Abstract

Background

To inform implementation and future research, this scoping review investigates the volume of evidence for physical activity interventions among adults aged 60+. Our research questions are: (1) what is the evidence regarding interventions designed to increase total physical activity in adults aged 60+ years, in accordance with three of the four strategic objectives of GAPPA (active societies, active environments, active people); (2) what is the current evidence regarding the effectiveness of physical activity programmes and services designed for older adults?; and (3) What are the evidence gaps requiring further research?

Methods

We searched PEDro, MEDLINE, CINAHL and Cochrane from 1 January 2010 to 1 November 2020 for systematic reviews and meta-analyses of physical activity interventions in adults aged 60+. We identified interventions designed to: (1) increase physical activity; and (2) deliver physical activity programmes and services in home, community or outpatient settings. We extracted and coded data from eligible reviews according to our proposed framework informed by TIDieR, Prevention of Falls Network Europe (PROFANE), and WHO’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). We classified the overall findings as positive, negative or inconclusive.

Results

We identified 39 reviews of interventions to increase physical activity and 342 reviews of programmes/services for older adults. Interventions were predominantly structured exercise programmes, including balance strength/resistance training, and physical recreation, such as yoga and tai chi. There were few reviews of health promotion/coaching and health professional education/referral, and none of sport, workplace, sociocultural or environmental interventions. Fewer reported outcomes of total physical activity, social participation and quality of life/well-being. We noted insufficient coverage in diverse and disadvantaged samples and low-middle income countries.

Conclusions

There is a modest but growing volume of evidence regarding interventions designed to increase total physical activity in older adults, although more interventional studies with long term follow-up are needed, particularly for GAPPA 1. Active Societies and GAPPA 2. Active Environments. By comparison, there is abundant evidence for GAPPA 3. specific programmes and services, but coverage of sport and workplace interventions, and diverse samples and settings is lacking. Comprehensive reviews of individual studies are now needed as well as research targeting neglected outcomes, populations and settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In October 2020 the World Health Organization (WHO) launched the Decade of Healthy Ageing 2021–2030 in response to rapid, global population ageing [1]. There are currently more than one billion people (12%) aged over 60 years and this is forecast to grow to 2 billion (22%) by 2050 [2]. Moreover, 80% of these older adults are projected to live in low- and middle-income countries with limited access to health services and, as shown by the current COVID-19 pandemic, age is associated with increased risk of disease, co-morbidity and loss of independence [2]. This initiative is part of the United Nations’ 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda [3] and WHO Global Strategy and Action Plan on Ageing and Health [2] (GSAP) and argues a universal right to health at all ages.

Once called the ‘Cinderella risk factor’ for non-communicable disease (NCD) prevention due to policy neglect and inadequate resourcing [4], physical activity is globally recognised as important for supporting healthy ageing in a number of ways. In the 2015 Report on Ageing and Health [5] WHO identified the potential for physical activity to slow age-related decline in functional ability, and develop and maintain physical and mental intrinsic capacity in older adults. This new conceptual approach acknowledges the functional diversity among older adults and focuses on health and capability rather than chronological age. In this way, physical activity is a key enabler of work, social contribution, autonomy and dignity as well as health in older age.

The 2020 WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour [6] call for older adults to undertake 150–300 min of moderate intensity physical activity (or 75–150 min vigorous), including muscle strengthening on at least 2 days per week and varied multicomponent physical activity emphasizing functional balance and strength training on at least 3 days per week. There is an urgent need for global action on physical inactivity as one in four adults are insufficiently active with higher rates in women and older adults [7]. Only one in two older adults regularly undertake physical activity and fewer engage in multicomponent physical activity targeting functional balance and strength as recommended in the 2020 WHO Guidelines [6]. The WHO Global Action Plan on Physical Activity (GAPPA) sets out four strategic policy objectives (Active Societies, Active Environments, Active People, and Active Systems) and 20 related policy actions, that aim to address the social, cultural, environmental and individual determinants of physical inactivity. The resolution adopting the GAPPA (World Health Assembly WHA71) also recorded member states’ request for support with implementation, and specific tools and resources for the policy actions areas.

To assist countries to adopt, tailor and implement the recommendations into their local contexts, WHO is developing ACTIVE [8], a technical toolkit with implementation guidance for key approaches, settings and population groups. WHO commissioned this scoping review of physical activity intervention literature for older adults to assess available volume of evidence to support toolkit development and inform the direction of further research.

Previous reviews of physical activity literature for older adults focus largely on falls prevention [9], acute care rehabilitation, and/or specific health conditions [10, 11]. These condition-centric approaches are useful for clinical practice but sub-optimal to inform population-wide intervention approaches. There is one recent notable exception in Di Lorito et al. [12], although this review targeted structured exercise rather than the wider definition of physical activity and/or alternate approaches to increase physical activity. There are also some scoping reviews of physical activity in older adults [13, 14], although none attempt a public health approach. Given our interest in interventions to: [1] increase total physical activity; and [2] deliver physical activity programmes and services for older adults, we have chosen a scoping review methodology to deliver a timely, initial assessment of the entire physical activity evidence base.

Objectives

We conducted a scoping review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of physical activity interventions for older adults and classified them using a two-component conceptual framework that we developed based on the GAPPA, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [15], the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) framework [16, 17] and the Prevention of Falls Network Europe (PROFANE) taxonomy [18, 19].

This scoping review of physical activity interventions for older adults addresses the following research questions:

-

1.

What is the evidence regarding interventions designed to increase total physical activity in adults aged 60+ years, and how might they be classified within three of the four strategic objectives of GAPPA:

-

a.

Active societies

-

b.

Active environments

-

c.

Active people

-

a.

-

2.

What is the current evidence regarding effectiveness for GAPPA Action 3.4 to deliver physical activity programmes and services, and:

“Enhance the provision of, and opportunities for, appropriately tailored programmes and services aimed at increasing physical activity and reducing sedentary behaviour in older adults, according to ability, in key settings such as local and community venues, health, social and long-term care settings, assisted living facilities and family environments, to support healthy ageing.”? [7]

-

3.

What are the evidence gaps requiring further research?

Research question one includes a broad range of interventions that aim to increase total/overall physical activity in older adults. These may include: physical activity promotion in mass media campaigns; health professional coaching/referral schemes; environmental programs and/or community campaigns; as well as structured exercise or physical activity programmes and devices with total physical activity outcomes. Research question two focuses on interventions that deliver exercise and physical activity programmes directly to older adults and consider the impact on a range of outcomes. These often incorporate outcomes of strength, balance, or mobility, and may/may not measure total physical activity.

Method

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [20]. A protocol was prepared in advance and published on the Open Science Framework [21].

Search strategy

We searched the following four databases: Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro), MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews from 1 January 2010 to 1 November 2020. Keywords, MeSH and other index terms, as well as combinations of these terms and appropriate synonyms, were used to construct the search strategy. Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers (JT and SW) using Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Four reviewers read full-texts and assessed eligibility criteria (JT, SW, JSO, MP). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus or referred to senior investigators (CS and AT). A sample search strategy is included at Table 1.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were selected for research questions one and/or research question two according to eligibility criteria described in Table 2. In general, studies were eligible if they reported on interventions that aimed to increase overall physical activity and addressed any of the first three GAPPA objectives: Active Societies; Active Environments; and Active People. GAPPA objective four, Active Systems, was excluded during study design given this applies predominantly to organising policy and legislative frameworks not customarily returned by the search terms and databases in scope.

We only included systematic reviews and meta-analyses of interventional studies. Individual studies and comparators did not form part of review selection criteria, although systematic reviews of individual studies may have included controlled and uncontrolled trials. Systematic reviews of cross-sectional and other observational studies were excluded, as were reviews of short-term/acute, and major, multicomponent interventions. Reviews were also excluded if they targeted specific medical conditions or diagnoses. Review quality was not assessed in this scoping review.

Data extraction, synthesis, and charting

Four independent reviewers (JT, SW, WK, LH) extracted the data using a standardised electronic data extraction form. The following data were extracted from each review: author; publication year; country; number of eligible trials; total participants; average age; and overall findings effect indicator (positive, negative or inconclusive) [22]. Our approach to effect indicator coding was generous in that we recorded a positive result where authors reported at least one outcome in our domains of interest in favour of the review intervention(s). A positive result for the purpose of this scoping review does not necessarily mean statistical significance in meta-analysis or at the level of each individual study.

Reviews were then coded according to the GAPPA objectives for research question one and a proposed two-tier classification framework for research question two. These were based on: population; intervention (informed by the TIDieR framework and PROFANE taxonomy); comparator; and outcome (PICO, informed by the ICF). Reviews eligible for research question two were coded according to framework classification level 2 (Table 3). We first coded the reviews with all (100%) of studies in a particular category (Table 3, column 4). However, given the large proportion of reviews with ‘mixed’ category results, we also coded reviews that included any (1+) studies in that category (Table 3, column 5).

Data coding, aggregation and charting was performed in Microsoft Excel using extracted data and framework coding.

Results

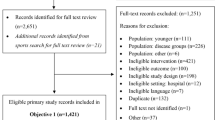

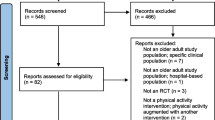

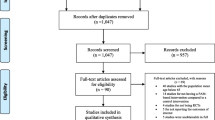

Our searches returned 4516 records. After deduplication, two reviewers screened 3401 articles by title and abstract, then full text of 1135 articles, leaving a final 39 reviews eligible for research question one and 342 reviews for research question two. We documented the screening process in a PRISMA-ScR study flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Reviews eligible for research question one focused on interventions to increase total/overall physical activity in older adults. We identified 39 such reviews, 30 with overall positive and nine with inconclusive findings. Between 2012 and 2017, three reviews were published per year on average, increasing to eight reviews per year on average between 2019 and 2020. The most common types of interventions were health promotion, eHealth, and activity trackers. As seen in Fig. 2, the number of studies in each review ranged between 3 and 113 studies (M = 10) based on database searches between 1980 and 2019. Of those with positive findings (i.e. increased total physical activity post-intervention), the number of studies ranged between 3 and 101 studies (M = 13). The number of participants ranged between 84 [23] and 19,862 [24] with a median age of 67 years. The number of studies and/or participants were not further aggregated in this analysis because studies may appear in more than one review.

Research question one – chart of reviews by number of studies reviewed and total participants. Note: Given all reviews for research question one were plotted (k = 39), the X-axis was removed as it represents sequential numbering only. The Y axis represents the number of studies in each review and bubble size indicates the total number of participants (where available). Total n was not calculated as studies may be in multiple reviews [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60]

All reviews were classified as GAPPA Objective 3. Active People (39 reviews) with no reviews addressing 1. Active Societies or 2. Active Environments. The majority (30/39, 77%) of the reviews in 3. Active People reported positive findings, in favour of intervention(s), for programmes resulting in increased overall physical activity in older adults while the remaining nine (9/39, 23%) were inconclusive.

Included reviews were generally authored in high-income countries: the UK (9/39, 23%), Australia (7/39, 18%), the United States (5/39, 13%), China (2/39, 5%), other European countries (9/39, 23%) and Canada (1/39, 2.5%). There were also reviews (one each) from Brazil, Colombia, Iran, Malaysia, and Turkey (2/39, 5%).

Reviews eligible for research question two focused on specific programmes and services of physical activity delivered directly to older adults. We identified 342 reviews that included outcomes of interest other than total/overall physical activity, such as physical functioning. Between 2010 and 2012, 14 of these reviews were published per year on average, increasing to 55 per year on average 2019–2020.

Reviews included studies from high- and upper-middle income countries almost exclusively. We found no reviews with studies from discernibly low-income countries. Samples were mostly community-dwelling older adults with some studies in residential care (Table 3), particularly of falls. There was little coverage of vulnerable populations, such as the ‘oldest’ old, rural/regional or migrant/indigenous backgrounds. While we actively excluded reviews with health conditions as eligibility criteria, more than half the reviews included studies that reported on mixed samples with some health conditions/risk factors.

The majority of reviews (290/342, 85%) reported at least one positive finding, in favour of intervention(s), in at least one of the five outcome domains of interest. Although, positive effects were most commonly reported for physical and cognitive/emotional functioning outcomes. Most reviews were of programmes that were delivered physical activity directly to participants, some with education/promotion/coaching components, and measuring physical functioning outcomes (Table 3 and Fig. 3). Fewer reviews evaluated the effect of physical activity promotion alone with overall physical activity as an outcome. Some reviews evaluated intervention(s) effects on quality of life/wellbeing but very few assessed outcomes of social participation or functioning.

Systematic reviews of physical activity programmes for older adults with positive findings by outcome domain and programme type. Note: ‘PA promoted’ refers to interventions such as health education, coaching and physical activity referral designed to increase total levels of physical activity. These interventions are often measured by physical activity outcomes such as minutes/week of moderate-vigorous physical activity, total metabolic output and/or total steps. ‘PA delivered’ refers to interventions, such as structured exercise like strength, balance, functional and/or resistance training, where the activity is provided directly to the participant. Therefore, this figure summarises the reviews reporting a positive finding in this outcome domain. Positive findings in more than one outcome domain are possible. The data labels indicate the number of reviews reporting a positive finding in that outcome category

The majority of physical activity programmes were structured exercise such as strength, balance, functional and resistance training, or physical recreation such as yoga, tai chi and walking, or mixed activities. Very few reviews considered sporting interventions for older adults and none used sport as a primary eligibility criterion. Most interventions were delivered by health and/or exercise professionals. Almost no reviews reported on programmes delivered by volunteers or carers, although a few assessed programmes for carers with outcomes of emotional functioning. The majority of reviews (259/342, 76%) included studies delivered in multiple locations (mixed) with most of these carried out in community facilities or health services, and many incorporating a home-based component.

Relevant to research question three, there were clear gaps in the evidence regarding reviews of intervention(s) with large-scale population-based study designs, particularly in mass media, social media, and environmental intervention(s). While there was some coverage of participants in residential care, included reviews overwhelmingly targeted community-dwelling older adults living in their own home. Similarly, there were very few reviews of physical activity interventions for older people living in rural or regional settings or with cultural or financial disadvantage, such as migrant or indigenous populations. Very few reviews considered health economic or large-scale implementation criteria.

While gender breakdown was not calculated at the level of individual studies in this scoping review, there was only one review explicitly targeting one gender, females. Samples were still predominantly female but most reviews did not exclude based on gender. There was a mix of individual and group-based interventions but only a few reviews that considered the benefits in terms of social participation of group-based interventions. This was also reflected in the lack of reviews on physical activity interventions in faith-based settings, sporting interventions and explicitly outdoor or park-based settings. There was also no clear focus on the tailoring/adaptation of existing community-based physical activity to include older adults with other age groups.

Devices were used, although mostly by professionals in the measurement of outcomes in the main intervention(s) rather than intended for long-term, mass engagement by participants. The only exception to this was the use of exergames which featured in the eligibility criteria of several reviews with positive effects on physical functioning outcomes. There was a gap in the clear definition of comparators, many were passive such as education, and most were mixed active/passive at the review level making comparisons of format (individual/group) and efficacy difficult.

Discussion

This scoping review found modest evidence over a 10-year period for research question one with 39 reviews of intervention(s) designed to enhance total physical activity in older adults. The majority (30/39, 77%) of these reported positive overall findings, others were inconclusive. All reviews included for research question one were categorized as meeting GAPPA Objective 3. Active People and most assessed physical activity programmes [32, 38, 44, 55] for older adults with some attention to health promotion/coaching [37, 52] and health professional education/referral [30, 56]. This demonstrates a lack of large-scale, population health-based study designs with long term follow-up and physical activity outcomes for older adults. It also reflects a broad cultural bias when considering physical activity and older people. At the time of writing, even WHO’s own Global Health Observatory (GHO) data repository does not report the prevalence indicator of insufficient physical activity separately for older adults compared to all adults aged 18 + [61]. This reflects a much-needed paradigm shift for public attitudes on health, ageing and physical activity.

We found an important gap in the evidence regarding research question one, reviews aimed at increasing total physical activity in older adults, for GAPPA 1. Active Societies (mass media, social media and other campaigns) and 2. Active Environments (interventions changing the environment) objectives. While it is possible that our search terms and scoping review methodology did not address these objectives as exhaustively as they did for GAPPA 3. Active People, it is more likely that the reviews are lacking because there are insufficient individual intervention studies. This is consistent with other research concluding that physical activity is ‘good for older adults’ but that programme implementation is being overlooked [62]. It suggests a bias towards short-term interventional studies in controlled settings with selected samples, and away from population-based and large-scale physical activity research. Similarly, for GAPPA 4. Active Systems, there were many eHealth, digital and activity trackers reviews [29, 31, 34, 45, 47, 50, 51, 57, 59, 60, 63] but none exploring monitoring at population or systemic levels. Further investigation is now required to identify individual studies, including unpublished data, in these areas.

In research question two, most (290/342, 85%) reviews of physical activity programmes and services reported at least one positive finding in an outcome domain of interest, most commonly physical activity [23, 26, 42], physical [64,65,66] and cognitive/emotional functioning [67,68,69,70], supporting the effectiveness of these interventions for older adults. However, there is far less research targeting outcomes of social functioning [71, 72] and well-being/quality of life [73,74,75]. This will require a necessary shift to a population-based approach in physical activity research for older adults.

Consistent with recent literature [12], most of the reviews we identified relate to interventions of structured exercise [76, 77], including strength, balance, and resistance training, and physical recreation [78,79,80] including yoga and tai chi. A number of structured exercise interventions included video or exergames [81,82,83] but no reviews targeted sport-based programmes for older adults and this should be investigated further. Many reviews also failed to be selective for intervention type, mixing structured exercise and physical recreation, making recommendations about efficacy/acceptability difficult.

In line with our inpatient exclusion criterion, most eligible reviews targeted community-dwelling older adults [9, 84], although there was some coverage of residential care settings [41, 85], particularly in the falls prevention literature. Despite many older people maintaining employment, there were no reviews exclusively targeting the workplace and only two including a workplace setting [25, 86] and one of physical activity in ‘retirement transition’ [26].

Importantly, few of the reviews in either research question appeared to consider the diversity of function and intrinsic capacity in older adults. There were very few reviews focused on the ‘oldest old’ [87], and samples from geographically [49] or socioeconomically [43, 48, 88] disadvantaged populations and none targeted low-income countries. This is likely due to the lack of underlying longitudinal studies of these samples but also reveals inherent difficulties in the recruitment and retention of older adults [89, 90]. Moreover, many older adults are living with chronic/comorbid conditions and preconditions that confound studies of ‘healthy’ samples. Although we excluded reviews of specific medical conditions, review selection criteria of ‘healthy older adults’ was common [67, 74, 80], despite the high prevalence of chronic comorbidity.

Strengths and limitations

The comprehensive search strategy, the GAPPA, and two-tier coding framework based on TIDieR, PROFANE, and the ICF were major strengths of this review. This review analysed a large and encouraging volume of research of physical activity interventions for older people and identified important gaps in the literature.

A scoping review methodology, such as that adopted in this study, is limited in its capacity to make recommendations about the efficacy of individual interventions. Reviews investigating the effects of physical activity interventions combined with other interventions were excluded. This may have resulted in the omission of important/relevant evidence regarding multicomponent or ‘real-world’ interventions. Commensurate with a scoping methodology, the scale of this review did not permit quality assessment at the level of individual studies. As this analysis remained at the review level, not the level of individual studies, it is also possible that studies were counted more than once across multiple reviews. These should be addressed in a subsequent review of individual studies.

Conclusion

This scoping review identified a modest volume of evidence regarding interventions designed to increase total physical activity in older people (research question one), although more population-based and long-term follow-up intervention studies are needed, particularly in health promotion, coaching and health professional education/referral between healthcare and community settings. Research gaps were identified in social (mass-media), environmental, and systemic areas for the GAPPA objectives other than 3. Active People.

This review also found a large amount of evidence regarding specific physical activity programmes and services (research question two). In particular, there was a substantial volume of evidence demonstrating benefits of structured exercise and to a lesser extent physical recreation, particularly on outcomes of mobility, strength and balance. However, we found gaps in studies of sporting and workplace physical activity interventions targeting older people. There was also a notable lack of research in diverse/disadvantaged samples and social participation outcomes. The next steps are to assess each of the individual studies covered in these reviews and initiate research to address the gaps in evidence. These represent opportunities for an evidence base that more closely reflects the diversity of ageing with widespread acceptance of the right to the health and social benefits of physical activity at every age.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during this review are available from the authors on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- CONSORT:

-

Consolidated Standard of Reporting Trials

- GAPPA:

-

Global Action Plan on Physical Activity (WHO) [7]

- GSAP:

-

Global Strategy and Action Plan on Ageing and Health (WHO) [2]

- ICF:

-

International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health [15]

- NCD:

-

Noncommunicable diseases

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- PEDro:

-

Physiotherapy Evidence Database (www.pedro.org.au)

- PICO:

-

Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome

- PRISMA-ScR:

-

PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews [20]

- PROFANE:

-

Prevention of Falls Network Europe

- TIDieR:

-

Template for Intervention Description and Replication (CONSORT)

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

WHO. Decade of Healthy Ageing 2020–2030; 2020, https://www.who.int/ageing/decade-of-healthy-ageing (Accessed 18 Nov 2020).

WHO. Global strategy and action plan on ageing and health. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 2017.

UN. The Sustainable Development Agenda, 2017. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda/ (Accessed 11 Jan 2021).

Bull FC, Bauman AE. Physical inactivity: the “Cinderella” risk factor for noncommunicable disease prevention. J Health Commun. 2011;16(Suppl 2):13–26. 2011/09/23. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2011.601226.

WHO. World report on ageing and health. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 2015. Report no. 978 92 4 156504 2

WHO. WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 2020.

WHO. Global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030: more active people for a healthier world. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 2018.

WHO. Active: A technical package for increasing physical activity, 2018. https://www.who.int/ncds/prevention/physical-activity/active-toolkit/en/ (Accessed 13 Dec 2020).

Sherrington C, Fairhall NJ, Wallbank GK, et al. Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1:Cd012424. 2019/02/01. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012424.pub2.

Brasure M, Desai P, Davila H, et al. Physical activity interventions in preventing cognitive decline and Alzheimer-type Dementia: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168:30–8. 2017/12/20. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-1528.

Cusso ME, Donald KJ, Khoo TK. The impact of physical activity on non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. Front Med. 2016;3:35. 2016/09/02. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2016.00035.

Di Lorito C, Long A, Byrne A, et al. Exercise interventions for older adults: A systematic review of meta-analyses. J Sport Health Sci. 2020. 2020/06/12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2020.06.003.

Hu YL, Junge K, Nguyen A, et al. Evidence to improve physical activity among medically underserved older adults: a scoping review. Gerontologist. 2019;59:e279–93. 2018/04/19. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny030.

Ley L, Khaw D, Duke M, et al. The dose of physical activity to minimise functional decline in older general medical patients receiving 24-hr acute care: A systematic scoping review. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28:3049–64. 2019/04/03. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14872.

WHO. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 2018.

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687. 2014/03/13. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1687.

EQUATOR. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide, https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/tidier/ (2020).

Lamb SE, Jorstad-Stein EC, Hauer K, et al. Development of a common outcome data set for fall injury prevention trials: the Prevention of Falls Network Europe consensus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1618–22. 2005/09/03. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53455.x.

PROFANE. Manual for the fall prevention classification system. Manchester: The University of Manchester: Prevention of Falls Network Europe (ProFaNE); 2007.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73. 2018/09/05. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

Taylor J, Walsh S, Kwok W, et al. Scoping review of physical activity interventions for older adults: protocol, 2020. https://osf.io/p27j8/ (Accessed 14 Jan 2021).

Bushman B, Wang MC. Vote-counting procedures in meta-analysis. In: Cooper HM, Hedges LV, Valentine JC, editors. The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis. 2nd ed. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2009. p. 207–20.

Akinrolie O, Barclay R, Strachan S, Gupta A, Jasper US, Jumbo SU, et al. The effect of motivational interviewing on physical activity level among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. 2020;38:250–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703181.2020.1725217.

Beishuizen CR, Stephan BC, van Gool WA, et al. Web-based interventions targeting cardiovascular risk factors in middle-aged and older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:e55. 2016/03/13. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5218.

Arbesman M, Mosley LJ. Systematic review of occupation- and activity-based health management and maintenance interventions for community-dwelling older adults. Am J Occup Ther. 2012;66:277–83. 2012/05/03. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2012.003327.

Baxter S, Johnson M, Payne N, et al. Promoting and maintaining physical activity in the transition to retirement: a systematic review of interventions for adults around retirement age. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:12. 2016/02/03. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0336-3.

Burton E, Lewin G, Boldy D. A systematic review of physical activity programs for older people receiving home care services. J Aging Phys Act. 2015;23:460–70. 2014/10/25. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.2014-0086.

Burton E, Farrier K, Hill KD, et al. Effectiveness of peers in delivering programs or motivating older people to increase their participation in physical activity: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sports Sci. 2018;36:666–78. 2017/05/24. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2017.1329549.

Buyl R, Beogo I, Fobelets M, et al. e-Health interventions for healthy aging: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2020;9:128. 2020/06/05. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01385-8.

Campbell F, Holmes M, Everson-Hock E, et al. A systematic review and economic evaluation of exercise referral schemes in primary care: a short report. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19:1–110. 2015/07/30. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta19600.

Changizi M, Kaveh MH. Effectiveness of the mHealth technology in improvement of healthy behaviors in an elderly population-a systematic review. mHealth. 2017;3:51. 2018/02/13. https://doi.org/10.21037/mhealth.2017.08.06.

Chase JA. Interventions to increase physical activity among older adults: a meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2015;55:706–18. 2014/10/10. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu090.

Clark IN, Taylor NF, Baker F. Music interventions and physical activity in older adults: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Rehabil Med. 2012;44:710–9. 2012/08/03. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-1025.

Cooper C, Gross A, Brinkman C, et al. The impact of wearable motion sensing technology on physical activity in older adults. Exp Gerontol. 2018;112:9–19. 2018/08/14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2018.08.002.

French DP, Olander EK, Chisholm A, et al. Which behaviour change techniques are most effective at increasing older adults’ self-efficacy and physical activity behaviour? A systematic review. Ann Behav Med. 2014;48:225–34. 2014/03/22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-014-9593-z.

Geraedts H, Zijlstra A, Bulstra SK, et al. Effects of remote feedback in home-based physical activity interventions for older adults: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;91:14–24. 2012/12/01. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.10.018.

Goethals L, Barth N, Hupin D, Mulvey MS, Roche F, Gallopel-Morvan K, et al. Social marketing interventions to promote physical activity among 60 years and older: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Public Health. 2020;20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09386-x.

Grande GD, Oliveira CB, Morelhao PK, et al. Interventions promoting physical activity among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2019. 2019/12/24. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz167.

Hobbs N. Are behavioral interventions effective in increasing physical activity at 12 to 36 months in adults aged 55 to 70 years? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2013;11:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-75.

Ilgaz A, Gozum S. Health promotion interventions for older people living alone: a systematic review. Perspect Public Health. 2019;139:255–63. 2019/02/14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913918803980.

Jansen CP, Classen K, Wahl HW, et al. Effects of interventions on physical activity in nursing home residents. Eur J Ageing. 2015;12:261–71. 2015/05/08. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-015-0344-1.

Kassavou A, Turner A, French DP. Do interventions to promote walking in groups increase physical activity? A meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10(1):18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-18.

Katigbak C, Flaherty E, Chao YY, et al. A systematic review of culturally specific interventions to increase physical activity for older asian americans. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018;33:313–21. 2018/02/21. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCN.0000000000000459.

Kidd T, Mold F, Jones C, et al. What are the most effective interventions to improve physical performance in pre-frail and frail adults? A systematic review of randomised control trials. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:184. 2019/07/12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1196-x.

Kwan RYC, Salihu D, Lee PH, et al. The effect of e-health interventions promoting physical activity in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act. 2020;17:7. 2020/04/28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11556-020-00239-5.

Larsen RT, Christensen J, Juhl CB, et al. Physical activity monitors to enhance amount of physical activity in older adults - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act. 2019;16:7. 2019/05/11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11556-019-0213-6.

Liu JY, Kor PP, Chan CP, et al. The effectiveness of a wearable activity tracker (WAT)-based intervention to improve physical activity levels in sedentary older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;91:104211. 2020/08/03. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2020.104211.

Montayre J, Neville S, Dunn I, et al. What makes community-based physical activity programs for culturally and linguistically diverse older adults effective? A systematic review. Aust J Ageing 2020. 2020/07/01. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12815, 39, 4, 331, 340.

Moore M, Warburton J, O'Halloran PD, et al. Effective community-based physical activity interventions for older adults living in rural and regional areas: a systematic review. J Aging Phys Act. 2016;24:158–67. 2015/05/30. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.2014-0218.

Mueller A, Khoo S. Non-face-to-face physical activity interventions in older adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11:1–2.

Muellmann S, Forberger S, Mollers T, et al. Effectiveness of eHealth interventions for the promotion of physical activity in older adults: A systematic review. Prev Med. 2018;108:93–110. 2018/01/01. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.12.026.

Neidrick TJ, Fick DM, Loeb SJ. Physical activity promotion in primary care targeting the older adult. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2012;24:405–16. 2012/06/28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7599.2012.00703.x.

Oliveira JS, Sherrington C, Amorim AB, et al. What is the effect of health coaching on physical activity participation in people aged 60 years and over? A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51:1425–32. 2017/03/23. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096943.

Oliveira J, Sherrington C, et al. Effect of interventions using physical activity trackers on physical activity in people aged 60 years and over: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2019 2019/08/11. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-100324.

Sansano-Nadal O, Gine-Garriga M, Brach JS, et al. Exercise-based interventions to enhance long-term sustainability of physical activity in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16 2019/07/18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142527.

Stevens Z, Barlow C, Kendrick D, et al. Effectiveness of general practice-based physical activity promotion for older adults: systematic review. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2014;15:190–201. 2013/03/20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423613000017.

Taraldsen K, Chastin SF, et al. Physical activity monitoring by use of accelerometer-based body-worn sensors in older adults: a systematic literature review of current knowledge and applications. Maturitas. 2012;71:13–9. 2011/12/03. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.11.003.

Thiebaud RS, Funk MD, Abe T. Home-based resistance training for older adults: a systematic review. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014;14:750–7. 2014/08/12. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12326.

Tonga E, Srikesavan C, Williamson E, et al. Components, design and effectiveness of digital physical rehabilitation interventions for older people: A systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2020. 2020/06/11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X20927587.

Yerrakalva D, Yerrakalva D, Hajna S, et al. Effects of mobile health app interventions on sedentary time, physical activity, and fitness in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21:e14343. 2019/11/30. https://doi.org/10.2196/14343.

WHO. The global health observatory. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 2020.

Gray SM, McKay HA, Nettlefold L, et al. Physical activity is good for older adults-but is programme implementation being overlooked? A systematic review of intervention studies that reported frameworks or measures of implementation. Br J Sports Med. 2020 2020/10/09. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102465.

Stockwell S, Schofield P, Fisher A, et al. Digital behavior change interventions to promote physical activity and/or reduce sedentary behavior in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp Gerontol. 2019;120:68–87. 2019/03/06. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2019.02.020.

Nash KCM. The effects of exercise on strength and physical performance in frail older people: a systematic review. Rev Clin Gerontol. 2012;22:274–85. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0959259812000111.

Chase JD, Phillips LJ, Brown M. Physical activity intervention effects on physical function among community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Aging Phys Act. 2017;25:149–70. 2016/09/14. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.2016-0040.

Lewis FJ, Stewart HC, Roddam H. Effects of exercise interventions on physical function, mobility, frailty status and strength in the pre-frail population: a review of the evidence base for practice. Eur J Phys. 2019:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/21679169.2019.1645882.

Chang Y-K, Pan C-Y, Chen F-T, Tsai CL, Huang CC. Effect of resistance-exercise training on cognitive function in healthy older adults: a review. J Aging Phys Act. 2012;20:497–517. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.20.4.497.

Miller SM, Taylor-Piliae RE. Effects of Tai Chi on cognitive function in community-dwelling older adults: a review. Geriatr Nurs. 2014;35:9–19. 2013/11/21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2013.10.013.

Falck RS, Davis JC, Best JR, et al. Impact of exercise training on physical and cognitive function among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;79:119–30. 2019/05/06. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.03.007.

Klil-Drori S, Klil-Drori AJ, Pira S, et al. Exercise intervention for late-life depression: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81 2020/01/23. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.19r12877.

Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Du S, et al. Exercise interventions for improving physical function, daily living activities and quality of life in community-dwelling frail older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Geriatr Nurs. 2020;41:261–73. 2019/11/11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2019.10.006.

Roberts CE, Phillips LH, Cooper CL, et al. Effect of different types of physical activity on activities of daily living in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Aging Phys Act. 2017;25:653–70. 2017/02/10. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.2016-0201.

Bullo V, Bergamin M, Gobbo S, et al. The effects of Pilates exercise training on physical fitness and wellbeing in the elderly: A systematic review for future exercise prescription. Prev Med. 2015;75:1–11. 2015/03/17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.03.002.

Raafs BM, Karssemeijer EGA, Van der Horst L, et al. Physical exercise training improves quality of life in healthy older adults: a meta-analysis. J Aging Phys Act. 2020;28:81–93. 2019/10/20. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.2018-0436.

Park SH, Han KS, Kang CB. Effects of exercise programs on depressive symptoms, quality of life, and self-esteem in older people: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Appl Nurs Res. 2014;27:219–26. 2014/03/08. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2014.01.004.

Miyazaki R, Takeshima T, Kotani K. Exercise intervention for anti-sarcopenia in community-dwelling older people. J Clin Med Res. 2016;8:848–53. 2016/11/11. https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr2767w.

Martins AC, Santos C, Silva C, et al. Does modified otago exercise program improves balance in older people? a systematic review. Prev Med Rep. 2018;11:231–9. 2018/09/14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.06.015.

Youkhana S, Dean CM, Wolff M, Sherrington C, Tiedemann A. Yoga-based exercise improves balance and mobility in people aged 60 and over: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2016;45:21–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afv175.

Plummer M, Bradley C. Tai chi as a falls prevention strategy in older adults compared to conventional physiotherapy exercise: a review. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2017;24:239–47. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijtr.2017.24.6.239.

Predovan D, Julien A, Esmail A, et al. Effects of dancing on cognition in healthy older adults: a systematic review. J Cogn Enhanc. 2019;3:161–7. 2019/01/01. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-018-0103-2.

Pietrzak E, Cotea C, Pullman S. Using commercial video games for falls prevention in older adults: the way for the future? J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2014;37:166–77. 2014/01/11. https://doi.org/10.1519/JPT.0b013e3182abe76e.

Pacheco TBF, de Medeiros CSP, de Oliveira VHB, et al. Effectiveness of exergames for improving mobility and balance in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2020;9:163. 2020/07/20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01421-7.

Kinne BL, Finch TJ, Macken AM, Smoyer CM Using the Wii to improve balance in older adults: a systematic review. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr 2015; 33: 363–375. https://doi.org/10.3109/02703181.2015.1100697.

Teng B, Gomersall SR, Hatton A, et al. Combined group and home exercise programmes in community-dwelling falls-risk older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiother Res Int. 2020;25:e1839. 2020/05/13. https://doi.org/10.1002/pri.1839.

Arrieta H, Rezola-Pardo C, Gil SM, et al. Physical training maintains or improves gait ability in long-term nursing home residents: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Maturitas. 2018;109:45–52. 2018/02/18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.12.003.

Orellano E, Colon WI, Arbesman M. Effect of occupation- and activity-based interventions on instrumental activities of daily living performance among community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther. 2012;66:292–300. 2012/05/03. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2012.003053.

Miller KJ, Suarez-Iglesias D, Varela S, et al. Exercise for nonagenarians: a systematic review. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2020;43:208–18. 2019/10/01. https://doi.org/10.1519/JPT.0000000000000245.

Loya JC. Systematic review of physical activity interventions in Hispanic adults. Hisp Health Care Int. 2018;16:174–88. 2018/11/27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1540415318809427.

Mody L, Miller DK, McGloin JM, et al. Recruitment and retention of older adults in aging research. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:2340–8. 2008/12/20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02015.x.

Ejiogu N, Norbeck JH, Mason MA, et al. Recruitment and retention strategies for minority or poor clinical research participants: lessons from the Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity across the Life Span study. Gerontologist. 2011;51(Suppl 1):S33–45. 2011/05/20. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnr027.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable feedback received from the following leading researchers:

Professor Heather McKay, University of British Columbia, Canada.

Professor Dafna Merom, University of Western Sydney, Australia.

Professor Ben Smith, University of Sydney, Australia.

Tweet

-

Published @IJBNPA review of #PhysicalActivity interventions for #OlderAdults @msk_health @WHO @jentayloryoga (99 characters)

-

Positive findings for increasing total PA & PA programmes. More research needed for referral, environment, sport, social participation & well-being in older people. (274 char)

Funding

This scoping review was funded by the Physical Activity Unit, Department of Health Promotion, Division of Universal Health Coverage and Healthier Populations, World Health Organization (WHO). WHO reviewed the terms of reference and deliverables.

Professor Catherine Sherrington, Associate Professor Anne Tiedemann, Dr. Leanne Hassett and Dr. Marina Pinheiro are also supported by grants and research fellowships from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), Australia. These funding bodies had no role in this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CS, JT and AT designed the study. JT wrote the protocol and performed the searches. JT and SW performed title and abstract screening. JT, SW, JSO, and MP performed full text screening. JT, SW, WK and LH extracted and coded the data. CS, AT, AB, LH, JSO and MP provided critical manuscript feedback. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable to this scoping review of systematic reviews.

Consent for publication

This scoping review does not contain any individual person’s data in any form (including any individual details, images or videos).

Conflict of Interest

Dr Fiona Bull leads the Physical Activity Unit, Department of Health Promotion, Division of Universal Health Coverage and Healthier Populations, World Health Organization (WHO). The authors were funded by WHO to undertake this review.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Taylor, J., Walsh, S., Kwok, W. et al. A scoping review of physical activity interventions for older adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 18, 82 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-021-01140-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-021-01140-9