Abstract

Background

Indigenous peoples of the United States disproportionately experience chronic diseases associated with poor nutrition, including obesity and diabetes. While chronic disease related health disparities among Indigenous people are well documented, it is unknown whether interventions adequately address these health disparities. In addition, it is unknown whether and to what extent interventions are culturally adapted or tailored to the unique culture, worldview and nutrition environments of Indigenous people. The aim of this review was to identify and characterize nutrition interventions conducted with Indigenous populations in the US, and to determine whether and to what degree communities are involved in intervention design, implementation and evaluation.

Methods

Peer-reviewed articles were identified using MEDLINE. Articles included were published in English in a refereed journal between 2000 and 2015, reported on a diet-related intervention in Indigenous populations in the US, and reported outcome data. Data extracted were program objectives and activities, target population, geographic region, formative research to inform design and evaluation, partnership, capacity building, involvement of the local food system, and outcomes. Narrative synthesis of intervention characteristics and the degree and type of community involvement was performed.

Results

Of 1060 records identified, 49 studies were included. Overall, interventions were successful in producing changes in knowledge, behavior or health (79%). Interventions mostly targeted adults in the Western region and used a pre-test, post-test design. Involvement of communities in intervention design, implementation, and evaluation varied from not at all to involvement at all stages. Of programs reporting significant changes in outcomes, more than half used at least three strategies to engage communities. However, formative research to inform the evaluation was not performed to a great degree, and fewer than half of the programs identified described involvement of the local food system.

Conclusions

The extent of use of strategies to promote community engagement in programs reporting significant outcomes is notable. In planning interventions in Indigenous groups, researchers should consider ways to involve the community in intervention design, execution and evaluation. There is a particular need for studies focused on Indigenous youth in diverse regions of the US to further address diet-related chronic conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Indigenous peoples of the United States disproportionately experience chronic diseases associated with poor nutrition, including obesity and diabetes. American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) preschool children have the highest prevalence of obesity compared to other racial/ ethnic groups (37.0% among AIAN compared to 17.4% among non-Hispanic whites) [1]. Disparities persist into adulthood, and recent reports indicate that the prevalence of obesity among AIAN adults is approximately 80% higher than among non-Hispanic whites and Asians [2]. Furthermore, although the prevalence of obesity appears to have leveled off in other ethnic and racial groups, the prevalence continues to rise among AIAN people [3, 4]. Consistent with obesity rate, the prevalence of diabetes is considerably higher in AIAN (17.9%) than in non-Hispanic whites (7.9%) [5].

While chronic disease related health disparities among AIAN people are well documented, it is unknown whether interventions adequately address these health disparities. In addition, it is unknown whether and to what extent interventions are culturally adapted or tailored to the unique culture, worldview and nutrition environments of AIAN people. Genuine and equitable partnerships between researchers and AIAN communities are critical to ensuring that interventions are relevant. Community based participatory research (CBPR) is considered best practice for conducting research with AIAN communities [6, 7]. Using a CBPR approach that draws on the traditional knowledge of communities can engender strength-based interventions that reinforce cultural continuity and have broad positive impacts. For example, programs seeking to strengthen the traditional food system have the potential to address high prevalence of chronic disease in addition to promoting food sovereignty. These traditional practices also provide a foundation for cultural identity, a basis for social support networks, and assist Indigenous Peoples in gaining greater autonomy [8].

While involvement of the community at every step of the process in intervention planning and implementation in Indigenous groups has been widely noted to be important in promoting adequate dietary intake, not all programs have involved engagement with community members. Examining and characterizing interventions that have involved community engagement to various degrees may prove useful for researchers and educators planning to implement programs in Indigenous communities. The primary objectives of this systematic review were to: 1) Identify and characterize nutrition interventions conducted with Indigenous populations in the United States; and 2) To determine whether and to what degree communities are involved in the design, implementation, and evaluation of the intervention.

Methods

Peer-reviewed journal articles were identified using the online database MEDLINE.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included in the review, research articles had to 1) be published in a refereed journal between 2000 and 2015; 2) report on a diet-related program or intervention conducted in an Indigenous population in the United States; 3) report outcome data. Studies that were reported in a language other than English, reported on process data only, and review papers were not included.

Search strategy

The following two overarching concepts were identified to guide selection of search terms and phrases based on the review objectives: Indigenous populations and chronic disease prevention/health promotion. For the first key concept, related terms and phrases identified were: ‘Hawaii/ethnology,’ ‘Native Hawaiian,’ ‘Indians, North American,’ ‘American Indian,’ ‘Native American,’ ‘Native Alaskan,’ ‘Oceanic Ancestry Group/ethnology.’ For the second key concept, search terms and phrases were as follows: ‘diabetes mellitus/education,’ ‘diabetes mellitus/prevention and control,’ ‘chronic disease/prevention and control,’ ‘nutritional sciences/education,’ ‘obesity/prevention and control,’ ‘health promotion,’ ‘overweight/prevention and control,’ ‘cardiovascular diseases/prevention and control,’ ‘wellness,’ and ‘intervention.’ Boolean operators such as AND and OR were used to link search terms.

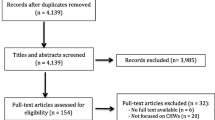

Using the search terms, one researcher (JB) identified abstracts for review. Referencing the inclusion criteria, the same researcher examined the abstracts and excluded studies not meeting the requirements for inclusion. The same procedure was followed with the full papers identified using the abstracts remaining. Finally, for all full papers included, a search was conducted for other papers reporting on the same study by searching for the title of the intervention and examining the references in each paper. This search was conducted to address the fact that many papers reporting outcomes do not report on the steps involving community engagement. While one goal of the review was to characterize interventions and thus gauge the effectiveness of programs through outcomes reported, it was also imperative to capture community involvement through examination of all papers related to each study. Figure 1 illustrates the search strategy used for this review.

Data extraction

After obtaining consensus on the abstraction tool, two researchers (JB, AB) piloted the tool on two studies to reach agreement on the procedures for data abstraction. One researcher (JB) then conducted a systematic review of full studies identified and completed the abstraction table. Data entered in the abstraction table included the following: study objectives, target population/inclusion criteria, study design, study setting (city, state), study duration, sample size, response rate, intervention (focus and main activities of the program), outcome variables, measures utilized, involvement of the community in the design, implementation, and evaluation of the intervention (formative research to inform design and evaluation, partnership, community capacity building, involvement of local food system), treatment length/follow up, drop out, results, main implications, and limitations.

Data synthesis

Table 1 contains a list and description of the 49 studies identified in the literature search. Within these 49 studies, there were 39 distinct programs, given that the outcomes of some programs were described in multiple publications.

Quality appraisal of studies

Study quality was assessed using the Effective Public Health Policy Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool. The EPHPP Quality Assessment Tool provides criteria to evaluate studies on the basis of selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, withdraws and dropouts, intervention integrity, and analysis. Each criterion is scored numerically according to the guidelines as strong (score = 1), moderate (score = 2), or weak (score = 3). Subsequently, the entire article is rated as strong (no weak ratings), moderate (one weak rating), or weak (two or more weak ratings).

Results

Program objectives

Program objectives varied. Four focused on reducing BMI, one focused on increasing physical activity, five focused on improving diet or food behaviors, six focused on improving knowledge/awareness and/or self-efficacy, five focused on improving other health outcomes (e.g., Hgb A1c, blood pressure, cholesterol), and 18 studies had multiple objectives.

Program activities

All programs had a nutrition education component. Seven also focused on changes to the physical environment (Table 1). For example, an obesity prevention trial in American Indian children incorporated changes to foods served in the school setting to reduce calories [9]. In another study in Native American high school youth, an existing room in the high school was remodeled into a fitness center [10]. Twenty-nine programs included a physical activity component in addition to the dietary component.

Target populations

Sixteen programs focused on groups suffering from a chronic condition, such as overweight/obesity or diabetes. Twenty-four programs focused exclusively on adults, seven programs focused exclusively on children, and seven programs included a wide age range. Nineteen studies focused exclusively on American Indian populations. Seven studies included AI and/or AN in addition to one or more ethnic groups. None focused on Alaska Native populations exclusively. Information on the target population is reported in Table 1.

Geographic region

With regards to geographic region, two programs were conducted in the Northeast, six in the Midwest, three in the South, 22 in the Western region, and six in more than one region of the US.

Formative research to inform design

Twenty-five programs reported conducting formative research to inform the design of the intervention, although the nature and duration of the formative research varied. While in some cases investigators relied on literature review or review of existing data to inform design, in most cases, the community was directly involved in this step. Formative activities included interviewing or conducting focus groups with members of the target population for guidance regarding the content, format, and method of delivery of the intervention, pilot testing of the intervention in the community, and review of the curriculum by the community. For example, the Strong in Body and Spirit program in Native Americans involved focus group sessions in the community that allowed members to express their desire for inclusion of traditional foods and values [11]. The types of formative research used to inform design of the intervention in each study are displayed in Table 2.

Formative research to inform evaluation

Five programs identified included formative research to inform evaluation of the intervention. These activities included collaborative work of the research team with the community to identify outcome measures, as well as examination of evaluation instruments by members of the target population to ensure relevance. For example, for the Healthy Living in Two Worlds project conducted in urban Native youth, a draft of the instrument to be used to assess knowledge, attitudes and behaviors related to tobacco use, dietary practices and physical activities was evaluated by several Haudenosaunee youth to insure that the questions were clear and meaningful to this particular population [12]. The types of formative research used to inform evaluation of the intervention in each study are displayed in Table 3.

Partnership

Twenty-eight programs involved a partnership between researchers and the community. Such partnerships involved collaboration with the target population on data collection, collaboration with local organizations or establishments, development of a community action plan with the target population, delivery of the intervention by members of the target population, holding regular meetings with the target population, and collaboration with the tribal review board or ethics committee. For example, in a type 2 diabetes prevention intervention in Native American communities, program staff networked with local agencies to share information and resources to inform the intervention [13]. The types of partnerships formed in each study are displayed in Table 4.

Capacity building

Twenty-one programs included some aspect of capacity building among project staff and community members in their programs. Examples of capacity building included training community members to perform health-promoting practices, use of “train the trainer” sessions, joint development of a community action plan, formation of local working groups, and promotion of career development of project staff. For example, several studies used community peer educators to deliver lessons that formed part of the intervention [14, 15]. The types of capacity building that were part of each study are displayed in Table 5.

Involvement of local food system

Sixteen programs incorporated some aspect of the local food system into the intervention. This included involving local food service or local food retailers in the intervention, as well as incorporating local foods into the educational materials and/or activities programs. For example, in an after-school intervention of urban Native American youth, discussion of the importance and roles of traditional foods of the group under study formed part of lessons provided [16]. The types of involvement of the local food system in each study are displayed in Table 6.

Outcomes

Thirty–one programs of the 39 programs (79%) identified reported significant changes in knowledge, behavior or health (Table 1). In terms of the degree of community involvement in the studies reporting significant changes in outcomes, all except one program included at least one of the five strategies examined in this review regarding community engagement, and 19 used at least three out of the five strategies (Table 1). For example, the Cancer 101 program employed formative research to inform the design of the program in working with tribal health directors to review the curriculum, demonstrated partnership with organizations that had established relationships with tribal communities and involved capacity building in the form of train the trainer sessions [17]. In further examining the studies reporting significant results, five were RCTs, 24 were pre-post studies, one had a multiple cross-sectional design, and one was a retrospective study.

Study quality

Twelve studies were rated as strong, 13 studies were rated as moderate, and 14 studies were rated as weak according to the EPHPP Quality Assessment Tool.

Discussion

Results of the current literature review yielded research studies conducted with a variety of objectives in diverse Indigenous groups throughout the US. Overall, interventions were successful in producing changes in knowledge, behavior or health. The degree to which communities were involved in the design, implementation, and evaluation of the intervention varied from not at all to involvement at all stages. Of the programs reporting significant changes in outcome measures, more than half used at least three strategies to engage communities. The extent of use of strategies to promote community engagement in programs reporting significant outcomes is notable.

While formative research to inform the design of the interventions was performed in most studies, formative research to inform the evaluation was not performed to a great degree, with only six programs identified including this step. In some of these cases, researchers worked with the community to determine what outcomes should be measured, a process that enhances the program’s alignment with traditional values. In particular, following an indigenous evaluation framework, as described by LeFrance and colleagues, ensures that programs pay sufficient attention to the cultural context in which behaviors arise, thereby increasing the potential success of interventions [18]. In other cases, members of the target population provided input on the content of evaluation tools and participated in pilot testing. Previous research has revealed the importance of this step and has outlined procedures that may be used to determine face validity of instruments [19], as well as other procedures that should be conducted to evaluate the psychometric properties of evaluation tools [20]. It is essential that evaluation tools are designed in collaboration with the target audience to ensure relevance [20]. Given that very few studies identified in this review involved formative research to inform evaluation, it is possible that not all relevant outcomes were reported. While results were often presented in terms of changes in weight and diet, there may be other outcomes such as cultural connectedness that may be important for the communities in question but were not measured.

Fewer than half of the programs identified described involvement of the local food system. In further seeking to promote health in Indigenous communities, incorporation of local foods is an important consideration. Working in concert with local food retailers or other establishments may allow for the inclusion of traditional foods in the intervention. In communities in which people identify themselves with their culture and natural environment, use of traditional food systems to improve health builds community support and engagement for holistic health and well-being [21]. Factors contributing to obesity and diabetes in Indigenous people are complex, and are rooted in dietary Westernization that leads to significant changes in food sources and nutrient intake [22]. In Indigenous communities, participating in the traditional food system is linked to higher diet quality, lower levels of chronic disease risk factors, lower levels of stress and overall well-being. The traditional diet of Yup’ik People in Southwestern Alaska, for example, is rich in vitamin D, vitamin A, vitamin E, iron, and n-3 fatty acids through inclusion of foods such as fatty fish, fish roe, seal oil and wild game [22]. Similarly, the traditional diet of Native Hawaiians has been found to be high in fiber, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and low in fat and cholesterol [23]. Over the past century, Indigenous food systems have been compromised as a result of social, economic, political and environmental pressures [24]. The consequences of the transition away from nutrient-rich traditional food in Indigenous communities include shifts in nutrients intake, obesity and associated diet-related chronic conditions [25,26,27]. In a study of Pima Indians in Arizona, for example, intake of complex carbohydrate, dietary fiber, insoluble fiber, vegetable proteins and the proportion of total calories from complex carbohydrate and vegetable proteins were significantly higher in the Indian than in the Anglo diet [28]. Intervention activities must work in concert with the local cultural and social settings, local personnel and local sources of food [21].

The majority of programs were carried out in the Western region. Of note, of the studies conducted in this region, relatively few were focused on populations in Alaska and Hawai’i. As Indigenous groups in these states face health disparities, future studies may further focus on these geographic areas. Among Native Hawaiians, for example, the prevalence of chronic diseases constituting the leading causes of death in the U.S.—heart disease, cancer, and diabetes—is notably high [29]. Rates of diet-related chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease are also high in Alaska Natives [30]. Other researchers have pointed to the need for individual-level interventions for behaviors related to obesity in groups such as Native Hawaiians [29].

Also of note, most programs focused exclusively on adults. As particular nutrition-related burdens fall on youth, children continue to be an important target group in further addressing issues related to diet in Indigenous groups. According to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 17% of children and adolescents in the U.S. were obese in 2011–2014 [31]. Previous studies indicate that the diet quality of children and adolescents in the U.S. falls short of the recommendations, and that diet quality may be improved by increased intake of foods such as vegetables, whole grains and seafood [32]. Good nutrition is essential for child growth and development, as well as for maintenance of a healthy weight [33].

Ten of the interventions identified were randomized controlled trials, and half of these reported significant results. Most studies used a pre-test, post-test design. Without a control group, such studies do not provide the same level of evidence as the RCT and do not allow conclusions of the same caliber to be drawn [34]. However, given that research in Indigenous populations may be performed in small, geographically dispersed samples, it may not always be feasible to conduct a RCT. Studies with a pre-test, post-test design may provide evidence to inform additional studies in the population of interest. Of note, there were a number of studies rate as “weak” with regards to study quality. These ratings reflected issues such as failure to report withdrawals and drop-outs, as well as lack of assessment of validity and reliability of data collection tools. Failure to report withdrawals and dropouts leads to difficulty in determining the degree to which participants engaged in the intervention and the effects of the program, as evaluation of all participants enrolled in the program may not have been possible. In other cases, it was not possible to ascertain whether the outcome assessors were aware of the intervention or exposure status of participants or if the study participants were aware of the research question. These issues may have compromised study results to varying degrees. If, for example, outcome assessors were aware of the intervention or exposure status of participants, this may have led them to alter their behavior toward participants or perform measurements differently in the two groups. In cases in which less than 100% of participants received the allocated intervention, it is possible that there may have been systematic differences between those who completed the intervention and those who did not, compromising the results of the study.

With regards to program activities, relatively few programs involved changes to the physical environment. However, of those that did, all found significant results, and five out of the seven studies also involved used of at least three strategies to engage communities. Other researchers have noted the need to design interventions at multiple levels, including individual, social environmental, physical environmental, and macrosystem [35]. While all of the programs identified in this review had a nutrition education component, a change in health outcomes may not result without concomitant environmental changes. In planning future interventions, this is an important consideration.

Limitations

While not all studies made use of the strategies identified in this review to engage communities, it should be noted that not all studies focused exclusively on Indigenous populations. In some cases, the target population was comprised of both Indigenous people and members of other groups. In these instances, it may not have been possible or reasonable to use some of the strategies identified, such as incorporating traditional foods into the intervention. This should be taken into account in examining results. Further, only one database was used to identify articles to include in the review, and gray literature was not examined. Thus, it is possible that some relevant articles may not have been located.

Conclusions

Interventions performed in Indigenous groups in the US were generally successful in producing changes in knowledge, behavior or health. Interventions mostly targeted adults in the Western region and used a pre-test, post-test design. Of the nutrition interventions reporting significant changes in outcome measures, more than half involved notable engagement of communities. The degree of use of strategies to promote community engagement in programs reporting significant outcomes is notable. However, formative research to inform the evaluation was not performed to a great degree, and fewer than half of the programs identified described involvement of the local food system. In planning interventions in Indigenous groups, researchers may consider the range of ways in which the community may be involved in the design, execution and evaluation of the intervention based on the studies reviewed here. Such involvement is likely to improve the success of these initiatives. There is a particular need for studies focused on Indigenous youth in diverse regions of the US to further address diet-related chronic conditions.

Abbreviations

- AI:

-

American Indian

- AN:

-

Alaska Natives

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CBPR:

-

Community-based participatory research

- CHW:

-

Community health worker

- NA:

-

Native American

- NH:

-

Native Hawaiian

- NHOPI:

-

Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

References

Anderson SE, Whitaker RC. Prevalence of obesity among US preschool children in different racial and ethnic groups. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(4):344–8.

Schoenborn CA, Adams PF, Peregoy JA. Health behaviors of adults: United States, 2008-2010. Vital Health Stat 10. 2013;(257):1–184.

Jernigan VB, Duran B, Ahn D, Winkleby M. Changing patterns in health behaviors and risk factors related to cardiovascular disease among American Indians and Alaska natives. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(4):677–83.

Madsen KA, Weedn AE, Crawford PB. Disparities in peaks, plateaus, and declines in prevalence of high BMI among adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):434–42.

Blackwell DL, Lucas JW, Clarke TC. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2012. Vital Health Stat 10. 2014;(260):1–161.

Rasmus SM. Indigenizing CBPR: evaluation of a community-based and participatory research process implementation of the Elluam Tungiinun (towards wellness) program in Alaska. Am J Community Psychol. 2014;54(1–2):170–9.

Teufel-Shone NI. Promising strategies for obesity prevention and treatment within American Indian communities. J Transcult Nurs. 2006;17(3):224–9.

Egeland GM, Harrison GG, Kuhnlein HV, Erasmus B, Spigelski D, Burlingame B. Health disparities: promoting Indigenous Peoples' health through traditional food systems and self-determination. In: Indigenous peoples' food systems and well-being: interventions and policies for healthy communities; 2013. p. 9–22.

Story M, Hannan PJ, Fulkerson JA, Rock BH, Smyth M, Arcan C, Himes JH. Bright start: description and main outcomes from a group-randomized obesity prevention trial in American Indian children. Obesity. 2012;20(11):2241–9.

Ritenbaugh C, Teufel-Shone NI, Aickin MG, Joe JR, Poirier S, Dillingham DC, Johnson D, Henning S, Cole SM, Cockerham D. A lifestyle intervention improves plasma insulin levels among native American high school youth. Prev Med. 2003;36(3):309–19.

Gilliland SS, Azen SP, Perez GE, Carter JS. Strong in body and spirit: lifestyle intervention for native American adults with diabetes in New Mexico. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(1):78–83.

Weaver HN, Jackson KF. Healthy living in two worlds: testing a wellness curriculum for urban native youth. Child Adolesc Social Work J. 2010;27(3):231–44.

Murphy S, Wilson C. Breastfeeding promotion: a rational and achievable target for a type 2 diabetes prevention intervention in native American communities. J Hum Lact. 2008;24(2):193–8.

Mau MK, Keawe'aimoku Kaholokula J, West MR, Leake A, Efird JT, Rose C, Palakiko DM, Yoshimura S, Kekauoha PB, Gomes H. Translating diabetes prevention into native Hawaiian and Pacific islander communities: the PILI 'Ohana pilot project. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2010;4(1):7–16.

Harvey-Berino J, Rourke J. Obesity prevention in preschool native-american children: a pilot study using home visiting. Obes Res. 2003;11(5):606–11.

Rinderknecht K, Smith C. Social cognitive theory in an after-school nutrition intervention for urban native American youth. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2004;36(6):298–304.

Hill TG, Briant KJ, Bowen D, Boerner V, Vu T, Lopez K, Vinson E. Evaluation of Cancer 101: an educational program for native settings. J Cancer Educ. 2010;25(3):329–36.

LaFrance J, Nichols R, Kirkhart KE. Culture writes the script: on the centrality of context in indigenous evaluation. N Dir Eval. 2012;2012(135):59–74.

Banna JC, Vera Becerra LE, Kaiser LL, Townsend MS. Using qualitative methods to improve questionnaires for Spanish speakers: assessing face validity of a food behavior checklist. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(1):80–90.

Townsend MS. Evaluating food stamp nutrition education: process for development and validation of evaluation measures. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2006;38(1):18–24.

Kuhnlein HV, Burlingame B, Erasmus B, Spigelski D. Why do indigenous Peoples' food and nutrition interventions for health promotion and policy need special consideration? In: Indigenous peoples' food systems and well-being: interventions and policies for healthy communities; 2013. p. 3–8.

Bersamin A, Zidenberg-Cherr S, Stern JS, Luick BR. Nutrient intakes are associated with adherence to a traditional diet among Yup'ik Eskimos living in remote Alaska native communities: the CANHR study. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2007;66(1):62–70.

Blaisdell R. Historical and cultural aspects of native Hawaiian health. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press; 1989.

Turner NJ, Plotkin M, Kuhnlein HV, Erasmus B, Spigelski D, Burlingame B. Global environmental challenges to the integrity of Indigenous Peoples' food systems. In: Communities Ipfsaw-biapfh, editor. Indigenous peoples' food systems & well-being: interventions & policies for healthy communities; 2013. p. 23–38.

Egeland GM, Johnson-Down L, Cao ZR, Sheikh N, Weiler H. Food insecurity and nutrition transition combine to affect nutrient intakes in Canadian arctic communities. J Nutr. 2011;141(9):1746–53.

Johnson-Down LM, Egeland GM. How is nutrition transition affecting dietary adequacy in Eeyouch (Cree) adults of northern Quebec, Canada? Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2013;38(3):300–5.

Reeds J, Mansuri S, Mamakeesick M, Harris SB, Zinman B, Gittelsohn J, Wolever TM, Connelly PW, Hanley A. Dietary patterns and type 2 diabetes mellitus in a first nations community. Can J Diabetes. 2016;40(4):304–10.

Williams DE, Knowler WC, Smith CJ, Hanson RL, Roumain J, Saremi A, Kriska AM, Bennett PH, Nelson RG. The effect of Indian or Anglo dietary preference on the incidence of diabetes in pima Indians. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(5):811–6.

Asian and Pacific Islander American Health Forum: Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Health Disparities; 2010. Available at: https://www.apiahf.org/resource/native-hawaiian-and-pacific-islander-health-disparities/.

Jolly SE, Howard BV, Umans JG. Cardiovascular Disease Among Alaska Native Peoples. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2013;7(6):438–45.

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Flegal KM. Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2011-2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;(219):1–8.

United States Department of Agriculture Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion. Diet Quality of Children Age 2–17 Years as Measured by the Healthy Eating index-2010. Nutrition Insight 52. 2013.

Institute of Medicine Committee on Prevention of Obesity in C, Youth: The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In: Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. edn. Edited by Koplan JP, Liverman CT, Kraak VI. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) National Academy of Sciences.; 2005.

Willett W. Nutritional epidemiology. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013.

Baranowski T, Perry, C.L., Parcel, G.S. : How Individuals, Environments, and Health Behavior Interact. In: Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 3rd edn. Glanz K, Rimer, B.K., Lewis, F.M. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002: 165–184.

Arcan C, Hannan PJ, Himes JH, Fulkerson JA, Rock BH, Smyth M, Story M. Intervention effects on kindergarten and first-grade teachers' classroom food practices and food-related beliefs in American Indian reservation schools. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(8):1076–83.

Bachar JJ, Lefler LJ, Reed L, McCoy T, Bailey R, Bell R. Cherokee choices: a diabetes prevention program for American Indians. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(3):A103.

Wagner EH, Wickizer TM, Cheadle A, Psaty BM, Koepsell TD, Diehr P, Curry SJ, Von Korff M, Anderman C, Beery WL, et al. The Kaiser Family Foundation Community health promotion grants program: findings from an outcome evaluation. Health Serv Res. 2000;35(3):561–89.

Beckham S, Bradley S, Washburn A, Taumua T. Diabetes management: utilizing community health workers in a Hawaiian/Samoan population. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(2):416–27.

Mayer-Davis EJ, Sparks KC, Hirst K, Costacou T, Lovejoy JC, Regensteiner JG, Hoskin MA, Kriska AM, Bray GA. Dietary intake in the diabetes prevention program cohort: baseline and 1-year post randomization. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14(10):763–72.

Wing RR, Hamman RF, Bray GA, Delahanty L, Edelstein SL, Hill JO, Horton ES, Hoskin MA, Kriska A, Lachin J, et al. Achieving weight and activity goals among diabetes prevention program lifestyle participants. Obes Res. 2004;12(9):1426–34.

Mendenhall TJ, Berge JM, Harper P, GreenCrow B, LittleWalker N, WhiteEagle S, BrownOwl S. The family education diabetes series (FEDS): community-based participatory research with a midwestern American Indian community. Nurs Inq. 2010;17(4):359–72.

Buller DB, Woodall WG, Zimmerman DE, Slater MD, Heimendinger J, Waters E, Hines JM, Starling R, Hau B, Burris-Woodall P, et al. Randomized trial on the 5 a day, the Rio Grande way website, a web-based program to improve fruit and vegetable consumption in rural communities. J Health Commun. 2008;13(3):230–49.

Bradley S, Beckham S, Washburn A. The Hawai'i community resource obesity project: results from the lifestyle enhancement program. Hawaii Med J. 2009;68(4):80–4.

Gittelsohn J, Vijayadeva V, Davison N, Ramirez V, Cheung LW, Murphy S, Novotny R. A food store intervention trial improves caregiver psychosocial factors and children's dietary intake in Hawaii. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 2010;18(Suppl 1):S84–90.

Carrel A, Meinen A, Garry C, Storandt R. Effects of nutrition education and exercise in obese children: the Ho-Chunk Youth Fitness Program. WMJ. 2005;104(5):44–7.

Brown B, Noonan C, Harris KJ, Parker M, Gaskill S, Ricci C, Cobbs G, Gress S. Developing and piloting the journey to native youth health program in Northern Plains Indian communities. Diabetes Educ. 2013;39(1):109–18.

Gellert KS, Aubert RE, Mikami JS. Ke 'Ano Ola: Moloka'i's community-based healthy lifestyle modification program. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(5):779–83.

Benyshek DC, Chino M, Dodge-Francis C, Begay TO, Jin H, Giordano C. Prevention of type 2 diabetes in urban American Indian/Alaskan native communities: the life in BALANCE pilot study. J Diabetes Mellitus. 2013;3(4):184–91.

Kattelmann KK, Conti K, Ren C. The medicine wheel nutrition intervention: a diabetes education study with the Cheyenne River Sioux tribe. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(9):1532–9.

Burden RW, Kumar RN, Phillips DL, Borrego ME, Galloway JM. Hyperlipidemia in native Americans: evaluation of lipid management through a cardiovascular risk reduction program. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2002;42(4):652–5.

Mau MK, Glanz K, Severino R, Grove JS, Johnson B, Curb JD. Mediators of lifestyle behavior change in native Hawaiians: initial findings from the native Hawaiian diabetes intervention program. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(10):1770–5.

Gittelsohn J, Kim EM, He S, Pardilla M. A food store-based environmental intervention is associated with reduced BMI and improved psychosocial factors and food-related behaviors on the Navajo nation. J Nutr. 2013;143(9):1494–500.

Sinclair KA, Makahi EK, Shea-Solatorio C, Yoshimura SR, Townsend CK, Kaholokula JK. Outcomes from a diabetes self-management intervention for native Hawaiians and Pacific people: Partners in Care. Ann Behav Med. 2013;45(1):24–32.

Caballero B, Clay T, Davis SM, Ethelbah B, Rock BH, Lohman T, Norman J, Story M, Stone EJ, Stephenson L, et al. Pathways: a school-based, randomized controlled trial for the prevention of obesity in American Indian schoolchildren. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(5):1030–8.

Gittelsohn J, Evans M, Helitzer D, Anliker J, Story M, Metcalfe L, Davis S, Iron CP. Formative research in a school-based obesity prevention program for native American school children (Pathways). Health Educ Res. 1998;13(2):251–65.

Cunningham-Sabo L, Snyder MP, Anliker J, Thompson J, Weber JL, Thomas O, Ring K, Stewart D, Platero H, Nielsen L. Impact of the Pathways food service intervention on breakfast served in American-Indian schools. Prev Med. 2003;37(6 Pt 2):S46–54.

Davis SM, Clay T, Smyth M, Gittelsohn J, Arviso V, Flint-Wagner H, Rock BH, Brice RA, Metcalfe L, Stewart D, et al. Pathways curriculum and family interventions to promote healthful eating and physical activity in American Indian schoolchildren. Prev Med. 2003;37(6 Pt 2):S24–34.

Himes JH, Ring K, Gittelsohn J, Cunningham-Sabo L, Weber J, Thompson J, Harnack L, Suchindran C. Impact of the Pathways intervention on dietary intakes of American Indian schoolchildren. Prev Med. 2003;37(6 Pt 2):S55–61.

Stevens J, Story M, Ring K, Murray DM, Cornell CE, Juhaeri GJ. The impact of the Pathways intervention on psychosocial variables related to diet and physical activity in American Indian schoolchildren. Prev Med. 2003;37(6 Pt 2):S70–9.

Stevens J, Cornell CE, Story M, French SA, Levin S, Becenti A, Gittelsohn J, Going SB, Reid R. Development of a questionnaire to assess knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors in American Indian children. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(4 Suppl):773s–81s.

Stone EJ, Norman JE, Davis SM, Stewart D, Clay TE, Caballero B, Lohman TG, Murray DM. Design, implementation, and quality control in the Pathways American-Indian multicenter trial. Prev Med. 2003;37(6 Pt 2):S13–23.

Story M, Snyder MP, Anliker J, Weber JL, Cunningham-Sabo L, Stone EJ, Chamberlain A, Ethelbah B, Suchindran C, Ring K. Changes in the nutrient content of school lunches: results from the Pathways study. Prev Med. 2003;37(6 Pt 2):S35–45.

Kaholokula JK, Wilson RE, Townsend CK, Zhang GX, Chen J, Yoshimura SR, Dillard A, Yokota JW, Palakiko DM, Gamiao S, et al. Translating the diabetes prevention program in native Hawaiian and Pacific islander communities: the PILI 'Ohana project. Transl Behav Med. 2014;4(2):149–59.

Kaholokula JK, Kekauoha P, Dillard A, Yoshimura S, Palakiko DM, Hughes C, Townsend CK. The PILI 'Ohana project: a community-academic partnership to achieve metabolic health equity in Hawai'i. Hawai'i J Med Public Health. 2014;73(12 Suppl 3):29–33.

Richards J, Mousseau A. Community-based participatory research to improve preconception health among Northern Plains American Indian adolescent women. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 2012;19(1):154–85.

Jiang L, Manson SM, Beals J, Henderson WG, Huang H, Acton KJ, Roubideaux Y. Translating the diabetes prevention program into American Indian and Alaska native communities: results from the special diabetes program for Indians diabetes prevention demonstration project. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(7):2027–34.

Moore K, Jiang L, Manson SM, Beals J, Henderson W, Pratte K, Acton KJ, Roubideaux Y. Case management to reduce cardiovascular disease risk in American Indians and Alaska natives with diabetes: results from the special diabetes program for Indians healthy heart demonstration project. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):e158–64.

Jernigan VB. Community-based participatory research with native American communities: the chronic disease self-management program. Health Promot Pract. 2010;11(6):888–99.

Howard BV, Roman MJ, Devereux RB, Fleg JL, Galloway JM, Henderson JA, Howard WJ, Lee ET, Mete M, Poolaw B, et al. Effect of lower targets for blood pressure and LDL cholesterol on atherosclerosis in diabetes: the SANDS randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;299(14):1678–89.

Russell M, Fleg JL, Galloway WJ, Henderson JA, Howard J, Lee ET, Poolaw B, Ratner RE, Roman MJ, Silverman A, et al. Examination of lower targets for low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and blood pressure in diabetes--the stop atherosclerosis in native diabetics study (SANDS). Am Heart J. 2006;152(5):867–75.

Karanja N, Lutz T, Ritenbaugh C, Maupome G, Jones J, Becker T, Aickin M. The TOTS community intervention to prevent overweight in American Indian toddlers beginning at birth: a feasibility and efficacy study. J Community Health. 2010;35(6):667–75.

Leslie JH. Uli'eo Koa program: incorporating a traditional Hawaiian dietary component. Pacific health dialog. 2001;8(2):401–6.

Witmer JM, Hensel MR, Holck PS, Ammerman AS, Will JC. Heart disease prevention for Alaska native women: a review of pilot study findings. J Women's Health. 2004;13(5):569–78.

DeWeese AD, Kmiecik NE, Chiriboga ED, Foran JA. Efficacy of risk-based, culturally sensitive Ogaa (walleye) consumption advice for Anishinaabe tribal members in the Great Lakes region. Risk Anal. 2009;29(5):729–42.

Driscoll D, Sorensen A, Deerhake M. A multidisciplinary approach to promoting healthy subsistence fish consumption in culturally distinct communities. Health Promot Pract. 2012;13(2):245–51.

Smith J, George VA, Easton PS. Home-grown television: a way to promote better nutrition in a native Alaskan community. J Nutr Educ. 2001;33(1):59–60.

Thompson JL, Allen P, Helitzer DL, Qualls C, Whyte AN, Wolfe VK, Herman CJ. Reducing diabetes risk in American Indian women. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(3):192–201.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Solange Majewska Saxby, Dustin Valdez, Melanie Wasurick, Kelly Sloan, and Christine Kajiwara for their assistance with preparation of the manuscript.

Funding

The project described was supported by grant, “Clinical and Translational Research Infrastructure Network IDeA Center,” grant number #5 U54 GM104944–05 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIGMS or NIH.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors conceived of the study. JB drafted the manuscript and both authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

JB is an Associate Professor in the Department of Human Nutrition, Food and Animal Sciences at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. She has an interest in obesity prevention and health promotion in diverse populations. Much of her current work centers on nutrition education and development of tools to evaluate nutrition education programs aimed at promoting healthy eating. Her previous work at the University of California, Davis involved the development of two tools, a food behavior checklist and physical activity questionnaire, to be used in the low-income Spanish-speaking community in the U.S. to evaluate nutrition education interventions.

AB is an Associate Professor at the Center for Alaska Native Health Research, Insitute of Arctic Biology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Her research interests are in the role of nutrition and physical activity in the development and prevention of chronic diseases, determinants of dietary and physical activity patterns, development and evaluation of theory-based interventions, and minority health, particularly in indigenous populations.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Banna, J., Bersamin, A. Community involvement in design, implementation and evaluation of nutrition interventions to reduce chronic diseases in indigenous populations in the U.S.: a systematic review. Int J Equity Health 17, 116 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0829-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0829-6