% of maternal deaths were recorded in developing countries [4]. Moreover, maternal deaths were notable in Southern Asia (20%) and sub-Saharan Africa (66%), and jointly, these two territories accounted for almost 86% of death among reproductive women in 2017 [3]. According to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the maternal mortality rate needs to be reduced to 70 for every 100,000 live births globally by 2030 [5]. In our efforts to reduce maternal mortality, antenatal care (ANC) has become an indispensable factor in the determination of maternal and neonatal mortality in any community regardless of sociodemographic context [6,7,8,9].

In order to safeguard the health of both the unborn child and the pregnant mother, ANC is the best care that one can provide to identify problems rapidly during the early period of pregnancy. Furthermore, ANC provides the opportunity to observe, identify, and treat pregnancy abnormalities with a range of health promotions and preventive care strategies [10, 11]. A pregnant woman can easily benefit from ANC services by visiting a healthcare center or trained medical personnel. ANC provides a precautionary measure for pregnancy complications and provides a range of health-related services and information which may help women to improve their health and that of their babies. During the early stages of pregnancy, most of the signs and symptoms for complications during pregnancy and childbirth can be easily identified in pregnant women with the aid of trained medical personnel [12]. When a pregnant woman first visits a healthcare center, a trained medical officer gives her an ANC record card with the first pregnancy record. Subsequently, the healthcare center also records the woman's initials/signature for future ANC consultations to identify problems such as preterm delivery and accurately oversees these complications [13]. It is essential that the first ANC visit provides a comprehensive checkup for pregnancy complications and gestational age [13].

To minimize maternal mortality, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends during eight ANC visits during the first trimester to identify abnormalities and complications in pregnancy; this involves trained medical personnel and frequent communication. By contrast, two and five visits are required in the second and third trimesters, respectively [14]. Research has also shown that standard of care during unexpected emergencies during childbirth, along with competent delivery care, can also help to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality [15].

Globally, maternal mortality decreased from 385 to 216 deaths for every 100,000 live births between 1990 and 2015 [16]. However, this reduction is not sufficient to achieve the SDGs by 2030. Existing literature shows that inadequate utilization of ANC services can approximately double maternal mortality in low- and middle-income countries [17]. A previous meta-analysis of 28 papers relating to developing countries showed that media exposure, women's employment, household income, marital status, maternal education, husband’s education, availability, cost, and the history of obstetric complications, are all factors that can influence ANC visits [18]. Since this inadequate utilization of ANC can worsen the outcome of pregnancy, it is vital that medical personnel acknowledge the factors that can influence the utilization of ANC among women in developing countries; this was the aim of the present study in which we assessed 29 different countries. The impact of influencing factors can vary for different reasons. In this study, we aimed to investigate the consistency of influencing factors across different countries by considering between-study heterogeneity. We also conducted a meta-analysis utilizing a random-effects model for 29 developing countries to identify differences in the factors that influence the utilization of ANC services by addressing heterogeneity.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Design

In the present study, we used nationally representative cross-sectional datasets from 29 developing countries. These datasets were extracted from the Demographics and Health Survey (DHS) conducted in these countries.

2.2 Data Source and Extraction

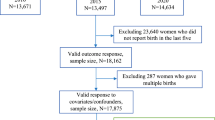

The information used in this investigation was extracted from nationally representative secondary datasets from 29 developing countries (accessed on January 2020) [19] from 2014 to 2019. The countries were as follows: Afghanistan 2015, Angola 2015–16, Bangladesh 2017–18, Benin 2017–18, Burundi 2016–17, Cameroon 2018, Chad 2014–15, Democratic Republic of the Congo 2018, Ethiopia 2016, Ghana 2014, Guinea 2018, Haiti 2016–17, India 2015–16, Indonesia 2017, Jordan 2017–18, Kenya 2014, Lesotho 2014, Malawi 2015–16, Mali 2018, Myanmar 2015–16, Nepal 2016, Nigeria 2018, Pakistan 2017–18, Rwanda 2014–15, Senegal 2019, Sierra Leone 2019, South Africa 2016, Timor-Leste 2016, and Zimbabwe 2015. This study only considered married women (15–49 years) who delivered at least one baby in the 5 years prior to the survey. Figure 1 illustrates the procedure used for data extraction.

A flow diagram demonstrating the inclusion and exclusion of data. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097. For more information, visit www.prisma-statement.org

2.3 Variables

Using existing literature, we identified the most common factors affecting ANC visits: ethnicity, residence, parity, respondent’s age, respondent’s education, husband’s education, marital status, family size, structure of the respondent’s decision on ANC utilization, the position of women in society, women's employment, household income, and media exposure [18, 20]. Our study did not include risk factors such as the history of obstetric complications, availability, accessibility, and affordability, due to missing data in the 29 selected countries.

The respondents of this study were women who had received ANC since pregnancy; therefore, the number of ANC visits was the response variable. Categorization of the response variable was generated based on the number of ANC visits recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) during pregnancy. This response variable was categorized into two groups: those who attended \(\ge\) 4 ANC visits were counted as category “yes”; otherwise, the category was “no.”

A set of socioeconomic and demographic risk factors are known to affect ANC visits during pregnancy; these were considered as explanatory variables. First, for respondent’s education, we merged primary, secondary, and higher education into an “educated” group and those with no education into a “not educated” group. For the variable wealth index, the poorest, poorer, and middle were recoded into the “up to middle” category, whereas the richer and richest formed the “rich” category. Husband’s education was recoded in a similar way to the mother’s education. The categories remained the same as found in the original dataset for the variable types of residence. In terms of media access, our recoded categories were “yes” and “no.” Finally, categories for birth order were “1st order” for mothers who had only one child while all others were categorized as “other order” (Table 1).

2.4 Random Effects Model and Meta-analysis

Sampling from unknown distributions includes effect sizes that will differ in a random effect model. The study aimed to calculate the mean and variance of the unrevealed population of effect sizes [21].

Usually, one true effect is considered, but in terms of random effects in meta-analysis, we approve a distribution of true effects sizes [22]. This is why the pooled effect cannot show this one common effect. Alternatively, this exhibits the mean of the population of actual effects. Specifically for any observed effect. That is:

Sampling in two levels2, and errors from two sources, need to be considered by the random-effects model. Firstly, θ (true effect size) is independently drawn from a distribution with mean (μ) and variance (τ2). Secondly, T (observed effect size) on condition θ are selected from the true effect size with a variance (σ2) that is generally dependent on sample size. Furthermore, sampling error from within sources (ε) and between sources (ζ) are needed to estimate μ before occupying weights.

\({I}^{2}\) reports the proportion of the observed variance and real differences in effect size. The statistic \({I}^{2}\) can be computed as

Leave-one-country-out sensitivity analysis was adopted to evaluate the stability of the findings and to examine each country's incompatible impact on meta-analysis [23]. In the multivariate models, the results were presented in the form of odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for exposures, thus controlling confounding effects within the model. We also applied sampling weight to make the entire dataset nationally representative. Statistical analysis was carried out with R version 4.0.4. A 5% alpha level was set as the statistical cut-off point (P-value < 0.05) to identify significant associations.

3 Results

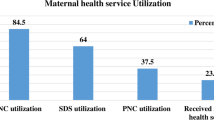

3.1 Representation of Frequency for Selected Variables from 29 Developing Countries

3.2 Binary Logistic Regression Modeling

Table 2 shows that for Bangladesh, the type of residence, respondent’s education level, husband’s education level, wealth index, birth order, respondent’s working status, and media access, were all significantly associated with the utilization of antenatal care services. The respondents who lived in urban areas were 1.436 times more likely to receive ANC services (\(\ge\) 4 visits) than respondents from rural areas (OR 1.436; 95% CI 1.238, 1.666). Educated women were more likely to receive ANC than respondents with no education. Women who received primary education at most were 1.882 times more likely to attend ANC services (\(\ge\) 4 visits) than women with no education (OR 1.882; CI 1.379, 2.568). Women who received secondary education at most were 2.736 times more likely to attend ANC services (\(\ge\) 4 visits) than women with no education (OR 2.736; CI 2.007, 3.731). Similarly, women who received higher education were 3.153 times more likely to attend ANC services than women with no education (OR 3.153; CI 2.204, 4.509). The level of the respondent’s husband’s education was another factor that influenced attendance at ANC services in Bangladesh. A respondent with a husband who received secondary education was 1.329 times more likely to attend ANC than those with an uneducated husband (OR 1.329; CI 1.071, 1.648). Similarly, respondents with a husband with higher education were 2.507 times more likely to attend ANC services than those with an uneducated husband likely (OR 2.507; CI 1.922, 3.271). A respondent from a rich family background was 1.485 times more likely to attend ANC services than those with a low-income family background (OR 1.485; CI 1.256, 1.756). A respondent with their first child were 0.786 times less likely to receive ANC services (\(\ge\) 4 visits) than a respondent with more than one child (OR 0.786; CI 0.684, 0.904). The working status of the respondent was another influencing factor the utilization of ANC services. A respondent with a working status was 1.292 times more likely to attend ANC services (\(\ge\) 4 visits) than a respondent who was not working (OR 1.292; CI 1.136, 1.470). Media access was another influencing factor influencing the utilization of ANC services. A respondent with media access was 1.649 times more likely to attend ANC services than a respondent with no media access (OR 1.649, CI 1.434, 1.896).

3.3 Random Effects Model and Meta-analysis for 29 Developing Countries

The true treatment effect can estimate the mean treatment effect, which varies from study to study according to the random-effects model. In this study, we observed high levels of heterogeneity; this is why we used the random-effects model. From Tables 3 and 4, it is evident that approximately 98.3% of the variation (I2 = 98.3%) was found for the variable, respondent’s education. The overall effect estimate for this variable had an OR of 2.808 (95% CI 2.353, 3.351), thus suggesting that educated women were 2.808 times more likely to attend at least four ANC visits than women with no education; this finding was similar to the results of the Binary Logistic Regression (BLR) model for Bangladesh. Approximately 99.0% of the variation (I2 = 99.0%) was accounted for by wealth index; the overall effect estimate had an OR of 2.715 (95% CI 2.199, 3.352), thus suggesting that women with a high wealth index were 2.715 times more likely to attend ANC services when compared to those with a lower index.

With regards to the educational level of the husband, we determined an I2 of 98.4% for the overall model. The overall effect for this variable had an OR of 2.267 (95% CI 1.911, 2.690), meaning that respondents were 2.267 times more likely to attend at least four ANC visits during pregnancy with an educated husband than if the respondent had a non-educated husband. With regards to media access, respondents with media access were 2.474 times more likely to attend at least four ANC visits than respondents with no media access (OR 2.474; 95% CI 2.102, 2.913); in the case of Bangladesh, the likelihood was 1.649 times higher. For this variable, I2 was determined to be 98.7% of the overall model. Approximately 98.9% of the variation (I2 = 98.9%) was detected for the type of residence, where the overall effect size was 2.041 (OR 2.041, 95% CI 1.621, 2.570), meaning that respondents from the urban area were 2.041 times more likely to attend at least four ANC visits than those from rural areas; the BLR model for Bangladesh indicated a similar result. With regards to birth order, I2 was 98.1% and the overall effect size was 1.722 (OR 1.722; 95% CI 1.388, 2.137). This result suggests that a respondent with their first child was 1.722 times more likely to attend at least four ANC visits than respondents with more than one child; this did not concur with the BLR model for Bangladesh. The generalized or combined effects of meta-analysis could be liable for the observed discrepancy across published documents. It is necessary to analyze data over a longer time period to fully investigate this issue. With regards to the respondent’s current age, I2 was determined to be 79.7% for the overall model. The overall effect for this variable was 1.260 (OR 1.260; 95% CI 1.106, 1.435), meaning that respondents aged more than 19 years had a 1.260-fold higher chance of attending at least four ANC visits during their pregnancies than respondents aged less than 19 years.

Figure 2 shows the effect of (a) respondent’s age and (b) respondent’s education on receiving ANC, as forest plots. Figure 3 shows the effect of (a) husband’s education and (b) wealth index on the utilization of ANC services. Figure 4 shows the impact of (a) working status and (b) media access on the utilization of ANC services, as forest plots. Figure 5 shows the effect of the (a) place of residence and (b) birth order on the utilization of ANC services as forest plots. The forest plots shown in these figures include OR and CI.

4 Discussion

In this study, we identified several risk factors for the utilization of ANC services using nationally representative datasets from 29 developing countries. Previous studies found that wealth index, maternal education, husband’s education, type of residence, media access, and birth order, all had significant impacts on the utilization of ANC services [18, 20]. Our present results corroborate thus previous research and show that maternal education, media access, and wealth index are the most significant factors associated with the utilization of ANC services.

The findings of our study show that the utilization of ANC services increased as the level of maternal education increased. This result is plausible because better education will lead women to gain better knowledge of ANC services and be more aware with regards to ANC services. Furthermore, self-independence, confident decision-making, and capability for managing household and health all increased with better educational levels [12, 24, 25]. This finding also concurs with previous studies [25,26,27,28], although one previous study contradicts our study with regards to Pakistan [29]. Husband’s education is also an essential factor, as reported by previous studies [24, 28]. In the long run, mandatory free school education from childhood can increase the levels of education country-wide.

We also found that wealth index was positively associated with the utilization of ANC services, meaning that mothers in wealthy families tended to attend more ANC services than those with middle or low incomes; these findings concur with a those of a previous study [12]. The restriction of economic resources is directly associated with poverty, thus accounting for the lower utilization of ANC services. Furthermore, pregnant women cannot afford costly facilities from the healthcare center, especially in regions where poverty is extreme [30]. A possible solution for this could be the increased provision of funding in the health sector through insurance or different organizations, especially in Afghanistan and Bangladesh.

The type of residence was also significantly related to the utilization of ANC services. Because of the reduced availability of educational services and poor economic status in rural areas, there is a lower chance of accessing ANC services in these areas than in urban areas. As with our study, rural women from Nepal were least likely to receive ANC services; these findings were corroborated by other studies [31, 32]. Mothers-in-law were also found to have a significant and vital role in the utilization of ANC by pregnant women in Nepal; therefore, promoting health and educational interventions to both the mother-in-law and husband can improve the situation [18]. Furthermore, education needs to be better linked to the utilization of maternal care and needs to be introduced to more rural areas in Nepal [33]. We also found that the number of ANC visits increase as if the respondent has access to media. Studies have shown that mass media play an essential role in expanding the practice of ANC service and other services [34, 35]. Moreover, findings from our meta-analysis indicated that birth order is related to ANC utilization; women giving birth to their first child have a higher odds of ANC utilization. Parents are usually more protective and excited for their first born than for subsequent birth orders, thus resulting in a higher chance of ANC utilization during pregnancy. This finding corresponds with those of some previous studies [36].

In the present study, we found that age was significantly associated with the utilization of ANC services; older mothers had a higher likelihood of utilizing ANC services. This agreement supports previous studies conducted in both India and Indonesia [37, 38]. It is possible that awareness and knowledge relating to ANC services are higher among women who are older [39, 40]. However, our results contrast with those of some other studies, which reported an inverse association between age and the utilization of ANC services [41]. In the present study, the BRL model for Bangladesh revealed that working women are more likely to utilize ANC services, as reported previously [42]. Working women possess greater financial capability to adopt health services during the period of gestation [42]. By contrast, there was no significant association between working status and ANC utilization in the combined effects of our meta-analysis.

While the present study has many strengths, this study also has some limitations that need to be considered. We used cross-sectional data incorporating different time points from the countries chosen for analysis. Each variable was categorized into two categories; then, we created a two-by-two cross-tabulation table, this is a known limitation associated with performing meta-analysis from cross-sectional datasets. In addition, we could not incorporate all risk factors due to some cases missing distinct variables. Moreover, the surveys incorporated in this study were all performed over different periods.

However, despite these limitations, the strength of this study is that we analyzed nationally representative datasets from 29 developing countries by applying an accurate probability sampling technique. This meta-analysis provides a precise and compact overview of the factors that determine ANC visits for developing countries, thus providing a resource that can guide policymakers for targeted interventions and resource allocation.

5 Conclusion

Undoubtedly, ANC is an indispensable factor that can reduce maternal mortality and morbidity, along with child malnutrition and mortality. Economic barriers and lack of education are significant predictors for the nonutilization of ANC services. In this study, we found that respondents from rural areas with low-income families in developing countries have lower odds of utilizing ANC; the WHO recommends \(\ge\) 4 ANC visits. Furthermore, we found that respondents with a lower level of education and those with less educated husbands, who had no access to media, had a lower chance of utilizing ANC services. These barriers can be mitigated by introducing mandatory free school education and reducing the cost of maternal healthcare services or providing special financing in the health sector via insurance or different organizations.

Data availability

The secondary DHS datasets for the 29 developing countries that were analyzed during the current study are freely available on the following website: http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm

References

Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, Tunçalp O, Moller A, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(6):e323–33.

Zere E, Suehiro Y, Arifeen A, Moonesinghe L, Chanda SK, Kirigia JM. Equity in reproductive and maternal health services in Bangladesh. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12(1):1–8.

Organization WH. Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2017: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. 2019.

Kassebaum NJ, Bertozzi-Villa A, Coggeshall MS, Shackelford KA, Steiner C, Heuton KR, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet. 2014;384(9947):980–1004.

Assembly G. United Nations: Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. UN: New York, NY, USA. 2015.

Lambon-Quayefio MP, Owoo NS. Examining the influence of antenatal care visits and skilled delivery on neonatal deaths in Ghana. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2014;12(5):511–22.

Singh A, Pallikadavath S, Ram F, Alagarajan M. Do antenatal care interventions improve neonatal survival in India? Health Policy Plan. 2014;29(7):842–8.

Wehby GL, Murray JC, Castilla EE, Lopez-Camelo JS, Ohsfeldt RL. Prenatal care effectiveness and utilization in Brazil. Health Policy Plan. 2009;24(3):175–88.

Garrido GG. The impact of adequate prenatal care in a developing country: testing the WHO recommendations. UCLA CCPR Population Working Papers. 2009.

Gross K, Alba S, Glass TR, Schellenberg JA, Obrist B. Timing of antenatal care for adolescent and adult pregnant women in south-eastern Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2012;12(1):1–12.

Kisuule I, Kaye DK, Najjuka F, Ssematimba SK, Arinda A, Nakitende G, et al. Timing and reasons for coming late for the first antenatal care visit by pregnant women at Mulago hospital Kampala Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbi. 2013;13(1):1–7.

AbouZahr C, Wardlaw T. Antenatal care in developing countries: promises, achievements and missed opportunities–an analysis of trends, levels and differentials, 1990–2001. Antenatal care in developing countries: promises, achievements and missed opportunities-an analysis of trends, levels and differentials, 1990–20012003. p. 32.

Finlayson K, Downe S. Why do women not use antenatal services in low-and middle-income countries? A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. PLoS Med. 2013;10(1): e1001373.

Organization WH. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. World Health Organization; 2016.

Pell C, Meñaca A, Were F, Afrah N, Chatio S, Manda-Taylor L, Hamel MJ, Hodgson A, Tagbor H, Kalilani L, Ouma P, Pool R. Factors affecting antenatal care attendance: results from qualitative studies in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e53747.

Alkema L, Chou D, Hogan D, Zhang S, Moller A-B, Gemmill A, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group. The Lancet. 2016;387(10017):462–74.

Bauserman M, Lokangaka A, Thorsten V, Tshefu A, Goudar SS, Esamai F, et al. Risk factors for maternal death and trends in maternal mortality in low-and middle-income countries: a prospective longitudinal cohort analysis. Reprod Health. 2015;12(2):1–9.

Labarrere CA, Woods J, Hardin J, Campana G, Ortiz M, Jaeger B, et al. Early prediction of cardiac allograft vasculopathy and heart transplant failure. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(3):528–35.

World Bank. Countries and Economies 2019. https://data.worldbank.org/country. Accessed 8 Oct 2021

Ye Y, Yoshida Y, Harun-Or-Rashid M, Sakamoto J, Sakamoto J. Factors affecting the utilization of antenatal care services among women in Kham district, Xiengkhouang province, Lao PDR Nagoya. J Med Sci. 2010;72(1–2):23–33.

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth methods. 2010;1(2):97–111.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88.

Normand SLT. Meta-analysis: formulating, evaluating, combining, and reporting. Stat Med. 1999;18(3):321–59.

Prusty RK, Buoy S, Kumar P, Pradhan MR. Factors associated with utilization of antenatal care services in Cambodia. J Public Health. 2015;23(5):297–310.

Furuta M, Salway S. Women’s position within the household as a determinant of maternal health care use in Nepal. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2006;32:17–27.

Kamal SM. Socioeconomic factors associated with contraceptive use and method choice in urban slums of Bangladesh. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2015;27(2):NP2661–3276.

Maraga S, Namosha E, Gouda H, Vallely L, Rare L, Phuanukoonnon S. Sociodemographic factors associated with maternal health care utilization in Wosera, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea. P N G Med J. 2011;54(3/4):154.

Tey N-P, Lai S-l. Correlates of and barriers to the utilization of health services for delivery in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Sci World J. 2013;2013:423403. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/423403

Nisar N, White F. Factors affecting utilization of antenatal care among reproductive age group women (15–49 years) in an urban squatter settlement of Karachi. J Pak Med Assoc. 2003;53(2):47.

Agha S, Carton TW. Determinants of institutional delivery in rural Jhang, Pakistan. Int J Equity Health. 2011;10(1):1–12.

Naing D, Anderios F, Lin Z. International Journal of Collaborative Research on Internal Medicine & Public Health: Geographic and Ethnic Distribution of P Knowlesi Infection in Sabah, Malaysia. Borneo Res Bull. 2011;42:368.

Paudel YR, Jha T, Mehata S. Timing of first antenatal care (ANC) and inequalities in early initiation of ANC in Nepal. Front Public Health. 2017;5:242.

Mullany BC, Becker S, Hindin M. The impact of including husbands in antenatal health education services on maternal health practices in urban Nepal: results from a randomized controlled trial. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(2):166–76.

Acharya D, Khanal V, Singh JK, Adhikari M, Gautam S. Impact of mass media on the utilization of antenatal care services among women of rural community in Nepal. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(1):1–6.

Geta MB, Yallew WW. Early initiation of antenatal care and factors associated with early antenatal care initiation at health facilities in southern Ethiopia. Adv Public Health. 2017;2017:1624245. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/1624245

Chenga D, Schwarzb E, Douglasb E, Horona I. Unintended pregnancy and associated maternal preconception, prenatal and postpartum behaviours. Contraception. 2009;79:194–8.

Roy MP, Mohan U, Singh SK, Singh VK, Srivastava AK. Determinants of utilization of antenatal care services in rural Lucknow, India. J Family Med Primary Care. 2013;2(1):55.

Efendi F, Chen C-M, Kurniati A, Berliana SM. Determinants of utilization of antenatal care services among adolescent girls and young women in Indonesia. Women Health. 2017;57(5):614–29.

Fatmi Z, Avan BI. Demographic, socio-economic and environmental determinants of utilisation of antenatal care in a rural setting of Sindh, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2002;52(4):138.

Bassani DG, Surkan PJ, Olinto MTA. Inadequate use of prenatal services among Brazilian women: the role of maternal characteristics. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009;35:15–20.

Nketiah-Amponsah E, Senadza B, Arthur E. Determinants of utilization of antenatal care services in developing countries: recent evidence from Ghana. Afr J Econ Manag Stud. 2013;4:58–73.

Adewuyi EO, Auta A, Khanal V, Bamidele OD, Akuoko CP, Adefemi K, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with underutilization of antenatal care services in Nigeria: a comparative study of rural and urban residences based on the 2013 Nigeria demographic and health survey. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(5): e0197324.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT) Bangladesh and MEASURE DHS for allowing us to use DHS data from 29 developing countries for our analysis.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Md.AI conceived this study and contributed to data analysis, interpretation, and manuscript writing. NJS contributed to manuscript writing and revision. HMA and JN contributed to data editing, manuscript writing and revision. ZAB was responsible for major editing and critical revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Islam, M.A., Sathi, N.J., Abdullah, H.M. et al. Factors Affecting the Utilization of Antenatal Care Services During Pregnancy in Bangladesh and 28 Other Low- and Middle-income Countries: A Meta-analysis of Demographic and Health Survey Data. Dr. Sulaiman Al Habib Med J 4, 19–31 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44229-022-00001-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44229-022-00001-2