Abstract

Malaria treatment performance is potentially influenced by pharmacogenetic factors. This study reports an association study between the ABCB1 c.3435C>T, CYP3A4*1B (g.-392A>G), CYP3A5*3 (g.6986A>G) SNPs and artemether + lumefantrine treatment outcome in 103 uncomplicated malaria patients from Angola. No significant associations with the CYP3A4*1B and CYP3A5*3 were observed, while a significant predominance of the ABCB1 c.3435CC genotype was found among the recurrent infection-free patients (p < 0.01), suggesting a role for this transporter in AL inter-individual performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Artemisinin combination therapy (ACT) has contributed to the remarkable decline by 48% in the malaria mortality rate between 2000 and 2015 [1]. The disease remains a major public health challenge, causing over 400,000 deaths annually, partly due to underperforming treatments. The success of malaria treatment depends on many factors, not least inter-individual pharmacokinetic differences, which are potentially influenced by patient pharmacogenetic background [2].

Artemether–lumefantrine (AL) is the most adopted antimalarial by national malaria control programs worldwide. In Angola, it represents the first-line treatment of choice for uncomplicated malaria.

Upon AL oral administration, artemether shows an elimination half-life of 1–3 h, CYP3A4 being the main enzyme involved in its conversion towards the (also active) dihydroartemisinin (DHA) metabolite [3]. Both artemether and DHA act rapidly to clear malaria parasites from circulation, reducing asexual parasite mass [4]. The lumefantrine partner has a half-life of 3–6 days and is responsible for the elimination of parasites remaining from the artemisinin ‘first impact’ action, while preventing recurrent malaria parasitaemia [5]. Only <10% of the absorbed LUM is biotransformed towards the active desbutyl-benflumetol (DBB) metabolite, mainly by CYP3A enzymes [6].

Both lumefantrine and DHA are essentially eliminated through the bile. In the apical biliocanalicular membrane of the hepatocyte, the ABCB1 (MDR1/Pgp) ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter is a major biliary efflux pump, particularly for lipophilic substrates, as lumefantrine [7, 8]. Significant inter-individual variation in drug exposure is known for both artemisinin and lumefantrine, suggesting the potential importance of CYP3A4 and ABCB1 pharmacogenetic characteristics influencing AL performance.

A previous attempt to correlate lumefantrine pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters with CYP3A4 and ABCB1 tag SNPs, particularly the promoter located g.-392A>G in the former (CYP3A4*1B) and the synonymous c.3435C>T in the latter, did not yield significant associations [9], having prompted the natural conclusion that such variation had a negligible effect [9]. Possible positive associations were anyway recently suggested for ABCB1 c.3435C>T with altered LUM exposure among HIV positive subjects under Efavirenz based therapy.

In the present work, we hypothesized that small pharmacokinetic differences might have observable pharmacodynamic consequences, the parasite reaction being a more sensitive parameter of the individual pharmacogenetic influence. Parasite clearance on day 3 post-treatment, recurrent infection prevalence and the 28-day cure rate endpoint of adequate clinical and parasitologic response (ACPR) were herein used as parameters to assess the effect of the patient pharmacogenetic status on AL in vivo anti-parasite performance. To test this hypothesis, a previously performed AL efficacy trial was analysed.

Methods

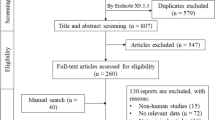

Patients

One-hundred and three unrelated patients with microscopy confirmed (1000–100,000 asexual parasites/µL) uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria involved in an AL (Coartem®, Novartis AG, Basel) efficacy trial in the Luanda region, Angola, conducted during the 2011–2013 period [10]. Briefly, upon informed written consent by the participant or their guardians, patients were treated with weight-adjusted, six-dose AL in 3 days, in accordance with national guidelines [11, 12]. Clinical assessment was performed at D2, D3, D7, D14, D21 and D28. At each time-point, thick blood films were examined for the presence of parasites and a capillary blood sample obtained for PCR analysis.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Angolan National Public Health Institute/Ministry of Health Ethics Committee. All procedures followed the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Molecular genotyping

Capillary blood sample were collected on filter paper (FTA® Classic Card, Whatman). DNA extraction was done by phenol–chloroform methods. The ABCB1 c.3435C>T, CYP3A4 g.-392C>G and CYP3A5 g.6986A>G SNPs were analysed by established PCR–RFLP protocols [13]. Presence of parasitaemia was further tested through the pfmsp2 PCR amplification of all samples at all time spots [10]. Allele frequencies of the analysed SNPs were compared between groups of patients in accordance with two different treatment outcome phenotypes: (a) pfmsp2 positive PCR by D3, informative concerning the artemisinin partner performance, in accordance with WHO guidelines; and, (b) pfmsp2 positive PCR during the 28-day follow up (lumefantrine prophylactic effect). The number of clinical failure events (PCR-corrected recrudescence) was too small to warrant their specific analysis. All recrudescences were included in the general recurrence group.

Genotyping data for the parasite pfmdr1N86Y SNP, a well-established factor in parasite in vivo response to AL [14, 15], was available through previously performed PCR–RFLP methods [10].

Statistical analysis

Data on SNPs were analysed using IBM SPSS version 23. Chi square (χ 2) test and Z statistics were used to determine significant differences between proportions (Graphpad Prism® 7, Graphpad Software Inc, La Jolla, CA, USA). Five individual associations were herein tested: recurrence vs CYP3A4*1B allele status, recurrence vs ABCB1 c3435C>T SNP status, recurrence vs CYP3A5*3 SNP status, D3 positivity vs CYP3A4*1B SNP status, and D3 positivity vs ABCB1 c.3435C>T SNP status). Accordingly, a Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold at p < 0.01 was considered for these tests. Multivariate Log-linear analysis was performed in order to specifically investigate associations of key three categorical variables: (a) D28 follow-up outcome (recurrence), (b) ABCB1/MDR1 c.3435C>T genotype, and (c) pfmdr1 N86Y status of the initial infection. The multiple testing was Benjamini–Hochberg corrected, assuming a 10% false discovery rate (q).

Results

The 28-day PCR-corrected cure rate was 91.3%. On D3, 46.6% (n = 48) had positive PCR. During the 28-day follow up, 29/103 patients experienced recurrent parasitaemia, as detected through PCR. Ninety-eight patients were successfully analysed for the CYP3A4 -392A>G SNP. The genotype frequency in this Angolan population was 0.112 (0.060–0.196, 11/98) for the wild type (g.-392AA), 0.541 (0.438–0.641, 53/98) minor allele homozygous (g.-392GG) and 0.347 (0.438–0.641, 34/98) for the heterozygous (g.-392AG). The population was found in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium for this locus (p > 0.05).

The patient CYP3A4*1B genotype was not found to be significantly associated with either D3 parasite positivity (χ 2 = 5.493, df = 1, p = 0.019) (Table 1) or treatment outcome upon the 28-day follow up (χ 2 = 2.378, df = 1, p = 0.123) (Table 2).

Concerning the ABCB1 c.3435C>T SNP, 101 patients were successfully tested. Genotype frequencies were 0.762 (0.667–0.841, 77/101) for the wild type (c.3435CC), 0.079 (0.035–0.150, 8/101) for the minor allele homozygous (c.3435TT) and 0.158, (0.093–0.244, 16/101) for the heterozygous (c.3435CT). The population was found in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium for this locus (p > 0.05).

The c.3435C>T SNP was also not significantly associated with the D3 parasite PCR positivity (χ 2 = 0.883, df = 1, p = 0.347) (Table 1). On the other hand, c.3435TT genotypes were found to be significantly more frequent among patients experiencing recurrent events during follow-up (χ 2 = 6.9693, df = 1, p = 0.008) (Table 3, Fig. 1). These changes were further reflected on a significant increase in recurrence risk (OR = 10.59, 1.96–57.30, z-score = 2.739, p = 0.006) in this subgroup.

During the completion of the present work, a new report has suggested CYP3A5 as a contributor to lumefantrine metabolism [16]. Following this lead, we have successfully analyzed CYP3A5*3 (c.6986A>G) in 84 samples, as this is the allele is the most investigated as having a robust deleterious effect in the expression of the gene [17]. Genotype frequencies were 0.750 (0.644–0.838, 63/84) for the wild type (c.6986AA), 0.048, (0.013–0.117, 4/84) for the heterozygous (c.6986AG) and 0.202 (0.123–0.304, 17/84) for the minor allele homozygous (c.6986GG). The sample population was found in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium for this locus (p > 0.05).

As with CYP3A4*1B, no significant association was observed between the patient status for carrying a CYP3A5*3 alleles and the parasitological outcome during the 28 day follow up (χ 2 = 0.932, df = 1, p = 0.335)(Table 2).

Due to the size limitations of the study, multivariate analysis was limited to variables expected to interact concerning the clinical outcome under focus (D28 follow up positivity), namely the ABCB1 c3435C>T status and the pfmdr1 N86Y status. A subset of 92 cases was available with complete data for these three variables (Table 4).

Upon the assumption of a false discovery rate of (q) of 10% for Benjamini–Hochberg multiple test correction, only two associations stood out as near the threshold of significance: the overall interaction between the three analysed variables (G2 = 10.84, df = 4, p = 0.0284 vs p (corrected) = 0.0286), and the association between recurrence during follow-up and the ABCB1 c3435C>T status (G2 = 8.36, df = 2, p = 0.0146 vs p (corrected) = 0.0143), after filtering the effect of the presence/absence of the pfmdr1 N86 allele (Table 4). This analysis further suggests the importance of the ABCB1 c3435C>T SNP, albeit the limited number of samples available recommends caution in the interpretation of the results.

Discussion

The present work focused on finding links between patient CYP3A and ABCB1 pharmacogenetics and AL pharmacodynamics in vivo endpoints. D3 positivity was not significantly associated with the patient CYP3A4*1B status (Table 1), an observation that can be simply explained by the fact that DHA-the main artemether CYP3A4 metabolite-is also highly active against P. falciparum parasites. Pharmacogenetic driven variable rates of artemether to DHA bioconversion are likely not to be readily visible in terms of the artemisinin effect on the infection. As for the ABCB1 c.3435C>T, the negative observations possibly result from the specific capacity of this transporter to efflux more lypophilic compounds then the final phase II glucuronidated DHA extracted from the liver.

The CYP3A4*1B and CYP3A4*3 status were not seen to influence the risk of malaria recurrence. The AL post-treatment protective effect is essentially related with the action of lumefantrine, the long half-life partner. In regular conditions, it is expected that the large majority of lumefantrine is eliminated unchanged [18], a result supported by the previously observed modest effect of ketoconazole in interaction studies [6]. This means that any role of CYP3A4 and/or CYP3A5 will be limited to variations in this remain biotransformed fraction, which expected small size might have precluded its detection during the present works. One cannot nevertheless rule out the possibility that small changes in the concentrations of the resulting DBB metabolite might influence the treatment, in particular because of its higher anti-parasitic potency, as previously suggested [19]. Also, it is likely that scenarios of long-term CYP3A induction might increase the fraction of LUM metabolism-as potentially observed among patients under Efavirenz therapy [20]-and as such the role of this cytochrome P450s on lumefantrine elimination. Nevertheless, inside its size limitations and in this specific population, our study suggests a likely minor contribution of the CYP3A4*1B and CYP3A5*3 SNPs in modulating AL post-treatment prophylactic action.

A significant increase in the frequency of the ABCB1 c.3435TT genotype was found among patients suffering recurrent infections during the 28-day follow up, suggesting a role of the encoded P-glycoprotein. The synonymous c.3435C>T polymorphism has been proposed to be linked with altered rates of protein synthesis, leading to proteins that albeit having the same primary sequence, emerge from the process of translation with different tertiary conformations [21]. The functional effect of such changes in the P-glycoprotein seems to depend on the drug under consideration. In the present studies, a substantial predominance was found of the ABCB1 c.3435CC genotype among the recurrence-free patients, signalling an increased lumefantrine exposure associated with this genotype, which better shielded the recovering patients from new infections.

A shortcoming of the present study is the unavailability of pharmacokinetic data, namely D7 LUM levels, in order to have a complete pharmacokinetic/pharmacogenetic picture. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that the present results are in agreement with recent data from Maganda et al. [20], where the ABCB1 c.3435TT genotype, was suggested to be associated with a significantly decreased D7 lumefantrine levels among patients undergoing malaria treatment with AL. Such an effect in drug exposure can explain the increase risk of these patients towards recurrent infection.

These data suggest lumefantrine as part of the group of ABCB1 substrates where this genotype is associated with increased drug exposure, probably due to a less efficient efflux. Other examples include tacrolimus [22, 23], silibinin [24], amlodipine [25], or in some studies, digoxine [26].

Conclusion

By exploring potential pharmacodynamics/pharmacogenetic associations in anti-malarial therapy, this report shows a non-negligible influence of the host ABCB1 c.3435C>T SNP in the performance of artemether–lumefantrine. The present observations join other recent reports pointing for the importance drug transporter pharmacogenetics in ACT pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics [20, 27].

References

World Health Organization. World malaria report 2015. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

Dandara C, Swart M, Mpeta B, Wonkam A, Masimirembwa C. Cytochrome P450 pharmacogenetics in African populations: implications for public health. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2014;10:769–85.

Piedade R, Gil JP. The pharmacogenetics of antimalaria artemisinin combination therapy. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2011;7:1185–200.

World Health Organization. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. 3rd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005.

Djimdé A, Lefèvre G. Understanding the pharmacokinetics of Coartem. Malar J. 2009;8(Suppl 1):S4.

Lefèvre G, Carpenter P, Souppart C, Schmidli H, McClean M, Stypinski D. Pharmacokinetics and electrocardiographic pharmacodynamics of artemether-lumefantrine (Riamet) with concomitant administration of ketoconazole in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54:485–92.

Raju KS, Singh SP, Taneja I. Investigation of the functional role of P-glycoprotein in limiting the oral bioavailability of lumefantrine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:489–94.

Oga EF, Sekine S, Shitara Y, Horie T. Potential P-glycoprotein-mediated drug-drug interactions of antimalarial agents in Caco-2 cells. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87:64–9.

Staehli-Hodel EM, Csajka C, Ariey F, Guidi M, Kabanywanyi AM, Duong S, et al. Effect of single nucleotide polymorphisms in cytochrome P450 isoenzyme and N-acetyltransferase 2 genes on the metabolism of artemisinin-based combination therapies in malaria patients from Cambodia and Tanzania. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:950–8.

Kiaco K, Teixeira J, Machado M, do Rosário V, Lopes D. Evaluation of artemether-lumefantrine efficacy in the treatment of uncomplicated malaria and its association with pfmdr1, pfatpase6 and K13-propeller polymorphisms in Luanda, Angola. Malar J. 2015;14:504.

WHO. World malaria report 2016. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

Fançony C, Brito M, Gil JP. Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance in Angola. Malar J. 2016;15:74.

Cavaco I, Gil JP, Gil-Berglund E, Ribeiro V. CYP3A4 and MDR1 alleles in a Portuguese population. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2003;41:1345–50.

Malmberg M, Ferreira PE, Tarning J, Ursing J, Ngasala B, Björkman A, et al. Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance phenotype as assessed by patient antimalarial drug levels and its association with pfmdr1 polymorphisms. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:842–7.

Venkatesan M, Gadalla NB, Stepniewska K, Dahal P, Nsanzabana C, Moriera C, et al. Polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter and multidrug resistance 1 genes: parasite risk factors that affect treatment outcomes for P. falciparum malaria after artemether-lumefantrine and artesunate-amodiaquine. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;91:833–43.

Mutagonda RF, Kamuhabwa AAR, Minzi OMS, Massawe SN, Asghar M, Homann MV, et al. Effect of pharmacogenetics on plasma lumefantrine pharmacokinetics and malaria treatment outcome in pregnant women. Malar J. 2017;16:267.

Kuehl P, Zhang J, Lin Y, Lamba J, Assem M, Schuetz J, et al. Sequence diversity in CYP3A promoters and characterization of the genetic basis of polymorphic CYP3A5 expression. Nat Genet. 2001;27:383–91.

Cousin M, Kummerer S, Leefvre G, Marrast AC, Stein D, Weaver M. Coartem (artemether-lumefantrine) tablets for the treatment of malaria in patients with acute, uncomplicated infections due to Plasmodium falciparum or mixed infections including P. falciparum. Advisory Committee Briefing Book, Novartis, October 2008.

Wong RP, Salman S, Ilett KF, Siba PM, Mueller I, Davis TM. Desbutyl-lumefantrine is a metabolite of lumefantrine with potent in vitro antimalarial activity that may influence artemether-lumefantrine treatment outcome. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1194–8.

Maganda BA, Minzi OM, Ngaimisi E, Kamuhabwa AA, Aklillu E. CYP2B6*6 genotype and high efavirenz plasma concentration but not nevirapine are associated with low lumefantrine plasma exposure and poor treatment response in HIV-malaria-coinfected patients. Pharmacogenom J. 2016;16:88–95.

Kimchi-Sarfaty C, Oh JM, Kim IW, Sauna ZE, Calcagno AM, Ambudkar SV, et al. A “silent” polymorphism in the MDR1 gene changes substrate specificity. Science. 2007;315:525–8.

Cheung CY, Op den Buijsch RA, Wong KM, Chan HW, Chau KF, Li CS, et al. Influence of different allelic variants of the CYP3A and ABCBI genes on the tacrolimus pharmacokinetic profile of Chinese renal transplant recipients. Pharmacogenomics. 2006;7:563–74.

Kravljaca M, Perovic V, Pravica V, Brkovic V, Milinkovic M, Lausevic M, et al. The importance of MDR1 gene polymorphisms for tacrolimus dosage. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2016;83:109–13.

Tan ZR, Zhou YX, Liu J, Huang WH, Chen Y, Wang YC, et al. The influence of ABCB1 polymorphism C3435T on the pharmacokinetics of silibinin. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2015;40:685–8.

Kim KA, Park PW, Park JY. Effect of ABCB1 (MDR1) haplotypes derived from G2677T/C3435T on the pharmacokinetics of amlodipine in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:53–8.

Sakaeda T, Nakamura T, Horinouchi M, Kakumoto M, Ohmoto N, Sakai T, et al. MDR1 genotype-related pharmacokinetics of digoxin after single oral administration in healthy Japanese subjects. Pharm Res. 2001;18:1400–4.

Vos K, Sciuto CL, Piedade R, Ashton M, Björkman A, Ngasala B, Mårtensson A, Gil JP. MRP2/ABCC2 C1515Y polymorphism modulates exposure to lumefantrine during artemether-lumefantrine antimalarial therapy. Pharmacogenomics. 2017;18:981–5.

Authors’ contributions

KK participated in the design and implementation of the study in Angola, molecular laboratory work and analysis, data analysis and drafting the manuscript; JPG participated in the analysis of the data, manuscript writing and review; VR and AR reviewed the manuscript, and DL conceived, coordinated and supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We are sincerely grateful to the patients and parents or guardians of the children involved in the study, as well as the staff of hospitals who participated in sample collection, in particular Mrs Pedro Mbanzulu and Manuel Teca; we thank Lieutenant-General Aires Africano and Lieutenant-General Alcibiades Chindombe of the Angolan Armed Forces for the funding support, as well as Dr. Filomeno Fortes, Dr. Vanda Loa and the Catholic priest Fernando Tchilunda for the useful support provided at the field level. This study received funding from the Angolan Armed Forces. This work was in part funded by the Swedish Research Council Grant Ref. VR-2014-3134.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Angolan National Public Health Institute/Ministry of Health Ethics Committee. All procedures followed the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Funding

This study had a financial support from the Angolan Armed Forces in form of tuition fee allocated to KK. This work was in partly funded by the Swedish Research Council Grant Ref. VR-2014–3134.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kiaco, K., Rodrigues, A.S., do Rosário, V. et al. The drug transporter ABCB1 c.3435C>T SNP influences artemether–lumefantrine treatment outcome. Malar J 16, 383 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-017-2006-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-017-2006-6