Abstract

Background

Increasing evidence suggest that statin therapy has a diabetogenic effect. Individual types of statin may have a different effect on glucose metabolism. Using the repeated nationwide population-based health screening data in Korea, we investigated the longitudinal changes in fasting glucose level of non-diabetic individuals by use of statins.

Methods

From the National Health Screening Cohort, we included 379,865 non-diabetic individuals who had ≥ 2 health screening examinations with fasting blood glucose level measured in 2002–2013. Using the prescription records of statins in the database, we calculated the proportion of days covered (PDC) and average number of defined daily doses per day (anDDD) by statins. We constructed multivariate linear mixed models to evaluate the effects of statins on the changes in fasting glucose (Δglu).

Results

High PDC by statins had a significant positive effect on Δglu (coefficient for PDC 0.093 mmol/L, standard error 0.007, p < 0.001). anDDD by statins was also positively associated with Δglu (coefficient for anDDD 0.119 mmol/L, standard error 0.009, p < 0.001). Unlike statins, the PDC by fibrate and ezetimibe were not significantly associated with Δglu. There was no significant interaction effect on Δglu between time interval and statin. Considering individual types of statins, use of atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, pitavastatin, and simvastatin were significantly associated with increase of Δglu. Pravastatin, lovastatin, and fluvastatin were also positively associated with Δglu, but were not statistically significant.

Conclusions

More adherent and intensive use of statins was significantly associated with an increase in fasting glucose of non-diabetic individuals. In subgroup analysis of individual statins, use of atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, pitavastatin and simvastatin had significant association with increase in fasting glucose. Pravastatin, lovastatin, and fluvastatin had non-significant trend toward an increased fasting glucose. Our findings suggest the medication class effect of statins inducing hyperglycemia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Statins, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme reductase (HMGCR) inhibitors, are class of lipid lowering medications with pleiotropic properties due to anti-inflammatory, anti-thrombotic, and anti-oxidative effects [1]. It is well-established that statins can reduce the risk for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases [2]. In clinical practice, statins have a major role in the prevention of cardiovascular disease for those at higher risk. Besides the cardiovascular benefits, there are concerns that statins may lead to hyperglycemia and increase the risk of new-onset diabetes mellitus (DM) [3,4,5]. In randomized and observational studies, there was a higher incidence of new-onset DM in patients receiving statin compared to those who were not [4]. As DM is a major risk factor of cardiovascular disease and various long-term complications, this is a clinically important issue. But also DM, impaired fasting glucose and pre-diabetes are significant cardiovascular risk factor [6,7,8]. Experimental and clinical data suggested that statins may lead to the increase of insulin-resistance and hyperglycemia [9, 10]. However, there are still insufficient data for the longitudinal changes in fasting glucose with the use of statins. In addition, there are multiple types of statin, each with a different chemical structure and pharmacokinetic profile [11, 12]. The individual statin types may have different effects on glucose metabolism [13, 14]. To investigate these issues, we conducted a longitudinal study to analyze the changes in fasting glucose by use of statins based on data from repeatedly performed nationwide health examinations in Korea.

Methods

Data source

This study was based on the National Health Insurance Service-National Health Screening Cohort (NHIS-HEALS) in Korea [15]. The NHIS offers a free health examination program to all members ≥ 40 years old every 2 years. Among the Korean subjects aged 40–79 who underwent the health examination during 2002–2003, about 10% (n = 541,866) were randomly selected to form the NHIS-HEALS. NHIS-HEALS contained serial health examination data including fasting glucose, blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), questionnaire for lifestyle, and every individual’s health insurance claim data for hospital visits, medical procedures, diagnoses (based on International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision, ICD-10), and drug prescriptions during the study period of 2002–2013. All included subjects were followed-up until death, loss of eligibility for NHIS due to emigration, or Dec 31, 2013, which is the end of the study period.

Study subjects

To investigate the longitudinal change in fasting glucose, we selected subjects who had data on their fasting glucose level from at least 2 health examinations during the study period of 2002–2013. For each subject, the baseline value of fasting glucose was defined as the value at the first health examination. As the use of anti-diabetic medication can influence the fasting glucose level, we only included non-diabetic individuals. Therefore, we excluded patients who (1) had a fasting glucose level ≥ 7 mmol/L at the baseline health examination, (2) answered “yes” to the diagnosis of DM on the questionnaire in health examination, (3) had a diagnosis of DM (ICD-10 code ‘E10–E15’) from the health insurance claim data, and (4) had received a prescription for anti-diabetic medication during the study period.

Data collection

In the serial NHIS health examinations, data were collected for sex, age, BMI, household income, and systolic blood pressure. At each examination, fasting glucose was measured with a venous blood sample after more than 6 h of fasting. The questionnaire for lifestyle in the health examination contained questions regarding smoking status, alcohol consumption, and physical activity [15]. Alcohol consumption was classified into ‘less than 1 time’, ‘1–2 times’, ‘3–4 times’, and ‘≥ 5 times’ according to the how many times alcohol was consumed per week on average. Physical activity was grouped into ‘< 1 day’, ‘1–4 days’, and ‘≥ 5 days’ according to the number of days of exercise per week on average (regardless of type or duration of exercise). Health examination data with missing values for any of fasting glucose or covariates (sex, age, BMI, household income, systolic blood pressure, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and physical activity) were excluded from the analysis. Health examination data with extreme values of fasting glucose (≤ 3 or ≥ 25 mmol/L) were also excluded [16]. If the initial health examination data in each patient was excluded due to incomplete data for fasting glucose or covariates, the next health examination was treated as baseline data for the patient.

Statistical analysis with data for medications

As fasting glucose was measured repeatedly, we constructed a linear mixed-effect model to analyze the change in fasting glucose (Δglu = gluexam − glubase, mmol/L) over time. In the linear mixed-effect model, variables of fixed effects were sex, age, fasting glucose level at baseline (initial measurement), time interval (Δtime; time between baseline and serial measurements), use of statins during the time interval, and other clinical characteristics obtained from the serial NHIS health examinations (systolic blood pressure, BMI, household income, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and physical activity). The general structure for the mixed model was Δglu = β*time + β*statin + β*other covariates + intercept (where β is a regression coefficient for the variable). To evaluate the effect of statins on the change in fasting glucose, we calculated the β of statins in the linear mixed model. As markers of statin use during the period between baseline and serial measurements, we calculated 1) proportion of days covered (PDC) = ‘number of days covered by statins divided by total number of days’ and 2) average number of defined daily doses per day (anDDD) = ‘cumulative doses of statins during the period divided by total number of days and defined daily dose of each statin’. Defined daily doses (DDD) of each statin were 20 mg for atorvastatin, 10 mg for rosuvastatin, 2 mg for pitavastatin, 30 mg for pravastatin, 30 mg for simvastatin, 45 mg for lovastatin, and 60 mg for fluvastatin according to the World Health Organization. If a subject received 40 mg of atorvastatin for 180 days during a period of 760 days between the baseline and next NHIS health examination, PDC by statins over the period would be 180/760 = 0.25 and anDDD by statins would be 40*180/20/760 = 0.5. If a subject received 20 mg of atorvastatin for 60 days followed by 10 mg of rosuvastatin for 120 days during a period of 360 days between the baseline and next NHIS health examination, PDC by statins would be (60 + 120)/360 = 0.5 (PDC by atorvastatin would be 0.166 and PDC by rosuvastatin would be 0.333) and anDDD by statins would be (20*60/20 + 10*120/10)/360 = 0.570. In this case, anDDD by atorvastatin would be 20*60/20/360 = 0.237 and anDDD by rosuvastatin would be 10*120/10/360 = 0.333. To evaluate the effects of non-statin lipid-lowering medications on glucose, we also calculated data of PDC by fibrate (bezafibrate, ciprofibrate, etofibrate, fenofibrate, and gemfibrozil) and ezetimibe during the study period in the same manner. The data management and statistical analyses were performed with the SAS statistical software package, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and R software, version 3.4.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; http://www.R-project.org/). A two-sided p < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Subjects

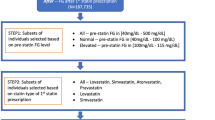

According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we finally included 379,865 non-diabetic subjects who received ≥ 2 measurements of fasting glucose level (Fig. 1). The mean age at the baseline NHIS health examination was 51.9 ± 9.2 years and males comprised 52.6% of the subjects. During the study period, the median number of glucose measurements per subject was 5 (interquartile range, 4–6). The clinical characteristics of the included subjects are summarized in Table 1. Among the included subjects, the prevalence of exposure to statins (at least 1 prescription of statins during the study period) was 25.3% (Table 2). The total cumulative duration of exposure to any statins were 165,083 years. The proportion of patients who were exposed to fibrate and ezetimibe were 3.9% and 1.5%, respectively.

Factors associated with the change in fasting glucose

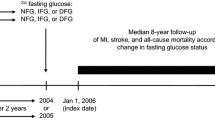

In the multivariate linear mixed model for the change in fasting glucose (Δglu), being male, older age, lower fasting glucose level at baseline, higher systolic blood pressure, higher BMI, being a current smoker, lower household income, higher alcohol consumption, and less exercise were positively associated with Δglu (Table 3). High PDC by statins had a significant positive effect on Δglu (coefficient for PDC 0.093 mmol/L, standard error 0.007, p < 0.001), which indicates that adherent use of statins was associated with an increase in fasting glucose. Unlike statins, PDC by fibrate (coefficient for PDC 0.022 mmol/L, standard error 0.025, p = 0.387) and ezetimibe (coefficient for PDC 0.046 mmol/L, standard error 0.045, p = 0.314) were not significantly associated with Δglu. When we performed analysis including anDDD in place of PDC as a marker of statin intensity, anDDD by statins was also positively associated with Δglu (coefficient for anDDD 0.119 mmol/L, standard error 0.009, p < 0.001). These findings suggested that more adherent and intensive statin therapy could cause an increase in fasting glucose. We plotted the estimated change in Δglu according to statin therapy in the linear mixed models including the interaction term between time and statin therapy (Fig. 2). In the plots, Δglu increased in proportion to PDC and anDDD without the lines crossing over time indicating that there was no interaction effect between time interval and statin therapy.

Effects of statin therapy on the change in fasting glucose over time. Plots illustrate the estimated change in fasting glucose (line) and 95% confidence interval (shadow) based on the multivariate linear mixed models adjusted for the variables listed in Table 3. a According to adherent use of statin therapy (PDC). b According to intensity of statin therapy (anDDD). PDC, proportion of days covered by statins for the time period between baseline and serial measurements of fasting glucose; anDDD, average number of defined daily doses per day for the time period between baseline and serial measurements of fasting glucose

Effect of each statin type on the change in fasting glucose

To investigate the effect of each statin type on fasting glucose, we reconstructed the linear mixed model to include PDC for each type of statin. Figure 3 shows the coefficient of PDC for each statin for Δglu. PDC of atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, pitavastatin, and simvastatin had significant positive effects on Δglu. PDC of pravastatin, lovastatin, and fluvastatin also had positive effects on Δglu, but were not statistically significant. When we included anDDD of each statin instead of PDC, there was a similar finding; anDDD by atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, pitavastatin, and simvastatin had significant positive effects on Δglu, but anDDD by pravastatin, lovastatin, and fluvastatin had non-significant positive effects. No statin type had significant interaction effect with time interval in the linear mixed models.

Effects of individual statins on the change in fasting glucose. Data are coefficients (β) and 95% CIs of individual statins on the change in fasting glucose derived by the multivariate linear-mixed models adjusted for the variables listed in Table 3. PDC, proportion of days covered by statins for the period between baseline and serial measurements of fasting glucose; anDDD, average number of defined daily doses per day; CI confidence interval

Discussion

In this longitudinal study using the repeated measurements of fasting glucose level in nationwide health examinations, there was a statistically significant association between statin therapy and increase in fasting glucose in non-diabetic individuals (more adherent and intensive statin users had higher fasting glucose). Non-statin lipid lowering medications of fibrate and ezetimibe were not associated with change in fasting glucose. When we analyzed individual statin types, all types of statins were positively associated with an increase in fasting glucose although the effects of pravastatin, lovastatin, and fluvastatin were not significant. Our findings are in line with the current consensus that statin can induce insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and new-onset DM [17, 18]. However, our study should not be interpreted as to merely avoid statins due to the hyperglycemic effect. Overall evidence show that the benefits of statins far outweigh the potential hazards [19,20,21]. Statin therapy was associated with less good glycemic control in diabetes and pre-diabetes, but there was a much lower risk of major cardiovascular events [22, 23]. Real-world studies consistently indicate that statins are frequently suboptimal and under prescribed in populations with high cardiovascular risk [24,25,26,27].

When we plotted estimated change in fasting glucose over time (Fig. 2), more adherent and intensive use of statins had positive effects on the change in fasting glucose level, but there was no significant interaction between statins and time interval. That means that use of statins may induce an increase in fasting glucose, but the slope of increase in fasting glucose over time was not associated with the statin therapy. Therefore, we supposed that there is no reason to avoid statins for high risk cardiovascular patients due to the concern for additional hyperglycemia over time induced by long-term statin therapy. This finding was consistent with a prior meta-analysis evaluating the change in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) by statins in DM patients; there was no significant interaction between the duration of statin treatment and increase of HbA1c [28]. In addition, we found that the increase in fasting glucose was influenced by an unhealthy lifestyle of smoking, higher alcohol consumption, and lower physical activity. Higher systolic blood pressure, higher BMI, and lower household income were also associated with increase in fasting glucose. These findings support the current recommendations highlighting the importance of lifestyle modifications to prevent impaired glucose tolerance and DM [29].

With expanded indications for statin in the recent guidelines, statins have become the first-line therapy for cardiovascular protection [30]. As more patients take statins, there is awareness of unwanted side effects as well as benefits of statins [31]. Due to there are pathophysiologic and epidemiologic data for a linkage between hyperglycemia and increased cardiovascular or all-cause mortality in diabetic and non-diabetic patients, physicians should be cautious about the potential risk of statin-mediated hyperglycemia and new-onset DM [32, 33]. To maintain the cardiovascular benefit and minimalize the potentially adverse hyperglycemic effect with statins, multi-strategy approach should be considered, including monitoring of fasting glucose, control of predisposing factors to glucose intolerance and unhealthy life-style, proper selection of the statin (type and dosage) and concomitant medications [21, 34]. Screening and risk stratification for diabetes on the initiation of statins and periodical monitoring of fasting glucose would be helpful for early diagnosis and proper glucose control in patients on statin therapy [33, 35]. Sustainable lifestyle changes can improve control of both glucose metabolism and cardiovascular risk [36]. Encouraging healthy dietary pattern, physical activity, body weight control, and quitting smoking could be effective to prevent impaired glucose tolerance and DM [29, 37]. There are a number of medications with diabetogenic property such as thiazide diuretics and steroids; concomitant use of the medications may further increase the risk of impaired glucose metabolism and DM [38, 39].

To explain the diabetogenic effect of statins, numerous mechanisms have been proposed. Glucose and lipid metabolism are interconnected in many ways [40]. Gene variants involved in lipid metabolism (Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1, Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9, and HMGCR) are significantly associated with obesity, hyperglycemia and DM [41,42,43]. Lower prevalence of type 2 DM in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia suggests genetic links between glucose and lipid metabolism [44]. Statins-induced cholesterol-dependent conformational changes in glucose transporter (GLUT) proteins can lead to impaired glucose uptake in the cells and insulin resistance [45]. Inhibition of de-novo cholesterol synthesis by statins results in deleterious inflammation and oxidation within islet β-cells, which lead to cellular apoptosis and impaired insulin secretion [46]. Biosynthesis of the isoprenoid side chain of coenzyme Q10 is suppressed by statins, which has been implicated in the downregulation of GLUT4 synthesis, mitochondrial oxidative stress, delayed adenosine triphosphate production, and apoptosis of β-cells, causing impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion [19, 47, 48]. Simvastatin and atorvastatin have been shown to reduce the level of adiponectin, which is a hormone with anti-inflammatory and anti-diabetogenic properties secreted by adipocytes [19, 49]. One of the most common complaints with statins is muscle-related symptoms (muscle pain, myopathy, myalgia, and fatigue) [50]. Statin-related muscle complaints are frequently exacerbated by exercise, which further limits physical activity and exercise performance [51]. Since physical inactivity is associated with abdominal adiposity, body weight gain, and glucose intolerance, limited physical activity by statins may be a mediator of glucose intolerance [23, 52, 53].

There are scarce data on the effects of individual statins on DM and diabetogenic potency. Previous meta-analyses with randomized and observational studies have shown no clear difference between statin types in terms of DM incidence [5, 54]. The Women’s Health Initiative showed that an increased risk of DM was observed for all types of statins [55]. Therefore, all statins seem to have a diabetogenic potency considered as a medication class effect [17]. However, individual statins have different mechanisms of action and pharmacokinetic properties, and experimental data suggest that different statins have varying effects on glucose metabolism [56]. Based on available clinical and experimental data, it is generally accepted that atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, simvastatin, lovastatin, and fluvastatin have an unfavorable influence on glycemic parameters and risk of new-onset DM [57].

Some data suggested that pravastatin may have relatively weak diabetogenicity compared to that of other statins [3]. In a network meta-analysis, pravastatin had the lowest risk of inducing new-onset DM among the high-dose statin therapy (atorvastatin 80 mg, rosuvastatin 20 mg, simvastatin 40 mg, and pravastatin 40 mg), but the difference was not statistically significant [58]. The West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study showed that pravastatin therapy resulted in a 30% reduction in the risk of new-onset DM compared to placebo [59]. The relatively lower risk of DM with pravastatin was also reported in retrospective studies using the real-world data [60, 61]. Unlike other statins, pravastatin may increase plasma adiponectin levels and improve insulin sensitivity mediated by the elevation of calcitriol [62]. The hydrophilicity of pravastatin may have little effect on membrane-embedded proteins involving glucose metabolism such as the GLUT [63]. However, the Prospective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk (PROSPER) trial showed that the risk of new-onset diabetes increased by 30% in patients treated with pravastatin compared with those given a placebo [64].

Pitavastatin is the newest statin and has been shown to be well-tolerated with fewer side effects and a relatively low drug interaction profile [65]. A recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials with pitavastatin suggested that pitavastatin did not adversely affect glucose metabolism or increase risk of developing diabetes compared to the controls [66]. In the Japan Prevention Trial of Diabetes by Pitavastatin in Patients With Impaired Glucose Tolerance (J-PREDICT) trial, treatment with pitavastatin reduced the risk of new‐onset DM by 18% in patients with impaired glucose tolerance [67]. The Japanese long-term prospective post-marketing surveillance LIVALO Effectiveness and Safety (LIVES) study demonstrated that treatment with pitavastatin lowered HbA1c (from 8.1% at baseline to 7.4% at 6 months) in the patients with poorly controlled diabetes [68].

In our study, all classes of statins were associated with an increase in fasting glucose although the effects of pravastatin, lovastatin, and fluvastatin were not significant. In our data, the hyperglycemic effects of pitavastatin does not seem to be lower than that of other statins in contrast to the favorable reports for pitavastatin on glucose metabolism. A recent retrospective cohort study in Korea also reported that pitavastatin had the highest risk of new-onset DM compared to other statins [69].

In a number of prior studies, there are inconsistent findings about the diabetogenic property of individual statins. The discrepancy could be originated from difference in baseline characteristics of study population, coexisting risk factors, follow-up duration, medication adherence and so on. It is known that statin-induced DM risk is higher in pre-diabetes and patients with predisposing factors for DM such as old age and obesity [34]. The short-term and long-term effects on glucose metabolism may be different in accordance with type of statins and underlying characteristics of patients [70]. The diabetogenic effect of statins may be varied in genetic background [71]. In patients who were prescribed statins, discontinuation and poor adherence were common in clinical practice, which limits assessing the diabetogenic effect of statins [72]. The effect of statins on glucose metabolism are complex and interconnected by multiple pathways; individual statins may have a heterogenous impact on the multiple processes [11]. To obtain further knowledge of individual statins on glucose metabolism, there is need for further extensive studies.

This study had both strengths and limitations. From a population-based nationwide health screening program, we collected data from a large cohort of 379,865 patients over a 10-year study period. Serial data of more than 2,000,000 measurements of fasting glucose were analyzed. Besides data on fasting glucose, we also included detailed data on blood pressure, BMI, and lifestyle. The significant effects of an unhealthy lifestyle on fasting glucose including smoking, higher alcohol intake, higher BMI and lower physical activity may support the relevance of this study. In Korea, statins must be prescribed by physicians and refill programs at pharmacies are not allowed. Using the health insurance claim data, prescription records for individual statin could be accessed. However, the actual intake of statins in subjects might be different from the prescription records. Fortunately, there was good correlation between prescription and real exposure to drugs in prior studies [73, 74]. Our study was retrospectively performed and due to the observational nature, there was a possibility of hidden bias due to uncollected data. We excluded a large proportion of subjects with DM or who had received anti-diabetic medication during the study period to eliminate the potential bias caused by the effects of this medication on glucose level. The item for physical activity lacked data for the type and duration of exercise. This study was based on Koreans; the response to statins might be varied in other genetic population. Therefore, our results should be interpreted with caution and further studies are needed to confirm these findings in other populations.

Conclusions

There was significant increase of fasting glucose in non-diabetic individuals in proportion to adherent and intensive use of statins. Among the statin subtypes, use of atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, pitavastatin and simvastatin were associated with significant increase in fasting glucose. Pravastatin, lovastatin, and fluvastatin also had trend toward an increased fasting glucose, but were statistically non-significant. These finding suggested medication class effect of all types of statins predisposing hyperglycemia although there was some difference in the degree according to the type. We need to find optimal strategy to maximize the cardiovascular benefit and minimalize the hyperglycemic effect by statins.

Abbreviations

- anDDD:

-

average number of defined daily doses per day

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- DDD:

-

defined daily doses

- DM:

-

diabetes mellitus

- GLUT:

-

glucose transporter

- HbA1c:

-

hemoglobin A1c

- HMGCR:

-

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase

- ICD-10:

-

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision

- NHIS:

-

National Health Insurance Service

- NHIS-HEALS:

-

National Health Insurance Service-National Health Screening Cohort

- PDC:

-

proportion of days covered

- Δglu:

-

changes in fasting glucose

References

Pedersen TR. Pleiotropic effects of statins: evidence against benefits beyond LDL-cholesterol lowering. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2010;10(Suppl 1):10–7.

Taylor F, Huffman MD, Macedo AF, Moore THM, Burke M, Davey Smith G, et al. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;1:CD004816.

Sattar N, Preiss D, Murray HM, Welsh P, Buckley BM, de Craen AJM, et al. Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomised statin trials. Lancet. 2010;375:735–42.

Ridker PM, Pradhan A, MacFadyen JG, Libby P, Glynn RJ. Cardiovascular benefits and diabetes risks of statin therapy in primary prevention: an analysis from the JUPITER trial. Lancet. 2012;380:565–71.

Casula M, Mozzanica F, Scotti L, Tragni E, Pirillo A, Corrao G, et al. Statin use and risk of new-onset diabetes: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;27:396–406.

Huang Y, Cai X, Mai W, Li M, Hu Y. Association between prediabetes and risk of cardiovascular disease and all cause mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2016;355:i5953.

Ford ES, Zhao G, Li C. Pre-diabetes and the risk for cardiovascular disease: a systematic review of the evidence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1310–7.

Biteker M, Dayan A, Can MM, İlhan E, Biteker FS, Tekkeşin A, et al. Impaired fasting glucose is associated with increased perioperative cardiovascular event rates in patients undergoing major non-cardiothoracic surgery. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2011;10:63.

Anyanwagu U, Idris I, Donnelly R. Drug-induced diabetes mellitus: evidence for statins and other drugs affecting glucose metabolism. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;99:390–400.

Puurunen J, Piltonen T, Puukka K, Ruokonen A, Savolainen MJ, Bloigu R, et al. Statin therapy worsens insulin sensitivity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:4798–807.

Lin L-Y, Huang C-C, Chen J-S, Wu T-C, Leu H-B, Huang P-H, et al. Effects of pitavastatin versus atorvastatin on the peripheral endothelial progenitor cells and vascular endothelial growth factor in high-risk patients: a pilot prospective, double-blind, randomized study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014;13:111.

Ginsberg H. Statins in cardiometabolic disease: what makes pitavastatin different? Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2013;12(Suppl 1):S1.

Zhao W, Zhao S-P. Different effects of statins on induction of diabetes mellitus: an experimental study. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2015;9:6211–23.

Millán Núñez-Cortés J, Cases Amenós A, Ascaso Gimilio JF, Barrios Alonso V, Pascual Fuster V, Pedro-Botet Montoya JC, et al. Consensus on the statin of choice in patients with impaired glucose metabolism: results of the DIANA Study. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2017;17:135–42.

Seong SC, Kim Y-Y, Park SK, Khang YH, Kim HC, Park JH, et al. Cohort profile: the National Health Insurance Service-National Health Screening Cohort (NHIS-HEALS) in Korea. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e016640.

Tabák AG, Jokela M, Akbaraly TN, Brunner EJ, Kivimäki M, Witte DR. Trajectories of glycaemia, insulin sensitivity, and insulin secretion before diagnosis of type 2 diabetes: an analysis from the Whitehall II study. Lancet. 2009;373:2215–21.

Chogtu B, Magazine R, Bairy K. Statin use and risk of diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes. 2015;6:352–7.

Liew SM, Lee PY, Hanafi NS, Ng CJ, Wong SSL, Chia YC, et al. Statins use is associated with poorer glycaemic control in a cohort of hypertensive patients with diabetes and without diabetes. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2014;6:53.

Chan DC, Pang J, Watts GF. Pathogenesis and management of the diabetogenic effect of statins: a role for adiponectin and coenzyme Q10? Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2015;17:472.

Goldfine AB. Statins: is it really time to reassess benefits and risks? N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1752–5.

Ray K. Statin diabetogenicity: guidance for clinicians. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2013;12(Suppl 1):S3.

Anyanwagu U, Mamza J, Donnelly R, Idris I. Effects of background statin therapy on glycemic response and cardiovascular events following initiation of insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes: a large UK cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16:107.

Kei A, Rizos EC, Elisaf M. Statin use in prediabetic patients: rationale and results to date. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2015;6:246–51.

Berthold HK, Gouni-Berthold I, Böhm M, Krone W, Bestehorn KP. Patterns and predictors of statin prescription in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2009;8:25.

Bai JW, Boulet G, Halpern EM, Lovblom LE, Eldelekli D, Keenan HA, et al. Cardiovascular disease guideline adherence and self-reported statin use in longstanding type 1 diabetes: results from the Canadian study of longevity in diabetes cohort. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15:14.

Hanefeld M, Traylor L, Gao L, Landgraf W. The use of lipid-lowering therapy and effects of antihyperglycemic therapy on lipids in subjects with type 2 diabetes with or without cardiovascular disease: a pooled analysis of data from eleven randomized trials with insulin glargine 100 U/mL. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16:66.

Toth PP, Zarotsky V, Sullivan JM, Laitinen D. Dyslipidemia treatment of patients with diabetes mellitus in a US managed care plan: a retrospective database analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2009;8:26.

Erqou S, Lee CC, Adler AI. Statins and glycaemic control in individuals with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2014;57:2444–52.

Summary of Revisions. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:S4–6.

Mortensen MB, Nordestgaard BG. Comparison of five major guidelines for statin use in primary prevention in a contemporary general population. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168:85–92.

Golomb BA, Evans MA. Statin adverse effects: a review of the literature and evidence for a mitochondrial mechanism. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2008;8:373–418.

Pistrosch F, Natali A, Hanefeld M. Is hyperglycemia a cardiovascular risk factor? Diabetes Care. 2011;34:S128–31.

Sattar NA, Ginsberg H, Ray K, Chapman MJ, Arca M, Averna M, et al. The use of statins in people at risk of developing diabetes mellitus: evidence and guidance for clinical practice. Atheroscler Suppl. 2014;15:1–15.

Bernardi A, Rocha VZ, Faria-Neto JR. Use of statins and the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 1992;2015(61):375–80.

Maki KC, Ridker PM, Brown WV, Grundy SM, Sattar N. The Diabetes Subpanel of the National Lipid Association Expert Panel null. An assessment by the Statin Diabetes Safety Task Force 2014 update. J Clin Lipidol. 2014;8:S17–29.

Swerdlow DI, Sattar N. A dysglycaemic effect of statins in diabetes: relevance to clinical practice? Diabetologia. 2014;57:2433–5.

Thomas GN, Jiang CQ, Taheri S, Xiao ZH, Tomlinson B, Cheung BMY, et al. A systematic review of lifestyle modification and glucose intolerance in the prevention of type 2 diabetes. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2010;6:378–87.

Shen L, Shah BR, Reyes EM, Thomas L, Wojdyla D, Diem P, et al. Role of diuretics, β blockers, and statins in increasing the risk of diabetes in patients with impaired glucose tolerance: reanalysis of data from the NAVIGATOR study. BMJ. 2013;347:f6745.

Fathallah N, Slim R, Larif S, Hmouda H, Ben Salem C. Drug-induced hyperglycaemia and diabetes. Drug Saf. 2015;38:1153–68.

Parhofer KG. Interaction between glucose and lipid metabolism: more than diabetic dyslipidemia. Diabetes Metab J. 2015;39:353–62.

Ference BA, Robinson JG, Brook RD, Catapano AL, Chapman MJ, Neff DR, et al. Variation in PCSK9 and HMGCR and risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2144–53.

Schmidt AF, Swerdlow DI, Holmes MV, Patel RS, Fairhurst-Hunter Z, Lyall DM, et al. PCSK9 genetic variants and risk of type 2 diabetes: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:97–105.

Lotta LA, Sharp SJ, Burgess S, Perry JRB, Stewart ID, Willems SM, et al. Association between low-density lipoprotein cholesterol-lowering genetic variants and risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316:1383–91.

Besseling J, Kastelein JJP, Defesche JC, Hutten BA, Hovingh GK. Association between familial hypercholesterolemia and prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2015;313:1029–36.

Nowis D, Malenda A, Furs K, Oleszczak B, Sadowski R, Chlebowska J, et al. Statins impair glucose uptake in human cells. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2014;2:e000017.

Sampson UK, Linton MF, Fazio S. Are statins diabetogenic? Curr Opin Cardiol. 2011;26:342–7.

Nakata M, Nagasaka S, Kusaka I, Matsuoka H, Ishibashi S, Yada T. Effects of statins on the adipocyte maturation and expression of glucose transporter 4 (SLC2A4): implications in glycaemic control. Diabetologia. 2006;49:1881–92.

Mabuchi H, Higashikata T, Kawashiri M, Katsuda S, Mizuno M, Nohara A, et al. Reduction of serum ubiquinol-10 and ubiquinone-10 levels by atorvastatin in hypercholesterolemic patients. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2005;12:111–9.

Arnaboldi L, Corsini A. Could changes in adiponectin drive the effect of statins on the risk of new-onset diabetes? The case of pitavastatin. Atheroscler Suppl. 2015;16:1–27.

Stroes ES, Thompson PD, Corsini A, Vladutiu GD, Raal FJ, Ray KK, et al. Statin-associated muscle symptoms: impact on statin therapy—European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel Statement on Assessment, Aetiology and Management. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1012–22.

Parker BA, Thompson PD. Effect of statins on skeletal muscle: exercise, myopathy, and muscle outcomes. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2012;40:188–94.

Mampuya WM, Frid D, Rocco M, Huang J, Brennan DM, Hazen SL, et al. Treatment strategies in patients with statin intolerance: the Cleveland Clinic experience. Am Heart J. 2013;166:597–603.

Panza GA, Taylor BA, Thompson PD. An update on the relationship between statins and physical activity. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2016;31:572–9.

Naci H, Brugts J, Ades T. Comparative tolerability and harms of individual statins: a study-level network meta-analysis of 246,955 participants from 135 randomized, controlled trials. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6:390–9.

Culver AL, Ockene IS, Balasubramanian R, Olendzki BC, Sepavich DM, Wactawski-Wende J, et al. Statin use and risk of diabetes mellitus in postmenopausal women in the Women’s Health Initiative. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:144–52.

Robinson JG. Statins and diabetes risk: how real is it and what are the mechanisms? Curr Opin Lipidol. 2015;26:228–35.

Betteridge DJ, Carmena R. The diabetogenic action of statins—mechanisms and clinical implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12:99–110.

Navarese EP, Buffon A, Andreotti F, Kozinski M, Welton N, Fabiszak T, et al. Meta-analysis of impact of different types and doses of statins on new-onset diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:1123–30.

Freeman DJ, Norrie J, Sattar N, Neely RD, Cobbe SM, Ford I, et al. Pravastatin and the development of diabetes mellitus: evidence for a protective treatment effect in the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study. Circulation. 2001;103:357–62.

Carter AA, Gomes T, Camacho X, Juurlink DN, Shah BR, Mamdani MM. Risk of incident diabetes among patients treated with statins: population based study. BMJ. 2013;346:f2610.

Lee J, Noh Y, Shin S, Lim H-S, Park RW, Bae SK, et al. Impact of statins on risk of new onset diabetes mellitus: a population-based cohort study using the Korean National Health Insurance claims database. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2016;12:1533–43.

Sugiyama S, Fukushima H, Kugiyama K, Maruyoshi H, Kojima S, Funahashi T, et al. Pravastatin improved glucose metabolism associated with increasing plasma adiponectin in patients with impaired glucose tolerance and coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2007;194:e43–51.

Yada T, Nakata M, Shiraishi T, Kakei M. Inhibition by simvastatin, but not pravastatin, of glucose-induced cytosolic Ca2+ signalling and insulin secretion due to blockade of L-type Ca2+ channels in rat islet beta-cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;126:1205–13.

Shepherd J, Blauw GJ, Murphy MB, Bollen ELEM, Buckley BM, Cobbe SM, et al. Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1623–30.

Kajinami K, Takekoshi N, Saito Y. Pitavastatin: efficacy and safety profiles of a novel synthetic HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor. Cardiovasc Drug Rev. 2003;21:199–215.

Vallejo-Vaz AJ, Kondapally Seshasai SR, Kurogi K, Michishita I, Nozue T, Sugiyama S, et al. Effect of pitavastatin on glucose, HbA1c and incident diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials in individuals without diabetes. Atherosclerosis. 2015;241:409–18.

Odawara M, Yamazaki T, Kishimoto J, Ito C, Noda M, Terauchi Y, et al. Pitavastatin for the delay or prevention of diabetes development in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance. In: 73th American Diabetes Association Annual Meeting. 2013.

Huang CH, Huang YY, Hsu BRS. Pitavastatin improves glycated hemoglobin in patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Investig. 2016;7:769–76.

Cho Y, Choe E, Lee Y-H, Seo JW, Choi Y, Yun Y, et al. Risk of diabetes in patients treated with HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Metab Clin Exp. 2015;64:482–8.

Kryzhanovski V, Eriksson M, Hounslow N, Sponseller C. Short-term and long-term effects of pitavastatin and simvastatin on fasting plasma glucose in patients with primary hyperlipidemia or mixed dyslipidemia and ≥ 2 risk factors for coronary heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:E1659.

Hulman A, Simmons RK, Brunner EJ, Witte DR, Færch K, Vistisen D, et al. Trajectories of glycaemia, insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion in South Asian and white individuals before diagnosis of type 2 diabetes: a longitudinal analysis from the Whitehall II cohort study. Diabetologia. 2017;60:1252–60.

Lin I, Sung J, Sanchez RJ, Mallya UG, Friedman M, Panaccio M, et al. Patterns of statin use in a real-world population of patients at high cardiovascular risk. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22:685–98.

Lee JK, Grace KA, Foster TG, Crawley MJ, Erowele GI, Sun HJ, et al. How should we measure medication adherence in clinical trials and practice? Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3:685–90.

Choo PW, Rand CS, Inui TS, Lee ML, Cain E, Cordeiro-Breault M, et al. Validation of patient reports, automated pharmacy records, and pill counts with electronic monitoring of adherence to antihypertensive therapy. Med Care. 1999;37:846–57.

Authors’ contributions

JK designed the research, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. HSL performed the statistical analysis and the interpretation of data. KYL participated in the interpretation of all data and the critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This study used the NHIS-HEALS data (NHIS-2018-2-189) made by NHIS.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset (NHIS-HEALS) supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the homepage of National Health Insurance Sharing Service [http://nhiss.nhis.or.kr/bd/ab/bdaba021eng.do]. To gain access to the data, a completed application form, a research proposal and the applicant’s approval document from the institutional review board should be submitted to and reviewed by the inquiry committee of research support in NHIS. Currently, use of NHIS data is allowed only for Korean researchers.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The NHIS-HEALS data were fully anonymized for privacy protection. Due to the retrospective nature and use of de-identified data, this study was approved, and informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board of Bundang CHA Medical Center (2018-05-009).

Funding

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2017R1D1A1B03033382).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, J., Lee, H.S. & Lee, KY. Effect of statins on fasting glucose in non-diabetic individuals: nationwide population-based health examination in Korea. Cardiovasc Diabetol 17, 155 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-018-0799-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-018-0799-4