Abstract

Background

Renal interstitial fibrosis (RIF) is a progressive, irreversible terminal kidney disease with a poor prognosis and high mortality. Angiopoietin-like 4 (ANGPTL4) is known to be associated with fibrosis in various organs, but its impact on the RIF process remains unclear. This study aimed to elucidate the role and underlying mechanisms of ANGPTL4 in the progression of RIF.

Methods

In vivo, a chronic kidney disease (CKD) rat model of renal interstitial fibrosis was established via intragastric administration of adenine at different time points (4 and 6 weeks). Blood and urine samples were collected to assess renal function and 24-h urinary protein levels. Kidney tissues were subjected to HE and Masson staining for pathological observation. Immunohistochemistry and real-time quantitative PCR (qRT‒PCR) were performed to evaluate the expression of ANGPTL4 and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), followed by Pearson correlation analysis. Subsequently, kidney biopsy tissues from 11 CKD patients (6 with RIF and 5 without RIF) were subjected to immunohistochemical staining to validate the expression of ANGPTL4. In vitro, a fibrosis model of human renal tubular epithelial cells (HK2) was established through hypoxic stimulation. Subsequently, an HIF-1α inhibitor (2-MeOE2) was used, and ANGPTL4 was manipulated using siRNA or plasmid overexpression. Changes in ANGPTL4 and fibrosis markers were analyzed through Western blotting, qRT‒PCR, and immunofluorescence.

Results

ANGPTL4 was significantly upregulated in the CKD rat model and was significantly positively correlated with renal injury markers, the fibrotic area, and HIF-1α. These results were confirmed by clinical samples, which showed a significant increase in the expression level of ANGPTL4 in CKD patients with RIF, which was positively correlated with HIF-1α. Further in vitro studies indicated that the expression of ANGPTL4 is regulated by HIF-1α, which in turn is subject to negative feedback regulation by ANGPTL4. Moreover, modulation of ANGPTL4 expression influences the progression of fibrosis in HK2 cells.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that ANGPTL4 is a key regulatory factor in renal fibrosis, forming a loop with HIF-1α, potentially serving as a novel therapeutic target for RIF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has emerged as a significant public health concern worldwide, impacting 10–14% of the world's population [1, 2]. Renal interstitial fibrosis (RIF) represents the shared pathological alterations and pathways leading to the terminal stage of CKD progression [3]. The pathogenic mechanisms underlying RIF primarily involve hypoxia, inflammation, myofibroblast proliferation, epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition, hemodynamic alterations, and energy metabolism changes. It constitutes a complex process involving diverse cellular elements, cytokines, and signaling pathways [4]. Currently, the etiology of RIF in CKD is intricate and has not been fully elucidated, and no effective preventive or therapeutic measures have been established. Consequently, elucidating the mechanisms governing the onset and progression of CKD-associated RIF, identifying novel targets, and developing innovative therapeutic modalities are highly important.

Angiopoietin-like 4 (ANGPTL4) belongs to the secreted protein superfamily of angiopoietin-like proteins. Structurally similar to angiopoietins, it does not bind to angiopoietin receptors but is typically considered an orphan ligand [8]. The primary structural elements of ANGPTL4 include the N-terminal signal peptide, N-terminal helical domain, connecting region, and C-terminal fibrinogen-like domain [9]. Functionally, ANGPTL4 plays a critical role in processes such as lipid metabolism, redox regulation, inflammation, angiogenesis, the hypoxic response, tissue damage repair, and tumor initiation and metastasis [10]. Its breadth of influence is intricately linked to its complex protein architecture. Currently, ANGPTL4 as a novel focal point for prognostic or predictive biomarkers across various malignancies and a burgeoning target in the realm of cancer therapies. For instance, recent studies have revealed that increased ANGPTL4 expression is closely associated with the invasiveness and drug resistance of KRASG12D pancreatic cancer [5, 6], and researchers have explored the mechanisms of drug resistance in KRAS-mutant cancers [7]. These findings may provide crucial molecular targets for new therapeutic strategies against KRAS-driven cancers.

Hypoxia is one of the pivotal events leading to RIF, and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) has emerged as the principal regulatory factor orchestrating the adaptive response to hypoxia in renal diseases [11, 12]. Previous investigations have elucidated the role of HIF-1α as an activator of ANGPTL4 [13], and HIF-1α promotes the progression of RIF [14,15,16]. However, the correlation between HIF-1α and ANGPTL4 in the context of CKD remains uncertain.

Recent studies have reported a close association between ANGPTL4 and pulmonary and hepatic fibrosis [17,18,19], potentially through mediating fibrogenesis through mechanisms such as inflammatory responses, excessive tissue repair, vascular genesis, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition [18]. Despite these findings, limited research has explored the role of ANGPTL4 in RIF. Our previous research preliminarily revealed the upregulation of ANGPTL4 expression in a CKD rat model [20]. However, substantive experimental validation is lacking.

Therefore, in this study, we investigated the role of ANGPTL4 in the pathogenesis of RIF by establishing in vivo and in vitro renal fibrosis models complemented by validation in human fibrotic kidney tissues.

Methods

Animal models

Male Sprague‒Dawley rats weighing between 170 and 180 g and aged 7 weeks were procured and maintained at the Animal Research Center of Southwest Medical University. The animals were acclimatized for one week prior to the experiment. Subsequently, the rats were randomly divided into a control group (n = 10) and a CKD group (n = 14). The CKD group was administered 2.5% adenine (Sigma‒Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) via gavage at a dosage of 250 mg/kg [21]. The treatments were administered daily for the first 4 weeks and every other day from the 5th to the 6th week. The control group received an equivalent volume of physiological saline via gavage at the same time points. At the end of the 4th and 6th weeks postadministration, five rats from each group were randomly selected. After 24-h urine samples were collected using metabolic cages, the animals were euthanized, and kidney tissues and serum samples were collected. The “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” published by the National Institutes of Health in the United States served as the basis for the animal experimental protocol, which received approval from the Animal Ethics Committee of Southwest Medical University (SWMU20210397).

Patients and samples

This study included a total of 11 patients with CKD who underwent renal biopsy at the Department of Nephrology, the Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University, from January 2022 to December 2022. Based on the pathological findings from renal biopsies, the patients were stratified into the RIF group (n = 6) and the non-RIF group (n = 5). Among the 6 patients in the RIF group, 2 presented with focal proliferative sclerosing IgA nephropathy, 2 with mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis, 1 with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and 1 with membranous nephropathy. The non-RIF group comprised 5 patients with minimal change disease. Renal tissue specimens were collected with the informed consent of the patients, and the study was approved by the Clinical Trial Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University.

Cell culture

Professor Caiwei Qiu from the Affiliated Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital of Southwest Medical University provided HK2 cells, which were cultured in DMEM/F-12 (C11330500BT, Gibco, Gaithersburg, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (C04001, VivaCell, Shanghai, China). The cultivation conditions involved a carbon dioxide incubator set at 37 °C, 5% CO2, and 95% humidity, and the culture medium was changed every 2–3 days. Subsequently, the HK2 cells were incubated with 150 μmol/L Cocl2 (C805746; Macklin, Shanghai, China) for 24 h to induce cellular fibrosis [22]. To test this possibility, the HIF-1α inhibitor 2-MeOE2 (5 μmol/L) (S1233, Selleck, Texas, USA) [23], ANGPTL4 small interfering RNA (siRNA), and overexpression plasmids (He Yuan Biotech, Shanghai, China) were used. The impact of these interventions on fibrosis in HK2 cells was then observed.

Biochemical indices and renal histopathology

Serum creatinine (Scr), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and 24-h urinary protein (24 h-Upro) levels were quantified using a fully automated biochemical analyzer (Sigma Chemical, Louis, Missouri, USA). Following established protocols, renal tissues were embedded in paraffin and subsequently processed into paraffin Sects. (4 μm). According to the respective instruction manuals, the kidney sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and baked at 65 °C before being subjected to staining procedures using a hematoxylin–eosin (HE) staining kit (C0105S, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and a Masson trichrome staining kit (BA4079A, BASO, Zhuhai, China). Finally, morphological alterations in renal tissue and the extent of blue collagen fiber deposition were observed under a microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunohistochemical staining

After deparaffinization and hydration, paraffin sections of renal tissue were subjected to antigen retrieval in Trisodium citrate buffer. Subsequent to the blockade of endogenous peroxidases, the sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with antibodies targeting HIF-1α (1:100, 36,169, CST), ANGPTL4 (1:100, DF6751, Affinity), α-SMA (1:100, 19245S, CST), and Col-I (1:100, BA0325, Wuhan Boster). The following day, the sections were incubated at 37 °C with secondary antibodies (Zhongshan Golden Bridge, Beijing, China) for 20 min, followed by DAB chromogenic staining, hematoxylin nuclear counterstaining, dehydration, and slide mounting. Finally, observation and capture were performed using a microscope, and semiquantitative analysis was conducted using IPP 6.0 software.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT–PCR)

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent, reverse transcribed into cDNA, and ultimately mixed with SYBR Green (all obtained from Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China). qRT‒PCR analysis was subsequently conducted on a LightCycler 480 II real-time polymerase chain reaction system (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The primer sequences are detailed in Table 1. The final data were analyzed using the 2^(−ΔΔCT) method, and the mRNA expression levels were normalized to those of the β-actin gene.

Western blotting assays

Protein extraction and quantification were conducted using RIPA lysis buffer containing proteinase and phosphatase inhibitors and a BCA protein assay kit (P0010, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Equivalent amounts of total protein were subjected to electrophoresis (8–10% SDS‒PAGE) and subsequently transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk for 1 h, followed by overnight incubation at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: anti-HIF-1α (1:1000), anti-ANGPTL4 (1:500), anti-α-SMA (1:1000), anti-Col-I (1:500), and anti-β‐actin (1:5000) (66,009–1-lg, Wuhan, Proteintech). Subsequently, the membrane was incubated at room temperature for 1 h with secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:5000) (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Finally, the protein bands were visualized and quantified using enhanced chemiluminescence solution (WBKLS0100; Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) and ImageJ software.

Immunofluorescence staining

HK2 cells were inoculated into cell-climbing slices. Following the prescribed procedures, the cells were washed three times with PBS, sequentially fixed with a 4% polyformaldehyde solution, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton-X100, and blocked with 10% goat serum. Subsequently, the sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against HIF-1α (1:500) and ANGPTL4 (1:50). On the following day, the cells were incubated with a fluorescently labeled secondary antibody (1:800) (HA1121, Huaan, Hangzhou, China) at room temperature in the absence of light for 1 h. Nuclear staining with DAPI and mounting were subsequently performed. Finally, the samples were observed and imaged using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell transfection

ANGPTL4-siRNA, pcDNA3.1( +)-ANGPTL4, and their corresponding negative controls were obtained from HeYuan Biotech (Shanghai, China). HK2 cells were cultured in six-well plates and transfected when they reached 80% confluence. For the transfection experiments, Lipofectamine 3000 (L3000015; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA) reagent was used at a dose of 100 nM siRNA per well or 2.5 g of plasmid per well for a 24-h transfection period, after which the cells were induced with cobalt chloride (Cocl2) for 24 h. The target sequences for ANGPTL4 gene siRNAs were as follows: forward primer, 5'-GAACAGCAGGAUCCAGCAACUTT-3', and reverse primer, 5'-AGUUGCUGGAUCCUGCUGUUCTT-3'.

Statistical analysis

All the data were statistically analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA). Descriptive statistics for the quantitative variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Independent t tests were used for between-group parameter comparisons, while one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for multiple group comparisons. Pearson correlation analysis was performed to assess the correlation between two indicators. A P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Establishment of the CKD rat model

We administered 2.5% adenine (250 mg/kg) through gastric gavage to SD rats for 4 or 6 weeks to establish the CKD model. Initially, we assessed renal function. The CKD group had significantly greater levels of serum creatinine (Scr), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and 24-h urinary protein (24 h-Upro) than did the control group (Fig. 1A–C), and these levels continued to increase over time. Subsequently, renal pathological changes were evaluated using HE and Masson staining. HE staining revealed that the renal tissues of the control group exhibited normal structural organization, while those of the CKD group exhibited structural disarray. These changes included a decrease in glomerular size and atrophy, clear dilation of renal tubules with luminal destruction, inflammatory cell infiltration, and the deposition of brownish-yellow particles (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, Masson staining of the CKD group demonstrated a substantial accumulation of blue collagen fibers in the glomeruli and renal interstitium but not in the control group (Fig. 1D). Compared with that in the control group, the fibrotic area in the kidneys in the CKD group was significantly greater at various time points (Fig. 1E).

Establishment of the CKD rat model. The rats in the control group and the CKD group after 4 and 6 weeks of adenine gastric infusion were compared. A–C Quantities of Scr, BUN, and 24 h-Upro (n = 5/group). D HE staining of renal tissue. Masson staining revealed the deposition of blue collagen fibers (× 200 magnification, scale bar = 50 µm). E ImageJ was used for the quantitative assessment of the renal interstitial fibrosis area. All the data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. the control group at the same time

Increased expression of HIF-1α and ANGPTL4 in CKD rats

Immunohistochemical staining revealed decreased HIF-1α and ANGPTL4 protein expression in the control group, whereas at various time points, there was a significant increase in HIF-1α and ANGPTL4 expression in the CKD group (Fig. 2A–C). The majority of the genes are expressed in proximal renal tubules, with modest expression in renal glomeruli. Compared to those in the control group, the expression of the alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and collagen type I (Col-I) proteins in the renal interstitium in the CKD group increased at various time points (Fig. 2D, E). These proteins are considered indicative of interstitial or fibrotic phenotypes. Similarly, the qRT − PCR results demonstrated that the mRNA levels of Hif-1α, Angptl4, α-sma, and Col-I in the renal tissues of CKD rats at various time points were consistently greater than those in the control group (Fig. 2F–I). The findings of this study revealed a synchronous increase in the expression of HIF-1α and ANGPTL4 with the progression of RIF in CKD rats.

Increased expression of HIF-1α and ANGPTL4 in CKD rats. A Immunohistochemical staining to assess the expression of HIF-1α, ANGPTL4, α-SMA, and Col-I in the renal tissues of the two groups (× 200 magnification, scale bar = 50 µm). B–E Quantification of immunohistochemical staining (n = 5/group). F–I qRT‒PCR analysis of the expression of Hif-1α, Angptl4, α-sma, and Col-I mRNA in the renal tissues of the two groups of rats. All the data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. the corresponding control group at the same time point

To further ascertain the relationship between Angptl4 mRNA and renal interstitial fibrosis in CKD rats, we conducted Pearson correlation analysis and simple linear regression. The renal interstitial fibrosis area in CKD rats was significantly positively correlated with the expression of Angptl4 mRNA (r = 0.7737, P < 0.01) (Fig. 3A). Additionally, the expression of Angptl4 mRNA exhibited a robust correlation with renal injury markers, including Scr, BUN, and UP (r = 0.642, 0.8008, and 0.7609, respectively; P < 0.01) (Fig. 3B–D). Consequently, ANGPTL4 may play a critical role in the progression of RIF in CKD rats. Furthermore, the expression level of Angptl4 mRNA was positively correlated with the mRNA expression level of Hif-1α (r = 0.6665, P < 0.01) (Fig. 3E), suggesting a potential association between ANGPTL4 and HIF-1α.

Correlation analysis of Angptl4 levels with renal injury markers and Hif-1α levels. A Analysis of the correlation between Angptl4 levels and renal interstitial fibrosis area. B–D Correlation analysis of Angptl4 levels with Scr, BUN, and 24 h-Upro levels. E Analysis of the correlation between Angptl4 and Hif-1α

CKD patients with RIF exhibit elevated HIF-1α and ANGPTL4 expression

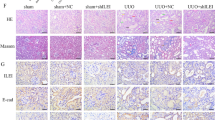

To validate the aforementioned findings in human samples, we analyzed the levels of HIF-1α and ANGPTL4 expression in renal biopsies from six CKD patients with RIF and five non-RIF CKD patients. The demographic and clinical information of the patients is detailed in Table 2. First, histological examinations using HE and Masson staining demonstrated varying degrees of blue collagen fiber deposition in the renal interstitium of the fibrosis group, accompanied by structural disarray in the kidney (Fig. 4A), in comparison to that in the nonfibrosis group. Then, immunohistochemical staining was conducted to observe the expression levels of HIF-1α and ANGPTL4. These results indicated a consistent increase in the expression of these genes, which was consistent with findings in rat models of adenine-induced RIF. Compared with those in the nonfibrosis group, the expression levels of HIF-1α and ANGPTL4 in the renal tissue of CKD patients with RIF were significantly elevated concomitant with the progression of RIF (Fig. 4B–E). Furthermore, Pearson correlation analysis revealed a significant positive correlation between the expression levels of ANGPTL4 and HIF-1α (r = 0.8569, P < 0.01) (Fig. 4F), confirming the association between ANGPTL4 and HIF-1α.

Increased expression of HIF-1α and ANGPTL4 in CKD patients with RIF. A Renal tissue was stained using HE and Masson's trichrome (× 400 magnification). B Immunohistochemical staining was used to assess the expression levels of HIF-1α, ANGPTL4, and α-SMA in the kidney (× 200 magnification, scale bar = 50 µm). C–E Quantification of immunohistochemical staining (the RIF group (n = 6) and the non-RIF group (n = 5)). F Analysis of the correlation between ANGPTL4 and HIF-1α. All the data are presented as the means ± standard deviations; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. the non-RIF group

The HIF-1α-ANGPTL4 pathway is activated in hypoxia-induced HK2 cell fibrosis

To validate the impact of the HIF-1α-ANGPTL4 pathway on RIF, we initially induced fibrosis in HK2 cells through 24 h of hypoxia. In comparison to those in the control group, the Western blotting results revealed substantial increases in the protein expression levels of HIF-1α, ANGPTL4, and the fibrotic markers α-SMA and Col-I after hypoxia treatment (Fig. 5A–E). Similar patterns were observed for mRNA expression (Fig. 5F–I). Immunofluorescence analysis indicated a significant increase in the nuclear expression of HIF-1α and the cytoplasmic expression of ANGPTL4 in hypoxia-induced HK2 cells (Fig. 5J). Subsequently, to explore whether HIF-1α regulates the expression of ANGPTL4 and TIF, we pretreated HK2 cells with the HIF-1α inhibitor 2-MeOE2 (5 μmol/L) for 12 h, followed by continued hypoxia for 24 h. The results demonstrated successful inhibition of HIF-1α expression after 2-MeOE2 treatment, which led to a marked decrease in both the protein and mRNA levels of ANGPTL4. This intervention also suppressed the hypoxia-induced upregulation of α-SMA and Col-I in HK2 cells (Fig. 6A–E). These findings suggest that the HIF-1α-ANGPTL4 pathway is activated in hypoxia-induced HK2 cell fibrosis.

The HIF-1α-ANGPTL4 pathway is activated in hypoxia-induced HK2 cell fibrosis. After 24 h of hypoxia induction in HK2 cells, an in vivo model of RIF induction was established. A Western blot analysis was conducted to assess the protein levels of HIF-1α, ANGPTL4, α-SMA, and Col-I, and the protein levels were quantified using ImageJ software (n = 3/group) (B–E). F–I qRT‒PCR was used to measure the mRNA expression of HIF-1α, ANGPTL4, α-SMA, and COL-I in each group. J–L Immunofluorescence staining for HIF-1α and ANGPTL4 (× 200 magnification, scale bar = 100 µm). All the data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. the control group

Impact of HIF-1α inhibitors on the levels of ANGPTL4 and fibrosis. HK2 cells were subjected to 2-MeOE2 (5 μmol/L) pretreatment for 12 h, followed by 24 h of hypoxia. A Western blot analysis was used to assess the protein levels of HIF-1α, ANGPTL4, α-SMA, and Col-I, and the protein levels were quantified using ImageJ software (n = 3/group) (B–E). F–I qRT‒PCR was utilized to evaluate the mRNA expression of HIF-1α, ANGPTL4, α-SMA, and COL-I in each group. All the data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. the control group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. the model group

Reduced or overexpressed ANGPTL4 affects HK2 cell fibrosis

To determine whether ANGPTL4 is a key factor in RIF, we transiently transfected HK2 cells with ANGPTL4 siRNA or plasmids for 24 h, induced ANGPTL4 inhibition or overexpression, and subjected them to subsequent 24-h hypoxic exposure. Western blotting revealed that ANGPTL4 protein expression was significantly lower in the ANGPTL4 siRNA group 48 h after transfection than in the scrambled siRNA group. Moreover, ANGPTL4 downregulation resulted in elevated levels of HIF-1α but strongly decreased the levels of the hypoxia-induced EMT-related marker α-SMA and the ECM deposition-related marker Col-I (Fig. 7A–E). Consistent results were demonstrated by qRT‒PCR analysis (Fig. 7F‒I). Similarly, overexpression of ANGPTL4 was evident in the pcDNA3.1( +)-ANGPTL4 group at 48 h posttransfection, in contrast to that in the pcDNA3.1( +) group. Upregulation of ANGPTL4 inhibited the expression of HIF-1α but exacerbated the increase in a-SMA and Col-I expression in hypoxia-induced HK2 cells (Fig. 7J–R). These results indicate that the expression level of ANGPTL4 can impact HK2 fibrosis, establishing ANGPTL4 as a crucial regulatory factor in RIF.

Reducing or overexpressing ANGPTL4 affects HK2 cell fibrosis. HK2 cells were transfected with ANGPTL4 siRNA for 24 h, followed by hypoxia-induced fibrosis for an additional 24 h. A Western blotting analysis was conducted to assess the protein levels of ANGPTL4, HIF-1α, α-SMA, and Col-I, and the protein levels were quantified using ImageJ software (n = 3/group) (B–E). F–I qRT‒PCR was used to evaluate the mRNA levels of ANGPTL4, HIF-1α, α-SMA, and COL-I in each group. HK2 cells were transfected with the ANGPTL4 plasmid for 48 h. J Western blotting analysis was used to evaluate the protein levels of ANGPTL4, HIF-1α, α-SMA, and Col-I, and quantitative analysis was carried out using ImageJ software (K–N). O–R qRT‒PCR was utilized to examine the mRNA expression of ANGPTL4, HIF-1α, α-SMA, and COL-I in each group. All the data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared to the control group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 compared to the scrambled siRNA ( +) or pcDNA3.1 ( +) group; ns: not significant

Discussion

In this study, we established an adenine-induced CKD rat model and a hypoxia-induced HK2 cell fibrosis model. A notable increase in the expression of ANGPTL4 was detected in both fibrotic kidneys and cells, and its preliminary validation was conducted on clinical samples. Building upon this foundation, we postulated that ANGPTL4 may influence the progression of RIF. Its impact on the progression of renal fibrosis was examined through the modulation of ANGPTL4 expression levels in vitro. Ultimately, ANGPTL4 was confirmed to be a critical molecular player in the occurrence and development of RIF in CKD, and it interacts with HIF-1α to form a regulatory loop (Fig. 8).

The model illustrates the role of ANGPTL4 in renal interstitial fibrosis. When renal interstitial fibrosis occurs due to various etiologies, the expression levels of HIF-1α and ANGPTL4 in the kidney significantly increase, and a negative regulatory mechanism is formed between the two. Modulating the expression of ANGPTL4 can markedly affect the accumulation of EMT and ECM components, ultimately impacting renal interstitial fibrosis. ANGPTL4 may serve as a pivotal molecular player in the occurrence and progression of renal interstitial fibrosis and is potentially emerging as a novel therapeutic target. Created with BioRender.com

ANGPTL4 is highly expressed in the adipose tissue and liver of both humans and mice, while its expression in the heart, muscles, kidneys, skin, and other tissues is comparatively reduced [24, 25]. Its expression is subject to regulation by nutritional factors such as fasting; diverse metabolic states, including hypoxia; and inflammatory conditions [26, 27]. Rademaker et al. [28], utilizing a sheep model, investigated acute kidney injury induced by acute decompensated heart failure. Transcriptome analysis revealed that ANGPTL4 might serve as a potential candidate marker for long-term renal dysfunction triggered by acute decompensated heart failure. It is also considered a diagnostic marker for both primary and metastatic clear-cell renal cell carcinoma [29]. Recent studies have reported that ANGPTL4 is upregulated in models of conditions such as IgA nephropathy [30], cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury [31], nephrotic syndrome [32,33,34], and diabetic nephropathy [35,36,37], promoting renal injury. To examine the expression pattern of ANGPTL4 in RIF, we established a CKD rat model through the intragastric administration of low-dose adenine. This effect was primarily achieved by adenine-induced persistent renal damage, glomerulosclerosis, tubular atrophy, and interstitial fibrosis, a recognized model closely resembling the gradual progression of human CKD [38]. This study employed this method to establish a model. It is clear that the CKD group showed a decrease in renal function in comparison to the control group, along with a significant increase in 24-h urinary protein excretion. Histological examinations utilizing HE and Masson staining revealed renal structural disarray and substantial collagen fiber deposition in the CKD group. The protein and mRNA levels of α-SMA and Col-I markedly increased and progressively increased with time, confirming the successful establishment of the model. In our study, the protein and mRNA expression levels of ANGPTL4 at various time points in the CKD group were significantly greater than those in the control group and showed a significant positive correlation with renal injury markers. Moreover, a marked increase in ANGPTL4 was also observed in the kidneys of CKD patients with RIF. These findings imply the potential involvement of ANGPTL4 in the occurrence and development of CKD-related RIF, which warrants further exploration.

HIF-1α can induce RIF through the modulation of gene transcription, cross-talk with various signaling pathways, EMT, and epigenetic regulation [14]. Furthermore, the regulation of ANGPTL4 expression by HIF-1α has been confirmed in various diseases, such as tumors, diabetes, and arterial sclerosis resulting from chronic intermittent hypoxia [13, 39, 40]. Nonetheless, research on this phenomenon in the context of the kidneys is limited. Liu et al.'s study [10] revealed a significant reduction in ANGPTL4 expression in a model of aristolochic acid nephropathy following the administration of a specific HIF-1α inhibitor. In our study, elevated HIF-1α protein and mRNA expression was distinctly observed in the fibrotic kidneys of CKD rats and patients compared to those of the control group, and the expression levels of HIF-1α were significantly positively correlated with ANGPTL4. Subsequent in vitro experiments induced fibrosis in HK2 cells through hypoxia, reaffirming the upregulation of HIF-1α and ANGPTL4 expression in the RIF model. After HK2 cells were treated with a HIF-1α inhibitor, the expression of ANGPTL4 significantly decreased. However, knocking down or overexpressing ANGPTL4 in turn affected the expression of HIF-1α. These findings indicate that HIF-1α can regulate the expression of ANGPTL4, which in turn is subject to negative feedback regulation by ANGPTL4, leading to a balanced state between the two. These findings reveal the presence of a negative feedback regulatory mechanism between HIF-1α and ANGPTL4 in RIF.

Recently, the role of ANGPTL4 in fibrosis has remained a subject of interest. Saito et al. [19] reported that in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and in a bleomycin-induced mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis, the expression of ANGPTL4 was significantly upregulated. Additionally, they used a recombinant ANGPTL4 intervention, which made the progression of pulmonary fibrosis much worse. In contrast, mice lacking ANGPTL4 showed improvements. Additionally, ANGPTL4 has been shown to be significantly upregulated in patients with cirrhosis and in cellular models of liver injury induced by the hepatitis C virus. Interfering with ANGPTL4 through the TLR4/NF-κB pathway can inhibit fibrosis in hepatic stellate cells and impede the progression of liver cirrhosis in mice [17, 41]. However, there is currently a lack of pertinent research on whether ANGPTL4 influences renal fibrosis. To further explore the impact of ANGPTL4 on RIF, we altered the expression of ANGPTL4 by transfecting HK2 cells with ANGPTL4 siRNA and plasmids. Our study revealed that the knockdown or overexpression of ANGPTL4 significantly suppressed or promoted the expression of the fibrosis markers α-SMA and Col-I, respectively. Therefore, our research revealed that ANGPTL4 may exacerbate the progression of RIF. Notably, following ANGPTL4 knockdown, the level of α-SMA remained greater than that in the control group, indicating that ANGPTL4 may not be the sole regulatory factor in renal fibrosis and that other HIF-1α-mediated regulatory pathways, such as the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, may also be involved [42]. Paradoxically, research has reported divergent effects of ANGPTL4 on cardiac fibrosis [43]. ANGPTL4 has been shown to play a potential protective role in a mouse model of angiotensin II-induced atrial fibrosis and in cardiac fibroblasts by modulating signaling pathways such as the PPARγ pathway [44, 45]. Furthermore, in a nonalcoholic fatty liver disease model, the absence of ANGPTL4 leads to the accumulation of free cholesterol in hepatic stellate cells, thereby exacerbating liver fibrosis [46]. These studies suggest that different intervention factors can induce varied expression levels of ANGPTL4 in different cell types, possibly attributed to the integrated functionality of its unique N-terminal and C-terminal domains. The specific outcomes depend on how the protein is hydrolyzed, cleaved, or changed after translation, leading to distinctly divergent pathological or therapeutic effects.

Nevertheless, there are several limitations to this investigation. First, the adenine-induced CKD rat model might not be representative of all forms of renal fibrosis. Second, we did not delve into the downstream mechanisms through which ANGPTL4 influences RIF. Finally, although we treated cells with HIF-1α inhibitors and knocked down or overexpressed ANGPTL4 in vitro, there is still a lack of in vivo studies on the use of HIF-1α and ANGPTL4 inhibitors in RIF, and future experiments in multiple renal models are needed for validation. Therefore, these aspects will be focal points in our forthcoming research endeavors.

Conclusions

This research substantiates, for the first time, that ANGPTL4 serves as a pivotal regulatory factor in RIF. Our study revealed the activation of the ANGPTL4 signaling pathway in both CKD rat models and patients. Furthermore, the interaction between ANGPTL4 and HIF-1α forms a regulatory loop, thereby modulating fibrosis-associated markers and actively participating in the progression of RIF. These findings suggest that ANGPTL4 may be a novel therapeutic target for the prevention and treatment of RIF.

Availability of data and materials

All the data generated or analyzed during this research period were incorporated into the published manuscript.

Abbreviations

- 24 h-Upro:

-

24-Hour urine protein

- ANGPTL4:

-

Angiopoietin-like 4

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- Col-I:

-

Collagen I

- ECM:

-

Extracellular matrix

- EMT:

-

Epithelial mesenchymal transition

- HIF-1α:

-

Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α

- qRT‒PCR:

-

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- RIF:

-

Renal interstitial fibrosis

- Scr:

-

Serum creatinine

- siRNA:

-

Small interfering RNA

- α-SMA:

-

α-Smooth muscle actin

References

Chen TK, Knicely DH, Grams ME. Chronic kidney disease diagnosis and management: a review. JAMA. 2019;322(13):1294–304. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.14745.

Webster AC, Nagler EV, Morton RL, Masson P. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet. 2017;389(10075):1238–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(16)32064-5.

Shen YL, Wang SJ, Rahman K, Zhang LJ, Zhang H. Chinese herbal formulas and renal fibrosis: an overview. Curr Pharm Des. 2018;24(24):2774–81. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612824666180829103355.

Huang R, Fu P, Ma L. Kidney fibrosis: from mechanisms to therapeutic medicines. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):129. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01379-7.

Yan HH, Jung KH, Lee JE, Son MK, Fang Z, et al. ANGPTL4 accelerates KRAS(G12D)-Induced acinar to ductal metaplasia and pancreatic carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2021;519:185–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2021.07.036.

Gordon ER, Wright CA, James M, Cooper SJ. Transcriptomic and functional analysis of ANGPTL4 overexpression in pancreatic cancer nominates targets that reverse chemoresistance. Res Sq. 2023. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2444404/v1.

Mukhopadhyay S, Huang HY, Lin Z, Ranieri M, Li S, et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screens identify multiple synthetic lethal targets that enhance KRASG12C inhibitor efficacy. Cancer Res. 2023;83(24):4095–111. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.Can-23-2729.

Santulli G. Angiopoietin-like proteins: a comprehensive look. Front Endocrinol. 2014;5:4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2014.00004.

Carbone C, Piro G, Merz V, Simionato F, Santoro R, et al. Angiopoietin-like proteins in angiogenesis, inflammation and cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19020431.

Liu G, He L. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate attenuates adriamycin-induced focal segmental glomerulosclerosis via suppression of oxidant stress and apoptosis by targeting hypoxia-inducible factor-1α/angiopoietin-like 4 pathway. Pharmacology. 2019;103(5–6):303–14. https://doi.org/10.1159/000496799.

Wei X, Zhu X, Jiang L, Huang X, Zhang Y, et al. Recent advances in understanding the role of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α in renal fibrosis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2020;52(7):1287–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-020-02474-2.

Li ZL, Liu BC. Hypoxia and renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1165:467–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-8871-2_23.

Tang JJ, Li GX, Liu ZG, Yi R, Yu D, et al. Danlou tablet improves chronic intermittent hypoxia-induced dyslipidemia and arteriosclerosis by HIF-1α-Angptl4 mRNA signaling pathway. Chin J Integr Med. 2022;28(6):509–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11655-020-3255-8.

Liu J, Wei Q, Guo C, Dong G, Liu Y, et al. Hypoxia, HIF, and associated signaling networks in chronic kidney disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(5):905. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18050950.

Liu D, Sun H, Li K, Zhao Z, Liu Z, et al. HIF-1α mediates renal fibrosis by regulating metabolic remodeling of renal tubule epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2022;618:15–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2022.06.008.

Zhao H, Han Y, Jiang N, Li C, Yang M, et al. Effects of HIF-1α on renal fibrosis in cisplatin-induced chronic kidney disease. Clin Sci (Lond). 2021;135(10):1273–88. https://doi.org/10.1042/cs20210061.

Valiakou V, Eliadis P, Karamichali E, Tsitsilonis O, Koskinas J, et al. Differential expression of the host lipid regulators ANGPTL-3 and ANGPTL-4 in HCV infection and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(15):7961. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22157961.

Saito M, Mitani A, Ishimori T, Miyashita N, Isago H, et al. Active mTOR in lung epithelium promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and enhances lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2020;62(6):699–708. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2019-0255OC.

Saito S, Kitabatake M, Ouji-Sageshima N, Ogawa T, Oda A, et al. Angiopoietin-like 4 Is a critical regulator of fibroblasts during pulmonary fibrosis development. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2023;69(3):328–39. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2022-0304OC.

Li Y, Mao H, Kang T, Zhang L, Liu Q, et al. Angiopoietin-like protein 4 signaling pathway’s expression and functionality in the adenine-induced chronic renal disease rat model. Chin J Neahrol. 2023;39(2):126–34. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn441217-20220708-00712.

Mao H, Chen L, Wu W, Zhang L, Li X, et al. Noninvasive assessment of renal fibrosis of chronic kidney disease in rats by [(68)Ga]Ga-FAPI-04 small animal PET/CT and biomarkers. Mol Pharm. 2023;20(5):2714–25. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.3c00163.

Manotham K, Tanaka T, Matsumoto M, Ohse T, Inagi R, et al. Transdifferentiation of cultured tubular cells induced by hypoxia. Kidney Int. 2004;65(3):871–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00461.x.

Zhang Y, Mi Y, He C. 2-methoxyestradiol restrains non-small cell lung cancer tumorigenesis through regulating circ_0010235/miR-34a-5p/NFAT5 axis. Thorac Cancer. 2023;14(22):2105–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-7714.14993.

Guo L, Li SY, Ji FY, Zhao YF, Zhong Y, et al. Role of Angptl4 in vascular permeability and inflammation. Inflamm Res. 2014;63(1):13–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-013-0678-0.

Kersten S, Mandard S, Tan NS, Escher P, Metzger D, et al. Characterization of the fasting-induced adipose factor FIAF, a novel peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor target gene. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(37):28488–93. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M004029200.

Zuo Y, He Z, Chen Y, Dai L. Dual role of ANGPTL4 in inflammation. Inflamm Res. 2023;72(6):1303–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-023-01753-9.

Hato T, Tabata M, Oike Y. The role of angiopoietin-like proteins in angiogenesis and metabolism. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2008;18(1):6–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcm.2007.10.003.

Rademaker MT, Pilbrow AP, Ellmers LJ, Palmer SC, Davidson T, et al. Acute decompensated heart failure and the kidney: physiological, histological and transcriptomic responses to development and recovery. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(18): e021312. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.121.021312.

Verine J, Lehmann-Che J, Soliman H, Feugeas JP, Vidal JS, et al. Determination of angptl4 mRNA as a diagnostic marker of primary and metastatic clear cell renal-cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(4): e10421. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0010421.

Jia S, Peng X, Liang L, Zhang Y, Li M, et al. The study of angptl4-modulated podocyte injury in IgA nephropathy. Front Physiol. 2020;11: 575722. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.575722.

Li S, Nagothu K, Ranganathan G, Ali SM, Shank B, et al. Reduced kidney lipoprotein lipase and renal tubule triglyceride accumulation in cisplatin-mediated acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;303(3):F437-448. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00111.2012.

Lu R, Zhou J, Liu B, Liang N, He Y, et al. Paeoniflorin ameliorates Adriamycin-induced nephrotic syndrome through the PPARγ/ANGPTL4 pathway in vivo and vitro. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;96:137–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2017.09.105.

Li Y, Xu Z, Deng H, Liu M, Lin X, et al. ANGPTL4 promotes nephrotic syndrome by downregulating podocyte expression of ACTN4 and podocin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2023;639:176–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2022.11.081.

Wang X, Qi D, Fu F, Li X, Liu Y, et al. Therapeutic and antiproteinuric effects of salvianolic acid A in combined with low-dose prednisone in minimal change disease rats: involvement of PPARγ/Angptl4 and Nrf2/HO-1 pathways. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;858: 172342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.04.023.

Qin L, Zhang R, Yang S, Chen F, Shi J. Knockdown of ANGPTL-4 inhibits inflammatory response and extracellular matrix accumulation in glomerular mesangial cells cultured under high glucose condition. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2019;47(1):3368–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/21691401.2019.1649274.

Wang Z, Wu Q, Wang H, Gao Y, Nie K, et al. Diosgenin protects against podocyte injury in early phase of diabetic nephropathy through regulating SIRT6. Phytomedicine. 2022;104: 154276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154276.

Gao Y, Ma Y, Xie D, Jiang H. ManNAc protects against podocyte pyroptosis via inhibiting mitochondrial damage and ROS/NLRP3 signaling pathway in diabetic kidney injury model. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;107: 108711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2022.108711.

Diwan V, Brown L, Gobe GC. Adenine-induced chronic kidney disease in rats. Nephrology. 2018;23(1):5–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/nep.13180.

Kang YT, Li CT, Tang SC, Hsin IL, Lai YC, et al. Nickel chloride regulates ANGPTL4 via the HIF-1α-mediated TET1 expression in lung cells. Toxicol Lett. 2021;352:17–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2021.09.007.

Yang X, Cao J, Du Y, Gong Q, Cheng Y, et al. Angiopoietin-like protein 4 (ANGPTL4) induces retinal pigment epithelial barrier breakdown by activating signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3): evidence from ARPE-19 cells under hypoxic condition and diabetic rats. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:6742–54. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.915748.

Zhang X, Yuan S, Zhang X, Zhang T, Meng C, et al. ANGPTL4 regulates CD163 expression and Kuppfer cell polarization induced cirrhosis via TLR4/NF-κB pathway. Exp Cell Res. 2021;405(2): 112706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexcr.2021.112706.

Liu D, Wang L, Ha W, Li K, Shen R, et al. HIF-1α: a potential therapeutic opportunity in renal fibrosis. Chem Biol Interact. 2024;387: 110808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2023.110808.

Cho DI, Kang HJ, Jeon JH, Eom GH, Cho HH, et al. Antiinflammatory activity of ANGPTL4 facilitates macrophage polarization to induce cardiac repair. JCI Insight. 2019;4(16): e125437. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.125437.

Zhu X, Zhang X, Cong X, Zhu L, Ning Z. ANGPTL4 attenuates Ang II-induced atrial fibrillation and fibrosis in mice via PPAR pathway. Cardiol Res Pract. 2021;2021:9935310. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9935310.

Zhu X, Zhang X, Gu W, Zhao H, Hao S, et al. ANGPTL4 suppresses the profibrogenic functions of atrial fibroblasts induced by angiotensin II by up-regulating PPARγ. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2023;26(5):587–93. https://doi.org/10.22038/ijbms.2023.69196.15077.

Teratani T, Tomita K, Wada A, Sugihara N, Higashiyama M, et al. Angiopoietin-like protein 4 deficiency augments liver fibrosis in liver diseases such as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice through enhanced free cholesterol accumulation in hepatic stellate cells. Hepatol Res. 2021;51(5):580–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/hepr.13603.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to BioRender (www.BioRender.com) for their graphical assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Luzhou Municipal People’s Government-Southwest Medical University Science and Technology Strategic Cooperation Project Fund (2021LZXNYD-J11).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OST and LY conceptualized and designed this study; CS and YQ conducted the animal experiments; LY and ZWM performed the in vitro experiments; LX collected patient information and conducted renal histological staining; and KT and WWH carried out the data analysis and processing. LY drafted the manuscript, which was subsequently revised by OST. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The animal experiments in this study received approval from the Animal Ethics Committee of Southwest Medical University (SWMU20210397). The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Clinical Trial Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University.

Consent for publications

All the authors have perused the manuscript and concurred on its publication.

Competing interests

All the authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Chen, S., Yang, Q. et al. The ANGPTL4-HIF-1α loop: a critical regulator of renal interstitial fibrosis. J Transl Med 22, 649 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-024-05466-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-024-05466-3