Abstract

Background

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) regulates blood glucose levels and inflammation, and it is also implicated in the pathophysiological process of myocardial infarction (MI). Plasma DPP4 activity (DPP4a) may provide prognostic information regarding outcomes for ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) patients.

Methods

Blood samples were obtained from 625 consecutively admitted, percutaneous coronary intervention-treated STEMI patients with a mean age of 57 years old. DPP4a was quantified using enzymatic assays.

Results

The median follow-up period was 30 months. Multivariate Cox-regression analyses (adjusted for confounding variables) showed that a 1 U/L increase of DPP4a did not associate with risks of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events (MACCE), cardiovascular mortality, MI, heart failure readmission, stroke, non-cardiovascular mortality and repeated revascularization. However, in a subset of 149 diabetic STEMI patients, DPP4a associated with an increased risk of MACCE (HR 1.16; 95% CI 1.04–1.30; p = 0.01).

Conclusions

DPP4a did not associate with cardiovascular events and non-cardiovascular mortality in non-diabetic STEMI patients. However, DPP4a may be associated with future MACCE in diabetic STEMI patients.

Trial registration NCT03046576, registered on 5 February, 2017, retrospectively registered

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) was identified as a cell surface protein that cleaved amino-terminal dipeptides containing either l-proline or l-alanine at the second to last position. DPP4 inactivated glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), a member of the incretin metabolic hormone family, thus involving it in glucose metabolism [1]. Widespread expression of DPP4 on the surface of myocardial and endothelial cells, and the non-enzymatic function of it as a signaling and binding protein suggest a function in cardiovascular regulation [2]. Data elucidating a potential role for DPP4 in heart failure (HF) have conflicted. The DPP4 inhibitor saxagliptin led to a 27% increase in hospitalization for HF in diabetic patients who had a history of, or were at risk for, cardiovascular events [3]. Use of a DPP4 inhibitor associated with reduced risk of hospitalization for HF when compared with patients receiving antidiabetic sulphonylurea drugs [4]. A recent meta-analysis showed that the relative effects of DPP4 inhibitors on HF risk were uncertain [5]. Conversely, the role of DPP4 in myocardial infarction (MI) was largely consistent across studies. DPP4 inhibition during MI events played a protective role. Either genetic disruption or chemical inhibition of DPP4 improved functional recovery after ischemia/reperfusion injury in an animal MI model [6], and DPP4 inhibitors improved left ventricular diastolic function in diabetic patients with acute MI [7].

DPP4 also exists in a soluble form in the plasma, where it is thought to be shed from the membranes of endothelial cells, while maintaining enzymatic activity [8]. Increased plasma DPP4 activity (DPP4a) predicted both sub-clinical and new-onset atherosclerotic events [9, 10]. Additionally, DPP4a correlated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes in HF [11] as well as sub-clinical left ventricular dysfunction in diabetic patients [12]. Our previous work found that DPP4a was significantly lower in MI patients compared with patients experiencing only chest pain or unstable angina, and DPP4a associated with inpatient no-reflow and major bleeding events in STEMI patients [13]. The no-reflow phenomenon [14] and major bleeding events [15] independently associated with worsened in-hospital and long-term prognoses. Thus, it was hypothesized here that DPP4a may be associated with adverse cardiovascular events during the long-term follow-up period in these patients.

Methods

Study population

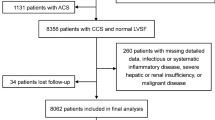

The People’s Liberation Army General Hospital (PLAGH) is a tertiary referral center in Beijing, China. A total of 841 STEMI patients were consecutively admitted between January 2013 and September 2015 to the department of cardiology, PLAGH. All of the 803 STEMI patients who agreed to participate gave written informed consent. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the PLAGH and the Beijing Ethics Association, and is in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Blood samples were collected on the first morning after admission for all patients with acute myocardial infarction. Plasma samples were frozen at −80 °C until further analyses. Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) treatments were administered to 712 participants. Major exclusion criteria for PCI included: conditions requiring treatment with coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) or thrombolytic therapy according to the current standard guidelines [16], uncontrolled hypertension, any substantial trauma, or increased risk of severe bleeding. To enhance homogeneity of the sample and to ensure examination of a representative cohort in the context of contemporary treatment modalities, we further excluded patients with cancer (n = 24; cancer can affect both DPP4a and the outcomes of interest [17]), and patients who were taking a DPP4 inhibitor (n = 26) or a GLP-1 analogue (n = 16). Patients were followed for a median of 30 months (interquartile range 23–44 months), and 21 patients were lost to follow-up. Thus, the final sample size was 625 patients.

The age range of patients was 28–88 years old. Participants did not experience cardiogenic shock, and survived for at least 24 h after PCI treatment. STEMI events were defined as MI with typical cardiac ischemic symptoms, as well as electrocardiographic ischemic changes with ST-segment elevations of >0.1 mm in at least two contiguous leads, and positive cardiac troponin tests. PCI procedures were performed according to current AHA PCI standard guidelines [18]. Post-procedural medications were given according to ACC/AHA guidelines and included: aspirin, clopidogrel, β-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers, nitrates, antidiabetic agents and statins [19].

Outcome events and follow-up

All clinical and demographic properties of the patients were recorded from hospital files and computer records. The primary endpoint for this study was a major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular event (MACCE), defined as either: cardiovascular (CV) death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, heart failure, or stroke. Other endpoints of interest included non-CV death and repeated revascularization. Outcome status, date and etiologies were obtained from follow-up outpatient visits, inpatient clinical records of re-admitted patients, or by telephone interviews in which the moderators were blinded to patients’ DPP4a. There was no adjudication. Revascularization was defined as repeated PCI or bypass grafting of either infarct-related arteries or non-infarct-related arteries, occurring due to either ischemic symptoms (stable/unstable angina or re-infarction) or detections of ischemic events by non-invasive tests. Stroke was defined using World Health Organization-defined criteria [20]. Hypertension was defined as either a blood pressure level of ≥140/90 mmHg by three separate resting sphygmomanometer measurements or the use of an anti-hypertensive agent. Throughout this article, any reference to plasma glucose concentrations pertained to measurements obtained after an overnight fast of at least 8 h, occurring within 24 h of admission. Patients were considered to have type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) if they were previously diagnosed or used anti-diabetic agents prior to admission.

Biochemical measurements

All biomarker measurements were performed by investigators who were blinded to patients’ characteristics and outcomes. Fast plasma glucose, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), creatinine, creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) levels were measured using automated enzymatic methods (Cobas®, Roche, Germany). DPP4 activities were determined in EDTA-treated plasma samples by measuring rates of p-nitroaniline (pNa) cleavage from the synthetic substrate H-Gly-Pro-pNa (L1880, Bachem, Switzerland) by DPP4, as previously described [13]. Briefly, 5 µL plasma samples were added to 150 µL of 50 mM tris–HCl containing 1 mM H-Gly-Pro-pNa. DPP4 activity were expressed as the amount of pNa cleaved per minute per liter (U/L).

Statistical analyses

Data distributions were evaluated for normality by plotting both probability plot and quantile–quantile plot. Continuous variables were expressed as means (±SD), or medians (interquartile ranges) depending on normality. Categorical variables were expressed as counts (percentages). ANOVA, Kruskal–Wallis and Chi square tests were used to compare normally distributed variables, and non-normally distributed continuous and discrete variables, respectively. To evaluate the prognostic value of DPP4a, patients were stratified into DPP4a tertiles. Survival analyses were performed with Kaplan–Meier methods with stratifications by DDP4a tertiles, and results were statistically evaluated with log-rank tests. Cox proportional hazard regression models were applied to query the data for independent predictors of outcomes. Participants were censored upon first presentation of the combined endpoint. To select variables for inclusion in multivariate analyses, univariate Cox proportional hazards models using forward variable selection methods were used. Variables were considered significant in the univariate models when p < 0.05. Other factors included in the multivariate models have been previously shown to associate with MACCE [21]. Model 1 adjusted for age and gender. Model 2, the fully adjusted model, also adjusted for: body mass index; levels of: creatinine, triglycerides, aspartate aminotransferases, CK-MB, pro-brain natriuretic peptides, and fasting plasma glucose; hypertension; smoking; previous myocardial infarction; and use of: ACEI, ARB, statins, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers or diuretics. All statistical tests were two-tailed and differences were considered significance if p values were less than 0.05. All analyses were performed with SPSS 13.0 software (SPSS, IL, USA).

Results

Demographics of the included and excluded patient populations are given in Additional file 1: Table S1. No significant differences between characteristics of the two groups were observed. Demographics of the included participant populations are given in Table 1. The cohort comprised 519 men (81.9%) and 106 women (19.1%) with a mean age of 57.4 ± 11.4 years. The median DPP4a was 27.49 ± 8.76 U/L. No difference in activity level was found between genders (male: 27.49 ± 8.78 U/L, female: 27.46 ± 8.72 U/L; p = 0.97), or between diabetic and non-diabetic patients (diabetic: 26.38 ± 9.21 U/L, non-diabetic: 27.83 ± 8.61 U/L; p = 0.08). Increased DPP4a (by tertiles) negatively associated with histories of hypertension. Conversely, DPP4a positively associated with current smoking status, and levels of ALT and AST (Table 1).

Kaplan–Meier longitudinal analyses showed that patients in the highest DPP4a tertile (DPP4a >31.30 U/L) had similar CV event rates and non-CV mortality rates when compared with patients in the lowest and the middle DPP4a tertiles (all log-rank tests p > 0.05; Fig. 1). Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to quantify the adjusted risk of MACCE. In both unadjusted and adjusted models, DPP4a did not associate with: MACCE (adjusted HR [aHR]: 1.01, 95% CI [0.98–1.05] for 1 U/L increase of DPP4a, p = 0.53), CV mortality, myocardial infarction, HF readmission, stroke and repeated revascularization. In the fully-adjusted model, DPP4a did not associate with increased incidence of non-CV mortality. An additional sub-group analysis was performed to determine whether increased DPP4a was predictive of MACCE in diabetic or non-diabetic patients. One U/L increase of DPP4a associated with an increasing risk of MACCE in diabetic patients (aHR 1.16 [1.04–1.30], p = 0.01), but not non-diabetic patients (aHR 0.98 [0.94–1.03], p = 0.48) in the fully-adjusted models (Table 2).

Results of Kaplan–Meier analysis of cumulative event-free rates in STEMI patients, stratified by DPP4a tertiles. As noted, rates of CV death (a), non-CV death (b), myocardial infarction (c), heart failure (d), and stroke (e) as well as repeated revascularization free-rate (f) were not significantly different among DPP4a tertiles

Discussion

This study demonstrates a lack of evidence that DPP4a predicted MACCE in non-diabetic STEMI patients receiving PCI treatment. However, in this sample, DPP4a may be associated with MACCE in diabetic STEMI patients.

Previous studies have reported that DPP4a did not associate with hypertension in diabetic patients [12], but did associate with new-onset hypertensive events [22]. Our study showed that DPP4a inversely associated with hypertension. In a pre-clinical study, pharmacological inhibition of DPP4 that reduced plasma DPP4a results in improved hypertension rates [23, 24]. In accordance with previous data [25,26,27], the present study found that patients with higher DPP4a had increased liver transaminase and GGT levels. These data support the hypothesis that DPP4 serum enzymatic activity originates from the liver and is linked to insulin resistance [25, 28]. Previous studies reported that hepatitis C viral infections associated with higher DPP4a [29, 30]. In the current study, only one patient was concomitantly infected with hepatitis C virus (based on preoperative immunological results). Thus, the associations observed between DPP4a and liver transaminases and GGT are not related to hepatitis C virus infections in this population. Although a previous study has shown that DPP4a was higher in diabetic populations [12, 31], this trend was not observed in the current study. However, DPP4a is reduced after MI [13], thus diabetic patients may have more severe DPP4a reductions after STEMI than non-diabetic patients.

DPP4a is considered a potential prognostic marker for cardiovascular diseases. Higher plasma DPP4a was associated with worsened cardiovascular outcomes in heart failure patients [11]. Additionally, DPP4a predicted atherosclerotic events in a healthy cohort [10]. Moreover, inhibition of DPP4 gene products, which down-regulated DPP4a [32], decreased mortality after myocardial infarction in diabetic rats [33]. Expression of the DPP4 gene may affect MACCE of STEMI patients in a GLP-1-dependent way. Bioactive GLP-1 was degraded at its N terminus by DPP4 proteins, and inhibition of DPP4 increased expression of active GLP-1 [34]. GLP-1 could protect the heart from ischemic-reperfusion injury. In humans and in animal models, GLP-1 beneficially affected cardiac contractility, blood pressure and cardiac output [35]. GLP-1 improved outcomes after experimentally-induced myocardial infarction [36]. Our group previously found that GLP-1 analog use before PCI associated with improved left ventricular ejection fraction rates in MI patients after a 3-month follow-up [37, 38]. Moreover, DPP4 protein has additional substrates that participate in responses to ischemic heart disease, such as stromal cell-derived factor-1 alpha (SDF1α), neuropeptide Y and substance P [39]. The plasma levels of these substrates associated with adverse events after MI [40,41,42]. Inhibition of DPP4 attenuated post-MI cardiac dysfunction and adverse remodeling events in rats [43, 44] and mice [6]. An earlier study from our group identified that DPP4a associated with no-reflow and in-hospital major bleeding events in STEMI patients [13]. We therefore hypothesized that DPP4a associated with long-term prognoses in STEMI patients.

The data reported here showed that DPP4a did not associated with long-term MACCE in STEMI patients. Although circulating DPP4a was changed in MI patients, it did not predict long-term prognoses. In fact, use of a DPP4 inhibitor, which regulated DPP4a, failed to decrease the incidence of MACCE in humans. Three large randomized clinical trials (SAVOR TIMI, NCT01107886; EXAMINE, NCT00968708; and TECOS, NCT00790205) demonstrated that DPP4 inhibitors did not decrease MACCE risk in diabetic patients with CV diseases [45]. In a recent meta-analysis, DPP4 inhibitors did not affect mortality and CV events [46]. DPP4 may play distinct roles in different aspects of cardiovascular disease that collectively lead to an overall neutral effect on cardiovascular events in STEMI patients. A recent study reported that increased circulating DPP4 levels positively and independently associated with coronary artery disease, even in the absence of DM [31]. These data conflict with the present study. However the previous study was a cross-sectional design and did not study long-term outcomes. Moreover acute MI and unstable angina pectoris were not distinguished in the previous study, while the current study only included STEMI patients. Given these fundamental differences, it is reasonable that the results differed in the two studies.

Diabetes has been consistently associated with more severe myocardial infarction. Indeed, diabetic patients have shown more than twofold greater incidence of acute coronary syndromes and cardiovascular diseases, two to fourfold greater incidence of cardiovascular disease-related mortality, and larger infarct sizes compared to non-diabetic patients [47]. Moreover, diabetes confers an approximately threefold greater odds of post-STEMI right ventricular dysfunction, leading to a worsened prognosis for diabetic MI patients [48]. Since DPP4 is a therapeutic target for diabetes, most studies on DPP4 are carried out in diabetic patients. A previous study found that circulating DPP4 was elevated in type 2 diabetic patients, regardless of coronary artery disease status [31], which associated with subclinical left ventricular dysfunction [12] and subclinical atherosclerosis [9] in these patients. DPP4 inhibitor treatments associated with lower risks of mortality as well as MI and ischemic stroke in diabetic patients with pre-existing heart failures [49]. Additionally, vildagliptin, a DPP4 inhibitor, increased survival rates of diabetic, but not non-diabetic mice [33], suggesting that DPP4 may have a unique role in diabetes. In the current study a subgroup analysis was performed on DPP4a and MACCE in diabetic and non-diabetic STEMI patients. We found that higher DPP4a associated with MACCE in 149 diabetic STEMI patients after adjustment for confounding factors. Given that this study was not powered for diabetic patients (only about 25% of the population was diabetic), a strong conclusion cannot be drawn. The predictive effects of plasma markers may be affected by co-morbid diabetes [50]. Additionally, in the above described studies DPP4 had a positive prognostic role in diabetic patients, and our results were obtained after correcting for all confounding factors. Thus, these data support that a positive correlation exists between DPP4a and MACCE in diabetic patients. Nonetheless, a future study is required that is powered to answer this question.

Limitations

Some limitations existed in the current study. First, the diabetic STEMI patient sub-population was small, as the study was not powered to study this sub-group. Second, the study was limited to inclusion of selected patients from just one center. Third, DPP4 activity was measured at a single time point; additional blood specimens were not collected at other times during patients’ hospital stays or follow-up visits. Peri- or post-operative dynamic changes of DPP4a may provide additional contextual information regarding the role of DPP4 in diabetic STEMI patients.

Conclusions

In summary, the current study showed that circulating DPP4a was not associated with risks of MACCE in non-diabetic STEMI patients. However, DPP4a may have associated with MACCE in diabetic STEMI patients. This possibility will be explored in a future large-sample multi-center trial.

Abbreviations

- CV:

-

cardiovascular

- DPP4:

-

dipeptidyl peptidase-4

- DPP4a:

-

plasma DPP4 activity

- HR:

-

hazard ratio

- MACCE:

-

major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events

- PCI:

-

percutaneous coronary intervention

- STEMI:

-

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

References

Klemann C, Wagner L, Stephan M, von Horsten S. Cut to the chase: a review of CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase-4’s (DPP4) entanglement in the immune system. Clin Exp Immunol. 2016;185(1):1–21.

Zhong J, Maiseyeu A, Davis SN, Rajagopalan S. DPP4 in cardiometabolic disease: recent insights from the laboratory and clinical trials of DPP4 inhibition. Circ Res. 2015;116(8):1491–504.

Scirica BM, Bhatt DL, Braunwald E, Steg PG, Davidson J, Hirshberg B, Ohman P, Frederich R, Wiviott SD, Hoffman EB, et al. Saxagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1317–26.

Fadini GP, Avogaro A, Degli Esposti L, Russo P, Saragoni S, Buda S, Rosano G, Pecorelli S, Pani L. Risk of hospitalization for heart failure in patients with type 2 diabetes newly treated with DPP-4 inhibitors or other oral glucose-lowering medications: a retrospective registry study on 127,555 patients from the Nationwide OsMed Health-DB Database. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(36):2454–62.

Li L, Li S, Deng K, Liu J, Vandvik PO, Zhao P, Zhang L, Shen J, Bala MM, Sohani ZN, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and risk of heart failure in type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised and observational studies. BMJ. 2016;352:i610.

Sauve M, Ban K, Momen MA, Zhou YQ, Henkelman RM, Husain M, Drucker DJ. Genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 improves cardiovascular outcomes after myocardial infarction in mice. Diabetes. 2010;59(4):1063–73.

Fujiwara T, Yoshida M, Nakamura T, Sakakura K, Wada H, Arao K, Katayama T, Funayama H, Sugawara Y, Mitsuhashi T, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors are associated with improved left ventricular diastolic function after acute myocardial infarction in diabetic patients. Heart Vessels. 2015;30(5):696–701.

Mulvihill EE, Varin EM, Gladanac B, Campbell JE, Ussher JR, Baggio LL, Yusta B, Ayala J, Burmeister MA, Matthews D, et al. Cellular sites and mechanisms linking reduction of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 activity to control of incretin hormone action and glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2017;25(1):152–65.

Zheng TP, Liu YH, Yang LX, Qin SH, Liu HB. Increased plasma dipeptidyl peptidase-4 activities are associated with high prevalence of subclinical atherosclerosis in Chinese patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study. Atherosclerosis. 2015;242(2):580–8.

Zheng TP, Yang F, Gao Y, Baskota A, Chen T, Tian HM, Ran XW. Increased plasma DPP4 activities predict new-onset atherosclerosis in association with its proinflammatory effects in Chinese over a four year period: a prospective study. Atherosclerosis. 2014;235(2):619–24.

dos Santos L, Salles TA, Arruda-Junior DF, Campos LC, Pereira AC, Barreto AL, Antonio EL, Mansur AJ, Tucci PJ, Krieger JE, et al. Circulating dipeptidyl peptidase IV activity correlates with cardiac dysfunction in human and experimental heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(5):1029–38.

Ravassa S, Barba J, Coma-Canella I, Huerta A, Lopez B, Gonzalez A, Diez J. The activity of circulating dipeptidyl peptidase-4 is associated with subclinical left ventricular dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2013;12:143.

Li JW, Chen YD, Chen WR, Jing J, Liu J, Yang YQ. Plasma DPP4 activity is associated with no-reflow and major bleeding events in Chinese PCI-treated STEMI patients. Sci Rep. 2016;6:39412.

Niccoli G, Kharbanda RK, Crea F, Banning AP. No-reflow: again prevention is better than treatment. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(20):2449–55.

Pellaton C, Cayla G, Silvain J, Zeymer U, Cohen M, Goldstein P, Huber K, Pollack C Jr, Kerneis M, Collet JP, et al. Incidence and consequence of major bleeding in primary percutaneous intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction in the era of radial access: an analysis of the international randomized acute myocardial infarction treated with primary angioplasty and intravenous enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin to lower ischemic and bleeding events at short- and long-term follow-up trial. Am Heart J. 2015;170(4):778–86.

O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, Ettinger SM, Fang JC, Fesmire FM, Franklin BA, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(4):e78–140.

Javidroozi M, Zucker S, Chen WT. Plasma seprase and DPP4 levels as markers of disease and prognosis in cancer. Dis Markers. 2012;32(5):309–20.

Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Bailey SR, Bittl JA, Cercek B, Chambers CE, Ellis SG, Guyton RA, Hollenberg SM, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Circulation. 2011;124(23):2574–609.

Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, Brindis RG, Fihn SD, Fleisher LA, Granger CB, Lange RA, Mack MJ, Mauri L, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines: an update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention, 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for coronary artery bypass graft surgery, 2012 ACC/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease, 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction, 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes, and 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Circulation. 2016;134(10):e123–55.

Aho K, Harmsen P, Hatano S, Marquardsen J, Smirnov VE, Strasser T. Cerebrovascular disease in the community: results of a WHO collaborative study. Bull World Health Organ. 1980;58(1):113–30.

Zittermann A, Kuhn J, Dreier J, Knabbe C, Gummert JF, Borgermann J. Vitamin D status and the risk of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events in cardiac surgery. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(18):1358–64.

Zheng T, Chen T, Liu Y, Gao Y, Tian H. Increased plasma DPP4 activity predicts new-onset hypertension in Chinese over a 4-year period: possible associations with inflammation and oxidative stress. J Hum Hypertens. 2015;29(7):424–9.

Kawase H, Bando YK, Nishimura K, Aoyama M, Monji A, Murohara T. A dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor ameliorates hypertensive cardiac remodeling via angiotensin-II/sodium-proton pump exchanger-1 axis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;98:37–47.

Aroor AR, Sowers JR, Bender SB, Nistala R, Garro M, Mugerfeld I, Hayden MR, Johnson MS, Salam M, Whaley-Connell A, et al. Dipeptidylpeptidase inhibition is associated with improvement in blood pressure and diastolic function in insulin-resistant male Zucker obese rats. Endocrinology. 2013;154(7):2501–13.

Blaslov K, Bulum T, Knežević-Ćuća J, Duvnjak L. Fasting serum dipeptidyl peptidase-4 activity is independently associated with alanine aminotransferase in type 1 diabetic patients. Clin Biochem. 2015;48(1–2):39–43.

Aso Y, Terasawa T, Kato K, Jojima T, Suzuki K, Iijima T, Kawagoe Y, Mikami S, Kubota Y, Inukai T, et al. The serum level of soluble CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase 4 increases in response to acute hyperglycemia after an oral glucose load in healthy subjects: association with high-molecular weight adiponectin and hepatic enzymes. Transl Res. 2013;162(5):309–16.

Lee SA, Kim YR, Yang EJ, Kwon E-J, Kim SH, Kang SH, Park DB, Oh B-C, Kim J, Heo ST, et al. CD26/DPP4 levels in peripheral blood and T cells in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(6):2553–61.

Firneisz G, Varga T, Lengyel G, Feher J, Ghyczy D, Wichmann B, Selmeci L, Tulassay Z, Racz K, Somogyi A. Serum dipeptidyl peptidase-4 activity in insulin resistant patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a novel liver disease biomarker. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(8):e12226.

Ragab D, Laird M, Duffy D, Casrouge A, Mamdouh R, Abass A, Shenawy DE, Shebl AM, Elkashef WF, Zalata KR, et al. CXCL10 antagonism and plasma sDPPIV correlate with increasing liver disease in chronic HCV genotype 4 infected patients. Cytokine. 2013;63(2):105–12.

Meissner EG, Decalf J, Casrouge A, Masur H, Kottilil S, Albert ML, Duffy D. Dynamic changes of post-translationally modified forms of CXCL10 and soluble DPP4 in HCV subjects receiving interferon-free therapy. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7):e0133236.

Yang G, Li Y, Cui L, Jiang H, Li X, Jin C, Jin D, Zhao G, Jin J, Sun R, et al. Increased plasma dipeptidyl peptidase-4 activities in patients with coronary artery disease. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(9):e0163027.

Wang A, Dorso C, Kopcho L, Locke G, Langish R, Harstad E, Shipkova P, Marcinkeviciene J, Hamann L, Kirby MS. Potency, selectivity and prolonged binding of saxagliptin to DPP4: maintenance of DPP4 inhibition by saxagliptin in vitro and ex vivo when compared to a rapidly-dissociating DPP4 inhibitor. BMC Pharmacol. 2012;12:2.

Murase H, Kuno A, Miki T, Tanno M, Yano T, Kouzu H, Ishikawa S, Tobisawa T, Ogasawara M, Nishizawa K, et al. Inhibition of DPP-4 reduces acute mortality after myocardial infarction with restoration of autophagic response in type 2 diabetic rats. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2015;14:103.

Kieffer TJ, Habener JF. The glucagon-like peptides. Endocr Rev. 1999;20(6):876–913.

Hocher B, Reichetzeder C, Alter ML. Renal and cardiac effects of DPP4 inhibitors—from preclinical development to clinical research. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2012;36(1):65–84.

Noyan-Ashraf MH, Momen MA, Ban K, Sadi AM, Zhou YQ, Riazi AM, Baggio LL, Henkelman RM, Husain M, Drucker DJ. GLP-1R agonist liraglutide activates cytoprotective pathways and improves outcomes after experimental myocardial infarction in mice. Diabetes. 2009;58(4):975–83.

Chen WR, Hu SY, Chen YD, Zhang Y, Qian G, Wang J, Yang JJ, Wang ZF, Tian F, Ning QX. Effects of liraglutide on left ventricular function in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2015;170(5):845–54.

Chen WR, Shen XQ, Zhang Y, Chen YD, Hu SY, Qian G, Wang J, Yang JJ, Wang ZF, Tian F. Effects of liraglutide on left ventricular function in patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Endocrine. 2016;52(3):516–26.

Lei Y, Hu L, Yang G, Piao L, Jin M, Cheng X. Dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibition for the treatment of cardiovascular disease—recent insights focusing on angiogenesis and neovascularization. Circ J. 2017;81(6):770–6.

Fortunato O, Spinetti G, Specchia C, Cangiano E, Valgimigli M, Madeddu P. Migratory activity of circulating progenitor cells and serum SDF-1α predict adverse events in patients with myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;100(2):192–200.

Cuculi F, Herring N, De Caterina AR, Banning AP, Prendergast BD, Forfar JC, Choudhury RP, Channon KM, Kharbanda RK. Relationship of plasma neuropeptide Y with angiographic, electrocardiographic and coronary physiology indices of reperfusion during ST elevation myocardial infarction. Heart. 2013;99(16):1198–203.

Ng LL, Sandhu JK, Narayan H, Quinn PA, Squire IB, Davies JE, Struck J, Bergmann A, Maisel A, Jones DJ. Pro-substance p for evaluation of risk in acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(16):1698–707.

Connelly KA, Zhang Y, Advani A, Advani SL, Thai K, Yuen DA, Gilbert RE. DPP-4 inhibition attenuates cardiac dysfunction and adverse remodeling following myocardial infarction in rats with experimental diabetes. Cardiovasc Ther. 2013;31(5):259–67.

Apaijai N, Inthachai T, Lekawanvijit S, Chattipakorn SC, Chattipakorn N. Effects of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor in insulin-resistant rats with myocardial infarction. J Endocrinol. 2016;229(3):245–58.

Ghosal S, Sinha B. Gliptins and cardiovascular outcomes: a comparative and critical analysis after TECOS. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:1643496.

Savarese G, D’Amore C, Federici M, De Martino F, Dellegrottaglie S, Marciano C, Ferrazzano F, Losco T, Lund LH, Trimarco B, et al. Effects of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors and sodium-glucose linked cotransporter-2 inhibitors on cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2016;220:595–601.

Lejay A, Fang F, John R, Van JA, Barr M, Thaveau F, Chakfe N, Geny B, Scholey JW. Ischemia reperfusion injury, ischemic conditioning and diabetes mellitus. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;91:11–22.

Roifman I, Ghugre N, Zia MI, Farkouh ME, Zavodni A, Wright GA, Connelly KA. Diabetes is an independent predictor of right ventricular dysfunction post ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15:34.

Ou SM, Chen HT, Kuo SC, Chen TJ, Shih CJ, Chen YT. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and cardiovascular risks in patients with pre-existing heart failure. Heart. 2017;103(6):414–20.

Zhao D, Yang LY, Wang XH, Yuan SS, Yu CG, Wang ZW, Lang JN, Feng YM. Different relationship between ANGPTL3 and HDL components in female non-diabetic subjects and type-2 diabetic patients. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15(1):132.

Authors’ contributions

JWL was responsible for the conception and design of the study. WRC and QY analyzed the data. BL wrote the manuscript. HZ contributed to the discussion and reviewed/edited the manuscript. YZ and TWH analyzed the data and contributed to the discussion. YDC reviewed/edited the manuscript and gave the final approval for the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All study data will be available on request.

Consent for publication

All authors consented to the publication of the study data.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol and all procedures received approval from the ethics committee of the PLAGH and the Beijing Ethics Association. Studies conformed with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent documents were obtained from all subjects prior to any study related procedures or measurements.

Funding

This study was supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2016M603025) and the Pilot Foundation of the Beijing Lisheng Cardiovascular Health Foundation (LHJJ201611827).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, JW., Chen, YD., Chen, WR. et al. Prognostic value of plasma DPP4 activity in ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Diabetol 16, 72 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-017-0553-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-017-0553-3