Abstract

Background

Knowledge management (KM) emerged as a strategy to promote evidence-informed decision-making. This scoping review aims to map existing KM tools and mechanisms used to promote evidence-informed health decision-making in the WHO European Region and identify knowledge gaps.

Methods

Following the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidance for conducting scoping reviews, we searched Medline, PubMed, EMBASE, the Cochrane library, and Open Grey. We conducted a descriptive analysis of the general characteristics of the included papers and conducted narrative analysis of the included studies and categorized studies according to KM type and phase.

Results

Out of 9541 citations identified, we included 141 studies. The KM tools mostly assessed are evidence networks, surveillance tools, observatories, data platforms and registries, with most examining KM tools in high-income countries of the WHO European region. Findings suggest that KM tools can identify health problems, inform health planning and resource allocation, increase the use of evidence by policymakers and stimulate policy discussion.

Conclusion

Policymakers and funding agencies are called to support capacity-building activities, and future studies to strengthen KM in the WHO European region particularly in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. An updated over-arching strategy to coordinate KM activities in the WHO European region will be useful in these efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is increased awareness and need among policymakers on the use of the best available research evidence and data to guide public health and health systems decisions. Barriers to evidence-informed policymaking included the large volume of evidence available and poor access to research [1, 2]. Knowledge management (KM) emerged as a strategy to promote evidence-informed decision-making as it is considered a way to provide the right information, to the right person, at the right time [3]. It involves the use of the most effective ways to create, share, translate and apply knowledge (tacit and explicit) in order to create value and improve effectiveness, as well as the enabling culture, processes and tools needed to do so [4, 5]. KM tools and strategies are essential to ensure easy access to information, tailored and targeted knowledge, effective dissemination and sharing among knowledge users [6]. In 2005, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched its global KM and its operational plan with the aim of strengthening national health systems through better KM, establishing KM in public health, and enabling WHO to become a better learning organization [5, 7]. The importance of knowledge generation, translation and dissemination was emphasized in the WHO thirteenth general programme of work (GPW13) covering the period 2019–2025 [8].

KM is central to achievement of Sustainable Development Goals by bridging the know-do gap and strengthening health systems. Effective KM tools and mechanisms can strengthen national health information systems through reducing data collection burden and proper management and use of big data to complement traditional methods for timely measurement and monitoring of health status and health system performance [9].

The COVID-19 pandemic has proved more than ever the importance of KM. The European Program of Work 2020–2025 emphasized the critical need for countries to strengthen their health data and information systems to ensure that decisions are data driven and facilitate public health monitoring [10]. In times of crisis, decisions are critical and the effectiveness of these decisions depends on effective KM systems which is the capacity to create, share, collect, transfer, and elaborate knowledge [11].

To our knowledge, there is no previous work that mapped KM initiatives, tools and mechanisms in the WHO European Region. This scoping review aims to map, identify knowledge gaps and provide an overview of available research evidence on existing KM tools and mechanisms used to promote evidence-informed decision-making in the WHO European Region. It also aims to examine implementation considerations and reported outcomes of the identified KM tools and mechanisms in public health, specifically health systems, in terms of promoting evidence-informed decision-making.

Materials and methods

Protocol and registration

We registered the protocol for this scoping review in Open Science Framework https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/Q2GTU.

Definitions

A scoping review is typically used to present “a broad overview of the evidence pertaining to a topic, irrespective of study quality, to examine areas that are emerging, to clarify key concepts and to identify gaps”. We used the updated Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidance for conducting scoping reviews [12]. We also followed the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) for reporting scoping reviews [13].

Eligibility criteria

We included studies on KM tools and mechanisms based on traditional and digital data sources (e.g. communities of practice, networks, online registries, portals, information repositories, clinical guidelines or best practices, discussion forums, social media, electronic libraries, policy briefs). KM involves [14]:

-

knowledge generation (knowledge acquisition, creation),

-

knowledge storage (knowledge assimilation, package, documentation),

-

knowledge processing (knowledge synthesis, integration, refinement),

-

knowledge transfer (knowledge sharing, exchange, dissemination, brokering and translation),

-

knowledge utilization.

We included studies that assess, examine or describe the role or the impact of the knowledge management tools and mechanisms on health policies and decision-making. We considered public policy that is any statement or position taken by the government or government departments. We excluded studies on knowledge management tools in clinical setting or health business or implemented at organizational level. We included primary studies, narrative reviews, systematic reviews, editorials and commentaries. We restricted our eligibility criteria to articles and reports published after the year 2005. We excluded protocols and abstracts of meetings and conferences. We restricted to studies focusing on the WHO European region (see Additional file 1: Appendix 1).

Literature search

We searched the following electronic databases: Ovid Medline, PubMed, EMBASE, the Cochrane library, and Open Grey. We used both index terms and free text words for the three following concepts: knowledge management, policy and Europe. The search terms and MeSH terms for each database were developed with the guidance of an information specialist and with input from experts in KM. We also mapped studies and report on KM to identify additional search terms. We did not limit the search to specific languages. For articles in languages different than English, we used DeepL Translator (https://www.deepl.com/translator) to translate articles to English language. We ran the search from January 2005 till September 2022. We chose to restrict our search to 2005 as this year marks the rise of the “web 2.0” which had major implications on the internet in general and on knowledge management [15]. Search strategies are found in Additional file 2: Appendix 2.

Selection process

We imported the results into Covidence (https://www.covidence.org/) where we conducted the selection process in two stages. Teams of two reviewers used the above eligibility criteria to screen titles and abstracts of identified citations in duplicate and independently for potential eligibility. We retrieved the full text for citations judged as potentially eligible by at least one of the two reviewers. Same teams of reviewers screened the full texts in duplicate and independently and resolved disagreements by discussion or with the help of a third reviewer. We pilot tested screening forms and conducted calibration exercises with a subset of studies to ensure the eligibility criteria are clear and reviewers are on high-level of agreement in the selection process.

Data charting and synthesis

One reviewer abstracted data using standardized and pilot tested forms and another reviewer validated the extraction. The reviewers resolved any disagreement by discussion and when needed with the help of a third reviewer. We conducted pilot testing of the data extraction form to ensure the clarity and validity of the data abstraction process.

We extracted from each paper information on first authors (e.g. name and country of affiliation), year, language and type of publication, study design, setting (e.g. country(ies) subject of the paper and income level classification according to the World Bank list of economies issued in June 2021), characteristics of the intervention (type of KM tools/mechanisms, details, geographical/jurisdictional level, phase of KM (knowledge generation, storage, processing, transfer and utilization), key results, policy or decision examined (e.g. policies such as pharmaceutical policies, strategies, national health plans, national programs), statements on funding and conflict of interest of authors.

We conducted descriptive analysis of the general characteristics of the included papers including intervention, study designs, settings and outcome. We also conducted narrative analysis of the included studies and categorized studies according to KM type and phase.

Risk of bias assessment

We did not conduct risk of bias assessment and methodological assessment of the quality of evidence, which is consistent with the Joanna Briggs Institute guidance manual.

Results

Study selection

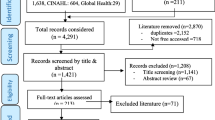

Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flowchart that summarizes the results of the search and selection process. Out of 9541 citations identified from electronic databases, we included 141 studies. At the full text screening, we excluded 684 articles for the following reasons: not outcome of interest (n = 324), not intervention of interest (n = 173), not design of interest (n = 104), missing full text (n = 48), not setting of interest (n = 31) and duplicate (n = 4).

Characteristics of included studies

Table 1 presents the characteristics of included studies. Most of the studies examined KM tools in high-income countries of the WHO European region (n = 70; 49.6%) followed by studies examining knowledge management tools at a regional level or across different countries in the WHO European region (n = 68; 48.2%). Studies were mainly conducted by authors based in high-income European countries (n = 135; 95.7%). Many of the studies were descriptive case studies or employed observational study design. The KM tools mostly assessed in included studies were evidence networks and collaborations (n = 32; 22.7%) followed by surveillance tools, observatories, and data platforms (n = 23; 16.3%), and registries (n = 21; 14.9%). Most of the studies were reported as funded (n = 77; 51.8%) and reported no conflict of interest of authors (n = 73; 51.8%).

Findings

Figure 2 summarizes the study findings briefly. We provide below the narrative analysis of the findings categorized by KM phase and type. We presented the implementation considerations including barriers and facilitators contributing to the successful implementation of the different KM tools in Table 2.

Knowledge generation

Indicators (n = 8)

Eight studies assessed the role of indicators in evidence-informed policymaking (Additional file 3: Appendix 3). The indicators examined in the studies are EURO-HEALTHY PHI [16], HLY—a disability-free life expectancy, the GALI [17], ECHIM [18], ECHI [19], measurable indicators for evidence-informed policy-making developed by REPOPA project [20], key performance indicators (KPIs) in regional-level health-care systems [21]. Indicators such as HLY, DALY and GALI indicators were used to set policy targets, develop strategies in health such as national health plans and design policies and programs and evaluate national programs and service provision [17, 22, 23].

Surveys (n = 3)

Three studies assessed the use of surveys and randomized controlled trials in generating knowledge to inform policy and health planning [24,25,26] (Additional file 4: Appendix 4). The European health examination surveys (HES) have the potential to identify priorities health problems to be addressed and can be used for health monitoring.

Knowledge storage

Registries (n = 21)

Twenty-one studies focused on the role of registries in decision-making (Additional file 5: Appendix 5). Cancer registries, at the national and regional levels, received special attention among registries targeting specific diseases and were found to help establish public health priorities, guide resource allocation, inform decisions regarding reimbursement, access and care delivery and support planning and evaluation of health services [27,28,29,30,31].

Other registries included rare disease registries [32,33,34,35,36], registries addressing neurological and neurodevelopmental diseases such as multiple sclerosis [37] and autism [38] and registries on infectious diseases [39] and non-communicable diseases [40,41,42]. These registries enabled health authorities and policymakers to identify at-risk groups for which targeted care is needed and to develop programs responsive to the patients’ needs and supports the planning and implementation of public health policies toward disease management and control. Aside from the role assumed by registries in disease management and service delivery, population registries can support governmental and authoritative decisions such as planning and resource allocation and measures such as taxation, allowance, and subsidies [43]. Data generated through registries can also be used for the regulation of medical supplies and the medical profession [44, 45].

Surveillance tools, observatories, and data platforms (n = 24)

Twenty-four studies on surveillance, observatories, and data platforms were included in the review (Additional file 6: Appendix 6). Surveillance systems were an integral part of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Denmark and Italy through guiding the national policies [46] and analyzing the pandemic evolution [47]. Similarly, the West Nile virus surveillance system in Italy and the Portuguese Tuberculosis Surveillance System were developed to guide public health policies designed to mitigate the risk of disease transmission [48, 49]. Health surveillance systems in Germany of emergency admissions enables continuous monitoring of relevant health phenomena issues thus can guide evidence-informed decision-making [50, 51].

Three studies found that observatories can monitor health systems performance [52], provide policy options for the development of several health-related policies such as funding of long-term care and anti-tobacco policies, through packaging and sharing information with policymakers [53] and promote common methods for responding to global eHealth challenges [54].

Data platforms can also support policy and decision-making on drug regulation [55] and other health issues such as childhood obesity, tobacco, nutrition and COVID-19 response. Examples of data platforms addressing nutrition issues included the food composition data in the European region [56], and the Nutri-RecQuest, a regional data platform in the EU [57]. Other data platforms included the BigO tool in Greece, Sweden, and Ireland [58], European Health Information Gateway [59], the Big Data platform [60, 61], the Climate-Environment-Health data mashup [62], the ADR NI Database [63], the Atlas of Cardiology [64], the web portals deployed during COVID-19 [65], EUPHIX [66], e-labs [67] and the European Service Mapping Schedule/Description and Evaluation of Services and DirectoriEs system [68].

Health information systems (n = 4)

Four studies discussed the essential role of health information systems in the EU in providing the base for health planning and policymaking (Additional file 7: Appendix 7). All of these studies discussed health information systems at the regional level of the EU. These studies highlighted the fragmentation and diversity of health information systems across EU and the need to harmonize and standardize and ensure systematic data collection and reporting [69,70,71] and the need to leverage on digital health [65]. One study discussed the need to integrate information on refugees and migrants within the health information systems in the EU to allow for better health planning [69].

Knowledge processing

Evidence synthesis (n = 19)

Nineteen studies examined the role of evidence synthesis in informing policies and decisions in Europe (Additional file 8: Appendix 8). Evidence briefs for policy, evidence guides, context-specific evidence summaries, scoping and rapid reviews and plain language summaries of systematic reviews can play a role in informing strategies, plans and decisions [72,73,74,75,76] and considered as a credible and useful source of information [77, 78]. Demand-led evidence briefing service, a resource-intensive service, was not associated with increases in NHS commissioners capacity to acquire, assess, adapt and apply research evidence to support decision-making compared with less intensive and less targeted strategies [79]. Included studies showed that HTA [80,81,82,83], CED schemes [84, 85], evidence-based national guidelines [86] and DECIDE tool [87] can inform resource allocation and reimbursement decisions to create the most value for money. Data mining and public health triangulation was also identified as tools to support decision-making in public health [88, 89].

Health reports and toolkits (n = 5)

Five studies examined how health reports and toolkits can support in monitoring health systems, developing and implementing national policies and influencing decision-making process [90,91,92,93] (Additional file 9: Appendix 9). The health reports and toolkits identified in the included studies were the WHO HEN reports and the European Health Report published at the WHO Europe level [59, 91], the health care performance report [90], the Public Health Status and Foresight report published in the Netherlands [92] and the Healthy Eating and Physical Activity in Schools toolkit [93].

Knowledge transfer

Policy dialogue and stakeholder involvement (n = 17)

Seventeen studies examined how policy dialogues and stakeholder involvement can inform decision-making (Additional file 10: Appendix 10). Policy dialogues and stakeholder involvement, at the national and sub-national levels, can increase the use of research evidence by policymakers, increased policymaker’s awareness, facilitated interaction between a range of stakeholders across different sectors, provided conducive environment for discussion of timely and relevant summarized evidence and led to adoption, development and changes in policies and strategies [94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110]. Included studies reported that the dialogues were informed by evidence such as HTA, systematic reviews and context-specific reports.

Evidence networks and collaborations (n = 32)

Evidence networks and collaborations promote partnerships between key stakeholders including policymakers, researchers, and academic bodies to inform public policy (Additional file 11: Appendix 11). Evidence networks across Europe such as the HENVINET [111, 112], the HEN [113], EVIPNet [114, 115], Burden-eu [116], EurOOHnet [117], the European network on human biomonitoring [118], the HBM4EU and BRIDGE health [119] and other stakeholders networks and knowledge brokering activities [120,121,122] are able to support decision makers across key public health issues such as context-specific diet and nutrition policies [113] and pharmaceutical policies [123]. The EUnetHTA, HTAB and epistemic communities also facilitated linking the HTA evidence to policymaking [123,124,125,126,127].

National evidence networks such as the Finnish National Healthy Cities Network, the Knowledge Transfer Partnership in Scotland, the Share-Net in the Netherlands and Life Science Exchange project contributed to the development, implementation and evaluation of health policies and services [128,129,130,131]. Other national evidence networks and expert committees provided policy advice during the COVID-19 pandemic [132,133,134]. Collaborations at the research and academic levels act as KM tools and form an evidence base for public health policy and practice [135, 136]. AskFuse, a knowledge brokering service provided a platform for collaboration between researchers and policymakers [137]. Two studies reported on policy games simulations, bringing policymakers together to jointly develop a policy implementation plan [138, 139].

Community engagement (n = 5)

Five studies examined the influence of community engagement on decision-making (Additional file 12: Appendix 12). Community engagement can provide evidence to policymakers to ensure health reforms included a focus on social determinants of health [140], ensure health services are designed to meet the needs of the targeted population [141, 142], refine service delivery [143] and inform national policies on controlling alcohol availability [144].

Decision support tools (n = 5)

DSTs can play an important role in transferring information and knowledge to policy and decision makers on road safety, health services, environmental and urban health [145,146,147,148,149] (Additional file 13: Appendix 13). DSTs assessed in the included studies were the CRAFT tool [148], the HENVINET DST MDB [150], the NHS Scotland DST Platform [148], the SOMNet, combined with the EbCA [149] and the European Road Safety Decision Support System [147].

Discussion

This scoping review maps the evidence on KM tools and mechanisms aiming at influencing policy decisions-making and promoting evidence-informed decision-making in the WHO European Region. It identifies 141 studies assessing different KM tools and mechanisms. Findings suggest that knowledge management tools can identify health problems, inform health planning and resource allocation and can be used for health monitoring. Most of the included studies stressed on the importance of the availability of resources, the sustainability and the institutionalization of the use of KM tools and mechanisms in order to promote the use of evidence and knowledge generated in decision making. Political commitment and creating the adequate culture are essential to increase the uptake of evidence generated from different KM tools and mechanisms.

The KM tools mostly assessed were evidence networks and collaborations, surveillance tools, observatories, and data platforms and registries. The majority of the studies examined knowledge management tools implemented in high-income countries of the WHO European region. This finding can be interpreted by the fact that research and work on KM in other parts of the WHO European Region is still in its earliest phase. It can also be explained by the limited resources available in these countries to invest in KM.

Many studies examined KM tools at a regional level, which shows initiatives at the WHO European region level to invest and advance the work on KM. This finding is validated by the range of evidence networks and collaborations that was identified in this review such as HENVINET, EVIPNet, EUnetHTA, HBM4EU and BRIDGE Health. The majority of the included studies were conducted by authors based in high-income Europe. This finding shows the imbalance in research capacities between high-income and low and middle-income countries in the WHO European region.

The majority of the studies employed descriptive case study or observational designs as opposed to experimental studies. This can be interpreted by the difficulty of applying experimental design and the multiple and complex factors that affect the policymaking process which make it hard to evaluate the direct impact of KM tools and mechanisms on decision-making.

Ensuring data quality, harmonization and completeness and regularity of data collection was reported as a key factor for the success of health information systems, registries, surveillance tools, observatories, and data platforms. These pillars would allow comparability of data across countries across the WHO European Region and over time. Integrating all sections of the population such as refugees, migrants, and other marginalized or disadvantaged population was reported to be essential for better health planning [153]. These findings call for supporting work in Central Asia (CA) and Eastern Europe (EE) in data harmonization and completeness as part of health information systems strengthening outlined in the EPW and GPW13 and as a catalyst in the development of KM platforms and tools.

Plain language summaries of systematic reviews, evidence briefing services, scoping and rapid reviews were found to be useful sources of information for policymakers. Researchers and institutions working in developing those summaries should take into consideration the applicability of the evidence to the context, the difficulties of the statistical and scientific terms, the length of the summary and the language. Evidence synthesis was shown to support decision-making in other regions [154] and mainly during COVID-19 [155].

Evidence networks and collaborations across Europe were also found to support decision-makers across key public health issues. These evidence networks were also shown to support decision-making in other jurisdictions such as the Americas [156]. Policy dialogues were shown to increase the use of research evidence by policymakers, increased policymaker’s awareness and stimulate discussion on the issue raised during the dialogue and facilitated the interaction between a range of stakeholders across different sectors [157, 158]. To ensure desired impact from the dialogues, there is a need to conduct periodic dialogues, follow up with stakeholders afterwards and recognize the role of contextual factors and ensure availability of resources for implementation. In addition to engaging stakeholders, engaging communities is essential to include the voice of citizens in policymaking. However, most of the studies on policy dialogues showed that these dialogues are conducted mainly at national levels as opposed to conducting them at a regional level (i.e. WHO European Region).

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to map the published evidence on KM tools and mechanisms aiming at influencing decision making in the WHO European Region. One strength of the study is that we followed Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidance for conducting scoping reviews [12] and we followed the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) for reporting scoping reviews [13]. Our scoping review has three main limitations. The first limitation is that we did not search Russian-language scientific databases so we might have missed studies conducted in Russian-speaking countries. Second limitation is that the framework we used consider knowledge translation as part of knowledge management. While we consider the knowledge translation as a sub-set of knowledge management, we acknowledge the distinct focused, scopes and processes of knowledge translation within the larger framework of knowledge management. Third, we acknowledge that our search strategy might have missed certain types of KM tools such as the Evidence to Decision (EtD) framework due to the restriction to certain names of KM tools in the search strategy.

Implications for research and policy

This scoping review can inform researchers and funders interested in understanding the role of KM tools and mechanisms in influencing health decision-making mainly in the WHO European region. While we acknowledge the challenges of measuring the effectiveness of knowledge management tools on decision making, researchers are encouraged to conduct better-designed and rigorous research studies to assess this relationship to inform efforts aiming at promoting evidence-informed decision-making in this region mainly in CA and EE countries. Researchers are also called to develop and follow guidelines for designing and reporting studies evaluating the effectiveness or impact of KM tools and mechanisms. Our scoping review can also inform the work researchers aiming at mapping KM initiatives, tools and mechanisms in other WHO regions.

As plain language summaries, policy dialogues and evidence networks were shown to increase the use of research evidence by policymakers and stimulate discussion on policy issues, funders are called to support capacity-building activities in this aspect, particularly in the eastern part of the WHO European Region, where research production and KM activities are still at their early stages. Given that most studies on KM systems, tools, and platforms found were from high-income countries in Western Europe, there is a need for further understanding the needs of the CA and EE countries for KM platforms and systems, and accordingly conduct twinning and knowledge exchange activities between high income countries with developed KM systems and platforms with countries who still lag behind. The findings also highlight the need to institutionalize the use of evidence in decision-making and leverage on existing KM tools and mechanism to inform health policies and national strategies.

Health systems managers and policymakers are called to ensure data availability, completeness, and standardization of data collection and reporting mechanisms to improve their country’s health information systems and the work of registries, surveillance tools and observatories. These KM tools would allow for better health planning including resource allocation and reimbursement decisions.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its Additional files.

Abbreviations

- DSTs:

-

Decision support tools

- HENVINET DST MDB:

-

Health and Environment Network Decision Support Tools Metadata Base

- CRAFT:

-

Cities Rapid Assessment Framework for Transformation

- GIFT:

-

Global Individual Food consumption data Tool

- ADR NI:

-

Administrative Data Research Northern Ireland

- EUPHIX:

-

European Public Health Information and Knowledge System

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- HEN:

-

Health Evidence Network

- HTA:

-

Health Technology Assessment

- CED:

-

Coverage with Evidence Development

- Burden-eu:

-

European Burden of Disease Network

- HBM4EU:

-

European human biomonitoring initiative

- ECHI:

-

European Core Health Indicators

- PHI:

-

Population Health Index

- ECHIM:

-

European Community Health Indicators & Monitoring

- REPOPA:

-

REsearch into POlicy to enhance Physical Activity

- GALI:

-

Global Activity Limitation Indicator

- SOMNet:

-

Self-organising map network

- EbCA:

-

Expert-based collaborative analysis

- HLY:

-

Healthy Life Years

- HENVINET:

-

Health and Environment Network

References

LaPelle NR, Luckmann R, Simpson EH, Martin ER. Identifying strategies to improve access to credible and relevant information for public health professionals: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:89.

Oliver K, Innvar S, Lorenc T, Woodman J, Thomas J. A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:2.

Dobbins M, DeCorby K, Robeson P, Husson H, Tirilis D, Greco L. A knowledge management tool for public health: health-evidence. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):496.

Kothari A, Hovanec N, Hastie R, Sibbald S. Lessons from the business sector for successful knowledge management in health care: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(1):173.

WHO. World Health Organization: knowledge management global operational plan, 2006–2007. World Health Organization; 2006.

Quinn E, Huckel-Schneider C, Campbell D, Seale H, Milat AJ. How can knowledge exchange portals assist in knowledge management for evidence-informed decision making in public health? BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):443.

WHO. WHO Global Knowledge Management Strategy 2005.

WHO. Thirteenth general programme of work 2019–2023 World Health Organization 2019.

McCullum C, Pelletier D, Barr D, Wilkins J. Agenda setting within a community-based food security planning process: the influence of power. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2003;35(4):189–99.

WHO/Europe. The European Program of Work 2020–2025 World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe 2021.

Ammirato S, Linzalone R, Felicetti AM. Knowledge management in pandemics. A critical literature review. Knowl Manage Res Pract. 2020:1–12.

Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10).

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Yazdani S, Bayazidi S, Mafi AA. The current understanding of knowledge management concepts: a critical review. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2020;34:127.

O'reilly T. What is Web 2.0: Design patterns and business models for the next generation of software. Commun Strat. 2007(1):17.

Costa C, Freitas Â, Stefanik I, Krafft T, Pilot E, Morrison J, et al. Evaluation of data availability on population health indicators at the regional level across the European Union. Popul Health Metr. 2019;17(1):N.PAG-N.PAG.

Bogaert P, Van Oyen H, Beluche I, Cambois E, Robine JM. The use of the global activity limitation Indicator and healthy life years by member states and the European Commission. Arch Public Health. 2018;76:30.

Verschuuren M, Gissler M, Kilpelainen K, Tuomi-Nikula A, Sihvonen AP, Thelen J, et al. Public health indicators for the EU: the joint action for ECHIM (European Community Health Indicators & Monitoring). Arch Public Health. 2013;71(1):12.

Fehr A, Tijhuis MJ, Hense S, Urbanski D, Achterberg P, Ziese T. European Core Health Indicators—status and perspectives. Arch Public Health. 2018;76:52.

Tudisca V, Valente A, Castellani T, Stahl T, Sandu P, Dulf D, et al. Development of measurable indicators to enhance public health evidence-informed policy-making. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):47.

Berler A, Pavlopoulos S, Koutsouris D. Using key performance indicators as knowledge-management tools at a regional health-care authority level. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2005;9(2):184–92.

Colzani E, Cassini A, Lewandowski D, Mangen MJ, Plass D, McDonald SA, et al. A software tool for estimation of burden of infectious diseases in Europe using incidence-based disability adjusted life years. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(1): e0170662.

Devleesschauwer B, Maertens de Noordhout C, Smit GSA, Duchateau L, Dorny P, Stein C, et al. Quantifying burden of disease to support public health policy in Belgium: opportunities and constraints. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1196.

Cavill N, Foster C, Oja P, Martin BW. An evidence-based approach to physical activity promotion and policy development in Europe: contrasting case studies. Promot Educ. 2006;13(2):104–11.

Volen E, de Laat J. Building evidence for pre-school policy change in Bulgaria. Front Public Health. 2021;9: 594029.

Tolonen H, Koponen P, Al-Kerwi A, Capkova N, Giampaoli S, Mindell J, et al. European health examination surveys—a tool for collecting objective information about the health of the population. Arch Public Health. 2018;76:38.

Sharp L, Deady S, Gallagher P, Molcho M, Pearce A, Alforque Thomas A, et al. The magnitude and characteristics of the population of cancer survivors: using population-based estimates of cancer prevalence to inform service planning for survivorship care. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:767.

Wojcieszak PZ, Poletajew S, Rutkowski D, Radziszewski P. The incidence of renal cancer in Polish National Cancer Registry: is there any epidemiological data we can rely on? Cent European J Urol. 2014;67(3):253–6.

Siesling S, Louwman WJ, Kwast A, van den Hurk C, O’Callaghan M, Rosso S, et al. Uses of cancer registries for public health and clinical research in Europe: Results of the European Network of Cancer Registries survey among 161 population-based cancer registries during 2010–2012. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(9):1039–49.

Mohseninejad L, van Gils C, Uyl-de Groot CA, Buskens E, Feenstra T. Evaluation of patient registries supporting reimbursement decisions: the case of oxaliplatin for treatment of stage III colon cancer. Value Health. 2015;18(1):84–90.

Capozzi M, De Divitiis C, Ottaiano A, Teresa T, Capuozzo M, Maiolino P, et al. Funds reimbursement of high-cost drugs in gastrointestinal oncology: an italian real practice 1 year experience at the National Cancer Institute of Naples. Front Public Health. 2018;6:291.

Jonker CJ, de Vries ST, van den Berg HM, McGettigan P, Hoes AW, Mol PGM. Capturing data in rare disease registries to support regulatory decision making: a survey study among industry and other stakeholders. Drug Saf. 2021;44(8):853–61.

Stanimirovic D, Murko E, Battelino T, Groselj U. Development of a pilot rare disease registry: a focus group study of initial steps towards the establishment of a rare disease ecosystem in Slovenia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14(1):172.

Stanimirovic D, Murko E, Battelino T, Groselj U. Charting early developmental trajectory of a pilot rare disease registry in Slovenia. Stud Health Technol Informat. 2020;272:213–6.

Taruscio D, Kodra Y, Ferrari G, Vittozzi L, National Rare Diseases Registry Collaborating G. The Italian National Rare Diseases Registry. Blood Transf. 2014;12(Suppl 3):S606–13.

Pricci F, Villa M, Maccari F, Agazio E, Rotondi D, Panei P, et al. The Italian Registry of GH Treatment: electronic Clinical Report Form (e-CRF) and web-based platform for the national database of GH prescriptions. J Endocrinol Invest. 2019;42(7):769–77.

Mohammadzadeh N, Ghazanfarisavadkoohi E, Khenarinezhad S, Safari MS. Requirements of the national multiple sclerosis disease registry system: a review of experiences. Gazi Med J. 2020;32(1):154–60.

Murillo L, Shih A, Rosanoff M, Daniels AM, Reagon K. The role of multi-stakeholder collaboration and community consensus building in improving identification and early diagnosis of autism in low-resource settings. Aust Psychol. 2016;51(4):280–6.

Rossi P, Tamarozzi F, Galati F, Pozio E, Akhan O, Cretu CM, et al. The first meeting of the European Register of Cystic Echinococcosis (ERCE). Parasit Vectors. 2016;9(1).

Carinci F, Iorio T, Benedetti M. Standardized information exchange in diabetes: integrated registries for Governance, Research, and Clinical Practice. Front Diabetes. 2015;24:236–49.

report Urrta. UK renal registry 11th annual report (2008): Appendix A the UK renal registry statement of purpose. Nephron—Clinical Practice. 2009;111(Suppl 1):c287-c92.

Report URRtA. UK Renal Registry 19th Annual Report: Appendix A The UK Renal Registry Statement of Purpose. Nephron. 2017;137(Suppl 1):327–32.

Ludvigsson JF, Almqvist C, Bonamy AK, Ljung R, Michaëlsson K, Neovius M, et al. Registers of the Swedish total population and their use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(2):125–36.

Mandavia R, Knight A, Carter AW, Toal C, Mossialos E, Littlejohns P, et al. What are the requirements for developing a successful national registry of auditory implants? A qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(9): e021720.

Ornerheim M. Policymaking through healthcare registries in Sweden. Health Promot Int. 2018;33(2):356–65.

Schonning K, Dessau RB, Jensen TG, Thorsen NM, Wiuff C, Nielsen L, et al. Electronic reporting of diagnostic laboratory test results from all healthcare sectors is a cornerstone of national preparedness and control of COVID-19 in Denmark. APMIS. 2021;129(7):438–51.

Sartor G, Del Riccio M, Dal Poz I, Bonanni P, Bonaccorsi G. COVID-19 in Italy: considerations on official data. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;98:188–90.

Paternoster G, Martins SB, Mattivi A, Cagarelli R, Angelini P, Bellini R, et al. Economics of One Health: costs and benefits of integrated West Nile virus surveillance in Emilia-Romagna. PLoS One. 2017;12(11).

Seabra B, Duarte R. Tuberculosis national registries and data on diagnosis delay—is there room for improvement? Pulmonology. 2021.

Ziese T, Hamouda O. Surveillance and monitoring—results of the working group 10 of the forum future Public Health, Berlin 2016. Gesundheitswesen. 2017;79(11):932–5.

Grabenhenrich Mph L, Schranz M, Boender S, Kocher T, Esins J, Fischer M. Real-time data from medical care settings to guide public health action. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2021;64(4):412–7.

Busse R, van Ginneken E. Cross-country comparative research—lessons from advancing health system and policy research on the occasion of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies’ 20th anniversary. Health Policy. 2018;122(5):453–6.

Lavis JN, Permanand G, Catallo C, Bridge Study T. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies European Observatory Policy Briefs. 2013.

Stroetmann KA, Middleton B. Policy needs and options for a common transatlantic approach towards measuring adoption, usage and benefits of eHealth. Stud Health Technol Informat. 2011;170:17–48.

Sultana J, Trotta F, Addis A, Brown JS, Gil M, Menniti-Ippolito F, et al. Healthcare database networks for drug regulatory policies: international workshop on the Canadian, US and Spanish Experience and Future Steps for Italy. Drug Saf. 2020;43(1):1–5.

Egan MB, Fragodt A, Raats MM, Hodgkins C, Lumbers M. The importance of harmonizing food composition data across Europe. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;61(7):813–21.

Cavelaars AEJM, Kadvan A, Doets EL, Tepšić J, Novaković R, Dhonukshe-Rutten R, et al. Nutri-RecQuest: a web-based search engine on current micronutrient recommendations. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64(2):S43–7.

Diou C, Sarafis I, Papapanagiotou V, Alagialoglou L, Lekka I, Filos D, et al. BigO: a public health decision support system for measuring obesogenic behaviors of children in relation to their local environment. Appetite. 2021;157.

Blessing V, Davé A, Varnai P. Evidence on mechanisms and tools for use of health information for decision-making. Copenhagen: World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe; 2017 2017.

Gutenberg J, Katrakazas P, Trenkova L, Murdin L, Brdaric D, Koloutsou N, et al. Big data for sound policies: toward evidence-informed hearing health policies. Am J Audiol. 2018;27(3S):493–502.

Heitmueller A, Henderson S, Warburton W, Elmagarmid A, Pentland AS, Darzi A. Developing public policy to advance the use of big data in health care. Health Aff. 2014;33(9):1523–30.

Fleming LE, Haines A, Golding B, Kessel A, Cichowska A, Sabel CE, et al. Data mashups: potential contribution to decision support on climate change and health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(2):1725–46.

O’Reilly D, Bateson O, McGreevy G, Snoddy C, Power T. Administrative Data Research Northern Ireland (ADR NI). Int J Popul Data Sci. 2020;4(2):1148.

Tofield A. A new European Society of Cardiology research database: Atlas of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(10):801.

Pérez Sust P, Solans O, Fajardo JC, Medina Peralta M, Rodenas P, Gabaldà J, et al. Turning the crisis into an opportunity: digital health strategies deployed during the COVID-19 outbreak. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2): e19106.

Achterberg PW, Kramers PGN, Van Oers HAM. European community health monitoring: the EUPHIX-model…European Public Health Information and Knowledge System. Scand J Public Health. 2008;36(7):676–84.

Couch P, O’Flaherty M, Sperrin M, Green B, Balatsoukas P, Lloyd S, et al. e-Labs and the stock of health method for simulating health policies. Stud Health Technol Informat. 2013;192:288–92.

Romero-López-Alberca C, Gutiérrez-Colosía MR, Salinas-Pérez JA, Almeda N, Furst M, Johnson S, et al. Standardised description of health and social care: a systematic review of use of the ESMS/DESDE (European Service Mapping Schedule/Description and Evaluation of Services and DirectoriEs). Eur Psychiatry. 2019;61:97–110.

Bozorgmehr K, Biddle L, Rohleder S, Puthoopparambil SJ, Jahn R. WHO Health Evidence Network Synthesis Reports. What is the evidence on availability and integration of refugee and migrant health data in health information systems in the WHO European Region? Themed issues on migration and health, X. 2019.

Bogaert P, Van Oyen H. An integrated and sustainable EU health information system: national public health institutes’ needs and possible benefits. Arch Public Health. 2017;75:3.

Bogaert P, van Oers H, Van Oyen H. Towards a sustainable EU health information system infrastructure: a consensus driven approach. Health Policy. 2018;122(12):1340–7.

Anderson JK, Howarth E, Vainre M, Humphrey A, Jones PB, Ford TJ. Advancing methodology for scoping reviews: recommendations arising from a scoping literature review (SLR) to inform transformation of Children and Adolescent Mental Health Services. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20(1):242.

Seidler A, Nusbaumer-Streit B, Apfelbacher C, Zeeb H. fur die Querschnitts. AGRRdKPHzC [Rapid Reviews in the Time of COVID-19—Experiences of the Competence Network Public Health COVID-19 and Proposal for a Standardized Procedure]. Gesundheitswesen. 2021;83(3):173–9.

Murphy A, Šubelj M, Babarczy B, Köhler K, Chapman E, Truden-Dobrin P, et al. An evaluation of the evidence brief for policy development process in WHO EVIPNet Europe countries. Health Res Policy Syst. 2022;20(1):54.

Stansfield J, South J. A knowledge translation project on community-centred approaches in public health. J Public Health. 2018;40(Suppl_1):i57–63.

Martin-Fernandez J, Aromatario O, Prigent O, Porcherie M, Ridde V, Cambon L. Evaluation of a knowledge translation strategy to improve policymaking and practices in health promotion and disease prevention setting in French regions: TC-REG, a realist study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9): e045936.

Kornør H, Bergman H, Maayan N, Soares-Weiser K, Bjørndal A. Systematic reviews on child welfare services: identifying and disseminating the evidence. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015;21(5):855–60.

Busert LK, Mütsch M, Kien C, Flatz A, Griebler U, Wildner M, et al. Facilitating evidence uptake: development and user testing of a systematic review summary format to inform public health decision-making in German-speaking countries. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1).

Wilson PM, Farley K, Bickerdike L, Booth A, Chambers D, Lambert M, et al. Does access to a demand-led evidence briefing service improve uptake and use of research evidence by health service commissioners? A controlled before and after study. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):20.

Jönsson B. Technology assessment for new oncology drugs. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(1):6–11.

Eriksson I, Wettermark B, Persson M, Edström M, Godman B, Lindhé A, et al. The early awareness and alert system in Sweden: history and current status. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8.

Ofori-Asenso R, Hallgreen CE, De Bruin ML. Improving interactions between health technology assessment bodies and regulatory agencies: a systematic review and cross-sectional survey on processes, progress, outcomes, and challenges. Front Med. 2020;7.

Haverinen J, Turpeinen M, Falkenbach P, Reponen J. Implementation of a new Digi-HTA process for digital health technologies in Finland. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2022;38(1): e68.

Federici C, Reckers-Droog V, Ciani O, Dams F, Grigore B, Kalo Z, et al. Coverage with evidence development schemes for medical devices in Europe: characteristics and challenges. Eur J Health Econ. 2021;12:12.

Kovács S, Kaló Z, Daubner-Bendes R, Kolasa K, Hren R, Tesar T, et al. Implementation of coverage with evidence development schemes for medical devices: a decision tool for late technology adopter countries. Health Econ. 2022;31(Suppl 1):195–206.

Fredriksson M, Blomqvist P, Winblad U. Recentralizing healthcare through evidence-based guidelines—striving for national equity in Sweden. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:509.

Parmelli E, Amato L, Saitto C. DECIDE: Developing and evaluating communication strategies to support informed decisions and practice based on evidence. Recenti Prog Med. 2013;104(10):522–31.

Lavrac N, Bohanec M, Pur A, Cestnik B, Debeljak M, Kobler A. Data mining and visualization for decision support and modeling of public health-care resources. J Biomed Inform. 2007;40(4):438–47.

Bossuyt N, Van Casteren V, Goderis G, Wens J, Moreels S, Vanthomme K, et al. Public Health Triangulation to inform decision-making in Belgium. Stud Health Technol Informat. 2015;210:855–9.

Hegger I, Marks LK, Janssen SWJ, Schuit AJ, van Oers HAM. Enhancing the contribution of research to health care policy-making: a case study of the Dutch Health Care Performance Report. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2015;21(1):29–35.

Hanney SR, Kanya L, Pokhrel S, Jones TH, Boaz A. How to strengthen a health research system: WHO’s review, whose literature and who is providing leadership? Health Res Policy Syst. 2020;18(1):72.

Schoemaker CG, van Loon J, Achterberg PW, van den Berg M, Harbers MM, den Hertog FRJ, et al. The Public Health Status and Foresight report 2014: Four normative perspectives on a healthier Netherlands in 2040. Health Policy. 2019;123(3):252–9.

Simovska V, Dadaczynski K, Woynarowska B. Healthy eating and physical activity in schools in Europe. Health Educ. 2012;112(6):513–24.

van Kammen J, Jansen CW, Bonsel GJ, Kremer JA, Evers JL, Wladimiroff JW. Technology assessment and knowledge brokering: the case of assisted reproduction in The Netherlands. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2006;22(3):302–6.

Rassenhofer M, Sprober N, Schneider T, Fegert JM. Listening to victims: use of a Critical Incident Reporting System to enable adult victims of childhood sexual abuse to participate in a political reappraisal process in Germany. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37(9):653–63.

Khan R, Khazaal Y, Thorens G, Zullino D, Uchtenhagen A. Understanding Swiss drug policy change and the introduction of heroin maintenance treatment. Eur Addict Res. 2014;20(4):200–7.

Turner MC, Vineis P, Seleiro E, Dijmarescu M, Balshaw D, Bertollini R, et al. EXPOsOMICS: final policy workshop and stakeholder consultation. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):260.

Ditchburn JL, Marshall A. The Cumbria Rural Health Forum: initiating change and moving forward with technology. Rural Remote Health. 2016;16(2):3738.

Muszbek K. Enhancing Hungarian palliative care delivery. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(5):605–9.

Patera N, Wild C. Linking public health research with policy and practice in three European countries. J Public Health (Germany). 2013;21(5):473–9.

Gouveia J, Coleman MP, Haward R, Zanetti R, Hakama M, Borras JM, et al. Improving cancer control in the European Union: conclusions from the Lisbon round-table under the Portuguese EU Presidency, 2007. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(10):1457–62.

van Kammen J, de Savigny D, Sewankambo N. Using knowledge brokering to promote evidence-based policy-making: the need for support structures. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84(8):608–12.

Giepmans P. EHMA briefing: knowledge mobilization in European Union funded projects—the dialogue model. Health Serv Manage Res. 2013;26(1):38–41.

Bertram M, Loncarevic N, Radl-Karimi C, Thøgersen M, Skovgaard T, Aro AR. Contextually tailored interventions can increase evidence-informed policy-making on health-enhancing physical activity: the experiences of two Danish municipalities. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):14.

Bruen C, Brugha R. “We’re not there to protect ourselves, we’re there to talk about workforce planning”: A qualitative study of policy dialogues as a mechanism to inform medical workforce planning. Health Policy. 2020;124(7):736–42.

Sienkiewicz D, Maassen A, Imaz-Iglesia I, Poses-Ferrer E, McAvoy H, Horgan R, et al. Shaping policy on chronic diseases through national policy dialogs in CHRODIS PLUS. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(19):28.

de Bruin SR, Stoop A, Billings J, Leichsenring K, Ruppe G, Tram N, et al. The SUSTAIN Project: a European study on improving integrated care for older people living at home. Int J Integr Care. 2018;18(1):6.

Jenkins R, Bobyleva Z, Goldberg D, Gask L, Zacroeva AG, Potasheva A, et al. Integrating mental health into primary care in Sverdlovsk. Ment Health Fam Med. 2009;6(1):29–36.

O’Connor S, McGilloway S, Hickey G, Barwick M. Disseminating early years research: an illustrative case study. J Children’s Serv. 2021;16(1):56–73.

Storm I, van Gestel A, van de Goor I, van Oers H. How can collaboration be strengthened between public health and primary care? A Dutch multiple case study in seven neighbourhoods. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):974.

Bartonova A. How can scientists bring research to use: the HENVINET experience. Environ Health Global Access Sci Sour. 2012;11(Suppl 1):S2.

Keune H, Gutleb AC, Zimmer KE, Ravnum S, Yang A, Bartonova A, et al. We’re only in it for the knowledge? A problem solving turn in environment and health expert elicitation. Environ Health Global Access Sci Sour. 2012;11(Suppl 1):S3.

Renzella J, Townsend N, Jewell J, Breda J, Roberts N, Rayner M, et al. WHO Regional Office for Europe WHO Health Evidence Network Synthesis Reports. 2018.

Lester L, Haby MM, Chapman E, Kuchenmuller T. Evaluation of the performance and achievements of the WHO Evidence-informed Policy Network (EVIPNet) Europe. Health Res Policy Syst. 2020;18(1):109.

Mihalicza P, Leys M, Borbas I, Szigeti S, Biermann O, Kuchenmuller T. Qualitative assessment of opportunities and challenges to improve evidence-informed health policy-making in Hungary—an EVIPNet situation analysis pilot. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):50.

Haneef R, Schmidt J, Gallay A, Devleesschauwer B, Grant I, Rommel A, et al. Recommendations to plan a national burden of disease study. Arch Public Health. 2021;79(1):126.

Huibers L, Philips H, Giesen P, Remmen R, Christensen MB, Bondevik GT. EurOOHnet—the European research network for out-of-hours primary health care. Eur J Gen Pract. 2014;20(3):229–32.

Smolders R, Koppen G, Schoeters G. Translating biomonitoring data into risk management and policy implementation options for a European Network on Human Biomonitoring. Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source. 2008;7:S2-S.

David M, Schwedler G, Reiber L, Tolonen H, Andersson AM, Esteban Lopez M, et al. Learning from previous work and finding synergies in the domains of public and environmental health: EU-funded projects BRIDGE Health and HBM4EU. Arch Public Health. 2020;78:78.

Spitters HP, Lau CJ, Sandu P, Quanjel M, Dulf D, Glumer C, et al. Unravelling networks in local public health policymaking in three European countries—a systems analysis. Health Res Policy Syst. 2017;15(1):5.

Butler J, Foot C, Bomb M, Hiom S, Coleman M, Bryant H, et al. The International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership: an international collaboration to inform cancer policy in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Health Policy. 2013;112(1–2):148–55.

Team TBS. European Observatory Health Policy Series. Lavis JN, Catallo C, editors. Copenhagen (Denmark): European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. ©World Health Organization 2013 (acting as the host organization for, and secretariat of, the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies). 2013.

Vogler S, Leopold C, Zimmermann N, Habl C, de Joncheere K. The pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement information (PPRI) initiative-Experiences from engaging with pharmaceutical policy makers. Health Policy Technol. 2014;3(2):139–48.

Kristensen FB, Chamova J, Hansen NW. Toward a sustainable European Network for Health Technology Assessment. The EUnetHTA project. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2006;49(3):283–5.

Kristensen FB, Lampe K, Chase DL, Lee-Robin SH, Wild C, Moharra M, et al. Practical tools and methods for health technology assessment in Europe: structures, methodologies, and tools developed by the European Network for Health Technology Assessment, EUnetHTA. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2009;25(Suppl 2):1–8.

Kristensen FB, Mäkelä M, Neikter SA, Rehnqvist N, Håheim LL, Mørland B, et al. European network for health technology assessment, EUnetHTA: planning, development, and implementation of a sustainable European network for health technology assessment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2009;25(Suppl 2):107–16.

Jansen E, Hines PA, Berntgen M, Brand A. Strengthening the interface of evidence-based decision making across European regulators and health technology assessment bodies. Value Health. 2022;25(10):1726–35.

Loblova O. Epistemic communities and experts in health policy-making. Eur J Public Health. 2018;28(Suppl_3):7–10.

Luukkainen S. Developing the health promotion knowledge of the municipalities in South-Savo County in Finland. J Nurs Manag. 2006;14(6):490–3.

Stark C, Innes A, Szymczynska P, Forrest L, Proctor K. Dementia knowledge transfer project in a rural area. Rural Remote Health. 2013;13(2):2060.

de Haas B, van der Kwaak A. Exploring linkages between research, policy and practice in the Netherlands: perspectives on sexual and reproductive health and rights knowledge flows. Health Res Policy Syst. 2017;15(1):40.

Perkins BL, Garlick R, Wren J, Smart J, Kennedy J, Stephens P, et al. The Life Science Exchange: a case study of a sectoral and sub-sectoral knowledge exchange programme. Health Res Policy Syst. 2016;14:32.

McAteer J, Di Ruggiero E, Fraser A, Frank JW. Bridging the academic and practice/policy gap in public health: perspectives from Scotland and Canada. J Public Health. 2019;41(3):632–7.

Gombos K, Herczeg R, Eross B, Kovacs SZ, Uzzoli A, Nagy T, et al. Translating scientific knowledge to government decision makers has crucial importance in the management of the COVID-19 pandemic. Popul Health Manag. 2021;24(1):35–45.

Sell K, Saringer-Hamiti L, Geffert K, Strahwald B, Stratil JM, Pfadenhauer LM. [Expert committees in German public health policymaking during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: a document analysis]. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2021.

Hoeijmakers M, Harting J, Jansen M. Academic Collaborative Centre Limburg: a platform for knowledge transfer and exchange in public health policy, research and practice? Health Policy. 2013;111(2):175–83.

Wehrens R. Beyond two communities—from research utilization and knowledge translation to co-production? Public Health. 2014;128(6):545–51.

van der Graaf P, Shucksmith J, Rushmer R, Rhodes A, Welford M. Performing collaborative research: a dramaturgical reflection on an institutional knowledge brokering service in the North East of England. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019;17(1):49.

Spitters H, van de Goor LAM, Lau CJ, Sandu P, Eklund Karlsson L, Jansen J, et al. Learning from games: stakeholders’ experiences involved in local health policy. J Public Health. 2018;40(Suppl_1):i39–49.

Aro AR, Bertram M, Hamalainen RM, Van De Goor I, Skovgaard T, Valente A, et al. Integrating research evidence and physical activity policy making-REPOPA project. Health Promot Int. 2016;31(2):430–9.

Hankivsky O, Vorobyova A, Salnykova A, Rouhani S. The importance of community consultations for generating evidence for health reform in Ukraine. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2017;6(3):135–45.

King G, Farmer J. What older people want: evidence from a study of remote Scottish communities. Rural Remote Health. 2009;9(2):1166.

Weiler R, Neyndorff C. BJSM social media contributes to health policy rethink: a physical activity success story in Hertfordshire. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(9):593.

Payne H. Transferring research from a university to the United Kingdom National Health Service: the implications for impact. Health Res Policy Syst. 2017;15(1):56.

Reynolds J, McGrath M, Halliday E, Ogden M, Hare S, Smolar M, et al. “The opportunity to have their say”? Identifying mechanisms of community engagement in local alcohol decision-making. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;85: 102909.

Martensen H, Diependaele K, Daniels S, Van den Berghe W, Papadimitriou E, Yannis G, et al. The European road safety decision support system on risks and measures. Accid Anal Prev. 2019;125:344–51.

Cresswell K, Callaghan M, Mozaffar H, Sheikh A. NHS Scotland’s Decision Support Platform: a formative qualitative evaluation. BMJ Health Care Informat. 2019;26(1): e100022.

Liu H-Y, Bartonova A, Neofytou P, Yang A, Kobernus MJ, Negrenti E, et al. Facilitating knowledge transfer: decision support tools in environment and health. Environ Health. 2012;11(1):S17.

Deloly C, Gall AR, Moore G, Bretelle L, Milner J, Mohajeri N, et al. Relationship-building around a policy decision-support tool for urban health. Build Cities. 2021;2(1):717–33.

Chung Y, Salvador-Carulla L, Salinas-Pérez JA, Uriarte-Uriarte JJ, Iruin-Sanz A, García-Alonso CR. Use of the self-organising map network (SOMNet) as a decision support system for regional mental health planning. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):35.

McGettigan P, Alonso Olmo C, Plueschke K, Castillon M, NoguerasZondag D, Bahri P, et al. Patient registries: an underused resource for medicines evaluation: operational proposals for increasing the use of patient registries in regulatory assessments. Drug Saf. 2019;42(11):1343–51.

Allen A, Patrick H, Ruof J, Buchberger B, Varela-Lema L, Kirschner J, et al. Development and pilot test of the registry evaluation and quality standards tool: an information technology-based tool to support and review registries. Value in Health. 2022;25(8):1390–8.

Tiessen J, Celia C, Ling T, Ridsdale H, Bareaud M, van Stolk C. Evaluation of DG SANCO data management practices. Rand Health Quarterly. 2011;1(3):11.

World Health Organization. Regional Office for E. Collection and integration of data on refugee and migrant health in the WHO European Region: technical guidance. Copenhagen: World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe; 2020 2020.

Haby MM, Chapman E, Clark R, Barreto J, Reveiz L, Lavis JN. Designing a rapid response program to support evidence-informed decision-making in the Americas region: using the best available evidence and case studies. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):117.

El-Jardali F, Bou-Karroum L, Fadlallah R. Amplifying the role of knowledge translation platforms in the COVID-19 pandemic response. Health Res Policy Syst. 2020;18(1):58.

Pantoja T, Barreto J, Panisset U. Improving public health and health systems through evidence informed policy in the Americas. BMJ. 2018;362: k2469.

Dovlo D, Nabyonga-Orem J, Estrelli Y, Mwisongo A. Policy dialogues—the “bolts and joints” of policy-making: experiences from Cabo Verde, Chad and Mali. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(4):216.

Lavis JN, Boyko JA, Oxman AD, Lewin S, Fretheim A. SUPPORT Tools for evidence-informed health Policymaking (STP) 14: organising and using policy dialogues to support evidence-informed policymaking. Health Res Policy Systems. 2009;7(1):S14.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms. Sabine Salameh for her support in data extraction.

Funding

Open access fees are funded by the European Union. The authors affiliated with the World Health Organization (WHO) are alone responsible for the views expressed in this publication and they do not necessarily represent the decisions or policies of the WHO.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FEJ, TRS and DNO conceptualized the study. LBK designed and run the search strategy. LBK, NHi, MH, NHe, MA, NK, AH screened articles for eligibility and abstracted data from papers. LBK, NHi and MA analyzed the data. FEJ, LBK, TRS and DNO contributed to the interpretation of results and drafted the manuscript. FEJ, NAM, TRS and DNO critically reviewed the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Appendix 1:

List of Member States of the WHO European Region.

Additional file 2: Appendix 2:

Search strategies.

Additional file 3: Appendix 3.

Table of characteristics - Indicators.

Additional file 4: Appendix 4.

Table of characteristics - Surveys.

Additional file 5: Appendix 5.

Table of characteristics - Registries.

Additional file 6: Appendix 6.

Table of characteristics - Surveillance and Observatories.

Additional file 7: Appendix 7.

Table of characteristics - HIS.

Additional file 8: Appendix 8.

Table of characteristics - Evidence Synthesis.

Additional file 9: Appendix 9.

Table of characteristics - Health Reports.

Additional file 10: Appendix 10.

Table of characteristics - Policy dialogues.

Additional file 11: Appendix 11.

Table of characteristics - Evidence networks.

Additional file 12: Appendix 12.

Table of characteristics - Community engagement.

Additional file 13: Appendix 13.

Table of characteristics - Decision Support Tools.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

El-Jardali, F., Bou-Karroum, L., Hilal, N. et al. Knowledge management tools and mechanisms for evidence-informed decision-making in the WHO European Region: a scoping review. Health Res Policy Sys 21, 113 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-023-01058-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-023-01058-7