Abstract

Background

Women’s empowerment interventions represent a key opportunity to improve nutrition-related outcomes. Still, cross-contextual evidence on the factors that cause poorer nutrition outcomes for women and girls and how women’s empowerment can improve nutrition outcomes is scant. We rapidly synthesized the available evidence regarding the impacts of interventions that attempt to empower women and/or girls to access, participate in and take control of components of the food system.

Methodology

We considered outcomes related to food security; food affordability and availability; dietary quality and adequacy; anthropometrics; iron, zinc, vitamin A, and iodine status; and measures of wellbeing. We also sought to understand factors affecting implementation and sustainability, including equity. We conducted a rapid evidence assessment, based on the systematic literature search of key academic databases and gray literature sources from the regular maintenance of the living Food System and Nutrition Evidence Gap Map. We included impact evaluations and systematic reviews of impact evaluations that considered the women’s empowerment interventions in food systems and food security and nutrition outcomes. We conducted an additional search for supplementary, qualitative data related to included studies.

Conclusion

Overall, women’s empowerment interventions improve nutrition-related outcomes, with the largest effects on food security and food affordability and availability. Diet quality and adequacy, anthropometrics, effects were smaller, and we found no effects on wellbeing. Insights from the qualitative evidence suggest that women’s empowerment interventions best influenced nutritional outcomes when addressing characteristics of gender-transformative approaches, such as considering gender and social norms. Policy-makers should consider improving women’s social capital so they can better control and decide how to feed their families. Qualitative evidence suggests that multi-component interventions seem to be more sustainable than single-focus interventions, combining a livelihoods component with behavioral change communication. Researchers should consider issues with inconsistent data and reporting, particularly relating to seasonal changes, social norms, and time between rounds of data collection. Future studies on gender-transformative approaches should carefully consider contextual norms and avoid stereotyping women into pre-decided roles, which may perpetuate social norms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Most research on women within food systems focuses on their roles as caregivers and cooks [1]. However, women are key actors within food systems, serving as producers, processors, distributors, vendors, and consumers. Often living in more vulnerable conditions than men due to societal norms, women face negative, differential access to affordable, nutritious foods relative to men. Gendered food systems interact with gender equality and equity at individual and systemic (community) levels, as well as in formal (traditions and economic roles) and informal (household norms) ways, also referred to as the four quadrants of change (Fig. 1). To achieve food systems transformation, women will need to have adequate agency and control over resources. Social norms, policies, and governance structures must be fair and equitable to allow women access to food and livelihood opportunities. However, many food systems and nutrition interventions are criticized as disempowering because they can entrench stereotypes by targeting women and girls explicitly in the roles of caregivers or cooks.

Theory of change, from Njuki et al. [2]

Improvements in women’s empowerment are expected to facilitate women’s interactions with the food system and improve the nutrition of women and their communities directly and indirectly. Women can improve their own and their children’s nutritional status when they have the socio-economic power and social capital to make decisions on food and non-food expenditures and the ability to take care of themselves and their families [3]. By giving women more control and self-determination, women’s empowerment interventions are expected to have larger impacts than similar interventions that do not incorporate an empowerment approach. Women’s empowerment interventions may allow women to make the choices that are most likely to benefit them while addressing the broader social and cultural context. As a result, women’s empowerment interventions represent a key opportunity to improve nutrition-related outcomes, and women’s empowerment has been highlighted as a critical, crosscutting theme for food systems transformation [4]. However, cross-contextual evidence on the factors that cause poorer nutrition outcomes for women and how women’s empowerment can improve nutritional outcomes is still scant [2].

Gender-transformative approaches (GTA) acknowledge the equal role that all genders have in women’s empowerment and thus target men as agents of change to transform structural barriers and social norms [5]. While many women’s empowerment interventions include GTA approaches, women’s empowerment and GTA differ mainly in the following aspects (adapted from [6]):

-

Approaches to women’s empowerment often focus only on women. GTA, on the other hand, aim to address broader social contexts and avoid essential zing men and women.

-

A central element of GTA is intersectionality, i.e., considering the interconnections between different social identities, such as gender, race, ethnicity, or geographic location.

For our purposes, women’s empowerment interventions within the food system are defined as “efforts targeted at increasing women's abilities to make decisions regarding the purchase and consumption of healthy foods” based on 3ie’s Food Systems and Nutrition Evidence Gap Map [1]. Moore et al. [1] determined that, as of January 2022, there were 21 evaluations of the impacts of interventions that target women’s abilities to make decision regarding the purchase of healthy foods, for example by improving decision-making on household expenditures. However, these studies had not been synthesized to determine average treatment effects and key contextual factors driving to impact. In this rapid evidence assessment, we focus on 10 of those studies which looked at specific outcomes related to food security, food affordability and availability, diet quality and adequacy, anthropometrics, iron, zinc, vitamin A, iodine status, and measures of well-being.

This rapid evidence assessment provides a novel synthesis of the available evidence on the impacts of interventions to support women’s empowerment within the food system, contributing to the literature base on both women’s empowerment and food systems. It is expected to support policymakers, experts, and stakeholders in making evidence-informed decisions regarding the implementation and design of such interventions. Stakeholders can use this work to understand how to better integrate gender-transformative approaches as one characteristic of feminist development policies, to improve nutritional outcomes in the project and study design process while acknowledging and moving past the use of stereotypes.

In this rapid assessment, we run a meta-analysis and a barriers and facilitators analysis of interventions on the economic and social empowerment of women with the goal of providing them the means and ability to affect dietary decisions; [7, 8]. As a result, we focus on food environment and dietary measures, a subset of the factors presented in Fig. 1. Measures of wellbeing are also considered due to their direct link with women’s empowerment. The interventions we identified primarily relate to behavior change communication, skills training, and asset transfers. Interventions were often complex and integrated other components, such as microcredits, self-help groups, and provision of vitamins supplements. They often targeted men as well as women, making them gender-transformative.

Objectives and research questions

The objective of this work was to rapidly synthesize the available evidence regarding the impacts of interventions that attempt to empower women and/or girls to access, participate in and take control of components of the food system. Outcomes considered are limited to measures of the food environment and diet. This fills the synthesis gap identified by Moore et al. [1]. We also sought to understand factors affecting implementation and sustainability, including equity. We specified the following research questions a priori (Appendix 1):

-

1.

What are the effects of women’s empowerment interventions within the food system on food availability, accessibility, and affordability, of healthy diets or nutritional status?

-

2.

Are there any unintended consequences of such interventions?

-

3.

Do effects vary by context, approach to empowerment, or other moderators?

Methodology

To respond to these research questions, we conducted a rapid evidence assessment (REA). As far as possible this REA is based on the rigorous methodologies adopted in a systematic review [9]. However, due to time and resource limitations, the search and screening process and the data extraction process were shortened [10]. These abbreviated steps allowed for the rapid nature of this rapid evidence assessment. The protocol for the REA was developed a priori in February 2021 and is provided in Appendix 1.

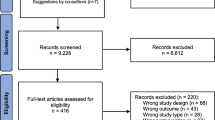

Search and screening based on the EGM by Moore et al. [1]

We did not conduct a new search for impact evaluations, but relied on an existing, open-source evidence gap map (EGM) by Moore et al. [1]. The EGM includes all impact evaluations and systematic reviews of impact evaluations of interventions within the food system which measure outcomes related to food security and nutrition in low- and middle-income countries (Appendix 7). Because the search conducted by Moore et al. [1] was not specifically focused on women’s empowerment, rather it included women’s empowerment among a variety of other topics, it is possible that some articles may have been missed. However, there is no reason to believe that there would have been any systematic bias in the types of articles that were omitted or that this would have meaningfully affected results.

-

The search by Moore et al. [1] was extensive and systematic, covering 12 academic databases and 13 gray literature sources (Appendix 7). Single screening with safety first was used at both title and abstract and full text stages. A machine learning classifier was applied to automatically exclude studies with a low probability of inclusion. Although the original search was complete in May 2020, the search is continuously updated with studies added to the EGM through January 2022 considered for this REA. As of January 2022, over 160,000 articles were screened for inclusion in the EGM and 2,647 studies were included Appendix 7.

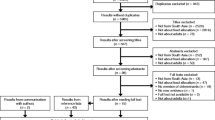

Because this REA is based on the search by Moore et al. [1], the same criteria for eligible populations, comparators, and study designs employed by Moore et al. [1] were used for this REA. Moore et al. [1] included interventions which targeted women’s empowerment within food systems. Women’s empowerment interventions which functioned outside the food system, such as those related to economic empowerment outside of the food system, were not included. From the 21 studies on women’s empowerment interventions included in their EGM, we selected the ten studies evaluating outcomes related to the food environment (food security and food affordability and availability), diet (diet quality and adequacy, anthropometrics, and micronutrient status), or well-being. Table 1 presents the population, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study designs (PICOS), modified from Moore et al. [1], employed by this REA.

Although we did not perform any new searches for impact evaluations for this rapid evidence assessment, we conducted a targeted search in Google Scholar looking for the qualitative papers related to included studies to allow us to investigate how impacts were achieved. The search included the name of the program or intervention, if available, as well as the country the intervention took place in. Eligible qualitative study designs were [11]:

-

A qualitative study collecting primary data using mixed methods or quantitative methods of data collection and analysis and reporting some information on all the following: the research question, procedures for collecting data, procedures for analyzing data, and information on sampling and recruitment, including at least two sample characteristics.

-

A descriptive quantitative study collecting primary data using quantitative methods of data collection and descriptive quantitative analysis and reporting some information on all the following: the research question, procedures for collecting data, procedures for analyzing data, and information on sampling and recruitment, including at least two sample characteristics.

-

A process evaluation assessing whether an intervention is being implemented as intended and what is felt to be working well and why. Process evaluations may include the collection of qualitative and quantitative data from different stakeholders to cover subjective issues, such as perceptions of intervention success or more objective issues, such as how an intervention was operationalized. They might also be used to collect organizational information.

While the identification of qualitative evidence was limited to studies linked to the included impact evaluations, the process of data extraction, critical appraisal, and evidence synthesis was independent.

Data extraction

Data extraction templates were modified from 3ie’s standard coding protocol for systematic reviews, reflecting another shortened step for the purposes of making this assessment rapid (Appendix 2). The primary modification to the tool was a restriction on the number and type of outcomes considered. The outcomes considered were broad and could be measured using a variety of indicators. To restrict the number of outcomes extracted, we specified preferred and secondary indicators of interest a priori (Table 2). This limited the analysis to be conducted to only the specified outcomes. Composite measures were always preferred over disaggregated ones. If multiple analyses were presented considering the same outcome (ex. Univariate analysis and a regression with control variables), the data from the model preferred by the author was extracted. If no preferred model was specified, the model with the most control variables was used.

Two team members extracted bibliographic, geographic information, methods, and substantive data. Substantive data were related to interventions, selected outcomes, population (including gender/age disaggregation, when available), and effect sizes. Discrepancies were reconciled through a discussion between the two team members. Qualitative information on barriers and facilitators to implementation, sustainability and equity implications, and other considerations for practitioners was extracted by a single reviewer.

Included quantitative impact evaluations were appraised by two independent team members using a critical appraisal tool (Appendix 3). Qualitative studies linked to included impact evaluations were critically appraised by a single reviewer using a mixed methods appraisal tool developed by CASP [12] and applied in Snilstveit et al. [11] (Appendix 3).

Synthesis approach

We provide a narrative summary of the papers identified. This includes an overall description of the literature and a general synthesis of findings. Key information from each study, such as intervention type, study design, country, outcomes, measurement type, effect sizes, and confidence rating is summarized in tables. Results from meta-analyses and associated forest plots are presented in the section on the findings. Qualitative information is summarized in a section on implications for implementation and sustainability.

Meta-analysis

In addition to presenting individual effect estimates for all six outcomes, we conducted five meta-analyses to provide summary effect estimates on the five outcomes for which we had sufficient data. This meta-analysis provides additional value relative to presenting the individual effect estimates by presenting a summary effect estimate. Meta-analyzed effects have the benefit of being supported by a broader (Figs. 2 and 3), potentially more generalizable evidence base than individual point estimates. Previous works have statistically synthesized similar evidence, for instance, on food security and food affordability and availability [13, 14], anthropometrics measures [14,15,, 16, 17] micronutrients status [18–20], diet quality and adequacy [21, 22],

Because only ten studies were included, meta-analysis was conducted at the outcome (column 1, Table 2), not the indicator level (column 2, Table 2). However, due to variations in the indicators used and their interpretation, we also present the standardized effect estimates for each study in each forest plot (Figs. 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) and Appendix 6. The decision to conduct meta-analysis was made on a case-by-case basis after considering if the indicators adequately captured the same underlying concept [23]. We also summarize the findings of each study, including narratively reporting on individual effects, in Table 3. For all outcomes except micronutrient status, the metrics were determined to be sufficiently similar to warrant a joint analysis in addition to the presentation of individual effects.

To compare the effect sizes, we converted all of them to a single metric, Cohen's d. We then converted all Cohen's d to Hedges g to correct for small sample sizes. We chose the appropriate formulae for effect size calculations in reference to, and dependent upon, the data provided in included studies. For example, for studies reporting means (X) and pooled standard deviation (SD) for treatment (T) and control or comparison (C) at follow-up only, we used the following formula:

If the study did not report the pooled standard deviation, it is possible to calculate it using the following formula:

where the intervention was expected to change the standard deviation of the outcome variable, we used the standard deviation of the control group only:For studies reporting means (X) and standard deviations (SD) for treatment and control or comparison groups at baseline (p) and follow-up (p + 1):

\(d = \frac{{\Delta \underline{X}_{p + 1} - \Delta \underline{X}_{p} }}{{SD_{p + 1} }}\) For studies reporting mean differences (∆X) between treatment and control and standard deviation (SD) at follow-up (p + 1):

\(d = \frac{{\Delta \underline{X}_{p + 1} }}{{SD_{p + 1} }} = \frac{{\Delta \underline{X}_{Tp + 1} - \Delta \underline{X}_{Cp + 1} }}{{SD_{p + 1} }}\) For studies reporting mean differences between treatment and control, standard error (SE) and sample size (n):

For studies reporting regression results, we followed the approach suggested by Keef and Roberts (2004) using the regression coefficient and the pooled standard deviation of the outcome. Where the pooled standard deviation of the outcome was not unavailable, we used the regression coefficients and standard errors or t-statistics to do the following, where sample size information is available in each group:

where n denotes the sample size of treatment group and control. We used the following where total sample size information (N) is available only (as suggested in Polanin [34]):

When necessary, we calculated the t statistic (t) by dividing the coefficient by the standard error. If the authors only report confidence intervals and no standard error, we calculated the standard error from the confidence intervals using the following:

If the study did not report the standard error, but did report t, we extracted and used this as reported by the authors. If an exact p value was reported but no standard error or t, we used the following Excel function to determine the t-value.

where outcomes were reported in proportions of individuals, we calculated the Cox-transformed log odds ratio effect size [35]:

where OR is the odds ratio calculated from the two-by-two frequency table.

We fitted a random effects meta-analyses model when we identified two or more studies that we assessed to be sufficiently similar. We assessed heterogeneity using the DerSimonian–Laird estimator by calculating the Q statistic, I2, and τ2 to provide an estimate of the amount of variability in the distribution of the true effect sizes [23]. We were unable to explore heterogeneity using moderator analyses due to the small number of included studies.

Qualitative synthesis

The meta-analysis conducted with the quantitative data has been complemented by a thematic synthesis utilizing the extracted qualitative data. Qualitative data were synthesized thematically by a single team member and reviewed by two other team members. Themes considered related to non-nutrition impacts, barriers and facilitators to impact, and cost evidence.

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

We included ten studies retrieved through the systematic search done for the Food Systems and Nutrition Evidence Gap Map, conducted in January 2022 (Table 3). An additional, low-quality systematic review was identified and excluded from analysis. Four of the ten included studies were implemented in Bangladesh, while the remaining studies where in Burkina Faso, Ghana, India, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, and Uganda. The four studies in Bangladesh represent unique evaluations of a cash transfer program, an agricultural training program, and two fully independent evaluations of Targeting-Ultra-Poor program (TUP) with a time gap of eight years and somewhat different intervention designs. More information on study characteristics can be found in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Randomized controlled trials (n = 4) and difference-in-difference were the most common designs (n = 4). Half of the studies using difference-in-difference also used statistical matching (n = 2). One study used statistical matching alone and one used regression discontinuity to identify counterfactuals. Nine additional qualitative papers associated with seven interventions were also identified and included.

Almost all studies provided training (n = 8). Some also provided asset transfers (n = 6) and behavior change communication (n = 3; Tables 3, 6 in Appendix 6, and Additional file 1: Table S1). Behavior change communication interventions generally communicated messages about women’s empowerment and women’s roles within their communities. Often, they targeted men, making them gender-transformative. Training and educational interventions focused on agriculture and/or nutrition, but some also considered entrepreneurship and water, sanitation, and hygiene. Asset transfers were largely related to cash or agricultural inputs, including livestock.

Food affordability and availability outcomes were the most common (n = 5). Diet quality and adequacy and food security outcomes were also common (n = 4 each). Anthropometric measures, micronutrient status, and well-being outcomes were less common (n = 2 each).

We found nine qualitative reports related to seven interventions. Additional qualitative information was not found for the remaining interventions. The qualitative components of the main studies and additional studies were minimal and primarily focused on contextual information from the researchers. Many of the qualitative studies used focus group discussions or key informant interviews to better understand participants’ lived realities. Qualitative data contextualized results of empowerment interventions and food and nutrition security based on the differing intervention locations and intersecting social, cultural and gender norms that influence the impacts on nutrition and other key outcomes.

All the randomized controlled trials except Blakstad et al. [26] have an overall rating of ‘some concerns’, mainly due to reporting bias, performance bias, and selection bias (Fig. 7; Appendix 5). Deininger and Liu [28] also encountered issues related to deviation from the intended interventions and the unit of analysis did not correspond to the unit of randomization.

Two quasi-experimental studies were rated as having a low risk of bias (Fig. 8; [32, 33]), one study as having ‘some concerns’ [29], and one as having a high risk of bias [27]. The major sources of bias were related to reporting bias, spill-over, cross-over and contamination, performance bias, and confounding.

What are the effects of women’s empowerment interventions on food environment, diet, and well-being outcomes?

Standardized effects are reported in Table 7 in Appendix 6, calculated as outlined in the Methodology section. The meta-analysis results of the random effects model are reported in Table 4. We could not run a meta-analysis on micronutrient status because the two studies looking at it measured different underlying concepts which could not be meaningfully combined.

Effect of women’s empowerment interventions on food security outcomes is promising

Our analysis of the effects of women’s empowerment interventions suggests they improved food security outcomes overall (\(\widehat{\mu }=0.24\) [95% CI: \(0.001\) to \(0.47\)], \(p=0.048\), Fig. 4). Women receiving these interventions had a 59.5% chance of having food security scores above the mean in the control group. There was significant variation in the size of the effect, ranging from 0.07 in Tanzania, to 0.67 in Bangladesh.

We included four studies which reported the following indicators: food security index (whether the household had surplus food or deficit, enough food to eat, and could afford to eat two meals a day), household food insecurity assessment scale (HFIAS), skipped meals, and food available to meet a household’s needs of two meals a day [25, 26, 29, 33]. All studies provided training or education, mostly related to agriculture. Three also provided some form of asset transfer [25, 29, 33].

Two studies were assessed as having some concerns related to risk of bias [25, 29] and two were assessed as low risk of bias [26, 33].

Effect of women’s empowerment interventions on food affordability and availability outcomes is promising

Our analysis of the effects of women’s empowerment interventions suggests they improved the availability and affordability of food (\(\widehat{\mu }=0.23\) [95% CI: \(0.09\) to \(0.38]\) \(p<0.01,\) Fig. 5). Women receiving these interventions had a 59.1% chance of having food affordability and availability scores above the mean in the control group. There was significant variation in the size of the effect, ranging from 0.08 in Uganda, to 0.49 in Bangladesh.

Food affordability and availability was measured in five included studies, per capita food consumption, food consumption per capita (Rs/year), total food consumption expenditure (food production and market purchases in the 12 months preceding the survey), and grain stock (kg) [24, 26,27,, 2829, 33]. We included two estimates for Ahmed et al. as the results were reported for independent samples from the North and South of Bangladesh, without an overall estimate for all the areas.

All studies but Deininger and Liu [28] included assets transfer, such as cash, cash crops [24, 27], or livestock, seeds, or vitamin A supplements [29, 33]. All studies, except Ahmed et al. [24] included trainings or education on nutrition [27], or agriculture [29, 33], or enterprise/accountability [28]. Two studies also included a behavior change communication component [24, 27].

Ahmed and colleagues also reported increases in monthly food consumption per capita in both northern and southern regions of their intervention area (North areas: g = 0.32 [95% CI: 0.27 to 0.38]; South areas: g = 0.22 [95% CI: 0.16 to 0.27]) and per capita daily intake caloric (North areas: g = 0.22 [95% CI: 0.17 to 0.28]; South areas: g = 0.09 [95% CI: 0.043 to 0.15]). Three other intervention arms (provision of food, cash, or food plus cash) were also evaluated. However, we were not able to include them in the meta-analysis as they were not comparable to the other studies. All three reported similar impacts.

Only Bonuedi et al. were assessed as having a high risk of bias, the remaining studies have either some concerns [24, 28, 29] or low risk of bias [33].

Effect of women’s empowerment interventions on diet quality and adequacy outcomes is promising

Our analysis of the effects of women’s empowerment interventions suggests they improved diet quality and adequacy (\(\widehat{\mu }=0.09\) [95% CI: \(0.06\) to \(0.12]\), \(p<0.01,\) Fig. 6). Women receiving these interventions had a 53.6% chance of having diet quality and adequacy scores above the mean in the control group. The variations among the range of effects were not as high as for other outcomes, ranging from 0.08 in India to 0.14 in Sierra Leone.

Four studies reported impacts related to diet quality and adequacy, such as dietary diversity and amount of food or protein consumed [27, 28, 30, 33]. All four studies employed training/education interventions focused on agriculture [27, 30, 33] or enterprise/accountability [28]. Two studies also transferred assets [27, 33], and one included a behavioral change communication component [27].

One study was scored as low risk of bias [33], two were scored as having some concerns [28, 30], and one was rated as high risk of bias [27].

Effect of women’s empowerment interventions on anthropometrics is promising but there is a lack of evidence

Our analysis of the effects of women’s empowerment interventions suggests they improved measures of weight relative to height (\(\widehat{\mu }=0.12 [\) 95% CI: \(0.002 \mathrm{to} 0.23]\), \(p=0.046\) Fig. 7). Children of women receiving these interventions had a 54.8% chance of having anthropometrics scores above the mean in the control group.

Two studies reported impacts on anthropometric measures of children based on WHO z-scores [31, 32]. Both studies transferred agricultural [32] or financial assets [32]. The Heckert and colleagues’ study also included a behavioral change communication strategy, while Marquis and colleagues included entrepreneurship training. Marquis et al. [32] also report a decrease in weigh-for-age (g = − 0.42 [95% CI: − 0.77 to − 0.06]) and an increase in height-for-age (g = 0.40 [95% CI: 0.04 to 0.75]). Heckert and colleagues were scored as having some concerns about bias while Marquis et al. [32] had low risk of bias.

Effect of women’s empowerment interventions on micronutrient status is promising but there is a lack of evidence

Two studies considered the effects of women’s empowerment interventions on micronutrient status, but these could not be meaningfully combined in a meta-analysis because they measured different underlying concepts. Haque et al. found that Suchana's gender-transformative approach, which encompassed a portfolio of agriculture and entrepreneurship trainings, increased the consumption of iron, folic acid tablets (g = 0.25 [95% CI:0.21 to 0.28]). Heckert et al. evaluated an agricultural education and behavior change communication strategy, but they found no effect on hemoglobin levels (g = − 0.10 [95% CI: − 0.03 to 0.23]). Both studies were rated as having some concerns about bias.

Effects of women’s empowerment interventions on mental well-being outcomes is not significant and there is a lack of evidence

Our analysis of the effects of women’s empowerment interventions shows no effect on mental health outcomes (\(\widehat{\mu }=0.08 [\) 95% CI: \(0.01 \mathrm{to} 0.14], p=0.088\), Fig. 8). Bandiera et al. [25] reported a mental health index constructed based on self-reported happiness and mental anxiety, while Pan et al. [33] measured the level of worries regarding insufficient food. Both studies evaluated assets transfer interventions, such as livestock, seeds, vegetables growing, and specific trainings which accompanied to the transfers. Pan et al. [33] paper was assessed as having a low risk of bias, while Bandiera et al. [25] paper was assessed as having some concerns related to performance bias.

Implications

Implications for non-nutrition outcomes

Authors of many of these studies concluded that the interventions accomplished their goals of supporting women’s empowerment, often by introducing gender-transformative approaches which challenged traditional social norms. The Enhanced Homestead Food Production (E-HFP) program in Burkina Faso included a gender-transformative approach in which it improved men’s perceptions of women as farm managers and increased respect and communication in agri-business activities [31]. The accompanying behavior change communication intervention allowed mothers to better communicate with men to improve familial support and adopt positive nutrition behaviors, such as improved feeding practices. Similarly, the Suchana program in Bangladesh resulted in improvements in women’s empowerment and maternal healthcare practices using a gender-transformative approach [30]. Women became more confident to discuss issues around food and management of household resources with their partners [27]. Self-help group participation improved social awareness and leadership skills. Women mobilized to protest child marriage and violence against women in their communities [37]. The Targeting-Ultra-Poor program (TUP) in Bangladesh increased saving and borrowing opportunities for women. These interventions allowed women to accumulate savings and spend more judiciously, rather than consistently responding to immediate needs.

Two interventions which combined training with improved accessibility of agricultural assets increased opportunities for paid work. The agricultural intervention in Uganda resulted in an increase in work for wages and freed up off-farm work times for the entire household, including women [33]. Similarly, because of the TUP program, the labor market choices of household members aside from the targeted woman also shifted [25]. However, women themselves did not have increased labor participation. Women in the program spent most of their time at home and were generally not employed outside of the home [38]. In fact, women reported that they preferred to stay at home due to low pay and social stigma in workplaces.

Similarly, two interventions focusing on household farming for improved nutritional outcomes were labor and time intensive, which resulted in high attrition [26]. This additional labor was an increased burden on women and took away from their time to acquire and prepare food for their families [27]. When data collection coincided with harvest months in Sierra Leone, women’s involvement in the farming activities increased their time constraints and adversely affected caregiving practices.

Barriers and facilitators

Restrictive social norms preventing women from being able to take advantage of the interventions as intended was a common barrier. Structural gender barriers act as a driver of inequality in the household and community, as specified in Njuki et al. theory of change (Fig. 1). In highly patriarchal societies, such as Sierra Leone, deeply entrenched social and cultural norms marginalize women, restrict their decision-making and exclude them from accessing or controlling household resources [27]. Single-focus interventions that only targeted nutrition or value chain inputs without behavior change communication related to social norms were not able to fully realize potential impacts because entrenched norms were significant barriers to long-lasting change [33]. Even if women were given the tools to work outside the home or own assets, they were often blocked from leveraging these tools by norms that dictate how women can act and work [33]. Gender-transformative approaches address this social barrier by including men to ensure that the full impacts of interventions can be leveraged and realized as intended.

In the TUP program, asset transfers that were intended for women members of households were controlled by men due to social norms [39]. Social norms delineated what type of assets women were allowed to own. Larger livestock, like cattle, were automatically perceived to belong to men because they were higher in value and traded more often. Their sale required an adult male’s consent, which restricted women’s ability to own and manage them. Restrictions almost always came from jealous or violent husbands. When the TUP transferred small livestock such as poultry, that women more often owned, it was easily controlled by women [39]. Religious norms also played a role in restricting women’s public movements. Care responsibilities were reinforced by conservative social norms for women in Bangladesh, where women were demarcated as primary caregivers in the home [37].

In some contexts, community and men’s support also facilitated improvements in outcomes, demonstrating the importance of gender-transformative approaches that actively challenge gender norms and power inequities between genders. In the Homestead Food Production intervention in Tanzania, women who lived near neighbors who also grew crops at home had higher dietary diversity [26]. Participants who were close to markets were able to access, trade and procure food and related items easier than those who were farther away [25]. If husbands and other men in the household or community were more receptive to change, then progress was more visible with women in the TUP [37]. If a husband was more open to his wife engaging in out-of-house activities, livelihood strategies were more successful.

Multi-component interventions may leverage synergistic effects to have greater impacts than the individual components would have [27]. Complementary program arms can reinforce each other in achieving desired results and reduce implementation costs to achieve the same objectives [27]. The asset-based component of the PROACT program in Sierra Leone had little effect. However, when combined with a behavior change communication component, it increased women’s decision-making power, shifting women’s roles in the household, and expanding women’s ability to work outside the house. Behavior change communication components of the TMRI program in Bangladesh combined with the incentive of asset transfers allowed women’s sustained participation and achieved an overall improvement in household indicators over the course of the program [38].

Interventions which do not address equity can be less successful and re-enforced social norms. Often, entrenched norms and roles were not acknowledged within included interventions [40]. Failure to address these norms may have resulted in some interventions being unsuccessful. This was seen in the Bangladesh asset transfer program which did not address norms around livestock ownership and resulted in men gaining control over some of the transferred assets [39]. Interventions which took place at the home and approached women as caregivers and providers may have further perpetuated the stereotype of women within these roles [37].

Unfortunately, the long time needed to change social norms was a barrier to these interventions achieving impact in the short period in which they were evaluated. The theory of change from women’s empowerment interventions to improved nutrition outcomes assumes a change in social norms, which requires a significant amount of time (Fig. 1). Change within the food system is a dynamic process which often depends on other changes outside the scope of these interventions. Moreover, change processes are not straightforward and can be accompanied by setbacks, sometimes occurring parallel to positive effects. Behavior change communication can be slow to expand women’s empowerment and households’ social status and networks [24]. Impacts often become apparent in the long-term when foundational improvements consolidate and are dependent on internal and external factors. Food and nutrition security and women’s empowerment may need to be achieved in stages, according to different resources and opportunities [33]. For example, in India, the District Poverty Initiative fostered group formation and supported more mature groups, which could have significant economic benefits in the long term [28]. Because the study utilized data from three and six years after group formation, the research implies there may have been impacts on capital endowments and economic effects on individuals and the group itself. Authors of evaluations that occurred within 12 months of the interventions’ end indicated that a more comprehensive understanding of women’s empowerment and nutritional outcomes would require longer-term and more frequent data collection [26, 31].

Specific characteristics of the target group can affect impacts and may explain heterogeneity in results. Household decisions regarding assets and nutrition were shaped by local ecological and economic conditions [24]. In India, target groups that were the poorest saw the largest asset accumulation and empowerment improvements. This resulted in the poorest benefitting both socially and economically [28]. Interventions which leverage existing groups may experience high attrition if the groups themselves experience attrition. For example, the Enhancing Child Nutrition through Animal Source Food Management program targeted microcredit groups, and experienced significant attrition among those who were not benefiting from the loan program [32]. This may not have been observed if the intervention targeted women directly and did not work through the microcredit group.

Cost information

Cost reporting was low (n = 3). When studies reported cost data, either through cost per participant or cost benefit analysis, the benefits generally outweighed the costs. The District Poverty Initiative in India found that net present value of benefits from the project were approximately $1,690 million, significantly more than the project cost of $110 million. Even if benefits only lasted for one year the estimated benefits still significantly exceed project costs, with a benefit–cost ratio of 1.5 to 1 [28]. The TUP program in Bangladesh also showed that average benefits, including increased household welfare, were 3.21 times larger than costs. Big push programs, like the TUP, required large investment. However, in this case, it resulted in cost-effective and sustainable change in household welfare, including nutrition [37].

Multi-component interventions can be cost-effective because they combine complementary initiatives, such as interventions targeting nutrition and social norms. This was seen in PROACT where impacts were only achieved once a behavior change component was added to the asset transfer [27]. Similarly, when added to an asset transfer program, the TMRI women’s empowerment behavior change communication component costs $50 per beneficiary per year, which is a relatively low cost compared to stand-alone behavior change communication interventions [24]. Low-cost additional activities can have greater impact than expected, especially when integrated with other components. The training of model farmers in Uganda improved cultivation methods at relatively low cost when compared with the cost of inputs, such as a high-yield and drought-resistant seeds. Both training and the provision of inputs improved women’s efficiency in household gardens [33]. However, when calculating costs, the additional cost of such labor should not be ignored, especially because these costs are often born by the women that these interventions are trying to help [26].

Discussion

Overall, our analyses suggest women’s empowerment interventions can improve measures of the food environment and diet. We find significant and positive effects on food security (0.24 [95%CI: 0.00 to 0.47], n = 4), food affordability and availability (\(\widehat{\mu }=0.023\)[95% CI: \(0.06\) to \(0.38]\), n = 6), and diet quality and adequacy (\(\widehat{\mu }=0.09\) [95% CI: \(0.06\) to \(0.12\)], n = 4). With two studies considering outcomes related to weight-for-length (\(\widehat{\mu }=0.12\) [95% CI: \(0.00\) to \(0.23\)]) and wellbeing (\(\widehat{\mu }=0.08\) [95% CI: \(0.01\) to \(0.15\)]) each, the evidence is too limited to draw conclusions. Although impacts on diet quality and adequacy, anthropometrics, and well-being were positive, they were smaller than impacts on more proximate outcomes, such as food security and food affordability and availability. Impacts seem to reduce along the causal chain. Some of the more final outcomes, such as anthropometric and well-being measures, can take years to meaningfully change. As such, modest early effects may imply longer-term change.

Insights from the qualitative evidence suggest that women’s empowerment interventions best influenced food environment and diet outcomes when gender and social norms were considered. However, often, entrenched norms and roles were not acknowledged in these interventions [40]. When community, and especially male support, was found, it may have facilitated impact. Including gender-transformative approaches in women’s empowerment interventions may be essential to challenge and overcome existing social norms which often prevent the achievement of intended impacts. Such transformative approaches may be necessary to allow women to fully benefit from ongoing interventions. Restrictive social norms may prevent women from taking full advantage of the interventions and reduce potential impacts.

Although women’s empowerment interventions are promising approaches for improving measures of the food environment and diet, interventions may need to move beyond women’s empowerment interventions include GTA and gain the buy-in of men and the community. This can result in increased power of women in household decision-making while also sensitizing men to women’s pursuits of work outside of the home [41]. GTA require cultural and social adaptation to local contexts through strengthened local partnerships and capacities while considering intersectionality, e.g., by considering different interconnections between gender, socioeconomic class, and caste divisions. GTA and intersectionality, both characteristics of feminist development policy, are crucial to progress on gender equality and leverage the full potential of policies and interventions. Similarly, interventions should attempt to improve women’s social capital so they can better control and decide how to acquire and prepare food for their families [39]. Focusing on the duration of interventions is also important. Long-term interventions may be needed to account for slow processes, such as changing social norms. Multi-component interventions, which combine a livelihoods component (asset transfer or financial services) with behavioral change communication and advocacy, may be more effective than interventions focusing on just livelihoods or behavioral change.

With ten included studies, the evidence base is small, which can reduce generalizability. Variation in the measures considered in the meta-analysis may drive heterogeneity in results. However, the overall quality of the evidence is fair with most of the studies (n = 6) rated as having ‘some concerns’ regarding bias. Three studies were assessed as having ‘low risk of bias.’ Given the low number of studies available and potential biases, the results should be interpreted with some caution.

Although the evidence was generally of high quality, we had some concerns related to reporting, performance, and selection bias of the randomized controlled trials. Within the quasi-experimental studies, we found issues related to reporting bias, spill-over, cross-over and contamination, performance bias, and confounding. Some authors reported issues with incomplete or low-quality data, for instance, incomplete children’s health or vaccination records. Moreover, some children aged out during the evaluation period making the data inconsistent. Other studies did not collect data across seasons, an essential element when collecting data on agriculture outcomes, which can act differently across seasons. Short interventions and short data collection periods might also prevent impacts from being identified. These limitations could result in findings being somewhat unreliable.

Strengths, limitations & future directions

The interventions considered in this analysis were multi-faceted, often considering two or three components: behavior change communication, training, and asset transfers. As such, it is not possible to determine which of these approaches is most effective. Future work can isolate the effects of these different pathways, as done by Bonuedi et al. [27], to determine which of these components is most effective.

The meta-analyses presented here combine disparate indicators of broad concepts. The combined analysis of these different indicators is justified because they measure the same underlying concept. However, the variation in indicator used by each study may explain the heterogeneity in results. For example, the analysis on food security combines a food security index, household food insecurity assessment scale, number skipped meals, and indicator of whether food is available to meet a household’s needs of two meals a day. The framing of food attributes as positive versus negative can affect attitudes toward food [42], so framing questions around food security and insecurity may produce different results. As such, indiviudal effect estimates should also be considered and are reported within each forest plot and in Appendix 6. Summaries of the effects identified by each study are provided in Table 3. Future work should move toward standardizing measurement to allow for better comparability. Some of such efforts already exist, but should be further supported to allow for stronger synthesis [43, 44].

Given the limited evidence base, more research is needed in this field broadly. All the studies were implemented in Sub-Saharan Africa or South Asia, leaving evidence gaps in Central America, South America, and Central Asia. Most studies were implemented in contexts that were particularly patriarchal and restrictive for women, meaning that results in more egalitarian societies may be different. Although we were able to run a five meta-analysis, interpretation of the results is limited due to the low number of studies and variation in the indicators synthesized. Cost data will also be needed to determine if these impacts are cost-effective. To determine the sustainability of impacts over time, future studies should have longer intervention periods to ensure accurate capture of perceived impacts. Qualitative data can add rich depth to quantitative findings by adding context, experiences and meaning to the lived experiences of project participants. Mixed-methods studies should focus on identifying impacts and then using qualitative research to interrogate how these impacts were achieved. Studies in places with caste divisions, such as India or Bangladesh, could have benefited from a disaggregation in the experiences and outcomes of women and households from different castes. Future studies should try to avoid outcome measurement bias, reporting bias, spill-over, cross-over and contamination, performance bias, confounding, and selection bias. Future studies should also ensure that data collection is representative of different seasons and contextual changes, to avoid incomplete or insufficient data [26, 30, 32].

Due to the rapid nature of this work, results should be interpreted with caution. The studies included in this review are those found through the systematic search for the EGM produced by Moore et al. [1] as of January 2022. It is possible that a more sensitive and targeted search strategy would identify additional studies. Moreover, the REA is limited in the scope of interventions included. Only those which take place within the food system are considered; interventions functioning outside of the food system may influence nutrition outcomes but have not been considered.

Availability of data and materials

All the data used to support finding in this study derive from the included study, please see the full list in the Reference section.

References

Moore N, Lane C, Storhaug I, Franich A, Rolker H, et al. The effects of food systems interventions on food security and nutrition outcomes in low- and middle-income countries. International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie); 2021.

Njuki J, Eissler S, Malapit H, Meinzen-Dick R, Bryan E, Quisumbing A. A review of evidence on gender equality, women’s empowerment, and food systems: Food Systems Summit Brief Prepared by Research Partners of the Scientific Group for the Food Systems Summit. 2021. https://bonndoc.ulb.uni-bonn.de/xmlui/bitstream/handle/20.500.11811/9132/fss_briefs_review_evidence_gender_equality.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

WHO. Understanding the women’s empowerment pathway. Brief #4. Improving nutrition through agriculture technical brief series. Arlington: USAID/Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) Project. 2014.

United Nations Food Systems Summit. Chapter 2 key inputs from summit workstreams action tracks. 2021. https://foodsystems.community/food-systems-summit-compendium/action-tracks/. Accessed 27 Jan 2022.

Cole SM, Kantor P, Sarapura S, Rajaratnam S. Gender-transformative approaches to address inequalities in food, nutrition and economic outcomes in aquatic agricultural systems. 2015.

Wong, F, Vos A, Pyburn R, Newton J. Implementing gender transformative approaches in agriculture. A Discussion Paper for the European Commission. 2019.

Cheung J, Gursel D, Kirchner MJ, Scheyer V. Practicing feminist foreign policy in the everyday: a toolkit. Germany; 2021.

Thompson L. Defining feminist foreign policy. Washington: International Center for Research on Women; 2019. p. 1–7.

Campbell Collaboration. (2017). Campbell systematic reviews: Policies and guidelines.

Barends, E., Rousseau, D. M. & Briner, R. B. CEBMa Guideline for Rapid Evidence Assessments in Management and Organizations. Amsterdam. 2017. https://www.cebma.org/wp-content/uploads/CEBMa-REA-Guideline.pdf

Snilstveit B. Systematic reviews: from ‘bare bones’ reviews to policy relevance. J Dev Effect. 2012;4(3):388–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439342.2012.709875.

CASP (2018). Qualitative Checklist. [online] Available at: https://casp-uk.net/images/checklist/documents/CASP-Qualitative-Studies-Checklist/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf Accessed: 1st March 2022.

Korth M, Stewart R, Langer L, Madinga N, Rebelo Da Silva N, Zaranyika H, van Rooyen C, de Wet T. What are the impacts of urban agriculture programs on food security in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Environ Evid. 2014;3(1):1–10.

Stewart R, Langer L, Da Silva NR, Muchiri E, Zaranyika H, Erasmus Y, Randall N, Rafferty S, Korth M, Madinga N, de Wet T. The effects of training, innovation and new technology on African smallholder farmers’ economic outcomes and food security: a systematic review. Campbell Syst Rev. 2015;11(1):1–224.

Goudet SM, Bogin BA, Madise NJ, Griffiths PL. Nutritional interventions for preventing stunting in children (birth to 59 months) living in urban slums in low-and middle-income countries (LMIC). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011695.pub2.

Sguassero Y, de Onis M, Bonotti AM, Carroli G. Community-based supplementary feeding for promoting the growth of children under five years of age in low and middle income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012(6):CD005039. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005039.pub3.

Visser ME, Schoonees A, Ezekiel CN, Randall NP, Naude CE. Agricultural and nutritional education interventions for reducing aflatoxin exposure to improve infant and child growth in low-and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013376.pub2.

Shah D, Sachdev HS, Gera T, De-Regil LM, Peña-Rosas JP. Fortification of staple foods with zinc for improving zinc status and other health outcomes in the general population. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010697.pub2.

Suchdev PS, Peña-Rosas JP, De-Regil LM. Multiple micronutrient powders for home (point-of-use) fortification of foods in pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011158.pub2.

Suchdev PS, Jefferds MED, Ota E, da Silva LK, De-Regil LM. Home fortification of foods with multiple micronutrient powders for health and nutrition in children under two years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;2(2):CD008959. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008959.pub3.

Gera T, Sachdev HS, Boy E. Effect of iron-fortified foods on hematologic and biological outcomes: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(2):309–24. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.111.031500.

Ota E, Hori H, Mori R, Tobe-Gai R, Farrar D. Antenatal dietary education and supplementation to increase energy and protein intake. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000032.pub3.

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. Introduction to meta-analysis. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2021.

Ahmed A, Hoddinott J, Roy S. Food transfers, cash transfers, behavior change communication and child nutrition. Intl Food Policy Res Inst. 2019;1868.

Bandiera O, Burgess R, Das N, Gulesci S, Rasul I, Sulaiman M. Labor markets and poverty in village economies. Q J Econ. 2017;132(2):811–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjx003.

Blakstad MM, Mosha D, Bellows AL, Canavan CR, Chen JT, Mlalama K, et al. Home gardening improves dietary diversity, a cluster-randomized controlled trial among Tanzanian women. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;17(2):e13096. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.13096.

Bonuedi I, Kornher L, Gerber N. Making cash crop value chains nutrition-sensitive: evidence from a quasi-experiment in rural Sierra Leone. SSRN Electron J. 2020. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3603918.

Deininger K, Liu Y. Economic and social impacts of self-help groups in India. World Bank Group; 2009.

Emran MS, Robano V, Smith SC. Assessing the frontiers of ultra-poverty reduction: Evidence from CFPR/TUP, an innovative program in Bangladesh. TUP, An Innovative Program in Bangladesh. 2009.

Haque MA, Choudhury N, Ahmed ST, Farzana FD, Ali M, Naz F, et al. The large-scale community-based programme ‘Suchana ’improved maternal healthcare practices in north-eastern Bangladesh: findings from a cluster randomized pre-post study. Matern Child Nutr. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.13258.

Heckert J, Olney DK, Ruel MT. Is women’s empowerment a pathway to improving child nutrition outcomes in a nutrition-sensitive agriculture program?: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial in Burkina Faso. Soc Sci Med. 2019;233:93–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.05.016.

Marquis GS, Colecraft EK, Sakyi-Dawson O, Lartey A, Ahunu BK, Birks KA, et al. An integrated microcredit, entrepreneurial training, and nutrition education intervention is associated with better growth among preschool-aged children in rural Ghana. J Nutr. 2015;145(2):335–43. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.114.194498.

Pan Y, Smith SC, Sulaiman M. Agricultural extension and technology adoption for food security: evidence from Uganda. Am J Agric Econ. 2018;100(4):1012–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aay012.

Polanin, J.R. and Snilstveit, B., 2016. Converting between effect sizes. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 12(1), pp.1-13.

Sánchez-Meca, J., Marín-Martínez, F., & Chacón-Moscoso, S. (2003). Effect-size indices for dichotomized outcomes in meta-analysis. Psychological methods, 8(4), 448.

Kabeer N, Datta S. Randomized control trials and qualitative impacts: what do they tell us about the immediate and long-term assessments of productive safety nets for women in extreme poverty in West Bengal? (No. 19–199). Working Paper Series. 2020

Roy S, Hidrobo M, Hoddinott J, Ahmed A. Transfers, behavior change communication, and intimate partner violence: postprogram evidence from rural Bangladesh. Rev Econ Stat. 2019;101(5):865–77. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00791.

Roy S, Ara J, Das N, Quisumbing AR. Flypaper effects” in transfers targeted to women: evidence from BRAC’s “Targeting the Ultra Poor” program in Bangladesh. J Dev Econ. 2015;117:1–19.

Kieran C, Gray B, Gash M. Understanding gender norms in rural Burkina Faso: a qualitative assessment. 2018.

Hagan LL, Aryeetey R, Colecraft EK, Marquis GS, Nti AC, University of Ghana, et al. Microfinance with education in rural Ghana: Men’s perception of household level impact. Afr J Food Agric Nutr Dev. 2012;12(49):5776–88. https://doi.org/10.18697/ajfand.49.enam7.

Dolgopolova I, Li B, Pirhonen H, Roosen J. The effect of attribute framing on consumers’ attitudes and intentions toward food: a Meta-analysis. Bio-based Appl Econ J. 2021;10:253–64.

Data4Diets' (2021), International Dietary Data Expansion Project. https://inddex.nutrition.tufts.edu/data4diets. Accessed 4 Sep 2022.

DQQ Tools & Data’ (2021), Global Diet Quality Project. https://www.globaldietquality.org/dqq. Accessed 11 Apr 2022.

Choudhury N, Raihan MJ, Ahmed ST, Islam KE, Self V, Rahman S, Schofield L, Hall A, Ahmed T. The evaluation of Suchana, a large-scale development program to prevent chronic undernutrition in north-eastern Bangladesh. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–9.

Snilstveit, B, Stevenson, J, Langer, L, da Silva, N, Rabat, Z, Nduku, P, Polanin, J, Shemilt, I, Eyers, J, Ferraro, PJ, Incentives for climate mitigation in the land use sector – the effects of payment for environmental services (PES) on environmental and socio-economic outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: a mixed-method systematic review 3ie Systematic Review 44. London: International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie). 2019. https://doi.org/10.23846/SR00044

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2006) 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research. Public Health Resource Unit. Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/supplementary/2046‐4053‐3‐139‐S8.pdf

Das N, Yasmin R, Ara J, Kamruzzaman M, Davis P, Behrman J, et al. How do intrahousehold dynamics change when assets are transferred to women? Evidence from BRACCs challenging the frontiers of poverty reduction targeting the ultra-poor program in Bangladesh. SSRN Electron J. 2013. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2405712.

Huda K, Kaur S. ‘It was as if we were drowning’: shocks, stresses and safety nets in India. Gend Dev. 2011;19(2):213–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2011.592632.

Olney DK, Dillon A, Ruel MT, Nielsen J. Lessons learned from the evaluation of Helen Keller International’s enhanced homestead food production program. Achieving a nutrition revolution for Africa: The road to healthier diets and optimal nutrition. 2016;67–81.

van den Bold M, Dillon A, Olney D, Ouedraogo M, Pedehombga A, Quisumbing A. Can integrated agriculture-nutrition programmes change gender norms on land and asset ownership? Evidence from Burkina Faso. J Dev Stud. 2015;51(9):1155–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2015.1036036.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This project has been commissioned and funded by Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) through its “Knowledge for Nutrition” program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MB contributed to extract the effect sizes and analyze them through the meta-analysis. She was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. MK searched the additional qualitative studies, extracted the data and analyzed them. They were a major contributor in writing the manuscript. CL contributed extract the effect sizes and analyze them through the meta-analysis. She was a major contributor in reviewing and writing the manuscript, as well as in ensuring its overall quality. SS ensured the meta-analysis were conducted following the highest standard and corrected any mistakes. She was a major contributor in reviewing the manuscript, as well as in ensuring its overall quality. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This is not applicable to this manuscript as we did not use primary data.

Consent for publication

This is not applicable as we did not include any individual person’s data in any form.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

It contains additional information about the included studies in terms of Intervention type,Detailed intervention, Evaluation method, Hypotheses mechanisms of action, Impacts Barriers and facilitatorsto impact, implementation, and evaluation, Equity consideration, Sources of bias, Risk of bias, Effectiveness,ans Conclusions.

Appendices

Appendices

Appendix 1: Rapid Evidence Assessment on Women’s Empowerment in Food Systems Interventions – Protocol

Background

The problem, condition, or issue

Women are key actors within food systems, serving as producers, wage workers, traders, processors, and consumers. Women also face differential outcomes related to accessing and affording nutritious foods or a healthy diet. Some evidence shows that women—often living in more vulnerable conditions than men due to societal norms—can improve their own and their children’s nutritional status when they have socio-economic power to make decisions on food and non-food expenditures (especially accessing resources) and can take care of themselves and their families [3]. As a result, women’s empowerment interventions represent a key opportunity to improve nutrition-related outcomes. There is substantial agreement about pathways to improve women’s empowerment in food systems. However, cross-contextual evidence on the factors that cause poorer nutrition outcomes for women, and how women’s empowerment can improve nutritional outcomes is still scant [2].

The interventions

We will include interventions that integrate activities to empower women and/or girls to access, participate and take control in components of the food system, for example improving decision-making on household expenditures. We have extracted relevant papers from the Food Systems and Nutrition evidence gap map that have any intervention component relating to women’s empowerment.

Expected theories of change

Our theory of change is based on the pathways developed by Njuki et al. [2] to presume that women’s empowerment can lead to improved nutrition with a variety of other influencing factors. Gendered food systems interact with gender equality and inequality in a four-dimensional space: individual, systemic, formal, and informal.

Rationale for the review

This rapid evidence assessment is expected to inform decisions regarding gender and women’s empowerment in nutrition and food systems interventions. Given that women’s empowerment has been highlighted as a critical, crosscutting theme for the transformation of the food system [4], key decision-makers have indicated interest in this area. Researchers can use this work to better understand how to intertwine gender-sensitive or -transformative interventions for improved nutritional outcomes.

Research questions

-

1.

What are the effects of women’s empowerment interventions within the food system on the availability, accessibility, and affordability of healthy diets or nutritional status?

-

2.

Are there any unintended consequences of such interventions?

-

3.

Do effects vary by context, approach to empowerment, or other moderators?

Methodology

To respond to these research questions, we will conduct a rapid evidence assessment, based on a systematic literature search of key academic databases. Literature will be screened for quality and summarized visually and in a narrative format. A rapid evidence assessment is based upon the rigorous methodology adopted in a systematic review; however, many steps are shortened [10].

Criteria for including and excluding studies in the review (PICOS)

Criteria | Included | Excluded |

|---|---|---|

Participants | People of any age and gender residing in low- and middle-income countries (L&MICs) | High-income countries |

Intervention(s) | Interventions aimed at increasing women’s empowerment and giving women the capabilities to make decisions on the purchase and consumption of a healthy diet | All else |

Comparison | Business as usual, including pipeline and waitlist controls An alternate intervention | No comparator |

Outcome(s) | Food affordability, accessibility, and availability Iron, zinc, vitamin A, and iodine status Anthropometric measures Diet quality and adequacy Measures of well-being | All else |

Study designs | Experimental, quasi-experimental, systematic reviews and cost evidence | Efficacy trials, before-after with no control group, cross-sectional studies and so on |

Types of study participants

Only studies which consider populations in low- and middle-income countries (as defined using the World Bank Country and Lending Groups classification in first year of intervention or if not available then Publication year) will be considered. The exception to this is if a country held high-income status for only one year before reverting to L&MIC status. These will be included even if the intervention began in the high-income year. As of the writing of this protocol, this applies to Argentina (2014, 2017), Venezuela (2014), Mauritius (2019), and Romania (2019). If the study is conducted in a high-income country but measures impact on people, firms, or institutions in an L&MIC, it can be included. For example, we would not exclude a study that measures impact of New Zealand's immigration visa lottery on residents of Tonga.

Types of interventions

Eligible interventions were identified during the development of the Food Systems and Nutrition Evidence Gap Map [1]. The map defined women’s empowerment interventions as “efforts targeted at increasing women's abilities to make decisions regarding the purchase and consumption of healthy foods.” After completing the search, we found that these interventions were primarily related to agriculture skills training, asset transfers, microcredit, and behavior change.

Citation | Intervention |

|---|---|

Ahmed et al. [24] | The intervention consists of two treatment arms: cash or food transfers, with or without nutrition behavior change communication (BCC), to women living in poverty in rural Bangladesh |

Bandiera et al. [25] | The intervention is a nationwide asset transfer “plus” program in Bangladesh. The intervention transfers livestock assets and skills to the poorest women |

Bonuedi et al. [27] | The intervention is two-pronged: (1) cash crop and (2) nutrition components. (1) Included farmer field schools (FFS), productive inputs, and value chain linkages. (2) Included gender-sensitive nutrition behavior change and awareness creation |

Choudhury et al. [45] | Suchana improves nutrition service delivery, nutrition governance, and the knowledge of women and girls regarding gender norms and gender-based violence that can impact mother and child nutrition |

Deininger et al. [28] | The intervention is self-help groups for women living in poverty in India |

Emran et al. [29] | This is an asset transfer “plus” intervention, bundling asset transfers with capacity building (health, education, and training) for poor women with the goal of helping them graduate to the standard micro-credit program of BRAC |

Heckert et al. [31] | The intervention is the Enhanced Homestead Food Production (E-HFP) program, a nutrition- and gender-sensitive agriculture training program |

Marquis et al. [32] | This is a microcredit “plus” intervention that provides microcredit loans and weekly sessions of nutrition and entrepreneurship education for 179 women with children 2–5 years of age |

Mosha et al. [26] | The agricultural training and provision of inputs intervention includes the provision of small agricultural inputs to women, garden training support, and nutrition and health counselling to improve food security |

Pan et al. [33] | A large-scale agricultural extension program for smallholder women farmers to improve food security in Uganda |

Types of outcome measures

The table below outlines outcome indicators that will be extracted. These outcomes can be measured using a variety of indicators. We have indicated the preferred outcomes and alternate outcomes which could be used if preferred outcomes are not reported. Composite measures will always be preferred over disaggregated ones.

Outcome | Indicators |

|---|---|

Food security | Preferred outcomes: food security indexes and composite scores Secondary outcome: skipped meals Tertiary outcome: reports of insufficient food |

Food affordability | Preferred outcome: per capita food consumption in monetary units Secondary outcome: per capita food consumption in weight Other measures, such as cost of a food basket, will be considered if these are not available |

Food availability/accessibility | Preferred outcomes: food assets, production (community gardens,) and stores Other measures, such as distance and accessibility to markets |

Diet quality and adequacy | Preferred outcomes: composite diet scores such as the nutrient rich food index Secondary outcome: dietary diversity and other food variety measures Tertiary outcome: intake of specific foods |

Anthropometrics | Preferred outcomes: body mass index, weight for length, length for age, weight for age Other measures, such as MUAC and ponderal index, will be considered if these are not available |

Iron, zinc, vitamin A, and iodine status | Preferred outcome: measures of content in blood/tissue (ex. hemoglobin levels) Secondary outcome: intake in weight (grams, micrograms, etc.) Tertiary outcome: intake in percentage relative to recommended intake Other measures will be considered |

Well-being | Preferred outcome: perceived well-being Secondary outcome: anxiety |

Types of comparators

-

Business as usual, including pipeline and waitlist controls

-

An alternate intervention

-

Studies with no comparator are excluded

Types of study design

Experimental, quasi-experimental, systematic review, and cost evidence will be considered. The following study designs will be included.

-

Randomized controlled trial

-

Regression discontinuity design

-

Controlled before-and-after studies, including

-

Propensity-weighted multiple regression

-

Instrumental variable

-

Fixed effects models

-

Difference-in-differences (and any mathematical equivalents)

-

Matching techniques

-

-

Interrupted time series

-

Systematic reviews that include a quantitative or narrative synthesis

Ex-post cost-effectiveness analyses will be included, provided that they are associated with an included impact evaluation.

Date, language, and form of publication

All proceeding restrictions are from the EGM.

-

Date: 2000

-

Language: English

Search strategy

We will not perform any new searches for this REA. Instead, we will look at the ten studies of women’s empowerment interventions identified in the Food Systems and Nutrition 'living’ EGM,Footnote 1 updated every four months (last update December 2021). We specifically searched for interventions using women’s empowerment within the food system implemented in low- and middle-income countries. This EGM was developed through a systematic search and screening process equal to that of a systematic review. However, because interventions had to function within the food system to be included, many women’s empowerment interventions, such as those related to self-help groups broadly, were not included. Ultimately, the EGM includes ten evaluations of women’s empowerment interventions which considered outcomes related to food availability, accessibility, and affordability and nutritional status. We will conduct additional targeted searches to identify qualitative studies and process evaluations of the included interventions.

Selection of studies

Screening

Because we are utilizing the results of the Food systems EGM, there is no search and screening process to select the studies. Rather, within the FSN EGM, we selected ten studies that have women’s empowerment interventions associated with the relevant outcomes.

Data extraction and coding procedures

Data extraction templates will be modified from 3ie’s repository coding protocol and the coding protocols typically used for systematic reviews (Appendix 2). This includes bibliographic, geographic information and substantive data, as well as standardized methods information. In addition, two members of the team will extract data independently on interventions, outcomes, population (including gender/age disaggregation, when available), and effect sizes corresponding to the outcomes indicated above, and any discrepancies will be reconciled. On interventions, outcomes, population (including gender/age disaggregation, when available), and effect sizes corresponding to the outcomes indicated above, and any discrepancies will be reconciled. Qualitative information on barriers and facilitators to implementation, sustainability and equity implications, and other considerations for practitioners will also be extracted.

Critical appraisal

All the included quantitative impact evaluations will be appraised by two independent members of the team using a critical appraisal tool (Appendix 1.1 and 1.2). Qualitative studies linked to included impact evaluations will also be critically appraised.

Qualitative search and appraisal