Abstract

Background

Appropriate and well-resourced medical internship training is important to ensure psychological health and well-being of doctors in training and also to recruit and retain these doctors. However, most reviews focused on clinical competency of medical interns instead of the non-clinical aspects of training. In this scoping review, we aim to review what tools exist to measure medical internship experience and summarize the major domains assessed.

Method

The authors searched MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, ERIC, and the Cochrane Library for peer-reviewed studies that provided quantitative data on medical intern’s (house officer, foundation year doctor, etc.) internship experience and published between 2000 and 2019. Three reviewers screened studies for eligibility with inclusion criteria. Data including tools used, key themes examined, and psychometric properties within the study population were charted, collated, and summarized. Tools that were used in multiple studies, and tools with internal validity or reliability assessed directed in their intern population were reported.

Results

The authors identified 92 studies that were included in the analysis. The majority of studies were conducted in the US (n = 30, 32.6%) and the UK (n = 20, 21.7%), and only 14 studies (15.2%) were conducted in low- and middle-income countries. Major themes examined for internship experience included well-being, educational environment, and work condition and environment. For measuring well-being, standardized tools like the Maslach Burnout Inventory (for measuring burnout), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (depression), General Health Questionnaire-12 or 30 (psychological distress) and Perceived Stress Scale (stress) were used multiple times. For educational environment and work condition and environment, there is a lack of widely used tools for interns that have undergone psychometric testing in this population other than the Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure, which has been used in four different countries.

Conclusions

There are a large number of tools designed for measuring medical internship experience. International comparability of results from future studies would benefit if tools that have been more widely used are employed in studies on medical interns with further testing of their psychometric properties in different contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In most countries, all doctors must complete a medical internship after completing four to six years of medical education, and before becoming generally licensed and registered with the medical board of that country. This is a structured period where doctors in training transit from supervised learning in medical schools to rapidly assume clinical responsibility under supervision, and it can be challenging [1]. Despite the different terminology from intern, house officer, foundation doctor to resident, they are all under huge pressure: highly demanding working hours, less satisfactory pay and a need for ongoing learning and assessment [2]. Depending on the context, interns may also experience low availability of resources, limited supervision and feedback [3], poor safety climate [4], lack of responsiveness to basic psychological needs that result in rapid burnout and stress [5, 6]. The internship year/years are also the time where these trainees are about to make their first career decisions [7] and they are important in informing opinions about whether they want to continue medicine in that organization and country, and if so which specialty career seems most attractive [8, 9]. Exits after internship have significant financial cost to the host organization and country [10], and evidence from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) suggests substantial exits and migration to high-income countries immediately after qualification [11,12,13], causing “brain drain” and huge financial losses as medical education is heavily subsidized in most countries.

While previous systematic reviews have summarized the tools for assessing clinical [14], procedural [15] and psychomotor skills [16] in medical trainees, there has been a lack of focus on understanding what standardized tools are available to measure the experience of internship training. Moreover, there isn’t a common definition of key areas to measure, and the questions in major national trainee surveys differ substantially in each country [17,18,19]. This limits options for comparison between countries and across time to assess long-term trends or results of interventions/policy changes.

In this scoping review, we aim to fill the literature gap by mapping the existing tools to measure medical internship experience, summarizing the major areas assessed and highlighting the tools used in multiple studies or with psychometric properties assessed directly in the intern population under study. This review may help medical educators, human resource managers and policy makers decide what are the major areas to consider for internship surveys and what are the most appropriate tools available for this purpose.

Methods

We followed the five steps of Arksey and O’Malley method [20] for scoping review to identify the existing tools to measure medical internship experience. We conducted the review in accordance with PRISMA-ScR standards (see Additional file 1).

Identifying relevant studies

In consultation with an experienced librarian, we conducted a systematic search using MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, Education Resource Information Center and the Cochrane Library to obtain relevant articles. We included quantitative studies published between 2000 and 2019 in English only due to time and resource constraints. We combined keyword terms and phrases related to medical interns (intern, foundation doctor, house officer, resident), tools (survey, questionnaire, assessment, evaluation, scale, index, instrument) and experience (experience, environment, culture, supervision, climate, well-being). To reduce the number of studies to be screened, we also excluded keywords related to qualitative studies, other health workforce cadres, and clinical skills (see Additional file 2 for the search strategies).

Study selection

We included studies if they (1) examined pre-licensed/registered medical interns (we hand-searched the study population in that country to ensure the study population are pre-licensed and pre-registered); (2) measured or evaluated the non-clinical aspects of the internship experience on an individual level; (3) used a questionnaire or tool (quantitative design); We excluded studies if they (1) examined undergraduate/graduate medical students undergoing clerkships, qualified doctors, specialists, consultants, residents on one single specialty, other health workers or a mix of different population; (2) measured or evaluated the clinical skills (surgical/procedural skills) of medical interns; (3) used a qualitative approach including interviews and focus group discussions.

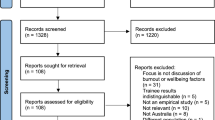

After deduplication, we imported the citations into Abstrackr for initial title and abstract screening [21]. YZ reviewed all the titles and abstracts to assess eligibility for full-text review, and a random subset of 40% were reviewed by PM and MB together. We used Gwet’s AC1 to assess agreement rate between reviewers, which is an agreement coefficient that perform better than Cohen’s Kappa when prevalence is low [22, 23]. The agreement rate on which study to include between YZ and PM + MB for this subset was high (percent agreement 0.96 [excellent], Cohen’s Kappa 0.47 [moderate], Gwet’s AC1 0.96 [excellent]) therefore we proceeded with the full-text review. YZ reviewed all full texts as primary reviewer and either PM or MB acted as secondary reviewer to determine inclusion (percent agreement 0.81 [excellent], Cohen’s Kappa 0.60 [substantial], Gwet’s AC1 0.65 [substantial]). We resolved disagreements on inclusion at title and abstract stage or at full-text stage by discussion among the three reviewers.

Data charting and collation

Three reviewers charted data from included articles and entered them into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. We extracted the following data items: title, authors, year of publication, country of study, study population category, internship training years, the number of hospitals included, sample size, data collection approach, questionnaire type, full questionnaire availability, any standardized scale or questionnaire used, key terms assessed, psychometric properties. We charted key terms by looking into the method, result, tables/figures, and questionnaire appendix when available, and summarizing the key terms as they were defined or reported in their questionnaire or tool (e.g. burnout, depression, supervision, workload, work hours, etc.).

In the current review, we are also interested in whether the studies reported evidence of internal validity and reliability in their study population. We extracted whether the study (1) provided actual evidence of internal validity (face, content, criterion, concurrent, convergent, discriminant, predictive, construct) and reliability (internal consistency, test–retest or inter-rater) tested within their study population [24], or (2) stated they were previously tested or verified but did not test in their study population, or (3) did not mention them.

Summarizing and reporting findings

One aim of this review is to identify and summarize the major themes as a way of categorizing the key areas covered by different studies and tools. Major themes assessed by the tools gradually emerged during title and abstract screening and were refined and finalized iteratively during full-text screening and data charting and collation, developed by repeated discussions amongst the three reviewers (YZ, PM and MB) and an additional author (ME). We finalized with three major themes: well-being, educational environment, and work condition and environment.

We further combined and merged key terms extracted in the last step into sub-themes and placed them under each major theme. For example, under well-being we summarized sub-themes including stress, burnout, etc.; under work condition and environment, we merged work hours and workload as one sub-theme. YZ finalized and categorized the sub-themes and whereas there was uncertainty on the allocation of sub-themes, the uncertainties were resolved by discussions among the three reviewers.

We described the major themes and sub-themes assessed, and how many included studies examined each theme and sub-theme. For reporting of the actual tools, as the purpose of our study was to identify more widely used tools and tools with better psychometric evidence, our reporting focused on the tools that were used in multiple studies, and tools with internal validity or reliability assessed directed in their intern population.

Result

Search results

Figure 1 summarizes the result of the review process. Of 7,027 citations identified after deduplication, 92 met inclusion criteria after the full-text review. The characteristics of included studies are provided in Additional file 3.

Article overview

Publication dates ranged from 2000 to 2019 with more studies published recently (2000–2004, n = 10; 2005–2009, n = 22; 2010–2014, n = 28; 2015–2019, n = 32). The sample size varied from 17 to 91,073, with a median of 172 and interquartile range from 74 to 425. 31 of the included studies specifically examined “interns”, 29 examined “residents”, 12 examined “house officers”, and 10 examined “foundation doctors”. The rest of the studies varied in terms of the study population, e.g. “junior medical officers”, “pre-registration trainees”.

The 92 included studies covered 28 countries with three studies including two countries. The majority of studies (n = 78, 84.8%) identified were conducted in high-income countries including US (n = 30), UK (n = 20), Australia (n = 6), Canada (n = 3) while only 14 studies (15.2%) were conducted in LMICs, e.g. Brazil, India, Malawi, Myanmar, Pakistan, South Africa, Sri Lanka.

Most studies used self-reported questionnaires (n = 89, 96.7%) and data were mostly collected using paper surveys (n = 35, 19 of which were published in or before 2010) or online web surveys (n = 31, 25 of which published in or after 2011). One study used a telephone survey, four used mixed-modes (a combination of paper, online and telephone) and 21 did not specify their survey mode.

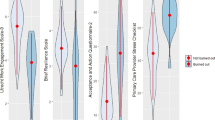

We summarized the key terms examined into three major themes after data charting, collation and summary: (a) well-being, which mostly examined the physical, mental and social condition of the interns; (b) educational environment, which focused on the educational approach, cultural context and physical location where interns experience learning; and (c) work condition and environment, this referred to the aspects of interns’ terms and condition of employment. Figure 2 shows the number of studies focusing on different themes of the internship experience. Of the 92 studies included, 53 examined well-being, 57 examined educational environment and 44 examined work condition and environment. 47 studies examined more than one theme while 15 studies examined all three themes. Table 1 presents the most commonly assessed sub-themes within these themes, and tools that were used in multiple studies, and tools with internal validity or reliability assessed directed in their intern population.

Regarding psychometric properties, 75 studies did not test for internal validity in their population although 37 of these 75 studies mentioned that the tool used was previously validated in other studies. Of the 17 studies with actual evidence of internal validity assessment in their study population, 12 tested for construct validity, seven for face validity, four for concurrent validity, three for discriminate validity, two for content validity, one for convergent validity, and one for predictive validity. 64 studies did not test for reliability in their population but 15 of these studies reported that the tool was previously tested for reliability. Of the 28 tools that provided reliability evidence in their study population, internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was the most commonly reported reliability assessment (n = 27), followed by test–retest reliability (n = 3) and inter-rater reliability (n = 1).

Well-being

53 studies examined well-being in interns. The most assessed sub-themes included stress or psychological distress (n = 28), job satisfaction (n = 14), depression (n = 12), sleep (n = 11) and burnout (n = 10). Other studies also assessed fatigue, quality of life, etc.

The most commonly used tools to assess well-being included the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI, n = 6) for measuring burnout, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9, n = 6) for depression, General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12 or 30, n = 5) for psychological distress, Perceived Stress Scale (n = 4) for stress, and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS, n = 3) for anxiety and depression. Most studies did not report actual psychometric properties in their population, for the commonly used tools such as MBI and GHQ authors reported that they were previously tested for validity and reliability. One study tested reliability for PHQ-9 and PSS in US interns and both showed good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.74–0.85 for PHQ-9 and 0.82–0.90 for PSS) [25]. Another study tested the reliability of HADS in a UK house officer population and indicated that HADS has low internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.53) [26].

The rest of the tools were only used once or twice in the included studies. There was no widely used tool for job satisfaction, and tools used for this sub-theme varied in each study from scales [27, 28] to a single question on job satisfaction [29, 30]. Detailed information on the rest of the tools categorized as measuring well-being and the other two themes are provided in Additional file 4.

Educational environment

57 studies examined the educational environment of interns. Supervision (n = 26), support (n = 16), teaching (n = 14), preparedness (n = 14) and teamwork (n = 14) were the top assessed sub-themes. There were also 15 studies that specifically defined learning or educational environment. Only six studies included handoff and five others included career development.

Of the tools most used to assess educational environment, two of them were large-scale surveys administered in the UK and the US, these reports did not provide validity or internal reliability evidence in the paper published. The UK Medical Career Research Group survey was mentioned in five studies [29,30,31,32,33], which covered different sub-themes including support, handoff, induction, supervision, teaching, feedback, preparedness; and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Resident Survey (ACGME) was cited in two studies [34, 35] that assessed teamwork, educational experience and handoff. The other two tools that were used more than once were developed as a stand-alone tool/scale: the Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure (PHEEM) was used in four studies including in UK (where it was originally developed) [36], Australia [37], Greece [38] and Sri Lanka [39]. PHEEM includes three sub-scales including perceptions of role autonomy, teaching and social support, and has 40 questions in total. It asks specific questions on teaching, supervision, support, feedback, teamwork, communication, induction and career development in regard to the educational environment. PHEEM has shown good reliability in the UK and Sri Lanka (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93 and 0.84, respectively) and face validity and construct validity [36, 39]. The Junior Doctor Assessment Tool was used twice in Australia in which the supervisors assess and rate the communication skills (three questions), professionalism (three questions) and clinical management skills (four questions) of the junior doctor [40, 41]. The tool showed good construct validity and internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88) [40].

Work condition and environment

Out of 44 studies that assessed work condition and environment of interns, workload or work hours (n = 35), safety (n = 14), harassment or bullying (n = 11), food and accommodation (n = 10) were the most examined sub-themes. Workload or work hours were usually assessed through actually asking duty hours [25, 42, 43] or perception of workload [29, 33, 44]. Pay and remuneration and hospital infrastructure (equipment/commodity availability) were less mentioned in the survey.

There was a significant overlap between tools used in this theme and the educational environment theme. For example, four studies used PHEEM which also covered safety, work hours and harassment [36,37,38,39]; three used the UK Medical Career Research Group survey [29, 30, 33] which included questions on workload, harassment or bullying, food and accommodation; two used the ACGME Resident Survey which also included questions on safety and workload [34, 35]. Three separate tools were used in two studies to understand safety issues in the internship period including the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire, Speaking Up Climate, and Psychological Safety Scale [45, 46]. In the first study, Speaking Up Climate was used in residents from the US to compare against Safety Attitudes Questionnaire, and had good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.79) and discriminant and concurrent validity [46]. The second validated the Psychological Safety Scale in another US resident population with good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76) and concurrent validity [45].

Discussion

This review summarized tools designed to measure medical internship experience. We defined “internship” as the period where doctors in training gain supervised experience working in accredited positions in hospital settings before they are fully licensed and registered to practise unsupervised. We adopted a wide definition of internship experience and summarized the areas examined in 92 articles into three major themes (well-being, educational environment, work condition and environment). We found more tools that have be used in multiple settings for well-being, and less tools for the other two themes.

Medical internship is an important period though less examined or emphasized when compared to medical students or licensed doctors. Failure to account for providing appropriate and well-resourced internship training could lead to challenges in recruiting and retaining these health professionals contributing to the global shortage of physicians, as the internship period appears to be a critical time in career decision-making for most medical graduates [7]. Medical graduates are soon to be registered and licensed, decide on a specialty or even migrate to another country citing reasons including negative experience as an intern [47], dissatisfaction with the health organization [8] and risky working environment [48]. While there has been increasing emphasis on physician burnout and how that threatens quality of care especially patient safety [49, 50], it is largely focused on more senior practitioners. However, burnout is also prevalent among interns and junior doctors [5] including in our included studies [51, 52], and often times interns are at the frontline of patient management especially in LMICs [53].

It should be noted that there wasn’t a common definition of “internship experience” across different studies and the key areas to measure. The questions included for several major national trainee surveys like the UK General Medical Council (GMC) National Training Survey and the ACGME resident/fellow survey also vary significantly. These larger trainee surveys, conducted by the medical councils, are not exclusively for interns and also their primary objective is to monitor and report on the quality of medical education and training therefore they are less focused on trainee wellness and personal development. For example, the GMC National Training Survey did not include any questions related to well-being until 2019 when a burnout inventory was added [17] and the ACGME resident/fellow survey on well-being only covered questions on “instruction on maintaining physical and emotional well-being”, “program instruction in when to seek care regarding fatigue and sleep deprivation; depression; burnout; substance abuse” [19]. Moreover, these surveys are tailored to the regulations of that specific country and therefore might not be easily translated to other countries, limiting options for comparison across countries.

Most studies were conducted in high-income countries, whereas only 14 studies out of 92 were conducted in LMICs. The fact that few studies have been conducted in LMICs reflects the neglect of this issue in countries with the most significant shortage of doctors [54], and where higher proportions of medical students and interns intend to migrate after qualification citing dissatisfaction with their education and training and poor working conditions [11,12,13]. This not only leads to “brain drain”, but also great economic losses to the LMICs of origin. Some LMICs try and enforce contracts binding interns to a further minimum period of work post-licensure in their country. However, the governments, medical schools and medical councils should also consider methods to reduce ‘push factors’ such as improving conditions for medical students, interns and junior doctors, and optimizing their experience throughout their training and professional career [55].

For well-being, we found that studies commonly examined stress and psychological distress, job satisfaction, depression, sleep, burnout and anxiety. More standardized tools have been in use to measure these sub-themes other than sleep and job satisfaction. Despite widely used across different populations and settings [56,57,58,59], tools like MBI and GHQ did not have evidence presented for internal validity and reliability in our included studies. We recommend that these previously validated tools be tested in new contexts and populations when used.

For educational environment, most studies included questions on supervision, teaching, support, but few examined induction, communication, career development which perhaps should be given more emphasis career decisions are commonly made during the internship period [7]. There has been a lack of widely used tools in interns other than PHEEM. A previous systematic review also suggested the use of PHEEM for postgraduate medicine’s educational environment [60]. Most other widely used tools for this theme that we included in our analysis either was tailored to specific country settings (e.g. the ACGME survey [34, 35] and UK Medical Career Research Group survey [29,30,31,32,33]) or only focused on specific sub-themes. Given its greater use, we recommend the further adaptation and use of PHEEM to measure educational environments and enable comparison across settings.

Lastly, for work condition and environment, workload, safety, pay and remuneration were more commonly examined in our included studies. Infrastructure, e.g. equipment and commodity availability were less measured which might reflect the limited number of studies conducted in LMICs. We also did not identify any widely used tools other than PHEEM. While PHEEM does include questions on safety, questions are limited to two on physical safety and no-blame culture [36]. To gain a better picture of this topic we recommend the use of additional tools on safety or safety climate as transforming organizational culture may be critical to improving patient outcomes. Also noteworthy for LMICs there should be questions on pay and remuneration, as together with infrastructure and resource adequacy these factors are commonly cited as reasons for poor internship experience [61].

The list of the tools we reviewed that measured medical internship experience could be of interest to researchers, medical educators, human resource managers and policy makers. Depending on the areas of interest, we recommend the tools that have been widely used in different settings and with sufficient evidence of psychometric properties, for example as listed in Table 2. For surveys that aim to provide a more comprehensive assessment of internship experience, e.g. a national intern survey, we recommend that all three of the major themes we identify be covered. We also strongly suggest continued testing and reporting of internal validity and reliability when using such tools in new contexts and specific populations. In the future, the development of a comprehensive “internship experience tool” might allow comparison across countries and time.

Several limitations should be considered for this review. To start with, this was a scoping review, therefore we did not aim to systematically assess the quality of included studies. While we reported on the psychometric properties for each study, we only focused on whether they tested for internal reliability and validity within their population. We did not report the tools that were only used once in our included papers and cited that their tools were “previously validated” in other populations. Tracing back to the original reports to check whether the earlier validation work could have improved our report. Second, during our screening, we found different terminology for our study population including house officer, resident, junior doctor, trainee doctor. For those less-commonly used terms, we hand-searched other resources on the requirement for license and registration in the country of study to ensure the population was pre-registered/licensed. However, we may have missed several studies on interns. Additionally, for studies that examined US residents, we excluded those that only investigated one specialty (e.g. surgery residents) considering that their areas of focus might be on the individual specialty instead of general experience. For some studies on US resident we had to assume the population was pre-licensure, however, some included all residents from first to sixth or seventh year [62, 63] and therefore might not be comparable with an intern in other settings. Last but not least, our disaggregation of themes and sub-themes was based on analysing and interpreting the studies’ methods, results, tables and figures. Only half of the included studies provided their actual questionnaire in the paper or appendix and this made the thematic analysis challenging. To address this, each study was examined by two reviewers to extract key terms and a list of sub-themes was formed iteratively and emergently during the data extraction process.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we identified and described a large number of tools designed for or used to measure medical internship experience. Of these, we recommend future work employs those with more extensive prior use in different settings and with sufficient evidence of adequate psychometric properties. We also recommend future work to adapt and develop a broad internship experience tool that allows comparison across countries and time that can also be used to address the relative lack of research in LMICs.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.

Abbreviations

- ACGME:

-

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Resident Survey

- GHQ:

-

General Health Questionnaire

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- LMICs:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- MBI:

-

Maslach Burnout Inventory

- PHQ:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire

- PHEEM:

-

Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure

References

Gome JJ, Paltridge D, Inder WJ. Review of intern preparedness and education experiences in General Medicine. Intern Med J. 2008;38:249–53.

Daugherty SR, DeWitt C, Baldwin J, Rowley BD. Learning, satisfaction, and mistreatment during medical internship: a national survey of working conditions. JAMA. 1998;279:1194–9.

Bola S, Trollip E, Parkinson F. The state of South African internships: a national survey against HPCSA guidelines. S Afr Med J. 2015;105:535.

Martinez W, Lehmann LS, Thomas EJ, Etchegaray JM, Shelburne JT, Hickson GB, et al. Speaking up about traditional and professionalism-related patient safety threats: a national survey of interns and residents. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26:869–80.

Rodrigues H, Cobucci R, Oliveira A, Cabral JV, Medeiros L, Gurgel K, et al. Burnout syndrome among medical residents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0206840.

Facey AD, Tallentire V, Selzer RM, Rotstein L. Understanding and reducing work-related psychological distress in interns: a systematic review. Intern Med J. 2015;45:995–1004.

Scott A, Joyce C, Cheng T, Wang W. Medical career path decision making: a rapid review. Sax Institute, Ultimo, New South Wales; 2013. https://www.saxinstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/REPORT_Medical-career-path.pdf.

Smith SE, Tallentire VR, Pope LM, Laidlaw AH, Morrison J. Foundation Year 2 doctors’ reasons for leaving UK medicine: an in-depth analysis of decision-making using semistructured interviews. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019456.

Spooner S, Pearson E, Gibson J, Checkland K. How do workplaces, working practices and colleagues affect UK doctors’ career decisions? A qualitative study of junior doctors’ career decision making in the UK. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e018462.

Gauld R, Horsburgh S. What motivates doctors to leave the UK NHS for a “life in the sun” in New Zealand; and once there, why don’t they stay? Hum Resour Health. 2015;13:75.

George G, Reardon C. Preparing for export? Medical and nursing student migration intentions post-qualification in South Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2013;5:483.

Deressa W, Azazh A. Attitudes of undergraduate medical students of Addis Ababa University towards medical practice and migration, Ethiopia. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:68.

Syed NA, Khimani F, Andrades M, Ali SK, Paul R. Reasons for migration among medical students from Karachi. Med Educ. 2008;42:61–8.

Kogan JR, Holmboe ES, Hauer KE. Tools for direct observation and assessment of clinical skills of medical trainees: a systematic review. JAMA. 2009;302:1316–26.

Morris MC, Gallagher TK, Ridgway PF. Tools used to assess medical students competence in procedural skills at the end of a primary medical degree: a systematic review. Med Educ Online. 2012. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v17i0.18398.

Jelovsek JE, Kow N, Diwadkar GB. Tools for the direct observation and assessment of psychomotor skills in medical trainees: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2013;47:650–73.

UK General Medical Council National training surveys. https://www.gmc-uk.org/education/how-we-quality-assure/national-training-surveys. Accessed 14 Sept 2020.

Ireland Medical Council - Your Training Counts. https://www.medicalcouncil.ie/news-and-publications/reports/your-training-counts-.html. Accessed 14 Sept 2020.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Resident/Fellow and Faculty Surveys. https://www.acgme.org/Data-Collection-Systems/Resident-Fellow-and-Faculty-Surveys. Accessed 14 Sept 2020.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

Wallace BC, Small K, Brodley CE, Lau J, Trikalinos TA. Deploying an interactive machine learning system in an evidence-based practice center: abstrackr. Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGHIT International Health Informatics Symposium New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2012 [cited 2020 Sep 9]. p. 819–824. https://doi.org/10.1145/2110363.2110464

Cicchetti DV, Feinstein AR. High agreement but low kappa: II. Resolving the paradoxes. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43:551–8.

Gwet KL. Handbook of inter-rater reliability, 4th edition: the definitive guide to measuring the extent of agreement among raters. LLC: Advanced Analytics; 2014.

Dronavalli M, Thompson SC. A systematic review of measurement tools of health and well-being for evaluating community-based interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69:805–15.

Mayer S. Examining the Relationships Between Chronic Stress, HPA Axis Activity, and Depression in a Prospective and Longitudinal Study of Medical Internship. University of Michigan; 2017. https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/137074.

Brant H, Wetherell MA, Lightman S, Crown A, Vedhara K. An exploration into physiological and self-report measures of stress in pre-registration doctors at the beginning and end of a clinical rotation. Stress. 2010;13:155–62.

Vinothkumar M, Arathi A, Joseph M, Nayana P, Jishma EJ, Sahana U. Coping, perceived stress, and job satisfaction among medical interns: The mediating effect of mindfulness. Ind Psychiatry J. 2016;25:195.

Han E, Chung E, Oh S, Woo Y, Hitchcock M. Mentoring experience and its effects on medical interns. smedj. 2014;55:593–7.

Goldacre MJ, Davidson JM, Lambert TW. Doctors’ views of their first year of medical work and postgraduate training in the UK: questionnaire surveys. Med Educ. 2003;37:802–8.

Lambert TW, Surman G, Goldacre MJ. Views of UK-trained medical graduates of 1999–2009 about their first postgraduate year of training: national surveys. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002723.

Cave J, Goldacre M, Lambert T, Woolf K, Jones A, Dacre J. Newly qualified doctors’ views about whether their medical school had trained them well: questionnaire surveys. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:38.

Goldacre MJ. Preregistration house officers’ views on whether their experience at medical school prepared them well for their jobs: national questionnaire survey. BMJ. 2003;326:1011–2.

Goldacre MJ, Davidson JM, Lambert TW. The first house officer year: views of graduate and non-graduate entrants to medical school. Med Educ. 2008;42:286–93.

Loftus TJ, Hall DJ, Malaty JZ, Kuruppacherry SB, Sarosi GA, Shaw CM, et al. Associations Between National Board Exam Performance and Residency Program Emphasis on Patient Safety and Interprofessional Teamwork. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43:581–4.

Holt KD, Miller RS, Philibert I, Heard JK, Nasca TJ. Residents’ perspectives on the learning environment: data from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education resident survey. Acad Med. 2010;85:512–8.

Roff S, McAleer S, Skinner A. Development and validation of an instrument to measure the postgraduate clinical learning and teaching educational environment for hospital-based junior doctors in the UK. Med Teach. 2005;27:326–31.

Auret K, Skinner L, Sinclair C, Evans S. Formal assessment of the educational environment experienced by interns placed in rural hospitals in Western Australia. Rural Remote Health. 13: 2549. https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/2549.

Anastasiadis C, Tsounis A, Sarafis P. The relationship between stress, social capital and quality of education among medical residents. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:274.

Gooneratne IK, Munasinghe SR, Siriwardena C, Olupeliyawa AM, Karunathilake I. Assessment of psychometric properties of a modified PHEEM questionnaire. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2008;37:993–7.

Carr SE, Celenza A, Lake F. Assessment of Junior Doctor performance: a validation study. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:129.

Carr SE, Celenza T, Lake FR. Descriptive analysis of junior doctor assessment in the first postgraduate year. Med Teach. 2014;36:983–90.

Friesen LD, Vidyarthi AR, Baron RB, Katz PP. Factors associated with intern fatigue. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(12):1981–6.

Yusoff MSB, Jie TY, Esa AR. Stress, stressors and coping strategies among house officers in a Malaysian hospital. ASEAN J Psychiatry. 2011;12:85–94.

Degen C, Weigl M, Glaser J, Li J, Angerer P. The impact of training and working conditions on junior doctors’ intention to leave clinical practice. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:119.

Appelbaum NP, Santen SA, Aboff BM, Vega R, Munoz JL, Hemphill RR. Psychological safety and support: assessing resident perceptions of the clinical learning environment. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10:651–6.

Martinez W, Etchegaray JM, Thomas EJ, Hickson GB, Lehmann LS, Schleyer AM, et al. ‘Speaking up’ about patient safety concerns and unprofessional behaviour among residents: validation of two scales. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24:671–80.

Cronin F, Clarke N, Hendrick L, Conroy R, Brugha R. The impacts of training pathways and experiences during intern year on doctor emigration from Ireland. Hum Resour Health. 2019;17:74.

Kizito S, Mukunya D, Nakitende J, Nambasa S, Nampogo A, Kalyesubula R, et al. Career intentions of final year medical students in Uganda after graduating: the burden of brain drain. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:122.

Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: a potential threat to successful health care reform. JAMA. 2011;305:2009–10.

Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Trojanowski L. The relationship between physician burnout and quality of healthcare in terms of safety and acceptability: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015141.

Hannan E, Breslin N, Doherty E, McGreal M, Moneley D, Offiah G. Burnout and stress amongst interns in Irish hospitals: contributing factors and potential solutions. Ir J Med Sci. 2018;187:301–7.

Lin KS, Zaw T, Oo WM, Soe PP. Burnout among house officers in Myanmar: a cross-sectional study. Ann Med Surg. 2018;33:7–12.

Ogero M, Akech S, Malla L, Agweyu A, Irimu G, English M, et al. Examining which clinicians provide admission hospital care in a high mortality setting and their adherence to guidelines: an observational study in 13 hospitals. Arch Dis Child. 2020;105:648–54.

World Health Organization. The 2018 update, Global Health Workforce Statistics. WHO. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.HWFGRP_0020?lang=en. Accessed 15 Sept 2020.

Benatar S. An examination of ethical aspects of migration and recruitment of health care professionals from developing countries. Clin Ethics. 2007;2:2–7.

Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, Rosales RC, Guille C, Sen S, et al. Prevalence of burnout among physicians: a systematic review. JAMA. 2018;320:1131–50.

Dubale BW, Friedman LE, Chemali Z, Denninger JW, Mehta DH, Alem A, et al. Systematic review of burnout among healthcare providers in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1247.

Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, Khan R, Guille C, Angelantonio ED, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Am Med Assoc. 2015;314:2373–83.

Gilbody SM, House AO, Sheldon TA. Routinely administered questionnaires for depression and anxiety: systematic review. BMJ. 2001;322:406–9.

Soemantri D, Herrera C, Riquelme A. Measuring the educational environment in health professions studies: a systematic review. Med Teach. 2010;32:947–52.

Ross A, Naidoo (Cyril) S, Dlamini S. An evaluation of the medical internship programme at King Edward VIII hospital, South Africa in 2016. S Afr Fam Pract. 2018;60:187–91.

Jagsi R. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s Limits on Residents’ Work Hours and Patient Safety. A Study of Resident Experiences and Perceptions Before and After Hours Reductions. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:493.

Kashner TM, Henley SS, Golden RM, Byrne JM, Keitz SA, Cannon GW, et al. Studying the effects of ACGME duty hours limits on resident satisfaction: results from VA learners’ perceptions survey. Acad Med. 2010;85:1130–9.

Acknowledgements

We thank Eli Harriss, the Knowledge Centre Manager at the Bodleian Health Care Libraries, University of Oxford, for her support in literature search.

Funding

YZ is supported by the University of Oxford Clarendon Fund Scholarship. ME is supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellowship (#207522).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YZ and ME conceived of the analysis. YZ, PM and MB contributed to study selection, data charting and collation. YZ wrote the first draft of the manuscript. ME, DG, CN, PM and MB provided critical feedback on the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

PRISMA-ScR checklist

Additional file 2:

Example search strategy in Embase

Additional file 3:

Characteristics of included studies

Additional file 4:

Detailed information of tool and questionnaire used in 92 included studies

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, Y., Musitia, P., Boga, M. et al. Tools for measuring medical internship experience: a scoping review. Hum Resour Health 19, 10 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-021-00554-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-021-00554-7