Abstract

Epidemiological evidence has linked air pollution with adverse respiratory outcomes, but the mechanisms underlying susceptibility to air pollution remain unclear. This study aimed to investigate the role of glutathione S-transferase (GST) polymorphism in the association between air pollution and lung function levels. A total of 75 healthy young volunteers aged 18–20 years old were recruited for six follow-up visits and examinations. Spirometry was conducted to obtain lung function parameters such as forced vital capacity (FVC), and forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1). Nasal fluid concentrations of interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-8 (IL-8), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and 8-epi-prostaglandin F2α (8-epi-PGF2a) were measured using ELISA kits. Linear mixed-effect models were used to evaluate the association of air pollutants with respiratory outcomes. Additionally, polymorphisms of glutathione S-transferase mu 1 (GSTM1) and glutathione S-transferase theta 1 (GSTT1) were estimated to explore its role in the association between air pollutants and lung function. We found that short-term exposure to atmospheric particulates such as PM2.5 and PM10 can cause an increase in nasal biomarkers of inflammation, oxidative stress, and lung function, while air gaseous pollutant exposure is linked with decreased lung function, except for CO. Stratification analyses showed that an increase in nasal inflammatory cytokines caused by exposure to atmospheric particulates is more obvious in subjects with GSTM1-sufficient (GSTM1+) than GSTM1-null (GSTM1−), while elevated lung function levels due to air particles are more significant in subjects with the genotype of GSTM1− when compared to GSTM1+. As for air gaseous pollutants, decreased lung function levels caused by O3, SO2, and NO2 exposure is more manifest in subjects with the genotype of GSTM1− compared to GSTM1+. Taken together, short-term exposure to air pollutants is associated with alterations in nasal biomarkers and lung function levels in young healthy adults, and susceptible genotypes play an important mediation role in the association between exposure to air pollutants and inflammation, oxidative stress, and lung function levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

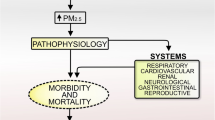

Air pollution is a global problem that has overtaken other environmental risks to become the fourth overall risk factor for death and the first major environmental risk factor due to the economy's rapid growth and the steady promotion of urbanization. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019, air pollution is responsible for seven million deaths worldwide, or 11.75% of all fatalities [1]. Air pollution is complicated and characterized by high concentrations of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and ozone (O3) in China because of rising coal consumption, automobile ownership, and industrial emissions [2]. Due to its small size, PM2.5 can enter the lung through the ciliated airway, and some of it can also the blood–brain barrier and enter the blood circulation [3]. Haze, characterized by a higher level of PM2.5, has a wide range of impacts, including making life, travel and work more difficult or inconvenience, as well as having a negative impact on public health [4–6]. Respiratory health is most affected by air pollution because the respiratory system is the first line of the body to contact and resist air pollutants.

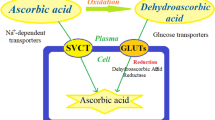

Air pollution can decrease lung function and increase the risk of pathogenesis or exacerbation of respiratory diseases such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pneumonia, and lung cancer [7–17]. However, genetic susceptibility to air pollutants like PM2.5, coarser particulate matter (PM10), O3, sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and carbon monoxide (CO) varies from person to person [18–20]. Inflammation and oxidative stress are, according to previous research, the primary underlying cause of respiratory damage caused by air pollution. [21–23]. Glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) have been implicated in the maintenance of cell integrity, defense against oxidative stress and DNA damage, and detoxification of endogenous and exogenous compounds in the cell [24]. The absence of bioactive antioxidant protein expression in the GSTT1 null (GSTT1−) and GSTM1 null (GSTM1−) genotypes reduces the body's antioxidant capacity [25]. The prevalence of GSTM1-null and GSTT1-null polymorphisms across ethnic groups varied from 18 to 66% and 10% to 58%, respectively [26–28].

There were fewer epidemiological studies investigating the respiratory effects of air pollution exposure between different genotypes of GSTM1 and GSTT1, and the existing research results were inconsistent [29]. For example, Gilliland et al. displayed that children with GSTM1− and GSTP1− genotypes have higher lung function levels such as FVC and FEV1 when compared to their peers with GSTM1+ and GSTP1+ [30]. He et al. indicated that smokers with GST null genotypes have a more obvious decline in lung function than GST sufficient genotypes [31]. Imboden et al. found that there was an accelerating decline in lung function in the general male population with genetic GSTT1 deficiency, but not females [22, 32], reported that the frequency of incense burning at home increased the risk of current asthma and exercise wheeze among children with GSTT1− genotype [33]. However, several studies demonstrated that there were no significant associations between GST variation and respiratory outcomes [34–36]. Therefore, more optimized research is needed to further confirm the mediation role of susceptible genotypes in air pollution and human health.

In this panel study, 75 undergraduates from Xinxiang Medical University between the ages of 18 and 21 were recruited to investigate the influence of exposure to air pollutants on acute respiratory inflammation and the underlying mechanisms based on inflammatory biomarkers like interleukin-6 (IL-6); interleukin-8 (IL-8); fibroblast growth factor (FGF-); as well as 8-epi-prostaglandin F2 (8-epi-PGF2); Additionally, the genotype strata were administered in order to evaluate the potential modifying effect of GSTM1- and GSTT1-null genotypes on associations between exposure to air pollution and adverse respiratory effects.

Materials and methods

Study design and participant recruitment

We scheduled a longitudinal panel study among freshmen from Xinxiang Medical University in Central China from September 23 to December 23 with six follow-ups lasting at least one week (Fig. 1). Before the follow-up study, a baseline survey was done, and questionnaires were used to get information about each individual's gender, age, weight, height, smoking and alcohol use, health, cardiovascular, and respiratory histories through face to face interview. Exposure levels of air pollutants were consecutively monitored for 7 days before the physical examination. Thee inclusion criteria of the participant’s health status were no smoking, no drinking, no cardiovascular and respiratory symptoms or diseases, and other chronic disorders. To reduce heterogeneity in lifestyle, dietary habits, and concurrent exposure to other pollutants, we excluded seven participants who lived off campus. Finally, this study included 75 participants who met the study's eligibility requirements. All participants agreed and completed their written informed consent after receiving detailed explanations of the study and potential consequences before enrollment. This study protocol was approved by the Human Ethical Committee of Xinxiang Medical University, China (NO. 2017–02-0623).

Exposure measurements

The air pollution exposure data were obtained from a real-time data acquisition and automatic quality control system of air monitoring stations (Thermo Fisher Scientific Co., Ltd., Waltham, MA, USA), which was installed on the rooftop of a building with seven floors (about 21 m high) on the campus of Xinxiang Medical University. This site is close to the dorms, playgrounds, and classrooms of the participants at a distance smaller than 1000 m. Hourly PM2.5, PM10, O3, SO2, NO2, and CO concentrations (24-h average concentration) were measured before the day of health measurements, and meteorological data including temperature (T) and relative humidity (RH) were collected at the same time. Personal PM2.5 and PM10 sample exposure concentrations were calculated based on each physical examination time. The air quality complex index (AQCI) was calculated by the equation of AQCI = ∑ Ci/Si, where Ci is the concentration of air pollutants including PM2.5, PM10, O3, SO2, NO2, and CO; Si is the annual mean level II of the national ambient air quality standard of China (NAAQS-China). The average daily dose (ADD) of air pollutants for individuals was further evaluated based on the equation of ADD = AQCI × [inhalation rate/weight] [37].

Health measurements and lab analyses

Physical examination was conducted using an automatic digital height and weight measuring instrument (Omron HBF-371, Kyoto, Japan), and more detailed measurement information as described in our previous study [38]. Spirometry was performed using an electronic spirometer following the standardized procedures of the American Thoracic Society (ATS)-criteria (Chestgraph HI-801, CHEST Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Flow-volume curve manoeuvers and volume-time curves of lung function parameters such as forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), the ratio of FEV1 to FVC (FEV1/FVC), peak expiratory flow (PEF), forced expiratory flow at 25% of FVC (FEF25), forced expiratory flow at 75% of FVC (FEF75), maximal voluntary ventilation (MVV), and minute ventilation (MV) were measured three times, and the highest value of lung function parameters (the best test performance) was used in the analysis [39].

Commercially available assay kits were used to measure inflammatory biomarkers like IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-, as well as oxidative stress indicators like 8-epi-PGF2 in nasal epithelial lining fluid (ELF). Each participant had two nostrils sprayed with approximately 100 L of sterile normal saline, and their noses were kneaded until they were completely moist. To obtain nasal EFLs, the test paper was then inserted into the two nostrils with a length that was appropriate for the nasal cavity [40]. After being clamped for two minutes, the test strips were taken out, placed on a clean worktable with ventilation, and dried for 24 h at room temperature. Then, the test strips were eluted using the elution buffer composed of 1% BSA, 0.05% Triton X-100, and Dulbecco's PBS with 100 μLper strip. The supernatant was stored at -20℃ after centrifugation for 2 min at 13,000 rpm [19]. IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and 8-epi-PGF2α were measured with the corresponding ELISA Kits according to the guidelines of the manufacturers.

A total of 2 mL venous blood was collected from each participant into a vacuum blood collection tube. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood lymphocytes using a QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Polymorphisms of GSTM1 and GSTT1 were conducted using multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification. The primers of GSTM1 and GSTT1 were 5’-GAACTCCCTGAAAAGCTAAAGC-3’ (Forward) and 5’-GTTGGGCTCAAATATACGGTGG-3’ (Reverse), and 5’- TTCCTTACTGGTCCTCACATCTC-3’ (Forward) and 5’-TCACCG GATCATGGCCAGCA-3’ (Reverse), respectively (Table S1).

Statistical analyses

Linear mixed-effects models with a random intercept for each participant were used to evaluate the associations between air pollutants and health outcome biomarkers, which allow each subject to serve as his or her own control over time and has the advantage of explaining correlations among multiple repeated measurements collected per participant including a random intercept for each subject [19]. Health outcome data were log-transformed to improve normality and matched with air pollution data before the nasal epithelial lining fluid collection. Two different sets of exposure metrics (lag 0 to lag 6 and 1-d to 7-d moving averages) were used to identify the most relevant exposure metric(s), which may best capture the associations between air pollution and health indicators [41]. The single-constituent model was used to estimate the consistency of the examined association of specific air pollutants and biomarkers. The linear mixed-effects model was utilized to assess the mixed effect of air pollutants including PM2.5, PM10, O3, SO2, NO2, and CO on biomarkers such as IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and 8-epi-PGF2α in the current study. Air pollutant concentrations and health outcome data were merged by physical examination date. A series of potential confounders including age, body mass index, time trend, day-of-week, study location, temperature, and relative humidity were adjusted in the statistical models [42]. Results were demonstrated as estimated percent changes with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in biomarkers associated with interquartile range (IQR) increases in air pollutants. All analyses were conducted using software SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), and the significant level was set at p < 0.05 (2-tailed).

Results

Descriptive statistics of exposure and health measurements

A total of 75 volunteers participated in the physical examination. Air pollutants, blood samples, and nasal ELF were repeatedly collected and analyzed six times. The demographic characteristics of the 75 participants are shown in Table 1. There were 21 males and 54 females with an average age of 18.61 ± 0.72 years and a mean BMI of 20.84 ± 2.89 kg/m2. Among 75 volunteers, 35 and 38 subjects had GSTM1-sufficient (GSTM1+) and GSTT1-sufficient (GSTT1+) genes, respectively. The percentage of GSTM1-null (GSTM1−) and GSTT1-null (GSTT1−) was 53.3% and 49.3%, respectively. There was no significant difference between GST subgroup genotypes in age, sex, and BMI (Table 1).

The health characteristics of the participants are demonstrated in Table 2. The range of the concentrations of air pollutants was manifested as follows: PM2.5 (33.0 to 401.0 µg/m3), PM10 (22.0 to 369.0 µg/m3), O3 (00.0 to 200.0 µg/m3), SO2 (16.0 to 113.0 µg/m3), NO2 (14.0 to 119.0 µg/m3), and CO (0.8 to 6.0 mg/m3) during the period of the six visit time points (Table 2). The alterations in the concentration of air pollutants over time were inconsistent. ADD of air pollutants for undergraduates is 2.915 ± 0.399, and there is no significant difference in ADD and related subgroups between males and females (Table S2).

The average levels of lung function parameters including FVC, FEV1, FEV1/FVC, PEF, FEF25, FEF75, MVV, and MV were 3.09 L, 2.78 L, 90.83, 4.51 L/s, 2.43 L/s, 4.83 L/s, 84.65 L/min, and 8.82 L/min, respectively. Mean biomarker levels of IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and 8-epi-PGF2α in nasal ELF were 22.10 ng/mL, 28,944.30 ng/L, 44.51 pg/L, and 64,714.32, respectively. During the period of the study, the average concentrations of air pollutants including PM2.5, PM10, O3, SO2, NO2, and CO were 132.5 μg/m3, 148.0 μg/m3, 17.5 μg/m3, 31.0 μg/m3, 57.0 μg/m3, and 2.60 mg/m3, respectively. The average temperature and relative humidity were 6.8℃ and 50.0% during the period of this study, respectively.

Relationship between air pollutants and inflammatory mediators and lung function

Spearman correlation analyses were used to investigate the correlation between air pollutants, inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers, and lung function parameters.

Air pollutants such as PM2.5, PM10, NO2, SO2, and CO were positively correlated with each other except for O3 (Table 3). Additionally, ADD and related ADDPM2.5, ADDPM10, ADDSO2, ADDNO2, ADDO3, and ADDCO was significantly negatively correlated with FVC and FEV1. Moreover, the direction of correlation between each air pollutant and nasal biomarkers was not completely inconsistent in this study. However, there was no significant correlation between ADD and nasal biomarkers such as IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and 8-epi-PGF2a. Interestingly, nasal inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers, such as IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and 8-epi-PGF2a, were significantly positively correlated with FVC and FEV1 (Table 3).

Association and modification of GST polymorphisms effects of air pollutants on nasal biomarkers and lung function in undergraduates

Short-term exposure to atmospheric particulates such as PM2.5 and PM10 can cause an increase in nasal biomarkers of inflammatory and oxidative stress and lung function levels, whereas air gaseous pollutant exposure linked with alteration of nasal biomarkers of inflammatory and oxidative stress and decreased lung function levels, except for CO. Specifically, atmospheric particulate exposure can significantly increase the levels of IL-6 and TNF-α with the characteristics of accumulation with exposure days. For example, each IQR (112 μg/m3) increase in PM2.5 was associated with an increase in TNF-α by 81.57%, and each IQR (127 μg/m3) increase in PM10 was linked with an increase in IL-6 by 190.77%. In addition, each 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 were associated with increased FVC by 0.75% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.12%, 1.37%) at lag 7; each 10 μg/m3 increase in PM10 was associated with increased FVC by 2.36% (1.35%, 3.37%) at lag 5. Moreover, a 10 μg/m3 increase in PM10 was associated with a 1.41% (95%CI: 0.37%, 2.44%) increment in PEF and a 1.39% (0.32%, 2.46%) increment in MVV, respectively. However, each 10 μg/m3 increase in O3 was associated with reduced FVC by 15.61% (-25.10%, -6.13%) at lag 3. Short-term exposure to CO caused bidirectional changes in lung function parameters such as FVC, PEF, and MVV. In particular, CO exposure can lead to an increase in lung function at lag 1–4 days and subsequently result in a decline in lung function at lag 5–7 days (Fig. 3, Fig. S3, Fig. S4). In brief, there were different effects of particulate pollutants and gaseous pollutants in the atmosphere on the level of nasal biomarkers and lung function of undergraduates.

Stratification analyses allow us to have a clearer understanding of the health response of susceptibility genes with different genotypes when exposed to air pollutants. There is a positive trend between PM2.5 and percent change of IL-6 in the full GSTM1 population, and the trend is more pronounced in subjects with GSTM1+ genotype as PM2.5 exposure accumulates (Fig. 2A). Similarly, the concentration of TNF-α increases with the accumulation of PM2.5 exposure, and the trend is more manifest in subjects with (Fig. 2B). In addition, both nasal IL-8 and 8- epi-PGF2a demonstrated a consistently increasing trend as exposure to airborne particulates increases, although it is not statistically significant (Fig. S1). Notably, atmospheric gaseous pollutants did not show a good consistent trend with nasal biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress no matter what the GSTM1 genotype (data not shown). Alteration in lung function change is different when exposure to particulate pollutants and gaseous pollutants, and in the specific GSTM1 genotype. Specifically, exposure to PM2.5 and PM10 is associated with elevated lung function parameters such as FVC, PEF, and MVV in the full GSTM1 population, and the trend is more obvious in subjects with GSTM1− genotype as particulate exposure accumulates (Fig. 3, Fig. S2-S4). Exposure to O3, NO2, and SO2 leads to a reduction in lung function levels in the full GSTM1 population, although it is not statistically significant. It is worth mentioning that the above-mentioned trend is more visible in the subjects with GSTM1− genotype.

Discussion

Through a panel study of healthy undergraduates, this study investigated the association between exposure to major air pollutants, biomarkers of airway inflammation, and lung function. The influence of GST polymorphism modification on the effects of air pollutants on lung function was further investigated. Our results indicated that short-term particulate exposure including PM2.5 and PM10 was associated with an increase in IL-6, TNF-α, and lung function. However, exposure to gaseous pollutants including O3, SO2, and NO2 was associated with a decrease in lung function including FVC, FEV1, PEF, and MVV. In general, lung function levels are lower in subjects with the GSTM1− genotype than in those with the GSTM1+ genotype. A plethora of studies has investigated the influence of air pollutant exposure on lung function. However, the relationship between air pollution and lung function has been inconsistent. There was an inverse association between PM2.5 exposure and lung function according to most of the previous studies. For example, a recent study showed that short-term personal exposure to PM2.5 was linked with reduced spirometer parameters such as FVC and FEV1 of old adults from the South of China [43]. Similarly, short-term personal exposure to NO2 was associated with an increase of respiratory inflammation parameter as fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) and a decline in lung function levels such as FVC, FEV1 and PEF [44]. An areview indicated that an increase in outdoor air particulate pollutant exposure was associated with a decrease in FEV1 in healthy adults [45]. In addition, another study pointed out that short-term personal exposure to PM2.5 or ultrafine particles were not associated with lung function of old adults in the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Italy [46]. The results may be attributed to the low PM2.5 exposure levels of approximately to 15 μg/m3 in the above-mentioned studies. Additionally, a repeatedly-measured study with 34 healthy nonsmoking adult volunteers showed that short-term exposures to particulate matter were associated with slightly increased levels of FEV1 and FEF25-75 [47]. Another panel study demonstrated that a short-term averaging time (3-d moving average) air pollutant exposure was positively associated with lung function, while a longer averaging time (14-d moving average) air pollutant exposure was negatively associated with lung function [48].

In line with previous studies, there was an inverse relationship between lung function and atmospheric gaseous pollutants like O3, SO2, NO2, and CO [49]. However, we found a positive association between young healthy undergraduates' lung function and short-term exposure to PM2.5 or PM10, which was consistent with some previous studies [47,48]. The estimated effects of particulate matter on lung function are not only dependent on its exposure concentration and compositions but also influenced by characteristics of the exposure population such as age, genetics, and basic health status. In this study, particulate such as PM2.5 and PM10 mainly deposits on the upper respiratory tract and may not cause serious damage to the lower respiratory tract. In addition, the subjects are healthy young adults, and their bodies will produce compensatory and adaptive responses to particulate matter, which may explain the positive relationship between exposure to particulate matter and lung function in this study. Gaseous pollutants such as O3, SO2, NO2, and CO can be directly dissolved in the lower respiratory tract such as alveoli and bronchioles, leading to severe lung impairment, such as lower lung function even in healthy young adults.

Previous epidemiological studies have indicated that the underlying mechanisms of inflammation and oxidative stress play a critical role in driving the adverse respiratory effects of particulate matter. For example, PM2.5 exposure has been associated with elevated levels of inflammatory biomarkers including IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and FeNO, and oxidative stress biomarkers such as 8-epi-PGF2α [50–52], which is consistent with our results of atmospheric particulate exposure in the current study. A recent meta-analysis of 22 epidemiological studies reported that exposure to PM2.5 is associated with an increased level of IL-6 [53]. Another meta-analysis of 23 epidemiological studies summarized that PM2.5 exposure may contribute to increased levels of oxidative stress biomarkers such as malondialdehyde (MDA), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) [54]. In the current study, we found that exposure to PM2.5 and PM10 was associated with increased levels of nasal inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers such as IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and 8-epi-PGF2α.

There are numerous studies investigating the relationship between atmospheric gaseous pollutants such as O3, SO2, NO2, and CO and biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress including IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), and 8-epi-PGF2α. For instance, a panel study of young healthy students demonstrated that O3 and SO2 are the two major traffic-related pollutants positively associated with biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress such as high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), fibrinogen and 8-OHdG [55]. Average 2-week O3 exposure was significantly and positively associated with IL-1β, IL-8, IL-17A, IFN-γ, and TNF-α in healthy adults [56]. An increase in NO2 exposure was associated with elevated levels of IL-6 as well as IL-10 in 8-year-old children [57]. In addition, there was a negative correlation between SO2, NO2, or CO and fibrinogen in the male population [58]. Short-term exposure to NO2 and O3 and long-term exposure to CO were inversely associated with fibrinogen in Korean elderly adults [59]. However, there were a lot of studies with no significant results between other atmospheric gaseous pollutants not mentioned above and biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress [21, 56, 57]. In the present study, we found that there was no significant association between gaseous pollutants and inflammatory biomarkers such as IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and oxidative stress biomarker 8-epi-PGF2α in nasal epithelial lining fluid, which may be due to the short retention time and the lower absorption concentration of gaseous pollutants in the nasal cavity.

Previous studies have provided substantial evidence showing gene-air pollution interactions for cardiovascular outcomes [60]. However, the interplay of air pollution and specific genes related to detoxification (GSTM1 and GSTT1) on respiratory health is still lacking and unclear. This study demonstrated that the genetic susceptibility of GSTM1 and GSTT1 played a crucial role in influencing air pollution exposure on lung function. GSTM1-null (GSTM1−) and GSTT1-null (GSTT1−) individuals are more susceptible to air pollution exposure such as PM2.5 and PM10, distinguishing levels of biomarkers and lung function due to the lack of corresponding detoxifying enzymes when compared with their GSTM1-sufficient (GSTM1+) and GSTT1- sufficient (GSTT1+) peers, respectively. Deletion polymorphisms of the GST gene have an additive effect of air pollution on nasal mucus biomarkers and lung function. Previous studies confirmed that GST polymorphisms can modify the effect of air pollution on biomarkers and health outcomes [61–63]. Notably, the actual phenotype of health outcomes is determined by various factors such as heredity, environment, basic constitution, underlying health conditions, and their interactions.

This study has a few limitations. First, personal exposure levels of air pollutants derived from the fixed monitoring station may not reflect the actual exposure of each subject and lead to an underestimation of the influence of air pollutants. Second, due to the closer correlations among air pollutants, we did not run two pollutant models to distinguish the independent influence of each pollutant. Third, a large sample is a necessary condition for accurate estimation, and effect estimation accuracy may not be achieved with the small sample size. Fourth, other potential confounders may act because there are a lot of unmeasured air pollutants that might link with biomarkers and lung function. Finally, we did not estimate the interactive impact of other antioxidant enzyme genes with GST gene polymorphisms and air pollutants.

Conclusions

In summary, this study suggests that short-term exposure to air pollutants alters nasal biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress and lung function levels in young healthy adults. Nasal mucus sampling is a novel method worth popularizing for evaluating the effects of atmospheric pollutant exposure on respiratory health outcomes. GSTM1 genotypes play an important mediation role in the association between exposure to air pollutants and inflammation, oxidative stress, and lung function levels. This study may shed light on the mechanism of GST-related genotype and subsequent influence on human health.

References

GBD, C. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1223–49.

Xu P, Chen Y, Ye X. Haze, air pollution, and health in China. Lancet. 2013;382(9910):2067.

Xie W, You J, Zhi C, Li L. The toxicity of ambient fine particulate matter (PM2.5) to vascular endothelial cells. J Appl Toxicol. 2021;41(5):713–23.

Cai DP, He YM. Daily lifestyles in the fog and haze weather. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8(1):E75–7.

Hao Y, Zhao M, Lu ZN. What is the health cost of haze pollution? Evidence from China. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2019;34(4):1290–303.

Li M, Zhang L. Haze in China: current and future challenges. Environ Pollut. 2014;189:85–6.

Cai Y, Hansell AL, Granell R, Blangiardo M, Zottoli M, Fecht D, Gulliver J, Henderson AJ, Elliott P. Prenatal, early-life, and childhood exposure to air pollution and lung function: the ALSPAC cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(1):112–23.

Guarnieri M, Balmes JR. Outdoor air pollution and asthma. Lancet. 2014;383(9928):1581–92.

Hendryx M, Luo J, Chojenta C, Byles JE. Air pollution exposures from multiple point sources and risk of incident chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma. Environ Res. 2019;179(Pt A):108783.

Nhung N, Amini H, Schindler C, Kutlar JM, Dien TM, Probst-Hensch N, Perez L, Kunzli N. Short-term association between ambient air pollution and pneumonia in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of time-series and case-crossover studies. Environ Pollut. 2017;230:1000–8.

Raaschou-Nielsen O, Andersen ZJ, Beelen R, Samoli E, Stafoggia M, Weinmayr G, Hoffmann B, Fischer P, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Brunekreef B, Xun WW, Katsouyanni K, Dimakopoulou K, Sommar J, Forsberg B, Modig L, Oudin A, Oftedal B, Schwarze PE, Nafstad P, De Faire U, Pedersen NL, Ostenson CG, Fratiglioni L, Penell J, Korek M, Pershagen G, Eriksen KT, Sorensen M, Tjonneland A, Ellermann T, Eeftens M, Peeters PH, Meliefste K, Wang M, Bueno-de-Mesquita B, Key TJ, de Hoogh K, Concin H, Nagel G, Vilier A, Grioni S, Krogh V, Tsai MY, Ricceri F, Sacerdote C, Galassi C, Migliore E, Ranzi A, Cesaroni G, Badaloni C, Forastiere F, Tamayo I, Amiano P, Dorronsoro M, Trichopoulou A, Bamia C, Vineis P, Hoek G. Air pollution and lung cancer incidence in 17 European cohorts: prospective analyses from the European Study of Cohorts for Air Pollution Effects (ESCAPE). Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(9):813–22.

Usemann J, Decrue F, Korten I, Proietti E, Gorlanova O, Vienneau D, Fuchs O, Latzin P, Roosli M, Frey U. Exposure to moderate air pollution and associations with lung function at school-age: A birth cohort study. Environ Int. 2019;126:682–9.

Wang C, Xu J, Yang L, Xu Y, Zhang X, Bai C, Kang J, Ran P, Shen H, Wen F, Huang K, Yao W, Sun T, Shan G, Yang T, Lin Y, Wu S, Zhu J, Wang R, Shi Z, Zhao J, Ye X, Song Y, Wang Q, Zhou Y, Ding L, Yang T, Chen Y, Guo Y, Xiao F, Lu Y, Peng X, Zhang B, Xiao D, Chen CS, Wang Z, Zhang H, Bu X, Zhang X, An L, Zhang S, Cao Z, Zhan Q, Yang Y, Cao B, Dai H, Liang L, He J. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China (the China Pulmonary Health [CPH] study): a national cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2018;391(10131):1706–17.

Wang N, Mengersen K, Tong S, Kimlin M, Zhou M, Wang L, Yin P, Xu Z, Cheng J, Zhang Y, Hu W. Short-term association between ambient air pollution and lung cancer mortality. Environ Res. 2019;179(Pt A):108748.

Zhou Y, Ma J, Wang B, Liu Y, Xiao L, Ye Z, Fan L, Wang D, Mu G, Chen W. Long-term effect of personal PM2.5 exposure on lung function: A panel study in China. J Hazard Mater. 2020.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122457

Hvidtfeldt UA, Severi G, Andersen ZJ, Atkinson R, Bauwelinck M, Bellander T, Boutron-Ruault MC, Brandt J, Brunekreef B, Cesaroni G, Chen J, Concin H, Forastiere F, van Gils CH, Gulliver J, Hertel O, Hoek G, Hoffmann B, de Hoogh K, Janssen N, Jockel KH, Jorgensen JT, Katsouyanni K, Ketzel M, Klompmaker JO, Krog NH, Lang A, Leander K, Liu S, Ljungman P, Magnusson P, Mehta AJ, Nagel G, Oftedal B, Pershagen G, Peter RS, Peters A, Renzi M, Rizzuto D, Rodopoulou S, Samoli E, Schwarze PE, Sigsgaard T, Simonsen MK, Stafoggia M, Strak M, Vienneau D, Weinmayr G, Wolf K, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Fecht D. Long-term low-level ambient air pollution exposure and risk of lung cancer - a pooled analysis of 7 European cohorts. Environ Int. 2021;146:106249.

Zhao Q, Kress S, Markevych I, Berdel D, von Berg A, Gappa M, Koletzko S, Bauer CP, Schulz H, Standl M, Heinrich J, Schikowski T. Air pollution during infancy and lung function development into adolescence: The GINIplus/LISA birth cohorts study. Environ Int. 2021;146:106195.

Huls A, Kramer U, Herder C, Fehsel K, Luckhaus C, Stolz S, Vierkotter A, Schikowski T. Genetic susceptibility for air pollution-induced airway inflammation in the SALIA study. Environ Res. 2017;152:43–50.

Song J, Zhu J, Tian G, Li H, Li H, An Z, Jiang J, Fan W, Wang G, Zhang Y, Wu W. Short time exposure to ambient ozone and associated cardiovascular effects: a panel study of healthy young adults. Environ Int. 2020;137:105579.

Yang IA, Fong KM, Zimmerman PV, Holgate ST, Holloway JW. Genetic susceptibility to the respiratory effects of air pollution. Thorax. 2008;63(6):555–63.

Hu X, He L, Zhang J, Qiu X, Zhang Y, Mo J, Day DB, Xiang J, Gong J. Inflammatory and oxidative stress responses of healthy adults to changes in personal air pollutant exposure. Environ Pollut. 2020;263(Pt A):114503.

Huang W, Wang G, Lu SE, Kipen H, Wang Y, Hu M, Lin W, Rich D, Ohman-Strickland P, Diehl SR, Zhu P, Tong J, Gong J, Zhu T, Zhang J. Inflammatory and oxidative stress responses of healthy young adults to changes in air quality during the Beijing Olympics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(11):1150–9.

Zhang H, Han Y, Qiu X, Wang Y, Li W, Liu J, Chen X, Li R, Xu F, Chen W, Yang Q, Fang Y, Fan Y, Wang J, Zhang H, Zhu T. Association of internal exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons with inflammation and oxidative stress in prediabetic and healthy individuals. Chemosphere. 2020;253:126748.

Chatterjee A, Gupta S. The multifaceted role of glutathione S-transferases in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2018;433:33–42.

Ding Z, Wang K, Li J, Tan Q, Tan W, Guo G. Association between glutathione S-transferase gene M1 and T1 polymorphisms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease risk: a meta-analysis. Clin Genet. 2019;95(1):53–62.

Gambichler T, Kreuter A, Susok L, Skrygan M, Rotterdam S, Höxtermann S, Müller M, Tigges C, Altmeyer P, Lahner N. Glutathione-S-transferase T1 genotyping and phenotyping in psoriasis patients receiving treatment with oral fumaric acid esters. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(5):574–80.

Lee EJ, Wong JY, Yeoh PN, Gong NH. Glutathione S transferase-theta (GSTT1) genetic polymorphism among Chinese Malays and Indians in Singapore. Pharmacogenetics. 1995;5(5):332–4.

Wu W, Peden D, Diaz-Sanchez D. Role of GSTM1 in resistance to lung inflammation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53(4):721–9.

Dai X, Bowatte G, Lowe AJ, Matheson MC, Gurrin LC, Burgess JA, Dharmage SC, Lodge CJ. Do Glutathione S-transferase genes modify the link between indoor air pollution and Asthma, Allergies, and Lung Function? A Systematic Review. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2018;18(3):20.

Gilliland FD, Gauderman WJ, Vora H, Rappaport E, Dubeau L. Effects of glutathione-S-transferase M1, T1, and P1 on childhood lung function growth. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(5):710–6.

He JQ, Connett JE, Anthonisen NR, Pare PD, Sandford AJ. Glutathione S-transferase variants and their interaction with smoking on lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(4):388–94.

Imboden M, Downs SH, Senn O, Matyas G, Brandli O, Russi EW, Schindler C, Ackermann-Liebrich U, Berger W, Probst-Hensch NM. Glutathione S-transferase genotypes modify lung function decline in the general population: SAPALDIA cohort study. Respir Res. 2007;8:2.

Wang IJ, Tsai CH, Chen CH, Tung KY, Lee YL. Glutathione S-transferase, incense burning and asthma in children. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(6):1371–7.

Chan-Yeung M, Ho SP, Cheung AH, So LK, Wong PC, Chan KK, Chan JW, Ip MS, Mak JC. Polymorphisms of glutathione S-transferase genes and functional activity in smokers with or without COPD. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11(5):508–14.

Hersoug LG, Brasch-Andersen C, Husemoen LL, Sigsgaard T, Linneberg A. The relationship of glutathione-S-transferases copy number variation and indoor air pollution to symptoms and markers of respiratory disease. Clin Respir J. 2012;6(3):175–85.

Turner S, Francis B, Wani N, Vijverberg S, Pino-Yanes M, Mukhopadhyay S, Tavendale R, Palmer C, Burchard EG, Merid SK, Melen E, Maitland-van DZA, The PICA. Variants in genes coding for glutathione S-transferases and asthma outcomes in children. Pharmacogenomics. 2018;19(8):707–13.

Wang HH, Zhang SC, Wang J, Chen X, Yin H, Huang DY. Combined toxicity of outdoor air pollution on kidney function among adult women in Mianyang City, southwest China. Chemosphere. 2020;2020(238):124603.

Zeng X, Liu D, An Z, Li H, Song J, Wu W. Obesity parameters in relation to lung function levels in a large Chinese rural adult population. Epidemiol Health. 2021;43:e2021047.

Zeng X, Liu D, Zhao X, Chao L, Li Y, Li H, Li W, Gui L, Wu W. Association of bone mineral density with lung function in a Chinese general population: the Xinxiang rural cohort study. BMC Pulm Med. 2019;19:239.

Rebuli ME, Speen AM, Clapp PW, Jaspers I. Novel applications for a noninvasive sampling method of the nasal mucosa. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2017;312(2):L288–96.

Li H, Wu S, Pan L, Xu J, Shan J, Yang X, Dong W, Deng F, Chen Y, Shima M, Guo X. Short-term effects of various ozone metrics on cardiopulmonary function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: Results from a panel study in Beijing. China Environ Pollut. 2018;232:358–66.

Wu S, Wang B, Yang D, Wei H, Li H, Pan L, Huang J, Wang X, Qin Y, Zheng C, Shima M, Deng F, Guo X. Ambient particulate air pollution and circulating antioxidant enzymes: A repeated-measure study in healthy adults in Beijing. China Environ Pollut. 2016;208(Pt A):16–24.

Mu G, Zhou M, Wang B, Cao L, Yang S, Qiu W, Nie X, Ye Z, Zhou Y, Chen W. Personal PM2.5 exposure and lung function: Potential mediating role of systematic inflammation and oxidative damage in urban adults from the general population. Sci Total Environ. 2021;755(Pt 1):142522.

Jiang Y, Niu Y, Xia Y, Liu C, Lin Z, Wang W, Ge Y, Lei X, Wang C, Cai J, Chen R, Kan H. Effects of personal nitrogen dioxide exposure on airway inflammation and lung function. Environ Res. 2019;177:108620.

Edginton S, O’Sullivan DE, King W, Lougheed MD. Effect of outdoor particulate air pollution on FEV1 in healthy adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2019;76(8):583–91.

van Nunen E, Hoek G, Tsai MY, Probst-Hensch N, Imboden M, Jeong A, Naccarati A, Tarallo S, Raffaele D, Nieuwenhuijsen M, Vlaanderen J, Gulliver J, Amaral A, Vineis P, Vermeulen R. Short-term personal and outdoor exposure to ultrafine and fine particulate air pollution in association with blood pressure and lung function in healthy adults. Environ Res. 2021;194:110579.

Zuurbier M, Hoek G, Oldenwening M, Meliefste K, van den Hazel P, Brunekreef B. Respiratory effects of commuters’ exposure to air pollution in traffic. Epidemiology. 2011;22(2):219–27.

Wu S, Deng F, Wang X, Wei H, Shima M, Huang J, Lv H, Hao Y, Zheng C, Qin Y, Lu X, Guo X. Association of lung function in a panel of young healthy adults with various chemical components of ambient fine particulate air pollution in Beijing. China Atmos Environ. 2013;77:873–84.

Adam M, Schikowski T, Carsin AE, Cai Y, Jacquemin B, Sanchez M, Vierkotter A, Marcon A, Keidel D, Sugiri D, Al KZ, Nadif R, Siroux V, Hardy R, Kuh D, Rochat T, Bridevaux PO, Eeftens M, Tsai MY, Villani S, Phuleria HC, Birk M, Cyrys J, Cirach M, de Nazelle A, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Forsberg B, de Hoogh K, Declerq C, Bono R, Piccioni P, Quass U, Heinrich J, Jarvis D, Pin I, Beelen R, Hoek G, Brunekreef B, Schindler C, Sunyer J, Kramer U, Kauffmann F, Hansell AL, Kunzli N, Probst-Hensch N. Adult lung function and long-term air pollution exposure. ESCAPE: a multicentre cohort study and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(1):38–50.

Fan Z, Pun VC, Chen XC, Hong Q, Tian L, Ho SS, Lee SC, Tse LA, Ho KF. Personal exposure to fine particles (PM2.5) and respiratory inflammation of common residents in Hong Kong. Environ Res. 2018;164:24–31.

Li W, Wilker EH, Dorans KS, Rice MB, Schwartz J, Coull BA, Koutrakis P, Gold DR, Keaney JJ, Lin H, Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ, Mittleman MA. Short-Term Exposure to Air Pollution and Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress: The Framingham Heart Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(5):e002742.

Zhang S, Huo X, Zhang Y, Huang Y, Zheng X, Xu X. Ambient fine particulate matter inhibits innate airway antimicrobial activity in preschool children in e-waste areas. Environ Int. 2019;123:535–42.

Zhu H, Wu Y, Kuang X, Liu H, Guo Z, Qian J, Wang D, Wang M, Chu H, Gong W, Zhang Z. Effect of PM2.5 exposure on circulating fibrinogen and IL-6 levels: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chemosphere. 2021;271:129565.

Li Z, Liu Q, Xu Z, Guo X, Wu S. Association between short-term exposure to ambient particulate air pollution and biomarkers of oxidative stress: a meta-analysis. Environ Res. 2020;191:110105.

Chuang KJ, Chan CC, Su TC, Lee CT, Tang CS. The effect of urban air pollution on inflammation, oxidative stress, coagulation, and autonomic dysfunction in young adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(4):370–6.

He L, Hu X, Gong J, Day D, Xiang J, Mo J, Zhang Y, Zhang J. Endogenous melatonin mediation of systemic inflammatory responses to ozone exposure in healthy adults. Sci Total Environ. 2020;749:141301.

Gruzieva O, Merid SK, Gref A, Gajulapuri A, Lemonnier N, Ballereau S, Gigante B, Kere J, Auffray C, Melen E, Pershagen G. Exposure to traffic-related air pollution and serum inflammatory cytokines in children. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(6):67007.

Steinvil A, Kordova-Biezuner L, Shapira I, Berliner S, Rogowski O. Short-term exposure to air pollution and inflammation-sensitive biomarkers. Environ Res. 2008;106(1):51–61.

Lee H, Myung W, Jeong BH, Choi H, Jhun BW, Kim H. Short- and long-term exposure to ambient air pollution and circulating biomarkers of inflammation in non-smokers: a hospital-based cohort study in South Korea. Environ Int. 2018;119:264–73.

Ward-Caviness CK. A review of gene-by-air pollution interactions for cardiovascular disease, risk factors, and biomarkers. Hum Genet. 2019;138(6):547–61.

Bowatte G, Lodge CJ, Perret JL, Matheson MC, Dharmage SC. Interactions of GST Polymorphisms in Air Pollution Exposure and Respiratory Diseases and Allergies. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2016;16(12):85.

Chahine T, Baccarelli A, Litonjua A, Wright RO, Suh H, Gold DR, Sparrow D, Vokonas P, Schwartz J. Particulate air pollution, oxidative stress genes, and heart rate variability in an elderly cohort. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(11):1617–22.

Piacentini S, Polimanti R, Moscatelli B, Re MA, Fuciarelli R, Manfellotto D, Fuciarelli M. Glutathione S-transferase gene polymorphisms and air pollution as interactive risk factors for asthma in a multicentre Italian field study: a preliminary study. Ann Hum Biol. 2010;37(3):427–39.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number: 81573112; 81961128031), Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (202300410313), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant number: 2016YFC0900803).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiang Zeng: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing—original draft. Ge Tian: Investigation, Data curation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Formal analysis. Jingfang Zhu: Investigation, Methodology, Validation. Fuyun Yang: Investigation, Methodology, Validation. Rui Zhang: Investigation, Methodology, Validation. Huijun Li: Investigation, Methodology, Validation. Zhen An: Investigation, Methodology, Validation. Jie Song: Investigation, Methodology, Validation. Jing Jiang: Investigation, Methodology, Validation. Dongling Liu: Investigation, Methodology, Validation. Weidong Wu: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing—review & editing, Project administration, Resources, Validation. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, X., Tian, G., Zhu, J. et al. Air pollution associated acute respiratory inflammation and modification by GSTM1 and GSTT1 gene polymorphisms: a panel study of healthy undergraduates. Environ Health 22, 14 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-022-00954-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-022-00954-9