Abstract

Background

Nutrition interventions, often delivered at the household level, could increase their efficiency by channelling resources towards pregnant or lactating women, instead of leaving resources to be disproportionately allocated to traditionally favoured men. However, understanding of how to design targeted nutrition programs is limited by a lack of understanding of the factors affecting the intra-household allocation of food.

Methods

We systematically reviewed literature on the factors affecting the allocation of food to adults in South Asian households (in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Islamic Republic of Iran, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka) and developed a framework of food allocation determinants. Two reviewers independently searched and filtered results from PubMed, Web of Knowledge and Scopus databases by using pre-defined search terms and hand-searching the references from selected papers. Determinants were extracted, categorised into a framework, and narratively described. We used adapted Downs and Black and Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklists to assess the quality of evidence.

Results

Out of 6928 retrieved studies we found 60 relevant results. Recent, high quality evidence was limited and mainly from Bangladesh, India and Nepal. There were no results from Iran, Afghanistan, Maldives, or Bhutan. At the intra-household level, food allocation was determined by relative differences in household members’ income, bargaining power, food behaviours, social status, tastes and preferences, and interpersonal relationships. Household-level determinants included wealth, food security, occupation, land ownership, household size, religion / ethnicity / caste, education, and nutrition knowledge. In general, the highest inequity occurred in households experiencing severe or unexpected food insecurity, and also in better-off, high caste households, whereas poorer, low caste but not severely food insecure households were more equitable. Food allocation also varied regionally and seasonally.

Conclusion

Program benefits may be differentially distributed within households of different socioeconomic status, and targeting of nutrition programs might be improved by influencing determinants that are amenable to change, such as food security, women’s employment, or nutrition knowledge. Longitudinal studies in different settings could unravel causal effects. Conclusions are not generalizable to the whole South Asian region, and research is needed in many countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Every day, households must make difficult decisions about how limited food should be shared among their members. In low-income countries, around 793 million people are undernourished [1] and over 3.5 million mothers and children under five die every year because they are undernourished [2]. So, these food allocation decisions have important nutritional, and sometimes life-critical, consequences.

It is often assumed that food is allocated inequitably in households in the United Nations-defined region of South Asia (in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Islamic Republic of Iran, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka) [3]. Tangential evidence of significantly higher female than male infant mortality rates [4] and social and cultural gender discrimination that pervades numerous cultural and religious practices [5, 6] are suggestive of a plausible pathway by which discrimination against women leads to them not receiving their ‘fair share’ of food [7]. For instance, young women often stay at home and avoid moving around or interacting with the community (a practice known as purdah), women often describe their husband as their God, and it is common for women to serve men first and themselves last [8, 9].

International reviews have not found a consistent global trend of inequitable intra-household food allocation, except in South Asia [10,11,12]. In South Asia the scant evidence available suggests that women are discriminated against and receive less than their ‘fair share’, particularly in the allocation of high status, nutrient-rich foods [9, 13, 14]. This means that nutrition programs providing social transfers at the household level may fail to reach the intended target recipients, such as the most undernourished or pregnant women. On the other hand, if program implementers know which factors affect food allocation, and can identify those amenable to change, programs could be designed to target those individuals more effectively. Furthermore, behaviour change interventions without social transfers, or other programs or policies not directly related to nutrition, may be able to increase intra-household equity and improve nutritional outcomes by pushing the right levers.

However, intra-household food allocation has often been described as a ‘black box’ that is poorly understood [15, 16]. This may be because economic consumption and nutrition surveys are typically collected at the household rather than individual level, and also because evidence has been segregated by academic discipline. Thus, this study aims to identify the determinants of intra-household food allocation, focusing on allocation between adults from South Asian households, using a systematic and multidisciplinary literature review.

Materials and methods

We followed guidelines on systematic search protocols from Reeves et al. [17] and Petticrew and Roberts [18] and reporting guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [19]) when relevant.

Search method

In two phases between October 2015 and January 2017, two authors independently ran and filtered the searches in PubMed, Web of Science Core Collection, and Scopus databases. The former two databases were included because they contain multi-disciplinary peer-reviewed literature, and the latter database (Scopus) because it contains non peer-reviewed literature.

We used a combination of medical subject heading (MeSH) and free text search terms, using asterisks to indicate a wildcard operator. The search syntax used in PubMed was:

(((((family OR household*)) AND (food OR energy intake OR food habits OR diet OR nutrition*)) AND (allocat* OR distribut* OR decision* OR shared OR sharing OR share))) AND (age factors OR "age" OR sex OR "gender")

South Asia was not used as a search term because databases have different systems for cataloguing studies geographically, and because international or theoretical results were also included. Instead, studies from other regions were excluded in the filtering process. This increased the sensitivity of the search at the expense of specificity, giving more irrelevant (but also more relevant) results. Other search terms relating to ‘inequity’, and ‘determinants’ were also not included to ensure adequate sensitivity.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included quantitative, qualitative, anthropological, and theoretical studies from peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed sources that referred to the determinants of inequity in intra-household food allocation among adults. Inequity was defined as occurring when one person’s food needs were met more adequately than another’s needs [12]. ‘Food’ could refer to calories, nutrients, food quantities, food types, or dietary diversity, and ‘needs’ were defined as biological requirements. We also included any papers that described the determinants of inequitable food allocation without explicitly measuring food intakes or needs if the paper referred to relative food allocations within households, rather than effects on absolute intakes.

Recognising that the capability to control food distribution decisions might be as important for wellbeing outcomes as the resulting food allocation [20, 21], we considered including literature on the determinants of control over food selection, preparation, and serving. However, since this review is intended to inform nutrition programming, and to limit the scope, we focussed on food allocation outcomes only. Therefore, this review excluded the extensive and multidisciplinary body of work on intra-household influences on food purchasing and preparation decisions, unless they were shown to affect the distribution of food.

We included any studies explaining inequity between different adults (different age-sex groups or different pregnancy or lactating status). The cut-off for adults was ≥15 years because studies often include ‘women of reproductive age’ by using the age range of 15 to 49 years. We excluded papers that only referred to food allocation among children (or between adults and children), or did not report on food allocation directly, for example by referring to anthropometry or energy expenditure. We also excluded any papers that did not refer to any determinants other than age-sex group or pregnancy status.

We included all studies relating to the UN-defined region of South Asia: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Islamic Republic of Iran, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka. We also included theoretical and international references that were not specific to a particular research setting. There was no publication date cut-off, because we predicted that empirical and high quality evidence would be limited and so did not want to exclude dated but relevant literature.

The search results were exported into EndNote reference management software for filtering. Excluded papers were organised into different folders labelled according to their reason for exclusion. Disparities in inclusion / exclusion decisions were resolved by consultation with a third author. From the systematic search results, we searched through the reference lists to find additional relevant results. We added additional sources by communication with the authors.

Study quality assessment

To assess the quality of quantitative results we used a modified Downs and Black checklist [22], and for qualitative results we used the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist [23]. Given the breadth and heterogeneity of results expected, a meta-analysis was not possible and so sources of bias were not factored into the data synthesis.

Data extraction strategy

Two authors independently extracted the author name, publication year, study location, study method, and determinant(s) of food allocation into Microsoft Excel databases. We then mapped out each determinant on paper, by grouping them into different themes. The identified themes were discussed and disparities resolved by referring back to the text. These themes were compiled into a conceptual framework, with discussion from all authors.

Results

The result filtering process is shown in Fig. 1. Fifteen results were identified from the database search, 43 results were added by searching references, and two papers were added from communication with the authors, giving a total of 60 results.

The publication date, location, study and analysis method, sample size and characteristics, determinants, and food allocation outcome measures for the selected studies are summarised in Tables 1, 2 and 3. Of the 60 studies reviewed, around one quarter quantitatively estimated the associations between at least one determinant and food allocation, another quarter were qualitative studies, and the remaining half made theoretical, anecdotal, or speculative references to determinants. Nearly every quantitative study used a different outcome measure, whereas the qualitative, theoretical and anecdotal results tended not to define the outcome or discuss differences in nutritional requirements. Over half were from Bangladesh (n = 14) or India (n = 18), and around one third did not refer to any specific country or were international reviews. Publication dates ranged between 1972 and 2016, and 70% were published before 2000.

Quality assessment of selected papers

There was limited empirical evidence, a diverse range of methods used, heterogeneity in the outcome measure, a high proportion of anecdotal results, and limited methodological detail. This meant that it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis of any key determinants. Quality assessments for quantitative and qualitative results are given in Tables 4 and 5 respectively.

Quality assessments showed that the results were limited by the representativeness of the samples, and methods for quantifying and addressing non-response. Quantitative results rarely gave exact p-values (in many cases there was no statistical test) and few qualitative studies discussed the potential influence of the interviewer on the respondents’ answers, the rationale for their sampling methods, or their analysis techniques.

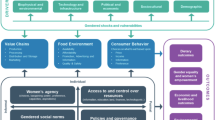

Framework of determinants of intra-household food allocation

Eighteen determinants emerged from the thematic analysis and are illustrated in a framework in Fig. 2. The framework also gives intuitive (rather than evidence-based) hierarchy and linkages between determinants. These linkages are not given at the intra-household level, where categorisation of a complex reality into boxes becomes particularly difficult as determinants overlap, complement or compete with one another.

The findings are narratively summarised by determinant, starting at the intra-household level, then the household level, and finally the distal determinants.

Intra-household level determinants

Relative economic contributions or physically strenuous work

Many theoretical or anecdotal studies suggested that selective investment in economically productive members (typically adult men) was a rational household survival strategy in the South Asian context of predominantly manual farming labour and economic returns to health [12, 24,25,26,27,28,29]. However, these gender differences were hypothesised to differ by wealth status, with poorer households being more reliant on women’s economic productivity (and so more equitable) than less poor households [4].

Three quantitative studies corroborated this food-health-income link, although none directly measured the effect of relative income on food allocation. Rathnayake and Weerahewa [30] found that mothers’ incomes were positively associated with their own relative calorie allocations, but the authors did not adjust for total household income. Using body size as a proxy for economic capacity, Cantor and Associates [31] found a positive association between body size and relative food allocation, although it is not known whether the authors adjusted for the higher energy requirements associated with heavier people. Pitt et al. [32] found that men’s health ‘endowments’ (pre-existing health status) determined their allocations of food, whereas women’s did not; a 10% increase in health endowment was associated with a 6.8% increase in calorie intake for men but only one tenth of that for women [32]. These differences were posited to reflect gender differences in economic returns to nutritional investment.

The food-health-income linkage was supported by qualitative studies that reported respondents’ beliefs that income earners deserved to be allocated more food [33, 34], but this was often conflated with beliefs about physiological requirements, particularly for manual labourers ([35] and Morrison J, Dulal S, Harris-Fry H, Basnet M, Sharma N, Shrestha B, Manandhar DS, Costello A, Osrin D, Saville N: Formative qualitative research to develop community-based interventions addressing low birth weight in the plains of Nepal. Working draft, in preparation). One study also reported beliefs that elderly people should be allocated favoured foods to acknowledge their ‘past contributions’ to the household [36], and that men required more than women because men’s work was more physically strenuous than women’s home-based work [36]. Conversely, Hartog [28] anecdotally suggested that the allocation of food according to economic contributions was no longer justified because of the increased mechanisation of agricultural work, and Aurino [37] supported this empirically. There was no association between gender differences in workload (with 15-year old girls working significantly more than 15-year old boys) or frequency of exercise and the gender differences in dietary diversity.

Cultural and religious beliefs about food properties and eating behaviours

Sixteen studies described cultural beliefs about food properties and eating behaviours as a determinant of food allocation, typically showing how these beliefs caused women to receive comparatively less.

Some foods were believed to be ‘unhealthy’, ‘strengthening’ or ‘digestible’, and therefore deliberately avoided or selected by vulnerable people, such as elderly people, or pregnant or lactating women [28]. Short-term ‘transitory’ states, such as menstruation and illness that are perceived to make a person ritually unclean (‘jutho’ (Nepalese)), were reported to cause inequity in food allocation [9, 38]. Certain fruits and vegetables were considered unhealthy for post-partum or lactating women [9], and other foods were believed to cause illness [39] or skin allergies [40] in the breastfeeding child. Elderly people were believed to require soft ‘digestible’ [9] and ‘strengthening’ foods [39, 41]. Pregnant women were reported to require ghee (clarified butter), to facilitate an easier, lubricated birth [33], but avoid certain foods that cause illness, indigestion, fits, delirium, or large babies (and therefore difficult labour) [39] and eat less because of a belief that a full stomach would harm the baby (Morrison J, Dulal S, Harris-Fry H, Basnet M, Sharma N, Shrestha B, Manandhar DS, Costello A, Osrin D, Saville N: Formative qualitative research to develop community-based interventions addressing low birth weight in the plains of Nepal. Working draft, in preparation). Another phase condition is puberty; according to the ‘pubertal hypothesis’ households might change intra-household food allocation in favour of adolescents going through pubertal growth spurts, however this was not supported empirically [37].

The categorisation of foods as heating, neutral or cooling was also linked to differential food allocation [9]. Examples of ‘heating’ foods included wheat, fish, millet, and milk, and ‘cooling’ foods included yogurt, fruits, green beans, gourds, and rice [41]. Again, these categories were related to the condition of the individual; for instance, lactating women avoided cooling foods [41]. Some authors noted that these restrictions caused an overall reduction in women’s dietary intake [41] perhaps due to insufficient household budget for nutritious alternatives [39]. The overlap of women being in the ‘phase condition’ of being pregnant, having low social status, and extreme poverty, was hypothesised as a cause of inequitable allocation of food towards pregnant women [29], whereas another study found that food insecure households did not adhere to food proscriptions due to a lack of food [40].

Cultural beliefs about the status or value of foods were also linked to food allocation [42]. Some people were allocated or ‘channelled’ specific foods, and these foods were often high status and expensive. For example, ghee (a high status food) was often only given to men [9] (perhaps with the exception of pregnant women, as documented earlier). Food ‘channelling’ was associated with significantly higher food quantities, so those who were given special foods were also given more food in total [9].

Religious beliefs may affect the distribution of food. For example, beliefs about the meaning of food, such as the act of eating being considered a form of worship in Islam, was suggested as a determinant of food allocation, although the direction of effects was not specified [43]. Fasting caused women to be allocated comparatively less food, because women fasted more frequently and strictly than men [27, 33].

Eating order was another key factor in food eating and allocation behaviours. Daughters-in-law, often young, newly married women, tended to serve themselves last (to show deference and ensure the wellbeing of male members [44]) and this was associated with eating less [9, 33, 40] and also lower quality diets than others [34, 45]. Gittelsohn [9] found that late serving order at meal times, being the food server, and not having a second helping were all significantly negatively associated with the quantity of food consumed. Two authors suggested that the negative effects of serving order were caused by limited food availability, because women tended to ensure everyone else had enough before serving themselves the remainder [9, 44].

Relative social status within the household, according to cultural norms

High social status and perceived deservedness of household members was reported by 14 studies as a determinant of intra-household food allocation, although no studies quantified the effect empirically. Some mentioned status in general terms, without ascribing high or low status to particular household members but suggesting that people with lower status would receive less food and less preferred foods [12, 14, 28, 29, 46], whereas others reported that men had higher status and therefore were allocated more food [9, 41, 47]. Pelto [46] noted that modernisation and increasing urbanisation was reducing the effect of status on food allocation.

Women’s identity as being lower status, frugal, modest, and subservient was described as a determinant of food allocation that favoured men but was often internalised by women [33, 48]. This identity was also interlinked with perceptions of body image, that also led women to eat comparatively less [48].

In addition to differences between genders, food allocation was also determined by differences in social rankings among women within households [47], hierarchy within the patriline [34], and variations within individuals over time. Women received more food as their status increased with age [9], by having children [41], and, particularly, by having sons [49]. In contrast, Rizvi [50] anecdotally suggested that increases in female status over time did not affect food allocation.

Belief that everyone should be given their ‘fair share’

Overlapping these beliefs about food properties and status were locally-held beliefs about fairness, and different definitions of what ‘fair’ means [48]. An Indian study concluded that beliefs about fairness affected food allocation because the respondents were reluctant to discuss disparities in food allocation [51]. Abdullah [36] also indicated this, by reporting a respondent’s description of a mother-in-law as a “bad woman” (p112) if she did not give her daughter-in-law special foods that others received, and Madjdian and Bras reported that Buddhist households allocated food according to appetite [40]. Pitt et al. reported that the tendency for households to equalise food allocation, rather than allocate food in an income-maximising way, was a reflection of households’ aversions to inequity [32]. Pinstrup-Andersen also hypothesised that perceived nutritional need determined food allocation (arguably a definition of fairness) [15]. Conversely, three others reported an ideological belief that men deserved to be given more than women [33, 43, 52].

Decision-making, social mobility, and control over resources

The ten studies on decision-making, control over resources, social mobility, or identity of the cook were all anecdotal or theoretical. Few specified who the decision-maker was or who would benefit from the decisions [15, 26, 53]. Haddad et al. noted that female decision-makers may be more likely than male decision-makers to allocate food in a way that maximised the household’s nutritional outcomes [11], and other work suggested that women’s control over income [25, 54, 55] (or production or purchasing [52]) would affect food allocation in favour of women. However, decision-making in nuclear households was also a risk factor for inequitable allocation towards women, as female decision-makers were responsible for ensuring that everyone else was sufficiently fed [55].

Related to this was different household members’ social mobility, and freedom to go food shopping or access food outside of the home [29, 53]. Women were described as having less social mobility and this was linked to lower food allocations [53]. However, it was also suggested that there may be less inequity against women than expected because food allocation occurs within the household, which, compared with the public sphere, is a domain in which women traditionally have more control [14].

Bargaining power

Related to this, many studies suggested that ‘bargaining power’ was an important determinant of food allocation. Some described a general linkage [55], while others described various microeconomic theories whereby individuals rationally aim to maximise their utility by bargaining over household resources such as food [12, 24, 56]. The strength of a person’s bargaining power is determined by their ‘fallback position’ (the utility that the individual would achieve if cooperation with other household members fails). Bargaining power may be predicted by the size of dowry for women [55], social norms that determine how goods such as food can be exchanged or used, and /or perceived requirements [56]. Naved also indicated that bargaining power might affect food allocation, with specific reference to micronutrients [35]. Appadurai described the process of bargaining with food, particularly in reference to daughters-in-law feeling resentment about their subservient role [8]. Daughters-in-law were reported to communicate resentment by being reluctant to cook, destroying food, or making small signs of discontent when serving food [8].

Food as a means to establish and reinforce interpersonal relationships

A study on the psychology of feeding found that food serving may be determined by the emotional state of the server and recipient, and that feeding was done to build relationships [57]. Serving and eating food was reported as a key determinant of intra-household food allocation [34] and a means to indicate rank [8], show disrespect or displeasure ([58] and Morrison J, Dulal S, Harris-Fry H, Basnet M, Sharma N, Shrestha B, Manandhar DS, Costello A, Osrin D, Saville N: Formative qualitative research to develop community-based interventions addressing low birth weight in the plains of Nepal. Working draft, in preparation), punish or reward people [29], or express love and strengthen relationships [28]. Two studies suggested that a strong bond between husband and wife might reduce the inequity against the wife that would otherwise be imposed by the mother-in-law ([51] and Morrison J, Dulal S, Harris-Fry H, Basnet M, Sharma N, Shrestha B, Manandhar DS, Costello A, Osrin D, Saville N: Formative qualitative research to develop community-based interventions addressing low birth weight in the plains of Nepal. Working draft, in preparation).

Individual tastes and preferences

One study [15] reported a general hypothesis that food preferences determine allocations. One study found that women were allocated the less-preferred foods [35], and another found that women prioritised their own food preferences the least [59]. A new vegetable production program, which had increased the availability of less popular vegetables, had caused an increase in women’s consumption of those vegetables [35].

Household-level determinants

Food insecurity and scarcity

Evidence on the effect of household food security was mixed. Seven studies provided a hypothetical link between food insecurity and food allocation [11, 25, 42, 52,53,54, 60].

Most studies suggested that women were more sensitive to changes in food availability, and acted as a buffer for the household in food insecure conditions [40, 52, 55], particularly the youngest daughter-in-law [34]. Household calorie adequacy was a better predictor of calorie adequacy for women than for men [61], years of higher rice yields were linked to higher equity in calorie allocation [62], and women were more sensitive to food price changes (had higher food price elasticity) than men [63]. Although one study found no overall effect of food insecurity, there were differential effects between villages, and in food-scarce months landowning households favoured men at the expense of women while labourer households favoured adults at the expense of children [27]. Another study found some ethnic variability in these effects, with Indo-Nepalese household using discrimination against women as a coping mechanism during food shortages and Tibeto-Burmese households not changing their food distribution patterns in this way [64].

In contrast, some studies found opposing or no effects. Naved found that increased food availability did not affect food allocation patterns, but food scarcity led to men being less likely to have sufficient food than women [35]. Abdullah also found women’s proportion of men’s intakes increased from 81 to 90% between food secure and food short seasons, in poor households [36]. A later analysis by the same authors found no significant effect after adjusting for differential requirements [65], and another also found no effect of scarcity on calorie allocation [66].

Household wealth and income

Evidence was mixed on the effect of household wealth and income. Three quantitative studies reported no effect [31, 38, 67], while Pinstrup-Andersen’s [15] theoretical study hypothesised that there was an effect without specifying the direction. Two qualitative studies reported higher inequity in poorer households [33, 68], but a qualitative study reported that the source of food, whether bought or grown, had little effect on food decisions (Morrison J, Dulal S, Harris-Fry H, Basnet M, Sharma N, Shrestha B, Manandhar DS, Costello A, Osrin D, Saville N: Formative qualitative research to develop community-based interventions addressing low birth weight in the plains of Nepal. Working draft, in preparation).

Educational levels

Households with more educated household heads allocated less meat to women than men [69], whereas another two studies on female education showed no association with food allocation [30, 37].

Nutrition knowledge

Although studies linked food beliefs and food allocation, no studies measured the association between dietary knowledge and food allocation. Das Gupta suggested that lack of knowledge did not explain the comparatively inadequate intakes of pregnant and breastfeeding women in India [49], whereas others suggested the opposite [14, 38].

Household occupation

One study found that the greatest gender inequity occurred in agricultural labourer households, compared with market-based, subsistence farmers or non-agricultural households [62]. Another found that farm work and household chores were associated with consuming fewer snacks, and that all three (farm work, household chores, and snacks in a combined score) were significantly higher for women than men [45]. In contrast, two studies found no effect of being an agricultural labourer household [69] or household occupation [67] on food allocation. However, if the household head was a farmer, then milk was allocated more equitably and meat less so [69].

Land ownership

Only Bouis and Novenario-Reese mentioned the effect of land ownership, finding that landowning households were less equitable with their allocation of eggs but more equitable with fish [69].

Household size and structure

The effect of household size was also mixed. Van Esterik suggested that the number of senior women in a household would affect food allocation patterns [29], while Rizvi suggested that household size affected intakes of individuals, but not allocation patterns [68]. Rathnayake and Weerahewa reported a significant positive effect of household size on mothers’ relative calorie allocations in Sri Lanka [30], and a study from Pakistan also found higher intakes for the household head, pregnant women, and children under five years, relative to average household intakes, in larger households [38]. Conversely, another study showed that large household size (more than eight children) was associated with significantly higher male than female calorie adequacy [70].

(Morrison J, Dulal S, Harris-Fry H, Basnet M, Sharma N, Shrestha B, Manandhar DS, Costello A, Osrin D, Saville N: Formative qualitative research to develop community-based interventions addressing low birth weight in the plains of Nepal. Working draft, in preparation) reported a trend for food-related rules to be relaxed when women returned to their parental homes, where they had fewer food restrictions. This was supported by Abdullah [36], who found that women were given less or fewer special foods in the marital home, and so women (or adolescent, unmarried girls) received special treatment when at their parental homes. Comparing joint and nuclear households, Ramachandran reported that women were allocated comparatively less in nuclear households, where the women had the responsibility of feeding everyone; whereas, in joint households women were given more because their mother-in-law adopted the role of food planning and distribution [55].

Religion, ethnicity and caste

Evidence on the effects of religion, ethnicity and caste was limited and mixed. Van Esterik [29] hypothesised that religion was a determinant of food allocation, particularly through religious influence on food classifications systems. There were no differences between Buddhists and Christians in food allocation [67], but Buddhist families were more equitable than Hindu households [40]. Rathnayake and Weerahewa found no effect of ethnicity on relative calorie allocations [30], whereas Panter-Brick and Eggerman found that food shortages caused discrimination against women during food shortages among Indo-Nepalese households but not among Tibeto-Burmese households [64]. No studies explicitly described the effect of caste, but two studies implied that inequity would be greater in high caste groups [63, 71].

Distal determinants

Seasonality

Two quantitative studies relating to seasonality found contradictory, non-significant and unexplained effects on intra-household food allocation. In Bangladesh, Tetens et al. found more equity in food allocation during peak agricultural production seasons [72], whereas in India Chakrabarty found less equity in cereal consumption in the peak season [73]. A qualitative study from India found that women ate the least during planting and harvest seasons when they were working the hardest (and working harder than men) due to a lack of appetite from the exhaustion [74], and a seasonal calendar from Bangladesh showed that women were allocated fewer eggs and fish than men, particularly during food insecure months [75]. An anecdotal study suggested that predictable seasonal variation was unlikely to affect food allocation patterns because households would have coping strategies for predictable variations in food availability [29]. However, if this shortage overlapped with periods of more pregnancies or more female agricultural labour inputs, then women would have less adequate diets than other household members [29].

Village and region

Regional differences in intra-household food allocation were varied. Basu et al. found no differences between urban and rural areas among the Lechpas ethnic group in India [67], whereas a study from Pakistan found small but significant regional variation in micronutrient allocation [38], with higher dietary adequacy for men in certain regions and lower adequacy for pregnant or lactating women in others. The authors suggested that this may have been a result of regional differences in cultural attitudes and beliefs regarding pregnancy, but did not describe these attitudes in detail. Harriss-White also found differences in inequity between four different villages in India, which she hypothesised may have been due to differences in land ownership and methods of agricultural production [27].

Discussion

Although we searched for literature across South Asia, studies were mostly from Bangladesh, India, and Nepal, with few from Islamic Republic of Iran, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, and none from Afghanistan, Maldives or Bhutan. We identified eighteen determinants of intra-household food allocation, many of which were specific to the South Asian context and centred on interlinked aspects of poverty, cultural beliefs, and power. The review suggests that the most equitable households are low caste households [63] in which women earn an income [30] and there is low educational status of the household head [69] (indicative of lower socioeconomic status) but that equitable households will also be food secure [61] (indicative of higher socioeconomic status).

We hypothesise that these seemingly conflicting effects could be reconciled in a non-linear relationship between socioeconomic status and inequity. During acute or unexpected food shortages, households selectively invest limited calories in men because they have more labour opportunities [62, 63]. For example, recent unexpected shocks may include the 2015 Nepalese earthquakes [76]. As food security increases and food shortages become more predictable, households become more equitable [65, 72, 73]. Low caste households are often described as more egalitarian [71], partly because low caste men do not inherit land, [5] but also because women have comparatively higher economic contributions [73]. The positive effect of individuals’ relative economic contributions on their shares of household food is also supported by evidence from the Philippines [77] and China [78]. At higher levels of socioeconomic status, inequity may increase again [27]. This is supported by the finding that women from landowning Indian households are thinner than in landless households [45]. Inequity amongst higher socioeconomic groups may be characterised by preferential “channelling” of high status, often micronutrient-rich luxury foods such as meat or dairy [9], rather than by unequal allocation of staples that may occur in the poorest groups [62]. If true, this channelling could result in social rather than nutritional inequity, or perhaps inequity of micronutrients rather than calorie allocation. This may explain the surprising negative gradient in the prevalence of anaemia in women with increasing wealth in Nepal (anaemia: 32% in the lowest wealth quintile, and 49% in the middle quintile) [79], despite the relatively high cost of micronutrients required to reduce anaemia. This inequity may decline in households where women are highly educated and ‘modern’, as they may have the most knowledge of dietary requirements (to counteract discriminatory cultural food practices) and these households may be less socially conservative and restrictive towards women. Although no studies have provided evidence to support this directly, the prevalence of anaemia in Nepal does fall to 36% in the highest wealth quintile [79].

Any socioeconomic level, dynamic intra-household factors (such as bargaining, preferences and interpersonal relationships) will introduce variance within these trends, while cultural norms and food practices (that have wide local variation but are slow to change [40]) may introduce variance and also determine the strength of association between socioeconomic status on food allocation.

Limitations of the study, and future work

This study benefitted from a systematic literature search but the results and conclusions are limited by the lack of recent evidence. Given the rapid changes in labour migration, engagement in non-farm work, and mechanisation of farm work [80], the full framework should be tested with recent data. Another limitation is that most studies came from Bangladesh, India and Nepal, so the results may be less or not valid for other South Asian countries that did not have any or many studies (particularly Afghanistan, Bhutan, Maldives, Iran, and Pakistan). Even within the results from India, Bangladesh and Nepal, there is wide heterogeneity in culture, beliefs, and institutions, making generalisations difficult. Many results arose from snowballing, indicating poor indexing of multi-disciplinary evidence, so the included studies may be subject to citation bias.

Most papers considered only a few determinants in their analyses and did not control for possible confounders, so the pathways in the framework cannot be disentangled. For example, we cannot tell whether papers that tested the effects of seasonality or wealth on food allocation would have found the same results after controlling for household food security. Similarly, the overlap of cultural norms, social status, income earning, bargaining power, and participation in decision-making, means that the effects of these intra-household determinants cannot be distinguished. We expect that these intra-household determinants co-exist, sometimes reinforcing and other times opposing each other.

To truly understand these intra-household processes, longitudinal mixed methods are required to examine each possible determinant at different stages in the household life cycle (adolescents, newlyweds, senior members, elderly), with different phase conditions (during puberty, illness, menstruation, pregnancy, post-partum, and breastfeeding), at different points in the food acquisition–preparation–distribution pathway, in different socioeconomic groups, in different regions and in different seasons. Given the breadth of this evidence gap, research to inform nutrition program design could particularly focus on the determinants of food allocation that may be amenable to change, such as food security, women’s employment, or nutrition knowledge. Most studies focused on energy or food quantity, so more research is needed on the allocation of micronutrient-rich foods [27]. Other next steps could link the evidence on factors affecting the determinants in this framework, such as predictors of food choice, bargaining power, and food security.

Implications of the findings: what does this mean for nutrition interventions?

The findings indicate that women are disadvantaged in the allocation of food, and that women’s nutrition outcomes could be improved through changes in intra-household food allocation patterns. In particular, pregnant women tend to receive lower relative allocations, and this has important nutritional implications because nutrition during pregnancy is associated with maternal health outcomes, intra-uterine growth retardation, child health outcomes, and is a key point in the intergenerational cycle of undernutrition [81]. As such, interventions may need to particularly prioritise pregnant women.

By predicting the distribution of transfers at all levels of socioeconomic status, social transfer programs could be designed to ensure that the intended recipients receive the transfers. For example, programs delivering transfers in emergency contexts may need to ensure that transfers are large enough [82], so that transfers will reach less economically productive household members. Poorer households might require additional resources such as food or cash transfers to improve the nutritional status of women. Low caste households may be more likely to share these transfers equitably, and so additional intervention components (such as behaviour change communication) to ensure the transfers reach target recipients may only be required if the programmer intends to disproportionately target women (or pregnant women).

In contrast, transfers to high caste or better-off groups may need to include a behaviour change component to ensure that transfers reach women. Alternatively, programs delivering transfers to high caste groups could provide lower status, less desirable goods, such as flour rather than rice [83], to ensure that transfers will be preferentially distributed to lower status household members. This leads to a wider discussion on programmatic objectives, and whether programs intend to challenge patriarchal norms to empower women and improve nutrition, or to work within patriarchy to achieve optimal nutritional outcomes. Furthermore, high caste better-off households that can already afford more micronutrient-rich foods may not need more resources to improve maternal nutrition – behaviour change interventions may be sufficient.

Alternative, or complementary, approaches to improve intra-household equity in food allocation may include: interventions that provide income-generating activities for women, women’s groups to increase social mobility and bargaining power or otherwise empower women, or agricultural programs to improve food security.

Conclusions

There are many possible household-level and intra-household determinants of intra-household food allocation, but evidence is out-dated and not comprehensive. Local context and variation in social hierarchies makes generalised conclusions difficult. Programs delivering social transfers may find differential intra-household distribution of transfers in different socioeconomic groups. Programs affecting determinants that are amenable to change, such as household food security, bargaining power, and gender-specific labour opportunities, may cause changes in intra-household food allocation patterns.

References

FAO/ IFAD/ WFP. The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2015. Meeting the 2015 international hunger targets: taking stock of uneven progress. Rome: FAO; 2015.

Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, De Onis M, Ezzati M, Mathers C, Rivera J. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet. 2008;371:243–60.

Sen AK. Family and food: sex bias in poverty. In: Bardhan P, Srinivasan T, editors. Rural poverty in South Asia. New York: Columbia University Press; 1988. p. 453–72.

Chen LC, Huq E, d’Souza S. Sex bias in the family allocation of food and health care in rural Bangladesh. Popul Dev Rev. 1981;7:55–70.

Cameron MM. On the edge of the auspicious: Gender and caste in Nepal. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press; 1998.

Kondos V. On the Ethos of Hindu Women: Issues, Taboos, and Forms of Expression. Kathmandu: Mandala Publications; 2004.

Sen A, Sengupta S. Malnutrition of rural children and the sex bias. Econ Polit Wkly. 1983;18:855–64.

Appadurai A. Gastropolitics in Hindu South Asia. Am Ethnol. 1981;8:494–511.

Gittelsohn J. Opening the box: intrahousehold food allocation in rural Nepal. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33:1141–54.

Berti PR. Intrahousehold distribution of food: a review of the literature and discussion of the implications for food fortification programs. Food Nutri Bull. 2012;33:S163–70.

Haddad L, Peña C, Nishida C, Quisumbing A, Slack A. Food security and nutrition implications of intrahousehold bias: A review of literature. In: FCND Discussion Paper No 19. Washington, D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI); 1996.

Wheeler EF. Intra-household food and nutrient allocation. Nutr Res Rev. 1991;4:69–81.

Sudo N, Sekiyama M, Maharjan M, Ohtsuka R. Gender differences in dietary intake among adults of Hindu communities in lowland Nepal: assessment of portion sizes and food consumption frequencies. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60:469–77.

DeRose LF, Das M, Millman SR. Does female disadvantage mean lower access to food? Popul Dev Rev. 2000;26:517–47.

Pinstrup-Andersen P. Estimating the nutritional impact of food policies: a note on the analytical approach. Food Nutr Bull. 1983;5:16–21.

Behrman JR. Chapter 3. Peeking into the Black Box of Economic Models of the Household. In: Rogers BL, Schlossman NP, editors. Intra-Household Resource Allocation: Issues and Methods for Development Policy and Planning. Tokyo: United Nations University Press; 1990. p. 44–50.

Reeves BC, Deeks JJ, Higgins JP. Chapter 13. Including non-randomized studies. In: Higgins JP, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, vol. 1. Chichester: Wiley; 2008. p. 389–432.

Petticrew M, Roberts H. Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide. Cornwall: Blackwell Publishing; 2008.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–9.

Sen A. Well-being, agency and freedom: the Dewey lectures 1984. J Philos. 1985;82:169–221.

Sen A. Development as freedom. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press; 1999.

Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:377–84.

CASP Qualitative Checklist: CASP Checklists (URL: http://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/dded87_25658615020e427da194a325e7773d42.pdf; Accessed 01 Dec 2015). In Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). Oxford: CASP; 2014.

Doss CR. Testing among models of intrahousehold resource allocation. World Dev. 1996;24:1597–609.

Haddad L, Kanbur R. How serious is the neglect of intra-household inequality? Econ J. 1990;100:866–81.

Kumar S. A framework for tracing policy effects on intra-household food distribution. Food Nutr Bull. 1983;5:13–6.

Harriss-White B. Chaper 10. The Intrafamily Distribution of Hunger in South Asia. In: Dreze J, Sen A, editors. The Political Economy of Hunger: Volume 1: Entitlement and Well-being. Oxford: Clarendon; 1991.

Hartog AP. Unequal distribution of food within the household (a somewhat neglected aspect of food behavior). Nutrition Newsletter. 1972;10:8–17.

Van Esterik P. Intra-family food distribution: its relevance for maternal and child nutrition. In: Latham M, editor. Determinants of young child feeding and their implications for nutritional surveillance; Cornell International Nutrition Monograph Series No 14). New York: Cornell University; 1985. p. 73–149.

Rathnayake I, Weerahewa J. An assessment of intra-household allocation of food: a case study of the urban poor in Kandy. Sri Lankan J Agric Econ. 2002;4:95–105.

Cantor SM, Associates: Tamil Nadu Nutrition Study, 8 volumes. Haverford, Pennsylvania, USA.; 1973.

Pitt MM, Rosenzweig MR, Hassan MNH. Productivity, Health and Inequality in the Intrahousehold Distribution of Food in Low-Income Countries. Am Econ Rev. 1990;80:1139–56.

Khan M, Anker R, Ghosh Dastidar S, Bairathi S: Inequalities between men and women in nutrition and family welfare services: an in-depth enquiry in an Indian village. Population and Labour Policies Programme, Working Paper No 158, World Employment Programme Research, UNFPA Project No INT/83/P34, Geneva 1987.

Palriwala R. Economics and Partiliny: Consumption and Authority within the Household. Soc Sci. 1993;21:47–73.

Naved RT. Intrahousehold impact of the transfer of modern agricultural technology: A gender perspective. Washington, D.C: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI); 2000.

Abdullah M. Dimensions of intra-household food and nutrient allocation: a study of a Bangladeshi village. PhD Thesis. London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (University of London), 1983.

Aurino E. Do boys eat better than girls in India? Longitudinal evidence on dietary diversity and food consumption disparities among children and adolescents. Econ Human Biol 2016; 25:99-111.

Government of Pakistan: Micro-nutrient survey of Pakistan (1976-1977). vol. Volume II. Islamabad, Pakistan: Planning and Development Division; 1979.

Katona-Apte J. The socio-cultural aspects of food avoidance in a low-income population in Tamilnad, South India. J Trop Pediatr. 1977;23:83–90.

Madjdian DS, Bras HAJ. Family, Gender, and Women’s Nutritional Status: A Comparison Between Two Himalayan Communities in Nepal. Econ History Developing Regions. 2016;31:198–223.

Gittelsohn J, Thapa M, Landman LT. Cultural factors, caloric intake and micronutrient sufficiency in rural Nepali households. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:1739–49.

Gittelsohn J, Mookherji S, Pelto G. Operationalizing household food security in rural Nepal. Food Nutr Bull. 1998;19:210–22.

Den Hartog: Food habits and consumption in developing countries. Manual for field studies.. Wageningen Academic, Wageningen; 2006.

Kabeer N. Subordination and struggle: Women in Bangladesh. New Left Rev. 1988;168:95–121.

Barker M, Chorghade G, Crozier S, Leary S, Fall C. Gender differences in body mass index in rural India are determined by socio-economic factors and lifestyle. J Nutr. 2006;136:3062–8.

Pelto G: Intrahousehold Food Distribution Patterns. In Malnutrition, Determinants and Consequences: Proceedings of the Western Hemisphere Nutrition Congress VII held in Miami Beach, Florida, August 7-11, 1983 (White P ed. pp. 285 - 293. New York: Liss, A. R. Inc.; 1984:285 - 293.

Coffey D, Khera R, Spears D. Intergenerational effects of women’s status: Evidence from joint Indian families. 2015.

Messer E. Intra-household allocation of food and health care: Current findings and understandings—introduction. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:1675–84.

Das Gupta M. Life course perspectives on women's autonomy and health outcomes. Health Transition Review 1996;6:213-231.

Rizvi N. Life cycle, food behaviour and nutrition of women in Bangladesh. In: Huq J, editor. Women in Bangladesh: Some socioeconomic issues. Dhaka: Women for Women conference; 1981. p. 70–9.

Caldwell JC, Reddy P, Caldwell P. The social component of mortality decline: an investigation in South India employing alternative methodologies. Popul Stud. 1983;37:185–205.

De Schutter O. Gender equality and food security: Women’s empowerment as a tool against hunger. 2013.

Carloni A. Sex disparities in the distribution of food within rural households. Food Nutrition. 1981;7:3–13.

Haddad L. Women’s Status: Levels, Determinants, Consequences for Malnutrition, Interventions, and Policy. Asian Development Review. 1999;17:96–131.

Ramachandran N: Chapter 9. Women and Food Security in South Asia: Current Issues and Emerging Concerns. In; 2007: 219-240

Agarwal B. ”Bargaining” and Gender Relations: Within and Beyond the Household. Fem Econ. 1997;3:1–51.

Hamburg ME, Finkenauer C, Schuengel C. Food for love: the role of food offering in empathic emotion regulation. Front Psychol. 2014;5:1–9.

Miller BD. The endangered sex: neglect of female children in rural North India. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press; 1981.

Daivadanam M, Wahlström R, Ravindran T, Thankappan K, Ramanathan M. Conceptual model for dietary behaviour change at household level: a ‘best-fit’ qualitative study using primary dat. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:574.

Gunewardena: Chapter 28. Gender Dimensions of Food and Nutrition Security: Women’s Roles in Ensuring the Success of Food-based Approaches,. Improving Diets and Nutrition: Food-based approaches, Thompson, B and Amoroso, L (eds), Food and Agriculture Organisation 2014:328 - 334.

Kumar S, Bhattarai S: Effects of infrastructure development on intrahousehold caloric adequacy in Bangladesh. In Understanding how resources are allocated within households. pp. 21-22. IFPRI-World Bank, IFPRI Policy Briefs 8.; 1993:21-22.

Babu SC, Thirumaran S, Mohanam T. Agricultural productivity, seasonality and gender bias in rural nutrition: Empirical evidence from South India. Soc Sci Med. 1993;37:1313–9.

Behrman JR, Deolalikar AB. The intrahousehold demand for nutrients in rural south India: Individual estimates, fixed effects, and permanent income. J Hum Resour 1990;25:665-96.

Panter-Brick C, Eggerman M. Household responses to food shortages in western Nepal. Hum Organ. 1997;56:190–8.

Abdullah M, Wheeler EF. Seasonal variations, and the intra-household distribution of food in a Bangladeshi village. Am J Clin Nutr. 1985;41:1305–13.

Brahmam G, Sastry JG, Rao NP. Intra family distribution of dietary energy‐an Indian experience. Ecol Food Nutr. 1988;22:125–30.

Basu A, Roy SK, Mukhopadhyay B, Bharati P, Gupta R, Majumder PP: Sex bias in intrahousehold food distribution: roles of ethnicity and socioeconomic characteristics. Current Anthropol. 1986;27:536-39.

Rizvi N. Effects of policy on intra-household food distribution in Bangladesh. Food Nutr Bull. 1983;5:30–4.

Bouis HE, Novenario-Reese MJG. The determinants of demand for micronutrients, FCND Discussion Paper No. 32. In: FCND Discussion Papers. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI); 1997.

Chaudry R. Determinants of intra-familial distribution of food and nutrient intake in rural Bangladesh. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Draft Bangladesh Institute of Development Economics; 1983.

Rohner R, Chaki-Sircar M. Mothers and children in a Bengali village. Hanover, USA: University Press of New England; 1988.

Tetens I, Hels O, Khan NI, Thilsted SH, Hassan N. Rice-based diets in rural Bangladesh: how do different age and sex groups adapt to seasonal changes in energy intake? Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:406–13.

Chakrabarty M. Gender difference in cereal intake: possible impacts of social group affiliation and season. Anthropol Anz. 1996;54:355–60.

Nichols CE. Time Ni Hota Hai: time poverty and food security in the Kumaon hills, India. Gender Place Culture. 2016;23:1404–19.

Mukherjee N: Participatory learning and action: With 100 field methods. Concept Publishing Company, New Delhi; 2002.

Webb P, West Jr KP, O’Hara C. Stunting in earthquake-affected districts in Nepal. Lancet. 2015;386:430–1.

Senauer B, Garcia M, Jacinto E. Determinants of the intrahousehold allocation of food in the rural Philippines. Am J Agric Econ. 1988;70:170–80.

Luo W, Zhai F, Jin S, Ge K. Intrahousehold food distribution: a case study of eight provinces in China. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2001;10:S19–28.

DHS: Nepal Demographic and Health Survey Key Indicators Report. (Ministry of Health KNE, Kathmandu; The DHS Program, ICF, Maryland. ed. Ministry of Health, Nepal; 2017.

Rigg J. Land, farming, livelihoods, and poverty: rethinking the links in the rural South. World Dev. 2006;34:180–202.

Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Rizvi A, Gaffey MF, Walker N, Horton S, Webb P, Lartey A, Black RE, Group TLNIR. Evidence-based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: what can be done and at what cost? Lancet. 2013;382:452–77.

Gentilini U. Cash and food transfers: A primer. Occasional Papers No. 18. World Food Programme: Rome; 2007.

Ahmed AU, Quisumbing AR, Hoddinott JF, Nasreen M, Bryan E. Relative efficacy of food and cash transfers in improving food security and livelihoods of the ultra-poor in Bangladesh. Washington, D.C: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI); 2007.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was funded by Child Health Research Appeal Trust (CHRAT) and UKaid from Department for International Development South Asia Research Hub (PO 5675). The donors had no role in the design, analysis, interpretation, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

HHF designed the study protocol, with inputs from NMS and AC. HHF and NS conducted the literature search, and NMS resolved any conflicts in study selection. HHF drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Harris-Fry, H., Shrestha, N., Costello, A. et al. Determinants of intra-household food allocation between adults in South Asia – a systematic review. Int J Equity Health 16, 107 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0603-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0603-1