Abstract

Background

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-activating mutations are major determinants in predicting the tumor response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Noninvasive test for the detection of EGFR mutations is required, especially in NSCLC patients from whom tissue is not available. In this study, we assessed the feasibility of detection of EGFR mutations in free DNA circulating in plasma.

Methods

Plasma samples of 60 patients with partial response to gefitinib were analyzed to detect EGFR-activating mutations in exons 19 and 21. Forty (66.7%) of patients had tumor EGFR mutation results. EGFR mutations in plasma were detected using the peptide nucleic acid (PNA)-mediated polymerase chain reaction (PCR) clamping method. All clinical data and plasma samples were obtained from 11 centers of the Korean Molecular Lung Cancer Group (KMLCG).

Results

Of the 60 patients, 39 were female and the median age was 62.5 years. Forty-three patients never smoked, 53 had adenocarcinomas, and seven had other histologic types. EGFR-activating mutation was detected in plasma of 10 cases (exon 19 deletion in seven and exon 21 L858R point mutation in three). It could not be found in plasma after treatment for 2 months. When only patients with confirmed EGFR mutation in tumor were analyzed, 17% (6 of 35) of them showed positive plasma EGFR mutation and the mutation type was completely matched with that in tumor. There was no statistically significant difference in clinical parameters between patients with EGFR mutations in plasma and those without EGFR mutations.

Conclusions

The detection rate of EGFR mutations from plasma was not so high despite highly sensitive EGFR mutation test suggesting that more advances in detection methods and further exploration of characteristics of circulating free DNA are required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations, such as deletions in exon 19 and point mutations in exon 21, are considered the most reliable predictive factors of outcome after treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs). Gefitinib was approved as a first-line therapy for NSCLC based on the results of a phase III landmark study, the Iressa Pan-Asia Study (IPASS), which showed that gefitinib conferred a survival benefit in EGFR mutation-positive patients over conventional chemotherapy [1]. The trial clearly showed that the selection of EGFR-TKIs should be based on molecular markers, not on clinical characteristics. Since then, given that many patients cannot receive second-line therapy after first-line failure because of their generally deteriorating condition, EGFR mutation testing is requested more frequently at the time of diagnosis for patients with adenocarcinoma. Indeed, a European workshop on EGFR mutation testing in NSCLC recommended testing at diagnosis, or at relapse, whenever possible, although no gold standard testing method was chosen [2].

Despite their importance in clinical practice, there is often too little tissue available to examine EGFR status as most are obtained by small needle biopsy or extracted from body fluids rather than via a more aggressive surgical approach. Many investigators have tried to solve this problem, leading to the development of more sensitive techniques to detect EGFR mutations, such as the scorpion-amplified refractory mutation system (SARMS) and the peptide nucleic acid (PNA)-mediated polymerase chain reaction (PCR) clamping method [3–18]. In addition, it is suggested that the plasma of cancer patients contains circulating free DNA (cfDNA) originating from necrotic tumor cells sloughed from the tumor mass or from circulating tumor cells [19–21]. Attempts to detect EGFR mutations in cfDNA using these sensitive techniques are currently in progress. If proven feasible and reliable, the cfDNA test may have broad clinical applications because it is non-invasive, convenient and can be performed repeatedly. In addition, the test could help diagnose lung cancer in cases when an adequate tissue sample is difficult to obtain. Over the past several years, many reports have shown promising results and have supported the feasibility of the test [22–33]. However, the optimal methodology for mutation detection from cfDNA and the possibility for the replacement of tumor tissue to blood sample still need to be confirmed.

In the present study, we examined the status of EGFR mutations in cfDNA isolated from plasma samples by a PNA-mediated PCR clamping method (PNA test) to determine the utility of plasma as a surrogate tissue for EGFR mutation analysis.

Methods

Patients

The prospective multicenter study was conducted to analyze EGFR mutations in plasma samples. Sixty patients with advanced NSCLC were recruited from 11 hospitals of the Korean Molecular Lung Cancer Group (KMLCG) between May 2010 and March 2011. All participants had histological or cytological confirmation of advanced NSCLC and showed a partial response to gefitinib as a second-line therapy without regard to the EGFR mutation status. Written informed consents for the use of their blood were obtained from all patients. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of 11 institutions (Korea Cancer Center Hospital, Korea University Guro Hospital, Daegu Catholic University Medical Center, Pusan National University Hospital, Inje University Busan Paik Hospital, Asan Medical Center, Wonkwang University Hospital, Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital, Chonbuk National University Hospital, Chungnam National University Hospital, Hallym University Medical Center, Konkuk University Medical Center).

Plasma sample collection and DNA extraction

Whole blood specimens from patients were collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tubes before and 2 months after the initiation of gefitinib administration and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 minutes. The supernatants were collected and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 minutes. The final supernatants were transferred to Eppendorf tubes and stored at −70°C until DNA extraction. DNA was extracted from 1–2 ml of supernatant with a DNeasy blood kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The final elution volume for DNA extraction was 60 μl and the amount of plasma DNA used for mutation testing was 30 ng.

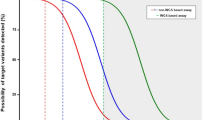

PNA-mediated real-time PCR clamping method to detect deletions in EGFR exon 19 and L858R point mutations in EGFR exon 21

Plasma DNA was analyzed using the PNAClampTM EGFR Mutation Detection kit (PANAGENE, Inc., Daejeon, Korea) as described in a previous retrospective study [34]. All reactions were conducted in a 20-μl volume using template DNA, primers and PNA probe set, and SYBR Green PCR master mix. All reagents were included in the kit. Real-time PCR reactions were performed using a CFX 96 instrument (Bio-Rad, USA). PCR cycling commenced with a 5 min hold at 94°C followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 70°C for 20 s, 63°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Two EGFR mutation types were detected using PNA-mediated real-time PCR. The efficiency of PCR clamping was determined by measuring the cycle threshold (Ct) value. Ct values for the control and mutation assays were obtained by observing the SYBR Green amplification plots. The delta Ct (∆Ct) value was calculated (control Ct − sample Ct), ensuring that the sample and control Ct values were from the test and wild-type control samples. The cut-off ∆Ct was defined as 2 for both the G746_A750 deletion and the L858R point mutation.

Tumor mutation data

At time of blood collection, we reviewed the EGFR mutation status in patient matched tumor tissue. By the direct sequencing used in routine practice at each institution to established EGFR mutation status in tumor tissue, forty tumor specimens were analyzed for EGFR mutations before gefitinib.

Statistical analyses

The relationship between EGFR mutations and demographic and clinical features, including age, gender, histological type, performance status (PS), smoking status, TNM stage and response to gefitinib, was analyzed using Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Two-sided P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

The clinical characteristics of the 60 patients are shown in Table 1. The median age was 62.5 years (range: 38–84 years). Thirty-nine (65.0%) of the patients were female and 21 (35.0%) were male. Forty-three patients (71.7%) were non-smokers. Fifty patients (83.3%) had good PS. The most common histological subtype was adenocarcinoma (53 patients, 88.3%) and the majority of patients (88.3%) had stage IV disease. As aforementioned, all the patients received second-line gefitinib treatment and showed partial response.

Detection of EGFR mutations in plasma

EGFR mutations were identified in 10/60 (16.7%) plasma samples by PNA testing. Of these, seven (70.0%) were in-frame deletions within exon 19 and three (30.0%) were arginine-to-leucine substitutions at amino acid 858 in exon 21 (L858R) (Table 2). After 2 months of treatment, a repetition of the test in EGFR mutation-positive patients showed that none had EGFR mutations.

Comparison of matched tumor sequencing and plasma EGFR mutations

To evaluate the accuracy of the results of the PNA test, we compared plasma EGFR mutations with tumor sequencing in 40 paired donor-matched plasma and tumor tissue specimens. EGFR mutations were detected in the plasma samples of six (15.0%) patients, including four deletions in exon 19 and two point mutations in exon 21. In the donor-matched tumor tissues, 35 mutations were detected (87.5%) by using direct sequencing, including 18 in exon 19 and 17 in exon 21. Of the patients with plasma EGFR mutations, mutations of identical exon site were detected in the matched tumor tissues (Table 3).

Correlation between EGFR mutation status assessed by PNA-mediated real-time PCR clamping and clinical features

EGFR mutations in plasma were detected more frequently in females (17.9% vs. 14.3% in male), non-smokers (18.6% vs. 11.8% in current/former smokers) and patients with stage IIIB disease (25.0% vs. 17.0% in stage IV). In addition, the overall mutation detection rate at the institute at which the central laboratory was located, and where sample processing did not require shipment, was relatively higher than that at the other institutes (23.8% vs. 12.8%); however, there were no statistically significant differences between the number of patients with EGFR mutations in plasma and those without (Table 4).

Discussion

Direct sequencing of amplified DNA products using Sanger’s method is the most popular test for detecting EGFR mutations. However, this method is limited by low sensitivity (meaning that the mutant DNA must represent greater than 25% of the total DNA), and requires multiple steps to be performed over several days [15]. Furthermore, in patients with advanced NSCLC, tumor tissue is not always available for EGFR mutation testing either because only small amounts of tissue are collected or because the tissues collected have very low, or non-existent, tumor content . For these reasons, new techniques are needed for more sensitive and rapid detection. Several new techniques, including SARMS, Taqman PCR, and denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (dHPLC) have been introduced, although none have been adopted as a standard method for detecting EGFR mutations [4, 5, 9–11, 13, 14, 16, 22–24, 26–28],[30–33].

Peptide nucleic acid (PNA) is an artificial polymer with the properties of both nucleic acids and proteins. PNA can bind tightly to complementary sequences in DNA because of a lack of electrostatic repulsion. Therefore, when a PNA oligomer, designed to detect an EGFR mutation and to bind to the antisense strand of the wild-type EGFR gene, is used for real-time PCR, amplification is rapid and sensitive and displays similar sensitivity to SARMS. Several studies using this novel method have been published [8, 17, 34, 35], however, to our knowledge, there are no reports showing detection of EGFR mutations in cfDNA extracted from the plasma of NSCLC patients using PNA-mediated real time PCR clamping.

In the present study, the detection rate of EGFR mutations in cfDNA was 16.1%. This is somewhat lower than that reported previously, which ranges from 20% to 73% (Table 5) [16, 24, 26–28, 32]. Mutation detection rates can differ between subjects and between methods. Around 50–60% of Asian patients and 20–30% of Western patients with adenocarcinomas are expected to carry activating EGFR mutations, while a negligible proportion of patients with other lung cancer histology are expected to carry such mutations. Therefore, the EGFR mutation detection rate can be estimated from the clinical and demographic parameters, including race and histology, of the study subjects. If we assume that 50% of Asian adenocarcinoma patients carry EGFR mutations, the expected detection rate in an Asian study population comprising 80% adenocarcinoma patients should be 40%. In this context, the results of several previous studies suggesting that the EGFR mutation test in cfDNA might be equivalent to that in tissue exceed the expected rate of EGFR positivity. Hence, it is difficult to accept these although the tests used in those studies are highly sensitive and always performed with the utmost precision. In addition, other reports published detection rates around 20% [26, 27], which is similar to our report, and still EGFR mutation testing in cfDNA has not been introduced in clinical practice in spite of such promising results over several years. Therefore, more data are required to evaluate the suitability of the cfDNA test and assess whether it can replace the traditional tumor tissue test.

The T790M mutation was not detected in any of the samples that were positive for activating EGFR mutations, although one report showed that low levels of T790M were detected in pretreatment tumor samples from 10/26 patients (38%) [24]. The detection rate of T790M seems to be closely associated with the sensitivity of the EGFR mutation test. A study using the BEAMing (beads, emulsion, amplification, and magnetics) method showed that the proportion of T790M within activating mutations ranged from 13.3–94.0%, and calculated that the T790M peak within the mutant allele fraction would range from 0.1–1% in cfDNA [32]. Therefore, even with a higher sensitivity permitting detection of 1% mutant DNA, as is reached with SARMS and PNA-based PCR clamping, detection of the T790M mutation in cfDNA remains difficult. This suggests that circulating tumor cells (CTC) would be a better alternative source material in which to detect the T790M mutation, and for predicting progression-free survival.

None of the EGFR mutations initially detected in cfDNA before treatment were detected 2 months after EGFR-TKI therapy and partial response. Since the initial tumor size and stage did not correlate with the detection rate, this result suggests that the amount of actively proliferating tumor cells, rather than the tumor burden, could affect the amount of circulating tumor DNA. Accordingly, in a previous CTC study, a 50% decline in CTCs within 1 week was noted in one patient, with the nadir reached 3 months after treatment, while the number of CTCs increased at the time of clinical progression and declined again when the tumor responded to subsequent chemotherapy [24]. It was also evident that, although CTC detection was not associated with initial tumor burden, there was a close concordance between tumor response and the number of CTCs during treatment.

Finally, our results suggest that better processing of plasma samples and on-site testing without necessity of sample delivery can improve detection rate.

In summary, our results show that, although detection of EGFR mutations in cfDNA is possible in some patients, more data are required to evaluate clinical applicability. Technical advances in sensitivity, stability and standardization are also needed, as well as adequate sample processing.

References

Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Yang CH, Chu DT, Saijo N, Sunpaweravong P, Han B, Margono B, Ichinose Y, Nishiwaki Y, Ohe Y, Yang JJ, Chewaskulyong B, Jiang H, Duffield EL, Watkins CL, Armour AA, Fukuoka M: Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009, 361: 947-957. 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699.

Pirker R, Herth FJ, Kerr KM, Filipits M, Taron M, Gandara D, Hirsch FR, Grunenwald D, Popper H, Smit E, Dietel M, Marchetti A, Manegold C, Schirmacher P, Thomas M, Rosell R, Cappuzzo F, Stahel R: European EGFR Workshop Group. Consensus for EGFR mutation testing in non-small cell lung cancer: results from a European workshop. J Thorac Oncol. 2010, 5: 1706-1713. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181f1c8de.

Marchetti A, Martella C, Felicioni L, Barassi F, Salvatore S, Chella A, Camplese PP, Iarussi T, Mucilli F, Mezzetti A, Cuccurullo F, Sacco R, Buttitta F: EGFR mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer: analysis of a large series of cases and development of a rapid and sensitive method for diagnostic screening with potential implications on pharmacologic treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2005, 23: 857-865. 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.043.

Endo K, Konishi A, Sasaki H, Takada M, Tanaka H, Okumura M, Kawahara M, Sugiura H, Kuwabara Y, Fukai I, Matsumura A, Yano M, Kobayashi Y, Mizuno K, Haneda H, Suzuki E, Iuchi K, Fujii Y: Epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutation in non-small cell lung cancer using highly sensitive and fast TaqMan PCR assay. Lung Cancer. 2005, 50: 375-384. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2005.08.009.

Zhou C, Ni J, Zhao Y, Su B: Rapid detection of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in non-small cell lung cancer using real-time polymerase chain reaction with TaqMan-MGB probes. Cancer J. 2006, 12: 33-39. 10.1097/00130404-200601000-00007.

Yatabe Y, Hida T, Horio Y, Kosaka T, Takahashi T, Mitsudomi T: A rapid, sensitive assay to detect EGFR mutation in small biopsy specimens from lung cancer. J Mol Diagn. 2006, 8: 335-341. 10.2353/jmoldx.2006.050104.

Pan Q, Pao W, Ladanyi M: Rapid polymerase chain reaction-based detection of epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in lung adenocarcinomas. J Mol Diagn. 2005, 7: 396-403. 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60569-7.

Tanaka T, Nagai Y, Miyazawa H, Koyama N, Matsuoka S, Sutani A, Huqun , Udagawa K, Murayama Y, Nagata M, Shimizu Y, Ikebuchi K, Kanazawa M, Kobayashi K, Hagiwara K: Reliability of the peptide nucleic acid-locked nucleic acid polymerase chain reaction clamp-based test for epidermal growth factor receptor mutations integrated into the clinical practice for non-small cell lung cancers. Cancer Sci. 2007, 98: 246-252. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00377.x.

Janne PA, Borras AM, Kuang Y, Rogers AM, Joshi VA, Liyanage H, Lindeman N, Lee JC, Halmos B, Maher EA, Distel RJ, Meyerson M, Johnson BE: A rapid and sensitive enzymatic method for epidermal growth factor receptor mutation screening. Clin Cancer Res. 2006, 12: 751-758. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2047.

Chin TM, Anuar D, Soo R, Salto-Tellez M, Li WQ, Ahmad B, Lee SC, Goh BC, Kawakami K, Segal A, Iacopetta B, Soong R: Detection of epidermal growth factor receptor variations by partially denaturing HPLC. Clin Chem. 2007, 53: 62-70.

Cohen V, Agulnik JS, Jarry J, Batist G, Small D, Kreisman H, Tejada NA, Miller WH, Chong G: Evaluation of denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography as a rapid detection method for identification of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in nonsmall-cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2006, 107: 2858-2865. 10.1002/cncr.22331.

Thomas RK, Nickerson E, Simons JF, Janne PA, Tengs T, Yuza Y, Garraway LA, LaFramboise T, Lee JC, Shah K, O’Neill K, Sasaki H, Lindeman N, Wong KK, Borras AM, Gutmann EJ, Dragnev KH, DeBiasi R, Chen TH, Glatt KA, Greulich H, Desany B, Lubeski CK, Brockman W, Alvarez P, Hutchison SK, Leamon JH, Ronan MT, Turenchalk GS, Egholm M, Sellers WR, Rothberg JM, Meyerson M: Sensitive mutation detection in heterogeneous cancer specimens by massively parallel picoliter reactor sequencing. Nat Med. 2006, 12: 852-855. 10.1038/nm1437.

Asano H, Toyooka S, Tokumo M, Ichimura K, Aoe K, Ito S, Tsukuda K, Ouchida M, Aoe M, Katayama H, Hiraki A, Sugi K, Kiura K, Date H, Shimizu N: Detection of EGFR gene mutation in lung cancer by mutant-enriched polymerase chain reaction assay. Clin Cancer Res. 2006, 12: 43-48. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0934.

Hoshi K, Takakura H, Mitani Y, Tatsumi K, Momiyama N, Ichikawa Y, Togo S, Miyagi T, Kawai Y, Kogo Y, Kikuchi T, Kato C, Arakawa T, Uno S, Cizdziel PE, Lezhava A, Ogawa N, Hayashizaki Y, Shimada H: Rapid detection of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer by the SMart-Amplification Process. Clin Cancer Res. 2007, 13: 4974-4983. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0509.

Pao W, Ladanyi M: Epidermal growth factor receptor mutation testing in lung cancer: searching for the ideal method. Clin Cancer Res. 2007, 13: 4954-4955. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1387.

Kimura H, Kasahara K, Kawaishi M, Kunitoh H, Tamura T, Holloway B, Nishio K: Detection of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in serum as a predictor of the response to gefitinib in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006, 12: 3915-3921. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2324.

Nagai Y, Miyazawa H, Huqun , Tanaka T, Udagawa K, Kato M, Fukuyama S, Yokote A, Kobayashi K, Kanazawa M, Hagiwara K: Genetic heterogeneity of the epidermal growth factor receptor in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines revealed by a rapid and sensitive detection system, the peptide nucleic acid-locked nucleic acid PCR clamp. Cancer Res. 2005, 65: 7276-7282. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0331.

John T, Liu G, Tsao MS: Overview of molecular testing in non-small-cell lung cancer: mutational analysis, gene copy number, protein expression and other biomarkers of EGFR for the prediction of response to tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Oncogene. 2009, 28 (Suppl 1): S14-S23.

Stroun M, Maurice P, Vasioukhin V, Lyautey J, Lederrey C, Lefort F, Rossier A, Chen XQ, Anker P: The origin and mechanism of circulating DNA. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000, 906: 161-168.

Stroun M, Lyautey J, Lederrey C, Olson-Sand A, Anker P: About the possible origin and mechanism of circulating DNA apoptosis and active DNA release. Clin Chim Acta. 2001, 313: 139-142. 10.1016/S0009-8981(01)00665-9.

Aung KL, Board RE, Ellison G, Donald E, Ward T, Clack G, Ranson M, Hughes A, Newman W, Dive C: Current status and future potential of somatic mutation testing from circulating free DNA in patients with solid tumours. Hugo J. 2010, 4: 11-21. 10.1007/s11568-011-9149-2.

Kimura H, Kasahara K, Shibata K, Sone T, Yoshimoto A, Kita T, Ichikawa Y, Waseda Y, Watanabe K, Shiarasaki H, Ishiura Y, Mizuguchi M, Nakatsumi Y, Kashii T, Kobayashi M, Kunitoh H, Tamura T, Nishio K, Fujimura M, Nakao S: EGFR mutation of tumor and serum in gefitinib-treated patients with chemotherapy-naive non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2006, 1: 260-267.

Kimura H, Suminoe M, Kasahara K, Sone T, Araya T, Tamori S, Koizumi F, Nishio K, Miyamoto K, Fujimura M, Nakao S: Evaluation of epidermal growth factor receptor mutation status in serum DNA as a predictor of response to gefitinib (IRESSA). Br J Cancer. 2007, 97: 778-784. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603949.

Maheswaran S, Sequist LV, Nagrath S, Ulkus L, Brannigan B, Collura CV, Inserra E, Diederichs S, Iafrate AJ, Bell DW, Digumarthy S, Muzikansky A, Irimia D, Settleman J, Tompkins RG, Lynch TJ, Toner M, Haber DA: Detection of mutations in EGFR in circulating lung-cancer cells. N Engl J Med. 2008, 359: 366-377. 10.1056/NEJMoa0800668.

Kuang Y, Rogers A, Yeap BY, Wang L, Makrigiorgos M, Vetrand K, Thiede S, Distel RJ, Jänne PA: Noninvasive detection of EGFR T790M in gefitinib or erlotinib resistant non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009, 15: 2630-2636. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2592.

Mack PC, Holland WS, Burich RA, Sangha R, Solis LJ, Li Y, Beckett LA, Lara PN, Davies AM, Gandara DR: EGFR mutations detected in plasma are associated with patient outcomes in erlotinib plus docetaxel-treated non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009, 4: 1466-1472. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181bbf239.

Jian G, Songwen Z, Ling Z, Qinfang D, Jie Z, Liang T, Caicun Z: Prediction of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in the plasma/pleural effusion to efficacy of gefitinib treatment in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2010, 136: 1341-1347. 10.1007/s00432-010-0785-z.

Bai H, Mao L, Wang HS, Zhao J, Yang L, An TT, Wang X, Duan CJ, Wu NM, Guo ZQ, Liu YX, Liu HN, Wang YY, Wang J: Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in plasma DNA samples predict tumor response in Chinese patients with stages IIIB to IV non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009, 27: 2653-2659. 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.3930.

He C, Liu M, Zhou C, Zhang J, Ouyang M, Zhong N, Xu J: Detection of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in plasma by mutant-enriched PCR assay for prediction of the response to gefitinib in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2009, 125: 2393-2399. 10.1002/ijc.24653.

Jiang B, Liu F, Yang L, Zhang W, Yuan H, Wang J, Huang G: Serum detection of epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations using mutant-enriched sequencing in Chinese patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Int Med Res. 2011, 39: 1392-1401. 10.1177/147323001103900425.

Brevet M, Johnson ML, Azzoli CG, Ladanyi M: Detection of EGFR mutations in plasma DNA from lung cancer patients by mass spectrometry genotyping is predictive of tumor EGFR status and response to EGFR inhibitors. Lung Cancer. 2011, 73: 96-102. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.10.014.

Taniguchi K, Uchida J, Nishino K, Kumagai T, Okuyama T, Okami J, Higashiyama M, Kodama K, Imamura F, Kato K: Quantitative detection of EGFR mutations in circulating tumor DNA derived from lung adenocarcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2011, 17: 7808-7815. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1712.

Nakamura T, Sueoka-Aragane N, Iwanaga K, Sato A, Komiya K, Abe T, Ureshino N, Hayashi S, Hosomi T, Hirai M, Sueoka E, Kimura S: A noninvasive system for monitoring resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors with plasma DNA. J Thorac Oncol. 2011, 6: 1639-1648. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31822956e8.

Kim HJ, Lee KY, Kim YC, Kim KS, Lee SY, Jang TW, Lee MK, Shin KC, Lee GH, Lee JC, Lee JE, Kim SY: Detection and comparison of peptide nucleic acid-mediated real-time polymerase chain reaction clamping and direct gene sequencing for epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2011, 75: 321-325.

Han HS, Lim SN, An JY, Lee KM, Choe KH, Lee KH, Kim ST, Son SM, Choi SY, Lee HC, Lee OJ: Detection of EGFR mutation status in lung adenocarcinoma specimens with different proportions of tumor cells using two methods of differential sensitivity. J Thorac Oncol. 2012, 7: 355-364. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31823c4c1b.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the Korean association for the study of lung cancer (KASLC-1001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors had no competing interest to declare.

Authors’ contributions

YCK, SHJ, KYL and JCL contributed to study conception and design. SYL, DSH, MKL, HKL, CMC, SHY, YCK and SYK were involved in acquisition and analysis of data, HRK and JCL wrote the manuscript. KYL confirmed the final draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Jae Cheol Lee and Kye Young Lee contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, HR., Lee, S.Y., Hyun, DS. et al. Detection of EGFR mutations in circulating free DNA by PNA-mediated PCR clamping. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 32, 50 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-9966-32-50

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-9966-32-50