Abstract

Background

Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) lead to a significant reduction in quality of life and an increased mortality risk. Current guidelines strongly recommend pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) after a severe exacerbation. Studies reporting referral for PR are scarce, with no report to date in Europe. Therefore, we assessed the proportion of French patients receiving PR after hospitalization for COPD exacerbation and factors associated with referral.

Methods

This was a national retrospective study based on the French health insurance database. Patients hospitalized in 2017 with COPD exacerbation were identified from the exhaustive French medico-administrative database of hospitalizations. In France, referral to PR has required as a stay in a specialized PR center or unit accredited to provide multidisciplinary care (exercise training, education, etc.) and admission within 90 days after discharge was assessed. Multivariate logistic regression was used to assess the association between patients’ characteristics, comorbidities according to the Charlson index, treatment, and PR uptake.

Results

Among 48,638 patients aged ≥ 40 years admitted for a COPD exacerbation, 4,182 (8.6%) received PR within 90 days after discharge. General practitioner’s (GP) density (number of GPs for the population at regional level) and PR center facilities (number of beds for the population at regional level) were significantly correlated with PR uptake (respectively r = 0.64 and r = 0.71). In multivariate analysis, variables independently associated with PR uptake were female gender (aOR 1.36 [1.28–1.45], p < 0.0001), age (p < 0.0001), comorbidities (p = 0.0013), use of non-invasive ventilation and/or oxygen therapy (aOR 1.52 [1.41–1.64], p < 0.0001) and administration of long-acting bronchodilators (p = 0.0038).

Conclusion

This study using the French nationally exhaustive health insurance database shows that PR uptake after a severe COPD exacerbation is dramatically low and must become a high-priority management strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are defined as events characterized by dyspnea and/or cough and sputum that worsens over less than 14 days [1]. Such exacerbations worsen symptoms, obstruct airflow, impact quality of life and increase the mortality risk, particularly among patients requiring hospitalization, hence called as severe exacerbation [2, 3]. Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is a global management approach that includes not only exercise training but also education and behavioral changes. In France, most PR programs are usually carried out over 3 to 6 weeks in dedicated centers, even if ambulatory care is increasingly prescribed. Guidelines strongly recommend PR after hospitalization for a COPD exacerbation [4,5,6] for its beneficial effect on exercise capacity, health-related quality of life and reduced readmissions and mortality [7, 8]. However, PR referral and uptake rates remain dramatically low [9]. For example, the referral rate ranged from only 1.9% to 30% in carefully selected populations, with fewer than 10% of patients completing the program [10,11,12].

The present study is the first to focus on PR uptake in a French exhaustive nationwide insurance database, covering more than 99% of the whole French population. Barriers to referral and uptake are complex and multi-factorial [13]. However, several factors are known to be associated with a higher PR uptake, such as younger age, living closer to a PR facility, lower comorbidity scores [9] and practitioner delivering PR [14]. For instance, among primary care physicians, a survey found that although two-thirds reported having PR available for their patients, only 38% routinely referred their COPD patients for it [15]. One of the greatest barriers to PR referrals is a lack of knowledge of PR among providers [16]. Identifying and mitigating risk factors for underutilization of PR at a national and international level is therefore essential.

Our first objective was to assess the rate of patients receiving PR after a severe exacerbation of COPD in France using the exhaustive French medico-administrative hospitalizations database. We also investigated which clinical and sociological factors could contribute to PR. Finally, we correlated PR uptake to medical density defined by the number of general practitioners (GPs) and pulmonologists relative to the same regional population in France. Similar analyses were performed for the number and facilities of PR centers, defined by the number of PR centers and number of beds relative to the same region.

Methods

Data sources

This retrospective study was based on the French health insurance database (SNDS, "Système National Des Données de Santé") from the 1st January to the 31st December 2017. The SNDS covers more than 99% of the French population and comprises three existing databases: the French health insurance database which contains all primary care reimbursed; the French national hospital discharge database (PMSI, Programme de médicalisation des systèmes d’information), which includes hospital diagnoses and medical procedures performed during each stay in French public and private hospitals; and the national death registry. The SNDS database includes information on the presence of long-term diseases (ALD, affection de longue durée) and reimbursable drugs. According to the International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD 10), diagnoses are coded as principal diagnosis (PD: condition requiring hospitalization), related diagnosis (RD) and secondary associated diagnosis (SAD: complications and co-morbidities potentially affecting the course or cost of hospitalization) [17].

Study population

Our study included patients aged 40 years and older with a permanent address in France. Hospitalization was defined as an in-hospital stay of at least one night, ending in 2017, with a PD of COPD, or with a PD of COPD exacerbation associated with an SAD of COPD, or with a PD of a disease that may trigger a COPD exacerbation (influenza, pulmonary embolism, acute heart failure, acute respiratory failure, pneumothorax) associated with an SAD of COPD [18]. To focus on individuals who were systematically eligible for PR after a COPD exacerbation, we applied the following exclusion criteria, which were not mutually exclusive: (i) patients who died during stay, (ii) patients hospitalized for more than one night within 90 days after discharge or transfer to another acute care facility, hospice, long-term care facility, (iii) patients suffering from Alzheimer or other active dementia (Fig. 1).

Outcome

PR was defined as a stay in a medical unit or a center entirely specialized in the management of respiratory diseases within 90 days of hospital discharge. These centers and units provide multidisciplinary care (exercise training, education, etc.) as recommended in international guidelines [1] and must meet a set of specifications in order to be coded as “PR center” or “unit” in the SNDS database. For patients with several stays, only the first was analyzed.

Patients: spatial health inequalities and healthcare system

The Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) was used to estimate the weight of comorbidities the year before the study period [19, 20]. To facilitate the analyses, its principal components were gathered into major categories as described in [18]. In addition, the presence of a long-term chronic disease in 2017, called ALD (“Affection de Longue Durée”) in France, was also studied. The combined use of these two factors allowed us to distinguish between (a) comorbidities present at the time of admission to hospital, regardless of their severity (thanks to the CCI) and (b) comorbidities deemed serious enough to require an ALD.

Spatial health inequalities were estimated in terms of the French Deprivation Index (FDEP) and French Free Universal Health Care, (CMU-C, “Couverture Médicale Universelle Complémentaire”). The FDEP is based on four components (median household income, proportion of secondary school graduates among inhabitants aged 15 years and over, percentage of blue-collar workers in the active population, and proportion of unemployed) and 2013 is the most recent available data. The first quintile (Q1) corresponds to the 20% of the population living in the least deprived municipalities, while the fifth quintile (Q5) corresponds to the 20% living in the most deprived municipalities [21, 22].

Healthcare consumption in 2017 was described by the number of dispensations of inhaled long-acting bronchodilator (to estimate the background treatment), oxygen or non-invasive ventilation, contacts with healthcare providers (GPs and pulmonologists) and rehabilitation care in the year preceding the index hospitalization for COPD exacerbation. Analyses of the 7-day GP and 60-day pulmonologist follow-up excluded patients receiving PR respectively during the first 7 days and the first 60 days, because they were already receiving regular medical follow-up as part of their PR program and may not have had any additional external consultations.

Ethics, consent and statistical analyses

This work was carried out by the HAS (Haute Autorité de Santé) whose aim is to design COPD-specific quality of care indicators based on French guidelines and workshops with experts (GPs, pulmonologists, expert patients, pharmacists, nutritionists, physiotherapists, physical and rehabilitation physician, professional pathologist, public health physician). According to French Law [19], this anonymous retrospective observational database study does not require approval by an ethics committee or informed signed consent from the patients.

Categorial variables were compared by Chi-square tests. Continuous variables were summarized as mean ± standard deviation or median [Q1–Q3] and were compared by Student tests, because of the sufficiently large sample size. The association between PR and hospitalization for COPD exacerbation was estimated by a multivariate logistic regression model and quantified by adjusted ORs (aOR) and their confidence intervals (95% CIs). Significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. The variables included in the multivariate model were chosen according to their clinical relevance. Analyses were performed using SAS Entreprise Guide version 7.15 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and GraphPad Prism software.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

From the SNDS databases, we identified 95,251 patients aged ≥ 40 years with an in-hospital stay for a severe COPD exacerbation ending between the 1st January 2017 and the 31st December 2017 (Fig. 1).

At the time of index hospitalization, from the remaining eligible 48,638 patients admitted for a severe acute exacerbation of COPD, 66.2% had a PD of COPD. All others had COPD as an SAD and acute heart failure (14.3%), pneumonia (9.5%) or acute respiratory failure (5.9%) as PD. Subjects’ characteristics are described in Table 1. Briefly, median age was 75 [IQR 65–83] years, the majority were males (60.7%) and mortality rate at 6 months after hospital discharge was 7.8%. Regarding the FDEP, 50% of the patients were in the 4th and 5th quintiles corresponding to the most disadvantaged classes. The details of comorbidities assessed by ALD classification are shown in Additional file 1: Table S1 and concerned more than 80% of the patients. The median CCI was 5 [IQR 3–6], and the main comorbidities were diseases of the circulatory system, followed by diabetes mellitus, cancers and renal diseases, respectively corresponding to 32.4%, 22.3%, 15.2% and 7.1% of the patients.

Regarding treatments, median long-acting bronchodilator prescription was 8 [IQR 1–11] per patient per year. However, 19.5% had no bronchodilator prescription and 66.5% of the patients had four drug deliveries or more. Finally, 13.5% of the patients received home oxygen therapy and 3.5% were treated with non-invasive ventilation. Furthermore, 38% of patients had a medical follow-up at day 7 and 28% a respiratory follow-up at day 60 (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Main outcome

Among 48,638 patients admitted for a severe acute exacerbation of COPD, only 4,182 patients (8.6%, 7.6% among men versus 10.2% among women, p < 0.0001) received PR in the 90 days following discharge (Fig. 1). Moreover, COPD as PD was associated with a higher PR uptake (9.1% among patients with COPD as PD versus 7.6% among patients with COPD as SAD, p < 0.0001). The mean delay between discharge and the first rehabilitation care was 6.3 ± 17.6 days (Additional file 1: Table S3).

Factors associated with PR

In univariate analysis (Table 2), patients who received PR were significantly, older (75.5 ± 11.6 versus 73.3 ± 12.2 years, p < 0.0001) and the proportion of women was higher (46.4% versus 38.6%, p < 0.00001). Considering ALD status, comorbidities were more frequent among patients receiving PR (86.5% versus 82.0%, p < 0.0001). According to the CCI, patients admitted to PR had significantly more chronic lung diseases (85.6% versus 76.8% p < 0.0001) the year before hospitalization. They had a lower socioeconomic status and a lower PR admission rate, according to the deprivation index and to data on beneficiaries of CMU-C. Compared to those without PR, a higher proportion of patients admitted to PR already received PR or outpatient physiotherapy sessions care during the year before the index COPD admission (46.3% versus 29.1%, p < 0.0001).

Patients who received PR more often had at least four drug deliveries in 2017 (68.6% versus 66.3% p = 0.04). They also more often received oxygen therapy (18.2% versus 13.1%, p < 0.0001) and non-invasive ventilation (5.6% versus 3.3%, p < 0.0001) in 2017. Patients admitted to PR were more frequently followed by a pulmonologist after hospitalization (43.3% versus 31.7%, p < 0.0001). Finally, the mortality rate 6 months after hospital discharge was higher in the PR subgroup (12.6% versus 7.4%, p < 0.0001).

In multivariable analysis (Table 3), patients who received PR were more often women (aOR = 1.4, [1.3–1.5], p < 0.0001) and aged 60 years and older (aOR vary to 1.5 to 1.9 by age group per 5 years, p < 0.0001). According to the CCI, patients with comorbidities had significantly higher PR uptake (CCI ≥ 5, aOR = 2.9, [1.4–5.8], p < 0.0001). Healthcare consumption, defined as non-invasive ventilation and/or oxygen therapy and/or prescription of inhaled long-acting bronchodilators, was also significantly associated with PR (respectively aOR = 1.5, [1.4–1.6], p < 0.0001 and aOR 1.1 to 1.2, according to the number of deliveries ranging from 1 to more than 4, p = 0.0038).

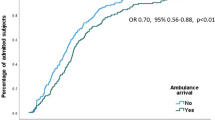

Geographic analyses of PR disparities

Geographical variations concerning PR uptake were also evaluated (Fig. 2). As expected, we noted regional disparities, from 2% in the overseas departments to 12.5% in southeast France (Provence-Alpes-Cote d'Azur Region). Interestingly, GP density was significantly correlated with PR uptake, whereas pulmonologist density was not (respectively r = 0.64, p = 0.01 and r = 0.50, p = 0.07, Fig. 3A, B). PR center facilities, according to the number of beds in conventional hospitalization and the number of ambulatory places, were significantly correlated with PR uptake (r = 0.71, p = 0.005, Fig. 3D), but not with PR center number.

Pulmonary rehabilitation uptake according to number of physicians. A GP density, B pulmonologist density, C pulmonary rehabilitation centers, D pulmonary rehabilitation center capacity (based on number of beds), from the SIRSé (Système d’Information Interrégional en Santé). GPs: general practitioners, PR: pulmonary rehabilitation

Discussion

In this large population database covering more than 99% of the entire French population, we found that among the 48,638 eligible patients, only 4,182 (8.6%) received PR within the 90 days after discharge for a severe exacerbation of COPD in 2017, a figure that is dramatically low in view of the recommendations [4,5,6]. COPD as PD was related to a higher PR uptake because respiratory symptoms may be at the forefront for these patients. In the USA, Spitzer et al. [12] found 1.9% of PR uptake 6 months after hospitalization for a COPD exacerbation and 2.7% at 12 months. Vercammen-Grandjean et al. [23] reported similar findings. Both highlight the gap between recommendation and practice. Our study is the first to report such a result in a European country. Although very low, our rate seems higher, especially since we chose a 3-month delay, whereas Spitzer et al. [12] chose 6 months and Vercammen-Grandjean et al. [23] 12 months. The design of the French health care system, where PR programs after a severe exacerbation of COPD are usually carried out in subacute care in-patient post-hospitalization over 3 to 6 weeks could have contributed to low PR uptake [24].

No formal validation of the ideal interval between discharge and rehabilitation exists in the literature. Based on a systematic review including 13 randomized controlled trials [25], the GOLD report highlighted a reduction in hospitalization in patients who had an exacerbation within the previous 4 weeks [1]. Nevertheless, a large US cohort of more than 190,000 patients hospitalized for COPD reported a significant association between PR initiation within 90 days after discharge and a lower risk of mortality and fewer re-hospitalizations at one year [8, 9]. At the very least, research considering interventions to improve or maintain physical activity in the immediate post-discharge period following COPD exacerbation is needed to test whether this can improve outcomes and reduce the risk of readmission [26].

Features related to PR uptake

Controversial results exist concerning gender. A higher proportion of women were admitted to PR in Vercammen-Grandjean et al. [23] as in the present study contrary to what was published by Spitzer et al. [12]. Compared to men, women with COPD have a lower quality of life, face a more rapid decline in lung function [27] and more frequent anxiety and depression, which could lead to higher healthcare consumption [28]. Moreover, Souto-Miranda et al. [29] showed that women suffer more activity-related dyspnea, severe hyperinflation, frequent exacerbation and hospitalization, which could explain why women were more frequently referred for PR.

We found that patients who were older, who required more oxygen or NIV or who had more comorbidities were significantly more likely to receive PR. They also received more often PR or outpatient physiotherapy sessions the year before the index COPD admission. Taken together, these results demonstrate that disease severity is an important factor associated with PR uptake. Regarding the age of patients, our results differ from those of other studies [12, 23] and highlight the impact of the organization of healthcare. Although the SNDS database does not contain precise clinical information, we think that some elderly and comorbid patients could correspond to Fried's frailty concept (weight loss, exhaustion, low physical activity, slowness and weakness) [30]. In a cohort of 816 COPD patients aged 70 ± 10 years, Maddock et al. [31] showed that 61.3% of patients admitted to rehabilitation no longer had frailty criteria after their stay, meaning that patients with more severe COPD may derive a greater benefit from PR. Also, older patients with more frequent co-morbidities or patients with a more severe COPD, assessed by requiring ventilatory support or oxygen therapy, have greater functional limitations and experience a negative impact on their activities of daily living, which may explain the better PR uptake. However, PR is indicated much earlier in the management of COPD patients and not only at this level of severity, which is a major point for improvement.

As found elsewhere, lower socioeconomic status, according to the CMU-C and the deprivation index, seems to be associated with lower PR uptake and could also be a target for improvement [32, 33].

Healthcare system and PR

The distance between home and rehabilitation center are well established factors of failure [34]. PR uptake varied from 2 to 12.5% according to the different regions in our study. The study design did not allow us to discriminate the rates of PR participation in accordance to living area of each patient, however we have shown that PR uptake is correlated to PR facilities in the same region highlighting the importance of helping easy access. Consistent with this findings, Hug et al. [35] reported that environmental context, resource factors (travel distance, transport, parking, difficulties in fitting programs in with work or family obligations) were frequent barriers for PR uptake.

We also found a correlation between regional GP density and PR uptake. In a study of 252 primary care professionals in UK, Watson et al. [36] showed that those who had a respiratory qualification (63%) referred more patients to rehabilitation (59.1%) than those without it (32.2%), again emphasizing the crucial role of GPs in patient management.

We noticed that 19.5% of the patient did not have any bronchodilator prescription during the study period. It may be explained by a lack of therapeutic education or adherence to treatment however, we can not exclude a lack of prescription due to the design of our study. Various possibilities for improvement exist such as educational programs, electronic tools, collaboration with GPs and providers. One of the options would be to promote flexibility in PR programs regarding schedules and location. The development of tele-rehabilitation techniques could allow better adherence and better access for the most isolated or working patients [37], especially since this is a safe practice and with results possibly close to those of traditional center-based pulmonary rehabilitation [38, 39]. Social isolation and lack of intrinsic motivation are also barriers to rehabilitation [35]. Patient associations could be a major contributor in promoting the benefits of PR by giving direct feedback to the most isolated or anxious patients.

Our work has several strengths that distinguish it from previous publications thanks to the exhaustiveness of the French national healthcare insurance database. It is the first to focus on PR uptake in the entire French insurance database with such a high number of patients. However, the study also has some limitations. First, undiagnosed COPD patients were not included in the analysis, yet one of the major issues of this disease is under-diagnosis [40]. Nevertheless, severe acute COPD of requiring hospitalizations concerns rather the advanced stages of COPD, where hopefully diagnosis is available relatively more often. Second, the potential for unmeasured confounding remains. The SNDS database allows the accurate identification of certain factors, including readmissions, death, comorbidities, and reginal characteristics. However, it lacks significant additional details such as objective data for disease severity (Pulmonary Function Testing), adherence to recommended pharmacotherapy, willingness to participate in PR program, details about number and type of PR sessions delivered, and other social, psychological and environmental factors that are documented barriers to initiating PR. Among people with COPD who are suitable for PR, fewer than a half were really referred to PR programs, yet we are unable to determine whether physicians failed to refer patients for PR or whether the latter chose not to enroll [35]. Finally, we focused on in-patient PR, even though ambulatory strategies are emerging and should be considered in the future to confirm our data in this population.

Despite these limitations, the current study underscores some critical issues that deserve attention. PR uptake after a severe exacerbation of COPD is unacceptably low and is very heterogeneous around in France. Geographic inaccessibility for many deserving patients and subsequent health disparities remain a major issue [12]. While we focused on PR in health care institutions, we now need data on outpatient PR through specific coding and its promotion by the French health insurance system.

Conclusion

In the French national health insurance database, PR after a severe COPD exacerbation was received by less than a tenth of the COPD population and was associated with the density of medical practitioners and PR center facilities. To move personalized COPD medicine forward, we identified several patient-related (age, gender, comorbidities) and social risk factors (lower socio-economic status) associated with an increased risk of non-uptake of PR. Strategies to promote PR and to reinforce strong collaboration between healthcare establishments and primary care as well as pulmonologists and GPs could increase PR uptake after a severe COPD exacerbation. Home-based programs and tele-rehabilitation could become one of the key solutions to promote greater availability and accessibility to PR.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ALD:

-

Affection longue durée (presence of long-term disease)

- CMU-c:

-

Couverture médicale universelle complémentaire (French free universal health care)

- COPD:

-

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- FDEP:

-

French deprivation index

- GP:

-

General practitioners

- HAS:

-

Haute Autorité de Santé (health authority whose objective is to design specific COPD quality of care indicators)

- ICD 10:

-

International classification of disease 10th revision

- PD:

-

Principal diagnosis

- PMSI:

-

Programme de médicalisation des systems d’information (French national hospital discharge database which includes hospital diagnosis and medical procedures performed during each stay in French public and private hospitals

- PR:

-

Pulmonary rehabilitation

- RD:

-

related diagnosis

- SAD:

-

secondary associated diagnosis

- SNDS:

-

Système National des Données de Santé (central French health insurance linking the other databases mentioned above such as PMSI and DCIR)

References

2023 GOLD Report. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease - GOLD. [cité 7 janv 2023]. Disponible sur: https://goldcopd.org/2023-gold-report-2/

Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11): e442.

Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Bourbeau J, et al. Global Strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 Report: GOLD executive summary. Respirology avr. 2017;22(3):575–601.

Criner GJ, Bourbeau J, Diekemper RL, Ouellette DR, Goodridge D, Hernandez P, et al. Prevention of acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest avr. 2015;147(4):894–942.

Wedzicha JA, Miravitlles M, Hurst JR, Calverley PMA, Albert RK, Anzueto A, et al. Management of COPD exacerbations: a European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society guideline. Eur Respir J mars. 2017;49(3):1600791.

2022 GOLD Reports [Internet]. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease—GOLD. [cité 20 avr 2022]. Disponible sur: https://goldcopd.org/2022-gold-reports-2/

Puhan MA, Gimeno-Santos E, Cates CJ, Troosters T. Pulmonary rehabilitation following exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016(12): CD005305.

Lindenauer PK, Stefan MS, Pekow PS, Mazor KM, Priya A, Spitzer KA, et al. Association between initiation of pulmonary rehabilitation after hospitalization for COPD and 1-year survival among medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1813–23.

Stefan MS, Pekow PS, Priya A, ZuWallack R, Spitzer KA, Lagu TC, et al. Association between initiation of pulmonary rehabilitation and rehospitalizations in patients hospitalized with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204(9):1015–23.

Jones SE, Green SA, Clark AL, Dickson MJ, Nolan AM, Moloney C, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation following hospitalisation for acute exacerbation of COPD: referrals, uptake and adherence. Thorax. 2014;69(2):181–2.

on behalf of the Initiatives BPCO (bronchopneumopathie chronique obstructive) Scientific Committee and Investigators, Carette H, Zysman M, Morelot-Panzini C, Perrin J, Gomez E, et al. Prevalence and management of chronic breathlessness in COPD in a tertiary care center. BMC Pulm Med. 2019;19(1):95.

Spitzer KA, Stefan MS, Priya A, Pack QR, Pekow PS, Lagu T, et al. Participation in pulmonary rehabilitation after hospitalization for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among medicare beneficiaries. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16(1):99–106.

Jones SE, Barker RE, Nolan CM, Patel S, Maddocks M, Man WDC. Pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(Suppl 12):S1390–9.

Barker RE, Kon SS, Clarke SF, Wenneberg J, Nolan CM, Patel S, et al. COPD discharge bundle and pulmonary rehabilitation referral and uptake following hospitalisation for acute exacerbation of COPD. Thorax. 2021;76(8):829–31.

COPD: tracking perceptions of individuals affected, their caregivers, and the physicians who diagnose and treat them.

Milner SC, Boruff JT, Beaurepaire C, Ahmed S, Janaudis-Ferreira T. Rate of, and barriers and enablers to, pulmonary rehabilitation referral in COPD: a systematic scoping review. Respir Med avr. 2018;137:103–14.

Tuppin P, Rudant J, Constantinou P, Gastaldi-Ménager C, Rachas A, de Roquefeuil L, et al. Value of a national administrative database to guide public decisions: From the système national d’information interrégimes de l’Assurance Maladie (SNIIRAM) to the système national des données de santé (SNDS) in France. Revue d’Épidémiologie et de Santé Publique. 2017;65:S149–67.

Molinari N, Chanez P, Roche N, Ahmed E, Vachier I, Bourdin A. Rising total costs and mortality rates associated with admissions due to COPD exacerbations. Respir Res. 2016;17:149.

Bannay A, Chaignot C, Blotière PO, Basson M, Weill A, Ricordeau P, et al. The best use of the Charlson comorbidity index with electronic health care database to predict mortality. Med Care févr. 2016;54(2):188–94.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Disv. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Townsend, P. (1987) Deprivation. Journal of Social Policy, 16, 125-146. - References - Scientific Research Publishing. [cité 20 avr 2022]. Disponible sur: https://www.scirp.org/%28S%28vtj3fa45qm1ean45vvffcz55%29%29/reference/referencespapers.aspx?referenceid=1494328

Rey G, Jougla E, Fouillet A, Hémon D. Ecological association between a deprivation index and mortality in France over the period 1997–2001: variations with spatial scale, degree of urbanicity, age, gender and cause of death. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:33.

Vercammen-Grandjean C, Schopfer DW, Zhang N, Whooley MA. Participation in pulmonary rehabilitation by veterans health administration and medicare beneficiaries after hospitalization for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2018;38(6):406–10.

Han MK, Martinez CH, Au DH, Bourbeau J, Boyd CM, Branson R, et al. Meeting the challenge of COPD care delivery in the USA: a multiprovider perspective. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(6):473–526.

Ryrsø CK, Godtfredsen NS, Kofod LM, Lavesen M, Mogensen L, Tobberup R, et al. Lower mortality after early supervised pulmonary rehabilitation following COPD-exacerbations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18(1):154.

Spitzer KA, Stefan MS, Priya A, Pack QR, Pekow PS, Lagu T, et al. A geographic analysis of racial disparities in use of pulmonary rehabilitation after hospitalization for COPD exacerbation. Chest. 2020;157(5):1130–7.

Buttery SC, Zysman M, Vikjord SAA, Hopkinson NS, Jenkins C, Vanfleteren LEGW. Contemporary perspectives in COPD: Patient burden, the role of gender and trajectories of multimorbidity. Respirology. 2021;26(5):419–41.

Martinez CH, Raparla S, Plauschinat CA, Giardino ND, Rogers B, Beresford J, et al. Gender differences in symptoms and care delivery for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Womens Health. 2012;21(12):1267–74.

Souto-Miranda S, van’t Hul AJ, Vaes AW, Antons JC, Djamin RS, Janssen DJA, et al. Differences in pulmonary and extra-pulmonary traits between women and men with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Med. 2022;11(13):3680.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146-156.

Maddocks M, Kon SSC, Canavan JL, Jones SE, Nolan CM, Labey A, et al. Physical frailty and pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD: a prospective cohort study. Thorax. 2016;71(11):988–95.

Oates GR, Hamby BW, Stepanikova I, Knight SJ, Bhatt SP, Hitchcock J, et al. Social determinants of adherence to pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Chronic Obstruct Pulm Dis. 2017;14(6):610–7.

Grosbois JM, Heluain-Robiquet J, Machuron F, Terce G, Chenivesse C, Wallaert B, et al. Influence of socioeconomic deprivation on short- and long-term outcomes of home-based pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;31(14):2441–9.

Hayton C, Clark A, Olive S, Browne P, Galey P, Knights E, et al. Barriers to pulmonary rehabilitation: characteristics that predict patient attendance and adherence. Respir Med. 2013;107(3):401–7.

Hug S, Cavalheri V, Gucciardi DF, Hill K. An evaluation of factors that influence referral to pulmonary rehabilitation programs among people with COPD. Chest. 2022;162(1):82–91.

Watson JS, Jordan RE, Adab P, Vlaev I, Enocson A, Greenfield S. Investigating primary healthcare practitioners’ barriers and enablers to referral of patients with COPD to pulmonary rehabilitation: a mixed-methods study using the Theoretical Domains Framework. BMJ Open. 2022;12(1): e046875.

Spielmanns M, Gloeckl R, Jarosch I, Leitl D, Schneeberger T, Boeselt T, et al. Using a smartphone application maintains physical activity following pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2021-218338.

Cox NS, Dal Corso S, Hansen H, McDonald CF, Hill CJ, Zanaboni P, et al. Telerehabilitation for chronic respiratory disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;1: CD013040.

Cox NS, McDonald CF, Mahal A, Alison JA, Wootton R, Hill CJ, et al. Telerehabilitation for chronic respiratory disease: a randomised controlled equivalence trial. Thorax. 2022;77(7):643–51.

Çolak Y, Afzal S, Nordestgaard BG, Vestbo J, Lange P. Prognosis of asymptomatic and symptomatic, undiagnosed COPD in the general population in Denmark: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(5):426–34.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the expert panel composed of Mme Marie-Alix Alix, Dr. Laurence Amouyel, Pr. Pascal Andujar, M. Anthony Bender, Mme Karine Bernezet, Dr. Anthony Chapron, Dr Marie-Caroline Clement, Dr. Catherine De Bournonville, Mme Rita Goufle, Dr Gilles Madelon, Dr. Christian Michel, Dr. Yasmine Mokaddem, M. Denoël Ohouo, Dr. Jacques Piquet, Dr. Thierry Plagneux, Mme Christiane Pochulu, Dr. Antoine Rachas, Dr. Amandine Rapin, Dr. Philippe Tangre, Dr. Joëlle Texereau, Pr. Ronan Thibault, Dr. Vincent Van Bockstael, Dr. Florent Verfaillie, Dr. Maéva Zysman. The authors also thank the HAS (Haute Autorité de Santé), CNAM (Caisse Nationale d’Assurance Maladie) and ATIH (Agence Technique de l’Information sur l’Hospitalisation).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MG: Formal analysis; Investigation; writing—original draft/AC: study concept, methodology; validation; formal analysis/NLG: study concept, methodology; validation; formal analysis/AS: Study concept, methodology; validation/AR: manuscript preparation and drafting/PH: manuscript preparation and drafting/ME: study concept, validation; formal analysis; manuscript preparation and drafting/SM: study concept, validation; manuscript drafting/MZ: study concept, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript preparation and drafting. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This work was carried out by the HAS (Haute Autorité de Santé) whose aim is to design COPD-specific quality of care indicators based on French guidelines and workshops with experts (GPs, pulmonologists, expert patients, pharmacists, nutritionists, physiotherapists, physical and rehabilitation physician, professional pathologist, public health physician). According to French Law [19], this anonymous retrospective observational database study does not require approval by an ethics committee or informed signed consent from the patients.

Competing interests

MG, AC, AR, NLG, AS, ME, SM have no conflicts of interest to disclose. PH reports grants from Avad outside the submitted work. MZ reports grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Chiesi, personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from CSLBehring and personal fees from GSK outside the submitted work, grants from AVAD, grants from FRM.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Characteristics of patients with detailed Charlson components, long-term disease, and treatment prescription. Table S2. Medical follow-up after discharge. Table S3. Time to rehabilitation care uptake after index severe exacerbation of COPD.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Guecamburu, M., Coquelin, A., Rapin, A. et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation after severe exacerbation of COPD: a nationwide population study. Respir Res 24, 102 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-023-02393-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-023-02393-7