Abstract

Background

Clinical phenotypes and outcomes in juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) have been defined by various myositis-specific autoantibodies (MSAs). One of the recently described MSAs associated with DM is targeted against the small ubiquitin-like modifier 1 activating enzyme (SAE). We report an anti-SAE autoantibody-positive JDM patient complicated with interstitial lung disease (ILD).

Case presentation

An 8-year-8-month-old Japanese girl presented with bilateral eyelid edema and facial erythema. At 8 years 4 months, she had dry cough and papules with erythema on the dorsal side of the interphalangeal joints of both hands. Her facial erythema gradually worsened and did not improve with topical steroids. At the first visit to our department at 8 years 8 months of age, she had a typical heliotrope rash and Gottron’s papules, with no fever or weight loss, and a chest computed tomography scan showed ground-glass opacity under visceral pleura. There was no clinical evidence of myositis, muscle weakness, myalgia, or muscle magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings. She had mild dry cough, without any signs of respiratory distress. Laboratory tests showed no elevated inflammatory markers. She had a normal serum creatine kinase level with a slightly elevated aldolase level, and serum anti-SAE autoantibody was detected by immunoprecipitation—western blotting. She was diagnosed with juvenile amyopathic DM complicated by ILD and received two courses of methylprednisolone pulse therapy followed by oral corticosteroid and cyclosporin A. We gradually reduced the corticosteroid dose as her skin rash improved after treatment initiation. There was no progression of muscle symptoms, dysphagia, or disease flare during a 24-month follow-up period.

Conclusions

We report a patient with anti-SAE autoantibody-positive JDM complicated by interstitial pneumonia. This patient had no progression of muscle symptoms and dysphagia during a 24-month follow-up period, which differs from previous reports in adult patients with MSAs. There have been no previous reports of pediatric patients with SAE presenting with ILD. However, ILD seen in this case was not rapidly progressive and did not require cytotoxic agents. To prevent overtreatment, appropriate treatment choices are required considering the type of ILD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Clinical phenotypes and outcomes in juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) have been defined by various myositis-specific autoantibodies (MSAs) [1, 2]. One of the recently described MSAs associated with dermatomyositis (DM) is targeted against small ubiquitin-like modifier 1 (SUMO-1) activating enzyme (SAE) [3]. Anti-SAE autoantibody-positive myositis patients have been reported in Caucasian (6–8%) and Asian adults (1–3%) [3,4,5,6,7,8] and are associated with severe cutaneous disease, progressive muscle disease with dysphagia, fever, and weight loss [9, 10]. It has also been reported that anti-SAE autoantibody-positive patients were at a lower frequency in the juvenile population (< 1%) [11, 12]. It is rare in children, with the details of its clinical course often unknown. We report an anti-SAE autoantibody-positive JDM patient with interstitial lung disease (ILD).

Case presentation

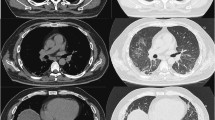

The patient, an 8-year-8-month-old Japanese girl, first manifested bilateral eyelid edema at 8 years 0 months and facial erythema 2 months later. At 8 years 4 months, she had dry cough and papules with erythema on the dorsal side of the interphalangeal joints of both hands. Her facial erythema gradually worsened and did not improve with topical steroids. She was referred to our department at 8 years and 8 months because of positive antinuclear antibodies and a chest computed tomography (CT) scan showing ground-glass opacity under the visceral pleura (Fig. 1a). At the first visit to our department, she had a typical heliotrope rash and Gottron’s papules (Fig. 2), with no fever or weight loss. Her childhood myositis assessment scale (CMAS) score was normal (51/52) and there was no clinical evidence of myositis, muscle weakness, or myalgia. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), including T2 weighted image (T2WI) and short TI inversion recovery (STIR), of the lower extremities showed normal findings without any muscle edema or myositis. An electrocardiogram and an echocardiogram showed no abnormalities. She had mild dry cough, without signs of respiratory distress, including decreased oxygen saturation. Laboratory tests showed no elevation of inflammatory markers (Table 1). Although her serum creatine kinase (CK) level was normal (91 IU/L, upper limit of normal < 163), her aldolase level was slightly elevated (9.9 U/L, upper limit of normal < 6.1). Serum Krebs von den Lungen-6 (KL-6) level was mildly elevated, serum ferritin level was normal. Anti-P155/140 (transcriptional intermediary factor-1: TIF1), anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5), anti-Mi-2, and anti-aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (ARS) including anti-Jo1autoantibodies were all negative in the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays commercially available in Japan. And also anti-nuclear matrix protein 2 (NXP2) (MJ) autoantibody was negative in the immunoprecipitation- Western Blotting. Serum anti-SAE autoantibodies were detected using immunoprecipitation—western blotting (Fig. 3) [4, 13]. The details of the methods are shown in Supplemental File.

Chest computed tomography (CT) findings. a A ground-glass opacity was observed in the left segment 6 under the visceral pleura before treatment. The arrow shows the ground-glass opacity. b Ground-glass opacity was slightly improved but not progressive 18 months after treatment initiation. The arrow shows the ground-glass opacity

Immunoprecipitation-Western blotting of anti-SAE autoantibody. Lane1: molecular weight marker, lane2: serum from the patient, lane3: positive control (serum with anti-small ubiquitin-like modifier 1 activating enzyme (SAE) autoantibody), lane4–6: negative controls (anti-transcriptional intermediary factor-1 (TIF1) gamma autoantibody; Lane4, anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) autoantibody; Lane5, anti-nuclear matrix protein 2(NXP2) autoantibody; Lane6)

The patient met the 2017 American college of rheumatology/European league against rheumatism classification criteria for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies [14] and was diagnosed with juvenile amyopathic DM complicated by ILD. She received two courses of methylprednisolone pulse therapy followed by oral corticosteroid (20 mg/day, 0.7 mg/kg/day) and cyclosporin A (150 mg/day, 5 mg/kg/day) administration. We gradually reduced the corticosteroid dose as her skin rash improved after treatment initiation. There were no new muscle symptoms, dysphagia, calcinosis, arthralgia, joint contractors, lipodystrophy, lipoatrophy, or periungual capillary changes during the follow-up period. There was no exacerbation of abnormal findings on chest CT scan (Fig. 1b) at 18 months from initial treatment, and no increase in serum KL-6 levels during follow-up. There was no flare of disease by the age of 10 years and 7 months, which was 24 months after treatment initiation. The patient continues to be prescribed oral corticosteroid (4 mg/day, 0.1 mg/kg/day) and cyclosporin A (50 mg/day, 1.25 mg/kg/day) at 24 months after treatment initiation.

Discussion and conclusions

Most JDM patients have MSAs alone or those associated with specific clinical phenotypes [1, 2]. Although several phenotypic features are similar in both adult and juvenile MSA patients, some important differences exist [15]. For example, the association of an increased risk of malignancy with anti-p155/140 (TIF1) autoantibody is significant in the adults, whereas the association has not been shown in children [1, 16]. The frequency of each MSA differs between adult DM and JDM patients. Anti-synthetase autoantibodies are positive in 20–30% of adults and are less than 5% in juveniles [2, 15]. On the other hand, anti-NXP2 (MJ) autoantibody is rare in adult patients, while it is positive in 20–25% of juveniles [2], which is the second most frequent MSA in JDM. There are also differences in the rate of MSAs positivity between races. Anti-MDA5 autoantibodies are more common in the Asian population, and anti-SRP autoantibodies are seen primarily in the African American teenage girls [17, 18]. Although the same MSAs are present, the prevalence can vary by age and race, and identifying the clinical characteristics of children with MSAs is crucial to estimate prognosis and other aspects of the disease.

Anti-SAE autoantibody is the recently identified MSA first reported in 2007 by Betteridge et al. [19]. The target autoantigens are the SUMO-1 activating enzyme heterodimer consisting of 40 kDa SAE1 and 90 kDa SAE2 [3, 19]. The frequency of anti-SAE autoantibodies positivity in adult DM patients has been reported to be 5.5–8% in the European cohorts and 1.5–3.0% in the Asians [3,4,5,6,7,8]. The clinical presentation at the onset of the illness was characterized by severe cutaneous symptoms and mild myopathic symptoms. During follow-up, patients showed the progression of myositis, dysphagia, and systemic symptoms, such as fever, weight loss, and increased inflammatory markers [3, 4, 7, 13]. In addition, a study on Asian adults showed complications of interstitial pneumonia [4, 13, 20, 21]. The frequency of ILD in the Asian adult cohort was higher than that in the Western cohort [22]. And their ILD was reported not a rapidly progressive type [4, 13, 20].

Few pediatric cases with anti-SAE antibody have been reported to date, with less than 1% of the juvenile myositis cohort. Only 3 patients (0.7%) had anti-SAE autoantibodies among 379 juvenile myositis patients in the United Kingdom (UK) cohort [11]. Of the three patients, two presented with typical rash and limited or no muscle involvement but subsequently developed weakness and raised muscle enzymes. Skin diseases were persistent in both patients. In contrast, the third patient presented with seven-month history of myalgia and weakness with no rash. Myositis was diagnosed based on elevated muscle enzymes with consistent MRI and muscle biopsy findings. This patient developed typical cutaneous features of JDM 2 years later [11].

Our patient showed typical cutaneous findings of JDM, no muscle weakness, and ILD. Although typical cutaneous symptoms have been previously reported in juvenile patients with anti-SAE autoantibodies, no juvenile patients with ILD have been reported. Our patient had non-rapidly progressive (RP) type ILD, similar to the adult Japanese patients with this autoantibody [4, 13, 20]. We have shown that the Asian patients with anti-SAE autoantibodies could have ILD, even in juvenile patients. There have been few reports of pediatric patients from Asia. An association between anti-SAE autoantibody and HLA-DRB1*04-DQA1*03-DQB1*03 haplotype in adult patients with DM has been reported [3], possibly as one of the reasons for the racial differences in phenotype and frequency of these MSA-positive patients. Although the patient had no dysphagia during the 24-month follow-up, other symptoms were similar to those reported in adults, and therefore, we must be cautious about whether muscle weakness or dysphagia will occur in this patient in the near future.

In the Japanese patients, the frequency of anti-MDA5 autoantibody-positive patients is even higher in JDM patients [23]. Adult DM or JDM with anti-MDA5 autoantibody-positive patients are often complicated with ILD, which usually shows an RP type with poor prognosis [18, 23]. Therefore, combination therapy using three immunosuppressive agents, including corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and cyclophosphamide, is recommended from the early stage of illness for adult DM patients with ILD [24]. When a patient is complicated with ILD, we tend to opt for potent immunosuppressive therapy to improve the prognosis. However, depending on the differences in MSAs, the ILD may not show the RP type, as observed in this patient with anti-SAE autoantibody. Prognostic factors for RP-ILD include positive anti-MDA5 autoantibody, the deterioration of CT findings on a weekly basis, and elevated serum ferritin, KL-6, and IL-18 levels [18, 25]. For patients complicated with ILD without these prognostic factors, the possibility of non-RP-ILD should be considered along with the possibility that combination therapy of immunosuppressive agents may be over-treating these patients. As in our patient, JDM patients with ILD should be carefully evaluated before making appropriate treatment choices.

The precise role in disease pathogenesis or the difference in the frequency between adults and children of this autoantibody are not well understood. However, usually, patients with a specific MSAs are relatively homogeneous in clinical manifestations, response to therapy, and prognosis. This case report might help the better understandings of the clinical course or prognosis of this anti-SAE autoantibody positive patients and further studies are required to understand well in this autoantibody.”

We report a patient with anti-SAE autoantibody-positive JDM complicated by ILD. The patient had no progression of muscle symptoms and dysphagia during a 24-month follow-up period, which differs from the previous reports in adult patients with MSA. There have been no previous reports of pediatric patients complicated with ILD. However, ILD identified in our patient was not a RP type and did not require a cytotoxic agent. Further studies are needed to determine the characteristics of the clinical course in pediatric patients with anti-SAE autoantibodies.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ACR:

-

American college of rheumatology

- ANA:

-

Antinuclear antibodies

- CK:

-

Creatine kinase

- CMAS:

-

Childhood myositis assessment scale

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- DM:

-

Dermatomyositis

- EULAR:

-

European league against rheumatism

- HLA:

-

Human leukocyte antigen

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- ILD:

-

Interstitial lung disease

- JDM:

-

Juvenile dermatomyositis

- KL-6:

-

Krebs von den Lungen-6

- MDA5:

-

Melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MSAs:

-

Myositis-specific autoantibodies

- NXP2:

-

Nuclear matrix protein 2

- RP:

-

Rapidly progressive

- SAE:

-

Small ubiquitin-like modifier 1 activating enzyme

- SRP:

-

Signal recognition particle

- SUMO-1:

-

Small ubiquitin-like modifier 1

- TIF1:

-

Transcriptional intermediary factor 1

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

References

Rider LG, Shah M, Mamyrova G, Huber AM, Rice MM, Targoff IN, Miller FW, Childhood Myositis Heterogeneity Collaborative Study Group. The myositis autoantibody phenotypes of the juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Medicine. 2013;92(4):223–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0b013e31829d08f9.

Rider LG, Nistala K. The juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: pathogenesis, clinical and autoantibody phenotypes, and outcomes. J Intern Med. 2016;280(1):24–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12444.

Betteridge ZE, Gunawardena H, Chinoy H, North J, Ollier WE, Cooper RG, et al. Clinical and human leucocyte antigen class II haplotype associations of autoantibodies to small ubiquitin-like modifier enzyme, a dermatomyositis-specific autoantigen target, in UK Caucasian adult-onset myositis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(10):1621–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2008.097162.

Fujimoto M, Matsushita T, Hamaguchi Y, Kaji K, Asano Y, Ogawa F, Yamaoka T, Fujikawa K, Tsukada T, Sato K, Echigo T, Hasegawa M, Takehara K. Autoantibodies to small ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzymes in Japanese patients with dermatomyositis: comparison with a UK Caucasian cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(1):151–3. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201736.

Muro Y, Sugiura K, Akiyama M. Low prevalence of anti-small ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme antibodies in dermatomyositis patients. Autoimmunity. 2013;46(4):279–84. https://doi.org/10.3109/08916934.2012.755958.

Tarricone E, Ghirardello A, Rampudda M, Bassi N, Punzi L, Doria A. Anti-SAE antibodies in autoimmune myositis: identification by unlabelled protein immunoprecipitation in an Italian patient cohort. J Immunol Methods. 2012;384(1–2):128–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jim.2012.07.019.

Bodoki L, Nagy-Vincze M, Griger Z, Betteridge Z, Szollosi L, Danko K. Four dermatomyositis-specific autoantibodies-anti-TIF1gamma, anti-NXP2, anti-SAE and anti-MDA5-in adult and juvenile patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies in a Hungarian cohort. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(12):1211–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2014.08.011.

Ge Y, Lu X, Shu X, Peng Q, Wang G. Clinical characteristics of anti-SAE antibodies in Chinese patients with dermatomyositis in comparison with different patient cohorts. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):188. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-00240-6.

Betteridge Z, McHugh N. Myositis-specific autoantibodies: an important tool to support diagnosis of myositis. J Intern Med. 2016;280(1):8–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12451.

DeWane ME, Waldman R, Lu J. Dermatomyositis: clinical features and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(2):267–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2019.06.1309.

Tansley SL, Simou S, Shaddick G, Betteridge ZE, Almeida B, Gunawardena H, Thomson W, Beresford MW, Midgley A, Muntoni F, Wedderburn LR, McHugh NJ. Autoantibodies in juvenile-onset myositis: their diagnostic value and associated clinical phenotype in a large UK cohort. J Autoimmun. 2017;84:55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2017.06.007.

Deakin CT, Yasin SA, Simou S, Arnold KA, Tansley SL, Betteridge ZE, McHugh NJ, Varsani H, Holton JL, Jacques TS, Pilkington CA, Nistala K, Wedderburn LR, on behalf of the UK Juvenile Dermatomyositis Research Group. Muscle biopsy findings in combination with myositis-specific autoantibodies aid prediction of outcomes in juvenile Dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(11):2806–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.39753.

Inoue S, Okiyama N, Shobo M, Motegi S, Hirano H, Nakagawa Y, Saito A, Nakamura Y, Ishitsuka Y, Fujisawa Y, Watanabe R, Fujimoto M. Diffuse erythema with 'angel wings' sign in Japanese patients with anti-small ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme antibody-associated dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179(6):1414–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.17026.

Lundberg IE, Tjarnlund A, Bottai M, Werth VP, Pilkington C, Visser M, et al. 2017 European league against rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and their major subgroups. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(12):1955–64. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211468.

Shah M, Mamyrova G, Targoff IN, Huber AM, Malley JD, Rice MM, Miller FW, Rider LG, with the Childhood Myositis Heterogeneity Collaborative Study Group. The clinical phenotypes of the juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Medicine. 2013;92(1):25–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0b013e31827f264d.

Targoff IN, Mamyrova G, Trieu EP, Perurena O, Koneru B, O'Hanlon TP, Miller FW, Rider LG, Childhood Myositis Heterogeneity Study Group, International Myositis Collaborative Study Group. A novel autoantibody to a 155-kd protein is associated with dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(11):3682–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.22164.

Rouster-Stevens KA, Pachman LM. Autoantibody to signal recognition particle in African American girls with juvenile polymyositis. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(5):927–9.

Kobayashi N, Takezaki S, Kobayashi I, Iwata N, Mori M, Nagai K, Nakano N, Miyoshi M, Kinjo N, Murata T, Masunaga K, Umebayashi H, Imagawa T, Agematsu K, Sato S, Kuwana M, Yamada M, Takei S, Yokota S, Koike K, Ariga T. Clinical and laboratory features of fatal rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease associated with juvenile dermatomyositis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54(5):784–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keu385.

Betteridge Z, Gunawardena H, North J, Slinn J, McHugh N. Identification of a novel autoantibody directed against small ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme in dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(9):3132–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.22862.

Gono T, Tanino Y, Nishikawa A, Kawamata T, Hirai K, Okazaki Y, Shibata Y, Kuwana M. Two cases with autoantibodies to small ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme: a potential unique subset of dermatomyositis-associated interstitial lung disease. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019;22(8):1582–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.13593.

Ansari G, Khan A, Mahto A, Pakozdi A. 125 A case of anti-SAE amyopathic dermatomyositis. Rheumatology. 2019;58(Supplement_3):kez108–033.

Jia E, Wei J, Geng H, Qiu X, Xie J, Xiao Y, Zhong L, Xiao M, Zhang Y, Jiang Y, Zhang J. Diffuse pruritic erythema as a clinical manifestation in anti-SAE antibody-associated dermatomyositis: a case report and literature review. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38(8):2189–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04562-w.

Kobayashi I, Okura Y, Yamada M, Kawamura N, Kuwana M, Ariga T. Anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody is a diagnostic and predictive marker for interstitial lung diseases associated with juvenile dermatomyositis. J Pediatr. 2011;158(4):675–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.11.033.

Nakashima R, Hosono Y, Mimori T. Clinical significance and new detection system of autoantibodies in myositis with interstitial lung disease. Lupus. 2016;25(8):925–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203316651748.

Gono T, Sato S, Kawaguchi Y, Kuwana M, Hanaoka M, Katsumata Y, Takagi K, Baba S, Okamoto Y, Ota Y, Yamanaka H. Anti-MDA5 antibody, ferritin and IL-18 are useful for the evaluation of response to treatment in interstitial lung disease with anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51(9):1563–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kes102.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Toru Igarashi (Nippon Medical School) for referring this patient to us. We also would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Funding

No funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TK planned and carried out the patients’ treatment, and wrote the manuscript. YT, KM and TM planned and carried out the patients’ treatment and helped draft the manuscript. NO and YI performed the autoantibody examination and contributed critical revisions of the manuscript. MH contributed critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content. SN participated in the patients’ treatment and contributed critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The report was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent was obtained from the patient. The IRB/Ethics Committee ruled that an approval was not required for publishing this case report.

Consent for publication

Publication consent was obtained from the patient and her guardian.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kishi, T., Tani, Y., Okiyama, N. et al. Anti-SAE autoantibody-positive Japanese patient with juvenile dermatomyositis complicated with interstitial lung disease - a case report. Pediatr Rheumatol 19, 34 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-021-00532-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-021-00532-2