Abstract

Zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1, also termed TCF8 and δEF1) is a crucial member of the zinc finger-homeodomain transcription factor family, originally identified as a binding protein of the lens-specific δ1-crystalline enhancer and is a pivotal transcription factor in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process. ZEB1 also plays a vital role in embryonic development and cancer progression, including breast cancer progression. Increasing evidence suggests that ZEB1 stimulates tumor cells with mesenchymal traits and promotes multidrug resistance, proliferation, and metastasis, indicating the importance of ZEB1-induced EMT in cancer development. ZEB1 expression is regulated by multiple signaling pathways and components, including TGF-β, β-catenin, miRNA and other factors. Here, we summarize the recent discoveries of the functions and mechanisms of ZEB1 to understand the role of ZEB1 in EMT regulation in breast cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is the transdifferentiation process that causes epithelial cells to lose their epithelial characteristics, such as cell junctions and apical-basal polarity, and acquire mesenchymal characteristics, such as increased cell motility and invasive ability [1]. EMT is critical for normal developmental processes, such as embryonic stem cell differentiation and induced pluripotency, and is involved in disease development processes, such as wound healing, fibrosis, cancer stem cell (CSC) behaviors and cancer development/migration. EMT occurs in breast cancer, providing highly mobile and invasive cancer cells for further metastasis.

Over the past decades, extensive research has focused on the function of EMT and its underlying molecular mechanisms. Lamouille et al. reviewed the molecular mechanisms of EMT and summarized EMT transcription factors with their direct targets and signaling pathways [2]. Most of the EMT transcription factors regulated epithelial/mesenchymal markers (such as E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and vimentin) directly or indirectly during both normal development and physiopathological processes. Among these transcription factors, ZEB1 is a candidate repressor of E-cadherin [3] as are other zinc finger E-box binding (ZEB) family members [4], the Snail family of transcription factors [5] and basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) factors [6].

The ZEB1 protein participates in the differentiation of multiple tissues, including bone tissue [7], smooth muscle tissue [8], neural tissue [9], etc. ZEB1 can decrease the expression of the epithelial marker E-cadherin [10] and related miR-200 s [11], resulting in the EMT process. Abnormal expression of ZEB1 has been reported in various human cancers, including pancreatic cancer [12], lung cancer [13], liver cancer [14], colon cancer [15], and breast cancer [16]. Additionally, the increased expression of ZEB1 enhanced the chemo/radioresistance of cancer cells [17], indicating that ZEB1 is not only involved in the oncogenesis and development of cancers but also affects the prognosis of cancer patients. This review will focus on the EMT transcription factor ZEB1 and its functions in the oncogenesis and development of breast cancer.

Transcription factor ZEB1 and its structural characteristics

ZEB homeobox is a transcription factor family that includes ZEB1 (also known as TCF8 and δEF1) and ZEB2 (also known as SIP1) [18]. Both of them contain C2H2-type zinc fingers, the common DNA-binding motifs binding to paired CAGGTA/G E-box-like elements in the promoters of their target genes, and regulate cell differentiation and tissue-specific functions [19, 20]. ZEB1 is located on Chr10p11.22 and encodes the 1117 amino acid ZEB1 protein, which mainly consists of the homologous structural domain homeodomain (HD) in the middle of the structure and the structures of the zinc finger N-terminal cluster (NZF) and C-terminal cluster (CZF) on both sides (Fig. 1).

The schematic structure of ZEB1/2. The structures of ZEB1/2 are similar, with N-terminal and C-terminal zinc finger (NZF and CZF) and a central Homeodomain (HD). The ZEB1/2 protein interacted with other proteins through a corresponding binding domain, including the CAF/p300 binding domain (CBD) at the N-terminal, Smad interaction domain (SID) and CtBP interaction domain (CID) at the C-terminal

The expression pattern of ZEB1 in breast cancers and its molecular mechanism of transcriptional suppression

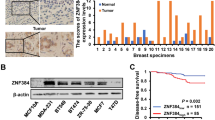

The expression of ZEB1 in breast cancer

The expression level of ZEB1 is increased in triple-negative breast cancers (TNBCs) and basal-like breast cancers compared to the luminal subtype [21]. To understand the role of ZEB1 in TNBCs, Lehmann et al. compared the different gene expression levels between aggressive TNBC cancer cells (MDA-MB-231) with high ZEB1 levels and their corresponding ZEB1 knockdown cells, revealing that the expression of 60% of genes was upregulated after ZEB1 knockdown and that the remaining genes were downregulated [22]. They predicted potential direct or indirect target genes of the transcriptional repressor ZEB1 and suggested that abnormal expression of the gene set may be a predictor of poor survival, therapy resistance and increased metastatic risk in breast cancer [22].

ZEB1 functions as a transcriptional suppressor

As mentioned before, the main transcriptional function of ZEB1 is suppressing the expression of its target genes, such as epithelial markers (E-cadherin), and correspondingly increasing the mesenchymal levels of vimentin and N-cadherin [23]. Eger et al. first reported ZEB1 as a direct transcriptional repressor of E-cadherin by physically binding to the proximal promoter of E-cadherin in breast cancers [10]. As a transcriptional repressor, it was identified that ZEB1 can also directly bind to the promoter of miR-190, resulting in transcriptional suppression of miR-190 expression, which can reverse the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β-induced EMT process [24]. Most importantly, the expression of the miR-200 family members was suppressed by ZEB1 binding to their promoters and was conversely involved in the regulation of ZEB1 levels as a reciprocal ZEB1/miR-200 feedback loop [25, 26].

A various set of cofactors were also recruited during the transcriptional suppression process of ZEB1 for its downstream target genes [27, 28], although only a few of them were reported [29]. ZEB1 activation requires interaction with PC2-CtBP-LSD1-LCoR or the yeast mating-type switching/sucrose non-fermenting (SWI/SNF) chromatin-remodeling protein BRG1 to form the ZEB1-Smad3-p300-P/CAF complex, affecting general transcription [28]. The effector of the Hippo/Yes-associated protein (YAP) pathway, YAP, can specifically and directly interact with ZEB1, converting ZEB1 from a transcriptional repressor to a transcriptional activator that binds to conserved TEAD-binding sites. As a result, functional cooperation between ZEB1 and YAP can stimulate the transcriptional activities of a ‘common ZEB1/YAP target gene set’, such as connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and AXL receptor tyrosine kinase (AXL) [22].

Usually, the functional statuses of chromatin are identified by the covalent modification pattern of the N-terminal domains of the histones, indicating the transcriptional activity of their target genes. For example, histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) was reported to be associated with transcriptional initiation [30], while lysine 79 dimethylation (H3K79me2) was associated with promoting transcriptional elongation [31]. Overall the combined effect of H3K4me3 and H3K79me2 contributes to the activation of gene transcription. In addition, lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) was suggested to contribute to transcriptional repression [32,33,34,35]. An innovative and interesting study found that luminal breast cancer cell lines exhibited only presence of H3K27me3 and the relative absence of 3K4me3 and H3K79me2 at the ZEB1 promoter [29]. Oppositely, in basal-like or basal CD44hi breast cancer cells, high expression levels of ZEB1 were controlled by H3K4me3 and H3K79me2 in its promoter, which did not have H3K27me3, indicating active transcription. More importantly, the ZEB1 promoter in basal CD44lo cells or plastic non-CSCs showed a bivalent chromatin configuration, enabling these cells to respond readily to microenvironmental signals, such as TGF-β [29].

The regulation of ZEB1 expression and activity

As an important transcriptional factor, the expression of ZEB1 is also regulated at multiple levels [36]. Signal transducer and activator of transcription3 (STAT3) has been reported to induce the expression of ZEB1 [37]. Avtanski et al. identified that honokiol (HNK) is an active bisphenol molecule that inhibits the function of STAT3 by repressing STAT3 phosphorylation and the transactivation potential; STAT3 recruitment to the ZEB1 promoter is then reduced, which causes decreased ZEB1 expression and nuclear translocation. In addition, HNK-mediated STAT3 inactivation triggered the STAT3-mediated release of ZEB1 from the E-cadherin promoter, increasing E-cadherin expression and inhibiting EMT of breast cancer cells accordingly [37].

After the formation of the ZEB1 protein, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) induced ZEB1 phosphorylation at residues T851, S852, and S853 by protein kinase C (PKC), showing involvement in the EMT process and resulting in transcriptional activity [38]. Another posttranslational modification of ZEB1 is polycomb protein (Pc2)-induced sumoylation at residues K347 and K777 [39].

The stability of EMT-related transcription factors is essential for initiating cellular EMT. Thus, the deubiquitinases (DUBs) were involved in counteracting polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of ZEB1 [40]; these DUBs include USP51, which upregulated ZEB1 and the mesenchymal markers by binding, deubiquitinating, and stabilizing ZEB1 [41]. In addition to DUBs, other factors, such as CSN5, an oncogene involved in various types of cancer, may also interrupt the degradation of ZEB1 by stabilizing ZEB1 by directly interacting with it [42]. The phosphorylation of ZEB1 by ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase stabilizes ZEB1 in response to DNA damage [43].

The new findings related to posttranslational modifications that regulate ZEB1 provide an alternative pathway for precision medicine to treat breast cancer by targeting ZEB1.

The reciprocal ZEB1/target feedback loops involved in breast cancers

As a transcriptional suppressor, ZEB1 is involved in many signaling pathways to inhibit the expression of its targets. Interestingly, some of the targets of ZEB1, such as the ZEB1/miR-200s loop, function as a regulator of ZEB1 to control the level and function of ZEB1.

ZEB1/miR-200s loop

Independent investigations revealed that miR-200 family members, including miR-200a/b/c, miR-141 and miR-429, can revert the EMT process and are powerful inducers of epithelial differentiation. The mechanism of miR-200s suppressing ZEB1 involved posttranscriptional repression by binding to the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of ZEB1 mRNA, which contains 8 miR-200s binding sites [11, 44, 45]. As mentioned before, in addition to the inhibitory function of miR-200s on ZEB1, the expression of miR-200s can be reversely suppressed by ZEB1 through direct binding to the highly conserved sites in the promoter common to the miR-200 family members [25]. Notably, ZEB1 and miR-200s have the opposite functions to regulate EMT and the characteristics of cancer cells but also reciprocally control the expression of each other, which is a double-negative feedback loop named the ZEB1/miR200 feedback loop [25, 26]. Depending on the different extracellular signals, the unstable status of the ZEB1/miR-200 feedback loop will strongly promote the expression and effect of one group and will correspondingly suppress those of the other group, resulting in the switch from one phenotype to another phenotype and stabilizing their epithelial/mesenchymal phenotype accordingly [46].

The ZEB1/miR-200 feedback loop was indicated to regulate EMT and, more importantly, was supposed to be a central switch for other crucial cellular functions, such as survival vs. apoptosis, stemness vs. differentiation, growth arrest vs. proliferation, and longevity vs. senescence [46]. In breast cancer, the studies of this loop mainly focused on mesenchymal-like characteristics involving different pathways or factors, such as the H-Ras signaling pathway [47], as well as the transcription factor zinc finger protein 217 (ZNF217) [25]. It was reported that autocrine TGF-β, which is upregulated by ZNF217, transcriptionally activated the expression of ZEB1 and finally exhibited feedback inhibition on miR-200c [48, 49]. Using the intertwined feedback loop, Bai et al. found the underlying mechanism of trastuzumab resistance and metastasis in breast cancer where miR-200c targeted ZNF217 and ZEB1 to suppress TGF-beta signaling [50].

ZEB1/MYB loop

ZEB1/MYB is another reciprocal negative feedback circuit involved in the process of breast cancer development. Both ZEB1 and MYB are transcription factors that function as biological switches for molecular elements of their targets, affecting the tumor microenvironment and cell morphology. On one hand, ZEB1 transcriptionally suppressed the expression of MYB by controlling the positive feedback cycle of MYB. On the other hand, MYB was found to inhibit ZEB1 expression and correspondingly alleviate the ZEB1-mediated transcriptional repression of CDH1, restoring the epithelial phenotype [51]. The dual-negative regulation of ZEB1/MYC is thought to be the molecular mechanism of cell plasticity, regulating the state of tumor stem cells and promoting tumor invasion and metastasis.

ZEB1/grainyhead-like-2 (GRHL2) loop

GRHL2 was found to be downregulated specifically in claudin-low subclass breast cancers and to suppress TGF-β-induced, Twist-induced or spontaneous EMT partially by suppressing ZEB1 expression by directly binding to the ZEB1 promoter [52]. Soon after, Cieply et al. revealed that (1) GRHL2 altered the Six1-DNA complex to inhibit the transactivation of the ZEB1 promoter; and that (2) the combination of TGF-β and Wnt activation interacted with ZEB1 directly, affecting the activities of the GRHL2 promoter to suppress its expression; these results indicate a reciprocal GRHL2 and ZEB1 feedback loop that controls epithelial/mesenchymal phenotypes and EMT progress [53].

ZEB1/CD44s loop

In addition to negative feedback loops, ZEB1 was also involved in the positive dual promotion process with its targets. ZEB1 was correlated with maintaining stem cell specialties and cell survival in tumorigenesis [54], and a positive feedback loop between CD44s and ZEB1 was involved [46]. CD44s is the active type to promote the expression of ZEB1 and is controlled by epithelial splicing regulatory protein 1 (ESPR1) through alternative splicing of CD44, causing a shift from the variant CD44v to the standard CD44s isoform [55]. To maintain the stemness and mesenchymal features of cancer cells, ZEB1, in turn, inhibited transcription of the splicing factor ESRP1, causing the switch from CD44 splicing to preferentially express CD44s and resulting in self-sustained ZEB1/CD44s expression, which promoted both EMT and breast cancer development [56].

ZEB1/hyaluronic acid synthase 2 (HAS2) loop

Hyaluronic acid (HA), synthesized mainly by HAS2, is one major extracellular matrix (ECM) proteoglycan that is enriched in mammary tumors [57]. Preca et al. reported a new positive feedback loop consisting of HAS2 and ZEB1 [58]. Extracellular HA contributed to ZEB1-driven EMT by triggering ZEB1 expression and was enhanced by HA-induced CD44s, indicating that HAS2 is necessary for TGF-β-induced EMT and that ZEB1 directly binds to the HAS2 promoter and activates its expression, further enhancing ZEB1 expression and shaping the microenvironment [58]. Interestingly, this positive ZEB1/HAS2/HA feedback loop will be facilitated by the ZEB1/ESRP1/CD44s loop, providing insight into a complex multifactorial positive feedback system.

The oncogenic functions of ZEB1 in breast cancer and their underlying mechanisms

Cell plasticity

CSCs, which are considered the subset of neoplastic cells in a highly tumorigenic state, contribute to phenotypic and functional heterogeneity in cancers [59]. Interestingly, an innovative study conducted by Chaffer et al. demonstrated that non-CSCs of human basal breast cancers are a plastic cell population, with the potential to switch from a non-CSC-state to a CSC-state; this switch is regulated by the condition of the ZEB1 promoter responding to microenvironmental signals (such as TGF-β) [29]. Accordingly, the active chromatin configuration of the ZEB1 promoter significantly increased the CD44lo/hi ratio, predicting the critical role of ZEB1 for the transition of cell types from CD44lo to CD44hi and for the generation of CSCs from non-CSC cells, maintaining the activities of CD44hi/CSC-like cells [29].

Similarly, ZEB1 was involved in Wnt/β-catenin signaling to promote cancer cell metastasis [60]. Aberrant levels of ZEB1 suppressed the expression of epithelial splicing regulatory proteins (ESRPs) [61, 62], promoting a shift from the epithelial isoform (CD44v8-9) to the mesenchymal isoform (CD44s) [63, 64]. Cyclin-dependent protein kinase-like 2 (CDKL2) was demonstrated to activate a positive feedback circuit, the ZEB1/E-cadherin/β-catenin signaling pathway, to enhance the mesenchymal characteristics and stem cell-like properties [65]. CDKL2 upregulated the expression of ZEB1 through increasing the promoter activities of ZEB1, while it has also been reported as a well-established transcriptional suppressor of E-cadherin [10]. Subsequently, a decreased level of E-cadherin destroyed the epithelial barrier [66], causing nuclear translocation of β-catenin and increased β-catenin/TCF4 transcriptional activity, which accordingly promoted ZEB1 promoter activity and transcriptional function [60], leading to further suppression of E-cadherin expression and sustaining activation of the positive feedback circuit. Finally, the EMT process was promoted by ZEB1 through the E-cadherin/β-catenin signaling pathway and strengthened the CD44 high mesenchymal properties under CDKL2 regulation [65].

Interestingly, in addition to the transition between the epithelial (E) and mesenchymal (M) states, Lu et al. proposed the “ternary chimera switch (TCS)” model and proposed a third state with intermediate levels of both miR-200 and ZEB, corresponding to the epithelial-mesenchymal (E/M) hybrid phenotype [67]. Further, Zhang et al. confirmed that the SNAIL1/miR-34 module forms a biswitch between the E and E/M transitions, and the ZEB1/miR-200 module is another biswitch for the transition from the E/M to M state [68].

On the other hand, Drosophila Lgl and its mammalian homologs, LLGL1/2, are scaffolding proteins that regulate the establishment of apical-basal polarity in normal epithelial cells, and LLGL2 also combined with SLC7A5 (a leucine transporter) and YKT6 (a regulator of membrane fusion) to form a trimeric complex, promoting leucine uptake, cell proliferation and resistance to endocrine treatment in ER-positive breast cancers [69]. ZEB1 has a specific property to modulate asymmetric-symmetric cell division through the transcriptional repression of the polarity protein LLGL1/2 by binding to their specific promoter regions, resulting in induced EMT and regulating the polarity of stem cell division to maintain the mammary epithelial homeostasis [70]. In addition to normal mammary epithelia, the epithelial polarity of breast cancer cells can be partially restored by knockdown of ZEB1 to accumulate LLGL2 in the cytoplasm [71].

Tumor growth, metastasis, and EMT

As shown in Fig. 2, the aberrant expression of ZEB1 is thought to be connected with tumorigenesis and poor prognosis in various tumors, especially in breast cancer [72,73,74,75,76]. In primary breast cancer, the increased ZEB1 suppressed the expression of epithelial marker E-cadherin and induced the EMT process, indicating that the transformed tumor cells with high ZEB1 level lost their epithelial characteristics and developed a mesenchymal/motile phenotype. Conversely, mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) process was occurred with decreased ZEB1 level, when metastatic breast cancer was formed in a distant location, to recover the epithelial features and lose the mesenchymal/motile phenotype with a low ZEB1 level (Fig. 2). Enhanced metastatic potential was associated with overexpression of ZEB1 in a mouse xenograft model of breast cancer, suggesting the role of ZEB1 in invasion and metastasis of human tumors [77]. On the other hand, ZEB1 contributes to the formation of the tumor microenvironment by regulating the levels of various inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin 6/8 (IL-6/8), which resulted in increased tumor growth in basal-like breast cancer cells [78]. Recently, Fu et al. revealed the important role of the ZEB1/p53 axis in stromal fibroblasts to promote mammary epithelial tumors, which demonstrated the high expression and activation of ZEB1 in the stroma was associated with increased ECM remodeling, immune cell infiltration and angiogenesis through increasing FGF2/7, VEGF and IL-6 expression and secretion into the surrounding stroma [79].

ZEB1-involved EMT and mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) processes. In primary breast cancer, the increased ZEB1 level suppressed the expression of the epithelial marker E-cadherin and induced the EMT process. The transformed tumor cells with high ZEB1 levels lost their epithelial characteristics, developed a mesenchymal/motile phenotype, and subsequently invaded into lymph or blood vessels. When metastatic breast cancer was formed in a distant location, the ZEB1 expression level was decreased to promote the expression of the epithelial marker E-cadherin and inhibit the expression of the mesenchymal marker Vimentin, occurring the mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) process to recover the epithelial features and lose the mesenchymal/motile phenotype with a low ZEB1 level

Tumor vascularization predicted the deprivation of nutrients and oxygen and facilitated the metastasis process of tumor cells through vessel formation with or without endothelial transdifferentiation. During this process, the secreted proteins fibronectin 1 (FN1) and serine protease inhibitor family E member 2 (SERPINE2) are essential for vascular mimicry (VM) in this system. These secreted factors were upregulated in mesenchymal cells by ZEB1-repressed miRNA clusters, promoting autocrine signaling, which was followed by increased VM in breast cancer cells [80]. In clinical studies, ZEB1 was found to be significantly associated with the depth of invasion, lymph node metastasis and TNM stage in digestive cancer patients, as well as in patients with breast cancer [81].

Chemoresistance

Currently, chemoresistance has become a major challenge and research hotspot in cancer treatment, referring to the increased tolerance of tumor cells to chemotherapeutic drugs and a decreased chemotherapeutic effect [82, 83]. CSCs have a self-renewal ability, can activate survival signaling pathways and can protect tumor cells from DNA damage and reactive oxygen species (ROS), contributing to drug resistance [84].

Increasing evidence indicates that ZEB1 has important significance in therapeutic resistance [85, 86]. Wang et al. found that breast cancer patients with high ZEB1 levels showed poor responses to epirubicin (EPI), indicating ZEB1 as the determinant of chemoresistance in breast cancer, involving DNA damage repair (DDR) [17]. In a large cohort of human breast cancer subjects, high levels of ZEB1 were shown to have positive relationships with Bcl-xl and cyclin D1, predicting a poor response to chemotherapy [77]. The researchers investigated the molecular mechanisms and found that the ZEB1/p300/PCAF (P300/CBP-associated factor, PCAF) complex bound to the ATM promoter and accordingly transcriptionally activated ATM, subsequently promoting homologous recombination (HR)-mediated DDR to clean up the chemotherapy-induced DNA fragments [77].

Endocrine therapy is an important therapeutic strategy for breast cancer patients with ER-positive expression; however, antiestrogen resistance has become a major obstacle in endocrine therapy and involves reduced estrogen receptor-alpha (ER-α) expression. Zhang et al. discovered that ZEB1 mechanistically inhibited ER-α transcription through the ZEB1/DNA methyltransferase 3B (DNMT3B)/histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) complex binding to hypermethylate and silence the ER-α promoter, subsequently attenuating the responsiveness of breast cancer cells to antiestrogen treatment [87]; these results indicate that ZEB1 is a key determinant of antiestrogen resistance in breast cancer.

Trastuzumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), provides a successful therapeutic strategy for HER2-overexpressed breast cancer. Unfortunately, decreased trastuzumab sensitivities developed in most patients within a year [88]. Bai et al. noted that miR-200c/ZNF217/TGF-β/ZEB1, an expansile regulatory loop of the miR-200c/ZEB1 negative feedback circuit, synergistically increased trastuzumab sensitivity and suppressed the invasive abilities of breast cancer cells [50]. In this circuit, miR-200c suppressed the transcription factor ZNF217, which can promote the autocrine process of TGF-β; correspondingly, TGF-β signaling further transcriptionally activated ZEB1 to exhibit feedback suppression on the expression of miR-200c [49, 89].

β-catenin/TCF4 was also involved in chemoresistance through activating the transcriptional activities of ZEB1 [14, 60]. The nuclear accumulation of β-catenin was induced by Axl-activated Akt/GSK3β/β-catenin signaling, followed by a direct transcriptional increase in ZEB1, which in turn mediated DDR and doxorubicin resistance in breast cancer cells; these results suggest that the important function of Akt/GSK3β/β-catenin/ZEB1 signaling is downstream of Axl-mediated drug resistance [60].

Radiation resistance

Radiotherapy is one of the major modalities of cancer treatment. A main reason for the failure of radiation therapy is intrinsic and therapy-induced radioresistant tumor cells, which display an enhanced DNA repair ability [90]. Although rare studies demonstrated the relationship between ZEB1 and radioresistance, the results still promoted corresponding scientific ideas to settle the problems caused by radiation resistance.

ZEB1 was identified to be phosphorylated and stabilized by ATM after ionizing radiation treatment in breast cancer cells, and correspondingly, the upregulation of ZEB1 was proven to stabilize checkpoint kinase 1 (CHK1) by activating the deubiquitylation of ubiquitin-specific-processing protease 7 (USP7), thus promoting homologous recombination-dependent DNA repair and resulting in radioresistance [43]. This study provided a potential mechanism for ZEB1 function in radioresistance, that is, ZEB1 was phosphorylated and stabilized by ATM depending on irradiation, which in turn repressed its negative regulator, miR-205, resulting in a further increase in ZEB1; these effects were followed by increased ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc13 levels and improved DDR, finally inducing radioresistance. Moreover, DDR was inhibited by miR-205 via targeting ZEB1 and Ubc13. Not surprisingly, targeting-ZEB1 agents, such as the miR-205 mimics, were supposed to be potential radiosensitizing agents, revealing a new therapeutic strategy for radioresistant tumors [91].

On the other hand, as ZEB1 was identified as a downstream target of miR-205, the expression level of miR-205 can be inhibited by nuclear enriched abundant transcript 1 (NEAT1), which regulates EMT progress and radioresistance in nasopharyngeal carcinoma [92]. Concerning the response of identified cancer cells to radiation, it is suggested that ZEB1 may both hinder the formation of oncogene-induced DNA damage by inhibiting oxidative stress and promote the clearance of DNA breaks by activating DDR, protecting cancer cells for survival [16].

Conclusion

In recent decades, the understanding of the molecular mechanism of ZEB1 in cancer progression has greatly improved (Fig. 3). Accumulated evidence indicates that ZEB1 displays a broad spectrum of biological functions. Elevated expression of ZEB1 not only increases cell motility and invasiveness by downregulating epithelial markers and upregulating mesenchymal markers but also contributes stem cell-like features to tumor cells, providing resistance to various types of therapy. Therefore, the expression of ZEB1 may be a biomarker of poor clinical outcomes for cancer patients. The recent recognition of the regulation and functions of ZEB1 has shed new light on understanding its potential clinical and therapeutic implications in cancers.

The main targets of ZEB1 and the processes involved in breast cancers. Cyclin-dependent protein kinase-like 2(CDKL2) transcriptionally activates ZEB1 and suppresses E-cadherin to promote the EMT process. The carcinogenesis-related CSC state is determined by the CD44s isoform conserved by CD44v and controlled by epithelial splicing regulatory protein 1 (ESRP1). The transcriptional suppression of downstream LLGL1/2 by ZEB1 is associated with apical-basal polarity, and inhibition of ER-α by ZEB1 regulates the sensitivities to antiestrogen treatment in breast cancer. However, ZEB1 also transcriptionally activates the expression of ATM kinase and promotes the occurrence of chemoresistance

Despite these developments, much remains unknown about the role of ZEB1 in metastasis, a complex and multistep process where cancer cells hijack the normal developmental networks for tumor progression and metastasis. Within the complex signaling networks, ZEB1 is regulated through signal integration, crosstalk and feedback control. It is often difficult to identify whether a particular molecule or pathway under investigation is specific to ZEB1-mediated EMT. Therefore, further investigations to reveal the contribution of various tumor microenvironmental factors to tumor progression will lead to a comprehensive understanding of ZEB1 in cancer.

Recent studies have shown that the suppression of the miR-200 family by ZEB1 results in the upregulation of programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-L1), which is related to the immune system [93], suggesting that the ZEB1/miR-200 axis could influence the immune recognition of cancer cells. Therefore, in addition to normal treatments for cancers, the exploration of ZEB1 in immunotherapy has provided new potential and effective therapeutic strategies for metastatic breast cancers.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ATM:

-

Ataxia-telangiectasia mutated kinase

- AXL:

-

AXL receptor tyrosine kinase

- BET:

-

Bromodomain and extra-terminal

- bHLH:

-

Basic helix-loop-helix

- CBS:

-

Cascading bistable switches

- CDKL2:

-

Cyclin-dependent protein kinase-like 2

- CHK1:

-

Checkpoint kinase 1

- CSC:

-

Cancer stem cells

- CTGF:

-

Connective tissue growth factor

- CZF:

-

C-terminal cluster

- DDR:

-

DNA damage repair

- DNMT3B:

-

DNA methyltransferase 3B

- EMT:

-

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- EPI:

-

Epirubicin

- ER-α:

-

Estrogen receptor-alpha

- ESRPs:

-

Epithelial splicing regulatory proteins

- HD:

-

Homeodomain

- HDAC1:

-

Histone deacetylase 1

- HER2:

-

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- HNK:

-

Honokiol

- HR:

-

Homologous recombination

- IGF1:

-

Insulin-like growth factor-1

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- LLGL1/2:

-

Lethal giant larvae homolog 1/2

- NEAT1:

-

Nuclear enriched abundant transcript 1

- NZF:

-

N-terminal cluster

- PCAF:

-

P300/CBP-associated factor

- PD-L1:

-

Programmed cell death protein 1

- PROTAC:

-

Proteolysis targeting chimeric

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- STAT:

-

Signal transducer and activator of transcription

- SWI/SNF:

-

Yeast mating-type switching/sucrose nonfermenting

- TCS:

-

Ternary chimera switch

- TGF:

-

Transforming growth factor

- TNBC:

-

Triple-negative breast cancers

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- USP7:

-

Ubiquitin-specific-processing protease 7

- UTR:

-

Untranslated region

- VM:

-

Vascular mimicry

- YAP:

-

Yes-associated protein

- ZEB:

-

Zinc finger E-box binding homeobox

- ZNF:

-

Zinc finger protein

References

Hay ED. An overview of epithelio-mesenchymal transformation. Acta Anat. 1995;154:8–20.

Lamouille S, Xu J, Derynck R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:178–96.

Grooteclaes ML, Frisch SM. Evidence for a function of CtBP in epithelial gene regulation and anoikis. Oncogene. 2000;19:3823–8.

Comijn J, Berx G, Vermassen P, Verschueren K, van Grunsven L, Bruyneel E, Mareel M, Huylebroeck D, van Roy F. The two-handed E box binding zinc finger protein SIP1 downregulates E-cadherin and induces invasion. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1267–78.

Cano A, Perez-Moreno MA, Rodrigo I, Locascio A, Blanco MJ, del Barrio MG, Portillo F, Nieto MA. The transcription factor snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:76–83.

Perez-Moreno MA, Locascio A, Rodrigo I, Dhondt G, Portillo F, Nieto MA, Cano A. A new role for E12/E47 in the repression of E-cadherin expression and epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:27424–31.

Yang S, Zhao L, Yang J, Chai D, Zhang M, Zhang J, Ji X, Zhu T. deltaEF1 represses BMP-2-induced differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts into the osteoblast lineage. J Biomed Sci. 2007;14:663–79.

Ponticos M, Partridge T, Black CM, Abraham DJ, Bou-Gharios G. Regulation of collagen type I in vascular smooth muscle cells by competition between Nkx2.5 and deltaEF1/ZEB1. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6151–61.

Singh S, Howell D, Trivedi N, Kessler K, Ong T, Rosmaninho P, Raposo AA, Robinson G, Roussel MF, Castro DS, Solecki DJ. Zeb1 controls neuron differentiation and germinal zone exit by a mesenchymal-epithelial-like transition. ELife. 2016;5:e12717.

Eger A, Aigner K, Sonderegger S, Dampier B, Oehler S, Schreiber M, Berx G, Cano A, Beug H, Foisner R. DeltaEF1 is a transcriptional repressor of E-cadherin and regulates epithelial plasticity in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:2375–85.

Gregory PA, Bert AG, Paterson EL, Barry SC, Tsykin A, Farshid G, Vadas MA, Khew-Goodall Y, Goodall GJ. The miR-200 family and miR-205 regulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:593–601.

Aghdassi A, Sendler M, Guenther A, Mayerle J, Behn CO, Heidecke CD, Friess H, Buchler M, Evert M, Lerch MM, Weiss FU. Recruitment of histone deacetylases HDAC1 and HDAC2 by the transcriptional repressor ZEB1 downregulates E-cadherin expression in pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2012;61:439–48.

Yang Y, Ahn YH, Chen Y, Tan X, Guo L, Gibbons DL, Ungewiss C, Peng DH, Liu X, Lin SH, et al. ZEB1 sensitizes lung adenocarcinoma to metastasis suppression by PI3K antagonism. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:2696–708.

Wang Y, Bu F, Royer C, Serres S, Larkin JR, Soto MS, Sibson NR, Salter V, Fritzsche F, Turnquist C, et al. ASPP2 controls epithelial plasticity and inhibits metastasis through beta-catenin-dependent regulation of ZEB1. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:1092–104.

Wang Y, Wen M, Kwon Y, Xu Y, Liu Y, Zhang P, He X, Wang Q, Huang Y, Jen KY, et al. CUL4A induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and promotes cancer metastasis by regulating ZEB1 expression. Cancer Res. 2014;74:520–31.

Morel AP, Ginestier C, Pommier RM, Cabaud O, Ruiz E, Wicinski J, Devouassoux-Shisheboran M, Combaret V, Finetti P, Chassot C, et al. A stemness-related ZEB1-MSRB3 axis governs cellular pliancy and breast cancer genome stability. Nat Med. 2017;23:568–78.

Wang C, Jin H, Wang N, Fan S, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Wei L, Tao X, Gu D, Zhao F, et al. Gas6/Axl axis contributes to chemoresistance and metastasis in breast cancer through Akt/GSK-3beta/beta-catenin signaling. Theranostics. 2016;6:1205–19.

Funahashi J, Kamachi Y, Goto K, Kondoh H. Identification of nuclear factor delta EF1 and its binding site essential for lens-specific activity of the delta 1-crystallin enhancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:3543–7.

Funahashi J, Sekido R, Murai K, Kamachi Y, Kondoh H. Delta-crystallin enhancer binding protein delta EF1 is a zinc finger-homeodomain protein implicated in postgastrulation embryogenesis. Development. 1993;119:433–46.

Takagi T, Moribe H, Kondoh H, Higashi Y. DeltaEF1, a zinc finger and homeodomain transcription factor, is required for skeleton patterning in multiple lineages. Development. 1998;125:21–31.

Karihtala P, Auvinen P, Kauppila S, Haapasaari KM, Jukkola-Vuorinen A, Soini Y. Vimentin, zeb1 and Sip1 are up-regulated in triple-negative and basal-like breast cancers: association with an aggressive tumour phenotype. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138:81–90.

Lehmann W, Mossmann D, Kleemann J, Mock K, Meisinger C, Brummer T, Herr R, Brabletz S, Stemmler MP, Brabletz T. ZEB1 turns into a transcriptional activator by interacting with YAP1 in aggressive cancer types. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10498.

Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–90.

Yu Y, Luo W, Yang ZJ, Chi JR, Li YR, Ding Y, Ge J, Wang X, Cao XC. miR-190 suppresses breast cancer metastasis by regulation of TGF-beta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Mol Cancer. 2018;17:70.

Burk U, Schubert J, Wellner U, Schmalhofer O, Vincan E, Spaderna S, Brabletz T. A reciprocal repression between ZEB1 and members of the miR-200 family promotes EMT and invasion in cancer cells. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:582–9.

Bracken CP, Gregory PA, Kolesnikoff N, Bert AG, Wang J, Shannon MF, Goodall GJ. A double-negative feedback loop between ZEB1-SIP1 and the microRNA-200 family regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7846–54.

Gheldof A, Hulpiau P, van Roy F, De Craene B, Berx G. Evolutionary functional analysis and molecular regulation of the ZEB transcription factors. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:2527–41.

Kim JH, Cho EJ, Kim ST, Youn HD. CtBP represses p300-mediated transcriptional activation by direct association with its bromodomain. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:423–8.

Chaffer CL, Marjanovic ND, Lee T, Bell G, Kleer CG, Reinhardt F, D’Alessio AC, Young RA, Weinberg RA. Poised chromatin at the ZEB1 promoter enables breast cancer cell plasticity and enhances tumorigenicity. Cell. 2013;154:61–74.

Guenther MG, Levine SS, Boyer LA, Jaenisch R, Young RA. A chromatin landmark and transcription initiation at most promoters in human cells. Cell. 2007;130:77–88.

Mueller D, Bach C, Zeisig D, Garcia-Cuellar MP, Monroe S, Sreekumar A, Zhou R, Nesvizhskii A, Chinnaiyan A, Hess JL, Slany RK. A role for the MLL fusion partner ENL in transcriptional elongation and chromatin modification. Blood. 2007;110:4445–54.

Cao R, Wang L, Wang H, Xia L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Jones RS, Zhang Y. Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group silencing. Science. 2002;298:1039–43.

Czermin B, Melfi R, McCabe D, Seitz V, Imhof A, Pirrotta V. Drosophila enhancer of Zeste/ESC complexes have a histone H3 methyltransferase activity that marks chromosomal Polycomb sites. Cell. 2002;111:185–96.

Kuzmichev A, Nishioka K, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Reinberg D. Histone methyltransferase activity associated with a human multiprotein complex containing the Enhancer of Zeste protein. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2893–905.

Muller J, Hart CM, Francis NJ, Vargas ML, Sengupta A, Wild B, Miller EL, O’Connor MB, Kingston RE, Simon JA. Histone methyltransferase activity of a Drosophila Polycomb group repressor complex. Cell. 2002;111:197–208.

Caramel J, Ligier M, Puisieux A. Pleiotropic Roles for ZEB1 in Cancer. Cancer Res. 2018;78:30–5.

Avtanski DB, Nagalingam A, Bonner MY, Arbiser JL, Saxena NK, Sharma D. Honokiol inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer cells by targeting signal transducer and activator of transcription 3/Zeb1/E-cadherin axis. Mol Oncol. 2014;8:565–80.

Llorens MC, Lorenzatti G, Cavallo NL, Vaglienti MV, Perrone AP, Carenbauer AL, Darling DS, Cabanillas AM. Phosphorylation regulates functions of ZEB1 transcription factor. J Cell Physiol. 2016;231:2205–17.

Long J, Zuo D, Park M. Pc2-mediated sumoylation of Smad-interacting protein 1 attenuates transcriptional repression of E-cadherin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:35477–89.

Lambies G. Garcia de Herreros A, Diaz VM: The role of DUBs in the post-translational control of cell migration. Essays Biochem. 2019;63:579–94.

Zhou Z, Zhang P, Hu X, Kim J, Yao F, Xiao Z, Zeng L, Chang L, Sun Y, Ma L. USP51 promotes deubiquitination and stabilization of ZEB1. Am J Cancer Res. 2017;7:2020–31.

Zhang S, Hong Z, Chai Y, Liu Z, Du Y, Li Q, Liu Q. CSN5 promotes renal cell carcinoma metastasis and EMT by inhibiting ZEB1 degradation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;488:101–8.

Zhang P, Wei Y, Wang L, Debeb BG, Yuan Y, Zhang J, Yuan J, Wang M, Chen D, Sun Y, et al. ATM-mediated stabilization of ZEB1 promotes DNA damage response and radioresistance through CHK1. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:864–75.

Christoffersen NR, Silahtaroglu A, Orom UA, Kauppinen S, Lund AH. miR-200b mediates post-transcriptional repression of ZFHX1B. RNA. 2007;13:1172–8.

Hurteau GJ, Carlson JA, Spivack SD, Brock GJ. Overexpression of the microRNA hsa-miR-200c leads to reduced expression of transcription factor 8 and increased expression of E-cadherin. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7972–6.

Brabletz S, Brabletz T. The ZEB/miR-200 feedback loop–a motor of cellular plasticity in development and cancer? EMBO Rep. 2010;11:670–7.

Koh M, Woo Y, Valiathan RR, Jung HY, Park SY, Kim YN, Kim HR, Fridman R, Moon A. Discoidin domain receptor 1 is a novel transcriptional target of ZEB1 in breast epithelial cells undergoing H-Ras-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E508–20.

Massague J. TGF beta in cancer. Cell. 2008;134:215–30.

Vendrell JA, Thollet A, Nguyen NT, Ghayad SE, Vinot S, Bieche I, Grisard E, Josserand V, Coll JL, Roux P, et al. ZNF217 is a marker of poor prognosis in breast cancer that drives epithelial-mesenchymal transition and invasion. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3593–606.

Bai WD, Ye XM, Zhang MY, Zhu HY, Xi WJ, Huang X, Zhao J, Gu B, Zheng GX, Yang AG, Jia LT. MiR-200c suppresses TGF-beta signaling and counteracts trastuzumab resistance and metastasis by targeting ZNF217 and ZEB1 in breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:1356–68.

Hugo HJ, Pereira L, Suryadinata R, Drabsch Y, Gonda TJ, Gunasinghe NP, Pinto C, Soo ET, van Denderen BJ, Hill P, et al. Direct repression of MYB by ZEB1 suppresses proliferation and epithelial gene expression during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15:R113.

Cieply B, Riley PT, Pifer PM, Widmeyer J, Addison JB, Ivanov AV, Denvir J, Frisch SM. Suppression of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition by Grainyhead-like-2. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2440–53.

Cieply B, Farris J, Denvir J, Ford HL, Frisch SM. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumor suppression are controlled by a reciprocal feedback loop between ZEB1 and Grainyhead-like-2. Cancer Res. 2013;73:6299–309.

Trimboli AJ, Fukino K, de Bruin A, Wei G, Shen L, Tanner SM, Creasap N, Rosol TJ, Robinson ML, Eng C, et al. Direct evidence for epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:937–45.

Ponta H, Sherman L, Herrlich PA. CD44: from adhesion molecules to signalling regulators. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:33–45.

Preca BT, Bajdak K, Mock K, Sundararajan V, Pfannstiel J, Maurer J, Wellner U, Hopt UT, Brummer T, Brabletz S, et al. A self-enforcing CD44s/ZEB1 feedback loop maintains EMT and stemness properties in cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:2566–77.

Kim JH, Moon MJ, Kim DY, Heo SH, Jeong YY. Hyaluronic acid-based nanomaterials for cancer therapy. Polymers. 2018;10:1133.

Preca BT, Bajdak K, Mock K, Lehmann W, Sundararajan V, Bronsert P, Matzge-Ogi A, Orian-Rousseau V, Brabletz S, Brabletz T, et al. A novel ZEB1/HAS2 positive feedback loop promotes EMT in breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:11530–43.

Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ. Cancer stem cells: current status and evolving complexities. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:717–28.

Sanchez-Tillo E, de Barrios O, Siles L, Cuatrecasas M, Castells A, Postigo A. beta-catenin/TCF4 complex induces the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)-activator ZEB1 to regulate tumor invasiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:19204–9.

Zeisberg M, Neilson EG. Biomarkers for epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1429–37.

Horiguchi K, Sakamoto K, Koinuma D, Semba K, Inoue A, Inoue S, Fujii H, Yamaguchi A, Miyazawa K, Miyazono K, Saitoh M. TGF-beta drives epithelial-mesenchymal transition through delta EF1-mediated downregulation of ESRP. Oncogene. 2012;31:3190–201.

Brown RL, Reinke LM, Damerow MS, Perez D, Chodosh LA, Yang J, Cheng C. CD44 splice isoform switching in human and mouse epithelium is essential for epithelial-mesenchymal transition and breast cancer progression. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1064–74.

Shapiro IM, Cheng AW, Flytzanis NC, Balsamo M, Condeelis JS, Oktay MH, Burge CB, Gertler FB. An EMT-driven alternative splicing program occurs in human breast cancer and modulates cellular phenotype. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002218.

Li L, Liu C, Amato RJ, Chang JT, Du G, Li W. CDKL2 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and breast cancer progression. Oncotarget. 2014;5:10840–53.

Schmalhofer O, Brabletz S, Brabletz T. E-cadherin, beta-catenin, and ZEB1 in malignant progression of cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:151–66.

Lu M, Jolly MK, Levine H, Onuchic JN, Ben-Jacob E. MicroRNA-based regulation of epithelial-hybrid-mesenchymal fate determination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:18144–9.

Zhang J, Tian XJ, Zhang H, Teng Y, Li R, Bai F, Elankumaran S, Xing J. TGF-beta-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition proceeds through stepwise activation of multiple feedback loops. Sci Signal. 2014;7:ra91.

Saito Y, Li L, Coyaud E, Luna A, Sander C, Raught B, Asara JM, Brown M, Muthuswamy SK. LLGL2 rescues nutrient stress by promoting leucine uptake in ER(+) breast cancer. Nature. 2019;569:275–9.

Chao CH, Chang CC, Wu MJ, Ko HW, Wang D, Hung MC, Yang JY, Chang CJ. MicroRNA-205 signaling regulates mammary stem cell fate and tumorigenesis. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:3093–106.

Aigner K, Dampier B, Descovich L, Mikula M, Sultan A, Schreiber M, Mikulits W, Brabletz T, Strand D, Obrist P, et al. The transcription factor ZEB1 (deltaEF1) promotes tumour cell dedifferentiation by repressing master regulators of epithelial polarity. Oncogene. 2007;26:6979–88.

Wu Q, Xiang S, Ma J, Hui P, Wang T, Meng W, Shi M, Wang Y. Long non-coding RNA CASC15 regulates gastric cancer cell proliferation, migration and epithelial mesenchymal transition by targeting CDKN1A and ZEB1. Mol Oncol. 2018;16:799–813.

Sangrador I, Molero X, Campbell F, Franch-Exposito S, Rovira-Rigau M, Samper E, Dominguez-Fraile M, Fillat C, Castells A, Vaquero EC. Zeb1 in stromal myofibroblasts promotes kras-driven development of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2018;78:2624–37.

Barbachano A, Fernandez-Barral A, Pereira F, Segura MF, Ordonez-Moran P, Carrillo E, Gonzalez-Sancho JM, Hanniford D, Martinez N, Costales-Carrera A, et al. SPROUTY-2 represses the epithelial phenotype of colon carcinoma cells via upregulation of ZEB1 mediated by ETS1 and miR-200/miR-150. Oncogene. 2016;35:2991–3003.

Guo X, Zhao L, Cheng D, Mu Q, Kuang H, Feng K. AKIP1 promoted epithelial-mesenchymal transition of non-small-cell lung cancer via transactivating ZEB1. Am J Cancer Res. 2017;7:2234–44.

Meng X, Kong DH, Li N, Zong ZH, Liu BQ, Du ZX, Guan Y, Cao L, Wang HQ. Knockdown of BAG3 induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition in thyroid cancer cells through ZEB1 activation. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1092.

Zhang X, Zhang Z, Zhang Q, Zhang Q, Sun P, Xiang R, Ren G, Yang S. ZEB1 confers chemotherapeutic resistance to breast cancer by activating ATM. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:57.

Katsura A, Tamura Y, Hokari S, Harada M, Morikawa M, Sakurai T, Takahashi K, Mizutani A, Nishida J, Yokoyama Y, et al. ZEB1-regulated inflammatory phenotype in breast cancer cells. Mol Oncol. 2017;11:1241–62.

Fu R, Han CF, Ni T, Di L, Liu LJ, Lv WC, Bi YR, Jiang N, He Y, Li HM, et al. A ZEB1/p53 signaling axis in stromal fibroblasts promotes mammary epithelial tumours. Nat Commun. 2019;10:3210.

Langer EM, Kendsersky ND, Daniel CJ, Kuziel GM, Pelz C, Murphy KM, Capecchi MR, Sears RC. ZEB1-repressed microRNAs inhibit autocrine signaling that promotes vascular mimicry of breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2018;37:1005–19.

Chen H, Lu W, Huang C, Ding K, Xia D, Wu Y, Cai M. Prognostic significance of ZEB1 and ZEB2 in digestive cancers: a cohort-based analysis and secondary analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:31435–48.

Holohan C, Van Schaeybroeck S, Longley DB, Johnston PG. Cancer drug resistance: an evolving paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:714–26.

Camidge DR, Pao W, Sequist LV. Acquired resistance to TKIs in solid tumours: learning from lung cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11:473–81.

Baumann M, Krause M, Hill R. Exploring the role of cancer stem cells in radioresistance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:545–54.

Siebzehnrubl FA, Silver DJ, Tugertimur B, Deleyrolle LP, Siebzehnrubl D, Sarkisian MR, Devers KG, Yachnis AT, Kupper MD, Neal D, et al. The ZEB1 pathway links glioblastoma initiation, invasion and chemoresistance. EMBO Mol Med. 2013;5:1196–212.

Zheng G, Peng C, Jia X, Gu Y, Zhang Z, Deng Y, Wang C, Li N, Yin J, Liu X, et al. ZEB1 transcriptionally regulated carbonic anhydrase 9 mediates the chemoresistance of tongue cancer via maintaining intracellular pH. Mol Cancer. 2015;14:84.

Dou XW, Liang YK, Lin HY, Wei XL, Zhang YQ, Bai JW, Chen CF, Chen M, Du CW, Li YC, et al. Notch3 maintains luminal phenotype and suppresses tumorigenesis and metastasis of breast cancer via trans-activating estrogen receptor-alpha. Theranostics. 2017;7:4041–56.

Esteva FJ, Valero V, Booser D, Guerra LT, Murray JL, Pusztai L, Cristofanilli M, Arun B, Esmaeli B, Fritsche HA, et al. Phase II study of weekly docetaxel and trastuzumab for patients with HER-2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1800–8.

Dave N, Guaita-Esteruelas S, Gutarra S, Frias A, Beltran M, Peiro S, de Herreros AG. Functional cooperation between Snail1 and twist in the regulation of ZEB1 expression during epithelial to mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:12024–32.

Jameel JK, Rao VS, Cawkwell L, Drew PJ. Radioresistance in carcinoma of the breast. Breast. 2004;13:452–60.

Zhang P, Wang L, Rodriguez-Aguayo C, Yuan Y, Debeb BG, Chen D, Sun Y, You MJ, Liu Y, Dean DC, et al. miR-205 acts as a tumour radiosensitizer by targeting ZEB1 and Ubc13. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5671.

Lu Y, Li T, Wei G, Liu L, Chen Q, Xu L, Zhang K, Zeng D, Liao R. The long non-coding RNA NEAT1 regulates epithelial to mesenchymal transition and radioresistance in through miR-204/ZEB1 axis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:11733–41.

Toneff MJ, Sreekumar A, Tinnirello A, Hollander PD, Habib S, Li S, Ellis MJ, Xin L, Mani SA, Rosen JM. The Z-cad dual fluorescent sensor detects dynamic changes between the epithelial and mesenchymal cellular states. BMC Biol. 2016;14:47.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Dr. Yi-Teng Huang for his valuable advice and English editing.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81501539 and 81320108015), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. 2016A030312008), and the Li Ka Shing Foundation Grant for Joint Research Program between Shantou University and Technion-Israel Institute of Technology (No. 43209501).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JL contributed to the conception and design of the study. HW, HZ and JL organized the database, searched the literature, structured and carefully drafted the manuscript. GL, JS, QY and MZ analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted and revised carefully the manuscript. JL critically revised the original manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, HT., Zhong, HT., Li, GW. et al. Oncogenic functions of the EMT-related transcription factor ZEB1 in breast cancer. J Transl Med 18, 51 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-020-02240-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-020-02240-z