Abstract

Background

Evidence-based health system guidelines are pivotal tools to help outline the important financial, policy and service components recommended to achieve a sustainable and resilient health system. However, not all guidelines are readily translatable into practice and/or policy without effective and tailored implementation and adaptation techniques. This scoping review mapped the evidence related to the adaptation and implementation of health system guidelines in low- and middle-income countries.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review following the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for scoping reviews. A search strategy was implemented in MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase, CINAHL, LILACS (VHL Regional Portal), and Web of Science databases in late August 2020. We also searched sources of grey literature and reference lists of potentially relevant reviews. All findings were reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews.

Results

A total of 41 studies were included in the final set of papers. Common strategies were identified for adapting and implementing health system guidelines, related barriers and enablers, and indicators of success. The most common types of implementation strategies included education, clinical supervision, training and the formation of advisory groups. A paucity of reported information was also identified related to adaptation initiatives. Barriers to and enablers of implementation and adaptation were reported across studies, including the need for financial sustainability. Common approaches to evaluation were identified and included outcomes of interest at both the patient and health system level.

Conclusions

The findings from this review suggest several themes in the literature and identify a need for future research to strengthen the evidence base for improving the implementation and adaptation of health system guidelines in low- and middle-income countries. The findings can serve as a future resource for researchers seeking to evaluate implementation and adaptation of health system guidelines. Our findings also suggest that more effort may be required across research, policy and practice sectors to support the adaptation and implementation of health system guidelines to local contexts and health system arrangements in low- and middle-income countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Evidence-informed guidelines are pivotal to reforming healthcare and strengthening health systems for healthier communities worldwide [1, 2]. WHO conceptualizes guidelines as a set of evidence-informed recommendations related to practice, public health or policy for informing and assisting decision-makers (e.g. policy-makers, healthcare providers or patients) [3]. In contrast to clinical practice guidelines focused on the appropriateness of clinical care activities, health system guidelines outline the required system, policy and/or finance components recommended to address health challenges [4, 5].

Despite the rigorous systematic synthesis of current research evidence focused on the development of high-quality guidelines, not all guidelines are readily and directly translatable into practice and/or policy [6, 7]. According to Balas and Boren, the small proportion of published evidence (approximately 14%) that does translate into practice can take upwards of 17 years from start to finish [8, 9]. Understanding implementation and adaptation strategies that facilitate the uptake of evidence-informed guidelines and recommendations is an urgent research and policy priority [10,11,12,13]. Implementation strategies are often defined as “methods or techniques used to enhance the adaptation, implementation, and sustainability of a program or practice” [14]. Guideline adaptation strategies involve systematically modifying guidelines developed in a specific environment to be suitable for application in other contextual settings (e.g. organizational or cultural) [15].

A review of WHO guidelines by Wang et al. [16] revealed a lack of implementation strategies that were evidence-based and involved active techniques (e.g. workshops, evaluation surveys, training) within their relevant implementation sections. WHO is currently focused on enhancing the adaptability of guidelines [17] and integrating adaptation strategies into their implementation plans [18]. For successful uptake, even high-quality international guidelines require adapting and tailoring to local contexts or circumstances [19]. To help achieve success, the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research (a WHO-hosted partnership) created the Research to Enhance the Adaptation and Implementation of Health Systems Guidelines (RAISE) portfolio, which aims to support decision-making on policy and systems in six low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [20]. However, much remains to be known about the factors and processes to enhance their adaptation and implementation [16, 20]. Additional evidence is needed to inform good practices, effective methods and evidence-based implementation and adaptation recommendations for the utilization of health system guidelines.

Neglecting to consider the interaction between contextual factors and guideline uptake is likely to lead to underperformance or failure [21,22,23,24,25]. It is important to recognize political, cultural and socioeconomic contexts and how these intersectional factors can influence health system guideline implementation and adaptation processes. Several methods have been derived for the selection and tailoring of implementation strategies to address these contextual needs [26]. Various taxonomies have been established as a means to better describe and categorize implementation strategies [27,28,29,30,31,32,33] and to conceptualize context to allow for the analysis of determinants (e.g. barriers and enablers) of implementation outcomes [34]. Frameworks have also been identified for adapting health-related guidelines, but often lack guidance on implementation [18, 35]. Therefore, the best methods for developing tailored implementation strategies and selecting adaptation frameworks remain to be identified [12, 18].

We conducted a preliminary search of PROSPERO, MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports. No reviews were identified that addressed adapting and implementing health system guidelines in LMICs. The search revealed a related overview of systematic reviews examining the effects of implementation techniques for health system initiatives that were deemed relevant to low-income countries (LICs) [36]. Despite this review and the acknowledged contextual differences between LICs and high-income countries (HICs), the findings were derived primarily from studies conducted in HICs, leaving a significant gap in the literature examining any contextual nuances of implementation and adaptation of health system guidelines specifically in LMICs.

The objective of this scoping review is unique, as it provides an overview of available evidence related to the implementation and adaptation of health system guidelines evaluated in LMICs. A focus on adaptation and implementation processes is a novel contribution in the literature by examining both of their strategies, interactions and influences. Recognizing the intricacy of contextual factors, we will only be examining implementation and adaptation strategies that directly happened in LMICs. We adopted an integrated knowledge translation approach by collaborating with a broad range of key informants, including the lead of each partner country in the WHO RAISE portfolio, throughout the review process to help ensure that the findings were relevant to knowledge users. Integrated knowledge translation is an approach to research where researchers and end-users work collaboratively to identify relevant knowledge gaps and ensure the production of actionable knowledge [37]. The results of this scoping review provide critical insight into the development of evidence-based implementation and adaptation recommendations for health system guidelines in LMICs.

Review aims

This scoping review assessed and mapped the available evidence related to adapting and implementing health system guidelines and recommendations in LMICs. The following research questions guided the review:

-

1.

What are the common strategies and approaches for implementing health system guidelines and recommendations in LMICs?

-

2.

What are the common strategies and approaches for adapting health system guidelines and recommendations in LMICs?

-

3.

What are the commonly reported outcomes or indicators of success in adaptation and/or implementation of health system guidelines and recommendations in LMICs?

-

4.

What are the commonly reported barriers and facilitators with respect to adaptation and/or implementation of health system guidelines and recommendations in LMICs?

Methods

This scoping review was guided by the methodological framework outlined by the JBI [38]. The framework includes six phases: (i) identifying the research question; (ii) searching for studies; (iii) selecting studies; (iv) extracting, charting and appraising data; (v) synthesizing and reporting findings; (vi) consulting with experts and key stakeholders [38].

Inclusion criteria

Population

In alignment with the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) taxonomy of health system interventions [39], this review considered articles including any healthcare organizations, healthcare professionals or healthcare recipients targeted for change by health system guidelines within LMICs.

Concept

The concepts relevant for this review consist of the implementation and adaptation strategies, frameworks, and barriers and/or facilitators related to the adaptation and/or implementation of health system guidelines, policies and/or recommendations. Articles were required to explicitly state their intent to implement and/or adapt any evidence-informed health system guideline to be considered for inclusion. Health systems were conceptualized to encompass any system responsible for the provision of health services, finances, and/or governance [40]. Our review considered any evidence-informed (as reported by author) health system guidelines, regardless of the developer. Articles that described their intent to implement and/or adapt clinical practice guidelines were excluded.

Implementation and adaptation, while often undertaken simultaneously, are two distinct concepts being examined by this review. Implementation strategies were defined as any “methods or techniques used to enhance the adaptation, implementation, and sustainability” [14]. Adaptation strategies were defined as a “process of thoughtful and deliberate alteration to the design or delivery of an intervention, with the goal of improving its fit or effectiveness in a given context” [41]. Articles were required to report on the implementation and/or adaptation of health system guidelines to be considered for inclusion.

Context

Context in this review involved adaptation and/or implementation strategies applied in LMICs at a health system level. LMICs were defined by the World Bank standards based on gross national income for the 2021 fiscal year [42]. Studies or data related to HICs were excluded from this review.

Types of sources

This scoping review considered any quantitative, qualitative or mixed-methods studies that evaluated the implementation and/or adaptation of health system guidelines in any LMICs. Articles that were descriptive in nature (e.g. editorials, commentaries, opinion papers) or did not have evaluation processes for assessing the implementation/adaptation strategy were excluded. Literature reviews that reported on relevant concepts were first reviewed for primary studies and then ultimately excluded. Studies published in English, not restricted by date of publication, were included.

Search strategy

The search strategy aimed to locate both published and unpublished studies. An initial search of MEDLINE (Ovid) was undertaken by a librarian scientist to identify relevant studies of interest. The search strategy was developed using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and keywords contained in the titles and abstracts of relevant articles. A full search strategy for MEDLINE (Ovid) is included in our Additional file 1. This search strategy underwent peer review by another librarian using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) [43] to ensure its accuracy. The search strategy was then adapted for each included information source. Lastly, primary studies from identified literature reviews were scanned for additional studies.

Information sources

We employed our search strategy in MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature; VHL Regional Portal), and Web of Science databases. Sources of grey literature included a search of the CADTH (Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health) Grey Matters Tool, Google, Google Scholar, and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. These databases were chosen to capture potential articles across relevant countries.

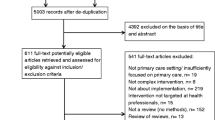

Study selection

Search results were uploaded into Covidence systematic review software [45] for reference management. To ensure that eligibility criteria were uniformly applied by all reviewers, team members independently pilot-tested 20 citations and met to resolve any areas in need of clarification. Two reviewers then independently screened all titles and abstracts for assessment against the inclusion criteria. Full-text articles of potentially relevant studies were retrieved, and two reviewers independently assessed the full-text studies for eligibility. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion at each stage of the study selection process. If consensus could not be achieved, a third reviewer made the final decision. Reasons for exclusion of full-text studies were documented and are reported in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) flow diagram [46].

Data extraction

Data were extracted using a predetermined extraction form to collect key findings relevant to the scoping review questions (Additional file 2). The main concepts in the data extraction form included year of publication, country, study aim(s), study population, setting, funding source, use of theoretical/conceptual frameworks, guideline description, implementation strategies, adaptation strategies, outcomes of interest, study methods, barriers and enablers, key results and stakeholder engagement [38]. Details regarding implementation strategies were extracted based on Proctor and colleagues’ recommendations for operationalizing and reporting implementation techniques [14]. This data extraction framework facilitated the collection of specific and pertinent data related to reported implementation strategies, such as duration, dose and justification. Further, the Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications–Enhanced (FRAME) was used to guide data extraction of adaptation strategies to capture the who, where, when, why and how aspects of modifications [41]. As this review seeks to examine implementation and adaptation as two distinct concepts, data on implementation and adaptation strategies were extracted independently of each other. If articles reported on both implementation and adaptation strategies, concepts related to processes such as barriers, enablers and outcomes were extracted independently. This could only be accomplished if authors explicitly stated which indicators (e.g. barriers, enablers and outcomes) related to which concepts (implementation or adaptation). If this level of detail was not provided, the data were still extracted but we were unable to infer which indicators related to which concepts. Data were also extracted if authors reported using a theoretical/conceptual framework to guide/justify their implementation and/or adaptation techniques. Two reviewers independently extracted details from the included articles, and disagreements were resolved with a third reviewer.

Quality assessment

The quality of included studies was assessed using the JBI’s critical appraisal tools and the mixed-methods appraisal tool [47, 48]. Two reviewers independently completed the quality assessment. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion. The results of this quality assessment were not used to exclude studies from the review but rather to provide greater insight into the current body of literature on this topic.

Data analysis

We began by categorizing each health system guideline based on the six “building blocks” that WHO identifies as core components to strengthening health systems: (1) service delivery, (2) health workforce, (3) health information systems, (4) access to essential medicines, (5) financing and (6) leadership or governance [49]. Health system guidelines were categorized into these building blocks based on their primary aim. Subsequently, directed content analysis was used to map implementation strategies according to the list of 73 implementation strategies and definitions outlined in the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project [28]. The ERIC framework was developed through iterative consultations with experts and literature to derive a comprehensive list of known implementation strategies [28]. Analysis was completed by two reviewers independently, and disagreements were resolved through consensus. Guided by the FRAME, thematic analysis was used to examine and group similarities in adaptation strategies and the who, what, where, why and when of any modification that took place. Lastly, the Capability, Opportunity and Motivation Behaviour (COM-B) model guided the coding of the reported barriers to and enablers of implementation and adaptation [30, 50]. The COM-B model is a theoretically driven, evidence-based framework that outlines a systematic process to identify and understand barriers and enablers with respect to implementation/adaptation of health initiatives [30, 50]. This model also links the identified barriers and enablers to the required mechanisms needed to enact change [51]. Mapping the findings onto published taxonomies, such as the ERIC framework to classify implementation strategies, the FRAME to detail important considerations to adaptation techniques, and the COM-B model to map barriers and enablers, allows for the identification of possible gaps in current knowledge and opportunities for future research [52]. Further, results summaries were stratified per LMIC lending groups (low-, lower-middle and upper-middle-income) and by using WHO’s six building blocks to assess for potential trends [49].

Descriptive summary tables of all included studies were created to outline extracted data specific to the health system guidelines, implementation strategies, adaptation strategies, outcomes/results, and article characteristics. Narrative summaries were included to address each research question.

Results

A total of 8622 unique references were identified from the search strategy. No additional citations were uncovered by searching the reference lists of relevant reviews or grey literature sources. After title and abstract screening, 284 papers remained for full-text review. Following this second stage of review, 41 articles were included for data analysis (see Fig. 1 for Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses [PRISMA] diagram) [53].

Article summary characteristics

Identified articles were published between 2005 and 2010 (n = 6), 2011–2015 (n = 10), and 2016 and beyond (n = 25) (see Fig. 2). Studies were most frequently conducted in upper-middle-income countries (n = 21), followed by lower-middle-income countries (n = 14) and LICs (n = 5) (see Fig. 3). One study reported on case study findings from low-, middle-, and upper-middle-income countries. Twenty-two studies used qualitative methods, 14 studies employed mixed methods, and five used cross-sectional methods to answer their research questions. Sources of funding varied among studies and often included multiple sources (see Fig. 4). Most studies reported funding from an HIC source (n = 21) (e.g. Irish Aid, and United Kingdom’s Wellcome Trust). Other studies reported funding from local country/context initiatives (n = 6) and high-income and local country partnerships (n = 5). The remaining reported that no funding was received (n = 2) or did not report information on funding (n = 7). Healthcare workers and end-users were the most commonly targeted study populations. Settings varied across urban and rural locations and community and hospital sites. Articles reported implementing health system guidelines in urban hospitals (n = 7), both urban and rural communities (n = 7), only urban communities (n = 7), and both urban and rural hospitals (n = 5). Only one article reported on implementation of a guideline in both urban and rural clinics and hospitals. Please refer to Table 1 for a full summary of article characteristics. Any acronyms used in the tables can also be found in Additional file 3.

Health system guidelines

Table 2 summarizes the health system guidelines implemented in the included studies. While specific guidelines varied across studies, out of the total 41 studies, three reported on implementation of the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) guidelines and another three outlined the Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV/AIDS guidelines.

Service delivery was the health system building block most frequently targeted by the identified guidelines (n = 24). The remaining building blocks were targeted as follows, in descending order: health workforce (n = 5), financing (n = 4), access to essential medicine (n = 4), health information system (n = 2), and leadership and governance (n = 2).

Adaptation strategies

Only 14 articles explicitly reported on the concept of adaptation. Rarely did articles specifically comment on the strategies used to determine what and why adaptations were necessary. Those that reported how adaptations occurred often described any modifications as being suggested solutions to identified challenges during both pre- and post-implementation. Three articles also described a dedicated multidisciplinary working group aimed to gather feedback and identify required modifications. Six articles reported adaptations to be reactive in nature and another six reported them to be proactively planned. Modifications made were frequently reported as adding, tailoring or tweaking content elements, such as the addition of training sessions, expanding scope of practices and restructuring funding sources. None of the included articles reported using a guiding framework to help identify areas where adaptation could be beneficial and/or necessary. A full summary of the adaptation strategies and their related concepts according to the FRAME is given in Table 3.

Implementation strategies

Eleven articles included in our review did not provide sufficient detail to adequately discern the strategies used to implement their health system guideline. 38 out of the 72 ERIC-defined implementation strategies were utilized across all 41 studies. A small number of reported implementation strategies were determined by consensus to fall under two separate ERIC categories and were coded as such. Studies reported a range of one to eight strategies to implement their health system initiative, with an average of four distinct implementation strategies. Conducting ongoing training was identified as the most frequent implementation strategy (n = 11), followed by building a coalition (n = 8), use of advisory boards and workgroups (n = 6), conducting educational meetings (n = 6) and developing educational materials (n = 5). The least prevalent ERIC-defined implementation strategies included, but were not limited to, revision of professional roles (n = 2), alterations of incentives/allowance structure (n = 2), assessments for readiness and identification of barriers and facilitators (n = 1), and tailoring of strategies (n = 1). A full breakdown of all 38 implementation strategies and their frequencies can be found in Table 4. None of our included studies explicitly reported the use of a theoretical/conceptual framework to guide their selection of implementation strategies.

Outcomes of interest

Table 5 summarizes the outcomes of interest and key results of included studies. Nineteen articles reported the involvement of key stakeholders in various aspects of their design and implementation processes. Stakeholders varied from frontline healthcare workers to policy-makers, government organizations and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). Outcomes of interest were related primarily to documenting and evaluating the implementation process, as well as the impact of the guideline on the health system (n = 39). These included assessing the barriers to and enablers of implementation, eliciting end-users’ experiences and perspectives, monitoring system and service changes, evaluating resource use, identifying future steps and comparing guideline expectations to real-world impacts. Additionally, one article explicitly specified the documentation of an implementation framework as an outcome of interest. Patient-level outcomes were noted as an indicator of success and included measuring health outcomes and quality of care delivery (n = 3). While many outcomes of interest were indicators of the overall success of the health system guideline integration, there were no outcomes of interest specifically reported as related to adaptations.

Outcome measures

Outcome measures included interviews/focus groups (n = 29), document/policy analysis (n = 10), surveys/questionnaires (n = 9), health administrative data and medical records (n = 8), field visits/observations (n = 4), secondary data from literature/guideline reviews (n = 2), individual case studies (n = 2), clinical assessment tools (n = 1), performance assessment tools (n = 1) and patient observations (n = 1). A full breakdown of outcomes is presented in Table 5.

Barriers and enablers related to implementation

Reported barriers to and enablers of implementation of health system guidelines were coded using the COM-B framework [54]. Barriers and enablers that were most frequently reported by identified studies were associated with physical (n = 36) or social (n = 22) opportunity. Physical opportunities are defined as the environmental context and resources, whereas social opportunities refer to the social influences, such as norms and cultural factors [54]. Financial constraints, access to resources, and training (or lack thereof) were persistent physical opportunity factors described. Language and communication, political instability and power imbalances are all examples of reported barriers or enablers related to social opportunities.

Implementation barriers and enablers related to psychological (n = 15) and physical capabilities (n = 19) were the second most frequently coded category in the COM-B framework. Physical capabilities describe the skills and abilities required, while psychological capabilities refer to the concepts of knowledge, memory, decision-making and behavioural regulation [54]. Identified articles reported barriers and enablers related to the knowledge about implemented guidelines, the emotional toll on frontline workers and the resistance to change. Physical capabilities included adapting training materials specific to the needs of end-users and ongoing training/mentorship with supervision.

Reflective (n = 4) and automatic (n = 10) motivations were the least often coded barrier and enabler in our review. Reflective motivation refers to the roles, identities and beliefs about consequences [54]. Resistance to or acceptance of change, trust in the guidelines, and defining role and responsibility attributes are all examples noted among the reflective motivation category. Automatic motivation refers to the emotion and reinforcement influencing target behaviour [54]. Dedicated commitment, enthusiasm and motivation to implement health system guidelines were reported as a barrier and/or enabler. A summary of the COM-B analysis can be found in Tables 6 and 7. A full breakdown of extracted and analysed data can be found in Additional file 4.

Barriers and enablers related to adaptation

Eight articles reported barriers and enablers related to adaptation of the health system guidelines. Of these, physical opportunities were the most commonly reported barriers and enablers, with articles describing the use of technical working groups to adjust and manage unexpected changes, ensure flexibility in initiatives, and create new structures/systems to facilitate local adaptation (n = 6). Strong multisectoral collaboration, proactive leadership and culturally appropriate support are all examples of barriers and enablers related to social opportunities that were reported (n = 3). Reflective motivation (n = 2) was the only other COM-B category captured in reported barriers and enablers with respect to adaptation by this review. This related to a lack of available evidence influencing choices and end-users valuing additional (and adapted) components to the initiatives.

Quality appraisal

Twenty-seven articles ranked high (67–100%) in their quality assessments. Seven articles ranked medium (33–66%) and seven ranked low (0–32%) (see Table 1). Those with medium- and lower-quality scores often lacked details related to their study methods, resulting in an unclear understanding of the implementation and initiative fidelity. Results from these studies should be considered with this in mind.

Discussion

This scoping review located, mapped and codified published literature exploring the adaptation and implementation of health system guidelines in LMICs to assess trends and identify potential gaps. Through the synthesis of available evidence, we were able to identify common strategies for adapting and implementing health system guidelines, related barriers and enablers, and indicators of success.

Overall, the most common type of implementation strategies used to facilitate the integration of health system guidelines involved education, training, clinical supervision and the formulation of working groups and advisory boards. Examples of education and training include the development of standardized educational materials, as well as national training and feedback sessions (see Table 4 for a breakdown of all examples). While this review can comment on the types of implementation strategies utilized, specific details such as the duration and dose of these techniques were largely underreported by the authors of the included studies (e.g. 1-day vs month-long workshops). The reported educational and collaborative implementation strategies are in direct alignment with current literature and support similar emerging themes in other healthcare and income settings [55, 56]. A recent review of techniques used to implement nursing practice guidelines across different health settings reveals that education-based strategies were almost always incorporated in the implementation plan [55]. Our findings are consistent with other works in LMICs cited in Imamarua et al.’s (2017) literature synthesis of implementation strategies to deliver maternal practice guidelines [56]. While these reviews identified the involvement of local opinion leaders in their implementation tactics, the formal creation of advisory groups (such as developing technical working groups) appears to be more common in health system-based implementation initiatives than in clinical practice guidelines. This could be reflective of the complex nature of health systems, social norms and values in local communities regarding decision-making, and the various actors that need to be thoughtfully and proactively engaged to facilitate implementation. Furthermore, included studies used an average of four implementation strategies, and less than half of potential strategies available to them (38/73 techniques defined by ERIC). Thus, our review highlights the potential need to leverage and combine a wider variety of implementation techniques to address known barriers to changes and to achieve policy/programme goals.

Though most of the included articles detailed rationales for implementing their targeted health system guidelines, the selection of implementation strategies did not appear to be guided by foundational knowledge, theory or conceptual frameworks. Further, only three studies applied a formal implementation plan [57,58,59]. Implementation science literature highlights the critical importance of identifying and tailoring implementation techniques to successfully transition evidence into real-world practice [60, 61]. Conducting behavioural analyses to identify barriers and facilitators can then be used to guide the selection of evidence-based strategies and to mitigate potential challenges while simultaneously amplifying promising facilitators [54, 60, 61]. Differing levels of available human and physical resources, political structures, professional roles and responsibilities, and cultural and religious practices are all salient and intersectional factors that need to be considered within an implementation plan for health system initiatives [62, 63]. These contextual factors are of particular importance to consider in potentially resource-limited settings to optimize strengths and attend to weaknesses [63]. One component necessary for building a resilient health system is an awareness of the current strengths and weaknesses within existing structures to inform practice and policy planning [64]. There are various evidence-based frameworks and taxonomies that provide structured and systematic processes to identify existing barriers and enablers in specific contexts [26, 28, 54, 65]. Existing tools such as the COM-B model can be used to help identify and map known implementation barriers and enablers and assist in selecting targeted techniques to influence change at the health system level [54]. The use of evidenced-based conceptual and theoretical frameworks could help to improve the selection of individualized implementation techniques and ultimately improve the successful integration of health system guidelines in LMICs.

Lack of consistent funding was a noted barrier to the implementation of health system guidelines. Despite this, only a handful of articles reported accessing new funding sources as part of their implementation plan [66,67,68,69]. While seven studies were conducted in an LIC setting, reports of financial constraints were not limited to those within LICs. Our findings suggest that securing implementation research funding is arduous, irrespective of a country’s income level. Recent work from Ritchie et al. [62] explored the challenges experienced among LMICs when translating maternal health evidence into practice and revealed that lack of health system funding was one of the most common barriers to evidence implementation in LMICs. This barrier, however, may not be unique to LMICs, with sustained funding being challenging even among high-income contexts [70]. As highlighted in the implementation science literature, this is of particular importance when considering the ability to sustain the delivery of health system guidelines beyond their initial implementation [71]. Partnering with NGOs was one strategy utilized by some of our included articles to help fund initiatives. However, while initial financial support may provide the necessary seed money and resources to help launch initiatives, projects without sustained sources of funding risk being shut down [70]. It is also noteworthy that over half of the included studies reported funding sources stemming solely from high-income funding initiatives (e.g. Irish Aid, Australian government funding, Canada’s International Development Research Centre), with only 11 studies utilizing funds from their local country (i.e. Brazilian Ministry of Education, China’s Medical Board). Financial commitments and sustained funding from health ministries is essential to supporting implementation efforts and facilitating the longevity and sustainability of moving evidence into practice and strengthening implementation of health system guidelines into the real-world context.

When stratifying our findings by WHO’s health system building blocks, it became clear that change at the health system level is often dependent on addressing all intersecting concepts. For example, a majority of our identified health system guidelines targeted the service delivery building block, and yet their related barriers included lack of financing, resources and/or leadership and government commitment. Guidelines that targeted the health workforce building block reported barriers specific to the lack of knowledge about the guidelines, human resources and funding. These findings highlight the intersectional nature of all health system building blocks and the critical need to look across components to facilitate successful system-level change. When exploring Rwanda’s great success in improving health outcomes, Sayinzoga and Bijlmakers [72] discovered that one of the key factors influencing their successes was the recognition of the need for multiple and interconnected health system initiatives to achieve set goals. Without accounting for this intersectional nature, initiatives are unlikely to be successful, resulting in wasted time and efforts [63]. Strengthening health systems requires purposeful planning and action across building blocks to enact reform across all health, social and political structures [73, 74]. Researchers and decision-makers are encouraged to incorporate WHO’s health system building blocks as a framework to identify essential elements that may require additional support during the implementation and adaptation of health system guidelines.

Our review revealed a dearth of reported information related to the adaptation of health system guidelines in comparison to implementation strategies. We could find only one study that reported having tailored its guidelines to the needs of the local context as an implementation strategy [75], and only 14 studies reported adaptation techniques. Adapting both health system and clinical practice guidelines is critical to enhancing applicability to the specific setting and to account for differing cultural, organizational and environmental factors [76]. Adaptation of these initiatives can lead to increased local uptake by engaging stakeholders and end-users throughout the process [76]. However, this customization must be carried out carefully to ensure the correct application of evidence and recommendations. Utilizing evidence-based adaptation frameworks provides systematic guidance to ensure that the required modifications are made while still honouring the authenticity of the guideline [76]. Unfortunately, the use of adaptation frameworks was not reported in any of our included articles. While some articles reported on their adaptation techniques, such as Halpern et al.’s [77] detailed description of the creation of a technical working group to adapt each guideline component, most articles did not provide sufficient detail of their processes or reasoning. Rigorous research is needed to explore and identify the most effective adaptation strategies to enhance a guideline’s applicability and uptake at the health system level and support the use of these strategies in practice.

The most frequent indicators of success when implementing and adapting health system guidelines were related to assessing contextualized barriers and facilitators, end-user experiences, and monitoring system changes. Choosing outcomes and indicators is still a debated topic within implementation science literature [8]. As this review identified, many distinguish implementation success by evaluating the process itself (i.e. challenges and successes). Limited studies reported on cost as a critical implementation outcome. Without evaluating implementation cost, sustainability of the health system change is difficult to discern. Conducting cost–benefit analyses and verifying areas of potential cost savings could provide decision-makers with further evidence to support the granting of sustainable funding for implementation of health system guidelines—a major barrier identified in this review.

An alternative ideology asserts success as being related to a health system guideline’s ability to achieve its recommended target and improve care [78]. Only a small proportion of studies included in our review compared guideline targets with real-world changes or leveraged patient-level outcomes to identify improvements in quality of life and health outcomes [75, 79]. The integration of patient- and population-level outcomes may be an important component in the evaluation of health system guidelines in LMICs, as an ultimate goal of a resilient and sustainable health system is to better serve patients and families. There are also a variety of evaluation frameworks that can help guide researchers in the selection of outcomes and indicators of success at the health system level [49]. While flexibility is necessary in evaluation plans, utilizing these frameworks can provide structure and evidence-based processes to ensure comparable outcomes are being selected and reported. This would allow for the streamlined comparison and shared learning across LMICs and could facilitate a more transparent understanding of key factors that drive successful implementation of health system guidelines.

The findings from our quality appraisal and the lack of detail that we were able to extract related to certain concepts (i.e. adaptation strategies) highlight the need to improve adherence to reporting guidelines within this body of literature. By following reporting guidelines in the dissemination of study findings, we can help increase the transparency and completeness of research initiatives [80], ensuring that articles contain the important components and active ingredients for their implementation and adaptation strategies, evaluation methods and health system initiatives. Without this information, it is difficult for readers to discern how implementation and adaptation plans were developed, the techniques employed, and the trustworthiness of findings [81].

Limitations

It is important to consider our findings considering potential limitations. First, our search strategy was limited to reports published in English. We consulted with our knowledge users, who advised that they did not believe this would influence our review findings; however, we acknowledge that not all initiatives conducted in LMICs are reported in this language. This may also partly explain our finding that most initiatives were funded by HICs. Second, given the variation in how authors describe health system guidelines (e.g. recommendations, policies), we may not have captured all potentially relevant studies. Further, it is worth noting that authors may not uniformly use the term “adaptation” when referring to the concept definition adopted in this work. Variations in terminology could have impacted our identification and/or extraction of data. However, our search strategy was carefully developed by an experienced library scientist to mitigate such challenges and comprehensively capture pertinent studies.

Conclusions

Identifying evidenced-based strategies to successfully move evidence into practice continues to be a growing and critical area of research. Health system guidelines are pivotal tools to optimize, strengthen and develop resilient healthcare infrastructures and provisions. This scoping review provides a comprehensive overview of published literature examining the adaptation and implementation of health system guidelines in LMICs. Our findings revealed the most common strategies for implementing health system guidelines in LMICs, including education, training, clinical supervision and formation of advisory groups. There is a need to explore the impact of leveraging and combining a wider variety of implementation techniques to achieve policy/programme goals. The reporting of adaptation strategies was an evident gap in this body of literature, highlighting the need for more primary research aimed at identifying effective adaptation techniques to enhance a guideline’s applicability and uptake at the health system level. Given the lack of theoretical frameworks identified in included studies, research teams can turn to established implementation and adaptation frameworks as a starting point to help guide their work. Furthermore, while the absence of sustained funding and financial commitments was identified as a salient barrier to the implementation of health system guidelines, there was a lack of studies reporting cost as an evaluation outcome. Future researchers are encouraged to consider conducting cost analyses to create a case for decision-makers to support the granting of sustainable funding for health system guidelines. Our findings suggest that more effort may be required across research, policy and practice sectors to support the adaptation and implementation of health system guidelines to local contexts and health system arrangements in LMICs.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.

Abbreviations

- LMICs:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- LIC:

-

Low-income country

- HIC:

-

High-income country

- EPOC:

-

Effective Practice and Organisation of Care

- COM-B:

-

Capability, Opportunity and Motivation Behaviour model

- RAISE:

-

Research to Enhance the Adaptation and Implementation of Health Systems Guidelines

References

Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, Jordan K, Leslie HH, Roder-DeWan S, et al. High-quality health systems in the sustainable development goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(11):e1196–252.

Moberg J, Oxman AD, Rosenbaum S, Schünemann HJ, Guyatt G, Flottorp S, et al. The GRADE evidence to decision (EtD) framework for health system and public health decisions. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):45.

World Health Organization. WHO handbook for guideline development. 2nd ed. Geneva: WHO Press; 2014.

Brouwers MC, Lavis JN, Spithoff K, Vukmirovic M, Florez ID, Velez M, et al. Assessment of health systems guidance using the appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation-health systems (AGREE-HS) instrument. Health Policy. 2019;123(7):646–51.

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Clinical practice guidelines clinical practice guidelines. 2021. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/providers/clinicalpractice. Accessed 23 Nov 2021.

McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, DeCristofaro A, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635–45.

Sheldon TA, Cullum N, Dawson D, Lankshear A, Lowson K, Watt I, et al. What’s the evidence that NICE guidance has been implemented? Results from a national evaluation using time series analysis, audit of patients’ notes, and interviews. BMJ. 2004;329(7473):999.

Westfall JM, Mold J, Fagnan L. Practice-based research—“Blue Highways” on the NIH roadmap. JAMA. 2007;297(4):403–6.

Balas AE, Boren SA. Managing clinical knowledge for health care improvement. In: Bemmel J, McCray A, editors. Yearbook of medical informatics 2000: patient-centered systems. Stuttgart: Schattauer Verlagsgesellschaft mbH; 2000. p. 65–70. http://hdl.handle.net/10675.2/617990.

Institute of Medicine. Initial national priorities for comparative effectiveness research: health and medicine division. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009. http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/reports/2009/comparativeeffectivenessresearchpriorities.aspx. Accessed 14 Dec 2019.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). PA-18-793: AHRQ health services research demonstration and dissemination grants (R18). https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/pa-18-793.html. Accessed 14 Dec 2019.

Powell BJ, Fernandez ME, Williams NJ, Aarons GA, Beidas RS, Lewis CC, et al. Enhancing the impact of implementation strategies in healthcare: a research agenda. Front Public Health. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00003.

Glandon D, Meghani A, Jessani N, Qiu M, Bennett S. Identifying health policy and systems research priorities on multisectoral collaboration for health in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(Suppl 4): e000970.

Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013;8:139.

Guidelines International Network. Working groups/adaptation. 2019. https://g-i-n.net/working-groups/adaptation. Accessed 14 Dec 2019.

Wang Z, Norris SL, Bero L. Implementation plans included in World Health Organisation guidelines. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):76.

Dedios MC, Esperato A, De-Regil LM, Peña-Rosas JP, Norris SL. Improving the adaptability of WHO evidence-informed guidelines for nutrition actions: results of a mixed methods evaluation. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):39.

Wang Z, Norris SL, Bero L. The advantages and limitations of guideline adaptation frameworks. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):72.

Schünemann HJ, Fretheim A, Oxman AD. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 13. Applicability, transferability and adaptation. Health Res Policy Syst. 2006;4(1):25.

World Health Organization. Request for proposals: technical support centre—research to enhance the adaptation and implementation of health systems guidelines (RAISE). 2019. https://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/callsforproposals/alliance-rfp-tsc-RAISE.pdf?ua=1.

McCormack B, Kitson A, Harvey G, Rycroft-Malone J, Titchen A, Seers K. Getting evidence into practice: the meaning of “context.” J Adv Nurs. 2002;38(1):94–104.

Kaplan HC, Brady PW, Dritz MC, Hooper DK, Linam WM, Froehle CM, et al. The influence of context on quality improvement success in health care: a systematic review of the literature. Milbank Q. 2010;88(4):500–59.

Taylor SL, Dy S, Foy R, Hempel S, McDonald KM, Ovretveit J, et al. What context features might be important determinants of the effectiveness of patient safety practice interventions? BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(7):611–7.

Tomoaia-Cotisel A, Scammon DL, Waitzman NJ, Cronholm PF, Halladay JR, Driscoll DL, et al. Context matters: the experience of 14 research teams in systematically reporting contextual factors important for practice change. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(Suppl 1):S115–23.

Edwards N, Barker PM. The importance of context in implementation research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67(Suppl 2):S157–62.

Powell BJ, Beidas RS, Lewis CC, Aarons GA, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, et al. Methods to improve the selection and tailoring of implementation strategies. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2017;44(2):177–94.

Powell BJ, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, Carpenter CR, Griffey RT, Bunger AC, et al. A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Med Care Res Rev. 2012;69(2):123–57.

Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21.

Mazza D, Bairstow P, Buchan H, Chakraborty SP, Van Hecke O, Grech C, et al. Refining a taxonomy for guideline implementation: results of an exercise in abstract classification. Implement Sci. 2013;8:32.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95.

Kok G, Gottlieb NH, Peters GJY, Mullen PD, Parcel GS, Ruiter RAC, et al. A taxonomy of behaviour change methods: an intervention mapping approach. Health Psychol Rev. 2016;10(3):297–312.

Alvarez E, Lavis JN, Brouwers M, Carmona Clavijo G, Sewankambo N, Solari L, et al. Developing evidence briefs for policy: a qualitative case study comparing the process of using a guidance-contextualization workbook in Peru and Uganda. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019;17(1):89.

Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Review Group. Data collection checklist. 2002. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18624603.

Nilsen P, Bernhardsson S. Context matters in implementation science: a scoping review of determinant frameworks that describe contextual determinants for implementation outcomes. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):189.

Darzi A, Abou-Jaoude EA, Agarwal A, Lakis C, Wiercioch W, Santesso N, et al. A methodological survey identified eight proposed frameworks for the adaptation of health related guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;86:3–10.

Pantoja T, Opiyo N, Lewin S, Paulsen E, Ciapponi A, Wiysonge CS, et al. Implementation strategies for health systems in low-income countries: an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;12(9):CD011086.

Kothari A, McCutcheon C, Graham ID. Defining integrated knowledge translation and moving forward: a response to recent commentaries. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2017;6(5):299–300.

Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Soares C, Khalil H, Park P. Methodology for JBI scoping reviews. In: The Joanna Briggs institute reviewers’ manual. Adelaide: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2015. p. 1–24.

Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). The EPOC taxonomy of health systems interventions. EPOC resources for review authors. Oslo: Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services. 2016. https://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-taxonomy. Accessed 14 Dec 2019.

World Health Organization. WHO | health systems strengthening glossary. WHO. World Health Organization; 2011. https://www.who.int/healthsystems/hss_glossary/en/index5.html. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

Wiltsey Stirman S, Baumann AA, Miller CJ. The FRAME: an expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):58.

The World Bank. World Bank country and lending groups. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed 14 Feb 2020.

Sampson M, McGowan J, Cogo E, Grimshaw J, Moher D, Lefebvre C. An evidence-based practice guideline for the peer review of electronic search strategies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(9):944–52.

EndNote. EndNote | clarivate analytics . EndNote. n.d. https://endnote.com/. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

Covidence Systematic Review Software. Covidence systematic review software. Covidence. 2018. https://www.covidence.org/.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Critical Appraisal Tools—JBI. http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html. Accessed 22 Dec 2017.

Hong QN, Pluye P, Fabregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, et al. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018: user guide . 2018. https://files.zotero.net/eyJleHBpcmVzIjoxNTkwMTk1OTEzLCJoYXNoIjoiY2NlNDAxYjE4ZDRjYmQyZGJmZmVhZDA2NzkzN2I1NmYiLCJjb250ZW50VHlwZSI6ImFwcGxpY2F0aW9uXC9wZGYiLCJjaGFyc2V0IjoiIiwiZmlsZW5hbWUiOiJNTUFUXzIwMThfY3JpdGVyaWEtbWFudWFsXzIwMTgtMDgtMDFfRU5HLnBkZiJ9/f932095093a0e05566f096b08349aed6adf9e1762c9a32b5d3f87b4882aef83c/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf.

World Health Organization. Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. 2010. https://www.who.int/healthinfo/systems/WHO_MBHSS_2010_full_web.pdf.

What is NVivo? | QSR international. http://www.qsrinternational.com/what-is-nvivo. Accessed 11 Sep 2017.

Michie S, Ashford S, Sniehotta FF, Dombrowski SU, Bishop A, French DP. A refined taxonomy of behaviour change techniques to help people change their physical activity and healthy eating behaviours: the CALO-RE taxonomy. Psychol Health. 2011;26(11):1479–98.

Gagliardi AR, Alhabib S, the members of the Guidelines International Network Implementation Working Group. Trends in guideline implementation: a scoping systematic review. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):54.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Internal Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a guide to designing interventions. 1st ed. Great Britain: Silverback Publishing; 2014.

Spoon D, Rietbergen T, Huis A, Heinen M, van Dijk M, van Bodegom-Vos L, et al. Implementation strategies used to implement nursing guidelines in daily practice: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;111: 103748.

Imamura M, Kanguru L, Penfold S, Stokes T, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Shaw B, et al. A systematic review of implementation strategies to deliver guidelines on obstetric care practice in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;136(1):19–28.

Kihembo C, Masiira B, Nakiire L, Katushabe E, Natseri N, Nabukenya I, et al. The design and implementation of the re-vitalised integrated disease surveillance and response (IDSR) in Uganda, 2013–2016. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):879.

Bryce J, Victora CG, Habicht J-P, Black RE, Scherpbier RW. Programmatic pathways to child survival: results of a multi-country evaluation of integrated management of childhood illness. Health Policy Plan. 2005;20(suppl_1):i5-17.

Moshiri E, Arab M, Khosravi A. Using an analytical framework to explain the formation of primary health care in rural Iran in the 1980s. Arch Iran Med. 2016;19(1):16–22.

Straus S, Tetroe J, Graham I. Knowledge translation in health care: moving from evidence to practice. 2nd ed. Oxford: Wiley; 2013.

Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Fernandez ME, Abadie B, Damschroder L. Choosing implementation strategies to address contextual barriers: diversity in recommendations and future directions. Implement Sci. 2019;14(42):1–15.

Ritchie LM, Khan S, Moore JE, Timmings C, van Lettow M, Vogel JP, et al. Low- and middle-income countries face many common barriers to implementation of maternal health evidence products. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;1(76):229–37.

van Olmen J, Marchal B, Van Damme W, Kegels G, Hill PS. Health systems frameworks in their political context: framing divergent agendas. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):774.

Kruk ME, Myers M, Varpilah ST, Dahn BT. What is a resilient health system? Lessons from Ebola. Lancet. 2015;385(9980):1910–2.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50.

Roman E, Wallon M, Brieger W, Dickerson A, Rawlins B, Agarwal K. Moving malaria in pregnancy programs from neglect to priority: experience from Malawi, Senegal, and Zambia. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2014;2(1):55–71.

Zhou W, Yu Y, Zhao X, Xiao S, Chen L. Evaluating China’s mental health policy on local-level promotion and implementation: a case study of Liuyang Municipality. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):24.

Rahman M, Delarosa J, Luies SK, Alom KR, Quintanar-Solares M, Jabeen I, et al. Understanding key drivers and barriers to implementation of the WHO recommendations for the case management of childhood pneumonia and possible serious bacterial infection with amoxicillin dispersible tablets (DT) in Bangladesh: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):142.

Miguel-Esponda G, Bohm-Levine N, Rodríguez-Cuevas FG, Cohen A, Kakuma R. Implementation process and outcomes of a mental health programme integrated in primary care clinics in rural Mexico: a mixed-methods study. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2020;14(1):21.

Bégin HM, Eggertson L, Macdonald N. A country of perpetual pilot projects. CMAJ. 2009;180(12):1185–1185.

Proctor E, Luke D, Calhoun A, McMillen C, Brownson R, McCrary S, et al. Sustainability of evidence-based healthcare: research agenda, methodological advances, and infrastructure support. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):88.

Sayinzoga F, Bijlmakers L. Drivers of improved health sector performance in Rwanda: a qualitative view from within. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(123):1–10.

Kutzin J, Sparkes SP. Health systems strengthening, universal health coverage, health security and resilience. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(1):2.

Taghreed A. Advancing the application of systems thinking in health. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014;12(50):1–5.

Andrade MV, Noronha K, Cardoso CS, Oliveira CDL, Calazans JA, Souza MN. Challenges and lessons from a primary care intervention in a Brazilian municipality. Rev Saúde Pública. 2019;53:45.

Harrison MB, Legare F, Graham ID, Fervers B. Adapting clinical practice guidelines to local context and assessing barriers to their use. Can Med Assoc J. 2010;182(2):E78–84.

Halpern M, Lachmansingh B, Minior T, Hasbrouck LM, Persaud N, Foo A. Implementation of a standardized HIV patient monitoring system in Guyana. Rev Panam Salud Pública. 2010;28(2):107–13.

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76.

Bergerot CD, Zayat CG, de Azevedo IM, Okuma GY, Pedras RN, Manhães MFM, et al. Implementation of a psycho-oncology program according to international recommendations applied in a Brazilian Public Service. Estud Psicol. 2017;22(4):350–7.

Marušić A, Campbell H. Reporting guidelines in global health research. J Glob Health. 2016;6(2): 020101.

Simera I, Moher D, Hirst A, Hoey J, Schulz KF, Altman DG. Transparent and accurate reporting increases reliability, utility, and impact of your research: reporting guidelines and the EQUATOR Network. BMC Med. 2010;8:24.

Amaral J, Victora C, Leite AJ, Da Cunha A. Implementation of the integrated management of childhood illnesses strategy in Northeastern Brazil. Rev Saúde Pública. 2008;42:598–606.

Leethongdee S. Health sector reform in Thailand: Policy implementation in three provinces. Swansea University; 2007.

Blanco-Mancilla G. Implementation of health policies in Mexico City: What factors contribute to more effective service delivery? London, UK: Department of Social Policy of London School of Economics; 2011.

Zakumumpa H, Dube N, Damian RS, Rutebemberwa E. Understanding the dynamic interactions driving the sustainability of ART scale-up implementation in Uganda. Glob Health Res Policy. 2018;3:23.

Callaghan-Koru JA, Islam M, Khan M, Sowe A, Islam J, Mannan II, et al. Factors that influence the scale up of new interventions in low-income settings: a qualitative case study of the introduction of chlorhexidine cleansing of the umbilical cord in Bangladesh. Health Policy Plan. 2020;35(4):440–51.

Mutabazi JC, Gray C, Muhwava L, Trottier H, Ware LJ, Norris S, et al. Integrating the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV into primary healthcare services after AIDS denialism in South Africa: perspectives of experts and health care workers - a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:582.

Saddi F da C, Harris MJ, Coelho GA, Pêgo RA, Parreira F, Pereira W, et al. Perceptions and evaluations of front-line health workers regarding the Brazilian National Program for Improving Access and Quality to Primary Care (PMAQ): a mixed-method approach. Cad Saúde Pública. 2018;34. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/j/csp/a/YpYHfZJzFGjcs8YqH6pt8NB/?lang=en.

Xia J, Rutherford S, Ma Y, Wu L, Gao S, Chen T, et al. Obstacles to the coordination of delivering integrated prenatal HIV, syphilis and hepatitis B testing services in Guangdong: using a needs assessment approach. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):1–9.

Armstrong CE, Lange IL, Magoma M, Ferla C, Filippi V, Ronsmans C. Strengths and weaknesses in the implementation of maternal and perinatal death reviews in Tanzania: perceptions, processes and practice. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19(9):1087–95.

Ditlopo P, Blaauw D, Bidwell P, Thomas S. Analyzing the implementation of the rural allowance in hospitals in North West Province, South Africa. J Public Health Policy. 2011;32(1):S80-93.

Doherty T, Besada D, Goga A, Daviaud E, Rohde S, Raphaely N. “If donors woke up tomorrow and said we can’t fund you, what would we do?” A health system dynamics analysis of implementation of PMTCT option B+ in Uganda. Glob Health. 2017;13(1):51.

Lovero KL, Lammie SL, van Zyl A, Paul SN, Ngwepe P, Mootz JJ, et al. Mixed-methods evaluation of mental healthcare integration into tuberculosis and maternal-child healthcare services of four South African districts. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1–12.

Mkoka DA, Kiwara A, Goicolea I, Hurtig AK. Governing the implementation of Emergency Obstetric Care: experiences of Rural District Health Managers, Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:333.

Moshiri E, Rashidian A, Arab M, Khosravi A. Analyzing the implementation of the rural allowance in hospitals in North West Province, South Africa. 2016;19(1):2–8.

Muthathi IS, Rispel LC. Policy context, coherence and disjuncture in the implementation of the Ideal Clinic Realisation and Maintenance programme in the Gauteng and Mpumalanga provinces of South Africa. Health Res Policy Syst. 2020;18(1):55.

Schneider H, Nxumalo N. Leadership and governance of community health worker programmes at scale: a cross case analysis of provincial implementation in South Africa. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):72.

Sheikh K, Porter J. Discursive gaps in the implementation of public health policy guidelines in India: the case of HIV testing. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(11):2005–13.

Shelley KD, Belete YW, Phiri SC, Musonda M, Kawesha EC, Muleya EM, et al. Implementation of the community health assistant (CHA) cadre in Zambia: a process evaluation to guide future scale-up decisions. J Community Health. 2016;41(2):398–408.

Carneiro VB, Maia CRM, Ramos EMLS, Castelo-Branco S. Tecobé in Marajó: trend of indicators for the monitoring of primary care before and during the More Physicians for Brazil Program. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2018;23:2413–22.

Costa FF, Calvo MCM. Evaluation of the family health strategy implementation in Santa Catarina in 2004 and 2008. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2014;17:557–70.

Sami S, Amsalu R, Dimiti A, Jackson D, Kenyi S, Meyers J, et al. Understanding health systems to improve community and facility level newborn care among displaced populations in South Sudan: a mixed methods case study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):325.

Febir LG, Baiden FE, Agula J, Delimini RK, Akpalu B, Tivura M, et al. Implementation of the integrated management of childhood illness with parasitological diagnosis of malaria in rural Ghana: health worker perceptions. Malar J. 2015;14(1):174.

Pyone T, Smith H, van den Broek N. Implementation of the free maternity services policy and its implications for health system governance in Kenya. BMJ Glob Health. 2017;2(4):e000249.

Rahman M, Delarosa J, Luies SK, Alom KR, Quintanar-Solares M, Jabeen I, et al. Understanding key drivers and barriers to implementation of the WHO recommendations for the case management of childhood pneumonia and possible serious bacterial infection with amoxicillin dispersible tablets (DT) in Bangladesh: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1–12.

Stein J, Lewin S, Fairall L, Mayers P, English R, Bheekie A, et al. Building capacity for antiretroviral delivery in South Africa: A qualitative evaluation of the PALSA PLUS nurse training programme. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008.

Ejeta LT, Leta Y, Abuye M, Yasin C, Tebekaw Y, Giday T, et al. Implementing the Urban Community Health Information System in Ethiopia: Lessons from the pilot-tests in Addis Ababa, Bishoftu and Hawassa. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2020. Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ejhd/article/view/198793.

Smith Gueye C, Newby G, Tulloch J, Slutsker L, Tanner M, Gosling RD. The central role of national programme management for the achievement of malaria elimination: a cross case-study analysis of nine malaria programmes. Malar J. 2016;15(1):488.

Ryan GK, Nwefoh E, Aguocha C, Ode PO, Okpoju SO, Ocheche P, et al. Partnership for the implementation of mental health policy in Nigeria: a case study of the Comprehensive Community Mental Health Programme in Benue State. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2020;14(1):10.

Investigators of WHO LBW Feeding Study Group D India. World Health Organization Guidelines for feeding low birth weight infants: effects of implementation in first referral level health facilities in India. Indian J Pediatr. 2016;83(6):522–8.

Lavôr DC, Pinheiro JD, Gonçalves MJ. Evaluation of the implementation of the directly observed treatment strategy for tuberculosis in a large city. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2016;50:247–54.

Li Z, Shu D, Xia M, Gao D, Lu D, Huang N, et al. The assessment on impact of essential drugs policy on primary health care system in rural areas of Shandong Province policy and regulation division of the Health Department of Shandong Province. Technol Health Care. 2015;23(s1):S169-76.

Wingfield T, Boccia D, Tovar MA, Huff D, Montoya R, Lewis JJ, et al. Designing and implementing a socioeconomic intervention to enhance TB control: operational evidence from the CRESIPT project in Peru. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):810.

Kavle JA, Ahoya B, Kiige L, Mwando R, Olwenyi F. From national guidelines to implementation: opportunities and challenges for scale-up of baby-friendly community initiative (BFCI) in Kenya. In Breastfeeding Medicine; 2018. p. A-26.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and thank those who helped us during the citation screening and/or data extraction phases: Benjamin Rose-Davis, Kiyana Kamali, Zohra Khatoon, and Daniel Crowther.

Funding

This work was jointly funded by the SPOR Evidence Alliance (Award Number: 201705GSR-386588-GSR-CEAJ-157857) and WHO Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB performed citation screening, data extraction and data analysis, and wrote the initial draft of this manuscript. JAC directly supervised all phases of the work, provided substantial content expertise, contributed to data interpretation, and provided substantial revisions on the initial and final manuscript. RM supervised all phases of the work, provided substantial content expertise, contributed to data interpretation, and provided substantial revisions on the initial and final manuscript. KM and CJ performed citation screening, data extraction, data analysis and provided significant revisions to the manuscript. HW helped draft the initial protocol for this work, performed citation screening, and provided significant revisions to the manuscript. LW, CC, MR and LK-B provided methodological expertise during all phases of the work and provided significant revisions to the manuscript. EV, MV, SJ, LA, SA and DP provided methodological expertise, provided key stakeholder and content expertise to ensure the relevancy of this work, and provided significant revisions to the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No ethical approval was required, as this work is a secondary analysis of published literature.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Search strategy.

Additional file 2.

Data extraction form.

Additional file 3.

Acronyms.

Additional file 4.

Barriers to and enablers of implementation categorized by the COM-B framework (opportunities category).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Breneol, S., Curran, J.A., Marten, R. et al. Strategies to adapt and implement health system guidelines and recommendations: a scoping review. Health Res Policy Sys 20, 64 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-022-00865-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-022-00865-8