Abstract

Background

HIV and malaria are among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality during pregnancy in Africa. However, data from Congolese pregnant women are lacking. The aim of the study was to determine the magnitude, predictive factors, clinical, biologic and anthropometric consequences of malaria infection, HIV infection, and interactions between malaria and HIV infections in pregnant women.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted among pregnant women admitted and followed up at Camp Kokolo Military Hospital from 2009 to 2012 in Kinshasa, the Democratic Republic of Congo. Differences in means between malaria-positive and malaria-negative cases or between HIV-positive and HIV-negative cases were compared using the Student’s t-test or a non-parametric test, if appropriate. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, if appropriate. Backward multivariable analysis was used to evaluate the potential risk factors of malaria and HIV infections. The odds ratios with their 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were estimated to measure the strengths of the associations. Analyses resulting in values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

A malaria infection was detected in 246/332 (74.1%) pregnant women, and 31.9% were anaemic. Overall, 7.5% (25/332) of mothers were infected by HIV, with a median CD4 count of 375 (191; 669) cells/μL. The mean (±SD) birth weight was 2,613 ± 227 g, with 35.7% of newborns weighing less than 2,500 g (low birth weight). Low birth weight, parity and occupation were significantly different between malaria-infected and uninfected women in adjusted models. However, fever, anemia, placenta previa, marital status and district of residence were significantly associated to HIV infection.

Conclusion

The prevalence of malaria infection was high in pregnant women attending the antenatal facilities or hospitalized and increased when associated with HIV infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malaria is well established as a major global health problem worldwide [1,2]. Malaria, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and tuberculosis are among the three most important global health problems of developing countries. Both of them together, cause more than four million deaths per year [2]. The co-infection exists in many parts of the world. This is particularly true in sub-Saharan Africa, where an estimated 40 million people are living with HIV and more than 350 million episodes of malaria occur yearly [1]. Malaria and HIV infections are also the most deleterious conditions in sub-Saharan African pregnant women, in terms of the morbidity and mortality they cause in mothers and their newborns [3-9].

In the DRC, malaria is reported to be the principal cause of morbidity and mortality, especially among vulnerable population like pregnant women and children less than five years of age. Close to 70% of all outpatient health care visits and an average of 30% of hospital admissions are malaria-related [10]. A recent study in the DRC based on Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) in 2007 showed an increase risk for malaria in certain populations and regions of the DRC with higher prevalence in rural area than urban [11]. In 2003, UNAIDS estimated that the prevalence of HIV in adult in DRC was 4.2% and 1.1 million people were living with HIV/AIDS [12]. However, this prevalence among pregnant women was ranged from 2.7 to 5.4% in 1999 in urban area and 8.5% in rural area [12].

Understanding the epidemiology of malaria and HIV during pregnancy is important for deciding the best control strategies. Unfortunately, vital registration systems in sub-Saharan African countries have low coverage and do not produce accurate estimation of this co-infection. Health workers in the Congolese Army are unable to identify high or risk factors for both malaria and HIV infections so as to tailor interventions and do effective health monitoring. Moreover, pregnant women married to soldiers and single soldiers are habitually facing war-related poverty and human movements. Therefore, the study aims were to determine the magnitude, predictive factors, clinical, biologic and anthropometric consequences of malaria infection, HIV infection, and interactions between malaria and HIV infections in pregnant women.

Methods

Study design

A prospective study for the prevalence of malaria, HIV infection, HIV co-infection, and low birth weight from pregnancy to delivery as well as a comparative study of health consequences at the delivery was conducted from 2009 to 2012.

Study site

The Camp Kokolo Military Hospital (HMRK) was the study setting and is the largest public hospital in the country, situated at the western part of Kinshasa, the capital city of DRC. The town covers an area of 9,965.21 km2 with an estimated total population of 7,411,989 of whom more than 50% are female [13]. The HMRK provides antenatal services and has a well-established prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) programme.

Study population

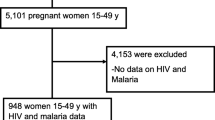

All pregnant women who were suspected of malaria and followed up in routine antenatal care service at HMRK or hospitalized in the same hospital with at least one antenatal visit between 2009 and 2012 were included to this study (Figure 1).

Ethics statement

The institutional review boards and the Ethics Committee of the University Protestant of Kinshasa approved the protocol of the study (CEUPC 0018), which was conducted in compliance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration II. Patients were informed about the research purposes and gave written informed consent. The Ethics Committee of the Université Protestante du Congo (UPC) approved the consent procedure. The guidance of this study was in the context of the routine diagnosis and of normal medical care. Limited epidemiological, clinical and biological information were collected anonymized. Blood samples collection were also performed in the context of the routine diagnosis and of normal medical care for which the department of Tropical Medicine was granted the agreement N/Réf: 007/UPC/SGAC/MM/AB/2009 from the Medical faculty of UPC and the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Kinshasa.

Data collection

Mothers were interviewed to obtain socio-demographic, biographic, and clinical variables. These pregnant women were tested using both blood films (thin and thick blood smear) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the presence of Plasmodium, responsible for malaria cases. Study participants who were positive for malaria were treated. All mothers were provided a standard counseling and were systematically screened for the presence of HIV antibody by using Determine HIV 1/2 rapid test kits (Abbott Diagnostic Division, Hoofddorp, The Netherlands). At the delivery, birth weights of newborns were recorded using standard methods.

Definitions

The demographic details recorded were: age on admission classified as follows: < 20 years, 20–24 and ≥ 25 years, marital status (married spouses of soldiers vs. single women as parents of soldiers), occupation (housewives without income vs. others with income), and the district of residence (urban for Funa, semi-urban for Amba, and Rural for Lukunga). The laboratory variables were: haemoglobin concentration (g/dL) and parasitaemia (parasites/μL). Clinical variables were: history of fever, body aches defines as the combination of asthenia and muscle pain, headaches, nausea and vomiting, bleeding, respiratory tract infection (rhinorrhoea and cough), placenta previa, digestive disorders with gastritis, constipation, diarrhoea and Salmonella infection.

Statistical analysis

The variables were summarized as frequencies, means (standard deviation = SD), medians (interquartile range = IQR). Differences in means between malaria-positive and malaria-negative cases or between HIV-positive and HIV-negative cases were compared using the Student’s t-test or a non-parametric test, if appropriate. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, if appropriate. Backward multivariable analysis was used to evaluate the potential risk factors of malaria and HIV infections. The odds ratios with their 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were estimated to measure the strengths of the associations. Analyses resulting in values of P < 0.05 were considered significant. All reported p-values were two-tailed using Stata, version 12 (Stata Corp, College station, Texas).

Results

Characteristics of the study population

Over the study period, a total of 1,200 pregnant women attended the routine antenatal care services or hospitalized at MRHCK were screened, out of whom 348 were eligible for the study. Out of these, 332 agreed to participate (95.4%) and were tested for malaria and HIV infections (Figure 1). Most of the women that participated in the study were housewives (88.8%) and were married (84.6%). The mean (±SD) age of participants was 28.6 ± 6.1 years and the median number of previous pregnancies, number of children and abortion was three (range 2–5), two (range 2–4) and two (range 1–3), respectively. Additionally, around 40% were in the first trimester of pregnancy. Overall, the mean (±SD) birth weight was 2613 ± 227 g, with 35.7% of newborns weighed less than 2,500 g.

Clinical examination and laboratory assessments of malaria in pregnant women admitted to the study

The overall malaria parasite proportion was 74.1% (246/332) and Plasmodium falciparum was the only species detected in the positive malaria slide of pregnant women whose peripheral blood smears were tested. Of the 332 pregnant women whose hemoglobin levels were analyzed at enrolment, 31.9% (106/332) were anaemic (Hb < 11.0 g/dL). Out of the 332 pregnant women who were interviewed, 37.9% (126/332) had fever, 14.9% (49/332) had headache and 3.5% (38/332) complained of general body weakness whereas 39.8% (132/332) had respiratory tract infection. Other symptoms included nausea 7.5% (25/332), digestive disorder 10.5 (35/332) and bleeding 6.9% (23/332). The geometric parasite density and the 95% confidence interval (CI) in patients with positive slide were 3383 (IQR = 2038-5618) parasites/μL.

Predictive factors associated with incident malaria infection

Table 1 summarizes the risk factors associated with malaria infection in pregnant women using univariate analysis. There was a significant association between urban/Funa district, lack of income in housewives, higher parity with ≥3 children, and incident malaria infection. Low birth weight was more prevalent in presence of malaria than in absence of malaria, the difference being statistically significant. In contrast, the rest of variables of interest were not associated (p > 0.05) with malaria presence. In multivariate analysis, after adjusting for confounder residence, lack of income in housewives (adjusted odds ratio = 3.3 95%CI 1.6 to 6.6; p < 0.001) and higher parity (adjusted odds ratio = 1.9 95%CI 1.1 to 3.3; p = 0.04) remained significantly associated with incident malaria infection.

Prevalence of HIV-infection

Figure 2 shows the interrelationship between malaria infection and HIV-infection. Of the 332 patients enrolled, 7.5% (25/332) were HIV-infected, with a median CD4 count of 375 (IQR = 191–669) cells/μL. Nineteen women (6%) were both infected by malaria and HIV and six (2%) were only infected by HIV. Table 2 summarizes the levels of different associations between variables of interest and HIV-infection. Only single marital status, urban residence, fever, placenta previa, and anaemia were significantly associated with HIV-infection. However, there was no significant difference in rates of other variables of interest between HIV-positive and HIV-negative groups. In multivariate analysis and after adjusting for confounders, placenta previa, fever, anaemia, marital status, and urban residence were significantly and independently associated with the presence of HIV-infection (Table 2).

Contributing factors of low birth weight

Except of malaria infection, the rest variables were not associated (P > 0.05) with (Table 3).

Roles of interactions between malaria and HIV infections on variables of interest

Table 4 presents the comparisons of rates of variables of interest across malaria alone, HIV-infection alone, malaria + HIV-infections, and non-infected groups. The highest proportions of low birth weight, fever, and anaemia were significantly concurrent in the interactions between malaria and HIV-infections.

Discussion

Pregnancy is associated with increased susceptibility to malaria in areas where malaria is endemic [14,15]. The control of malaria and HIV in pregnant sub-Saharan African women has, however, been particularly challenging [16]. However, rare epidemiological data have been recorded in the DRC, where P. falciparum malaria is highly endemic [11]. This paper describess the prevalence of malaria and HIV infections of pregnant women whose peripheral blood smears were tested.

Malaria infection

The proportion of malaria infection in pregnancy in this study was 74.1% in Kinshasa where malaria transmission is perennial and represents a substantial burden for the local population [11]. This prevalence value is relatively consistent with those found in previous studies. However, there is a large range of previously reported prevalence values. For example, estimates of malaria in pregnancy range from 6.8% in Calabar (Nigeria) to 57.5% in Libreville (Gabon) [17,18]. The applicability of these prevalence rates is limited and muss be interpreted with caution since several articles investigating the prevalence of infection disease have cited the lack of national representation as a weakness. The results of this study revealed consistently higher association between malaria and occupation. Further evidence of the relationships between occupation and malaria infection were found in a study with a significantly higher prevalence of malaria parasites in a low socio-economic status occupational category [19-21].

By contrast with several study, fever was not significantly associated with malaria infection in the following study during pregnancy despite the fact that in endemic areas asymptomatic Falciparum infections are frequent in adults [21-23]. Fever alone remains a poor discriminator of malaria infection, suggesting that all fevers should be tested to confirm or refute the role of malaria in the febrile presentation [22]. This result may be due to some comorbidity.

HIV-infection

The prevalence of HIV infection was 7.5% in the present study. This result is higher than the previous 4.2% reported in DRC by UNAIDS in 2003 [12]. A number of factors that facilitate further the spread of HIV in DRC included ignorance which refers to the lack of information, fear and stigma, the flux of refugees and soldiers, scarcity and high cost of safe blood transfusions in rural areas, few HIV testing sites, and low availability of condoms outside Kinshasa [12].

The impact of HIV/AIDS and Malaria in pregnant women

The prevalence of HIV infection was associated to malaria in 5.7% (Figure 2). Malaria prevalence increased considerably in HIV-infected women to reach 76.0%. In areas with stable malaria transmission like DRC, HIV increases the risk of malaria infection and clinical malaria in adults, especially in those with advanced immunosuppression. In addition, HIV-infected adults are at increased risk of complicated and severe malaria and death [3-9,17,23].

Every year, approximately 25 million women become pregnant in sub-Saharan Africa, where malaria is endemic, and are at increased risk of infection with P. falciparum, particularly in their first two pregnancies [23]. Interactions between the two infections can have serious consequences, particularly for pregnant women. HIV-infected pregnant women who become infected with malaria are at increased risk of all the adverse outcomes of malaria in pregnancy. Co-infected pregnant women are more likely to have symptomatic malaria infections, anaemia, placental malaria infection, and low birth weight. Epidemiological studies assessing the impact of placental malaria on mother-to-child transmission of HIV have thus far been inconsistent [3-9,17,23].

Risk factors of HIV infection

On multivariate analysis, HIV-infection was significantly associated with fever, anaemia, placenta previa, marital status, and district of residence. This finding characterized the impact of anaemia and fever related to P. falciparum malaria and HIV infection in pregnant women. It has been shown that many studies in Africa shows that co-infection with HIV influences the burden of malaria in pregnancy. HIV increases the degree to which malaria is associated with severe anemia and low birth weight beyond the effect of HIV itself on these outcomes. HIV also puts women of all gravidities at risk for placental infection with malaria, not only women in their first or second pregnancy [3-5,7-9,15,23]. In addition, higher HIV prevalence rates exceeding sometime 40% have been reported among pregnant women in malaria endemic region of Africa [24]. Unfortunately, the analysis of this study did not show a significant association between malaria and HIV infections (p = 0.8). This can be explained by the low number of HIV-infected patients.

Low birth weight

LBW was highly associated to malaria infection in pregnant women. It is estimated that in areas where malaria is endemic, around 19% of infant LBWs are due to malaria and 6% of infant deaths are due to LBW caused by malaria [25,26].

Limitations

Although the present study has yielded some important preliminary findings in regard of malaria and HIV infections in pregnant women in DRC, its design is not without flaws. A number of caveats need to be noted regarding the present study. First, as a cross-sectional design, it does not allow us to make any causal inferences from these findings. Second limitation concerns the restriction of the inclusion criteria and the absence of real follow-up due to the difficulty to enroll patients. Third, there were a relatively small number of HIV-infected pregnant women. While 332 patients were initially enrolled, only 5.7% were infected. In that case, it was relevant to examine the association between HIV-infected women and uninfected women in depth. Furthermore, the lack of unmeasured factors may bias these results. Another limitation was the challenge to collected data. Most women in this study were uneducated and were embarrassed to answer questions. In other cases, data in registers were absent or poorly reported.

Clinical implications and perspectives of Public Health for Malaria in pregnancy

The present findings will impact on clinical practice and public health related to malaria in pregnant women. In obtaining as much relevant socioeconomic information (income, poor nutrition, residence, indoor pollution, HIV-infection, tuberculosis) as possible, present results will help to understand the pathophysiology and to apply the epidemiology evidence in clinical practice and public health. The consequences of socioeconomic deprivation on pregnancy outcomes are anaemia and low birth weight [27]. Policy makers are invited to improve social status and income levels of pregnant women married to soldiers at curbing the high burden of malaria itself and malaria adverse (anaemia and low birth weight). As recommended by the WHO, [28] the United Nations Joint Program programme on HIV/AIDS and different authors, future Congolese Studies will assess effectiveness of co-trimoxazole to prevent malaria in HIV-positive pregnant women [29,30].

Prevention of malaria in Congolese pregnant women might rely on intermittent preventive treatment with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine, which reduces higher probability of placental parasitaemia, anaemia, and low birth weight [31,32]. Thus, good clinical practice will avoid IPT-SP-related resistance and initiation of IPT-SP before 16 weeks of pregnancy [33]. Furthermore, co-trimoxazole provides coverage for opportunistic HIV-associated infections and anti-malarial activities [34].

Conclusions

There is evidence of high prevalence of malaria and HIV infections in Congolese pregnant women. Prevention and surveillance of infectious diseases progression are needed to reduce the incidence of malaria and HIV infections in pregnant women in DRC by improving better management and public health panel control. Qualitative research should be encouraged to obtain more in depth, locally-relevant, and descriptive data examining the impact of infectious diseases in DRC.

Abbreviations

- UPC:

-

Protestant University of Congo

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- DRC:

-

Democratic Republic of Congo

- UNAIDS:

-

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS

- HMRK:

-

Camp Kokolo Military Hospital

- PMTCT:

-

Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- LBW:

-

Low birth weight

References

Hewitt K, Steketee R, Mwapasa V, Whitworth J, French N. Interactions between HIV and malaria in non-pregnant adults: evidence and implications. AIDS. 2006;20:1993–2004.

WHO. Malaria and HIV interactions and their implications for public health policy. available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/prev_care/malariahiv.pdf. 2011.

De Beaudrap P, Turyakira E, White LJ, Nabasumba C, Tumwebaze B, Muehlenbachs A, et al. Impact of malaria during pregnancy on pregnancy outcomes in a Ugandan prospective cohort with intensive malaria screening and prompt treatment. Malar J. 2013;12:139.

Ivan E, Crowther NJ, Mutimura E, Osuwat LO, Janssen S, Grobusch MP. Helminthic infections rates and malaria in HIV-infected pregnant women on anti-retroviral therapy in Rwanda. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2380.

Laar AK, Grant FE, Addo Y, Soyiri I, Nkansah B, Abugri J, et al. Predictors of fetal anemia and cord blood malaria parasitemia among newborns of HIV-positive mothers. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:350.

Mayor A, Kumar U, Bardaji A, Gupta P, Jimenez A, Hamad A, et al. Improved pregnancy outcomes in women exposed to malaria with high antibody levels against Plasmodium falciparum. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:1664–74.

Sappenfield E, Jamieson DJ, Kourtis AP. Pregnancy and susceptibility to infectious diseases. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:752852.

Tonga C, Kimbi HK, Anchang-Kimbi JK, Nyabeyeu HN, Bissemou ZB, Lehman LG. Malaria risk factors in women on intermittent preventive treatment at delivery and their effects on pregnancy outcome in Sanaga-Maritime, Cameroon. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65876.

Turner AN, Tabbah S, Mwapasa V, Rogerson SJ, Meshnick SR, Ackerman WE, et al. Severity of maternal HIV-1 disease is associated with adverse birth outcomes in Malawian women: a cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64:392–9.

WHO. World Malaria Report 2008. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

Messina JP, Taylor SM, Meshnick SR, Linke AM, Tshefu AK, Atua B, et al. Population, behavioural and environmental drivers of malaria prevalence in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Malar J. 2011;10:161.

USAID. Health Profile: Democratic Republic of the Congo. 2004.

Institut National de la Statistique R. L’Institut National de la Statistique de la RDC pour l’année 2004. 2004.

McGregor IA. Epidemiology, malaria and pregnancy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1984;33:517–25.

Modia O’Yandjo A, Foidart JM, Rigo J. [Influence of HIV-1 and placental malaria co-infection on newborn biometry and Apgar scores in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo](in French). J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2011;40:460–4.

Brentlinger PE, Behrens CB, Micek MA. Challenges in the concurrent management of malaria and HIV in pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:100–11.

Bouyou-Akotet MK, Ionete-Collard DE, Mabika-Manfoumbi M, Kendjo E, Matsiegui PB, Mavoungou E, et al. Prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum infection in pregnant women in Gabon. Malar J. 2003;2:18.

Uko EK, Emeribe AO, Ejezie GC. Malaria infection of the placenta and Neonatal Low Birth Weight in Calabar. J Med Lab Sci. 1998;7:7–20.

Carme B, Plassart H, Senga P, Nzingoula S. Cerebral malaria in African children: socioeconomic risk factors in Brazzaville, Congo. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;50:131–6.

Koram KA, Bennett S, Adiamah JH, Greenwood BM. Socio-economic risk factors for malaria in a peri-urban area of The Gambia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89:146–50.

Tshikuka JG, Scott ME, Gray-Donald K, Kalumba ON. Multiple infection with Plasmodium and helminths in communities of low and relatively high socio-economic status. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1996;90:277–93.

Okiro EA, Snow RW. The relationship between reported fever and Plasmodium falciparum infection in African children. Malar J. 2010;9:99.

ter Kuile FO, Parise ME, Verhoeff FH, Udhayakumar V, Newman RD, van Eijk AM, et al. The burden of co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and malaria in pregnant women in sub-saharan Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71(2 Suppl):41–54.

Cock KM, Weiss HA. The global epidemiology of HIV/AIDS. Trop Med Int Health. 2000;5:A3–9.

Brabin BJ. Applied field research in malaria reports no 1 World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. 1991.

Brabin BJ, Agbaje SO, Ahmed Y, Briggs ND. A birthweight nomogram for Africa, as a malaria-control indicator. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1999;93 Suppl 1:S43–57.

Amegah AK, Damptey OK, Sarpong GA, Duah E, Vervoorn DJ, Jaakkola JJ. Malaria infection, poor nutrition and indoor air pollution mediate socioeconomic differences in adverse pregnancy outcomes in Cape Coast. Ghana PLoS One. 2013;8:e69181.

WHO. Guidelines on co-trimoxazole prophylaxis for HIV-related infections among children adolescents and adults. Recommendation for public health approach 2006. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006.

Klement E, Pitche P, Kendjo E, Singo A, D’Almeida S, Akouete F, et al. Effectiveness of co-trimoxazole to prevent Plasmodium falciparum malaria in HIV-positive pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa: an open-label, randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:651–9.

World Health Organization; UNAIDS. Provisional WHO/UNAIDS recommendations on the use of contrimoxazole prophylaxis in adults and children living with HIV/AIDS in Africa. Afr Health Sci. 2001;1:30–1.

van Eijk AM, Ayisi JG, ter Kuile FO, Otieno JA, Misore AO, Odondi JO, et al. Effectiveness of intermittent preventive treatment with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine for control of malaria in pregnancy in western Kenya: a hospital-based study. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:351–60.

WHO. Integrated management of pregnancy and childbirth. Pregnancy, childbirth and hostpartum care. A guide for essential practice. WHO: Geneva, Switzerland; 2006.

Klement E. Paludisme et infection par le VIH en Afrique subsaharienne = Malaria and HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa. La Lettre de l’infectiologue. 2008;23:42–9.

Manyando C, Njunju EM, D’Alessandro U, Van Geertruyden JP. Safety and efficacy of co-trimoxazole for treatment and prevention of Plasmodium falciparum malaria: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56916.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the immense contributions of students of Université Prostestante du Congo (UPC): Mpangi Mumvunga Sarah, Mpetshi Okar Margot, Muamba Matanda Marie Paul, Mujinga wa Mudumbi Tatiana and Mukandi Tshimpaka Carine.

This work was supported by the Institute of Parasitology, Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine of Kinshasa, Congo. The Protestant University of Congo (UPC) provided a grant for the first two years of study, but had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, or writing of the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

EK carried out the initial literature search, contributed to conception and design, completed the data analysis and interpretation of data, and drafted and edited the manuscript. RW and AN provided many of the condition definitions, contributed to the statistical analysis and interpretation of data, and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. KM, JZ, AK, MO, MNA and MNM revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Wumba, R.D., Zanga, J., Aloni, M.N. et al. Interactions between malaria and HIV infections in pregnant women: a first report of the magnitude, clinical and laboratory features, and predictive factors in Kinshasa, the Democratic Republic of Congo. Malar J 14, 82 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-015-0598-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-015-0598-2