Abstract

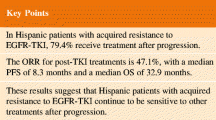

Recent advances in diagnosis and treatment are enabling a more targeted approach to treating lung cancers. Therapy targeting the specific oncogenic driver mutation could inhibit tumor progression and provide a favorable prognosis in clinical practice. Activating mutations of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) are a favorable predictive factor for EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) treatment. For lung cancer patients with EGFR-exon 19 deletions or an exon 21 Leu858Arg mutation, the standard first-line treatment is first-generation (gefitinib, erlotinib), or second-generation (afatinib) TKIs. EGFR TKIs improve response rates, time to progression, and overall survival. Unfortunately, patients with EGFR mutant lung cancer develop disease progression after a median of 10 to 14 months on EGFR TKI. Different mechanisms of acquired resistance to first-generation and second-generation EGFR TKIs have been reported. Optimal treatment for the various mechanisms of acquired resistance is not yet clearly defined, except for the T790M mutation. Repeated tissue biopsy is important to explore resistance mechanisms, but it has limitations and risks. Liquid biopsy is a valid alternative to tissue re-biopsy. Osimertinib has been approved for patients with T790M-positive NSCLC with acquired resistance to EGFR TKI. For other TKI-resistant mechanisms, combination therapy may be considered. In addition, the use of immunotherapy in lung cancer treatment has evolved rapidly. Understanding and clarifying the biology of the resistance mechanisms of EGFR-mutant NSCLC could guide future drug development, leading to more precise therapy and advances in treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the United States, an additional 224,390 new lung cancer cases were diagnosed in 2016, and accounted for about 27% of all cancer deaths [1]. Although standard platinum-based chemotherapy is the cornerstone of systemic therapy, it has a modest effect on overall survival (OS) [2]. Lung cancer is still the leading cause of cancer death worldwide [3].

In the most recent decade, treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has evolved to a great extent. The discovery of driver mutations in lung cancer allows the creation of personalized targeted treatment. It is important that lung cancer patients are tested for oncogenic drivers of cancer and receive matched targeted therapy [4]. Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR TKIs) provide a favorable treatment outcome in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation-positive patients. EGFR mutation-positive patients with lung adenocarcinoma had a response rate as high as 80%, and around 10–14 months of progression-free survival (PFS) [5, 6]. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend EGFR TKIs as first-line treatment for EGFR-mutant patients. The most common activating mutations are in-frame deletions in exon 19 and single-point mutation of exon 21 (Leu858Arg), which together account for more than 80% of known activating EGFR mutations [7, 8].

Although EGFR TKIs have a favorable and durable treatment response, most patients will eventually develop progressive disease (PD) within about one year of treatment. Furthermore, acquired resistance develops and limits the long-term efficacy of these EGFR TKIs. A variety of mechanisms of acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs have been reported. The most common mechanism is the development of acquired EGFR T790M mutation [9]. T790M was found in about 50% of EGFR–mutant cases that acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs [9]. Patients using either first- or second-generation EGFR TKIs had a similar prevalence of acquired T790M [10].

Preclinical data showed that the second-generation EGFR TKI, afatinib, could overcome the resistance caused by the T790M mutation [11], but clinical trials have not revealed the effect due to toxicity limitations. The narrow therapeutic window of afatinib caused severe adverse effects (AEs), probably owing to inhibition of wild-type EGFR [12, 13]. In the phase III LUX-Head & Neck 1 (LHN1) trial, second-line afatinib significantly improved PFS versus methotrexate in patients with recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [14]. This suggests afatinib is a drug active against wild-type EGFR. The third-generation EGFR TKI, osimertinib, has been approved for patients with T790M-positive NSCLC with acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs. Use of third-generation EGFR TKIs was related to different acquired resistance mechanisms [15,16,17,18]. Therefore, in this manuscript, we focused on these recently developed treatment strategies for EGFR-mutant NSCLC with acquired resistance to first- or second-generation EGFR TKIs.

Clinical presentation of acquired resistance to first-line EGFR TKIs

Although EGFR-mutant patients receiving EGFR TKIs have longer median PFS than those receiving platinum-based chemotherapy as first-line treatment [5, 6, 19, 20], acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs eventually emerges. In 2010, Jackman et al. proposed clinical criteria for acquired resistance to EGFR TKI based on the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) [21, 22]. Acquired resistance is defined as when EGFR-mutant NSCLC patients achieved a response or stable disease with greater than six months of targeted therapy and subsequently developed disease progression while still on the targeted agent [22]. However, the patterns of disease progression varied in clinical practice.

Oncologists traditionally change treatment regimens when there is objective evidence of radiological or clinical progression. However, in routine practice, different characteristics of disease progression might develop when using EGFR TKIs, and will confuse clinicians. Gandara et al. divided disease progression with EGFR TKIs use into three subtypes, including: oligoprogression (new sites or regrowth in a limited number of areas, maximum of four progression sites), systemic progression (multisite progression), and central nervous system (CNS) sanctuary progression (excluding leptomeningeal carcinomatosis due to the lack of effective treatment options for long-term control) [23]. For patients with CNS sanctuary progression and/or oligoprogressive disease when using a previously beneficial EGFR TKI, it may be reasonable to consider local treatment and continuation of the targeted agent. This approach yielded more than six months of additional disease control [24, 25].

Yang et al. proposed another criteria for EGFR TKI failure modes in NSCLC [26]. Based on the duration of disease control, the evolution of the tumor burden, and clinical symptoms, regardless of genotype profile, the diversity of EGFR TKI failure could be categorized into three modes, including dramatic progression, gradual progression, and local progression. The median PFS was 9.3, 12.9, and 9.2 months (p = 0.007) for these three modes, respectively, and median OS was 17.7, 39.4, and 23.1 months (p < 0.001), respectively. In patients with disease in the gradual progression mode, continuing EGFR TKI therapy was superior to switching to chemotherapy in terms of OS (39.4 vs. 17.8 months; p = 0.02) [26]. Determination of the clinical mode could favor strategies for subsequent treatment and prediction of survival.

Mechanisms of acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs

Acquired resistance mechanisms vary. Several study groups comprehensively explored the mechanisms through re-biopsy tissue specimens. The most common acquired resistance mechanisms were of three types: target gene modification, alternative pathway activation and histological or phenotypic transformation (Fig. 1).

Target gene modification

The T790M mutation, which substitutes methionine for threonine at amino acid position 790 at exon 20 of EGFR, was the most commonly acquired resistance mechanism. It accounted for about 50–60% of cases with acquired resistance to gefitinib or erlotinib [9, 10]. The 790 residue is in a key location at the entrance to a hydrophobic pocket of the ATP-binding cleft, so it is also referred to as a “gatekeeper” mutation. Because of the bulky methionine sidechain, T790M causes conformational change that leads to the development of steric hindrance and affects the ability of EGFR TKI to bind to the ATP-kinase pocket [9]. In addition, the T790M mutation of EGFR could restore the affinity of the mutant receptor for ATP, thus reducing the potency of competitive inhibitors [27].

Other second-point mutations, such as D761Y [28], T854A [29], or L747S [30], confer acquired EGFR TKI resistance, although the definite mechanism is still unclear.

Alternative pathway activation

Alternative or bypass pathway activation also causes primary resistance. Through bypass tract activation, cancer cells can survive and proliferate, even when inhibits by the initial driver pathway. The most common bypass pathway is MET amplification, which accounts for 5–10% of cases with acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs [31, 32]. MET gene amplification could activate PI3K-AKT pathway signaling independent of EGFR through driving ERBB3 dimerization and signaling [31]. However, the threshold of MET amplification that would induce TKI resistance has not been clarified. Overexpression of hepatocyte growth factor, the ligand of MET oncoprotein, also promotes EGFR TKI resistance [33].

Activation of other alternative pathways, including HER2 amplification [34], PIK3CA mutation [35], BRAF mutation, and increased expression of the receptor tyrosine kinase AXL, have been reported to promote acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs [36].

Histological and phenotypic transformation

About 5% of patients suffered from transformation from EGFR-mutant adenocarcinoma to small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) after acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs [35]. A possible theory is that the initial sample bias resulted in missing the preexisting SCLC component in the original tumor. However, the patient had a good treatment response and prolonged PFS [37], and the original activating EGFR mutations of adenocarcinoma persisted in the re-biopsy SCLC specimens [38, 39]. Recent studies disclosed that the SCLC transformation process is predisposed in adenocarcinoma by inactivation of Rb and p53 [40, 41]. In addition, evaluation of the RB1 and TP53 status of adenocarcinoma is predictive biomarker for SCLC transformation after TKI treatment [40, 41]. SCLC transformation arises from common progenitor cells of adenocarcinoma in response to EGFR TKI therapy [37].

Inappropriate induction of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) in tumor cells caused tumor invasion, metastasis, drug resistance, and stem cell properties [42, 43]. Many studies have shown that EMT is a mechanism of acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs. Different EMT transcription factors, including Slug, ZEB1, Snail, and AXL, changed with the development of acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs [42, 44]. EMT was reported in two (5%) re-biopsy tumors of 37 patients [35]. In terms of morphology, the cancer cells lost their epithelial features (e.g., E-cadherin expression) and transformed into spindle-like mesenchymal cells with a gain of vimentin [45].

Exploring the resistance mechanism of EGFR TKIs

Different mechanisms can be detected in disease progression to EGFR TKIs [46]. It is important to identify the definite tumor resistance mechanism. Repeated tumor biopsy is a key factor for the subsequent treatment plan. Genotyping, whether for the existence of EGFR T790M mutations or other oncogenic alterations, is a crucial step in guiding future treatment, according to the current NSCLC guidelines [47, 48].

However, tumor heterogeneity appears in the primary tumor and in metastatic lesions. Intratumor and inter-metastases may have diverse clones with different oncogenic driver mutations or resistance mechanisms [49]. The resistant mutations may occur at a small clone of tumor cells and clonal evolution may develop during the treatment process, so molecular-based detection methods play an important role. Mutation-enriched or ultra-sensitive (defined as an analytic sensitivity below 1%) molecular-based detection methods should be considered [46, 50]. The guideline of the College of American Pathologists, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and Association for Molecular Pathology recommends that the assay for the EGFR T790M resistant mutation is able to detect the mutation in as few as 5% of cells or less (assuming heterozygosity, a 2.5% mutant allele fraction) in clinical practice [50]. For traditional PCR-based methods, Sanger sequencing provided a sensitivity of only about 20%. Other highly sensitive PCR-based assays utilizing locked nucleic acids (LNAs) or peptide nucleic acids (PNAs) could reach 0.1–2% of analytical sensitivity [51]. Kinase fusions recently were reported as mechanisms of acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs [52]. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is becoming the preferred method because it can provide high sensitivity to detect known and unknown mutations and genetic alterations.

Sometimes, it is difficult to obtain the re-biopsy tumor specimens because of the potential risks of invasive diagnostic procedures. Prospective studies showed that the success rate of repeated biopsy was 75–95%, and serious complications were detected in about 1% of cases [32, 53, 54]. Although repeated biopsy seems safe in clinical practice, it is still limited in use because of patient fear and physician preference. Therefore, obtaining serial biopsies from the same patient is rarely feasible during the NSCLC treatment course. In addition, the existence of intra-tumor heterogeneity influences tumor evolution, metastasis and resistance mechanisms in different ways, including somatic mutations, epigenetic change and post-transcriptional modification [55,56,57]. Therefore, there may be selection bias because a single snapshot biopsy specimen is not enough to accurately represent all the resistance mechanisms of different sites.

Liquid biopsy, on the other hand, could provide a source of information on the resistance mutations of the entire tumor landscape, compared with the single site sampled using conventional tumor tissue biopsy [58]. Cell-free circulating DNA (ctDNA) is adopted for noninvasive exploration of resistance mechanisms and tumor genetic alterations. ctDNA theoretically could provide a surrogate of the whole tumor genome of both primary and metastatic lesions. Different methodologies, with high sensitivity and detection of genetic number and type alteration, are being used for ctDNA testing (Table 1) [59]. The EGFR T790M mutation could be detected in plasma samples by highly sensitive genotyping methods, including next-generation sequencing, droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR), and bead, emulsion, amplification and magnetics (BEAMing) assays [60,61,62,63]. The FDA has approved the Roche real-time PCR assay, cobas® EGFR Mutation Test v2, for detection of EGFR mutations in ctDNA in blood samples. Using ctDNA to detect mutations can produce a high positive predictive value. But, not all tumors shed ctDNA to the same degree, because of differences in tumor size, stage, location, vascularity, sites of metastatic disease and treatment history [64, 65]. Several studies found that up to 35% of patients with EGFR T790M might have false-negative plasma levels, compared with tissue biopsy [66, 67]. Therefore, if liquid biopsy shows a negative EGFR T790M mutation, tissue biopsy for confirmation is necessary [66].

Serial analysis of ctDNA can track the molecular dynamic evolution of the tumor and monitor treatment response. However, the technological approach is not standardized because of the broad range of ctDNA isolation techniques, DNA analysis and quantification [65, 68].

The management of progression during EGFR TKIs use

According to the NCCN guideline [48], subsequent therapy after progression with first-line EGFR TKIs includes different treatment recommendations, which have been plotted as an algorithm. For patients with sensitizing EGFR mutations who progress during or after first-line targeted therapy, recommended therapy depends on the acquired resistance mechanism and whether the progression is asymptomatic or symptomatic.

We modified the latest NCCN and ESMO Guidelines [48, 69], and included the feasibility of liquid biopsy based on the emerging evidence from studies and trials [70,71,72,73]. An algorithm was proposed (Fig. 2) to provide clinical physicians with an appropriate practice plan for patients who experience disease progression on EGFR TKIs.

TKI beyond progression

In clinical practice, clinicians may prescribe EGFR TKI therapy beyond progression, especially when patients suffer from asymptomatic progression. Nishie et al. retrospectively analyzed Japanese patients with EGFR mutations. Continuous use of EGFR TKIs beyond progression in patients with activating EGFR mutations may prolong OS compared with switching to cytotoxic chemotherapy [74]. In addition, the phase II ASPIRATION study demonstrated that continued erlotinib therapy following progression is feasible in selected patients [75]. The NCCN Panel recommended continuing EGFR TKIs, whether erlotinib, gefitinib, or afatinib, and considering local therapy in patients with asymptomatic progression [48].

A flare-up phenomenon (rapid disease progression) occasionally is noted after discontinuation of EGFR TKIs. Intratumor heterogeneity is the possible mechanism of the phenomenon. Compared to the resistant clone with indolent behavior, rapid regrowth of TKI-sensitive clones causes rapid clinical deterioration when EGFR TKIs are discontinued [76]. One retrospective study also showed that 14 of 61 (23%) patients suffered from disease flare after stopping EGFR TKIs [77]. Therefore, some patients were prescribed EGFR TKIs after acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs.

The phase III IMPRESS trial aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of continuing gefitinib combined with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in patients with EGFR-mutation-positive advanced NSCLC with acquired resistance to first-line gefitinib. A total of 265 patients were enrolled. However, continuation of gefitinib after disease progression on first-line gefitinib did not prolong PFS in patients treated with platinum-based doublet chemotherapy as subsequent treatment. A long-term follow-up found that median OS was 13.4 months in the combination arm and 19.5 months in the control arm (HR 1.44; p = 0.016) [78]. Besides, the gefitinib group had more side effects and grade 3 or worse AEs. According to the results of the IMPRESS trial, continuation of chemotherapy with first-generation EGFR TKIs after acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs is not considered as standard treatment.

Switch therapy

Repeated biopsy could provide information about the mechanism of acquired resistance. If there is no targetable oncogenic driver mutations/bypass pathways and corresponding target medications, chemotherapy is still the standard subsequent treatment after acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs. The NCCN guideline offers a treatment algorithm for patients whose disease has progressed on first-line EGFR TKIs. Platinum doublet with or without bevacizumab chemotherapy should be considered and recommended as second-line treatment for patients when they suffer from systemic progression due to acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs.

Two retrospective studies found that for EGFR-mutant patients who received platinum-based chemotherapy after disease progression with first-line EGFR TKI treatment, the response rates were 14–18%. Their median PFS with second-line chemotherapy was about four months [79, 80]. Because EGFR mutations are detected mostly in patients with an adenocarcinoma or non-squamous histology, the optimum regimen might be pemetrexed and platinum combination treatment [81], followed by maintenance pemetrexed for patients who did not suffer from disease progression [48, 82].

The most common mechanism of acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs is acquired T790M mutation. Second-generation EGFR TKIs, including afatinib, dacomitinib and neratinib, had efficacy in inhibiting proliferation of T790M mutation-positive cells in vitro. However, clinical trials showed disappointing results due to high toxicities resulting from the narrow therapeutic window. In contrast to second-generation EGFR TKIs, third-generation EGFR TKIs had a good treatment effect on tumors harboring EGFR T790M mutations [48, 83,84,85].

Next-generation (third-generation) epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases inhibitors (EGFR TKIs)

The third-generation EGFR TKIs can form an irreversible covalent binding to EGFR. They are pyrimidine-based compounds, and differ from quinazolines-based first-and second-generation EGFR TKIs (Table 2) [86]. Third-generation EGFR TKIs can attenuate EGFR T790M activity and have less epithelial toxicity due to less wild-type EGFR activity [86, 87]. Among them, osimertinib (AZD9291) received FDA and European Medicines Agency (EMA) approval in November 2015 and February 2016, respectively, for treatment of patients with T790M mutation-positive NSCLC after acquired resistance to first-line EGFR TKIs treatment. Table 3 shows the available efficacy data of different third-generation EGFR TKIs in clinical trials.

-

Osimertinib (AZD9291)

Osimertinib (AstraZeneca, Macclesfield, UK) is an irreversible mono-anilino-pyrimidine EGFR TKI that covalently binds to the ATP-binding site, CYS797, of the EGFR tyrosine kinase domain. In EGFR recombinant enzyme assays, osimertinib showed potent activity against diverse activating EGFR mutations with/without T790M. According to the preclinical data, osimertinib has 200 times greater potency against L858R/T790M than wild-type EGFR [88]. Two circulating metabolites of osimertinib, AZ5104 and AZ7550, were detected, and both had comparable potency to sensitizing EGFR mutation and T790M [89]. There was no significant difference in pharmacokinetic exposure between Asian and non-Asian patients, showing a minimal food effect [90]. In addition, unlike first- and second-generation EGFR TKIs, osimertinib exposure was not affected by concurrent administration of omeprazole [91].

AURA (NCT01802632) is a phase I/II dose-escalation clinical trial of osimertinib, which enrolled 253 Asian and western NSCLC patients with acquired resistance to first- or second-generation EGFR TKIs, as defined by Jackman criteria [22, 92]. Patients were not preselected according to T790M status [92]. Thirty-one patients were treated across five dose-escalation cohorts (20, 40, 80, 160 and 240 mg oral, daily) and 222 were treated in the dose-expansion cohort.

In the dose-escalation cohort, there was no dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) and the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) has not been reached. Of the 239 evaluable patients, the objective response rate (ORR) was 51% and the disease control rate (DCR) was 84%. Patients with EGFR-T790M mutation had a better ORR (61% vs. 21%), DCR (95% vs. 61%), and longer median PFS (9.6 months vs. 2.8 months) than patients without an EGFR-T790M mutation. The drug is relatively safe, and most of the AEs were grade 1 and 2. The most common AEs were diarrhea (47%), skin toxicity (40%), nausea (22%), and anorexia (21%). When patients took higher dose levels (160 and 240 mg), there was an increasing incidence and severity of AEs (rash, dry skin, and diarrhea). Based on efficacy and safety, 80 mg daily was selected as the recommended dose for further clinical trials [92].

Then, a phase II “AURA2” study (NCT02094261) was initiated to enroll NSCLC patients with an EGFR-T790M mutation and acquired resistance to approved EGFR TKIs; the enrollment criteria were similar to those of the AURA study extension cohort. A preplanned pooled analysis was performed, including 201 patients from the 80 mg osimertinib expansion cohort of AURA and 210 patients from AURA2; ORR was 66%, DCR was 91%, and median PFS was 11.0 months [93].

In the phase III AURA3 study, 419 patients were randomized into osimertinib or platinum-pemetrexed chemotherapy (maintenance pemetrexed was allowed) groups after they had acquired resistance to first-line EGFR TKI therapy. The investigator-assessed PFS (primary endpoint) was significantly longer in the osimertinib arm than in the chemotherapy arm (median 10.1 vs. 4.4 months; HR 0.30; p < 0.001). The FDA has granted regular approval to the third-generation EGFR TKI, osimertinib, for the treatment of patients with metastatic EGFR T790M mutation-positive NSCLC.

In the preclinical study, osimertinib demonstrated greater penetration of the mouse blood-brain barrier than gefitinib, rociletinib, or afatinib [94]. There were several reports of dramatic intracranial response to osimertinib in patients with EGFR T790M lung cancer [94, 95]. A phase I study (BLOOM, NCT02228369), which has enrolled pretreated EGFR-mutant NSCLC patients with leptomeningeal metastasis treated with 160 mg osimertinib once daily, is ongoing. The preliminary data is promising [96].

-

Rociletinib (CO-1686)

Rociletinib, a 2,4-disubstituted pyrimidine compound, is an oral, irreversible, mutant-selective inhibitor of activating EGFR mutations, including T790M, and spares wild-type EGFR [97]. TIGER-X (NCT01526928A), a phase I/II trial of rociletinib, enrolled 130 EGFR-mutant NSCLC patients with acquired resistance to first- or second-generation EGFR TKIs [83]. The ORR was 59% for the 46 evaluable T790M mutation-positive patients and 29% for the 17 T790M mutation-negative patients [83]. Because of targeting of IGF-1R, hyperglycemia (22%) was detected as the most common grade 3 AE. An independent updated analysis of the TIGER-X trial showed that the T790M mutation-positive patients had an ORR of 45% [98]. In addition, a series of cases with response to osimertinib after resistance to rociletinib were reported [99]. Clovis Oncology, Inc. decided to stop enrollment in all ongoing rociletinib studies and terminate the future development program in May 2016.

-

Olmutinib (BI-1482694/HM61713; Olita™)

A phase I/II dose escalation clinical trial, HM-EMSI-101 (NCT01588145), was initiated in South Korea [100]. Patients took olmutinib in doses ranging from 75 to 1200 mg/day. Among the 34 patients with NSCLC harboring T790M detected by a central laboratory, the ORR was 58.8%. The DCR was 97.1% for patients treated with olmutinib in doses greater than 650 mg. The most common DLTs involved gastrointestinal symptoms, abnormal liver function (AST/ALT), and increasing amylase/lipase levels. Therefore, 800 mg/day was selected as the recommended phase II dose. Seventy-six patients with centrally confirmed T790M mutation-positive NSCLC were enrolled in part II of the study, and 70 were evaluable for response. The ORR was 61% and median PFS was 6.9 months [101]. Based on the aforementioned result, olmutinib was first approved in South Korea in 2016. However, Boehringer Ingelheim decided to stop the co-development of this drug because of an unexpected grade 3/4 skin toxicity (including palmoplantar keratoderma) [102].

-

ASP8273

Preclinical data showed ASP8273 had antitumor activity against EGFR TKI-resistant cells, including those with resistance to osimertinib and rociletinib [103]. A multi-cohort, phase 1 study (NCT02113813) was initiated to evaluate the safety and efficacy of ASP8273 in NSCLC patients with disease progression after EGFR TKI treatment. The most common AEs included diarrhea (47%), nausea (42%), and fatigue (32%). The most common grade 3/4 AE was hyponatremia (17%). Across all doses, the ORR was 30.7%, and median PFS was 6.8 months in patients with EGFR T790M [104]. A phase III randomized clinical trial (SOLAR) was conducted to compare the efficacy and safety of ASP8273 with that of erlotinib or gefitinib as first-line treatment for advanced EGFR-mutant NSCLC (NCT02588261). However, Astellas Pharma (OTCPK: ALPMY) terminated the phase III SOLAR study in May 2017 because the treatment advantage apparently was not adequate enough to justify continuation.

-

Nazartinib (EGF816)

A phase I/II first-in-human study, NCT02108964 (EGF816X2101), investigated nazartinib in EGFR-mutant patients. A total of 152 patients were treated across seven cohorts using doses ranging from 75 to 350 mg [105]. Among the 147 evaluable patients, the ORR and DCR were 46.9% and 87.1%, respectively. The median PFS across all dose cohorts was 9.7 months. Skin rash (54%), diarrhea (37%), and pruritus (34%) were the most common AEs. The skin rashes related to nazartinib were different from those caused by other EGFR TKIs in pattern, location, and histology. The most common grade 3/4 AE was diarrhea (16%) [105]. A phase II clinical trial with six cohorts is ongoing. In addition, a phase Ib/II trial (NCT02335944 and NCT02323126) is ongoing to investigate the efficacy of combined treatments with INC280, a specific MET inhibitor, and with nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody in patients with EGFR-T790M mutation after acquired resistance to first-line EGFR TKI.

-

AC0010

A phase I/II, first-in-human dose-escalation and expansion phase clinical trial (NCT02330367) was carried out with advanced NSCLC patients with acquired T790M mutation after first-generation EGFR TKIs treatment [106]. In all, 136 patients have been treated across seven cohorts (50, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300, and 350 mg BID), and MTD has not been reached. The most common drug-related AEs were diarrhea (38%), rash (26%) and ALT/AST elevation. Grade 3/4 AEs of diarrhea (2%), rash (2%) and ALT/AST elevation (4%, 2%) were recorded. The 124 evaluable patients had ORR and DCR of 44% and 85%, respectively. Because of the drug safety profile and activity against NSCLC with acquired T790M mutation, a phase II, AEGIS-1 study is ongoing to evaluate treatment efficacy for patients with T790M mutation-positive NSCLC with acquired resistance to first-generation EGFR TKIs. An open label, randomized phase III trial (NCT03058094) also is ongoing to compare AC0010 (300 mg, BID) with pemetrexed/cisplatin (4–6 cycles) in patients with advanced NSCLC who have progressed following prior therapy with EGFR TKI. T790M in biopsy samples was confirmed by a central laboratory.

-

HS-10296

An open-label, multicenter, phase I/II dose escalation and expansion trial (NCT02981108) is currently recruiting patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC after acquired resistance to first- and/or second-generation EGFR TKIs.

-

PF-06747775

PF-06747775 has potent antitumor efficacy against NSCLC harboring a classical mutation with/without T790M. It significantly attenuates T790M activity and has less toxicity because of the reduction of proteome reactivity relative to earlier EGFR TKIs [107, 108]. A phase I/II clinical trial (NCT02349633) involving patients with advanced NSCLC harboring EGFR mutations (Del19 or L858R with/without T790M) is ongoing.

Combination therapy

-

Vertical pathway

Cetuximab is a recombinant human/mouse chimeric EGFR IgG1 monoclonal antibody. Combining afatinib and cetuximab may be useful for patients who have progressed after receiving EGFR TKI therapy and chemotherapy [109]. Among 126 patients, the response rate of patients with T790M-positive and T790M-negative tumors was comparable (32% vs. 25%; p = .341). The two groups showed no statistical difference in PFS. The NCCN Panel recommends considering an afatinib/cetuximab regimen for patients who have progressed after receiving EGFR TKIs and chemotherapy [48]. However, skin rash (90% all grades) and diarrhea (71% all grades) were the two most common adverse effects. Grades 3 and 4 adverse effects were 44% and 2%, respectively. Because of the high rate of AEs with this combination therapy, it is no longer a preferred treatment for patients with tumor harboring EGFR T790M mutations [110].

-

Horizontal pathway

Since bypass signaling pathway activation is an important acquired resistance mechanism of EGFR TKIs, it is reasonable to combine inhibition of EGFR pathway signaling and inhibitors for the bypass signaling pathway to overcome resistance. Different horizontal combination strategies are being investigated, but results are preliminary and immature (Table 4).

MET amplification is an important mechanism of acquired resistance to EGFR TKI therapy [31, 111]. A randomized, open-label, phase 2 study enrolled patients with advanced NSCLC (enriched for EGFR-mutant disease) who developed acquired resistance to erlotinib to receive emibetuzumab (LY2875358), a humanized IgG4 monoclonal bivalent MET antibody, with or without erlotinib therapy. The ORR of patients whose re-biopsy samples harbored MET overexpression (≥60%) was 3.8% in the combination arm and 4.8% in the monotherapy arm [112]. In Japan, another phase II clinical trial enrolled 45 patients with advanced EGFR-mutant NSCLC who developed acquired resistance to first-generation EGFR TKIs to receive tivantinib (ARQ197) and erlotinib combination therapy. The response rate was 6.7%. High MET expression (≥ 50%) was detected by immunohistochemical stain in 48.9% of the patients, including all three partial responders [113]. In addition, a combination of capmatinib (INC280) and gefitinib was tested in a phase 2 study (NCT01610336) in EGFR-mutant NSCLC patients after acquired resistance to gefitinib. EGFR T790M NSCLCs were excluded and high cMET expression was required. Of the 65 evaluable patients, the ORR was 18% and DCR was 80%. More responses were seen in tumors with MET amplifications [114].

In addition to MET amplification, different medications are being investigated to inhibit other bypass signaling pathways, including a heat shock protein 90 inhibitor, AUY922 (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01259089 and NCT01646125); a JAK inhibitor, ruxolitinib (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02155465 and NCT02145637); a MET/AXL/FGFR inhibitor S- 49076 (EU Clinical Trials Register: EudraCT Number: 2015–002646-31) and a PI3K inhibitor, buparlisib (BKM120) (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01570296 and NCT01487265).

Furthermore, combination therapy with osimertinib has been investigated. The TATTON study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02143466) enrolled patients who received osimertinib-based combination therapy with either a MET inhibitor (savolitinib), MEK inhibitor (selumetinib), or anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody (durvalumab) [115]. However, the rate of drug-related interstitial disease was high in the osimertinib plus durvalumab arm, so the development of this combination therapy was discontinued [116]. Other clinical trials, including osimertinib in combination with ramucirumab, necitumumab, bevacizumab, or navitoclax (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02789345, 02496663, 02803203 and 02520778), are ongoing.

Combination therapies have higher rates of toxicities and side effects than a single agent does. Although the aforementioned medications have been evaluated in clinical trials, clinicians should keep in mind the possibility of AEs when prescribing combination therapy.

Immunotherapy

For subsequent therapy, or immunotherapy, nivolumab and pembrolizumab have been approved as standard treatment, and high-level PD-L1 expression in tumors can predict a higher response rate. Phase III trials assessing pembrolizumab, nivolumab, or atezolizumab compared to docetaxel as subsequent therapy for patients with metastatic NSCLC found there were no survival benefits for EGFR-mutant lung cancer patients. Also, there were not enough patients with these mutations to determine whether there were statistically significant differences. However, immunotherapy was comparable to chemotherapy and was better tolerated. [117,118,119]. Until now, there is not enough evidence to recommend pembrolizumab, nivolumab, or atezolizumab as subsequent therapy for EGFR-mutant patients.

In vitro, EGFR-mutant lung cancer cells inhibited antitumor immunity by activating the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway to suppress T-cell function [120]. This finding indicates that EGFR functions as an oncogene through cell-autonomous mechanisms and raises the possibility that other oncogenes may drive immune escape [120]. However, retrospective studies showed that NSCLCs harboring EGFR mutations were associated with low response rates to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, which may have resulted from low rates of concurrent PD-L1 expression and CD8(+) TILs within the tumor microenvironment [119]. A retrospective study on the efficacy of nivolumab in patients with EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC after EGFR TKI failure found that T790M-negative patients were more likely than T790M-positive patients to benefit from nivolumab [121].

Different phase 1 trials combining EGFR TKIs with immunotherapies include nivolumab (ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01454102); pembrolizumab (ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT02039674); and atezolizumab (ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT02013219). These studies are all ongoing.

Conclusions

EGFR TKIs are currently the standard first-line treatment of patients with advanced NSCLC harboring activating EGFR mutations. After acquiring resistance to first-line EGFR TKI therapy, it is important that the mechanisms of acquired resistance in all patients are explored. Then, based on the mechanism, subsequent treatment can be chosen. Continuation of EGFR TKI therapy is suitable for select patients with asymptomatic progression and/or oligoprogression. Repeat tumor biopsy to detect the EGFR T790M mutation is the current standard of care, and osimertinib has been approved for patients with acquired EGFR T790M-mutant disease. Liquid biopsy is an alternative method to detect plasma EGFR T790M mutation and to identify patients suitable for osimertinib therapy. Combination therapy may be effective for acquired resistance resulting from activation of the bypass signaling pathway. Advances in the detection method for different resistance mechanisms and the development of new drugs are both urgently needed for personalized therapy.

Abbreviations

- 95% CI:

-

95% confidence interval

- AEs:

-

adverse effects

- ASCO:

-

American Society of Clinical Oncology

- ctDNA:

-

circulating tumor DNA

- DLT:

-

dose-limiting toxicity

- EGFR:

-

epidermal growth factor receptor

- EMT:

-

epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- ESMO:

-

European Society for Medical Oncology

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- MLT:

-

maximum tolerated dose

- NCCN:

-

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- NSCLC:

-

non-small cell lung cancer

- ORR:

-

objective response rate, DCR disease control rate

- OS:

-

overall survival

- PD:

-

progressive disease

- PFS:

-

progression-free survival

- SCLC:

-

small cell lung cancer

- TKI:

-

tyrosine kinase inhibitor

References

Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Kramer JL, Rowland JH, Stein KD, Alteri R, Jemal A. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:271–89.

Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, Langer C, Sandler A, Krook J, Zhu J, Johnson DH, Eastern Cooperative Oncology G. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:92–8.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30.

Kris MG, Johnson BE, Berry LD, Kwiatkowski DJ, Iafrate AJ, Wistuba II, Varella-Garcia M, Franklin WA, Aronson SL, Su PF, et al. Using multiplexed assays of oncogenic drivers in lung cancers to select targeted drugs. JAMA. 2014;311:1998–2006.

Mok TS, Wu Y-L, Thongprasert S, Yang C-H, Chu D-T, Saijo N, Sunpaweravong P, Han B, Margono B, Ichinose Y, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin–paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:947–57.

Wu YL, Zhou C, Hu CP, Feng J, Lu S, Huang Y, Li W, Hou M, Shi JH, Lee KY, et al. Afatinib versus cisplatin plus gemcitabine for first-line treatment of Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring EGFR mutations (LUX-lung 6): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:213–22.

Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, Harris PL, Haserlat SM, Supko JG, Haluska FG, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–39.

Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC, Tracy S, Greulich H, Gabriel S, Herman P, Kaye FJ, Lindeman N, Boggon TJ, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–500.

Kobayashi S, Boggon TJ, Dayaram T, Janne PA, Kocher O, Meyerson M, Johnson BE, Eck MJ, Tenen DG, Halmos B. EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:786–92.

Wu SG, Liu YN, Tsai MF, Chang YL, Yu CJ, Yang PC, Yang JC, Wen YF, Shih JY. The mechanism of acquired resistance to irreversible EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor-afatinib in lung adenocarcinoma patients. Oncotarget. 2016;7:12404–13.

Kwak EL, Sordella R, Bell DW, Godin-Heymann N, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, Harris PL, Driscoll DR, Fidias P, Lynch TJ, et al. Irreversible inhibitors of the EGF receptor may circumvent acquired resistance to gefitinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7665–70.

Yap TA, Vidal L, Adam J, Stephens P, Spicer J, Shaw H, Ang J, Temple G, Bell S, Shahidi M, et al. Phase I trial of the irreversible EGFR and HER2 kinase inhibitor BIBW 2992 in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3965–72.

Li D, Ambrogio L, Shimamura T, Kubo S, Takahashi M, Chirieac LR, Padera RF, Shapiro GI, Baum A, Himmelsbach F, et al. BIBW2992, an irreversible EGFR/HER2 inhibitor highly effective in preclinical lung cancer models. Oncogene. 2008;27:4702–11.

Machiels JP, Haddad RI, Fayette J, Licitra LF, Tahara M, Vermorken JB, Clement PM, Gauler T, Cupissol D, Grau JJ, et al. Afatinib versus methotrexate as second-line treatment in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck progressing on or after platinum-based therapy (LUX-Head & Neck 1): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:583–94.

Niederst MJ, Hu H, Mulvey HE, Lockerman EL, Garcia AR, Piotrowska Z, Sequist LV, Engelman JA. The allelic context of the C797S mutation acquired upon treatment with third-generation EGFR inhibitors impacts sensitivity to subsequent treatment strategies. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:3924–33.

Piotrowska Z, Thress KS, Mooradian M, Heist RS, Azzoli CG, Temel JS, Rizzo C, Nagy RJ, Lanman RB, Gettinger SN, et al. MET amplification (amp) as a resistance mechanism to osimertinib. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:9020–9020.

Yu HA, Tian SK, Drilon AE, Borsu L, Riely GJ, Arcila ME, Ladanyi M. Acquired resistance of EGFR-mutant lung cancer to a T790M-specific EGFR inhibitor: emergence of a third mutation (C797S) in the EGFR tyrosine kinase domain. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:982–4.

Song HN, Jung KS, Yoo KH, Cho J, Lee JY, Lim SH, Kim HS, Sun JM, Lee SH, Ahn JS, et al. Acquired C797S mutation upon treatment with a T790M-specific third-generation EGFR inhibitor (HM61713) in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:e45–7.

Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, Tan EH, Hirsh V, Thongprasert S, Campos D, Maoleekoonpiroj S, Smylie M, Martins R, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–32.

Sequist LV, Yang JC-H, Yamamoto N, O'Byrne K, Hirsh V, Mok T, Geater SL, Orlov S, Tsai C-M, Boyer M, et al. Phase III study of Afatinib or cisplatin plus Pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3327–34.

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–47.

Jackman D, Pao W, Riely GJ, Engelman JA, Kris MG, Janne PA, Lynch T, Johnson BE, Miller VA. Clinical definition of acquired resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:357–60.

Gandara DR, Li T, Lara PN, Kelly K, Riess JW, Redman MW, Mack PC. Acquired resistance to targeted therapies against oncogene-driven non–small-cell lung cancer: approach to subtyping progressive disease and clinical implications. Clinical Lung Cancer. 15:1–6.

Shukuya T, Takahashi T, Naito T, Kaira R, Ono A, Nakamura Y, Tsuya A, Kenmotsu H, Murakami H, Harada H, et al. Continuous EGFR-TKI administration following radiotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer patients with isolated CNS failure. Lung Cancer. 2011;74:457–61.

Weickhardt AJ, Scheier B, Burke JM, Gan G, Lu X, Bunn PA Jr, Aisner DL, Gaspar LE, Kavanagh BD, Doebele RC, Camidge DR. Local ablative therapy of Oligoprogressive disease prolongs disease control by tyrosine kinase inhibitors in oncogene-addicted non–small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 7:1807–14.

Yang J-J, Chen H-J, Yan H-H, Zhang X-C, Zhou Q, Su J, Wang Z, Xu C-R, Huang Y-S, Wang B-C, et al. Clinical modes of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor failure and subsequent management in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2013;79:33–9.

Yun CH, Mengwasser KE, Toms AV, Woo MS, Greulich H, Wong KK, Meyerson M, Eck MJ. The T790M mutation in EGFR kinase causes drug resistance by increasing the affinity for ATP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2070–5.

Balak MN, Gong Y, Riely GJ, Somwar R, Li AR, Zakowski MF, Chiang A, Yang G, Ouerfelli O, Kris MG, et al. Novel D761Y and common secondary T790M mutations in epidermal growth factor receptor-mutant lung adenocarcinomas with acquired resistance to kinase inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6494–501.

Bean J, Riely GJ, Balak M, Marks JL, Ladanyi M, Miller VA, Pao W. Acquired resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor kinase inhibitors associated with a novel T854A mutation in a patient with EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7519–25.

Yamaguchi F, Fukuchi K, Yamazaki Y, Takayasu H, Tazawa S, Tateno H, Kato E, Wakabayashi A, Fujimori M, Iwasaki T, et al. Acquired resistance L747S mutation in an epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor-naive patient: a report of three cases. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:357–60.

Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, Song Y, Hyland C, Park JO, Lindeman N, Gale CM, Zhao X, Christensen J, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316:1039–43.

Yu HA, Arcila ME, Rekhtman N, Sima CS, Zakowski MF, Pao W, Kris MG, Miller VA, Ladanyi M, Riely GJ. Analysis of tumor specimens at the time of acquired resistance to EGFR-TKI therapy in 155 patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:2240–7.

Fan W, Tang Z, Yin L, Morrison B, Hafez-Khayyata S, Fu P, Huang H, Bagai R, Jiang S, Kresak A, et al. MET-independent lung cancer cells evading EGFR kinase inhibitors are therapeutically susceptible to BH3 mimetic agents. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4494–505.

Takezawa K, Pirazzoli V, Arcila ME, Nebhan CA, Song X, de Stanchina E, Ohashi K, Janjigian YY, Spitzler PJ, Melnick MA, et al. HER2 amplification: a potential mechanism of acquired resistance to EGFR inhibition in EGFR-mutant lung cancers that lack the second-site EGFRT790M mutation. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:922–33.

Sequist LV, Waltman BA, Dias-Santagata D, Digumarthy S, Turke AB, Fidias P, Bergethon K, Shaw AT, Gettinger S, Cosper AK, et al. Genotypic and histological evolution of lung cancers acquiring resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:75ra26.

Zhang Z, Lee JC, Lin L, Olivas V, Au V, LaFramboise T, Abdel-Rahman M, Wang X, Levine AD, Rho JK, et al. Activation of the AXL kinase causes resistance to EGFR-targeted therapy in lung cancer. Nat Genet. 2012;44:852–60.

Oser MG, Niederst MJ, Sequist LV, Engelman JA. Transformation from non-small-cell lung cancer to small-cell lung cancer: molecular drivers and cells of origin. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:e165–72.

Zakowski MF, Ladanyi M, Kris MG, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center lung cancer OncoGenome G. EGFR mutations in small-cell lung cancers in patients who have never smoked. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:213–5.

Alam N, Gustafson KS, Ladanyi M, Zakowski MF, Kapoor A, Truskinovsky AM, Dudek AZ. Small-cell carcinoma with an epidermal growth factor receptor mutation in a never-smoker with gefitinib-responsive adenocarcinoma of the lung. Clin Lung Cancer. 2010;11:E1–4.

Lee JK, Lee J, Kim S, Kim S, Youk J, Park S, An Y, Keam B, Kim DW, Heo DS, et al. Clonal history and genetic predictors of transformation into small-cell carcinomas from lung adenocarcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3065–74.

Niederst MJ, Sequist LV, Poirier JT, Mermel CH, Lockerman EL, Garcia AR, Katayama R, Costa C, Ross KN, Moran T, et al. RB loss in resistant EGFR mutant lung adenocarcinomas that transform to small-cell lung cancer. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6377.

Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–90.

Nurwidya F, Takahashi F, Murakami A, Takahashi K. Epithelial mesenchymal transition in drug resistance and metastasis of lung cancer. Cancer Res Treat. 2012;44:151–6.

Chang TH, Tsai MF, Su KY, Wu SG, Huang CP, Yu SL, Yu YL, Lan CC, Yang CH, Lin SB, et al. Slug confers resistance to the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1071–9.

Suda K, Tomizawa K, Fujii M, Murakami H, Osada H, Maehara Y, Yatabe Y, Sekido Y, Mitsudomi T. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition in an epidermal growth factor receptor-mutant lung cancer cell line with acquired resistance to erlotinib. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:1152–61.

Belchis DA, Tseng LH, Gniadek T, Haley L, Lokhandwala P, Illei P, Gocke CD, Forde P, Brahmer J, Askin FB, et al. Heterogeneity of resistance mutations detectable by nextgeneration sequencing in TKI-treated lung adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:45237–48.

Novello S, Barlesi F, Califano R, Cufer T, Ekman S, Levra MG, Kerr K, Popat S, Reck M, Senan S, et al. Metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:v1–v27.

Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aisner DL, Akerley W, Bauman J, Chirieac LR, D'Amico TA, DeCamp MM, Dilling TJ, Dobelbower M, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer, version 5.2017, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2017;15:504–35.

Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, Math M, Larkin J, Endesfelder D, Gronroos E, Martinez P, Matthews N, Stewart A, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:883–92.

Lindeman NI, Cagle PT, Beasley MB, Chitale DA, Dacic S, Giaccone G, Jenkins RB, Kwiatkowski DJ, Saldivar JS, Squire J, et al. Molecular testing guideline for selection of lung cancer patients for EGFR and ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors: guideline from the College of American Pathologists, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and Association for Molecular Pathology. J Mol Diagn. 2013;15:415–53.

Kim HR, Lee SY, Hyun DS, Lee MK, Lee HK, Choi CM, Yang SH, Kim YC, Lee YC, Kim SY, et al. Detection of EGFR mutations in circulating free DNA by PNA-mediated PCR clamping. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2013;32:50.

Ou SI, Horn L, Cruz M, Vafai D, Lovly CM, Spradlin A, Williamson MJ, Dagogo-Jack I, Johnson A, Miller VA, et al. Emergence of FGFR3-TACC3 fusions as a potential by-pass resistance mechanism to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in EGFR mutated NSCLC patients. Lung Cancer. 2017;111:61–4.

Chouaid C, Dujon C, Do P, Monnet I, Madroszyk A, Le Caer H, Auliac JB, Berard H, Thomas P, Lena H, et al. Feasibility and clinical impact of re-biopsy in advanced non small-cell lung cancer: a prospective multicenter study in a real-world setting (GFPC study 12-01). Lung Cancer. 2014;86:170–3.

Liao BC, Bai YY, Lee JH, Lin CC, Lin SY, Lee YF, Ho CC, Shih JY, Chang YC, Yu CJ, et al. Outcomes of research biopsies in clinical trials of EGFR mutation-positive non-small cell lung cancer patients pretreated with EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors. J Formos Med Assoc. 2017;

Caswell DR, Swanton C. The role of tumour heterogeneity and clonal cooperativity in metastasis, immune evasion and clinical outcome. BMC Med. 2017;15:133.

Jamal-Hanjani M, Wilson GA, McGranahan N, Birkbak NJ, Watkins TBK, Veeriah S, Shafi S, Johnson DH, Mitter R, Rosenthal R, et al. Tracking the evolution of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2109–21.

Abbosh C, Birkbak NJ, Wilson GA, Jamal-Hanjani M, Constantin T, Salari R, Le Quesne J, Moore DA, Veeriah S, Rosenthal R, et al. Phylogenetic ctDNA analysis depicts early-stage lung cancer evolution. Nature. 2017;545:446–51.

Khoo C, Rogers TM, Fellowes A, Bell A, Fox S. Molecular methods for somatic mutation testing in lung adenocarcinoma: EGFR and beyond. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:126–41.

Huang WL, Chen YL, Yang SC, Ho CL, Wei F, Wong DT, Su WC, Lin CC. Liquid biopsy genotyping in lung cancer: ready for clinical utility? Oncotarget. 2017;8:18590–608.

Santarpia M, Karachaliou N, Gonzalez-Cao M, Altavilla G, Giovannetti E, Rosell R. Feasibility of cell-free circulating tumor DNA testing for lung cancer. Biomark Med. 2016;10:417–30.

Taniguchi K, Uchida J, Nishino K, Kumagai T, Okuyama T, Okami J, Higashiyama M, Kodama K, Imamura F, Kato K. Quantitative detection of EGFR mutations in circulating tumor DNA derived from lung adenocarcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:7808–15.

Oxnard GR, Paweletz CP, Kuang Y, Mach SL, O'Connell A, Messineo MM, Luke JJ, Butaney M, Kirschmeier P, Jackman DM, Janne PA. Noninvasive detection of response and resistance in EGFR-mutant lung cancer using quantitative next-generation genotyping of cell-free plasma DNA. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:1698–705.

Sundaresan TK, Sequist LV, Heymach JV, Riely GJ, Janne PA, Koch WH, Sullivan JP, Fox DB, Maher R, Muzikansky A, et al. Detection of T790M, the acquired resistance EGFR mutation, by tumor biopsy versus noninvasive blood-based analyses. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:1103–10.

Escriu C, Field JK. Circulating tumour DNA and resistance mechanisms during EGFR inhibitor therapy in lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8:2357–9.

Ignatiadis M, Lee M, Jeffrey SS. Circulating tumor cells and circulating tumor DNA: challenges and opportunities on the path to clinical utility. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:4786–800.

Oxnard GR, Thress KS, Alden RS, Lawrance R, Paweletz CP, Cantarini M, Yang JC, Barrett JC, Janne PA. Association between plasma genotyping and outcomes of treatment with Osimertinib (AZD9291) in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3375–82.

Takahama T, Sakai K, Takeda M, Azuma K, Hida T, Hirabayashi M, Oguri T, Tanaka H, Ebi N, Sawa T, et al. Detection of the T790M mutation of EGFR in plasma of advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients with acquired resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (West Japan oncology group 8014LTR study). Oncotarget. 2016;7:58492–9.

Bordi P, Del Re M, Danesi R, Tiseo M, Circulating DNA. In diagnosis and monitoring EGFR gene mutations in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:584–97.

ESMO Guideline Committee: New eUpdate featuring Updated Treatment Algorithms for Metastatic Non-small-cell Lung Cancer. 2017. http://www.esmo.org/Guidelines/Lung-and-Chest-Tumours/Metastatic-Non-Small-Cell-Lung-Cancer/eUpdate-Treatment-Algorithms. Accessed 28 June 2017.

Jenkins S, Yang J, Ramalingam S, Yu K, Patel S, Weston S, Lawrance R, Cantarini M, Janne P, Mitsudomi T. 134O_PR: plasma ctDNA analysis for detection of EGFR T790M mutation in patients (pts) with EGFR mutation-positive advanced non-small cell lung cancer (aNSCLC). J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:S153–4.

Jenkins S, Yang JC, Ramalingam SS, Yu K, Patel S, Weston S, Hodge R, Cantarini M, Janne PA, Mitsudomi T, Goss GD. Plasma ctDNA analysis for detection of the EGFR T790M mutation in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:1061–70.

Kimura H, Suminoe M, Kasahara K, Sone T, Araya T, Tamori S, Koizumi F, Nishio K, Miyamoto K, Fujimura M, Nakao S. Evaluation of epidermal growth factor receptor mutation status in serum DNA as a predictor of response to gefitinib (IRESSA). Br J Cancer. 2007;97:778–84.

Sacher AG, Paweletz C, Dahlberg SE, Alden RS, O'Connell A, Feeney N, Mach SL, Janne PA, Oxnard GR. Prospective validation of rapid plasma genotyping for the detection of EGFR and KRAS mutations in advanced lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1014–22.

Nishie K, Kawaguchi T, Tamiya A, Mimori T, Takeuchi N, Matsuda Y, Omachi N, Asami K, Okishio K, Atagi S, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors beyond progressive disease: a retrospective analysis for Japanese patients with activating EGFR mutations. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:1722–7.

Park K, Yu CJ, Kim SW, Lin MC, Sriuranpong V, Tsai CM, Lee JS, Kang JH, Chan KC, Perez-Moreno P, et al. First-line Erlotinib therapy until and beyond response evaluation criteria in solid tumors progression in Asian patients with epidermal growth factor receptor mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: the ASPIRATION study. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:305–12.

Chmielecki J, Foo J, Oxnard GR, Hutchinson K, Ohashi K, Somwar R, Wang L, Amato KR, Arcila M, Sos ML, et al. Optimization of dosing for EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer with evolutionary cancer modeling. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:90ra59.

Chaft JE, Oxnard GR, Sima CS, Kris MG, Miller VA, Riely GJ. Disease flare after tyrosine kinase inhibitor discontinuation in patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancer and acquired resistance to erlotinib or gefitinib: implications for clinical trial design. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:6298–303.

Mok TSK, Kim S-W, Wu Y-L, Nakagawa K, Yang J-J, Ahn M-J, Wang J, Yang JC-H, Lu Y, Atagi S, et al: Gefitinib Plus Chemotherapy Versus Chemotherapy in Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutation–Positive Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer Resistant to First-Line Gefitinib (IMPRESS): Overall Survival and Biomarker Analyses. J Clin Oncol, 0:JCO.2017.2073.9250.

Wu JY, Shih JY, Yang CH, Chen KY, Ho CC, Yu CJ, Yang PC. Second-line treatments after first-line gefitinib therapy in advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:247–55.

Goldberg SB, Oxnard GR, Digumarthy S, Muzikansky A, Jackman DM, Lennes IT, Sequist LV. Chemotherapy with Erlotinib or chemotherapy alone in advanced non-small cell lung cancer with acquired resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Oncologist. 2013;18:1214–20.

Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, Biesma B, Vansteenkiste J, Manegold C, Serwatowski P, Gatzemeier U, Digumarti R, Zukin M, et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3543–51.

Paz-Ares LG, Marinis Fd DM, Thomas M, Pujol J-L, Bidoli P, Molinier O, Sahoo TP, Laack E, Reck M, et al. PARAMOUNT: final overall survival results of the phase III study of maintenance Pemetrexed versus placebo immediately after induction treatment with Pemetrexed plus cisplatin for advanced nonsquamous non–small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2895–902.

Sequist LV, Soria J-C, Goldman JW, Wakelee HA, Gadgeel SM, Varga A, Papadimitrakopoulou V, Solomon BJ, Oxnard GR, Dziadziuszko R, et al. Rociletinib in EGFR-mutated non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1700–9.

Mok TS, Wu YL, Ahn MJ, Garassino MC, Kim HR, Ramalingam SS, Shepherd FA, He Y, Akamatsu H, Theelen WS, et al. Osimertinib or platinum-Pemetrexed in EGFR T790M-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:629–40.

Govindan R. Overcoming Resistance to Targeted Therapy for Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1760–61.

Walter AO, Sjin RT, Haringsma HJ, Ohashi K, Sun J, Lee K, Dubrovskiy A, Labenski M, Zhu Z, Wang Z, et al. Discovery of a mutant-selective covalent inhibitor of EGFR that overcomes T790M-mediated resistance in NSCLC. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:1404–15.

Zhou W, Ercan D, Chen L, Yun CH, Li D, Capelletti M, Cortot AB, Chirieac L, Iacob RE, Padera R, et al. Novel mutant-selective EGFR kinase inhibitors against EGFR T790M. Nature. 2009;462:1070–4.

Lee K-O, Cha MY, Kim M, Song JY, Lee J-H, Kim YH, Lee Y-M, Suh KH, Son J. Abstract LB-100: Discovery of HM61713 as an orally available and mutant EGFR selective inhibitor. Cancer Research. 2014;74:LB-100-LB-100.

Cross DA, Ashton SE, Ghiorghiu S, Eberlein C, Nebhan CA, Spitzler PJ, Orme JP, Finlay MR, Ward RA, Mellor MJ, et al. AZD9291, an irreversible EGFR TKI, overcomes T790M-mediated resistance to EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:1046–61.

Planchard D, Brown KH, Kim DW, Kim SW, Ohe Y, Felip E, Leese P, Cantarini M, Vishwanathan K, Janne PA, et al. Osimertinib western and Asian clinical pharmacokinetics in patients and healthy volunteers: implications for formulation, dose, and dosing frequency in pivotal clinical studies. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;77:767–76.

Vishwanathan K, Dickinson PA, Bui K, Weilert DK, So K, Thomas K, Lisbon EA, Plummer R. Abstract B153: effect of food and gastric pH modifiers on the pharmacokinetics of AZD9291. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:B153-B153.

Jänne PA, Yang JC-H, Kim D-W, Planchard D, Ohe Y, Ramalingam SS, Ahn M-J, Kim S-W, Su W-C, Horn L, et al. AZD9291 in EGFR inhibitor–resistant non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1689–99.

Yang J, Ramalingam SS, Jänne PA, Cantarini M, Mitsudomi T. J Thoracic Oncol. 2016;11:S152–3.

Ballard P, Yates JW, Yang Z, Kim DW, Yang JC, Cantarini M, Pickup K, Jordan A, Hickey M, Grist M, et al. Preclinical comparison of Osimertinib with other EGFR-TKIs in EGFR-mutant NSCLC brain metastases models, and early evidence of clinical brain metastases activity. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:5130–40.

Koba T, Kijima T, Takimoto T, Hirata H, Naito Y, Hamaguchi M, Otsuka T, Kuroyama M, Nagatomo I, Takeda Y, et al. Rapid intracranial response to osimertinib, without radiotherapy, in nonsmall cell lung cancer patients harboring the EGFR T790M mutation: two case reports. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e6087.

Yang JC-H, Cho BC, Kim D-W, Kim S-W, Lee J-S, Su W-C, John T, Kao SC-H, Natale R, Goldman JW, et al. Osimertinib for patients (pts) with leptomeningeal metastases (LM) from EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): updated results from the BLOOM study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2020–2020.

Sjin RT, Lee K, Walter AO, Dubrovskiy A, Sheets M, Martin TS, Labenski MT, Zhu Z, Tester R, Karp R, et al. In Vitro and In Vivo Characterization of Irreversible Mutant-Selective EGFR Inhibitors That Are Wild-Type Sparing. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:1468–79.

Sequist LV, Soria JC, Camidge DR. Update to Rociletinib data with the RECIST confirmed response rate. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2296–7.

Sequist LV, Piotrowska Z, Niederst MJ, Heist RS, Digumarthy S, Shaw AT, Engelman JA. Osimertinib responses after disease progression in patients who had been receiving Rociletinib. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:541–3.

Park K, Lee J-S, Lee KH, Kim J-H, Min YJ, Cho JY, Han J-Y, Kim B-S, Kim J-S, Lee DH, et al. Updated safety and efficacy results from phase I/II study of HM61713 in patients (pts) with EGFR mutation positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who failed previous EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI). J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:8084–8084.

Park K, Lee J-S, Lee KH, Kim J-H, Cho BC, Min YJ, Cho JY, Han J-Y, Kim B-S, Kim J-S, et al. BI 1482694 (HM61713), an EGFR mutant-specific inhibitor, in T790M+ NSCLC: efficacy and safety at the RP2D. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:9055–9055.

Chen KL, Cho YT, Yang CW, Sheen YS, Liang CW, Lacouture ME, Chu CY. Olmutinib-induced palmoplantar keratoderma. British J Dermatol; 2017. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.15935. [Epub ahead of print]

Konagai S, Sakagami H, Yamamoto H, Tanaka H, Matsuya T, Mimasu S, Tomimoto Y, Mori M, Koshio H, Hirano M, et al. Abstract 2586: ASP8273 selectively inhibits mutant EGFR signal pathway and induces tumor shrinkage in EGFR mutated tumor models. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2586–2586.

Yu H, Spira AI, Horn L, Weiss J, West H, Giaccone G, Evans TL, Kelly RJ, Desai BB, Krivoshik A, et al. A phase 1, dose escalation study of oral ASP8273 in patients with non-small cell lung cancers with epidermal growth factor receptor mutations. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;

Tan DS-W, Yang JC-H, Leighl NB, Riely GJ, Sequist LV, Felip E, Seto T, Wolf J, Moody SE, Adams K, et al. Updated results of a phase 1 study of EGF816, a third-generation, mutant-selective EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring T790M. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:9044–9044.

Wu YL, Zhou Q, Liu X, Zhang L, Zhou J, Wu L, An T, Cheng Y, Zheng X, Hu B, et al. MA16.06 Phase I/II Study of AC0010, Mutant-Selective EGFR Inhibitor, in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Patients with EGFR T790M Mutation. J Thoracic Oncol. 12:S437–8.

Planken S, Behenna DC, Nair SK, Johnson T, Nagata A, Almaden C, Bailey S, Ballard TE, Bernier L, Cheng H, et al. Discovery of N-((3R,4R)-4-Fluoro-1-(6-((3-methoxy-1-methyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)amino)-9-methyl-9H- purin-2-yl)pyrrolidine-3-yl)acrylamide (PF-06747775) through structure-based drug design: a high affinity irreversible inhibitor targeting oncogenic EGFR mutants with selectivity over wild-type EGFR. J Med Chem. 2017;60:3002–19.

Belani CP, Nemunaitis JJ, Chachoua A, Eisenberg PD, Raez LE, Cuevas JD, Mather CB, Benner RJ, Meech SJ. Phase 2 trial of erlotinib with or without PF-3512676 (CPG 7909, a toll-like receptor 9 agonist) in patients with advanced recurrent EGFR-positive non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2013;14:557–63.

Janjigian YY, Smit EF, Groen HJ, Horn L, Gettinger S, Camidge DR, Riely GJ, Wang B, Fu Y, Chand VK, et al. Dual inhibition of EGFR with afatinib and cetuximab in kinase inhibitor-resistant EGFR-mutant lung cancer with and without T790M mutations. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:1036–45.

Liao BC, Lin CC, Lee JH, Yang JC. Optimal management of EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer with disease progression on first-line tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. Lung Cancer. 2017;110:7–13.

Bean J, Brennan C, Shih JY, Riely G, Viale A, Wang L, Chitale D, Motoi N, Szoke J, Broderick S, et al. MET amplification occurs with or without T790M mutations in EGFR mutant lung tumors with acquired resistance to gefitinib or erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20932–7.

Camidge DR, Moran T, Demedts I, Grosch H, Mercurio J-PD, Mileham KF, Molina JR, Vidal OJ, Bepler G, Goldman JW, et al. A randomized, open-label, phase 2 study of emibetuzumab plus erlotinib (LY+E) and emibetuzumab monotherapy (LY) in patients with acquired resistance to erlotinib and MET diagnostic positive (MET dx+) metastatic NSCLC. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:9070–9070.

Azuma K, Hirashima T, Yamamoto N, Okamoto I, Takahashi T, Nishio M, Hirata T, Kubota K, Kasahara K, Hida T, et al. Phase II study of erlotinib plus tivantinib (ARQ 197) in patients with locally advanced or metastatic EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer just after progression on EGFR-TKI, gefitinib or erlotinib. ESMO Open. 2016;1:e000063.

Wu Y-L, Kim D-W, Felip E, Zhang L, Liu X, Zhou CC, Lee DH, Han J-Y, Krohn A, Lebouteiller R, et al. Phase (Ph) II safety and efficacy results of a single-arm ph ib/II study of capmatinib (INC280) + gefitinib in patients (pts) with EGFR-mutated (mut), cMET-positive (cMET+) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:9020–9020.

Oxnard GR, Ramalingam SS, Ahn M-J, Kim S-W, Yu HA, Saka H, Horn L, Goto K, Ohe Y, Cantarini M, et al. Preliminary results of TATTON, a multi-arm phase Ib trial of AZD9291 combined with MEDI4736, AZD6094 or selumetinib in EGFR-mutant lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2509–2509.

Ahn MJ, Yang J, Yu H, Saka H, Ramalingam S, Goto K, Kim SW, Yang L, Walding A, Oxnard GR. 136O: Osimertinib combined with durvalumab in EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer: Results from the TATTON phase Ib trial. J Thoracic Oncol. 11:S115.

Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, Spigel DR, Steins M, Ready NE, Chow LQ, Vokes EE, Felip E, Holgado E, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1627–39.

Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, Felip E, Perez-Gracia JL, Han JY, Molina J, Kim JH, Arvis CD, Ahn MJ, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1540–50.

Gainor JF, Shaw AT, Sequist LV, Fu X, Azzoli CG, Piotrowska Z, Huynh TG, Zhao L, Fulton L, Schultz KR, et al. EGFR mutations and ALK rearrangements are associated with low response rates to PD-1 pathway blockade in non-small cell lung cancer: a retrospective analysis. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:4585–93.

Akbay EA, Koyama S, Carretero J, Altabef A, Tchaicha JH, Christensen CL, Mikse OR, Cherniack AD, Beauchamp EM, Pugh TJ, et al. Activation of the PD-1 pathway contributes to immune escape in EGFR-driven lung tumors. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:1355–63.

Haratani K, Hayashi H, Tanaka T, Kaneda H, Togashi Y, Sakai K, Hayashi K, Tomida S, Chiba Y, Yonesaka K, et al. Tumor immune microenvironment and nivolumab efficacy in EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer based on T790M status after disease progression during EGFR-TKI treatment. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1532–9.

Brevet M, Johnson ML, Azzoli CG, Ladanyi M. Detection of EGFR mutations in plasma DNA from lung cancer patients by mass spectrometry genotyping is predictive of tumor EGFR status and response to EGFR inhibitors. Lung Cancer. 2011;73:96–102.

Bai H, Mao L, Wang HS, Zhao J, Yang L, An TT, Wang X, Duan CJ, Wu NM, Guo ZQ, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in plasma DNA samples predict tumor response in Chinese patients with stages IIIB to IV non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2653–9.

Xu F, Wu J, Xue C, Zhao Y, Jiang W, Lin L, Wu X, Lu Y, Bai H, Xu J, et al. Comparison of different methods for detecting epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in peripheral blood and tumor tissue of non-small cell lung cancer as a predictor of response to gefitinib. Onco Targets Ther. 2012;5:439–47.

Douillard JY, Ostoros G, Cobo M, Ciuleanu T, Cole R, McWalter G, Walker J, Dearden S, Webster A, Milenkova T, McCormack R. Gefitinib treatment in EGFR mutated caucasian NSCLC: circulating-free tumor DNA as a surrogate for determination of EGFR status. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9:1345–53.

Hu C, Liu X, Chen Y, Sun X, Gong Y, Geng M, Bi L. Direct serum and tissue assay for EGFR mutation in non-small cell lung cancer by high-resolution melting analysis. Oncol Rep. 2012;28:1815–21.

Reckamp KL, Melnikova VO, Karlovich C, Sequist LV, Camidge DR, Wakelee H, Perol M, Oxnard GR, Kosco K, Croucher P, et al. A highly sensitive and quantitative test platform for detection of NSCLC EGFR mutations in urine and plasma. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:1690–700.

Murphy DM, Angiuoli SV, Chesnick B, Galens K, Jones S, Kadan M, Kann LM, Lytle K, Nesselbush M, Parpart-Li S, et al. A comprehensive noninvasive approach for the stratification of lung cancer patients for targeted therapies. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:e22086-e22086.

Forshew T, Murtaza M, Parkinson C, Gale D, Tsui DW, Kaper F, Dawson SJ, Piskorz AM, Jimenez-Linan M, Bentley D, et al. Noninvasive identification and monitoring of cancer mutations by targeted deep sequencing of plasma DNA. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:136ra168.

Karachaliou N, Mayo-de Las Casas C, Queralt C, De Aguirre I, Melloni B, Cardenal F, Garcia-Gomez R, Massuti B, Sanchez JM, Porta R, et al. Association of EGFR L858R mutation in circulating free DNA with survival in the EURTAC trial. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:149–57.

Nagai Y, Miyazawa H, Huqun TT, Udagawa K, Kato M, Fukuyama S, Yokote A, Kobayashi K, Kanazawa M, Hagiwara K. Genetic heterogeneity of the epidermal growth factor receptor in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines revealed by a rapid and sensitive detection system, the peptide nucleic acid-locked nucleic acid PCR clamp. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7276–82.

Yang J, Ramalingam SS, Janne PA, Cantarini M, Mitsudomi T. LBA2_PR: Osimertinib (AZD9291) in pre-treated pts with T790M-positive advanced NSCLC: updated phase 1 (P1) and pooled phase 2 (P2) results. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:S152–3.

Park K, Lee JS, Han JY, Lee KH, Kim JH, Cho EK, Cho JY, Min YJ, Kim JS, Kim DW. 1300: efficacy and safety of BI 1482694 (HM61713), an EGFR mutant-specific inhibitor, in T790M-positive NSCLC at the recommended phase II dose. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:S113.

Yu HA, Spira AI, Horn L, Weiss J, West HJ, Giaccone G, Evans TL, Kelly RJ, Desai BB, Krivoshik A, et al. Antitumor activity of ASP8273 300 mg in subjects with EGFR mutation-positive non-small cell lung cancer: interim results from an ongoing phase 1 study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:9050–9050.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SGW and JYS both completed data collection, literature search, generation of figures, and writing of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Jin-Yuan Shih has received speaking honoraria from AstraZeneca, Roche, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, and Eli Lilly. Shang-Gin Wu has no conflicts of interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, SG., Shih, JY. Management of acquired resistance to EGFR TKI–targeted therapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer 17, 38 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-018-0777-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-018-0777-1