Abstract

Background

Gastrointestinal microbiome has drawn an increasing amount of attention over the past decades. There is emerging evidence that the gut flora plays a major role in the pathogenesis of certain diseases. We aimed to analyze the evolution of gastrointestinal microbiome research and evaluate publications qualitatively and quantitatively.

Methods

We obtained a record of 2891 manuscripts published between 1998 and 2018 from the Web of Science Core Collection (WoSCC) of Thomson Reuters; this record was obtained on June 23, 2018. The WoSCC is the most frequently used source of scientific information. We used the term “Gastrointestinal Microbiomes” and all of its hyponyms to retrieve the record, and restricted the subjects to gastroenterology and hepatology. We then derived a clustered network from 70,169 references that were cited by the 2891 manuscripts, and identified 676 top co-cited articles. Next, we used the bibliometric method, CiteSpace V, and VOSviewer 1.6.8 to identify top authors, journals, institutions, countries, keywords, co-cited articles, and trends.

Results

We identified that the number of publications on gastrointestinal microbiome is increasing over time. 112 journals published articles on gastrointestinal microbiome. The United States of America was the leading country for publications, and the leading institution was the University of North Carolina. Co-cited reference analysis revealed the top landmark articles in the field. Gut microbiota, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), probiotics, irritable bowel disease, and obesity are some of the high frequency keywords in co-occurrence cluster analysis and co-cited reference cluster analysis; indicating gut microbiota and related digestive diseases remain the hotspots in gut microbiome research. Burst detection analysis of top keywords showed that bile acid, obesity, and Akkermansia muciniphila were the new research foci.

Conclusions

This study revealed that our understanding of the link between gastrointestinal microbiome and associated diseases has evolved dramatically over time. The emerging new therapeutic targets in gut microbiota would be the foci of future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The human gastrointestinal flora is an essential organ that plays an important role in gastrointestinal and overall health. Understanding of this organ has evolved significantly over the past decades due to the large quantity of impactful research on the gastrointestinal microbiome.

Since the 1990s, the development of culture independent molecular methods, including 16S ribosomal RNA (16S rRNA) gene sequencing and metagenomic sequencing methods, has allowed for quantitative analysis of the composites of gut microbiome and provided a better understanding of its variation and function. 16S rRNA genes are bacteria’s small subunit molecules that include both conserved and variable regions that allow designing probes or primers to detect and identify bacteria, and specify a phylum, a group, a genus, or even a species [1]. This technique has increased previous culture-based estimates of 200–300 colonic species to 15,000–36,000 individual species [2]. Metagenomic sequencing represents a powerful alternative to rRNA sequencing, it utilizes taxonomically informative gene tags to target and amplify genomes of interest, analysis of this data allows researchers to determine the composite and function of different microbiomes, it is widely used for global characterization of the genetic potential of ecologically complex environments [3, 4].

The human metagenome is composed of Homo sapiens genes and genes present in the genome of the microbes that colonize the human body, estimates have the latter as encoding 100-fold more unique genes than the human genome [5, 6]. The majority of the colonizing microbes reside in the gut. Previous study revealed that there is a functional core conserved in each individual, which represents the full minimal human gut metagenome that is required for the proper functioning of the gut ecosystem. The human gut ecosystem includes important beneficial functions, such as: fermentation of dietary fibers into short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) which counts up to 10% of the human energy source, degradation of complex polysaccharides, and synthesis of indispensable vitamins and amino acids [4, 6,7,8]. The gut flora also produce multiple metabolites that function in protecting epithelial lining integrity, stimulating intestinal angiogenesis, and regulating immune response [9,10,11]. These reflect that gut flora are not just commensal with human hosts, there is mutualism in the relationship between them.

Sampling is a key step for studies on gut microbiome. A significant number of studies are human based, while most others are mice based. Fewer studies were performed on gut microbiota from tissue samples, while most others were performed on fecal microbiota. In different regions of the gastrointestinal tract, the composition and luminal concentrations of dominant microbial species vary; the distal ileum, cecum, and colon are the most common sites for tissue sample harvesting due to high quantity and variety of gut flora in these regions [3, 12, 13]. Fecal samples are often used to investigate mucosa-associated microbiota because they are easy to collect, noninvasive, are approved to be a reproducible and relevant source of biomarkers [1]. But there is still concern that the fecal microbiota may represent a combination of shed mucosal bacteria and a separate nonadherent luminal population, thus making the result less reliable [13].

Over 98% of the gut microbiota is composed of four phyla of bacteria: Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria. The dominant majority are from either Firmicutes or Bacteroidetes [2, 13]. Gut microbiota composition varies based on sampling region. Research has revealed that the Bacillus subgroup of Firmicutes and Actinobacteria are more prevalent in the small intestine, while Bacteroidetes and Lachnospiraceae are more prevalent in the colon [2]. Human gut microbiome is more similar among family members than unrelated individuals; intra-personal differences are minor compared to inter-personal differences in gut microbiota, indicating short term environmental change does not play a major part in microbiota composition [14].

The proper interaction between host gut mucosa and gut microbiota is important in maintaining mucosal homeostasis. The gut microbiota is proposed to shape host immunity and host immunity functions via secreting molecules that protect the mucosal barrier integrity, proper secretion of luminal antimicrobial peptides and immunoglobulins, down-regulation of innate and adaptive immune responses to commensal bacteria, and elimination of translocated bacteria across epithelial barrier [8, 11, 15]. Mucosal homeostasis is key to both host and gut flora and can be disrupted in dysbiosis causing chronic intestinal inflammation.

CiteSpace is an application designed to generate and analyze networks of co-cited references based on bibliographic database [16]. We employed this method to analyze trends and hotspots of global publications on gastrointestinal microbiome between 1998 and 2018.

Methods

We obtained a record of 2891 manuscripts published between 1998 and 2018 from the Web of Science Core Collection (WoSCC) of Thomson Reuters; this record was obtained on June 23, 2018. The WoSCC is the most frequently used source of scientific information. We used the term “Gastrointestinal Microbiomes” and all of its hyponyms to retrieve the record, and restricted the subjects to gastroenterology and hepatology. We then derived a clustered network from 70,169 references that were cited by the 2891 manuscripts, and identified 676 top co-cited articles. Next, we used the bibliometric method, CiteSpace V, and VOSviewer 1.6.8 to identify top authors, journals, institutions, countries, keywords, co-cited articles, and trends.

Results

Distribution of articles by publication years

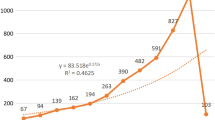

Between 1998 and 2018, 2891 original research articles were published. There was an increasing trend for quantity of research publications on gastrointestinal microbiome (Fig. 1). The number of published articles on gastrointestinal microbiome steadily increased from 1998 through 2009, and then the number of publications significantly increased from 2010 onwards, with the number of publications almost doubled in 2014 compared to 2010. During 2016 through 2017, the activity in gut microbiome research reached a peak.

Journal analysis

The total number of journals that published the 2891 articles on gastrointestinal microbiome was 112. The characteristics of the 10 most active journals and the main ideas of their representative articles are shown in Table 1 [1, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. All the publishers of the journals are located in either the United States of America or the United Kingdom. Digestive Diseases and Sciences published the greatest number of articles on gut microbiome, followed by World Journal of Gastroenterology and Gut. Regarding impact factor, Gastroenterology has the highest impact factor, followed by Gut and Alimentary Pharmacology Therapeutics.

Country and institution analysis

The 2891 articles on gastrointestinal microbiome research were published by research groups in 41 countries/regions. The top 10 countries (6 European countries, 2 Asian countries, and 2 North American countries) published 2692 articles, accounting for 93.12% of the total number of publications. The leading country was the United States, which took up 31.92% (923/2891) of the total, the next 2 high production countries were Italy and the People’s Republic of China, which took up 10% and 8% of the total, respectively. There were more than 370 research institutions that published articles related to gut microbiome. The leading research institution with the highest number of publications was the University of North Carolina, which had 64 articles with the strongest citation burst from 2003 to 2011, followed by Harvard University (53 articles), Mayo Clinic (41 articles), French National Institute for Agricultural Research (40 articles), and Massachusetts General Hospital (39 articles).

Keyword co-occurrence cluster analysis of research hotspots

VOSviewer keyword analysis of the 2891 articles identified 274 keywords with a minimum of 20 occurrences and divided them into 5 clusters (Gut microbiota, IBD, probiotics, double-blind, and irritable bowel syndrome) (Fig. 2).

Top co-cited articles analysis

The clustered network is derived from 70,169 references (including duplicates) that were cited by the 2891 articles. The clustered network of gastrointestinal microbiome is demonstrated in this part. Citation reference knowledge maps consist of references with higher centrality and citation counts. Visualization of co-cited articles showed a total of 676 nodes and 1427 links (Fig. 3a). Each node represents a cited article. The area of each node is proportional to the total co-citation frequency of the associated article.

The top 10 co-cited articles, their cited frequency, and cited half-year life are shown in Table 2. Sokol [12] in PNAS had the highest number of citations (168 citations), followed by Caporaso [17] in Nature Methods (163 citations), and Qin [4] in Nature (148 citations). These articles are often considered fundamental in gastrointestinal microbiome research.

Co-cited reference cluster analysis

To detect research hotspots, we mapped the 676 top co-cited articles cited by 2891 original articles via a clustered network in hierarchical order (Fig. 3b). The nodes represent different cited references and the clusters represent a distinct specialty or a thematic concentration. The citation reference knowledge map consists of references with higher centrality and citation counts. The area of each node is proportional to the total co-citation frequency of the associated reference. The co-cited references could be clustered into eleven main sub-clusters including obesity, irritable bowel syndrome, IBD, innate immunity, probiotics, etc. Figure 4 displays a timeline visualization of distinct co-citation and shows that Cluster #0 obesity and Cluster #2 Faecalibacterium prausnitzii had the highest concentration of nodes with citation bursts, and research foci seems to have shifted from IBD to obesity and cirrhosis. This supports the finding of the emerging focus in gut microbiome.

Burst detection

Burst detection identified articles that have attracted the attention of peer researchers. We detected bursts between 1998 through 2018 based on analysis of the 2891 original articles. The timeline is depicted as a blue line, and the time interval that a subject was found to have a burst is shown as a red segment on the blue timeline, indicating the beginning year, the ending year, and the duration of the burst. Among the top 191 keywords with the highest burst strength, we were particularly interested in those keywords with research significance which indicate the evolution trend of the gut microbiome (Fig. 5). During the entire time period from 1998 through 2018, dysbiosis had the highest burst strength, followed by Clostridium difficile infection, 16s rRNA, Interleukin 10 deficient mice, and fecal microbiota transplantation. Interleukin 10 deficient mice, bacterial translocation and overgrowth, and mesenteric lymph node became the research foci since 1998 and then the intestinal epithelial cell; 16s rRNA sequencing became a research focus since 2004, followed by toll like receptor and innate immunity, marking microbiome research entering the new era; regarding the bursts with most recent onset: bile acid, obesity, and Akkermansia muciniphila were the strongest bursts that started in 2016.

Discussion

In this study, we utilized information visualization to analyze original articles on gut microbiome published from 1998 through 2018. Based on the trends we identified that showed an increasing number of scientific research publications over the 20-year period; we conclude that gut microbiome has become a subject of growing study and an increasingly important area of research. The burst of research activity after 2010 is likely due to the fact that some research publications that have had a major impact on the understanding of gut microbiome diversity and enterotype, sequencing data analysis in microbial communities, and related digestive diseases especially IBD, and obesity were published during 2005 and 2010 (Table 2); thus, triggering researchers’ attention in this field and causing an increased number of publications.

The journals with the greatest number of articles in gut microbiome are mostly major journals in gastroenterology including Digestive Diseases and Sciences, Gastroenterology, Gut, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, World Journal of Gastroenterology, etc. This indicates that gut microbiome has become a central topic of gastroenterology research. Analysis of the co-citation map of authors and top cited authors (Fig. 3a and Table 2) during 1998 to 2018 showed that Sokol, Caporaso, Turnbaugh, Frank, Eckburg, and a few other authors are the researchers with publications that significantly impacted the research trend and current understanding of gut microbiome.

Among the top 10 co-cited articles, Caporaso et al. introduced QIIME (quantitative insights into microbial ecology), an open-source software that takes sequencing data to interpretation and database deposition, as a fundamental tool in analyzing microbial communities [26]. Eckburg et al. studied prokaryotic ribosomal RNA gene sequences from colonic mucosa tissue and feces of healthy subjects, identified the majority of bacterial phylotypes as novel or uncultivated species, and revealed significant inter-subject variability and differences between stool and adherent mucosa microbial composition, which is relevant to different sampling methods during microbiome studies [13]. Qin et al. established a catalogue of human intestinal microbial genes by using extensive illumina-based sequencing of total faecal DNA from a cohort of 124 European individuals, identified and described the minimal gut genome and metagenome in terms of functions, which is the foundation of many studies on gut microbiome function [26]. Arumugam et al. combined 22 sequenced faecal metagenomes of individuals from 4 countries with previously published datasets, identified 3 enterotypes that are geographically nonspecific, and multiple functional biomarkers for host properties including age, gender, and body mass index, which address the importance of analyzing gut microbiome function at metagenomic level [27].

Frank et al. used sequencing analysis of GI tissue samples from Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and healthy controls and studied microbiota differences between these groups. They demonstrated significant perturbations in the GI microbiotas of select IBD patients, which can be utilized as microbial markers for differentiation [2]. Sokol et al. introduced F. prausnitzii as an anti-inflammatory bacterium in Crohn’s disease population, and found that a lower proportion of F. prausnitzii on resected ileal Crohn disease mucosa was associated with endoscopic recurrence at 6 months. In vivo study on mice with induced colitis showed F. prausnitzii and its supernatant affected cytokine levels, markedly reduced the colitis severity, indicating the potential value of F. prausnitzii in Crohn’s disease treatment [12]. Sokol et al. utilized quantitative polymerase chain reaction to analyze fecal samples from subjects with active Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis in remission, infectious colitis, and healthy controls. The study showed underrepresentation of phylum Firmicutes, particularly F. prausnitzii in active IBD and infectious colitis patients, further addressing the important anti-inflammatory role of F. prausnitzii in gut inflammatory state [1]. Sartor gathered animal model evidence, clinical evidence and pathogenesis theories, extensively discussed on microbial influences on IBD and the underlying molecular mechanism, it is the most frequently cited review article in gastrointestinal microbiome [8].

Turnbaugh et al. used metagenomic analyses on mice gut microbiota model, and found that the obese microbiota is hyper-functional in harvesting energy. Transplantation of this obese microbiota resulted in increased total body fat in germ-free mice, indicating the importance of gut microbiome in the pathophysiology of obesity [3]. Turnbaugh et al. studied the faecal microbiome of adult female monozygotic and dizygotic twin pairs concordant for leanness or obesity, and their mothers, and revealed that gut microbiome is shared among family members with comparable degree of co-variation between monozygotic and dizygotic twin pairs, which adds evidence to help determine the relative contributions of host genetic vs environmental factors to gut microbial ecology. Obesity-associated gut microbial changes in diversity, community structure, and metabolic pathways were also identified, further yield association between obesity and deviation of core microbiome at a functional level [14].

The high frequency keywords including gut microbiota, IBD, irritable bowel syndrome, and probiotics in co-occurrence cluster analysis and co-cited reference cluster analysis (Figs. 2, 3b) indicate that gut microbiota and related digestive diseases, especially IBD, remained the hotspots in gut microbiome research. Analysis of top keywords, using burst detection, (Fig. 5) shows that dysbiosis, Clostridium difficile infection, and 16s rRNA attracted the most attention of peer researchers during the past 20 years, while obesity and A. muciniphila were among the new research foci since 2016. Research foci in gut microbiome seems to have shifted from IBD to obesity and liver diseases, from the traditional technique to 16s rRNA sequencing and metagenomics, and from basic science to clinical utilization.

During the past decades, a significant amount of research has been conducted to study the gut microbiota as a contributing factor to the pathogenesis of IBD. The pathogenesis of IBD has been proposed to be associated with disruption of mucosal homeostasis and dysregulation of hypersensitive response within gut-associated lymphoid tissue [2]. Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are more likely to involve intestinal segments with higher intestinal bacteria concentration, alterations in the composition and metabolism of gut microbiota in IBD patients have been identified by molecular techniques [2, 28]. Studies have proposed that microbial diversity in active IBD patients is decreased, with depletion of commensal bacteria including Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, and concomitant increase in Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Enterobacteriaceae [2, 8]. Decrease in SCFA production by primarily Clostridia and Bacteroides that are depleted in IBD patients, and overproduction of hydrogen sulfide by overgrowing sulfate-reducing bacteria in ulcerative colitis patients can result in epithelial nutrition deficiency [8, 29, 30]. Recently, more and more evidence suggested that SCFA, particularly acetate, butyrate, and propionate, which were metabolized by gut bacteria from fiber-rich diet, has regulatory effect on intestinal immune response and anti-inflammatory effect thus alleviating autoimmune related diseases including IBD in animal models. Recently, butyrate, a bioactive SCFA, has also been shown to play a controversial role in tumorigenesis in the gut [31,32,33]. F. prausnitzii was identified as an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium and might be a promising strategy in Crohn’s disease [12]. Antibiotics and probiotics have also been suggested to ameliorate some types of IBD by remediation of gut microbiota [34].

Obesity with its increasing prevalence and comorbidity worldwide has become a focus point of gut microbiome research during more recent years. Obesity has been shown to be associated with a significant decrease in the level of microbiota diversity, decreased proportion of Bacteroidetes, and increased proportion of Actinobacteria; while the proportion of Bacteroidetes increases with weight loss despite total caloric intake [14, 35]. Obesity-associated gut microbiota has been found to have an increased capacity for energy harvest; this was validated in animal studies by transplantation of lean and obese caecal microbiotas into germ-free mouse recipients [3]. These research findings also proposed that human obesity could be managed by manipulating gut microbiota, although further studies in human subjects are needed.

Akkermansia muciniphila, an abundant constituent of the human microbiota that resides in the mucus layer of the gut, is one of the promising targets in future generation probiotic research as it may play a role in the management of obesity and metabolic syndrome, inflammations, autoimmune diseases, and cancer. A. muciniphila is proposed to promote gut homeostasis and human health by inducing mucus production, innate immune signaling via Toll-like receptor [6], and expression of antibacterial peptide; causing microbiota remodeling; lower serum endotoxin; etc. [36, 37]. Studies suggested that A. muciniphila abundance is inversely correlated with obesity, metabolic syndrome, IBD, and acute appendicitis [38,39,40,41]. Recent study also suggests an association between A. muciniphila abundance and clinical response to PD-1-based immune check-point inhibitors [42]. Supplementation of A. muciniphila to mice gut has been shown to be protective against development of obesity, type 1 and type 2 diabetes, atherosclerosis, and poor response to the antitumor effects of PD-1 blockade [36, 38, 42,43,44]. Ongoing research is further investigating A. muciniphila as a therapeutic tool in the management of multiple diseases.

Intestinal microbiota-host interaction has been shown to play a role not only in gastrointestinal diseases, but also in extra-gastrointestinal diseases [45, 46]. Studies have shown correlation between intestinal microbiome and extra-gastrointestinal malignancy and its response to immunotherapy [47, 48], atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Wang et al. and Tang et al. [49, 50] psychiatric diseases including mood disorders, schizophrenia, and autism spectrum disorder [51,52,53,54,55], neurologic diseases including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis [56,57,58], metabolic disorders including diabetes [59, 60], allergic/immunologic diseases including asthma, systemic lupus erythematosus, autoimmune arthritis, and inflammatory skin diseases [58, 61,62,63]. Targeting the gut microbiome dysbiosis to intervene in the underlying pathogenesis might be the new therapeutic approach for diseases of multiple systems.

Compared to traditional reviews, analysis based on Citespace provides a better insight of the evolving research foci and trends, but it comes with certain limitations. Similar words need be merged together during the analysis; even though only original articles were included in the majority of analysis, all article types were included during the co-cited reference analysis.

Conclusions

There is no doubt that our understanding of gut microbiome has significantly advanced via bursts of high quality research occurring over the past 20 years. With the help of information visualization, we were able to identify research foci and overall trends in the field and offer gathered information to future researchers. We believe gut microbiota is associated with the pathogenesis of significantly more diseases than we currently know of. The emerging new therapeutic targets in gut microbiota would be the foci of future research.

Abbreviations

- 16S rRNA:

-

16S ribosomal RNA

- IBD:

-

inflammatory bowel disease

- WoScc:

-

Web of Science Core Collection

- SCFA:

-

short-chain fatty acid

References

Sokol H, Seksik P, Furet JP, Firmesse O, Nion-Larmurier I, Beaugerie L, Cosnes J, Corthier G, Marteau P, Dore J. Low counts of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in colitis microbiota. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(8):1183–9.

Frank DN, St Amand AL, Feldman RA, Boedeker EC, Harpaz N, Pace NR. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(34):13780–5.

Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444(7122):1027–31.

Xiao L, Feng Q, Liang S, Sonne SB, Xia Z, Qiu X, Li X, Long H, Zhang J, Zhang D, et al. A catalog of the mouse gut metagenome. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(10):1103–8.

Xu J, Bjursell MK, Himrod J, Deng S, Carmichael LK, Chiang HC, Hooper LV, Gordon JI. A genomic view of the human-Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron symbiosis. Science (New York, NY). 2003;299(5615):2074–6.

Ley RE, Peterson DA, Gordon JI. Ecological and evolutionary forces shaping microbial diversity in the human intestine. Cell. 2006;124(4):837–48.

Backhed F, Ley RE, Sonnenburg JL, Peterson DA, Gordon JI. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science. 2005;307(5717):1915–20.

Sartor RB. Microbial influences in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(2):577–94.

Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118(2):229–41.

Stappenbeck TS, Hooper LV, Gordon JI. Developmental regulation of intestinal angiogenesis by indigenous microbes via Paneth cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(24):15451–5.

Clavel T, Haller D. Bacteria- and host-derived mechanisms to control intestinal epithelial cell homeostasis: implications for chronic inflammation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13(9):1153–64.

Sokol H, Pigneur B, Watterlot L, Lakhdari O, Bermudez-Humaran LG, Gratadoux JJ, Blugeon S, Bridonneau C, Furet JP, Corthier G, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(43):16731–6.

Eckburg PB, Bik EM, Bernstein CN, Purdom E, Dethlefsen L, Sargent M, Gill SR, Nelson KE, Relman DA. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science (New York, NY). 2005;308(5728):1635–8.

Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE, Sogin ML, Jones WJ, Roe BA, Affourtit JP, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457(7228):480–4.

Sartor RB. Mechanisms of disease: pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;3(7):390–407.

Chen C, Hu Z, Liu S, Tseng H. Emerging trends in regenerative medicine: a scientometric analysis in CiteSpace. Exp Opin Biol Ther. 2012;12(5):593–608.

Guslandi M, Mezzi G, Sorghi M, Testoni PA. Saccharomyces boulardii in maintenance treatment of Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45(7):1462–4.

Canani RB, Costanzo MD, Leone L, Pedata M, Meli R, Calignano A. Potential beneficial effects of butyrate in intestinal and extraintestinal diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(12):1519–28.

Manichanh C, Rigottier-Gois L, Bonnaud E, Gloux K, Pelletier E, Frangeul L, Nalin R, Jarrin C, Chardon P, Marteau P, et al. Reduced diversity of faecal microbiota in Crohn’s disease revealed by a metagenomic approach. Gut. 2006;55(2):205–11.

Harmsen HJ, Wildeboer-Veloo AC, Raangs GC, Wagendorp AA, Klijn N, Bindels JG, Welling GW. Analysis of intestinal flora development in breast-fed and formula-fed infants by using molecular identification and detection methods. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;30(1):61–7.

Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, Venturi A, Brigidi P, Matteuzzi D, Bazzocchi G, Poggioli G, Miglioli M, Campieri M. Oral bacteriotherapy as maintenance treatment in patients with chronic pouchitis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(2):305–9.

Khoruts A, Dicksved J, Jansson JK, Sadowsky MJ. Changes in the composition of the human fecal microbiome after bacteriotherapy for recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44(5):354–60.

Brun P, Castagliuolo I, Di Leo V, Buda A, Pinzani M, Palu G, Martines D. Increased intestinal permeability in obese mice: new evidence in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292(2):G518–25.

Kruis W, Schutz E, Fric P, Fixa B, Judmaier G, Stolte M. Double-blind comparison of an oral Escherichia coli preparation and mesalazine in maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11(5):853–8.

Rao AV, Bested AC, Beaulne TM, Katzman MA, Iorio C, Berardi JM, Logan AC. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of a probiotic in emotional symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome. Gut Pathog. 2009;1(1):6.

Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, Nielsen T, Pons N, Levenez F, Yamada T, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464(7285):59–65.

Arumugam M, Raes J, Pelletier E, Le Paslier D, Yamada T, Mende DR, Fernandes GR, Tap J, Bruls T, Batto JM, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2011;473(7346):174–80.

Eckburg PB, Relman DA. The role of microbes in Crohn’s disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(2):256–62.

Smith FM, Coffey JC, Kell MR, O’Sullivan M, Redmond HP, Kirwan WO. A characterization of anaerobic colonization and associated mucosal adaptations in the undiseased ileal pouch. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7(6):563–70.

Roediger WE, Duncan A, Kapaniris O, Millard S. Reducing sulfur compounds of the colon impair colonocyte nutrition: implications for ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1993;104(3):802–9.

Sun M, Wu W, Liu Z, Cong Y. Microbiota metabolite short chain fatty acids, GPCR, and inflammatory bowel diseases. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(1):1–8.

Singh N, Gurav A, Sivaprakasam S, Brady E, Padia R, Shi H, Thangaraju M, Prasad PD, Manicassamy S, Munn DH, et al. Activation of Gpr109a, receptor for niacin and the commensal metabolite butyrate, suppresses colonic inflammation and carcinogenesis. Immunity. 2014;40(1):128–39.

Belcheva A, Irrazabal T, Robertson SJ, Streutker C, Maughan H, Rubino S, Moriyama EH, Copeland JK, Surendra A, Kumar S, et al. Gut microbial metabolism drives transformation of MSH2-deficient colon epithelial cells. Cell. 2014;158(2):288–99.

Sartor RB. Therapeutic manipulation of the enteric microflora in inflammatory bowel diseases: antibiotics, probiotics, and prebiotics. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(6):1620–33.

Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 2006;444(7122):1022–3.

Hanninen A, Toivonen R, Poysti S, Belzer C, Plovier H, Ouwerkerk JP, Emani R, Cani PD, De Vos WM. Akkermansia muciniphila induces gut microbiota remodelling and controls islet autoimmunity in NOD mice. Gut. 2018;67(8):1445–53.

Plovier H, Everard A, Druart C, Depommier C, Van Hul M, Geurts L, Chilloux J, Ottman N, Duparc T, Lichtenstein L, et al. A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila or the pasteurized bacterium improves metabolism in obese and diabetic mice. Nat Med. 2017;23(1):107–13.

Everard A, Belzer C, Geurts L, Ouwerkerk JP, Druart C, Bindels LB, Guiot Y, Derrien M, Muccioli GG, Delzenne NM, et al. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(22):9066–71.

Le Chatelier E, Nielsen T, Qin J, Prifti E, Hildebrand F, Falony G, Almeida M, Arumugam M, Batto JM, Kennedy S, et al. Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature. 2013;500(7464):541–6.

Png CW, Linden SK, Gilshenan KS, Zoetendal EG, McSweeney CS, Sly LI, McGuckin MA, Florin TH. Mucolytic bacteria with increased prevalence in IBD mucosa augment in vitro utilization of mucin by other bacteria. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(11):2420–8.

Swidsinski A, Dorffel Y, Loening-Baucke V, Theissig F, Ruckert JC, Ismail M, Rau WA, Gaschler D, Weizenegger M, Kuhn S, et al. Acute appendicitis is characterised by local invasion with Fusobacterium nucleatum/necrophorum. Gut. 2011;60(1):34–40.

Routy B, Le Chatelier E, Derosa L, Duong CPM, Alou MT, Daillere R, Fluckiger A, Messaoudene M, Rauber C, Roberti MP, et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science (New York, NY). 2018;359(6371):91–7.

Shin NR, Lee JC, Lee HY, Kim MS, Whon TW, Lee MS, Bae JW. An increase in the Akkermansia spp. population induced by metformin treatment improves glucose homeostasis in diet-induced obese mice. Gut. 2014;63(5):727–35.

Li J, Lin S, Vanhoutte PM, Woo CW, Xu A. Akkermansia muciniphila protects against atherosclerosis by preventing metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in Apoe−/− Mice. Circulation. 2016;133(24):2434–46.

Singh RK, Chang HW, Yan D, Lee KM, Ucmak D, Wong K, Abrouk M, Farahnik B, Nakamura M, Zhu TH, et al. Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. J Transl Med. 2017;15(1):73.

Lynch SV, Pedersen O. The human intestinal microbiome in health and disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(24):2369–79.

Gopalakrishnan V, Spencer CN, Nezi L, Reuben A, Andrews MC, Karpinets TV, Prieto PA, Vicente D, Hoffman K, Wei SC, et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science. 2018;359(6371):97–103.

Yang J, Tan Q, Fu Q, Zhou Y, Hu Y, Tang S, Zhou Y, Zhang J, Qiu J, Lv Q. Gastrointestinal microbiome and breast cancer: correlations, mechanisms and potential clinical implications. Breast Cancer (Tokyo, Japan). 2017;24(2):220–8.

Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ, Koeth R, Levison BS, Dugar B, Feldstein AE, Britt EB, Fu X, Chung YM, et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2011;472(7341):57–63.

Tang WH, Wang Z, Levison BS, Koeth RA, Britt EB, Fu X, Wu Y, Hazen SL. Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(17):1575–84.

Sharon G, Sampson TR, Geschwind DH, Mazmanian SK. The Central Nervous System and the Gut Microbiome. Cell. 2016;167(4):915–32.

Mangiola F, Ianiro G, Franceschi F, Fagiuoli S, Gasbarrini G, Gasbarrini A. Gut microbiota in autism and mood disorders. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(1):361–8.

Muller N, Myint AM, Schwarz MJ. Inflammation in schizophrenia. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2012;88:49–68.

Miller AH, Maletic V, Raison CL. Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol Psychiat. 2009;65(9):732–41.

Berk M, Kapczinski F, Andreazza AC, Dean OM, Giorlando F, Maes M, Yucel M, Gama CS, Dodd S, Dean B, et al. Pathways underlying neuroprogression in bipolar disorder: focus on inflammation, oxidative stress and neurotrophic factors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35(3):804–17.

Hill-Burns EM, Debelius JW, Morton JT, Wissemann WT, Lewis MR, Wallen ZD, Peddada SD, Factor SA, Molho E, Zabetian CP, et al. Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s disease medications have distinct signatures of the gut microbiome. Movement Disord. 2017;32(5):739–49.

Minter MR, Zhang C, Leone V, Ringus DL, Zhang X, Oyler-Castrillo P, Musch MW, Liao F, Ward JF, Holtzman DM, et al. Antibiotic-induced perturbations in gut microbial diversity influences neuro-inflammation and amyloidosis in a murine model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30028.

de Oliveira GLV, Leite AZ, Higuchi BS, Gonzaga MI, Mariano VS. Intestinal dysbiosis and probiotic applications in autoimmune diseases. Immunology. 2017;152(1):1–12.

Duan F, Curtis KL, March JC. Secretion of insulinotropic proteins by commensal bacteria: rewiring the gut to treat diabetes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(23):7437–8.

Duan FF, Liu JH, March JC. Engineered commensal bacteria reprogram intestinal cells into glucose-responsive insulin-secreting cells for the treatment of diabetes. Diabetes. 2015;64(5):1794–803.

McKenzie C, Tan J, Macia L, Mackay CR. The nutrition–gut microbiome-physiology axis and allergic diseases. Immunol Rev. 2017;278(1):277–95.

Horta-Baas G, Romero-Figueroa MDS, Montiel-Jarquin AJ, Pizano-Zarate ML, Garcia-Mena J, Ramirez-Duran N. Intestinal dysbiosis and rheumatoid arthritis: a link between gut microbiota and the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol Res. 2017;2017:4835189.

Song H, Yoo Y, Hwang J, Na YC, Kim HS. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii subspecies-level dysbiosis in the human gut microbiome underlying atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(3):852–60.

Authors’ contributions

Guarantor of the article: SC. SC conceived the study and performed critical revision of manuscript. XH and XF contributed equally to this work. XH designed the study, performed statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. XF designed the study and wrote the manuscript. JY performed the article retrieval, data interpretation and provided supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Evidence Based Medicine center of Fudan University and Fudan University Library for supporting the work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Foundation of Discipline Construction of Evidence-based Medicine Center, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, China, and partly supported by the 3-year Action Program of Shanghai Municipality for Strengthening the Construction of Public Health System (No. 15GWZK0901). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, X., Fan, X., Ying, J. et al. Emerging trends and research foci in gastrointestinal microbiome. J Transl Med 17, 67 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-019-1810-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-019-1810-x