Abstract

Background

In areas where malaria is endemic, pregnancy is associated with increased susceptibility to malaria. It is generally agreed that this risk ends with delivery and decreases with the number of pregnancies. Our study aimed to demonstrate relationships between malarial parasitaemia and age, gravidity and anaemia in pregnant women in Libreville, the capital city of Gabon.

Methods

Peripheral blood was collected from 311 primigravidae and women in their second pregnancy. Thick blood smears were checked, as were the results of haemoglobin electrophoresis. We also looked for the presence of anaemia, fever, and checked whether the volunteers had had chemoprophylaxis. The study was performed in Gabon where malaria transmission is intense and perennial.

Results

A total of 177 women (57%) had microscopic parasitaemia; 139 (64%)of them were primigravidae, 38 (40%) in their second pregnancy and 180 (64%) were teenagers. The parasites densities were also higher in primigravidae and teenagers. The prevalence of anaemia was 71% and was associated with microscopic Plasmodium falciparum parasitaemia: women with moderate or severe anaemia had higher parasite prevalences and densities. However, the sickle cell trait, fever and the use of chemoprophylaxis did not have a significant association with the presence of P. falciparum.

Conclusions

These results suggest that the prevalence of malaria and the prevalence of anaemia, whether associated with malaria or not, are higher in pregnant women in Gabon. Primigravidae and young pregnant women are the most susceptible to infection. It is, therefore, urgent to design an effective regimen of malaria prophylaxis for this high risk population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In areas where malaria is highly endemic, a protective semi-immunity against Plasmodium falciparum is acquired during the first 10–15 years of life, and the majority of malaria-related morbidity and mortality happens in young children [1]. However, in contrast with low malaria prevalence in adults, pregnant women in endemic areas are highly susceptible to malaria, and both the frequency and the severity of disease are higher in pregnant than non-pregnant women [2]. In pregnancy, there is a transient depression of cell-mediated immunity that allows foetal allograft retention but also interferes with resistance to various infectious diseases [3]. Cellular immune responses to P. falciparum antigens are depressed in pregnant women in comparison with non-pregnant control women [4, 5]. Anti-adhesion antibodies against chondroitin sulphate A-binding parasites are associated with protection from maternal malaria, but these antibodies develop only over successives pregnancies, accounting for the susceptibility of primigravidae to infection [6]. Indeed, women in first and second pregnancies are the most affected, with both gravidity and premunition influencing susceptibility to malaria infection [7–10]. Numerous epidemiological studies have reported a broad range of conditions during pregnancy which are a result of malaria [11–15]. As with peripheral parasitaemia, placental infection is also most frequent and heaviest in primigravidae [16]. Furthermore, malaria reduces birth-weight most in this group [16]. Although this data has been reported in many African countries, hardly anything is known about malaria in pregnant women from Gabon, a central African country where P. falciparum malaria is endemic. Thus, we conducted a community-based cross-sectional study to describe the prevalence of malaria parasitaemia and anaemia in pregnant women living in Libreville. As the prevalence of infection is lower in individuals with sickle cell trait compared with their normal haemoglobin counterparts [17], we also studied the frequency of the sickle cell trait.

Patients and methods

Study site and population

The study area is in Libreville, Gabon, where the climate is equatorial. Two rainy seasons occur in Gabon, from February to May and September to December, and two dry seasons. The annual temperature ranges from 24°C to 31°C (average 25.9°C), and the average humidity is greater than 80%. In this area, malaria is hyperendemic, predominantly caused by P. falciparum. The entomological inoculation rate (EIR), measured in an adjoining urban area, is 50 infected bites per person per year [18] and the main vectors are Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles funestus. This study was conducted during both the high rainy and dry seasons, from April 1995 to September 1996. Pregnant women (first and second pregnancy) attending the SMI de la Peyrie (a maternal and child health centre located in an urban area) were enrolled in the study.

Ethical considerations

All work was performed according to the guidelines for human experimentation in clinical research stated by the Ministry of Public Health and Population of Gabon. All women gave oral informed consent.

Data collection

Women in their first and second pregnancies were included in the study when they came for their first monthly antenatal visit. A number was attributed to each one, which was recorded on a prenatal consultation form. After a complete medical examination by nurse midwives and two physicians, the volunteer's age, weight, length of pregnancy, parity, exposure to antimalarial drug and axillary temperature were noted. Women were considered as having a fever when their temperature was ≥ 38°C. Gestational age was assessed using a gestational calendar, trimester was defined as first (<14 weeks), second (14–27 weeks) and third (>27 weeks). The biological check-up included measuring the haemoglobin rate (Hb), using haemoglobin electrophoresis to detect sickle cell trait and detecting parasitaemia.

Laboratory methods

Thick and thin blood films were stained with Giemsa and read for malaria parasites by two trained microscopists following standard, quality-controlled procedure [19]. Parasitaemia was expressed as the number of asexual forms of P. falciparum per microlitre: a result was considered negative after a reading of 1,000 leucocytes in the microscope (× 1,000). Haematological measurements were verified using a Coulter Hycel HC plus HD 21, an automated analyser. Parasitaemia was graded as low (1–999/μl), moderate (1000–9999/μl) and high (>10000/μl), haemoglobin levels as normal (>11 g/dl), low anaemia (11–9 g/dl), moderate anaemia (8.9–7 g/dl) and severe anaemia (<7 g/dl), and age as teenagers (<20 years old), young women (20–24 years old) and older women (>24 years old). P. falciparum-positive women were treated with quinine at 25 mg/kg/day during five days. The alkaline pH electrophoresis of haemoglobin was performed for sickle cell trait determination.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using EpiInfo 6.04b and the Statview software programme. For paired and unpaired comparisons of continuous variables, the non-parametric Wilcoxon sign rank, the Kruskal-Wallis, and Mann-Withney U-tests were used. Chi square analysis was used to compare proportions within and among groups. Adjusted tests were performed with the presence of malaria parasitaemia as a dependent variable using age and gravidity as possibly variables influencing malaria. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

-

311

women were selected at their first ACC (antenatal clinic care) at SMI de la Peyrie, patients' characteristics are summarised in Table I. 217 (70%) were primigravidae. The mean age was 19 years (13–37) with 93% less than 25 years. Primigravidae were significantly younger than secundigravidae (z = 3.20 p < 0.001). The mean length of pregnancy was four months (1–6). 17 (5%) women had started chemoprophylaxis with chloroquine (600 mg/week). 248 (80%) had a normal haemoglobin (AA), 56 (18%) had haemoglobin AS and seven (2%) had haemoglobin AC. There was no difference in distribution of these variables between primigravidae and women in their second pregnancy.

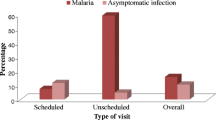

Malaria prevalence

Malaria prevalence was 57% (n = 177) (Table I). All infections were diagnosed as P. falciparum. The median of parasitaemia in all infected women was 930 parasites/microlitre (p/μl). Malaria prevalence was significantly higher in primigravidae women (64%) than in women in their second pregnancy (40%) (Odds ratio [OR] = 2.41, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.43 - 4.07, p < 0.001). Parasitaemic primigravidae women had higher median parasites density than parasitaemic secundigravidae (1050 versus 434 p/μL, z = 3.11, p = 0.002). (Table I). The prevalence of parasitaemia did not vary with season (dry or rainy). Overall, the parasite prevalence was 52% in the dry season and 59% in the rainy season (OR = 1.3, 95% IC = 0.77 - 2.30, p = 0.48)(data not shown).

Relation with age

Although pregnant women were young, and only in their first or second pregnancy, we compared the prevalence of P. falciparum infection between teenagers, young and older women. (Table II). Parasitaemia was significantly more common in teenagers (63.9%) than young (47.7%) and older women (55.5%) (χ2= 8.68, p = 0.013). No significant difference was found between younger and older women (OR = 1.09, 95% CI = 0.4 - 3.02, p = 0.85) (not shown). We separately examined teenagers (< 20 years old) and older (≥ 20 years old) women as well as primigravidae and secundigravidae for influences on malaria. Malaria prevalence was higher in teenagers than older women (64% versus 47%, OR = 1.99, 95% CI = 1.22 - 3.25, p = 0.002). After correcting for parity, this difference was also significant (OR = 1.77, 95% CI = 1.10 - 2.85, p < 0.01).

Relation with haemoglobin AS

Malaria prevalence was not influenced by the sickle cell trait. Although 64% of Hb AS women were infected compared to 55% Hb AA women, this difference was not statistically significant (OR = 1.4, 95% CI = 0.77 - 2.79), nor were the medians of parasitaemia.

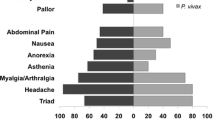

Relation with fever

In the groups recruited, 84 (27%) women had a fever. Within this group, 39 women (46%) had a plasmodial infection. The prevalence of plasmodial infection was significantly higher in women without fever (61%) (OR = 0.55, 95% CI = 0.33 - 0.95, p = 0.023). There was no difference in the medians of parasitaemia between these groups.

Relation with haemoglobin levels

Anaemia prevalence was 71% (n = 221) (Table I). In order to evaluate the effect of P. falciparum peripheral infections in women with and without anaemia, we compared the prevalence of parasitaemia. The presence of P. falciparum asexual form in peripheral blood was highly associated with anaemia. Indeed, anaemic women were significantly more infected (63%) than non-anaemic (41%) women (OR = 2.38, 95% CI = 1.4 - 4.05, p < 0.001). However, anaemia prevalence was similar between primigravidae and secundigravidae (Table I). There was no significant difference between teenagers, yound and older women (Table II). Mean haemoglobin level was 10.2 g/dl in all the enrolled women, and similar between women of different gravidity (Table I). Parasites grade and anaemia classes are cross-tabulated in Table III. Moderately and severely anaemic women had higher parasite densities (medians 2818 and 1166 p/μl) than women with low anaemia (981 p/μl). The lowest densities were observed in non-anaemic women. Association between sickle cell trait carriage and haemoglobin levels was assessed. The mean haemoglobin levels did not differ between Hb AS women and Hb AA women (10 versus 10.2 g/dl, z = -1.12, p = 0.26), nor were the prevalence of anaemia (71% versus 76.8%, OR = 1.08, 95% CI = 0.66 - 2.85, p = 0.37).

Relation with previous chloroquine chemoprophylaxis

Only 17 women (9 primigravidae and 8 secundigravidae) had taken chemoprophylaxis from the beginning of pregnancy. When we compared the levels of parasitaemia in this group to the other 294 women, we found that previous chloroquine prophylaxis had no effect on susceptibility to P. falciparum infection. The prevalence of infected women was not different: 47% in group with chemoprophylaxis had malaria compared to 57% of the women without previous chemoprophylaxis (OR = 1.19, 95% CI = 0.4 - 3.46, p = 0.73). The medians of parasitaemia were also similar (not shown).

Discussion

The susceptibility of pregnant women to malaria is well-established [1, 20]. However, no epidemiological data have been recorded in Libreville, the capital city of Gabon, where P. falciparum malaria is highly endemic. The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of malaria infection in Gabonese women who were pregnant and to determine the relationship between this and gravidity status, age, anaemia, the sickle cell trait and chemoprophylaxis.

We found that malaria prevalence was 57%. As expected, this prevalence was higher in primigravidae than secundigravidae, and in women under 20 years old. Anaemia prevalence was also higher, with a significant association between P. falciparum infection and anaemia. We also found that the presence of the sickle cell trait had no influence on malaria prevalence, nor did previous chemoprophylaxis. Likewise, age and gravidity had no effect on anaemia. These results are in agreement with those reported elsewhere, which show that P. falciparum infection is higher during pregnancy, more so in primigravidae and is usually associated with anaemia or reduced haemoglobin levels [21–27].

Our rationale for including pregnant women attending the SMI de la Peyrie is that they are representative of the general population in terms of accessibility to the health centers, and they had low income. In Gabon, early pregnancies are frequent, and 60% of population is below 25 years of age, the age of most of the pregnant women included in the study (93%). Women in their first and second pregnancies were chosen as they constitute one of the risk groups in stable malaria areas [20, 28–31].

Previous studies conducted in different areas in Gabon, have reported the prevalence of P. falciparum infection in pregnant women in the same range of our results. These studies were done at delivery [32, 33]. Only the study conducted by Garin et al. showed an increase of plasmodial parasitaemia during pregnancy in primigravidae and secundigravidae compared to multigravidae [34]. Our findings are in general accordance with findings from other areas (i.e. Malawi, Tanzania, Ghana, India), four urban sites with similar malaria epidemiological characteristics [21–24, 31]. In these vulnerable populations, primigravidae remain unquestionably the most susceptible: they are more often infected than multigravidae. In the same epidemiological context, these levels of prevalence are similar to those reported by other authors: 65% in Dielmo, Senegal [28], 62% in Tanzania [25], 65% in Malawi [26] and 41% in Kenya [35]. The levels of parasitaemia are also high in primigravidae. This could be explained by gravidity status, and as well as by the fact that the women were, in most cases, recruited at the fourth month of pregnancy. In the second trimester, parasitaemia is usually high compared to the first and the third trimester [24, 35]. Age and gravidity appeared to be the principal influences of malaria prevalence, mostly in teenagers.

Anaemia prevalence was also high in all women, i.e. 71%, in agreement with the mean percentage for Africa (61%) [36, 37]. This prevalence is identical to that reported in a group of pregnant women in Malawi [27] and Tanzania [24]. A significant role in the determination of anaemia has been demonstrated in this study. Women with low anaemia had the highest prevalence of malaria (50%), and higher parasite load was most common in women with severe anaemia. Similar finding were reported from Blantyre, Malawi [31]. In our study, gravidity and age did not influence the prevalence of anaemia and the mean heamoglobin levels. Therefore, all anaemia aetiologies in pregnant women should be further investigated.

Fever has not been found to be a good indicator of clinical malaria. Despite the fact that in endemic areas asymptomatic P. falciparum infections are frequent in adults, our study showed that malaria was not the main aetiology of fever during pregnancy. Other causes like urinary and genital infection could be the cause and should be treated to avoid subsequent obstetrical problems.

The prevalence of sickle cell trait in Gabon is about 22,5% [38]. Furthermore, the prevalence of infection has been reported to be lower in individuals with sickle cell trait compared to the normal-haemoglobin counterparts [17]. In our study population, the prevalence of the sickle cell trait was similar to the general population, and it did not influence the prevalence of malarial infection. This is not surprising: studies conducted by Van Dongen in Zambia and Mockenhaupt in Ghana have also shown that they no have no influence on each other [22, 39].

Previous chloroquine chemoprophylaxis has no effect on the prevalence of infection and parasitaemia. Chloroquine is still recommended as the first-line anti-malarial drug in preventive treatment for pregnant women in Gabon. It is widely used, affordable and available, thus, a reasonable choice for the majority of the population. Considering that the drug has been taken in correct doses, and that pregnant women generally use insecticides, is chloroquine still efficient in chemoprophylaxis since it is known that its efficacy in curative treatment in children and adults is less than 20% [40, 41]?

Unfortunately, we did not evaluate some confounding factors such as type of housing, stool hookworm burden or human immunodeficiency virus serostatus that seem to influence malaria and/or anaemia.

Conclusion

This study illustrates high prevalence of malaria and anaemia in pregnant women living in Libreville. Both are more common in first pregnancies, and primiparity and young age appear to be greater determinants of malaria risk. Chloroquine is still recommended by national health policy in Gabon, and chloroquine resistance in curative doses has been reported. Thus, an effective regimen of malaria prophylaxis of women during their first and second pregnancies is strongly recommended.

References

Riley EM, Hviid L, Theander TG: Malaria. In Parasitic Infections and the Immune System. Edited by: Kierszenbaum F. 1994, Academic Press, New York, 119-43.

Brabin B: An analysis of malaria in pregnancy in Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 1983, 61: 1005-16.

Meeusen EN, Bischof RJ, Lee CS: Comparative T-cell responses during pregnancy in large animals and humans. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2001, 46: 169-79.

Riley EM, Schneider G, Sambou I, Greenwood BM: Suppression of cell-mediated immune responses to malaria antigens in pregnant Gambian women. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989, 40: 141-4.

Fievet N, Cot M, Chougnet C, Maubert B, Bickii J, Dubois B, Lehesran JY, Frobert Y, Migot F, Romain F, Verhave JP, Louis F, Deloron P: Malaria and pregnancy in Cameroonian primigravidae-humoral and cellular immune responses to Plasmodium falciparum blood-stage antigens. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995, 53: 612-7.

Duffy PE, Fried M: Malaria during pregnancy: parasites, antibodies and chondroitin sulfate A. Biochem Soc Trans. 1999, 27: 478-82.

Bouvier P, Breslow N, Doumbo O: Seasonality malaria and impact of prophylaxis in an African village II. Effect on birth weight. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997, 56: 384-9.

Cot M, Breart G, Esveld M: Increase of birthweight following chloroquine chemoprophylaxis during pregnancy: results of a randomized trial in Cameroon. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995, 53: 581-85.

Deloron P, Maubert B: Interactions immunologiques entre paludisme et grossesse. Méd Trop. 1995, 55: 67S-68S.

Mutabingwa TK, Malle LN, Verhave JP: Malaria chemosuppression during pregnancy IV. Its effects on the newborn's passive malaria immunity. Trop Geog Med. 1993, 45: 150-6.

Salihu HM, Naik EG, Tchuinguem G: Weekly chloroquine prophylaxis and the effect on maternal haemoglobin status at delivery. Trop Med Int Health. 2002, 7: 29-34.

Mockenhaupt FP, Ulmen U, Von Gaertner C: Diagnosis of placental malaria. J Clin Microbiol. 2002, 40: 306-8.

Shulman CE, Marshall T, Dorman EK: Malaria in pregnancy: adverse effects on haemoglobin levels and birthweight in primigravidae and multigravidae. Trop Med Int Health. 2001, 6: 770-8.

Carles G, Bousquet F, Raynal P, Peneau C, Mignot V, Arbeile P: Pregnancy and malaria. Study of 143 cases in French Guyana. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 1998, 27: 798-805.

Greenwood AM, Armstrong JRM, Byass P, Snow RW, Greenwood BM: Malaria chemoprophylaxis, birth weight and child survival. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1992, 86: 483-5.

McGregor IA, Wilson ME, Billewicz WZ: Malaria infection of the placenta in The Gambia, West Africa: its incidence and relationship to still birth, birth weight and placental weight. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1983, 77: 232-44.

Ntoumi F, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Ossari S, Luty A, Reltien J, Georges A, Millet P: Plasmodium falciparum : sickle-cell trait is associated with higher prevalence of multiple infections in Gabonese children with asymptomatic infections. Exp Parasitol. 1997, 87: 39-46.

Sylla EH, Kun JF, Kremsner PG: Mosquito distribution and entomological inoculation rates in three malaria-endemic areas in Gabon. Trans R Trop Med Hyg. 2000, 94: 652-6.

Alonso PL, Smith T, Schellenberg JRM, Masanja H, Mwankusye S, Urassa H, Bastos de Azevedo I, Chongela I, Kobera S, Menendez C, et al : Randomised trial of efficacy of SPf66 vaccine against Plasmodium falciparum malaria in children in southern Tanzania. Lancet. 1994, 344: 1177-1181.

McGregor IA: Epidemiology, malaria and pregnancy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1984, 33: 517-525.

McDermott JM, Wirima JJ, Steketee RW, Steketee RW, Breman JG, Heyman DL: The effect of placental malaria infection on perinatal mortality in rural Malawi. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996, 55: 61-5.

Van Dongen PW, Van't Hof MA: Sickle cell trait malaria and anaemia in Zambian pregnant women. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1982, 16: 58-62.

Mockenhaupt FP, Rong B, Gunther M, Gunther M, Beck S, Till H, Kohn E, Thompson WN, Bienzle U: Anaemia in pregnant Ghanaian women:importance of malaria, iron deficiency and haemoglobinopathies. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000, 94: 477-83.

Nair LS, Nair AS: Effects of malaria infection on pregnancy. Indian J Malariol. 1993, 30: 207-14.

Wakibara JV, Mboera LE, Ndawi BT: Malaria in Mvumi, central Tanzania and the in vivo response of Plasmodium falciparum to chloroquine and sulphadoxine pyrimethamine. East Afr Med J. 1997, 74: 69-71.

Mattelli A, Donato F, Shein A, Much JA, Leopardi O, Astori L, Carosi G: Malaria and anaemia in pregnant women in urban Zanzibar, Tanzania. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1994, 88: 475-83.

Van Den Broek NR, Rogerson SJ, Mhango CG, Kambala B, White SA, Molyneux ME: Anaemia in pregnancy in Southern Malawi: prevalence and risk factors. BJOG. 2000, 107: 445-451.

Diagne N, Cisse B, Rogier C, Trape JF: Incidence of clinical malaria in pregnant women exposed to intense perennial transmission. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997, 91: 166-70.

Cot M, Abel L, Roisin A, Barro D, Yada A, Carnevale P, Feingold J: Risk factors of malaria infection during pregnancy in Burkina Faso: suggestion of a genetic influence. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993, 48: 358-64.

Mutabingwa TK, Malle LN, De Geus A, Oosting J: Malaria chemosuppression in pregnancy I. The effect of chemosuppressive drugs on maternal parasitaemia. Trop Geogr Med. 1993, 45: 6-14.

Rogerson SJ, Van den Broek NR, Chaluluka E, Qongwane C, Mhango CG, Molyneux ME: Malaria and anemia in antenatal women in Blantyre, Malawi: a twelve-month survey. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000, 62: 335-40.

Walter PR, Garin YJ, Blot P: Placental pathologic changes in malaria. Histologic and ultrastructural study. Am J Pathol. 1982, 109: 330-42.

Zinsou RD, Engongah-Beka T, Richard-Lenoble D, Philippe E, Awassi A, Kombila M: Malaria and pregnancy. Comparative study of Central Africa and Western Africa. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 1987, 16: 485-8.

Garin YJ, Blot P, Walter P, Pinon JM, Vernes A: Malarial infection of the placenta. Parasitologic, clinical and immunologic aspects. Arch Fr Pediatr. Suppl 2: 917-20.

Shulman CE, Dorman EK, Cutts F, Kawuondo K, Bulmer JN, Peshu N, Marsh K: Intermittent sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine to prevent severe anaemia secondary to malaria in pregnancy: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 1999, 353: 632-6.

World Health Organization: Le dossier mère-enfant: Anémie et grossesse. WHO/FHE/MSM 94–11 Rev 1. 1994

World Health Organisation: Grossesse et paludisme. WHO/MAL/94. 1070

Richard-Lenoble D, Toublanc JE, Zinsou RD, Kombila M, Carme E: Result of a systematic study of drepanocytosis in 1,500 Gabonese using hemoglobin electrophoresis. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1980, 73: 200-6.

Mockenhaupt FP, Rong B, Till H, Eggelte TA, Beck S, Gyasi-Sarpo C, Thomson WN, Bienzle U: Submicroscopic Plasmodium falciparum infections in pregnancy in Ghana. Trop Med Int Health. 2000, 5: 167-73.

Kremsner PG, Wilding E, Jenne L, Brandts C, Neifer S, Bienzle U, Graninger N: Comparison of micronized halofantrine with Plasmodum falciparum malara in adults from Gabon. Am J Trop med Hyg. 1994, 50: 790-75.

Pradines B, Mabika Manfoumbi M, Parzy D, Owono Medang M, Lebeau C, Mourou Mbina JR, Doury JC, Kombila M: In vitro susceptibility of Gabonese wild isolates of Plasmodium falciparum to artemether, and comparison with chloroquine, quinine, halofantrine and amodiaquine. Parasitology. 1998, 117: 541-5.

Acknowledgements

This study is part of the doctoral thesis of Marielle K. Bouyou-Akotet. The contribution of the volunteers and the staff of SMI of la Peyrie, Libreville, Gabon is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Dr Vincent Guiyedi for his advice.

Source of support: This study received financial support from the WHO: Programme de lutte contre le Paludisme, contract number AF/ICP/CTD/063/VD.94 and from the AUPELF-UREF Programme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors'contributions

MK B-A participated in study and in the statistical analysis and the drafting of the manuscript. DE I-C participated in the design of the study and the statistical analysis. M M. carried out the study and participated in biological tests. E K participated in the statistical analysis. PB M participated in the medical and biological tests. E M participated in the design of the study and the drafting of the manuscript. M K coordinated and participated in the design of the study, statistical analysis, and the drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Bouyou-Akotet, M.K., Ionete-Collard, D.E., Mabika-Manfoumbi, M. et al. Prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum infection in pregnant women in Gabon. Malar J 2, 18 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-2-18

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-2-18