Abstract

Background

This study is to identify, summarise and synthesise literature on the causes of the evidence to practice gap for complex interventions in primary care.

Design

This study is a systematic review of reviews.

Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane Library and PsychINFO were searched, from inception to December 2013. Eligible reviews addressed causes of the evidence to practice gap in primary care in developed countries. Data from included reviews were extracted and synthesised using guidelines for meta-synthesis.

Results

Seventy reviews fulfilled the inclusion criteria and encompassed a wide range of topics, e.g. guideline implementation, integration of new roles, technology implementation, public health and preventative medicine. None of the included papers used the term “cause” or stated an intention to investigate causes at all. A descriptive approach was often used, and the included papers expressed “causes” in terms of “barriers and facilitators” to implementation. We developed a four-level framework covering external context, organisation, professionals and intervention. External contextual factors included policies, incentivisation structures, dominant paradigms, stakeholders’ buy-in, infrastructure and advances in technology. Organisation-related factors included culture, available resources, integration with existing processes, relationships, skill mix and staff involvement. At the level of individual professionals, professional role, underlying philosophy of care and competencies were important. Characteristics of the intervention that impacted on implementation included evidence of benefit, ease of use and adaptability to local circumstances. We postulate that the “fit” between the intervention and the context is critical in determining the success of implementation.

Conclusions

This comprehensive review of reviews summarises current knowledge on the barriers and facilitators to implementation of diverse complex interventions in primary care. To maximise the uptake of complex interventions in primary care, health care professionals and commissioning organisations should consider the range of contextual factors, remaining aware of the dynamic nature of context. Future studies should place an emphasis on describing context and articulating the relationships between the factors identified here.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42014009410

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Internationally, the pace of change in health care continues to be rapid with a drive to implement more clinically and cost-effective interventions. Policy makers globally recognise the need to speed up the pace and scale of change. In England, the “Innovation Health and Wealth: Accelerating Adoption and Diffusion in the NHS” report published in 2011 set out to support the adoption and diffusion of innovation across the National Health Service (NHS) [1], since reinforced in the 2014 Five Year Forward View [2].

The drive to improve quality of care while reducing costs has led to widespread attempts to promote evidence-based care. There is clearly a room for improvement: a systematic review including 29 guidelines recommendations from 11 studies shows that only one third of the research evidence informing guidelines is being routinely adhered to [3]. Adherence rates vary from just above 20 to over 80 % [3]. Similar findings have been reported across a number of clinical areas in different countries [4–6]. This delay in translation of evidence-based interventions into every day clinical practice is known as the “evidence to practice gap” or “second translational gap” [7].

In the UK, 90 % of health care encounters take place in primary care [8], and in England, primary care has been subject to particularly rapid changes since the Health and Social Care Act of 2012 [9]. Primary care has its own distinctive research and implementation culture, which has been described as contributing to the evidence to practice gap [10]. Primary care organisations vary in characteristics such as team composition, organisational structures, cultures and working practices; and these diverse contexts can make it challenging to implement change. Almost all changes to practice in primary care involve “complex interventions”, i.e. interventions with multiple interconnecting components [11], and complex interventions can be particularly hard to implement, as they are likely to require change at multiple levels.

A “meta-review” or systematic review of reviews was judged to be the most appropriate method to address this complex area as there is a vast literature which is highly heterogeneous [12, 13]. Existing reviews tend to focus either on a particular type of complex intervention (e.g. introduction of new technologies [14] or promoting uptake and use of guidelines [15]) or on a particular health condition (e.g. mental health [16] or diabetes [17]). Conducting a systematic review of reviews enables the findings of individual reviews to be brought together, compared and contrasted, with the aim of providing a single comprehensive overview, which can serve as a simple introduction to the challenges of achieving change and implementing complex interventions in primary care for managers, clinicians or policy makers.

In this review of reviews, we aim to identify, summarise and synthesise the available review literature on causes of the evidence to practice gap, referred to as any given explanation(s) of why and how complex interventions fail to be implemented in clinical practice, in the primary care setting.

Methods

Search strategy

A comprehensive search was carried out in five electronic databases (including MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and PsychINFO) to seek all potentially eligible papers. The search was performed by the primary reviewer (RL), supported by a specialist librarian (RP). The search strategy was developed using both medical subject headings (MeSH), for example: “translational medical research”, “evidence-based practice”, “general practice”, “review”, “review literature as topic” and free-text words, for example, evidence to practice, evidence-practice gap, family doctor, implementation, adoption and barriers. Articles reported in English and published up to December 2013 were eligible for inclusion in this review. Citation searches were carried out in ISI Web of Science and reference lists of all included articles were screened for additional literature. Details of the search strategy for MEDLINE (Ovid) are provided in Additional file 1.

Eligibility criteria

Eligibility criteria were defined to enable transparent and reproducible selection of papers for inclusion. The following a priori definitions were applied:

Primary Care in developed countries: the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) has defined primary care as “the first level contact with people taking action to improve health in a community” [18]. Primary care teams are defined as teams or groups of health professionals that include a primary care physician (i.e. general practitioners, family physicians, nurse practitioners and other generalist physicians working in primary care settings). Developed countries are often referred to as more economically developed countries, and a list of high-income member countries has been provided by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) [19]. We included reviews with at least 50 % original studies from “primary care” in developed countries. Reviews exclusively on dental practices, pharmacies or developing countries were excluded.

Complex interventions: defined as interventions with several interconnecting components that operate at multiple levels [11].

Implementation: defined as all activities that occur between making an adoption commitment and the time that an innovation becomes part of the organisational routine, ceases to be new or is abandoned [20].

Review: any type of review that provided a description of methods (e.g. identification of relevant studies, synthesis), such as systematic reviews (structured search of bibliographic and other databases to identify relevant literature; use of transparent methodological criteria; presentation of rigorous conclusions about outcomes), narrative reviews (purposive sampling of the literature use of theoretical or topical criteria to include papers on the basis of type, relevance and perceived significance, with the aim of summarising, discussing and critiquing conclusions) and meta-syntheses using definitions provided by Mair et al. [13].

To be included, a paper had to be a review of the causes of the evidence to practice gap for complex interventions in primary care. As our primary focus was professional behaviour change, we excluded reviews that only examined patient behaviours.

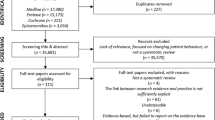

Study selection

Duplicate references were deleted and titles, and abstracts of all the records obtained from the search were independently double-screened. The primary review author, RL, screened all identified citations (titles and abstracts) for potential inclusion; co-authors acted as the second reviewers. In the first instance, a sample of 20 % of citations was screened by RL and other authors (~100 citations each). Following this, the group met and had an in-depth discussion to resolve any uncertainty or disagreement about applying the inclusion/exclusion criteria before screening the remaining citations. RL obtained the full text of potentially eligible articles which were assessed for eligibility against the pre-specified inclusion and exclusion criteria by two reviewers (RL, EM) working independently. Any discordance or uncertainty was resolved through discussion between the two reviewers initially and the involvement of a third reviewer as necessary. Reasons for exclusion were recorded and are presented in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram [21].

Data extraction

For all eligible full text articles, data were extracted by a single reviewer (RL) using standardised structured data abstraction forms. The content of the data abstraction forms were reviewed for validity by the co-authors with extensive experience in systematic review methodologies and implementation/evaluation of complex interventions, to ensure all key information from the included reviews were captured. Data extracted included the following: author, year, title, objective, setting, eligibility criteria for selecting studies, synthesis method, number of and design of included primary studies, use of theoretical framework(s). Data extraction was checked by co-authors for a sample of 25 % of all included reviews, using a quality assurance form. The papers were randomly selected from each review topic or category (e.g. guideline, technology, prescribing behaviour) (Additional file 2) to ensure same level of quality assurance was carried out in all review categories.

For this review, as we aimed to synthesise a body of qualitative literature and not determine an effect size, we did not undertake a formal quality appraisal of the included reviews [22]. However, we have described the degree to which each included review conformed with the PRISMA checklist [21].

Data synthesis

Data were synthesised using principles of meta-ethnography [23, 24], based on an iterative, interpretive and inductive approach. Meta-ethnography rests on the reviewers’ interpretation of the findings, which may include themes, categories and relationships, arising from the data of the original findings, to produce new interpretations that incorporate the meanings of the included studies [25].

The first stage seeks to determine how the studies are related; this can be achieved by creating a list of initial themes or concepts used in each account. Initially, we extracted key information and concepts from results and discussions of the included reviews; this included the main themes related to the causes of the evidence to practice gap. Data from discussions were extracted because they often contained further interpretations from the reviewers, which provided important insights. Attempts were made to differentiate between interpretations made by the original authors based on the primary data and those made by the authors of the reviews, although this was not always possible.

The second stage involves translating the studies into one another (comparisons between studies with regards to key themes/concepts) [26]. This process allowed the identification of common and recurring elements (or translation of the results of the papers into a common form) in the literature by reading the reviews again, taking into account the extracted data, and grouping similar concepts in the extraction grid as themes [23]. These themes formed columns of the grid, and a row for each review was created. The construction of this grid allowed the relationships between themes and between reviews to be explored. A pilot synthesis was carried out using a sample of 20 papers which was reviewed and discussed extensively by the authors, before undertaking further analysis. To preserve the meaning of the included studies, the terminology used in each review was maintained within the grid. Each theme was carefully defined (also known as descriptors) to facilitate coding, by the primary author (RL) with input from all authors. The list of descriptors was reviewed repeatedly by the authors and refined. Data were re-categorised from one construct to another, and some constructs were refined and re-configured if necessary [23]. Any uncertainty about coding was discussed between RL, EM, FS and BNO. When each concept from the reviews had been translated into the grid, all the authors examined and commented on the themes and data within the grid to ensure all data were coded into appropriate constructs, and a final version was agreed. Following such iterative and rigorous process of data synthesis, 25 % of included reviews (randomly selected from each review topic or category) were double-coded by the co-authors using a quality assurance form.

The third stage involves synthesising translations which include three main forms of synthesis: reciprocal (concepts are common and recurring); refutational (concepts are conflicting across included reviews); and line of argument where an overarching narrative is developed that summarises and represents the key findings of the included reviews [23]. Following the review of the grid (mapping of data onto the constructs), the authors collectively agreed that the relationships between included reviews appeared to be reciprocal, with many common themes occurring across studies and from which a line of argument could be constructed. The line of argument synthesis is described in the “Results” section, presented in the form of a conceptual framework and also in the “Discussion” section where the interpretations of the data are discussed and implications for clinical practice and future research are described.

This systematic review is reported in accordance with the ENTREQ statement guidelines to enhance transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research (see Additional file 3) [27]. The full version of the review protocol was published elsewhere [22]. This systematic review was part of a NIHR SPCR funded project (SPCR FR4 project number: 122). The systematic review protocol was registered on the PROSPERO database (CRD42014009410).

Results

Identification of relevant reviews

Searches of the five electronic databases to December 2013 yielded a total of 6164 potentially eligible papers. After screening of titles, abstracts and full text papers, 70 reviews were included. Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow diagram of study selection.

Characteristics of included reviews

None of the included papers used the term “cause” or intended to investigate causes of the second translational gap. It quickly became apparent that a descriptive approach prevailed with the included papers expressing “causes” in terms of “barriers and facilitators” to implementation; hence, we adopted this approach despite being aware of the criticisms of this in the literature [28]. Of the 70 included papers, 64 reported barriers, 49 reported facilitators, and 46 reported both. Reviews encompassed a wide range of different topic domains: 13 reviews focused on research evidence/guideline implementation, 11 on quality of care and disease management, 26 on technology based intervention implementation, 12 on public health and prevention programmes, 6 on role integration/collaborative working, 1 on prescribing and 2 on others. Details of how topics were categorised are described in Additional file 2. Thirty-two reviews (46 %) included original studies from primary care only, with the rest including studies from mixed health care settings.

Eighteen reviews (26 %) were undertaken in the United States of America (USA), 16 (23 %) in Canada, 15 (21 %) in the UK, 8 (11 %) in Australia and 10 (14 %) in Europe. The number of original studies included in the reviews ranged from 2 to 225. The primary studies included in the reviews had been undertaken in developed countries worldwide, with 17 reviews stating that the original studies were predominantly conducted in the USA. Seventeen reviews included only quantitative studies, 4 included only qualitative studies and 30 included both quantitative (e.g. survey) and qualitative studies. Data came from multiple perspectives including health care professionals and administrative staff. Details of included reviews can be found in Table 1.

Methodological quality of included reviews

The level of methodological detail reported varied across reviews. Sixty-eight reviews (97 %) reported the use of explicit inclusion/exclusion criteria. Screening and data abstraction process were adequately described (e.g. independently, in duplicate, use of piloted forms, as per PRISMA checklist [21]) in 45 reviews (64 %). Thirty-nine reviews (56 %) summarised the study selection process (as a form of flow chart and/or described in the text) and the characteristics of included primary studies.

Thirty-two reviews (46 %) critically appraised their included primary studies using some form of checklist/assessment, e.g. the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) [29] and Pluye’s mixed methods review scoring checklist [30], or described quality issues in the “Results” or “Discussion” section. Theoretical frameworks were described in 25 reviews (36 %). Many of them used theory to explain the findings in their discussion or as part of their introduction or background [3, 13, 16, 31–43]. Relatively few of the reviews used theoretical frameworks as a way to carry out their analysis [32–34, 41, 43, 44]. Examples of theories discussed in the reviews included the Diffusion of Innovations Theory [45], Normalization Process Theory (NPT) [46], the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [47], Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) [48] and the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) framework [49, 50]. Further information about methodological quality (e.g. type of critical appraisal checklist or assessment form used by the included reviews) can be found in Table 1.

Final conceptual framework

A total of 21 primary themes and 40 secondary themes emerged from the data and were classified into the four levels of external context, organisation, professionals and intervention, described in detail below. Examples of quotations from the included reviews are provided to illustrate themes in Table 2. Many reviews mentioned the dynamic relationships among factors as an important issue in implementation. However, almost all reviews presented individual barriers and/or facilitators as separate concepts without exploring how the barriers and facilitators interacted or their relative importance. Overall, there was a lack of information about the context in which the different barriers and facilitators occurred. All the themes drawn from the identified reviews were treated equally and attributed the same weight independent of their frequency to avoid problems arising from potential “double counting” of primary studies included in several reviews. The final conceptual framework describing the different levels is presented in Fig. 2.

External context

Policy and legislation. The presence of supportive national and local policies which were mandatory and appropriate legislative mechanisms often acted as potent activators [51] and promoted implementation of clinical guidelines, telemedicine and new roles (e.g. nurse practitioners) [34, 52–56]. Secondary themes associated with policy and legislation included fit with local or national agenda, where compatibility between interventions and local or national policies, or an organisation’s mission, priorities and values promoted adoption [16, 32]. Conversely, the lack of stated goals and objectives reflecting priorities and directions could act as barriers [57]. Similarly, the regulatory framework, particularly where it was restrictive or absent was found to impede implementation [41, 51, 58]. Presence of codes of practice: having standards (usually at the local level) to ensure quality and uniform practice and establishing guidelines for how work gets done were shown to promote implementation.

The presence of clear incentivisation structures was found to drive adoption: this included non-financial incentives such as public recognition [59] and access to training [60, 61]. Financial incentives were shown to facilitate adoption, e.g. governmental incentives for use of health information technology, quality and outcome frameworks that linked to targets for prescribing [33]. There were concerns from professionals about the lack of finance to incentivise adoption of new processes or interventions [62]. Financial penalties could lead to distrust and professional demoralisation [3].

Dominant paradigms refer to the presence of commonly held set of values or beliefs in a society at a given time, e.g. evidence-based practice and patient centred care. Professional organisations such as those producing national guidance and advice to improve health care and the political agenda impact upon the credibility and enactment of these commonly held values [33]. Another example included the advocacy of certain drugs by pharmaceutical industries [63].

Buy-in by internal or external stakeholders at different levels promoted implementation through multidisciplinary effort and by having stakeholders aligned with an implementation plan [16]. Conversely lack of stakeholder buy-in [64], resistance or competing priorities or lack of interest from stakeholders was found to impede implementation [54]. Infrastructure: short comings, from unreliable internet access, lack of access to information, lack of mechanisms or systems to support storing or documenting information or lack of infrastructure support for implementation were all reported to impede implementation, whereas presence of these features promoted implementation.

Advances in technology in health care have become increasingly salient. Technologies change health care delivery and the way in which information is provided (e.g. electronic patient records, telemedicine). There is a growth of interest in their use [65], and this is shown to drive implementation. Economics and financing including the economic climate, the ways in which the government allocated funding, and investment decisions made by local health authorities were shown to affect implementation of guidelines [66] and new roles [54, 55]. Finally, public awareness could result in pressure to introduce a new intervention. This was presented as a facilitator for motivating the uptake of telemedicine and for educating the public about new nurse practitioner roles [34, 55].

Organisation

The presence of a positive culture which was receptive to change and valued innovation was viewed as important for implementation [32, 41, 58]. Strong and consistent internal and external leadership including identifying influential champions who were respected and trusted by staff to drive change and implementation and communicate vision, from the beginning of the project had a positive impact on adoption. Conversely, lack of effective leadership to advocate change, set priorities or manage the implementation process; and changes in leadership were presented as barriers [55, 67–69]. Organisational readiness is defined as the degree of preparation before implementation: lack of staff preparation or strategic planning (e.g. resource planning, implementation plan) was found to be a barrier which could be influenced by the practice environment (e.g. small practice size, inadequate practice organisation). A hierarchical structure, defined as the degree to which the organisation prescribed roles or responsibilities and/or promoted autonomy was mainly presented as a barrier [44, 54, 67].

Available resources, including time, funding, staff and technical support, were commonly reported as both barriers and facilitators. Limited funding in general, lack of time to plan [16] or train staff [51], insufficient equipment [3, 70] or administrative support to perform additional data entry or deal with paperwork [31, 67, 71, 72] were reported as barriers. Other related barriers included failure to adequately anticipate the amount of time and costs, including operational and training costs [34, 35, 44], costs associated with ongoing maintenance [34, 41] and the amount of technical assistance and support required at all stages of the project, e.g. some resources available to support the project at the beginning but insufficient for its completion [67].

Processes and systems were defined as the extent to which the intervention fitted with existing workflow and how well it integrated with current working processes and systems. When the fit was good [14, 73, 74], for example, when e-prescribing was sufficiently integrated as part of clinician workflow, work process was improved [14]. Achieving good fit sometimes required redesign of delivery systems or workflow.

Relationships, both between professionals and between professionals and patients were found to influence implementation. Positive and trusting inter-professional relationships through the presence of bi-directional communication and giving staff abundant opportunity to discuss salient matters and provide input to challenges before and during implementation were perceived to be facilitators [32, 41, 55]. Conflict with patient expectations [75] and concerns about patient and health professional interaction, for example, when using the new information system, nurses spent more time on documentation than on direct care [31], could lead to a decrease in acceptability of an intervention and subsequently impede implementation.

Skill mix issues, including clarity of role and responsibility and division of labour, were presented as both barriers and facilitators. A lack of clarity about accountability leading to confusion about who should be responsible for implementing the changes could constitute a barrier [76]. For instance, in relation to e-prescribing, clinicians did not want to solve implementation problems and believed this should be done by non-clinical staff [14]. The nature of the division of labour, defined as the allocation of responsibilities and the appropriate use of skills to accommodate new processes or implementation was also a factor that emerged from some reviews. The absence of personnel with the right combination of skillset or a lack of appropriate expertise to perform specific tasks (e.g. business and medical personnel with the informatics expertise to develop strategic plans for health information exchange or electronic sharing of health related information) [44, 67] were found to impede implementation. By contrast, flexibility of skill mix incorporating an interdisciplinary approach was shown to facilitate implementation. Non-clinical staff often had better knowledge of optimising processes compared to clinicians [77], and different members of the workforce brought different perspectives and skills to the implementation [77].

Involvement—support from team members and management; collaborative working and shared vision. Support from peers, colleagues and superiors, active engagement of both clinical and non-clinical staff, continuous communication from senior management about the importance of change and its consistent commitment were shown to facilitate implementation [32, 41, 60]. A team-based partnership approach, collaborative efforts and good coordination between stakeholders and organisations were all shown to be important for implementation [34, 41, 55, 77]. Collaborative processes can be characterised as being facilitated by non-hierarchical relationships, mutual respect or trust and open communication among individuals, as well as shared decision-making to determine how the intervention can or should be implemented and the ability to reach consensus when there is disagreement [32]. Shared vision, defined as a collective understanding and agreement on goals, importance and benefits of the intervention and mutually held realistic expectations about the work required for implementation, for instance, a collective understanding of resources required for implementing change and that cost savings might not occur in the short term, due to decreased productivity during implementation, was presented as both a facilitator and a barrier [16, 32, 41, 54, 77].

Professionals

Themes within this level included perceptions of what it meant to be a professional—professionalism, peer influence, sense of self-efficacy and authority/influence. Professionalism, which included using professional judgement to apply scientific and experiential knowledge and dealing with uncertainty, was viewed as a salient aspect to be considered in relation to implementation. Concerns about reduced autonomy or trust, independence of practice or inability to practise to full scope were all shown to impede implementation [16, 31, 35, 39, 54, 55]. Peer influences, for example, negative attitudes or beliefs of colleagues towards information and communication technology were perceived as barriers to implementing the intervention. Moreover, a lack of confidence in one’s own ability to carry out specific tasks and the feeling of not having authority or enough influence to change or carry out the procedures were found to impede implementation [31, 66].

Underlying philosophy of care includes personal style and relationship between health professionals and patients. Personal style, defined as the perceived fit between the intervention and the preferred style of clinical practice, such as clinicians’ communication style [78, 79], personality [54] and philosophical opposition to the intervention [69, 76], were presented exclusively as barriers. Additionally, patient values and preferences [3, 33] and concerns about clinician-patient relationships [42, 77] impeded implementation (e.g. concerns that new systems would affect clinician-patient relationship).

Attitudes to change, prior experience, motivation and priority, familiarity and awareness, perception of time and workload. Attitudes and beliefs are shaped by personal beliefs and experience, education and training and peer networks. This was perceived as an important aspect to consider in relation to implementation and was reported as both a barrier and a facilitator. Resistance to change caused by disagreement with the evidence, negative beliefs about the usefulness or added value of the intervention or belief that the intervention was not part of their role were commonly described as a barrier to implementation [3, 14, 35, 41, 67–70, 76, 77, 80]. Previous personal experience in clinical practice or with the information system affected professional attitudes to a new system or intervention [54, 66, 77, 81]. Competing priorities [42, 57, 59, 62, 63, 70, 82], lack of motivation [31, 39, 42, 57, 68, 81] and low awareness of the intervention [31, 35, 38, 39, 43, 44, 68, 75, 80, 81] were shown to impede implementation. Further, perceived shortage of time, for example, to plan or implement new ideas, to carry out new interventions or procedures or to learn new skills, were commonly presented as a barriers in the included reviews [3, 17, 31, 36, 38–40, 43, 62, 70, 75, 79, 81, 83]. Additional workload caused by the implementation of new complex interventions was also found to hinder adoption [17, 31, 44, 54, 66, 81, 84].

Lastly, competencies, e.g. adequate training and good computer experience/skills were shown to facilitate implementation [16, 17, 31, 32, 34, 41, 42, 44, 54–58, 60, 67, 70, 77, 80, 81, 84–86].

Intervention

The nature and characteristics of the intervention which included the complexity of the intervention, evidence of benefit, applicability and relevance, costs of an intervention, cost-effectiveness of an intervention, clarity, practicality and utility of intervention, customisation of intervention and IT compatibility were all viewed as aspects to be considered during implementation. Interventions that were complex were often associated with lower adoption [3, 35, 39, 87, 88]. By contrast, interventions that demonstrated clear and consistent clinical evidence of benefit [3, 16, 34, 35, 51, 55, 56, 68, 74, 89] or good applicability relevant to setting [3, 35, 68] were shown to facilitate implementation. The costs of an intervention and whether practices could obtain a positive return on investment [51] and in particular the time invested [42, 51] were considered to be features that would promote implementation. A lack of cost-effectiveness evidence relevant to the setting or poor cost-effectiveness could impede implementation [33, 57]. Additionally, interventions with good definitional clarity, such as well-organised guidelines with well-defined measurable actions that were based on clear strong recommendations, promoted implementation [35, 68]. Complex interventions that demonstrated good design, e.g. an overview of patient information (current health status and patient history) with a follow-up of patient adherence to their prescription and access to laboratory results was a facilitator of implementing e-prescribing [14] and showed good usability and reliability, e.g. user-friendly, easily accessible, fast, provides accurate and up-to-date information, content relevant to user, automatic prompting, information given at the time of decision-making [31, 35, 58, 69, 73, 74, 90] were associated with successful implementation. Customisation of intervention—the degree to which a new intervention can be modified to make it more applicable to specific contexts was a relevant factor. New interventions that could be customised to fit provider needs and preferences, organisational practices, values and cultural norms were shown to promote implementation [32, 37]. In addition, interventions compatible with the current operating IT system were more likely to be implemented [16, 56].

Implementability included the complexity of implementation process, benefit and harm as a result of implementation and resource requirement. The complexity of implementation can be determined by the scale of implementation, number of sites and processes required. Highly complex implementation plans were less likely to succeed as they often required complex project organisation [57]. Effective project management (e.g. using an incremental approach over time according to a strategic plan allowing a transition period between old and new system) was shown to facilitate implementation [77]. Benefit and harm as a result of implementation—adoption of a new intervention or process might bring potential benefit or harm to other aspects of care. For instance, implementing a new intervention usually required shifting organisational priorities and putting other projects on hold which resulted in initial lower productivity and increased staff workload [41, 76]. Conversely, implementation of a new intervention might lead to cost savings or more efficient workflow [51, 58]. Resources required for implementation—effective implementation required sufficient resources and funding to support not only start-up costs but also on-going costs and attention to sustainability [56].

Finally, safety and data privacy were perceived to be important for implementation. With regard to technology based interventions, there were concerns from both health care professionals and patients about the ownership of health information, secure data exchange, unauthorised sharing of confidential information about patients with fear of discrimination based on the health condition [51] and liability if patient information was lost [41]. The presence of sufficient security mechanisms to support trust between providers and patients [34] and technical measures to ensure systems compliance with data protection laws [84] were shown to promote implementation.

“Fit” between the intervention and the context

Our conceptual framework has highlighted the importance of the “fit” between the intervention and the different levels of context (Fig. 2), i.e. external context, organisation and professionals; how well the intervention fits with the external context (e.g. current policy, national or local agenda, existing infrastructure) and whether the organisation’s existing work practices (e.g. culture, readiness, relationships and leadership) and daily work as well as their beliefs and values (professional attributes), will have an impact on the degree of implementation and intervention outcomes. This hypothesis requires empirical testing.

Dynamic nature of barriers and facilitators

The literature suggested that relationships between individual barriers and facilitators are subject to change over time. This was rarely described in great detail. A review of electronic prescribing implementation found a change in individuals’ perceptions between the different stages of implementation. While the users had a less positive view of the intervention during pre-implementation phase, their views became more positive with the increasing use of the intervention during the transition and post-implementation phases. In addition, work processes were viewed as a barrier during the transition phase but became a facilitator when the intervention was formally integrated and work flow was improved [14].

Relevance of contextual factors according to different topic domains/complex interventions

Table 2 shows which contextual factors are related to different complex interventions/topic domains. Dominant paradigm (commonly held set of values or beliefs in a society at a given time), financial incentives, resources, competencies, attitudes to change (in general), inter-professional relationships, evidence of benefit, and safety, confidentiality and liability concerns were common implementation considerations. Wider contextual issues such as policy, infrastructure and organisational culture (except inter-professional relationships) were not perceived as issues relevant to changing prescribing behaviour. Most contextual factors were perceived to be relevant to implementation of E-health technology. Whilst it is useful to know what the likely barriers or facilitators are for implementing certain types of complex interventions, these findings need to be interpreted with caution. The findings might highlight the barriers likely to arise during implementation; however, contextual factors need to be considered as a whole as every organisation is unique and thus may be more or less affected by particular contextual issues.

Discussion

In this systematic review of reviews, we sought to identify the causes, or given explanations or influences operating in the evidence-practice gap, relating to the implementation of complex interventions. We could not examine “causes” of the evidence to practice gap due to the absence of data, as well as the nature of the reviews, particularly the way their analyses were carried out: they mostly used a descriptive approach by reporting individual barriers and facilitators without stating the relationships between them. There is also a lack of information about the context in which these barriers and facilitators occur. A large number of multi-level contextual influences emerged from the included reviews related to the levels of external context, organisation, professionals and intervention. This review has demonstrated the challenges associated with implementation and that implementing any type of change in primary care is likely to be complex. Our conceptual framework has been developed based on published reviews of studies with empirical evidence from different types of complex interventions and topic domains. Its development was different from other existing frameworks or models such as the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) and the Normalization Process Theory (NPT). CFIR was developed using a meta-theoretical approach, combining constructs across published theories or frameworks [47]. NPT was constructed from a sociological perspective [91, 92] and the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) which is an integrative framework of theories of behaviour change developed using an expert consensus process [93]. Despite taking a different methodological approach, the content of our framework (data derived from primary care) is comparable and overlaps considerably with the CFIR which is not primary care specific and has resonance with NPT. This has enhanced the validity of our findings.

Relevant barriers and facilitators are dynamic and likely to change over time [14, 28]. Despite many of the barriers being reported as separate entities in the identified reviews, they are likely to interact with one another and each cannot be considered in isolation [28, 32, 47, 94]. This finding is consistent with the systematic review undertaken by Greenhalgh et al., i.e. many studies failed to address important interactions between different levels and account for contextual and contingent issues [95]. Contextual factors that are perceived as barriers at the beginning of implementation may become facilitators later on in the implementation process [14].

The importance of context in implementation in primary care

This review has highlighted the importance of paying attention to context which is often notably absent from research and frequently fails to be acknowledged, described or taken into account during implementation. It is unclear how it can be described, defined and measured [96]. Bate et al. suggested that context can be studied using mixed methods (e.g. participatory observations, interviews, documentary analysis), in order to get a richer picture of how different contextual factors influence implementation [96]. Other methods such as contextualisation and context theorising have been proposed to address the multi-level and dynamic nature of context [96]. The updated Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance for process evaluation of complex interventions stresses the relevance of taking into account the contextual factors associated with variations in implementation, intervention mechanisms and outcomes [97]. Our review suggests the need to pay attention to the external context as well as the specific context within which a complex intervention is being embedded.

Strengths and limitations of study

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of reviews that provides a comprehensive overview related to the field of implementation in primary care. This review is not restricted to any type of clinical topic or discipline. The broad scope is a strength as we aimed to produce a single document which summarises and synthesises the literature that is easily accessible to clinicians, researchers and policy makers. A key advantage of undertaking a systematic review of reviews is the ability to summarise and synthesise a vast and fragmented literature relatively efficiently. It enables synthesis at different levels, allowing comparisons across different complex interventions, different outcomes and different health conditions or population groups. We could not determine the relative “weighting” of the findings as it would not be appropriate: this is a review of reviews and not of primary studies. Furthermore, this is a qualitative synthesis which focuses on not only the primary studies but also the authors’ interpretations derived from these studies. Our analysis has accounted for all the themes emerged from the included reviews.

Despite our attempt to be as inclusive and comprehensive as possible, the search may not have identified all relevant literature; this risk has been minimised by screening reference lists of all included papers for additional literature. Equally, the reviews included in this article may not have captured all the primary research studies; therefore, some findings may be missed. However, we are confident that this is unlikely to change the conclusions of this review. In addition, formal quality assessment was not undertaken and this could be a potential weakness of the study. Nevertheless, the papers included had to meet the criteria of “review” using the definitions by Mair et al. [13], and an attempt was made to describe and summarise the quality of the reviews using PRISMA. Double coding was only undertaken in a proportion of the included reviews. However, we took a rigorous and cyclic approach through every step in our data synthesis (i.e. extensive involvement and discussions among all the authors in reviewing the extracted data and refinement of concepts at every stage: from pilot synthesis, construction of descriptors and extraction grid, to translations synthesis and the final conceptual framework). Furthermore, the importance of using methods of validation (i.e. use of multiple coders, assessment of inter-rater reliability) and their applicability to qualitative research/evidence synthesis is less clear and controversial [98, 99].

A major limitation is the conceptualisation of factors affecting the second translational gap as “barriers” and “facilitators”. A study exploring the value of “barriers to change” suggested that barriers were constructions used by the participants to make sense of the situation in which they found themselves and implementation studies must look beyond the narrative that is provided by participants [28]. Most original studies included in the reviews are surveys or of accounts of research participants through qualitative interviews or focus groups. Perceptions of barriers may be socially constructed, and addressing them may not necessarily improve implementation [79]. In our work, we could only analyse and report data from included reviews, and despite our initial question focusing on the causes of the evidence to practice gap, the overwhelming dominance of the use of the framework of “barriers and facilitators” required us to also adopt this framework to report on existing data.

Conclusions

We took a multi-level approach to synthesise data from 70 reviews, addressing barriers and facilitators to implementation of complex interventions in primary care. This resulted in the development of a conceptual framework which emphasised the importance and inter-dependence of (1) the external context in which implementation was taking place; (2) organisational features; (3) characteristics of health professionals involved and (4) characteristics of the intervention. Understanding the context, the interplay between facilitators and barriers to implementation and considering the “fit” between the intervention and the context are likely to be essential in determining the degree to which implementation of any one intervention is successful. This evidence-based conceptual framework could be used by health care researchers and/or primary care organisations that seek to improve uptake of effective complex interventions, by identifying and overcoming their context-specific issues.

Implications for research

Despite the identification of a large number of reviews and many topics being discussed, there are gaps in the literature. Studies beyond barriers and facilitators are required and a more explanatory approach (how and why) should be used. Future research needs to focus on articulating how and why each contextual factor is important in influencing the uptake of a particular intervention. In addition, we need to describe the interactions between these contextual influences and understand their relative importance. A more theoretically driven approach may help with understanding, describing, defining and potentially measuring context.

Implications for clinical practice and policy

Implementation of any type of intervention is complex, dynamic and influenced by a variety of factors at the level of external context, organisation, professional and intervention in the primary care setting. Understanding and defining context appeared to be important and the “fit” between the intervention and the context has been highlighted. A list of recommendations was constructed from the review findings and can be found in Fig. 3. Individuals who wish to implement any type of change in their organisation should (1) consider and describe the context they are working in and (2) monitor context periodically as it is likely to change over time.

Abbreviations

- CFIR:

-

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

- MRC:

-

Medical Research Council

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

- NPT:

-

Normalization Process Theory

- TDF:

-

Theoretical Domains Framework

- USA:

-

United States of America

References

Department of Health, innovation, health and wealth: accelerating adoption and diffusion in the NHS. 2011 Dec. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_131299. Accessed 20 Oct 2015.

England NHS. Five year forward view. 2014. http://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct 2015.

Mickan S, Burls A, Glasziou P. Patterns of ‘leakage’ in the utilisation of clinical guidelines: a systematic review. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87(1032):670–9.

Sederer LI. Science to practice: making what we know what we actually do. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(4):714–8.

Runciman WB, Hunt TD, Hannaford NA, Hibbert PD, Westbrook JI, Coiera EW, et al. CareTrack: assessing the appropriateness of health care delivery in Australia. Med J Aust. 2012;197(2):100–5.

Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet. 2003;362(9391):1225–30.

Woolf SH. The meaning of translational research and why it matters. JAMA. 2008;299(2):211–3.

Health & Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC). http://www.hscic.gov.uk/primary-care. Accessed 20 Jan 2016.

NHS England (London region)/primary care transformation programme. Transforming primary care in London: general practice—a call to action. 2013. www.england.nhs.uk/london/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2013/11/Call-Action-ACCESSIBLE.pdf. Accessed 12 Nov 2015.

Salmon P, Peters S, Rogers A, Gask L, Clifford R, Iredale W, et al. Peering through the barriers in GPs’ explanations for declining to participate in research: the role of professional autonomy and the economy of time. Fam Pract. 2007;24(3):269–75.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655.

Smith V, Devane D, Begley CM, Clarke M. Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11(1):15.

Mair FS, May C, O’Donnell C, Finch T, Sullivan F, Murray E. Factors that promote or inhibit the implementation of e-health systems: an explanatory systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(5):357–64.

Gagnon MP, Nsangou ER, Payne-Gagnon J, Grenier S, Sicotte C. Barriers and facilitators to implementing electronic prescription: a systematic review of user groups’ perceptions. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(3):535–41.

Novins DK, Green AE, Legha RK, Aarons GA. Dissemination and implementation of evidence-based practices for child and adolescent mental health: a systematic review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2013;52(10):1009-1025.

Addington D, Kyle T, Desai S, Wang J. Facilitators and barriers to implementing quality measurement in primary mental health care: systematic review. [Review]. Canadian Family Physician. 2010;56(12):1322–31.

Adaji A, Schattner P, Jones K. The use of information technology to enhance diabetes management in primary care: a literature review. Informatics in Primary Care. 2008;16(3):2008.

Royal College of General Practitioners. The future direction of general practice, a roadmap. London: RCGP. 2007. http://www.rcgp.org.uk/policy/rcgp-policy-areas/~/media/Files/Policy/A-Z-policy/the_future_direction_rcgp_roadmap.ashx. Accesseed 12 Nov 2015.

The organisation for economic co-operation and development (OECD). List of current members and partners. 2016. http://www.oecd.org/about/membersandpartners/. Accessed 20 Jan 2016.

Linton JD. Implementation research: state of the art and future directions. Technovation. 2002;22(2):65–79.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):W65–94.

Lau R, Stevenson F, Ong BN, Dziedzic K, Eldridge S, Everitt H, et al. Addressing the evidence to practice gap for complex interventions in primary care: a systematic review of reviews protocol. BMJ Open. 2014;4(6):e005548.

Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park: Sage; 1988.

Walsh D, Downe S. Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: a literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;50(2):204–11.

Jensen LA, Allen MN. Meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Qualitative Health Research. 1996;6(4):553–60.

Campbell R, Pound P, Morgan M, Daker-White G, Britten N, Pill R, et al. Evaluating meta-ethnography: systematic analysis and synthesis of qualitative research. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15(43):1–164.

Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:181.

Checkland K, Harrison S, Marshall M. Is the metaphor of ‘barriers to change’ useful in understanding implementation? Evidence from general medical practice. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2007;12(2):95–100.

Public Health Resource Unit. Critical appraisal skills programme. 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research. England: Public Health Resource Unit; 2006.

Pluye P, Gagnon MP, Griffiths F, Johnson-Lafleur J. A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in mixed studies reviews. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(4):529–46.

Gagnon MP, Desmartis M, Labrecque M, Car J, Pagliari C, Pluye P, et al. Systematic review of factors influencing the adoption of information and communication technologies by healthcare professionals. J Med Syst. 2012;36(1):241–77.

Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3–4):327–50.

Mason A. New medicines in primary care: a review of influences on general practitioner prescribing. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 2008;33(1):1-10.

Broens TH, Huis in’t Veld RM, Vollenbroek-Hutten MM, Hermens HJ, van Halteren AT, Nieuwenhuis LJ. Determinants of successful telemedicine implementations: a literature study. J Telemed Telecare. 2007;13(6):303–9.

Dulko D. Audit and feedback as a clinical practice guideline implementation strategy: a model for acute care nurse practitioners. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing. 2007;4(4):200-9.

Nilsen P, Aalto M, Bendtsen P, Seppa K. Effectiveness of strategies to implement brief alcohol intervention in primary healthcare. A systematic review. [Review] [47 refs]. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care. 2006;24(1):5–15.

Peleg M, Tu S. Decision support, knowledge representation and management in medicine. Yearb Med Inform. 2006;72–80.

McKenna H, Ashton S, Keeney S. Barriers to evidence based practice in primary care: a review of the literature. [Review] [72 refs]. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2004;41(4):369–78.

Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458–65.

Fitzpatrick LA, Melnikas AJ, Weathers M, Kachnowski SW. Understanding communication capacity. Communication patterns and ICT usage in clinical settings. J Healthc Inf Manag. 2008;22(3):34–41.

Leatt P, Shea C, Studer M, Wang V. IT solutions for patient safety—best practices for successful implementation in healthcare. Healthc Q. 2006;9(1):94–104.

Lu YC, Xiao Y, Sears A, Jacko JA. A review and a framework of handheld computer adoption in healthcare. Int J Med Inform. 2005;74(5):409–22.

Yarbrough AK, Smith TB. Technology acceptance among physicians: a new take on TAM. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(6):650–72.

Yusof MM, Stergioulas L, Zugic J. Health information systems adoption: findings from a systematic review. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2007;129(Pt 1):262–6.

Rogers E. Diffusion of innovations. 5th edition ed. New York: Free Press; 2003.

May C, Finch T. Implementing, embedding and integrating practices: an outline of Normalization Process Theory. Sociology. 2009;43(3):535–54.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50.

Legris P, Ingham J, Collerette P. Why do people use information technology? A critical review of the technology acceptance model. Information & Management. 2003;40(3):191–204.

Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B. Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework. Qual Health Care. 1998;7(3):149–58.

Helfrich C, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Daggett G, Sahay A, Ritchie M, et al. A critical synthesis of literature on the promoting action on research implementation in health services (PARIHS) framework. Implementation Science. 2010;5:82.

Fontaine P, Ross SE, Zink T, Schilling LM. Systematic review of health information exchange in primary care practices. [Review]. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine: JABFM. 2010;23(5):655–70.

Ogundele M. Challenge of introducing evidence based medicine into clinical practice : An example of local initiatives in paediatrics. Clinical Governance. 2011;16(3):2011.

Hoare KJ, Mills J, Francis K. The role of government policy in supporting nurse-led care in general practice in the United Kingdom, New Zealand and Australia: an adapted realist review. [References]. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(5):963–80.

Sangster-Gormley E, Martin-Misener R, Downe-Wamboldt B, Dicenso A. Factors affecting nurse practitioner role implementation in Canadian practice settings: an integrative review. [Review]. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2011;67(6):1178–90.

Dicenso A, Bryant-Lukosius D, Martin-Misener R, Donald F, Abelson J, Bourgeault I, et al. Factors enabling advanced practice nursing role integration in Canada. [Review]. Nursing leadership (Toronto, Ont). 2010;23:Spec-38.

Jarvis-Selinger S, Chan E, Payne R, Plohman K, Ho K. Clinical telehealth across the disciplines: lessons learned. Telemed J E Health. 2008;14(7):720–5.

Eisner D, Zoller M, Rosemann T, Huber CA, Badertscher N, Tandjung R. Screening and prevention in Swiss primary care: a systematic review. International journal of general medicine. 2011;4:853–70.

Lau F, Price M, Boyd J, Partridge C, Bell H, Raworth R. Impact of electronic medical record on physician practice in office settings: a systematic review. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2012;12(10).

Langberg JM, Brinkman WB, Lichtenstein PK, Epstein JN. Interventions to promote the evidence-based care of children with ADHD in primary-care settings. [Review] [36 refs]. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2009;9(4):477–87.

Taylor CA, Shaw RL, Dale J, French DP. Enhancing delivery of health behaviour change interventions in primary care: a meta-synthesis of views and experiences of primary care nurses. Patient Education and Counseling 2011;85(2):315-322.

Johnson M, Jackson R, Guillaume L, Meier P, Goyder E. Barriers and facilitators to implementing screening and brief intervention for alcohol misuse: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. [Review]. Journal of Public Health. 2011;33(3):412–21.

Berry JA, Coverston CR, Williams M. Make each patient count. The Nurse practitioner. 2008;33(2):42-7.

Baker R, Camosso SJ, Gillies C, Shaw EJ, Cheater F, Flottorp S, et al. Tailored interventions to overcome identified barriers to change: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010;17(3):CD005470.

Ohinmaa A. What lessons can be learned from telemedicine programmes in other countries? J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12 Suppl 2:S40–4.

Garg AX, Adhikari NK, McDonald H, Rosas-Arellano MP, Devereaux PJ, Beyene J, et al. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;293(10):1223–38.

Zwolsman S, Te PE, Hooft L, Wieringa-de WM, Van DN. Barriers to GPs’ use of evidence-based medicine: a systematic review. [Review]. British Journal of General Practice. 2012;62(600):e511–21.

Johnston G, Crombie IK, Davies HT, Alder EM, Millard A. Reviewing audit: barriers and facilitating factors for effective clinical audit. [Review] [90 refs]. Quality in Health Care. 2000;9(1):23–36.

Kendall E, Sunderland N, Muenchberger H, Armstrong K. When guidelines need guidance: considerations and strategies for improving the adoption of chronic disease evidence by general practitioners. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2009;15(6):1082–90.

Shekelle PG, Morton SC, Keeler EB. Costs and benefits of health information technology. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2006;(132):1–71.

Vedel I, Puts MTE, Monette M, Monette J, Bergman H. Barriers and facilitators to breast and colorectal cancer screening of older adults in primary care: a systematic review. Journal of Geriatric Oncology. 2011;2(2):85-98.

Holm AL, Severinsson E. Chronic care model for the management of depression: synthesis of barriers to, and facilitators of, success. [Review]. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2012;21(6):513–23.

Pereira JA, Quach S, Heidebrecht CL, Quan SD, Kolbe F, Finkelstein M, et al. Barriers to the use of reminder/recall interventions for immunizations: a systematic review. [Review]. BMC Medical Informatics & Decision Making. 2012;12:145.

Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ. 2005;330(7494):765.

Mollon B, Chong Jr J, Holbrook AM, Sung M, Thabane L, Foster G. Features predicting the success of computerized decision support for prescribing: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2009;9:11.

Parsons JE, Merlin TL, Taylor JE, Wilkinson D, Hiller JE. Evidence-based practice in rural and remote clinical practice: where is the evidence? Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2003;11(5):242-8.

Johnson KB. Barriers that impede the adoption of pediatric information technology. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(12):1374–9.

Ludwick DA, Doucette J. Adopting electronic medical records in primary care: lessons learned from health information systems implementation experience in seven countries. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2009;78(1):22–31.

Nam S, Chesla C, Stotts NA, Kroon L, Janson SL. Barriers to diabetes management: patient and provider factors. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2011;93(1):1-9.

Koch T, Iliffe S, EVIDEM-ED p. Rapid appraisal of barriers to the diagnosis and management of patients with dementia in primary care: a systematic review. [Review] [45 refs]. BMC Family Practice. 2010;11:52.

Stead M, Angus K, Holme I, Cohen D, Tait G. PESCE European Research Team. Factors influencing European GPs’ engagement in smoking cessation: a multi-country literature review. [Review] [73 refs]. British Journal of General Practice. 2009;59(566):682–90.

Johnson BT, Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey MP. Meta-synthesis of health behavior change meta-analyses. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(11):2193–8.

Hearn L, Miller M, Campbell-Pope R, Waters S. Preventing overweight and obesity in young children: synthesising the evidence for management and policy making. Perth: Child Health Promotion Research Centre; 2006.

Wensing M, van der Weijden T, Grol R. Implementing guidelines and innovations in general practice: which interventions are effective? [Review] [166 refs] [Erratum appears in J Cell Physiol 1998 Dec;177(3):499]. British Journal of General Practice. 1998;48(427):991–7.

Orwat C, Graefe A, Faulwasser T. Towards pervasive computing in health care—a literature review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2008;8:26.

Halcomb E, Davidson P, Daly J, Yallop J, Tofler G. Australian nurses in general practice based heart failure management: implications for innovative collaborative practice. [Review] [89 refs]. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2004;3(2):135–47.

Child S, Goodwin V, Garside R, Jones-Hughes T, Boddy K, Stein K. Factors influencing the implementation of fall-prevention programmes: a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies. [Review]. Implementation Science. 2012;7:91.

Renders CM, Valk GD, Griffin SJ, Wagner EH, Van Eijk JT, Assendelft WJ. Interventions to improve the management of diabetes in primary care, outpatient, and community settings: a systematic review. [Review] [74 refs]. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(10):1821–33.

Grilli R, Lomas J. Evaluating the message: the relationship between compliance rate and the subject of a practice guideline. Med Care. 1994;32(3):202–13.

Davis DA, Taylor-Vaisey A. Translating guidelines into practice: a systematic review of theoretic concepts, practical experience and research evidence in the adoption of clinical practice guidelines. Can Med Assoc J. 1997;157:408–16.

Jimison H, Gorman P, Woods S, Nygren P, Walker M, Norris S, et al. Barriers and drivers of health information technology use for the elderly, chronically ill, and underserved. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2008;(175):1–1422

Finch T, May C. Implementation, embedding and integration: an outline of Normalization Process Theory. Sociology. 2009;43(3):535–54.

May C, Mair F, Finch T, Macfarlane A, Dowrick C, Treweek S, et al. Development of a theory of implementation and integration: Normalization Process Theory. Implement Sci. 2009;4:29–4.

Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(1):26–33.

Hage E, Roo JP, van Offenbeek MA, Boonstra A. Implementation factors and their effect on e-Health service adoption in rural communities: a systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:19.

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82(4):581–629.

Bate P, Robert G, Fulop N, Ovretveit J, Dixon-Woods M. Perspectives on context. London: Health Foundation; 2014.

Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:h1258.

Popay J, editor. Moving beyond effectiveness in evidence synthesis. Methodological issues in the synthesis of diverse sources of evidence. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2006.

Armstrong D, Gosling A, Weinman J, Marteau T. The place of inter-rater reliability in qualitative research: an empirical study. Sociology. 1997;31(3):597–606.

Lineker SC, Husted JA. Educational interventions for implementation of arthritis clinical practice guidelines in primary care: effects on health professional behavior. [Review]. Journal of Rheumatology. 2010;37(8):1562–9.

Lovell A, Yates P. Advance care planning in palliative care: a systematic literature review of the contextual factors influencing its uptake 2008–2012. Palliat Med. 2014;28(8):1026–35.

Sales AE, Bostrom AM, Bucknall T, Draper K, Fraser K, Schalm C, et al. The use of data for process and quality improvement in long term care and home care: a systematic review of the literature. [Review]. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2012;13(2):103–13.

Zhang JA, Neidlinger S. System barriers associated with diabetes management in primary care. Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 2012;8(10)):822–7.

[105] Zwar N, Harris M, Griffiths R, Roland M, Dennis S, Davies GP, et al. A systematic review of chronic disease management. Research Centre for Primary Health Care and Equity, School of Public Health and Community Medicine, UNSW. 2006

Saliba V, Legido-Quigley H, Hallik R, Aaviksoo A, Car J, McKee M. Telemedicine across borders: a systematic review of factors that hinder or support implementation. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81(12):793–809.

Waller R, Gilbody S. Barriers to the uptake of computerized cognitive behavioural therapy: a systematic review of the quantitative and qualitative evidence. Psychol Med. 2009;39(5):705–12.

Zheng MY, Suneja A, Chou AL, Arya M. Physician barriers to successful implementation of US Preventive Services Task Force routine HIV testing recommendations. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2014;13(3):200–5.

Clarin OA. Strategies to overcome barriers to effective nurse practitioner and physician collaboration. Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 2007;3(8):538–48.

Davies SL, Goodman C. A systematic review of integrated working between care homes and health care services. BMC Health Services Research. 2011;11:320.

Xyrichis A, Lowton K. What fosters or prevents interprofessional teamworking in primary and community care? A literature review. [Review] [60 refs]. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2008;45(1):140–53.

Acknowledgements

The Evidence to Practice Project (SPCR FR4 project number: 122) is funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research (SPCR). KD is part-funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Research and Care West Midlands and by a Knowledge Mobilisation Research Fellowship (KMRF-2014-03-002) from the NIHR. This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Funding

This study is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research (SPCR).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

EM and BNO designed the study and obtained funding. RL developed and refined the study protocol with contributions from all co-authors (FS, BNO, KD, SE, HE, AK, NQ, AR, ST, RP, EM). RL prepared the manuscript. RL undertook data collection (literature search, data extraction), analysis, interpretation, report writing and drafted the manuscript. All co-investigators contributed to the design, analysis and interpretation and revised the manuscript critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Medline search. Literature search strategy used in MEDLINE. (DOCX 19 kb)

Additional file 2:

Scope of the review-domains and types of complex interventions included in the review. Broad and specific topic domains included in the review, e.g. guidelines on various topics, different types of ehealth interventions. (DOC 29 kb)

Additional file 3:

ENTREQ statement checklist. ENTREQ reporting checklist to enhance transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research. (DOC 43 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lau, R., Stevenson, F., Ong, B.N. et al. Achieving change in primary care—causes of the evidence to practice gap: systematic reviews of reviews. Implementation Sci 11, 40 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0396-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0396-4